2

Aging in Latin America and the Caribbean in Global Perspective

Following a series of opening remarks, the initial substantive session of the workshop sought to provide some international perspective around the question of aging in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), and to set the stage for subsequent sessions. The session chair, David Weir, University of Michigan, remarked that aging can be thought of as relating to individuals. Everyone ages; no one can avoid it. “We can ask someone else where do you get the glasses to help you to read? What medicine do you like for your back? Where do you put your money to save for retirement?” he commented. “Population aging, however, is a little more complicated.” Countries can age or they can grow younger. Every country’s age pyramid reflects its own history of fertility, of migration, and perhaps of war or other conflict. Just as individuals age in a world of other aging individuals, Latin America is aging in a world of other regions and countries that are also aging, he said. Scientific advances in other countries offer information of value to the region and, similarly, LAC experiences can shed light on problems being faced elsewhere in the world. The advantages of comparability of joint research efforts, Weir noted, are quite great in this field.

HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE CHALLENGES WITH POPULATION AGING

Eileen Crimmins, University of Southern California, framed her remarks by saying that aging is a challenge, but in some ways, it is a triumph and a positive trend. She said that if the workshop participants had been together 50 or 60 years ago, they would have been bemoaning the very high fertility and the very young age distribution of populations. However, many countries achieved what they wanted to do, which was to reduce fertility. With reduced fertility comes an aging population. According to Crimmins, this success of the last century has provided a challenge of this century: to change institutions and understanding in such a way to adjust to the fact that populations are aging and will continue to do so.

Crimmins noted that aging is highly related to health and health care because age is related to health. It is a biological fact that everyone ages, even if they age in different ways in different places because of different environments. The change seen across the world in the last century is that not only are populations older, but also the diseases and conditions from which people suffer and die have changed markedly. Chronic conditions are now the major causes of death. Infectious conditions have been substantially reduced. Infant mortality was a major problem, but it has been substantially reduced in much of the world. Today, societies need to deal with adult mortality and with the fact of increased life expectancy at the oldest ages, she stated.

There are many new challenges in health and health care, some stemming from changes in health-related behaviors and life circumstances, Crimmins explained. Some populations have lived with the burden of both infectious and chronic disease. Societies previously did not have to confront issues of cognitive impairment because the prevalence was not as high as it is now with substantially older populations. This requires adjustments in medical care and monitoring, she noted. Health systems need to switch their approach to disease treatment, with much more emphasis on prevention of and care for chronic conditions. Long-term treatment of people who survive with disease is the more prominent part of medical care in an aging society, which is very different from what was experienced many years ago.

Crimmins then described an international network of researchers that has grown out of ongoing international studies. This is a scholarly group where cooperation is the mode, with the goal of helping everyone move their studies forward. One important focus of this group is understanding

the morbidity process in older populations. This process involves biological risk factors that may lead to disease conditions, which in turn may lead to frailty, functioning loss and disability, and ultimately to death. Researchers need to disentangle these aspects of health. “We need to be able to measure them to understand their importance,” she said, “and to better understand links from one dimension of morbidity to another.”

Crimmins presented a four-country comparison of hypertensive states to illustrate the value of using data from surveys that contain both questions asked of people and measurement of biological indicators. The data come from longitudinal studies in China, Indonesia, Japan, and the United States. She contrasted people who have no hypertension, people who have controlled hypertension (by drugs), people who have undiagnosed hypertension (i.e., who need to be treated but are not being treated), and people who have uncontrolled hypertension (even though they may know they have hypertension). In this example, the least healthy populations in terms of the prevalence of hypertension appear to be in the United States and Japan. Japan has the most undiagnosed hypertension, which she characterized as surprising given that Japan is the world’s longest-lived country. She said the United States looks relatively very good in terms of controlled hypertension, which she attributed to the U.S. health care system emphasis on diagnosis and drug prescription. There is a significant reservoir of undiagnosed hypertension in China and Indonesia, which have very low levels of medical intervention for hypertension.

She then presented data from the Mexican Family Life Study showing that in the Mexican population as a whole, the proportion with undiagnosed hypertension is very high (Beltrán-Sánchez et al., 2011). The percentage undiagnosed is above 80 at ages 20–39, then declines as people get older, presumably because that is when they might be expected to have hypertension. She showed an overall index of cardiovascular risk that suggests that Mexico has undergone a physiological revolution and now has worse cardiovascular risk than does the United States (Beltrán-Sánchez and Crimmins, 2013). She also presented information from an eight-society comparison of the prevalence of overweight and of measured high systolic blood pressure, suggesting that as societies modernize, weight gain patterns are not the same across countries. Culture influences how weight changes as countries become wealthier. Percentages overweight in Asian countries with relatively high incomes have increased but are nowhere near the levels seen in the United States and Mexico. She also noted that hypertension is highly related to past cultural practices and genetics. Hypertension does not vary

around the world with development in the same way as high cholesterol and weight.

Crimmins then discussed the value that longitudinal studies have relative to cross-sectional studies. Cross-sectional studies provide a snapshot of the prevalence of health problems, but these could have occurred at any time in someone’s life. They do not necessarily reflect current conditions. Understanding the meaning of the prevalence of a condition requires knowing changes in process; for example, heart disease prevalence can increase because the risk has increased or because people have been treated and survive longer. Researchers need longitudinal studies that have a time component to understand transitions (e.g., from biological risk to disease, from disease to death) both in individuals and in populations. Data from these studies provide the basis for future health and health care decisions. They allow the linking of many factors—childhood, current socioeconomic status, psychological, and health interventions—and permit differentiation of the role of one factor versus another. They also allow researchers and policymakers to pinpoint the geographic areas, the social groups, and the demographic groups where change is most needed and can most effectively occur. An important factor that should not be overlooked, she said, is that differences across countries can provide valuable insights into the situation in one particular country.

DATA NEEDS FOR AGING IN LATIN AMERICA

Victor Garcia, Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía in Mexico, provided additional context for the workshop by highlighting data on global aging from the United Nations. He noted that the world population aged 60 and older numbers around 895 million, accounting for 12.2 percent of the world population. In Latin America and the Caribbean, there are an estimated 71 million people aged 60 and older, representing 11.2 percent of the population. The percentage 60+ is highest in the Caribbean (13.2 percent), compared with 11.7 percent in South America and 9.6 percent in Central America.

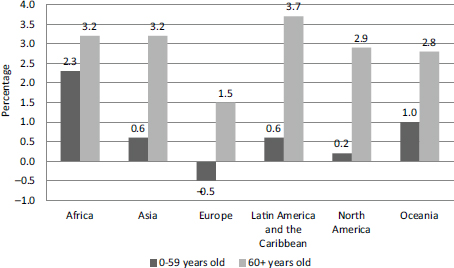

One important fact is that the world’s older population is growing much faster than the total population. The number of people over age 60 is growing at a rate of 3 percent per year while the population growth rate of people under age 60 is less than 1 percent. Figure 2-1 compares projected growth rates for 0–59 and 60-and-older populations in six world regions for the period 2015–2020. The growth rate of the older population is higher

FIGURE 2-1 Regional growth rates of the 0–59 and 60-and-older populations, 2015–2020.

SOURCE: Adapted from Garcia Vilchis (2015) based on data from United Nations (2013).

in each region, and the highest regional growth rate of the 60-and-older population is occurring in the LAC region. At these rates of growth, the 60-and-older LAC population would double in fewer than 20 years, while a doubling of the under-60 LAC population would take about 115 years.

Garcia explained that not only is life expectancy at birth increasing worldwide, but also life expectancy at age 60 is rising. In the LAC region as a whole, people who live to age 60 can expect to live another 21 years on average.

Garcia recounted that the 2002 Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing1 developed a series of goals, which he summarized as follows: (1) to empower males and females so that they reach old age with better health and well-being; (2) to enhance the inclusion and participation of older people in society; (3) to allow older people to more effectively contribute to their communities and to the development of their societies; and (4) to constantly improve the care and support provided to older people who need

_________________________

1For more information, see http://undesadspd.org/Ageing/Resources/MadridInternationalPlanofActiononAgeing.aspx [August 2015].

them. Achieving these goals, he said, requires the preparation of policies, plans, and programs. This warrants information on older populations above and beyond mere numbers of people.

Garcia then outlined some of the major data gaps confronting many countries in the LAC region with regard to older populations. While population censuses and some surveys provide good estimates of labor force participation, there is little available information about the assets of older people and their entitlement-program participation. In the health arena, there is very little information about chronic conditions from the usual health information sources, and much more and better information is needed about a variety of chronic diseases, functional capacity, depression, self-perceived health states, lifestyle habits, surgeries, out-of-pocket expenses, and the use of medications, assistive devices, and health services. He pointed to the potential usefulness of surveys of time use for information on care services that people request and receive, and to specific studies having to do with national transfer accounts, intergenerational transfers, and production and consumption throughout life.

He highlighted a manual of 110 quality-of-life indicators during old age (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe, 2006), produced as a result of recommendations from the 2002 Madrid International Plan of Action on Ageing. The indicators are grouped into five topics: demographic, economic, health and well-being, social environment, and physical environment. While this compilation is valuable in and of itself, Garcia noted that many topics are covered superficially or not at all. He cited migration and cognitive assessments as prime examples, and noted that little use is made of administrative records.

According to Garcia, the region requires special surveys on the population aged 60 and older in order to keep pace with the rapid aging of populations and to understand cause-and-effect relationships. Echoing the remarks of Crimmins, he stressed the need for longitudinal surveys that facilitate analyses of health trajectories, disability, cognition and depression, and income and consumption; as of today, such national-level surveys exist only in Brazil, Costa Rica, and Mexico. He also argued for shorter periodicity in such studies, and attention to collection of information on expectations, historical recollections, and migration histories.

James Smith of RAND talked about a particular model of an aging survey, the Health and Retirement Study (HRS),2 which has now been established in more than 30 countries. To highlight the underlying importance of this type of study, he noted that one way economists like to think about aging is in terms of support ratios. Support ratios involve the number of people in the working-age population earning income, income that can be used to support people who are over age 65. Using United Nations data, Smith showed that in Mexico, in 2000, there were 8 people aged 25–64 for every person aged 65 and older. In 2050, the ratio is projected to be 2.5 to 1. He presented similar data for other countries in the LAC region and in Asia, noting that future ratios will be extremely low across the board. One thing known, he said, is that there is nothing that can change this trend; this is future reality around the world. What countries need to do is think about how to provide assistance to older people in terms of income and health care, he stated.

Smith described the beginnings of the HRS in the United States. The study began in 1992 as a nationally representative longitudinal survey of roughly 20,000 people aged 51 and older designed to produce public use data. It was funded primarily by a government agency, the National Institute on Aging. A primary intent was to understand how individuals transition into retirement and also transition into diseases. Important features of the study include a 2-year periodicity of interviews, the incorporation of links to administrative records regarding health and pensions, and the addition of new birth cohorts over time to replenish the study population. The central motivating idea is that health, work, income, and family are all domains of people’s lives that interact with each other. People’s health cannot be understood without an understanding of their economic situation. Health will reflect their economic situation and their economic situation will affect their health. While this sounds like obvious common sense, Smith said, the fact is that most social surveys are not structured or designed to measure these varied elements and their important interactions.

Many countries around the world have recognized the value of a multidisciplinary, longitudinal HRS-type survey. Smith briefly described the

_________________________

2For more information, see http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/ [August 2015].

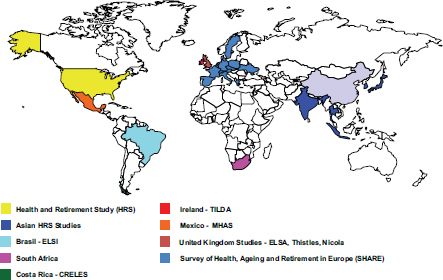

FIGURE 2-2 Countries with HRS-type studies, 2015.

SOURCE: Adapted from Smith (2015).

international expansion of such surveys, noting that Mexico was the first country to adopt (in 2002) the HRS model. The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing3 began in 2003, followed shortly by the multinational Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe4 (SHARE) project in continental Europe that now includes 19 countries. HRS-type surveys are now underway in Ireland, South Korea, Indonesia, Japan, India, China, and Brazil (see Figure 2-2). The surveys are nationally representative with sample sizes typically between 10,000 and 20,000 people, with a much larger (50,000) sample drawn in India. Cohabitating partners of survey respondents are also interviewed. The age coverage of the sample begins at age 45 in some countries, where the onset of illness may begin earlier than in Europe or the United States. Survey periodicity is 2 years.

Every country in the HRS network has committed to putting its data in the public domain, not only for the residents of that country but also for scholars around the world. Smith emphasized that this is a non-negotiable

_________________________

3For more information, see http://www.elsa-project.ac.uk/ [August 2015].

4For more information, see http://www.share-project.org/ [August 2015].

condition for being part of this network. In some countries, he observed, this is a big departure from the normal way science is done.

The aim of the network is to have comparable datasets, but the network researchers believe that no country should strictly copy the U.S. HRS. Smith explained that, in many ways, this would be bad science; for example, the ways in which economic resources are measured in China can be very different than how they are measured in the United States. Data collection in any country should reflect the policies and reality of that country. Further, there has been a good deal of scientific innovation at the country level. The English study pioneered new health measurement far beyond what the U.S. study was doing at the time, bringing biomarkers into the platform. Ireland has made important contributions to disability measurement.

Most if not all country studies are now collecting genetic samples and incorporating performance tests, he said, and links to pension and health records are common aspects of these studies. Realizing that outcomes in older age may result from experiences earlier in life, many surveys have now added a retrospective life history, not only about the important events in respondents’ lives, but also about important events that happened in the countries they were living in (e.g., for SHARE respondents, the importance of World War II).

This page intentionally left blank.