3

Health Status, Disability, and Mortality

MORTALITY TRENDS AND DIFFERENTIALS IN COSTA RICA

The initial presentation in this workshop session was by Luis Rosero-Bixby, Universidad de Costa Rica and University of California, Berkeley, who reported results from the Costa Rican Study of Longevity Healthy Aging (CRELES), which started more than 10 years ago.1 Rosero-Bixby focused on one aspect of this study, the mortality results, with other aspects of the study discussed later in the workshop (see Chapter 8 of this report).

Prior to CRELES, some estimates and analyses suggested that Costa Rica had achieved exceptional longevity, with average life expectancy at birth as high as 80 years. In international comparison, remaining life expectancy at age 90 among males was seen to be highest, and one of the highest among females. However, these estimates were not accepted by all demographers and were thought to be the result of poor data quality, Rosero-Bixby explained. One of the motivations for CRELES was to validate data from the official death registry in Costa Rica and achieve more precise estimates of mortality at older ages and very advanced ages.

CRELES started as a follow-up of a sample from the 2000 census of Costa Rica. It is a probabilistic sample comprising about 8,000 people aged 55 and older. Follow-up of this sample has continued to date, and around half of the population has died. Within the 8,000 people sampled,

_________________________

1See http://www.creles.berkeley.edu [August 2015].

researchers selected a subsample of around 3,000 individuals in order to do a nested in-depth panel study. CRELES included interviews and collection of biological specimens, venous blood, and urine, as well as physical and mental exams of participants that were done in their homes. Mortality data in this study were obtained from two sources. One source was follow-up visits in the field, and the other was computerized records from the national registry of deaths. This follow-up continued to 2014 and there were 566 reported deaths in the field and about 1,200 deaths identified as part of the death registry. A factor that facilitates this analysis is the national ID card issued to all Costa Rican residents, with a unique number that permits researchers to match the reported and registered years of birth, and to weed out or adjust inconsistencies.

The initial findings of CRELES focused on evaluation of age reporting in the 2000 census. According to Rosero-Bixby, the quality of age reporting was excellent up to age 85, after which there was the well-known phenomenon of age exaggeration (e.g., among people reporting an age of 100 years old or older, only 70 percent were in fact 100 years old or older).

The next set of findings helped determine whether there was an underreporting of deaths in the country. Of the 566 deaths recorded during the field visits, all except five cases were also found in the death registry. This was a very valuable contribution of the study showing that the death registry in Costa Rica was nearly 100 percent complete and that corresponding estimates of age-specific mortality rates were correct. Rosero-Bixby noted that the same could not be said about the thoroughness of the number of deaths that were recorded in the CRELES field visits. There was a 10 percent underreporting of deaths in the field, which is to say that deaths that were found in the registry were reported/recorded in the field as lost to follow-up. This is something to be considered in longitudinal studies and can only be detected if there is a double follow-up, both in the field visits and in the death registry.

He then presented a comparison of mortality rates by age during the period 2005–2010, comparing estimates from CRELES, the Costa Rican vital statistics system, Japan, and the United States. In terms of life expectancy, CRELES data yield a life expectancy at age 65 of 18.4 years for males, very similar to the estimate from vital statistics and to the figure for Japan, and 1 year higher than for the United States. For females, the Costa Rican and U.S. figures were in the 20.1–20.7 year range, while the estimate for Japan was considerably higher (23.6 years).

The most important results from CRELES, according to Rosero-Bixby,

were surprises. The analysis of age-adjusted mortality rates by socioeconomic status (education, wealth, region of residence) revealed that, among males, those with the least education had lower mortality. For both men and women, mortality rates were higher in the wealthier and more-developed metropolitan areas than in rural areas. The trends for wealth were not clear, and Rosero-Bixby concluded that there was an absence of economic effects.

The CRELES analysis also modeled the predictive value of a set of 20 biomarkers and concluded that biomarkers do not have much relationship with mortality. The traditional demographic indicators of age and sex explain about 44 percent of everything that is predictable or that can be explained about mortality in older adults, and the addition of biomarkers in the model increased this level to only 55 percent. The strongest predictors of mortality among older adults were performance tests, including pulmonary flow, grip strength, and timed walking distance.

Rosero-Bixby summed up by saying that longitudinal study has been useful to validating adult mortality estimates and the accuracy of the death registry in Costa Rica. CRELES has confirmed the exceptional longevity of older Costa Ricans, particularly men. It has indicated that there are no socioeconomic gradients in mortality rates, and that adding biomarkers represented a marginal contribution to understanding mortality at older ages.

TRAJECTORIES OF HEALTH FROM THE MEXICAN HEALTH AND AGING STUDY

Rebeca Wong, University of Texas Medical Branch, spoke about health trajectories from the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS).2 By way of background, she noted that discussions began in 1999 with regard to conducting a longitudinal prospective study similar to the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) in the United States. Data collection for the first round of MHAS began in 2001, with a sample of 15,100 people. This cohort was born in 1951 or earlier and was aged 50 and older at the time of the survey. Wave 2 of the survey was in 2003, by which time there had been 540 deaths among the beginning sample.

There was a pause in MHAS survey activity until 2012, when researchers went back to see the same respondents as in 2003. In 2012, the study added a new sample cohort of people born between 1952 and 1962, in order to again have representation of people aged 50 and older. This new cohort

_________________________

2For more information, see http://www.mhasweb.org/ [August 2015].

of around 6,000 people was added to those Wave 1 and 2 respondents who continued to be alive. By 2012, 2,742 previous MHAS respondents were deceased, bringing the accumulated sample mortality to approximately 3,200 people. A fourth wave of the study will commence in October 2015.

Wong explained that MHAS is a multi-theme study, very similar to the HRS, but adapted to the Mexican context. A unique characteristic of MHAS is its emphasis on migration to the United States. Data show that among men aged 50 and older living in Mexico, 14 percent were at some time migrants to the United States. She said the scientific community is very interested in studying the long-term effect of this migration.

Having three study waves allowed researchers to undertake trajectory studies, Wong said. She presented survival data for the period 2001–2012 showing that the risk of death is threefold higher for those who have both chronic and infectious conditions at the beginning of this period, compared to those who only had a chronic disease (Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al., 2015).

She pointed to a recent study (Kumar et al., 2015) that looked at the effect of obesity on the incidence of mortality and disability in Mexicans aged 50 years and older. The lowest hazard ratio of dying occurs among those with a body mass index (BMI) of 25.4, compared to higher or lower levels of BMI. Hence this level of BMI represents a protective effect, she said. Looking at hazard ratios for disability as a function of BMI, the lowest hazard ratio of having limitations in activities of daily living occurs at a BMI of 26.

Another study (Sáenz and Wong, in press) examined the risk of disability onset by education. As Wong explained, the study starts with people who had no disability in 2001, and estimates the chance that they developed a disability throughout an 11-year period. The risk of activities-of-daily-living disability onset over 11 years is three times higher for those with no education compared to those with 7 or more years of education, controlling for socioeconomic and health factors. Hence there is a very significant education gradient in the onset of disability. Based on these and other data, Wong presented information on predicted disability, by age and education, as an illustration of the value of longitudinal data for future health planning.

The discussion then turned to the importance of obesity and diabetes in Mexico. According to the Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey, in 2012 the prevalence of diabetes was 41 percent among Mexicans aged 65 and older. The proportion of this age group overweight was 40 percent, the proportion obese was 30 percent, and the proportion with abdominal obesity was 82 percent. Using data from a recent study of the

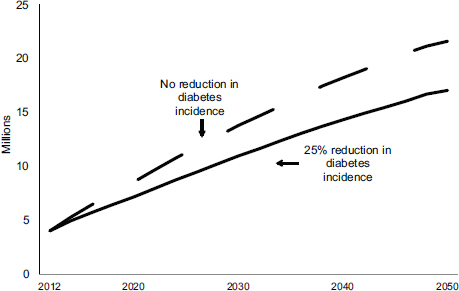

FIGURE 3-1 Projected prevalence of diabetes at ages 50 and older in the Mexican population under two incidence scenarios, 2012–2050.

SOURCE: Adapted from preliminary data presented by Wong (2015).

incidence of diabetes based on MHAS data (Palloni et al., 2015), Wong noted that the risk of diabetes increases as BMI increases. The risk of having a new case of diabetes by 2012 is 2.6 higher and 1.8 times higher for obese and overweight individuals, respectively, relative to those who had normal weight in 2001.

The usefulness of these data is illustrated in Figure 3-1, which integrates population projections with data on people’s current behavior that has been observed in the MHAS, using a microsimulation model (the Future Elderly Model) developed at RAND and the University of Southern California.3 Researchers created two scenarios, one with no reduction in diabetes incidence and one with a 25 percent reduction in diabetes incidence. Starting from an estimated prevalence of 19 percent in 2012, the scenarios suggest a rise in prevalence to 42 percent and 32 percent, respectively, by the year

_________________________

3Further information on the FEM may be found at http://roybal.healthpolicy.usc.edu/projects/fem.html [August 2015].

2050. When combined with projected population numbers, these scenarios suggest that the number of diabetics in the older (50+) population will rise from 4.0 million in 2012 to 21.6 million by 2050 in scenario 1, compared with a projected growth to 17.1 million in scenario 2, a difference of 4.6 million people. These are preliminary results from an ongoing study.

Wong concluded that the MHAS and the broader family of similar surveys have the analytical power for studies of health transitions. Policymakers and decisionmakers may use these data in order to study health and mortality transitions, and to project future needs. The availability of longitudinal data represents the engine that is moving the generation of information. Without such data, she said, researchers would not be able to pursue these lines of research. She also mentioned, in response to a participant question, that another benefit of longitudinal studies is the ability to add modules of questions to a particular survey wave, questions that investigate a specific topic such as the activities and well-being of caregivers of older adults.

HEALTH INEQUALITIES AND THE DESIGN OF THE ELSI-BRAZIL STUDY

Maria Fernandez Lima-Costa, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, focused on social inequalities in health in Brazil, and on a new longitudinal survey recently under way, the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Ageing and Wellbeing (ELSI-Brazil). She presented some background information on Brazil, the only Portuguese-speaking nation in the LAC region. She noted that national survey work in Brazil can be hampered by the size of the country and the remoteness of some areas. Older people in Brazil depend heavily on public systems for support, and 85 percent of people aged 60 and older receive either contributory or noncontributory public pensions. Seven in 10 older Brazilians use the Unified Public Health system.

In spite of improvements in social inequality over the past two decades, as measured by a declining Gini index, Brazil still has one of the highest levels of income inequality in the world. According to Lima-Costa, the magnitude of income-related disparities in health has not decreased in the last decade, despite reduced disparities in the use of health services. She presented nationally representative data for 1998 and 2008 showing that those in the poorest income quintile are more than 2.5 times more likely to report poor health than are those in the highest income quintile. Smaller but still-large differences were also seen with regard to mobility limitations and disability in activities of daily living (ADL). The key temporal point

is that the differences between the highest and lowest income quintiles did not change substantially in the 10-year period (Lima-Costa et al., 2012b).

She then presented a comparison of socioeconomic inequalities in health in older adults in Brazil and the United Kingdom, work that was based on 2008 data from the Brazilian National Household Survey and the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (Lima-Costa et al., 2012a). In general, older (aged 50+) Brazilians were less healthy, and for some conditions much less healthy, than their English counterparts. This was particularly true with regard to having limitation in two or more ADLs (36 percent in Brazil versus 23 percent in the United Kingdom). Data from these surveys were used to predict probabilities of having two or more limitations (mobility and/or ADL), by educational level and age. The probabilities rise by age for each educational category in each country, and there is a social gradient in each country such that people with lower levels of education have more disability than do those with higher levels of education. Lima-Costa noted that the probability curve for the highest-educated Brazilians was similar to that for the least-educated people in the United Kingdom and mentioned that further work is under way to determine if this is due to biological or environmental factors.

She then described a very recent study that addresses what she called the myth of racial democracy in Brazil. Brazil is a mixed country in terms of ancestry, with large representations of European, African, and Native American backgrounds. Data from the Bambui-Epigen Cohort Study of Aging4 permit the analysis of individual genomic data, which are not prone to misspecification bias due to respondent misstatement. The upshot of the findings is that people with high levels of measured African and Native American ancestry were much more likely than people of European ancestry to have low educational level, relatively low household income, and poor health.

Lima-Costa went on to describe a new national-level survey entitled the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Aging and Wellbeing.5 This effort is based on methodology used in the HRS and the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing and includes topics of interest to the Brazilian government, which is providing complete funding for the study. Included in the study are extended modules on physical functioning; formal and informal caregivers;

_________________________

4See http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-311X2011001500002 [August 2015].

5See http://elsi.cpqrr.ficruz.br [August 2015].

the use of health services and health expenditures; and elements of the social and physical environment (e.g., violence, mobility, and discrimination). The study has a nationally representative sample of approximately 10,000 Brazilians aged 50 and older in 7,500 households in 70 municipalities. There are separate individual and household questionnaires, and individuals will undergo physical tests for blood pressure, anthropometry (weight, height, and waist and hip circumferences), grip strength, walking speed, and balance. Plans are to obtain blood samples from about half the sample, for DNA banking. Baseline data collection will occur in 2015–2016, and follow-up waves are expected to occur in 2017–2018 and 2019–2020, with sample refreshment in the later round.

Carlos Cano, Universidad Javeriana in Bogota, described work that he and his colleagues have done in Colombia with regard to assessing dementia and cognitive functioning in older adults. He began by noting several kinds of changes in cognitive function associated with age (e.g., language use, executive function, and word recall) and stressed that measuring these functions in population studies is difficult because they tend to be measured with “soft” variables. It is much easier, he said, to obtain a relatively objective measure such as BMI than to measure concepts such as mild cognitive impairment or moderate versus severe dementia.

Cano presented data from a 2013 meta-analysis of data on the standardized prevalence of dementia in the 60-and-older population in different parts of the world (Prince et al., 2013). The regional prevalence estimate for Latin America, about 8.5 percent, is the highest of all regional estimates, but not very different from some other regions. A question arises, however, about the methodology underlying such estimates, he noted.

Cano then described research done as part of the Survey of Health and Wellbeing of Older Adults in Bogota.6 This was a cross-sectional survey of the population aged 60 and older undertaken in 2012 that included a cognitive functioning component with a number of standard measures and instruments such as subjective memory loss, an abbreviated Mini-Mental state examination, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCa), and the Yesavage geriatric depression scale. The instruments were adjusted to the

_________________________

6For more information, see http://www.almageriatria.info/pdf_files/mexico_2013/Experiencias%20a%20partir%20de%20la%20Encuesta%20SABE.pdf [August 2015].

context of Colombia: for example, a biographic component was included to consider the life history of people in the 25 years prior to the survey and to gauge the bias of forgetfulness. Such a component was thought to be important in the context of a country that has experienced internal conflict dating back 50 years, with related rural-to-urban migration.

This was a study of 2,000 individuals, and Cano’s analytic focus was on education. He noted that 70 percent of the Colombian population has less than 5 years of education, similar to many countries of the region. The MoCa and Mini-Mental scores showed a clear gradient by level of education that is consistent with other studies. However, the mean values of these scores were very low, 17.3 and 15.3, respectively. The cutoff point for cognitive impairment in the MoCa is between 24 and 25. At face value, the scores from the Mini-Mental exam implied that 92 percent of the sample with 5 or fewer years of education had dementia. This seemed an unlikely result, and was contrary to the researchers’ impressions of the study population.

The results led the Colombian research team to consider different approaches to assess cognitive function. One approach focused on the six items of the Mini-Mental instrument that assessed only memory. The team found that years of schooling were unrelated to the scores for this subset of items. This suggests the usefulness of a different cultural approach to measurement, and that people with low levels of education nonetheless may have a well-preserved memory, or at least the same memory function as for other education groups. Cano then described the initial stages of work, motivated in part by collaboration with Mexican researchers, that seek to develop algorithms that identify the prevalence of dementia using cutoff points by education combined with indicators of functionality (e.g., instrumental activities of daily living) and perhaps other domains of cognitive function. The goal is to identify potential intervention points that will be useful for policy development, he noted.

This page intentionally left blank.