7

Resilience and Aspects of Well-Being in Older Age

Rafael Samper-Ternent, Universidad Javeriana Colombia, highlighted a gap in the aging research paradigm related to the recovery process among older people who face a disastrous disease or adverse event. If comparable older adults are exposed to the same stressor, he queried, why do some recover while others do not? Why do some older adults with low socioeconomic status (SES) fare better after an adverse event than older adults with higher SES? For clinicians it is very clear, and for researchers it is becoming clearer, that the process of recovering is essential to the aging process, he said. However, the aging literature is rather sparse on the topics of resilience and recovery. Most information comes from models and cross-sectional studies that talk about resilience.

Samper-Ternent said in his opinion, there is no clear line between resilience and recovery in older people. Some researchers and models have attempted to include recovery as an important part of the aging process. A basic biological model focuses on the recovery side after people have a disease and receive treatment but does not go into depth as to how to measure recovery and how this affects the aging process. He mentioned other efforts that focus on successful or healthy aging (Rowe and Kahn, 1998; World Health Organization initiatives on aging and lifecourse)1 and older

_________________________

1See http://www.who.int/ageing/en/ [August 2015].

models of the disablement process (e.g., Verbrugge and Jette, 1994) that have implications and uses in the areas of rehabilitation and functionality.

In the last 5 years, he said, there has been a new emphasis on the term “resilience” and on factors that drive or hinder recovery. Samper-Ternent noted that resilience is not a new term, having been used since World War I to describe children exposed to traumatic events but who then do well at older ages, as well as older people and the psychological factors associated with good quality of life in spite of disease and adverse events. He offered a definition of resilience as “the process of negotiating, managing and adapting to significant sources of stress or trauma. Assets and resources within the individual, their life and environment facilitate this capacity for adaptation and ‘bouncing back’ in the face of adversity” (Windle, 2011). In order to operationalize resilience, he said, there must be a major risk or adversity that carries a significant threat for the development of a poor outcome, and the impact (on functionality, cognition, and/or quality of life) has to be measured. It should be the case that adverse outcomes are not experienced; there should be maintenance of normal development or functioning, such as physical or mental health, or better-than-expected development or functioning, in the face of adversity. This is often referred to as positive adaptation. And there should be measurement or observation of supportive aspects within people’s lives and environments that facilitate the capacity for adaptation to adversity.

The analysis of resilience should proceed from different angles, he explained. Geriatricians use a geriatric assessment that has four components: medical or physical; functional; mental, which has a cognitive and psychological component; and social. According to Samper-Ternent, it is clear that to study the topic of resilience requires longitudinal data. He described initial work using such data from the Health and Retirement Study (2002–2004) in the United States and the Mexican Health and Aging Study (2001–2003). The 2-year survey periodicity allowed researchers the opportunity to observe the recovery process from heart attack, falls, and widowhood. Widowhood is not strictly reversible, but this variable was included as an event that the widow/widower can recover from on the basis of psychological characteristics and a good support network. Researchers used comparable variables from the two studies to measure four domains: physical health, functional status, mental status, and social status.

Resilience was measured in terms of the change between two points in time for all four domains. He explained this involved creating scores for the four domains and undertaking a validation process. Researchers found

that people who were less resilient (lower scores for each of the domains) were more likely to die and more likely to report poorer health. They found, overall, resilience scores were higher for Americans than for Mexicans. However, analysis by domain suggested a more complex story. At baseline, older adults in the United States were in worse condition in the health domain than older adults in Mexico, older Mexicans had more functional impairments, older U.S. adults had worse social status, and mental status was the same in both populations.

This study also considered those factors that promote or help a person to be resilient, those that put people more at risk, and differences in these factors across the two countries. Samper-Ternent described several additional avenues of investigation stemming from the observation that the factors that promote resilience are different in the United States and Mexico. One might ask, he said, about the role of social structure, the size and type of the family, urban/rural residence, labor force participation, and alcohol use. He mentioned the study results have been somewhat controversial, given that there have been no such precedent studies and no clear understanding of how to measure certain topics. He suggested this work might best be seen as a proposal of how to conduct and refine further research. He concluded that resilience is a useful concept in understanding adverse events suffered by older adults in a more comprehensive way, and that research on resilience is beginning to pick up momentum (see, e.g., Stephens et al., 2015; Smith and Hollinger-Smith, 2015). Transnational studies allow for the understanding of aging pathways in different contexts, and will help change the paradigm of aging and aging research away from a focus mainly on disease, disability, and mortality and more toward the positive aspects of the aging process.

Cecilia Albala, Universidad de Chile, spoke about aspects of nutrition and aging in Chile, summarizing data obtained through a longitudinal study begun in Santiago in 1999 and through other projects. Looking first at healthy life expectancy (i.e., life expectancy without functional limitations), she showed people with higher SES have higher survival probabilities and better health conditions, especially for women. In terms of nutrition, she focused primarily on changes in body composition. It is well known, she pointed out, that aging is associated with increased chronic disease, decline of cognitive function, and decline of the immune function, but aging also

is closely related to changes in body composition. Foremost among these are the redistribution of adipose tissue, loss of muscle mass, and loss of bone mass.

Data from the 2010 National Health Survey suggest most older adults in Chile are overweight. Using the standard body mass index (BMI) categories, only about one-fourth are of normal or low weight, with 43 percent in the overweight category and 31 percent in the obese category. With regard to abdominal obesity, more than half of the older (60+) population has abdominal obesity as measured by waist circumference. At age 80 and older, the percentage remains in excess of 45 percent. In light of these numbers, and knowing that there is a redistribution of adipose tissue with age, Albala questioned why the World Health Organization cutoff points to define obesity are still used, and whether these are the optimal cutoff points. Studies have shown waist circumference is an excellent indicator of central adiposity and could be as good as the BMI index for predicting mortality in the older adult (see Donini et al., 2012). On the basis of such studies, the Chilean Ministry of Health has adopted nonstandard cutoff points to define low weight, normal weight, and obesity. She also described studies that have sought to validate and/or redefine optimal cutoff points for BMI using measures such as metabolic syndrome and waist circumference, and reported that a BMI level of 27–28 was where the major health risk started.

Albala talked next about muscle mass, citing dynamometry (the measurement of force or power) data that show that muscle strength is positively related to BMI in both men and women. Studies of mortality and dynamometry found men and women below the 25th muscle strength percentile have lower survival chances.

Sarcopenia is the generalized loss of muscle mass, with loss of quality and skeletal strength, and is associated with mobility disorders, a higher risk of falls and fractures, a decreased capability for daily activities, loss of independence, and higher mortality. Albala said few studies in Latin America can assess the prevalence of sarcopenia, due in part to a lack of agreement on how to diagnose it. A Chilean study, using a validated algorithm proposed by researchers in the European Union, demonstrated that the prevalence of sarcopenia increases with age, reaching 40 percent among those aged 80 and older, and is higher in men than in women (Lera et al., 2015). Multivariate analyses showed that older people who were overweight were relatively protected from sarcopenia, and those who were obese were even more so.

A third major problem with regard to body composition and nutrition is the loss of bone mass. Osteoporosis is a decrease of bone mass with dete

rioration of the bone micro-architecture, which produces increased fragility and susceptibility to fractures, notably hip fractures. According to Albala, osteoporosis is responsible for a large and increasing share of disease burden worldwide, and its prevention has become a priority in public health. In Chile, the average hospitalization for hip fracture is 14 days, compared with 5.6 days for all hospitalizations.

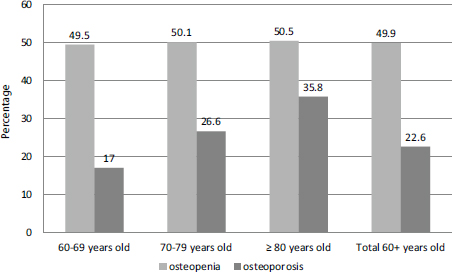

Osteoporosis is higher in women than men for biological reasons, she explained. At 80 years of age, 44 percent of Chilean women have osteoporosis compared with 15 percent of men. As seen in Figure 7-1, when data on osteoporosis and osteopenia (a lesser degree of osteoporosis) are combined, half of all older adults in Chile are affected (Albala, 2015).

Of increasing concern to health practitioners is the combination of having osteoporosis plus sarcopenia at an older age, which raises the odds of fracture by a factor of 2.2.

In conclusion, Albala reiterated that although obesity is prevalent in Chile, it is associated with relatively good muscle mass. Sarcopenia and osteoporosis are frequent conditions and very severe in terms of consequences. These conditions can be delayed or perhaps even reversed with

FIGURE 7-1 Prevalence of osteoporosis and osteopenia among older age groups in Chile, circa 2010.

SOURCE: Adapted from Albala (2015).

proper nutrition and exercise throughout the life cycle; early detection is fundamental. She stressed the value of longitudinal studies in being able to validate instruments that allow the study of a series of pathologies, syndromes, and conditions that are essential to health in older adults.

BIOMARKERS AND UNDIAGNOSED DISEASE

Soham Al-Snih, University of Texas Medical Branch, spoke about biomarkers and undiagnosed diseases. She described biomarkers as a broad category of objective indicators of medical states observed from outside an individual, measures that are accurate and reproducible. Many terms have been used to describe measurements of disease and treatment, such as biological markers, biomarkers, surrogate markers, surrogate end points, and intermediate end points. In 1998, the U.S. National Institutes of Health spearheaded an expert-group effort to unify the definition of a biomarker. The result was the definition of a biomarker as a clinical endpoint, a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacological responses to a therapeutic intervention.

Biomarkers have applications in disease detection and the monitoring of health status. They are used as diagnostic tools for the identification of patients with a disease or abnormal condition (e.g., elevated blood glucose concentration for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus) and as tools for the staging of disease (e.g., antigens or receptors to measure the extent of tumor cell proliferation and metastasis). Biomarkers can also be used as prognosis indicators of disease (e.g., anatomic measurement of tumor shrinkage of certain cancers) and to predict and monitor clinical responses to an intervention, (e.g., blood cholesterol concentration for the determination of the risk of heart disease).

Al-Snih described the characteristics of an ideal biomarker as being (1) safe and easy to measure, (2) cost efficient in terms of follow-up, (3) modifiable with treatment, and (4) consistent across gender and race/ethnic groups. The characteristics of a good biomarker when studying aging include the prediction of physiological, cognitive, and physical functions, independent of chronological age; testability without being harmful to subjects (e.g., blood tests and imaging techniques); and the capacity to work in laboratory animals as well as in humans.

The use of biomarkers has advantages and disadvantages, she said. The advantages include objective assessments, precise measurements, reliability,

and validity. Biomarker data tend to be less biased than information from questionnaires and can sometimes be used to study disease mechanisms and the homogeneity of disease risk. On the negative side, the timing of biomarker testing is critical, analysis costs can be high, and laboratory errors are a concern. It can be difficult to establish normal ranges for some biomarkers, and there are potential problems related to the storage of sample and sample longevity. There also are ethical issues surrounding the collection and use of biomarker data.

She mentioned several biomarkers of aging commonly used in laboratory investigations and epidemiologic research (for example, interleukin–6, C-reactive protein, gait speed), and noted many of the studies that have been described during the workshop have incorporated biomarker collection to varying degrees.

Al-Snih then used the example of diabetes to illustrate the use of biomarkers. She underscored the health importance of diabetes with estimates from the International Diabetes Federation (2014) suggesting that 39 million people in North America and the Caribbean are living with the disease, of whom an estimated 27.1 percent have undiagnosed diabetes. Figures for the Central and Southern America region are 25 million and 27.4 percent, respectively.

There are several markers used to diagnose diabetes, including hemoglobin A1C, plasma glucose, oral glucose tolerance, and random plasma glucose. Focusing on Mexico, Al-Snih stated the 2006 Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey found 5.2 percent of respondents with undiagnosed diabetes, based on fasting plasma glucose levels. She then described the collection of biomarkers in a subsample of people aged 50 and older in the Mexican Health and Aging Study. Using a method known as AC1 Now-NGSP certified, researchers found that the percentage of undiagnosed diabetes was 23.3 percent among respondents who had a hemoglobin A1C level above 6.5. The analysis identified two factors especially associated with lower risk of undiagnosed diabetes: physical activity and residence in a high-migration state. Higher risk was associated with both overall obesity and abdominal obesity.

This page intentionally left blank.