3

Establishing Equitable Terms for Data Sharing

Steven Tollman, director of the South African Medical Research Council’s research group devoted to rural health and head of the Health and Population Division at the School of Public Health at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, opened his keynote talk by commenting that equity and fairness issues tied to communities deserve attention, along with equity and fairness issues related to scientists.

DATA SHARING FOR GLOBAL HEALTH

Discussing the severity of health concerns in Africa, Tollman commented that the response to the complex environment that leads to adverse health outcomes requires more than one institution or research group. Collaborations around data to serve global health reflect a vision of a common world with common problems. Harnessing the most effective collaborative efforts can yield shared returns, particularly to the poorer communities and societies, he said. However, he commented, very few population health-oriented programs in the “so-called Global South” label themselves global health.

As a result, he said, there may be an underlying fear among those in the Global South. As an analogy, he said mineral and raw materials may be extracted without benefit to a community. Similarly, the Global South may be concerned that data will be exploited and extracted, or taken from a community, without a concurrent benefit to the collectors, the communities, or the data. He observed a divergence in collaborations may reinforce

this concern—researchers in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are largely data gatherers while colleagues in higher-income countries (HICs) are primarily the analysts and those who add value.

At the same time, the growing sophistication of field-based research (e.g., acceleration of biomeasures, measures of physical and cognitive function, and more sophisticated approaches to analyzing socioeconomic measures) requires expanded efforts to ensure quality. African institutions lack the needed technical capacity to extract, document, archive, and share the data as well as the methodological capacity needed to analyze complex data, putting them at a disadvantage, he said. Resolving this will require long-term investments.

In Tollman’s view, science funding represents an investment that should lead to data that can be shared to produce “new analyses, new discovery, and applications to policy and programs,” but legitimate concerns among low- and middle-income scientists, particularly African scientists, need to be considered. African scientists “may end up somewhat on the margins” and may feel that the “host communities do not benefit commensurately.” This creates “real imperatives for aware and shared leadership. It’s scientific leadership. It’s funding leadership, and forms of institutional leadership,” he said.

Tollman outlined three needs to address these concerns: (1) aware, shared leadership; (2) assessment of the “flow of benefits”; and (3) recognition of capacities required, both in the form of hardware (e.g., equipment) and software (e.g., skills and techniques).

Effective Collaboration

Tollman discussed an unusual partnership between Wits University and the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) in Africa and the University of Colorado and Brown University in the United States. In this collaboration supported by the Hewlett Foundation, the partners met annually to reconnect the partnership, which aims to take a systemic approach to promote research, training, and administration across all four institutions. Common investments from the Hewlett Foundation helped with institutional development, joint grants generation, joint research, linked capacity building, improved administration, and collaborative opportunities for students and staff.

Tollman emphasized that leadership of collaborations can take many forms, but they share several important elements:

- A start-up phase to ensure high-level commitment and lay a foundation.

- Strong, transparent, effective leadership, including possibly co-leadership by North-South partners, or African leadership where this type of leadership is a principle of the collaboration (e.g., the Human Heredity and Health Initiative).

- A clear governance structure that addresses roles and budgeting, and has an effective secretariat.

- Strong anchoring institutions.

- Explicit shared goals with active participation and a fair flow of benefits, or mutuality, involving both written agreements and interpersonal exchanges.

- Interpersonal relationships.

- Dedicated resources for collaboration.

Tollman observed that funding partners can set the terms that contribute to structure and create an enabling environment for collaboration. As he said, “If I remember one thing from anatomy, it’s that structure follows function. So it is fundamental to know what the function is, what the purpose is, and then to ensure that the structure in the enabling environment supports that.”

In response to a participant’s question about his experience with the role of supporting institutions in building effective partnerships, Tollman emphasized the vital importance of administrative support to create an “effective administrative organizational platform”; he also said funders can support and sometimes lead the leaders to develop mutually rewarding arrangements, particularly in institutions where there is the potential for leadership.

Outputs and Metrics

One incentive for data sharing is tied to outputs and metrics of research. The traditional outputs of research that academics are judged by, Tollman said, are publications and graduates. Publications are judged for quantity and quality (e.g., journal impact factor, citation index). Graduates are judged by their number, level (master’s, PhD, post-docs), and fellowships received, which are all relatively easy to measure. More complicated to measure are the emerging, less traditional metrics that result from data sharing (see Box 3-1).

As datasets are made available, a range of issues emerges, from the ability to make the datasets publicly accessible, to the demand for the data, to making some assessment of their actual use, as well as whether, how, and what is expected regarding attribution. Other metrics that he acknowledged are more difficult to measure include whether the shared

BOX 3-1

Metrics of Data Sharing

- Datasets

- Tailored/public access

- Number available

- Demand (hits and downloads)

- Actual use: Documenting second line output

- Attribution

- Secondary data use: Scientific or policy

- Policy and program impact

- Nature, extent, and “level” of impact

- Returns to study community

- Public/community engagement

SOURCE: Steven Tollman’s presentation.

data are used in science or policy, their impact, and whether the community is engaged with the work. Tollman posed the question if impact and engagement are valid metrics of achievement, and, if so, challenged the group on how to include them in systems of reward and recognition. Assessment panels, he said, are less familiar with and convinced of these metrics’ value.

Tollman argued that the cycle of recognition and reward should extend consideration of outputs that gain recognition to include those above and that they should be used to inform assessments and influence rewards, such as promotions and grants. In response to an audience question about measuring impact and how measures would be used, Tollman responded that recognition, promotion, and status should derive from impact measures that include datasets as an impact. Another participant pointed out the creation of datasets is a genuine public good, as they can be used repeatedly and never get exhausted. The impact question is important not only because of the desire to be better at explaining the benefits of sharing data, but also answering questions like, What has actually changed? How has behavior changed? How has public health improved as a result?

DATA SHARING AS AN ELEMENT OF A DATA CONTINUUM

In the discussion period that followed Tollman’s presentation, Catherine Kyobutungi, director of research at APHRC and a member of the board of trustees of the INDEPTH network, presented an analogy of data sharing to a hippopotamus. In a hippo’s natural habitat, most people only ever get the opportunity to see the animal’s eyes and the top of its head, with the rest of its body submerged in water unless conditions are right. “This is what we need to do in the context of data sharing—create the right conditions,” she said. She argued that creating the right conditions requires consideration of fundamental issues tied to data use and analysis, and broadening the discussion beyond those at the workshop and beyond Africa, to public decision makers, different cadres of people, students, lecturers, and university administrators.

Kyobutungi said she framed her comments from the perspective of an African researcher in a nongovernmental African research institution. From this perspective, she said, it is important to think of data sharing in the context of funding cycles. At the beginning of the year, her institution has “no committed funds for anything,” she said. Toward the end of the year, the focus of the board is how to continue to cover the existing staff the following year. Having conversations around data sharing is not a priority.

In addition, funding for projects versus funding for core activities is a huge issue, she said. Over the past 13 years at her institution, core support has dramatically decreased as a proportion of total funding. In 2001, core support was more than 50 percent of the annual budget. Project support increased dramatically, but without a parallel increase in core support, which is now only 7 percent of the annual budget. Thus, 95 percent of her staff costs are associated with delivering on projects and on sustaining new projects. Expectations for fundraising and project management are huge. At her institution, data sharing is a core support function, so it is considered a luxury, although people want to share data.

APHRC’s first data access and sharing policy was drafted in 2007, and the executive director led the INDEPTH data sharing and access policy process. They have a micro data portal that is part of their core funding to make 28 datasets publicly available as part of the INDEPTH Sharing and Access Repository (iSHARE) project. She said the cost is viewed as an investment and an opportunity to inform future efforts. They also view data sharing as a continuous quality improvement process. The iSHARE experience made them realize that data sharing raises issues about quality; thus, APHRC also sees data sharing as a way to improve capacity and improve data.

Returning to her hippopotamus analogy, the real hippo emerges when looking at data generated and collected in Africa, she said. Some data are lost at processing and analysis, an even smaller percentage is available for re-analysis, and a very small percentage is appropriate for sharing. To illustrate how data are lost, she cited sample sizes that are too small or losses at the re-analyze stage. “The biggest data loss is at the re-analyze stage,” she said. “Once the project is closed, it’s closed. So there are mountains of data sitting even in our own institutions.” Shared data are a miniscule portion of the data collected in Africa. “If we need a pipeline for sharing, we cannot have that pipeline if we are losing data across the continuum,” she said.

A Uniquely African Issue?

Kyobutungi posed the question of whether data sharing is a uniquely African issue and argued that to a large extent, it is. “Why is it possible for a student in the North to request data from us at APHRC or from iSHARE, but not the other way around?” she asked.

She gave two possible answers, the first having to do with the source of the data. “If I went to Harvard [and] checked the Harvard data-sharing platform . . . maybe 80 percent of it is about America. It is more likely that somebody from Harvard wants to analyze data from Kenya than somebody from Kenya wants to analyze data from America.” U.S. data are available, she said, but are unlikely to answer questions of interest to African researchers or institutions.1

The second reason has to do with greater access to data and thus deeper exploitation of databases in the Northern Hemisphere, she submitted. She pointed out that it is highly likely that a student from the South would find that an inquiry to the Harvard data-sharing platform would already be answered. The number of scholars, for example at the master student level, with access to data from the North means that the data are deeply exploited. On the other hand, the South has many unanswered questions, she said. She suggested that the Northern students could have 15 potential questions for every 3 that have been answered by African researchers. So in a way, she said, this is a uniquely African issue. “It’s not

_______________________

1A participant made the point that any large research project in the United States is required to address in the application for research funding a data-sharing plan and that there are data archives in the United States. Certain well-resourced large studies make data available themselves through study websites, and most studies, including studies that have terminated, have accessible data; for example, the University of Michigan’s ICPSR data archive. There are levels of data access, with some available through public release, some with restricted use that requires an approved data use agreement, and others that are considered sensitive and may be accessed through data enclaves.

that Africans are resistant to data sharing, but circumstances and magnitudes are different,” Kyobutungi said.

Northern institutions can be fast adopters of data sharing because they have data-sharing practices, platforms, policies, and metrics in place, she said. African institutions operate in a different resource environment. The environment for data access is not the same for APHRC, with its small amount of core support, as it is for Harvard or the London School of Hygiene, she commented.

Capacity

Kyobutungi argued that “if we had the resources, perhaps we wouldn’t be so afraid [to share data],” noting if African institutions were able to use their data more, it would not matter. She argued that capacity is needed to “generate good data, capacity to process it, [and] capacity to use it” and that sharing would then follow as a logical outcome. Building individual capacity is not enough, she said. The environment in which individuals operate has to be enabling. The conversation needs to broaden beyond workshop participants and may have to start with the basics about data quality, sharing, and the potential benefits given that data are available. Institutions need to have the right policies and the right guidelines and procedures for research contracting, citing the Council on Health Research for Development (COHRED) as an example. And, she continued, domestic funders have to be brought into the conversation since “a lot of our universities, public universities, are funded domestically.” Addressing capacity challenges, she said, is long term and must consider the skills needed and people committed to contributing to the whole cycle of data generation. Kyobutungi suggested that funders consider requiring a capacity-building plan to accompany the currently required data management plan. “If you are demanding data sharing, data sharing has to go with capacity building. . . . We need to embed capacity-building initiatives within the small grants that we are working with,” she said. Research institutions need more core support for the activities to enable data sharing.

Kyobutungi made the point that while APHRC has a small micro data portal, there could be benefit over the longer term of “regional initiatives where there is one institution that does archiving.” The regional archive could respond to requests, rather than every institution with data have an archiving and sharing function in perpetuity. She pointed to many existing African health networks as those that should be nurtured.

She urged broadening the conversation beyond the current workshop to public decision makers and other cadres of researchers. This requires looking at the whole continuum of data production—data generation,

curation, management, and analysis—and not viewing data sharing as the primary outcome of the conversation. Considering inputs at the front end will facilitate data sharing as an outcome, she concluded.

H3AFRICA CONSORTIUM: DATA SHARING, ACCESS, AND RELEASE POLICY

Michele Ramsay, director of the Sydney Brenner Institute for Molecular Bioscience and a professor in the Division of Human Genetics, the National Health Laboratory Service, and the University of Wits, spoke in her capacity as principal investigator in the Human Health and Heredity in Africa (H3Africa) Initiative.2 H3Africa started in 2010, with funding from the Wellcome Trust and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), to enhance genomic research on African populations conducted in Africa rather than relying on work done in Europe and North America. The project is a partnership focused on capacity building, with the goal of enabling data producers to also become primary data users and analysts. There are currently ten collaborative centers, seven smaller research projects, three ethics project (with an additional three pending), three biorepositories, and a pan-African bioinformatics network.

The project went through multiple phases before it was ready to share data. It did not begin with an ethics component, she said, but this is now an important part of the initiative with discussion about informed consent, broad consent, and sharing not only data but also biological samples. The project’s three biorepositories make the biological resource available for future data generation. If the resource is used to generate new data, the new data have to come back to H3Africa to share with all those involved. The pan-African bioinformatics network, called H3ABioNet, focuses on data management, storage, and analysis. H3Africa promotes fairness by ensuring that the lead institutions are based on the African continent, reflecting a commitment to build capacity. There are also collaborations with institutions in multiple countries in Africa as well as partners outside the continent.

The primary goal of the consortium is to derive the greatest possible benefit from the data generated. H3Africa operates by having a series of working groups. One group has focused on data harmonization. She reported that continued work is needed to ensure the data are equivalent for analysis. Another working group is focused on developing a policy on

_______________________

2For additional information about H3Africa, see http://h3africa.org/ [August 2015]. Also see H3Africa Consortium et al. (2014). Research capacity. Enabling the genomic revolution in Africa. Science, 344, 1346–1348, at http://www.sciencemag.org/content/344/6190/1346. long [August 2015].

data-sharing access and release and includes representation from all the H3Africa projects and input from the funders.

She said the principles developed for H3Africa data sharing include

- maximizing the availability of research data, in a timely and responsible manner;

- protecting the rights and privacy of human subjects who participated in research studies;

- recognizing the scientific contribution of researchers who generated the data;

- considering the nature and ethical aspects of proposed research while ensuring the timely release of data; and

- promoting deposition of genomic data in existing community data repositories whenever possible.

One of the largest challenges for H3Africa has been to engage with African ethics review boards since few of them are familiar with the concept of broad consent, particularly for biological samples. Ramsay noted a possible fear of sharing because of a concern about stigmatization or harm, which has prompted discussion of the benefit of sharing.

Ramsay said the nature of the data—whole genomes or genome-wide genotyping data—made H3Africa decide to leverage existing community data repositories in a format that is the same as other formats so data can be retrieved, analyzed, and compared, rather than build new repositories. They also discussed mirroring the databases on the African continent to make them more accessible to African researchers. Their data will include phenotype (e.g., demographic, health, and disease) as well as genetic data, and will enable analyses of the connections between genetic variation and phenotype.

H3Africa has developed a policy in terms of data sharing, access, and release that builds on the principles discussed earlier and that aims to strike a balance of ensuring safeguards to protect the participants and the people who generate the data, while maximizing the ability of investigators to advance their research and then promote wider research.3

H3Africa Data-Sharing Timeline

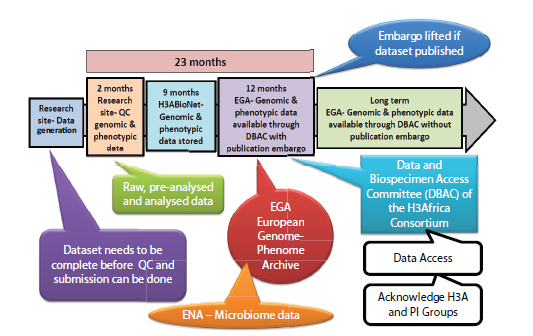

H3Africa has a data-sharing access and release policy that articulates managed access rather than full open access via a complex timeline (see Figure 3-1), Ramsay explained. It allows time for the data generators to analyze the data before the data can be widely analyzed and accessed

_______________________

3See http://h3africa.org/about/ethics-and-governance [August 2015].

FIGURE 3-1 H3 data-sharing timeline.

SOURCE: H3Africa Data Sharing, Access & Release Policy. See http://www.h3africa.org/images/DataSARWG_folders/FinalDocsDSAR/H3Africa%20Consortium%20Data%20Access%20%20Release%20Policy%20Aug%202014.pdf [August 2015].

by others. It builds on the policies and guidelines of the NIH and the Wellcome Trust in terms of sharing of data, but it has been tweaked to accommodate a sense of fairness for this project on the African continent.

Data and Biospecimen Access Committee

H3Africa is putting in place a combined Data and Biospecimen Access Committee (DBAC) so that requests for data and biospecimens are considered jointly and, according to Ramsay, will be constituted in such a way that it promotes fairness. The DBAC will represent different disciplines and include a layperson. The majority of members will be Africans. The committee will develop policies for internal and external access and will review applications to ensure compliance with what the ethics review boards originally approved and the consent given by the participants. Every project will be slightly different, Ramsay noted, and it will be a challenging process in that it will require review of the original consent and assessing the benefit to be gained from the research in each instance.

The DBAC will be doing scientific review, but they will want some evidence of previous scientific review of the proposals. Researchers who are approved to access the data will be asked to prepare a summary of their study to post online so other people can see what kinds of analyses are being done. They will also sign a data-access agreement that will delineate the research to be done.

Researchers who access the data will have to ensure that they will provide confidentiality, that they will not try to identify the individuals, that they will keep the data secure, that they will not share the data with others who were not named on the application, that there will be legal compliance, and that they will acknowledge the data generators and the bigger H3Africa Consortium project. They will also be asked to provide an annual report to the H3Africa coordinating centers.

A participant raised a question of whether secondary analyses should be required to be reviewed by ethics review boards as well, and whether this might mitigate concerns. The discussion indicated that this policy varies across universities. The DBAC for H3Africa will put caveats on the review and look for evidence of scientific grounding but require projects to go back to ethics review boards.

Long-Term Data Storage

Ramsay explained that long-term data storage will be in the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA), which mitigates the issue of needing capacity to store and analyze and release the data, because EGA will do that work. EGA safeguards include a double de-identification of samples so that it is very difficult to link them back to the origin and an encryption process, Ramsay said. Non-human data (e.g., microorganism data or microbiome data) will go into the European Nucleotide Archive.

Fairness

Ramsay pointed out the policy has not yet been tested since H3Africa is now in only the second year of a 5-year project, with the first datasets expected this year. She said that everybody recognized the added value through sharing and is comfortable now with this issue of managed access. There is a slightly longer timeline for the data generators to use the data than might normally be the case for other projects, but she said there is a willingness to share. She also pointed out that H3Africa tries to encourage people to collaborate so that they can build capacity for data analysis, rather than “just being independent users.” Ramsay said she thinks it important to analyze data in context, something that H3Africa allows.

Sustainability

A participant raised the question of sustainability since the initiative is funded outside Africa. Ramsay responded that sustainability is an important concept. The consortium is working to ensure that governments help sustain the initiative by supporting it as an important area of research. She reported the South African Department of Science and Technology is involved as a co-investigator. As part of the H3Africa Consortium, there is also an outreach program to garner wider support from governments since the project is building an incredible bioresource and data resource that really will be used for future research, she added.

Cultural Differences

A participant observed that H3Africa includes a number of African countries and asked whether this has raised harmonization or other issues given cultural and other differences. Ramsay responded with an example of DNA sharing, which, like data sharing, has a history of concern in some countries when DNA is proposed to be sent outside their borders. Resolving the DNA sharing issue has meant multiple conversations to gain an understanding of the fears and explain the benefits.

FAIR RESEARCH CONTRACTING

Jacintha Toohey, policy project adviser of COHRED, presented COHRED’s Fair Research Contracting (FRC) Initiative and how it contributes to equitable data sharing.4 According to Toohey, “COHRED contributes to the global health and development arena in a unique manner by enabling the growth of research and innovation systems in low and middle-income countries.” They believe that achieving and sustaining global health research is dependent on the capacity of LMICs to use science and innovation to solve their priority health and development problems, both on their own and in partnerships with HICs, as well as within their own arena of researchers, innovators, and institutions.

Toohey noted the Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research has called for acknowledgment that “the persistence of inequitable LMIC-HIC research partnerships be acknowledged.” In 1992, the Hesperian Foundation published the book Where There Is No Doctor: A Village Health Care Handbook aimed at putting essential health knowledge in the hands of

_______________________

4For additional information about COHRED and its work in Africa, see http://africa.cohred.org/ [August 2015].

LMICs without access to health care.5 The FRC wants to achieve a similar goal for health research contracting where there is no lawyer, she said. To do that, they have developed tools for researchers in LMICs who do not have legal capacity or frameworks to negotiate global health research partnerships.

In 2006, the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh, raised the issue of inequitable research-contracting practices with the World Health Advisory Committee on Health Research and then took up the issue of international collaboration on equitable research contracts with COHRED. In 2009, David Sack and colleagues published “Improving International Research Contracting”;6 and in 2011, a think tank was convened to identify the issues problematic in research contracting practices. In 2012, a forum was held in Cape Town to identify these issues further and discuss how to implement solutions. Experts met again at the Bellagio Centre in Italy, where the concept was established of moving toward fair contracts and contracting in research for health when there is no intellectual property lawyer.

As Toohey explained, the FRC Initiative believes that HICs are called to engage in good partnerships, which means a move toward leveling the playing field in global health research, strengthening of capacity in LMICs to engage in better partnerships, and reducing LMIC dependence on goodwill in HICs. In response, the FRC has identified best practices for research contracting and developed tools that are then placed in the hands of institutions, as well as governments, with limited legal capacity and also where there is no legislative framework.

Toohey emphasized COHRED’s view that good practice in research must result in equitable partnerships and include not just a code of conduct for researchers, but also an approach that considers the contractual and negotiation process as important as the research protocol. COHRED is currently developing the COHRED Fairness Index (CFI), which will foster accountability and transparency in research collaborations with LMICs.

The index is in an early stage of development, but one component ready for implementation is the FRC tool, which can guide discussions when entering into research collaborations and partnerships or when negotiating partnerships. She emphasized not every partner is the same in a negotiation and that striving for equity does not mean striving to

_______________________

5Werner, D., Thuman, C., and Maxwell, J. (2013). Where There Is No Doctor: A Village Health Care Handbook, Revised Edition. Berkeley, CA: Hesperian Health Guides.

6Sack, D., Brooks, V., Behan, M., Cravioto, A., Kennedy, A., Ijsselmuiden, C., and Sewankambo, N. (2009). Improving international research contracting. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87, 487–489. See http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/87/7/08-058099/en/# [August 2015].

be the same. Instead, negotiations should involve frank and transparent discussion about how partners can expect to contribute and benefit from collaborations based on each other’s capacities and resources.

The FRC identified six key issues that when properly considered by both partners can lead to substantially improved outcomes for LMICs and their institutions, according to Toohey:

- Strategies for negotiation. LMICs should never sign a contract without the opportunity to provide input into the partnership. Each partner should hear the other’s motivations, priorities, and expectations of the outcomes. Different types of partnerships will raise different types of contractual issues.

- Compensation for indirect costs. Contracts should foster and promote a full costing model.

- Capacity building and technology transfer. Partnerships should include a commitment to capacity building.

- Ownership of data and samples. Consideration should be given to how to maximize the benefits of owning the data.

- Intellectual property rights. Joint ownership, including of the research findings that come out of research collaborations, should be explored.

- Research contracts in (legislative) context. FRC is studying where there are legislative frameworks that are missing, and how they can promote fairer research contracting practices in countries with no supportive mechanisms.

Toohey stated that fairness in data sharing is a key component of fair research contracting, as well as a component of CFI. Defining fairness in contracts and then measuring it in a certification system are unresolved issues, but will be an indicator in the fairness index.

Toohey highlighted five key areas related to fairness in data sharing with which the FRC is grappling: (1) allowing sufficient time to analyze data and publish before sharing; (2) contracting to ensure fairness to LMIC partners without research or legal contracting offices; (3) contracting with the researchers instead of the institution, which may deprive the research institution of essential resources and influence; (4) insufficient provision for sharing in post-trial benefits, including related intellectual property rights that go downstream of research projects; and (5) LMICs lacking legislative frameworks to properly deal with research and research outcomes.

The goal of COHRED and FRC is to create an environment where all partners are able to negotiate fairer contracts that will enhance research and innovation for health and bring about global health benefits. Refer-

ence to data sharing or data rights in contracts should mirror the data-sharing policy that partners negotiate.

In response to a question, Toohey said the FRC has three tools available: a fair research contracting guidance booklet, a negotiating booklet, and checklists related to policy and frameworks. FRC has conducted workshops with the Swiss National Science Foundation and the London School of Medicine and is implementing the tools with researchers. The CFI is currently looking at indicators of fairness and how to measure them.

DATA PUBLICATION AND CITATION: THE PUBLISHERS’ PERSPECTIVE

Caroline Wilkinson, the open-access relationship manager at Ubiquity Press, a small open-access publisher based in the United Kingdom, gave an overview of issues around data publication and citation from a publishing perspective. She explained that Ubiquity Press “aims to return control of publishing to the research community by providing access to sustainable and affordable publication services. The company takes a comprehensive approach to publishing, viewing any of the outputs of academic research as potentially publishable.” In addition to traditional journal and book publishing, Ubiquity Press publishes data papers and is experimenting with publishing software and bio resources, any sort of object, digital or otherwise, associated with research.

Wilkinson shared her view that the focus of the open-data movement is on re-use and reproducibility, rather than just widened access, as was the case with the parallel open-access movement. Many open-access publishers, such as PLOS, are now insisting that the data underlying a paper are made openly available. In most cases, open data are deposited in a data repository. Publishers like Ubiquity are also experimenting with data journals.

According to Wilkinson, the highest-profile example of a data journal is Nature’s Scientific Data, which launched last year. Earth Systems Science Data was one of the first and GigaScience is a major big data publisher. Ubiquity Press publishes “metajournals,” which provide a publishing platform for data software bio resources. Major publishers, such as Wiley, Sage, and Hindawi, are also experimenting with data journals.

Data papers, with the data creator typically the lead author, incentivize authors to follow good practice in releasing and citing data. The paper acts as a proxy for the dataset itself, she explained. It advertises the work, encourages re-use, promotes collaboration, and provides a measure of impact. It makes citation much easier since the data paper is included in the reference list of research papers for a project and the network for

citation of papers is already in place. Citations can be tracked. Ultimately, data papers provide context and enable others to re-use the data properly.

In Ubiquity metajournals,7 data papers look very much like traditional articles but are clearly labeled to avoid confusion. The key role of a data paper is to provide context for the data. It includes information about the special and temporal coverage, data collection methods, and rationale for the collection. It also contains very detailed information about the data format, including file types, any quality control measures that were applied to the collection, and, very importantly, where to find the data in the repository and how to access them. The paper includes a very prominent section about the re-use potential for the data as the authors perceive it. Finally, there is a clear statement about how to cite the paper.

According to Wilkinson, citation is vital for data sharing to be effective. It provides a reliable means of retrieval and identification, usually by means of a digital object identifier. It promotes data assistance, and possibly most importantly, it provides a means of giving data creators recognition for their work. In her view, publishers can help to promote this by providing clear guidelines on citation. There is no single way to cite data, but good guidelines are available (e.g., http://www.force11.org [August 2015]). Ubiquity Press’s guidelines require that the citation includes information about the data creator, the data publication, the repository, the version of the data, and also its identifiers. For example,

Alexander NS, Wint W (2013) Data from: Projected population proximity indices (30km) for 2005, 2030 & 2050. Dryad Digital Repository. See http://datadryad.org/resource/doi:10.5061/dryad.12734 [August 2015].

Wilkinson shared that from a publisher’s perspective, copyediting is a step where a citation can go awry, so it is important to use this step to reinforce best practices and ensure that journal guidelines are being followed.

The publishing community is working toward having data citations in machine-readable format. Many data re-use scenarios involve very large datasets, possibly from multiple sources. The ability to query them all in tandem or recombine them is very important for data sharing in the future, and, she said, machine readability is a big part of that.

She explained two possible methods for making citations machine-readable—XML or resource description framework (RDF). A very common> publishers but designed for journal articles, so it is not optimal for data sharing. She noted initiatives are under way to improve its compatibility with data publication, for example, by introducing terms such as data title version, license type, and what JATS calls “curators,” which will be the data creators.

According to Wilkinson, RDF is arguably much better suited to data description and allows information about the relationship between the data and the resulting research. It is not currently widely adopted by

_______________________

7For one example, Open Health Data, see http://openhealthdata.metajnl.com/ [August 2015].

publishers, but there are efforts under way to improve the ease of use and wideness of adoption. Wilkinson concluded by saying there is a lot of work to do, both in terms of developing the infrastructure for good citation and engaging with researchers, but publishers are increasingly embracing data publication and providing the infrastructure and network for researchers, including through use of data papers. A participant observed that the increasing integration of data archives, data repositories, journals, and libraries is going to be a powerful force for research in the future.

In response to a question about the relative advantage of data papers over fully documenting data stored in a repository, Wilkinson commented that data papers are “quite a blunt tool” that emerged to provide a bridge because data sharing is such a new concept. Integrating data papers into the existing publication network via a type of academic article is a way to engage researchers and to overcome the problem of attribution and citation. A citation to a paper will be recognized by Web of Science or Scopus, whereas a citation directly tied to a dataset and a repository may not be. Another participant likened data papers to the profile papers now being published for cohorts, often in international journals of epidemiology. Those papers have a similar objective—helping the scientific world understand what the cohort is, so that others can use it effectively.

PLENARY DISCUSSION

Robert Terry, senior strategic and project manager with the World Health Organization, opened the general discussion by commenting that several speakers emphasized the need for support for the whole research process: that generation of quality data is needed to ensure that data are able to be shared. He also observed the call for sustainability funding and core support, the point that sharing data is a form of quality assurance, and that capacity building is needed, including possibly related to data curation and management.

A participant raised a question about the distribution of responsibility to create equitable situations. One panelist suggested that it requires a negotiation of lead institutions to make sure all are in agreement. Another

panelist argued that primary responsibilities lie with funders, who can set terms for research, and with Southern institutions that have to be their own champions, particularly as part of networks. Southern institutions, the panelist said, should diffuse information such as about policies and contracts within their networks, which will make Southern institutions more informed negotiators. Another panelist suggested moving away from a focus on “North-South,” since many of the issues discussed are relevant to “North-North” and “South-South” partnerships as well.

Another participant raised the point that more work is needed to demonstrate that data sharing represents a public good, not just something that benefits individual researchers in the form of additional publications. Panelists pointed to the need to demonstrate an impact on population health.

Several participants reinforced the value of thinking of data sharing within a research cycle, not just as data extraction in its own right. Data sharing is a beginning, not an endpoint, a participant said. Another emphasized that through capacity building in the research production process, data sharing will happen naturally.

Another participant raised the issue of sustainable funding for data-management skills. He suggested that research centers create organizational structures that require projects to commit to using common data and database structures. Rather than exporting data in collaborative projects with Northern partners, the storage and manipulation of the data and preparation of the data can be done locally in the research organizations, he said.

BREAKOUT GROUP DISCUSSION: ESTABLISHING EQUITABLE TERMS FOR DATA SHARING

The participants broke into small groups to discuss two points: (1) terms and conditions for data access to ensure an environment of equity and fairness, and (2) incentives that would motivate researchers to share data.

Terms and Conditions for Data Access to Ensure Fairness and Equity

During plenary discussion of the priorities identified by the groups, facilitated by Terry, individual participants identified several potential terms and conditions for fairness and equity in data sharing. The terms and conditions for data sharing should cover the full data cycle, including long-term data sharing from the project, several participants said. The data provider should stipulate any intended use for secondary analysis and outline procedures to ensure that the intended use is a responsible

one; they should recognize and prioritize potential beneficiaries of data sharing—the individual, the community, the organization, the population at large; they should provide a technical platform for sharing data and train on use of that platform; and memorandums of understanding across institutions should specify review procedures, roles, data platforms to be used, and the like. In addition, there should be provision for broad informed consent that recognizes the range of possible future uses to ensure fairness to participants. Finally, there should be provision for feedback to the researchers who collect the data so they have reassurance their work has been used and how it has been used.

Several participants suggested that data sharing would be enhanced if there were incentives for researchers to share data. The incentives could come in the form of (a) designation of a portion of project funding for data sharing, with amounts tailored to the level of institutional capacity with the understanding that institutions that are sharing data for the first time would need more funding to build capacity; (b) investment in development of data repositories that might include African satellite centers of the repositories that exist in the North and over time, creation of centralized resources in Africa; (c) the establishment of protocols for co-authorship by the researcher who collected the data; (d) procedures for institutional recognition of the value of data sharing; and (e) a funding system that supports the work done by data management departments and provides increased funding for a larger number of shared datasets. The terms of these incentives could be spelled out in guidelines for written agreements that specify roles and responsibilities for the researcher who collected data and those doing secondary analysis, including authorship terms and recognition of both the original researcher and the institution.

Terry closed the session by commenting that he saw that many participants agreed that there is a need for an institutional approach and funding to support that approach. He also reflected on the debate on open access to publications and how open access was once “a mountain to climb” but is now commonly accepted. While the field is at the beginning of the road with data sharing, a significant difference is support by journals. He conveyed optimism that data sharing will become the norm if the technical issues around data platforms and the need for more data managers and other capacity issues can be resolved.

This page intentionally left blank.