4

Exploring the Ethical Imperative for Data Sharing

Michael Parker, professor of bioethics and director of the Ethox Center at the University of Oxford, opened the workshop session dedicated to ethical issues in data sharing.

OVERVIEW OF ETHICAL ISSUES

Parker suggested three ways to think about ethics. First, different approaches to data sharing result in different harms and benefits. Second, what is considered right and wrong is sometimes a separate consideration from the consequences (e.g., sharing data on sexual behavior might benefit science but be considered wrong for other reasons); and professional standards of conduct, or establishing a set of professional ethics for those involved in data sharing, are needed, whether related to collecting data, managing the data in a data center, or managing the sharing of the data itself.

Reasons to Share Data

Parker suggested arguments in favor of data sharing fall into three categories: (1) better science, (2) increased and better health care, and (3) explicit ethical reasons. He highlighted the arguments of each category.

Better Science

Parker noted that discussion at the workshop pointed to data sharing generating more science in a wider range of research and promoting better science. Data sharing may result in better use of science funding, he said, which is especially important in low-income settings. When datasets are unique—that is, it would be impossible to re-create them—they offer particular scientific value, and there are good ethical arguments for trying to use them.

Better Health Care

According to Parker, the better use of data might help to better use health care resources, plan services more effectively, develop more evidence-based interventions, and ultimately lead to better care for patients. He argued that data sharing might therefore be particularly important in low-income settings with high burdens of disease.

Ethical Imperative

Improving health care and generating scientific knowledge create an ethical imperative for the sharing of data. Parker opined that sharing data, if done appropriately, can help to address health inequalities, and therefore creates an obligation to participants who have consented to use the data well and efficiently. He also pointed out ethical implications of not using data, raising the question of whether it is more problematic to use samples where the consent is a bit unclear, for example, archive samples, or using additional resources to collect new samples from new participants.

Cautions about Data Sharing

Impacts on Science and Health

Parker acknowledged concerns about being scooped by others who use their data may lead scientists to focus on short-term goals, such as publishing, and be less willing to engage in a more deliberative, strategic approach to their research, which might reap more benefits. It also might undermine scientific capacity in low-income settings, which could have important implications for the future of science. An emphasis on data sharing could provide an incentive for scientists to focus on careers that analyze data, at the expense of generating new data. He noted concerns are also expressed about potential poor-quality secondary data use and the resultant reputational risk for those who produced the data. Data shar-

ing can also lead to opportunity costs as the resources needed for curating and sharing data prevent a focus on areas of new scientific inquiry.

In addition to the scientific impacts that will ultimately affect health, poor-quality analysis of data may impact health quality.

Ethical Cautions

Parker summarized some of the ethical considerations he said he heard raised during the workshop:

- The need to manage privacy and confidentiality when data are being shared and datasets can be merged, such that the sharing may generate information that allows people to be identified.

- Concerns about “moral distance” or whether the uses of data by those a distance away from where they were collected will take into account the expectations of those who first collected and provided the data in a particular context.

- The possibility of valid consent—and if so, is it really possible to achieve valid consent when the future uses of data are unclear?

- Issues related to social justice, including stigma and discrimination.

- The potential impact on public trust and implication for future research. For example, if data are used inappropriately, such as published in ways that are discriminatory, that might have implications for the trust of communities and the public in the scientific enterprise.

- Issues related to decision making and who decides who gets access to data and who does not, and what counts as appropriate involvement in the data-sharing and data-access policy process.

Call for Empirical Research

Parker argued that ethical claims made about data sharing are claims that could and should be tested empirically. “Data sharing is a means to better science, it’s not better science in itself,” he said. Potential empirical research can range from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to qualitative research to development of models for data sharing to understanding the benefits of data sharing. Research, he said, could be conducted on questions relating to valid consent, respect, and autonomy; social justice; what it means for research collaborations to be fair; and requirements for public trust and confidence in the scientific enterprise.

For example, research could explore what models of consent work, recognizing that consent by its nature, even in high-income settings, is imperfect. Parker noted valid consent has to encompass information and

understanding, voluntariness, and competence. Achieving these three things is imperfect since the process of obtaining consent is a social phenomenon with real-world people in a complex process. Consent is inevitably less than fully informed since, for example, potential future uses of data are unknowable. Nonetheless, research could help continue to develop an evidence base for models of good practice.

A participant pointed to a substantial evidence base on privacy and confidentiality that could be better used in decision making. Another participant questioned the value of doing RCTs on data sharing since a lot of research has already demonstrated the ability of data sharing to increase knowledge. He suggested instead an understanding of the complexity of data-sharing issues, for example to differentiate between data known to be important today and those that will be important 10 years from now. He commented there is a lag issue that is a hard problem to solve for a data steward.

Data Utility

A participant pointed out tension between data that have broad versus narrow utility. Some data are going to be widely re-used almost immediately. He stated that the case for sharing those data is unequivocal. Less clear is what to share and what to preserve among things that might be very important but have a narrow utility. Another participant shared that funders are struggling with this issue. Funders have a broad policy on data sharing at this stage because it is too hard to know what to keep and what not to keep.

Social Justice

In Parker’s view, the inherent imperfection of consent calls for more attention to questions of social justice. Consent alone does not make research ethical, he stated. In addition to valid consent, responsible conduct in data sharing requires protections around discrimination, security standards, and standards of confidentiality and privacy. There should be very good governance and oversight, and the security of the data should be guaranteed, he urged.

Researchers and participants in low-income settings should be able to be confident that broad social justice considerations are also being taken seriously, in his opinion. They should be able to expect that research funders and research institutes are attempting to address global inequalities, that research is socially relevant, and that it is addressing the so-called “10:90 gap”—the view that 10 percent of worldwide resources devoted to health research are put toward health in developing countries,

where over 90 percent of all preventable deaths worldwide occur. How to best address social questions is, in his view, another empirical question.

Public Trust and Social License

Parker said that social license, a concept used in sociology, is relevant to data sharing. Sociologists argue that there is a distinction between the social license given by society to researchers and the mandate claimed by researchers. He said that it is “very important that those two things are close to each other for trust to persist in a research enterprise.”

An example in the United Kingdom is historical work in which organs from children who died were retained without the full consent of their parents. The doctors conducting research believed they had a mandate to conduct the research, but it became apparent that there was no social license for that research, and a problem arose. Similar considerations need to be thought about in the context of data sharing, Parker said. While work can be done with communities to help them see the value of data sharing, for continued sustainability, “research needs to be compatible with the reasonable expectations of the relevant stakeholders.”

Fair Trade

Fair research collaboration, or fair trade, is an important ethical consideration as “successful science depends upon sustainable scientific collaborations between researchers in low- and high-income countries,” Parker said. In interviews he has conducted with scientists in Africa and Southeast Asia, capacity building, fairness and respect, and an opportunity to set scientific agendas and operate at the cutting edge of science are high on their list of requirements for fair collaboration. He suggested an opportunity to develop an evidence base on the difference between good and bad collaborations by developing “high-quality research looking at different ways of managing data sharing.”

Data Ownership

A participant raised a question about data ownership, conveying that he views the researcher as the collector and custodian of the data, but not the owner. Parker responded that he does not favor the concept of ownership, although it offers ways to formalize protections and manage exchange of data. Instead, he would rather “focus on the things themselves that are important rather than focusing on ownership.” The issue of respect cannot be solved by declaring an owner, he said. Instead, it requires an approach to data sharing that involves setting the stage for

reasonable behaviors at the outset which, in turn, requires reasonable oversight and governance, and a fair exchange.

In response to a participant pointing out that law in certain countries requires a data owner, Parker said there might be a need to have someone accountable by law, and that could be considered ownership if necessary. He gave a UK example where “no one owns a human body when someone has died, but there are all sorts of rules about who has to do what and how it has to be treated.”

Another participant noted a shift in the United States away from ownership toward custodianship, a challenging situation especially with national surveillance systems where the states contribute data. The question is not ownership, it is custody, she said: Whoever has the data in their possession has to have responsibility and is the custodian.

In closing, Parker asserted, “We need to think holistically. If we’re serious about promoting science rather than promoting data sharing in its own right, then we need to think in a rounded way, and we need to generate evidence about what’s the best way of doing that.”

In response to questions from several participants about who needs to be involved to move forward, he suggested engagement of as many stakeholders as possible, making sure there are protections in place, and thinking carefully about the justice elements. Ethics committees have an important role to play, he said, but are often less than perfect and do not have adequate resources or training, perhaps especially related to data sharing. Consideration of ethics needs to continue beyond approval by a committee, because “many of the most interesting and challenging ethical issues arise after you’ve got the ethics approval.”

STAKEHOLDER PERSPECTIVES ON DATA SHARING IN LOW- AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES: FINDINGS OF A MULTISITE STUDY

Susan Bull, senior researcher in international health research ethics and head of Global Health Reviewers, was the first of several presenters discussing the findings of a multisite study funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Overview of the Study

According to Bull, the study involves the University of Oxford in England, and five low- and middle-income country (LMIC) sites in India, Kenya, South Africa, Thailand, and Vietnam. It is designed to look at the appropriate governance and management for data sharing given the increasing mandate from funders, journals, and other organizations and

given the range of ethics issues that arise with data sharing, particularly in LMIC settings. The aims of the study are to

- understand the perceptions, experiences, and values of key stakeholders in low-and middle-income settings who are involved in data sharing;

- identify principles for development of models of governance of good data-sharing practice that are relevant in these settings; and • develop resources to support the development of appropriate data-sharing policies and practices in research involving such countries.

The project included five qualitative studies along with a systematic scoping review of the literature. Bull agreed with previous presenters that if data sharing is done properly, it can improve science, and if not, it will hamper science. She observed that the arguments for and concerns about data sharing are two sides of the same coin, which underpins the point that “to achieve the advantages of data sharing, then we really need to look at how we address the concerns arising.”

Bull said the study focused on release of individual-level data, not aggregate data, and on studies of public health and clinical research. The majority of respondents suggested that curation would be needed of some datasets. The reasons cited for why this was necessary included the need for safeguards, bona fide access restrictions, privacy, less harmful or poor-quality research, and compliance. Researchers in the study also raised concerns about the commitments they made during consent processes. She emphasized that decisions have to be responsive to the context and the nature of the dataset.

Priorities were identified for policy and process development, she said. From the perspective of prioritization of data sharing, questions posed included: Which data should be shared? Why? What standards might be used to prioritize sharing data? What are appropriate data and metadata standards? More broadly, she said, at issue are the requirements and rewards needed for collection and curation of datasets and data sharing.

According to Bull, the empirical research that went along with the systematic review was the key element of the study and it started with the premise of “flipping points.” In this context, flipping points are defined as elements that might make sharing of data that is acceptable to the stakeholders become unacceptable and what is an appropriate response.

Presenters discussed the results of qualitative research focused on understanding the perceptions, experiences, and values of stakeholders

in the study sites, repeating themes that had been raised throughout the workshop.

South Africa

Blessing Salaigwana and Spencer Denny presented stakeholder views of key features of good/ethical data sharing within a South African context based on a multisite study where they sampled purposefully three different research organizations: two mostly involved in biomedical research, and the third mostly in social science research. Denny presented some main findings from the first paper that came out of the project. He reported a mixed level of awareness among their participants of the procedures and policies or issues related to sharing data, but a general consensus that sharing individual-level data at both the local and international level is for the greater good. According to one assistant investigator, “. . . the more that data is made available the more likely it is to lead to scientific impact.”

He said the exploration of questions tied to why to share data boiled down to three issues:

- the recipient of the data who would be conducting the secondary analysis,

- the value by participants of altruistic action that has global value, and

- the tension between benevolence and competition.

In the research cycle that they identified, data were described as the lifeblood of the participants’ (primarily researchers) work. In the cycle of the participants’ careers, data collection leads to exclusive analysis, which leads to publication, which leads to future funding. Free sharing of data does not complement this model. They shared familiar perceived disadvantages to sharing data, such as misuse and loss of recognition for local stakeholders. In addition to the perceived disadvantages of data sharing, they identified several barriers that deter the practice:

- lack of data-sharing precedence in South Africa;

- lack of incentives, with a sense that there are no returns to counter the risks of sharing;

- lack of specialized infrastructure such as data management and curation; and

- insufficient allocation of funding. The typical research grant does not allow for data management and curation activities to happen post data collection.

Among the study participants, there was a sense that the potential harm was greater, given the diminished prospects of benefits after secondary analysis and the geographical detachment between the data source and the end user. The project identified factors needed to minimize potential harms of data sharing, including respect for the interests of the research participants, accurate data management, preservation of professional integrity, and benefit sharing and capacity building.

The participants then discussed the formal ways that data re-use is regulated, including informed consent and the contractual obligations of the principal investigator to the funder. They also suggested participation of scientific review committees. The study did not involve any research ethic board members, but participants saw a potential role for these boards in resolving conflict between parties and protecting the interests of research participants.

Based on their interviews and focus groups, the researchers suggested that ways to facilitate data sharing include alignment of stakeholder interests, funder support for the required infrastructure, a culture of learning from prior examples (e.g., a resource guide), cultivation of collaborations, and ensuring that data-sharing plans and data-management budgets become a standard budget line when applying for research grants and in ethics review.

The research agenda they developed included two components. First, they see more work in terms of national policy developments and evaluation, with the view toward guiding principles in a South African context. Second, they see resource development to support the decision making on the ground by primary researchers and strengthening of community advisory boards.

Kenya

Vicki Marsh and Irene Jao, from the Kenya Medical Research Institute Wellcome Trust Research Programme, presented the findings of the study in Kilifi County, on the Kenyan coast. The study involves about 260,000 people who live in the catchment area of the hospital/research center.

The conversations drew on the participatory skills of the community engagement team and visual aids to help participants understand the concept of data sharing. After setting a basic understanding of the steps in the data-sharing process, participants were asked “What if other researchers would like to access that data?” and “What if those researchers are situated outside of Kilifi, outside of Kenya, outside of Africa?”

Jao reported that data sharing was supported overall, but with caution. Researchers were more strongly positive than community stakeholders. Many of the concerns or challenges identified echoed themes discussed at the workshop and were tied to perceived harms to the participant/

community (e.g., confidentiality, stigmatization, sensitivity of data) or burdens/harms for the researchers (e.g., need for resources for archiving/managing data, potential misuse of data, unfair competition). Sensitivity of data became a particular issue because of concerns about how the data were going to be used. Trust, which Marsh said is a prominent issue in the literature, emerged as an important issue in their discussions.

Jao highlighted three main findings: promoting researchers’ and the primary community’s interests, respecting autonomy and choice, and ensuring fair governance and accountability.

Balancing of Benefits and Burdens

Rather than the balance of benefits and burdens being thought of as protections, their project focused on promoting interests of the community and of researchers. For primary communities, promotion of interests involved re-use of data in relevant ways to similar populations and through a partnership with the Ministry of Health, which would regulate re-use. For researchers, promotion of interests involved promoting local scientific capacity building, with high value placed on doing this within scientific collaborations.

Autonomy and Consent

Prior individual awareness and agreement were seen as very important to sharing data. Many options were weighed, including sharing data secretly or looking for participants who participated in primary research to re-consent when a secondary request is made, and the broad form of consent. Broad consent became acceptable only as a compromise, not an ideal, and only if linked to fair decision making when data requests were made.

Fair Governance and Trust

Fair governance and trust were discussed in terms of developing policies adapted over time and in terms of how decisions will be made about accessing data in the future. Jao pointed out that issues of fair governance and trust are connected with those of promoting interests, autonomy, and consent. An aspect of fair governance discussed was to have national regulatory frameworks that govern international data sharing.

Community involvement was an important component of governance for their project. Jao pointed out more research is needed on how to go about it, but suggestions included creating awareness to communities

about data sharing, involving them in informed consent processes, involving them in policy development, and possibly involving them in decision making about access to data when requests are made. However, there were concerns that governance structures on their own cannot totally prevent misuse of data.

Jao summarized the lessons from the Kilifi site related to building trust for data sharing as needing to (1) ensure individual prior awareness and agreement, perhaps through broad consent; (2) develop fair governance processes, which include independent and accountable mechanisms, including accountability to communities, promoting local interests for communities and researchers and international data sharing within national frameworks; and (3) promote data sharing within scientific collaborations.

Thailand

Bull reported on the project on the Thai-Burmese border, a permeable border with an informal, vulnerable population that includes a migrant population that often has no legal right to be in Thailand. It involved interviews with senior researchers and junior research staff in Bangkok, and interviews with community advisory board members in the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit. The project did not include interviews with research participants because the ethics committees in Thailand thought the participants were too vulnerable and would be harmed by asking their views on data sharing.

In this site, although participants were generally in favor of data sharing, there was a very broad lack of experience, even among senior researchers, of sharing data outside research collaborations. Reservations were raised about potential harms to patients and communities, to researchers and research groups, and about the availability of resources required for effective data sharing. There were also concerns, similar to those raised at the workshop, about quality control and experience. The value of sharing data within research collaborations was familiar and very welcome, and a real core focus on determining how to get data quality that is appropriate for sharing along with questions about appropriate consent models.

According to Bull, there was not clear consensus in this site about broad consent or specific consent. Instead, there were questions about what appropriate models should be, and the desire for proportionate and fair governance processes that are responsive to the data being shared.

India

As Bull explained, the project in India involved the Society for Nutrition, Education, and Health Action, which works with women and children in informal settlements in Mumbai. Their research interests focus on child nutrition and infant feeding, with programs to address severely malnourished children, maternity care, domestic violence, family planning issues, and safe abortions. They collect empirical health service intervention data.

Like other sites, this study found that participants were generally in favor of data sharing, but most had very limited experience, and it was difficult to find participants with an experience outside of collaborations. The reservations expressed were related to power imbalances and previous exploitation with these populations. Research participants also said research should be responsive to the health needs of the community and were concerned about confidentiality, even more so than consent. They were concerned about good governance, confidentiality, and making research responsive to the context.

Field workers echoed these sentiments, and emphasized their responsibility for maintaining trust with the women served. They expressed concern that building relationships and collecting the data is very hard work, and secondary users could jeopardize that.

More senior researchers expressed concerns about harmful data use in terms of inappropriate secondary analyses, how to manage excess to preserve participants’ interests, and issues about ownership, control, and authorship. The primary finding was in the importance, given the unfamiliarity and the complexity of the topic, for demystification and clarification.

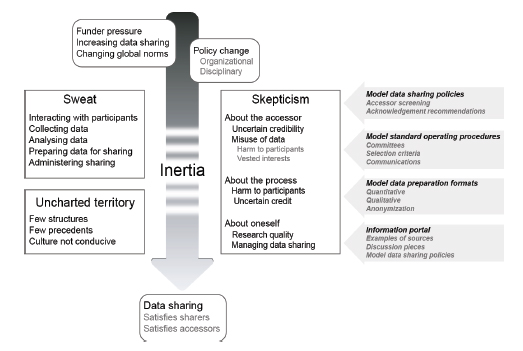

The project developed a model to illustrate funder pressures, policy changes, and the inertia tied to practical barriers (see Figure 4-1). While not necessarily an ethical component, a quite strong practical issue, according to Bull, is that collecting the data takes a huge amount of effort and there are not sufficient policies and processes to provide confidence that there is good governance of data sharing. Further, there are skepticisms and concerns about who the accessors are, what the harms might be, and what the effects for researchers of sharing data would be. These concerns lead to suggestions to develop a model data-sharing policy and standard operating procedure, provide resources for quality control, and prepare data for curation. This is more than just providing resources to inform this process.

FIGURE 4-1 Model of the data-sharing process from the SNEHA Research Study. SOURCE: Hate, K., Meherally, S., Shah More, N., Jayaraman, A., Bull, S., Parker, M., and Osrin, D. (2015). Sweat, skepticism and uncharted territory: A qualitative study of opinions on data sharing among public health researchers and research participants in Mumbai, India. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 10(3), 239–250.

Vietnam

The study in Vietnam, with the Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, was conducted in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi and also in rural areas, which gave a geographical spread. The study, Bull said, aimed to compare opinions from north and south urban and rural settings. Respondents included researchers and ethics committees, but participants had limited experience of data sharing. Data sharing was recognized as valuable in theory but not seen as a priority issue. An unusual finding for the study, not replicated across the sites, was very high explicit levels of trust in researchers and the governance mechanism.

Compared to other settings, Vietnam has a huge amount of governance about many aspects of day-to-day life, including the conduct of research, Bull explained. In Vietnam, in response to these very high levels of trust, there was an acceptance that broad consent was appropriate given the community benefit.

Researchers in turn had a strong sense of responsibility toward patients, as did ethics committees. They felt there needed to be oversight of future research data uses to preserve the interests of researchers and participants. Similar to other sites, experience with sharing data was primarily through collaborative relationships. In addition to collaborations, there was a strong emphasis on authorship being preserved in publications, including secondary analyses. This was not only to give recognition but also to ensure control of the uses, the secondary analyses, and things that are not published that will harm the population.

The project discussed draft principles for governance and policy, and what the priorities might be, which included the following:

- To ensure that the rights and interests of research participants and their community are safeguarded, including preserving privacy, the right to dignity, protection from harm, and appropriate sharing of benefits.

- To protect rights and interests of primary researchers, particularly given the potential inequalities in resources available to support local analysis and publishing.

- To be transparent and accountable.

Bull noted at this site, research participants and junior researchers were most uncomfortable being asked about their opinions. Because there is not a clear national framework and policy environment for these decisions to be made, asking someone to venture an opinion is considered disrespectful. This presents an interesting contextual issue of how to engage with some populations and, given the emphasis on stakeholder views, highlights a context in which soliciting stakeholder views can be disconcerting and perhaps even threatening in some cases.

Findings of the Five Studies

Bull reported three broad themes across all five sites, despite their differences:

- Protection of research participants’ interests, not just their privacy. While appropriate consent is needed, there is also a need to minimize stigmatization, and for some datasets, a curated process to promote benefits and minimize harm.

- Fairness and reciprocity. Participants and communities both need to see benefits of research, including research that addresses locally relevant issues and benefits health. There is also an issue of fairness for researchers and institutions in terms of building capacity, benefiting from collaborations, and getting recognition.

- Trust and trustworthiness, including ensuring scrutiny and control of secondary access to data as a mechanism of promoting trust, community engagement, and appropriate levels of stakeholder participation in decision making, ensuring that sensitive data are actively protected, and ensuring data quality.

Bull observed that information from the five sites conveyed that whether data are sensitive goes beyond what the data are (e.g., HIV status). Who uses the data and how they are used were viewed as important considerations in whether data are considered sensitive. As an illustration, she said, “particularly in informal settlements in Mumbai and on the Thai-Burmese border . . . some of the most basic data about economic status can be extremely sensitive depending on who gets their hands on it.”

Bull reiterated most data sharing in the sites was done in collaborations. For those researchers involved in collaborations, concerns about data sharing, including concerns about curation and appropriate methods, “fell away”; in fact, they suggested that data sharing is the way research should be conducted. Researchers in collaborations establish trusting relationships, have an opportunity to build capacity, and have the chance to protect participants, she said. She noted these researchers felt that research can be locally responsive and better quality; as a result of educating partners about contextually specific parts of the dataset, the research will be better. However, collaborations are very resource intensive and have the potential to substantially restrict data use, she said.

Developing Resources to Assist in Policies and Practices

Bull said the findings from the project will be published in a special issue of the Journal of Empirical Research and Health Research Ethics in July 2015. The project also expects to publish additional papers. The qualitative datasets from the study will most likely be available via the UK Data Service. The project is also developing an online toolkit available through the website for the Global Health Network.1

In addition to providing resources, the intent is to provide a site for people to contribute blogs and facilitate discussions. A free online e-learning course will cover how to think about data sharing when developing a protocol, drawing heavily on resources from other sites. The site will include policies and processes, as well as lists of data archives.

In closing, Bull called for input and suggestions from workshop participants about other available resources, as well as needed resources. She

_______________________

1See https://tghn.org/ [August 2015].

said they are trying to make resources available in a collaborative way and “not reinvent the wheel.”

Discussion

Levels of Understanding

A participant asked about the level of ignorance about data sharing in the African study and whether the researchers were developing a data-management policy. In response, it was confirmed that there is a mixed level of awareness, or ignorance, with data sharing. Senior researchers had knowledge and experience through work in collaborations. For junior researchers and community stakeholders, the study used hypothetical vignettes to depict the process of data sharing to elicit views. It was further pointed out that the institutional context had an impact on that mixed awareness, and different institutions had different perspectives. In the examples, data management emerged as a key area but not because it was being probed for. In discussion around data sharing, data preservation came up as a key area.

Community Involvement

Participatory methodologies are used to get participants engaged when they really do not understand the process. The study in Kenya drew heavily on participatory methodologies. The researchers also drew on a network of 200 representatives elected by their own communities. They now meet with the network two or three times a year. The group of people is widely representative, but has an atypical understanding of what research is. They tackled the technical aspects of the discussion by beginning with people with whom the researchers had a prior relationship. These participants had basic understanding of some of the topics, even if not about data sharing, but at least about research and what research is for. Likewise, during the focus group discussions, the researchers tried to get from the participants their views about how to involve communities in data-sharing issues.

Trust in Vietnam

A participant asked whether the strong sense of trust of participants in Vietnam reflected a power imbalance in the society. It was noted that Vietnam is a strongly hierarchical society, and that the trust placed in researchers was very strongly felt as a responsibility by researchers.

Thus, trust was conveyed in a very positive way, and there was a feeling that the right thing will be done.

Re-Consenting

A participant asked whether the issue of re-consenting was raised in the sites, suggesting that re-consent is necessary as new tools and connections with datasets are made. Although generalizations are difficult based on the relatively small study size, the researchers got a sense that people would prefer re-consenting if they thought it were feasible. However, other people felt that it was overly burdensome. The idea of broad consent was distinctly a compromise rather than an ideal.

Similar to concerns about re-consenting are concerns about finding the same people. Other sensitivities include returning to a location where the participant died. Because of these challenges, broad consent became a compromise.

Dialogue on Data

A participant commented that the discussion reflected a UK qualitative study called Dialogue on Data, which looked at the public acceptability of using and sharing administrative data. One of the findings of this study was that it is difficult to get across why people were being asked these questions, because the reaction often was “surely you should just be doing this, just get on with it.” It was quite apparent that there was a high degree of trust in researchers to conduct this kind of research, which puts researchers, the participant said, in a very privileged position. One finding that came from this research was a distinction made in people’s minds between researchers doing research in the public interest or having public benefit in an institutional setting, universities, and research institutes versus research done by commercial organizations where there would be profit gained from the data that people contribute.

Commercial Gain

A participant posed a question of whether it mattered if the research were viewed for commercial gain, an important aspect of public health research. In Vietnam, commercialization was explicitly welcomed because it was seen as the best likelihood to advance health. In three other sites, commercialization was considered to make data use extremely sensitive. Another panelist responded it may depend to a large extent on building understanding of what is at stake.

Concerns about Sharing Across Borders

A participant asked whether trust concerns were different based on with whom the data were going to be shared (e.g., within the university or with another country). In the discussion, it was noted that sharing across borders is complex. There may be explicit trust in an external organization like the World Health Organization, but local use of the data may be more likely to promote uses that are sensitive in addressing local research issues. Another participant shared an example of a PhD student from Ghana who interviewed people in different African countries about export of blood samples. The premise of the project was that people would be worried about the samples going to the North, but the researcher found they worried more about the samples going to other institutions in their own country or to other African countries. A presenter said the junior researchers and community stakeholders were not necessarily against exportation of data but wanted to know how the local community would gain from the data export.

Continuation of Data Sharing

A participant asked whether there was a sense in the communities studied that data sharing should be stopped until concerns were addressed. The presenters replied that one of the overarching findings was that data were not being shared outside collaborations and that there was widespread unfamiliarity with the topic. They emphasized a consultation process designed to explore a range of perspectives, not to achieve consensus. One presenter reported that in follow-up interviews with a few participants, those most stringent in their views about conditions for sharing tended to soften by the time of the follow-up—perhaps, he posited, because it was initially a novel concept and their views changed after talking with others about it. One person further stated that there was a “sense that we need to build stronger and more responsive policies” and “need to do more research.” Another presenter commented that participants with data-sharing policies in place tended to identify issues to be resolved, but not state them in a way that suggested data should not be shared.

PROMOTING BEST PRACTICES IN ETHICAL DATA SHARING

Participants broke into small groups to discuss best practices in ethical data sharing in six areas: (1) capacity building, (2) policies and processes for ethical data sharing, (3) action by funders, (4) actions by researchers, (5) further research and evaluation, and (6) trust and confidence.

Reports from the discussions were presented in a plenary session. While there was commonality across the groups in ideas raised, the ideas were not prioritized or synthesized, nor were the implications of strategies for implementing discussed. The ideas posed by the groups are listed below.

Capacity Building

Breakout group participants suggested the following ideas related to best practices in capacity building:

- Include data sharing as part of the research cycle itself; that is, embed data sharing from proposal development through other stages of research.

- Establish data-sharing centers of excellence. One group discussed enhancing and linking networks of research organizations.

- Utilize existing expertise of centers by requiring stronger centers to be supportive of weaker ones.

- Provide training in ethical data sharing, both on-the-job training and formal training, that would start with development of a body of knowledge informed by empirical data.

- Explore how international bodies, such as the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, can be leveraged to develop good standards of practice.

- Establish more institutional review boards or ethical review boards and more training for those boards on how to understand and evaluate data-sharing plans and the implications of data sharing.

- Improve the capacity for data management to enable data sharing on the ground, in research projects, and in research institutions.

- Build capacity for research support as well as research analysis—while the assumption is that institutions in the South need to build analytic capacity, increased capacity is also needed in areas, such as data curation, administration, accounting, IT support, documentation support, and other research support services.

- Build capacity to understand the processes that make data sharable, including documentation, what makes for quality data, standardization, and, possibly, harmonization. Junior researchers, who are the ones who tend to interface with research participants, may be a particular target. Communities and research participants themselves are an additional audience for capacity building around ethics of data sharing.

- Develop information on the costs associated with data sharing.

Trust and Confidence

Breakout group participants suggested the following ideas related to best practices in developing trust and confidence:

- Use community consultation as a way of defining and obtaining a “social license” to use data.

- Develop specific data governance mechanisms.

- Define the key stakeholders whose trust and confidence needs to be built.

- Develop pilot projects for data sharing to establish a framework and build trust.

- Develop policies in data sharing within institutions to build the trust and confidence among the partners.

- Define the ethical challenges or ethical issues related to building trust and confidence, such as transparency.

- Provide information to research participants on the issue of data sharing and ensure transparency about how decisions are made about sharing.

- Make building trust and confidence standard good practice for researchers, perhaps even considered responsible conduct of research.

- Define research as equal to data collection, data analysis, and data sharing; that is, as a fundamental component of research, not an exception.

- Approach communities with an expectation of data sharing, but work with them to develop data-sharing plans by informing the community about who the data are going to be shared with, why, and what will be learned from it, and based on their response, learn, adapt, and continue to move forward on the plan.

- Share data as a way to build trust in the data.

- Consider trust as an issue that involves everyone from funders to researchers to the communities themselves.

- Recognize historical issues that may make trust difficult for some researchers, including the post-colonial approaches to research with a North-South divide.

Further Research and Evaluation

Breakout group participants suggested the following ideas related to further research and evaluation:

- Do a meta-review of data-sharing policies to generate a standard set of templates for ways that people could organize data-sharing policies in various settings.

- Create an evaluation process to evaluate that template and its implementation.

- Conduct research on informed consent about data sharing, especially in settings where research participants have relatively low levels of education, in order to understand really how people understand data sharing on the ground.

- Conduct further research and evaluation on how to establish trust and confidence.

- Approach data sharing as an empirical enterprise, including on issues such as time to release data.

Policies and Processes for Ethical Data Sharing

Breakout group participants suggested the following ideas related to policies and practices:

- As part of the engagement and consent process, consider how much information needs to be provided; for example, how much information is needed if requesting broad consent.

- Develop policies on what and how often to provide feedback to communities from which the research data came, with the goal of frequent feedback to support engagement.

- Create governance committees that include principal investigators to address use and re-use of data in order to preserve trust, taking into consideration the role of research participants.

- Create data-management and data-analysis plans with clear protocols to address fears of sharing data given uncertainty about how they will be used.

Funders

Breakout group participants suggested the following ideas related to funders and ethical data sharing:

- Agree on what, when, how, and for what purpose the data should be made available and funded.

- Check for noncompliance based on the established data-sharing agreement.

- If noncompliant with the data-sharing agreement, take necessary steps to ensure compliance, recognizing that enforcement is difficult given resource and knowledge constraints.

- Consider developing a code of conduct for funders that would define meaningful sharing in order to avoid token data sharing and facilitate provision of usable data for research elsewhere.

- Consider how to create and enable an environment for data sharing.

Researchers

Breakout group participants suggested the following ideas related to researchers and ethical data sharing:

- Engage communities at the start of research when proposals are first being written and ensure transparency throughout, including about what and why the research is being planned.

- Research institutions need to affirmatively state their commitment to data sharing, similar to what funders have done. Ideally, there would be a statement that different institutions would get credit for if they agreed to it as the policy of their institution.

- Increase awareness of the kind of processes needed to ensure no possibility of reverse identification in legacy data.

- Create a norm of data sharing among researchers, and a system that values analysis of shared data similar to primary collection and analysis in order to attract junior researchers.

Summary Comments

The panelists closed the session by highlighting points that stood out for them in the discussion. Katherine Littler of the Wellcome Trust highlighted three areas: (1) the need for centers of excellence; (2) transparency in terms of consent, processes, and decision making; and (3) the potential to connect timelines to capacity building, as illustrated by H3Africa. Michael Parker said data sharing needs to be thought of as a cycle, rather than a one-off exercise, and that models will “need to be thought about, evaluated, and developed over time.” He pointed out that sharing will raise issues for consistency when studies involve multiple countries or locations. He also suggested development of a code of conduct or professional guidelines for researchers similar to the code of conduct for doctors that would say “something about not only the kind of things you should do but what kind of person you should be.” Bull noted most of the breakout groups focused on trust and confidence, and capacity building for institutional review boards and research ethics committees was a new and recurrent theme with practical implications. She also noted community engagement was consistently mentioned as a needed component of developing trust and confidence and of capacity building, as well as an area where policies and processes are needed.