David Carr, policy adviser at the Wellcome Trust and chair of the National Research Council (NRC) Steering Committee for a Workshop on Strengthening Science to Inform Public Policy, opened the workshop. He highlighted the interests of funders of public health research and of the Public Health Research Data Forum (PHRDF),1 which he manages, in sharing research data to improve public health. The PHRDF members, most of whom now require data sharing as a condition of funding, believe that making research data available to researchers beyond those who originally collected the data will lead to faster progress in improving health, better value for the invested resources, and higher-quality science overall, he explained.

Despite general agreement that sharing of data has the potential to generate both research and policy benefits, putting that agreement into practice is not a simple matter, Carr observed. Standard considerations such as privacy and confidentiality are of concern in all data-sharing

_______________________

1Members of the PHRDF include the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (U.S.), Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Economic and Social Research Council (UK), Human Research Council of New Zealand, Health Resources and Services Administration (U.S.), Hewlett Foundation, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (France), Medical Research Council (UK), National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), National Institutes of Health (U.S.), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (U.S.), U.S. Agency for International Development, Wellcome Trust, and World Bank.

arrangements, he noted, but particular challenges exist when data are collected by researchers in low- and middle-income countries and shared with researchers in better-resourced research centers who enjoy the benefit of analyzing the data. These issues served as the basis for much of the discussion at the workshop.

Carr highlighted the interests of the PHRDF members in having data shared in a manner that is responsive to three principles:

- Equitable. Data sharing should recognize and balance the needs of different communities involved, including those who generate the data, the communities from which the data came, secondary users of the data, and funders of the data collection effort.

- Ethical. Data sharing should protect the privacy of individuals and the dignity of affected communities, while also ensuring the maximum benefit to public health through use of shared data.

- Efficient. Data sharing should improve the quality and value of research, aim to improve public health, build on existing best practice, and avoid unnecessary duplication and competition.

Carr highlighted several initiatives being undertaken by PHRDF2 to advance the goals of increased data sharing and improved public health. He also noted several trends that point to the importance of data sharing. For example, the UK Royal Society produced a report in 2012, Science as an Open Enterprise,3 which pointed to the benefits. Funders have been supporting this value through policies mandating data sharing. Journals have also been increasingly vocal: For example, PLOS recently established a policy that requires that data underlying published research be shared. The 2013 statement by the G8 Science Ministers similarly explicitly highlighted the importance of access to both research data and research publications.4

Carr pointed to parallel developments tied to privacy and confidentiality protections. For example, the European Data Protection Regulations call for more stringent protections that could impede data sharing, and South Africa has passed a privacy law tied to human subject research. At the same time, in his view, there is growing interest in sharing clinical trial data, concerns about research reproducibility, attention to issues of dupli-

_______________________

2For a description of the initiatives, see http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/About-us/Policy/Spotlight-issues/Data-sharing/Public-health-and-epidemiology/WTDV030689.htm [August 2015].

3See https://royalsociety.org/policy/projects/science-public-enterprise/Report/ [August 2015].

4See https://www.gov.uk/government/news/g8-science-ministers-statement [August 2015].

BOX 2-1

Statement of Work

An ad hoc committee, established under the auspices of the National Research Council’s Standing Committee on Population and working in coordination with the Wellcome Trust, will organize an international conference in Africa on the benefits of and barriers to sharing research data in order to improve public health. The conference will involve the participation of representatives of national science academies in Africa as well as experts in using and generating public health data and will feature presentations and discussions on the benefits of and barriers to sharing research data within the African context. The conference will be held in a host location in Africa. The conference will afford an opportunity to raise the profile of this issue within Africa, enable the Wellcome Trust and its international partners to highlight findings of previous sponsored research on this topic, identify issues that mitigate against public health data sharing and pathways through research and policy venues to foster increased sharing, and, in general, serve as a way to bring more African voices and perspectives into the dialogue. The immediate product of the conference will be a rapporteur-authored summary that can help to inform the future course of public health data sharing in Africa.

cation and waste, and corresponding interest in maximizing efficiency. He said these concerns form the background for a discussion of data sharing.

Carr closed his comments by laying out the primary goal for the workshop—to articulate opportunities and challenges in relation to increasing the availability of health research data in the African context. The workshop built on relationships between the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and African Academies of Science. While data sharing poses issues that are not unique to Africa, a discussion within the African context was viewed as potentially valuable. The formal statement of work for the workshop can be found in Box 2-1.

BENEFITS AND CHALLENGES OF DATA SHARING IN THE AFRICAN CONTEXT: THE INDEPTH NETWORK

Kobus Herbst, deputy director of the Africa Center for Health and Population Studies, presented on the multiyear experience of the INDEPTH network,5 a network of approximately 50 research centers that run health and demographic surveillance systems (HDSS), mostly in Africa but also in India, Southeast Asia, and Oceania. Demographic surveillance involves

_______________________

5For additional information, see http://www.indepth-network.org [August 2015].

collecting information on a census of individuals in a geographically defined area, and then tracking information about them over time. It includes individuals born to residents within the cohort area as well as those who immigrate to the area; individuals are excluded when they move out of the area or die. Information is collected on measures such as characteristics of the environment of households and information about the individuals such as socioeconomic status, vaccines, HIV, nutrition, and the like. Interventions, randomized trials, and other health system interventions are conducted on the cohort populations and the outcomes of the interventions are evaluated using the surveillance data, as well as information available on disease episodes and hospital admissions through linkages with local health information. HDSS networks typically are in places with no vital statistics and represent the only information available on health status and processes in their communities.

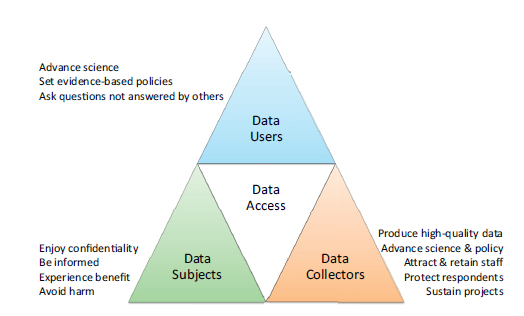

Herbst described his early thinking on data access as being oriented toward the goal to balance three perspectives: data subjects, data collectors or producers, and data users (see Figure 2-1). Data subjects are concerned about confidentiality, how the data will or may be used, and how they might benefit, or at least not be harmed. Data collectors or producers want to produce high-quality data, attract and retain staff, protect respondents, and sustain their projects. Data users aim to advance science, answer new questions, and inform policies.

Over time, he said, the network grappled with questions about where data sharing is a good thing. For example, he questioned the quality of certain data and the capacity to manage the sharing process if it extended beyond the immediate network of collaborating scientists. Questions were also raised about what data to share and the mechanics of sharing the data at the network level, keeping in mind that data must be sufficiently robust to enable sharing. Finally, he said, the network had a sense that they “should not just blindly share data”; rather, they should promote a specific research agenda and the concept of “fair trade.”

In 2008, an article in PLOS Medicine6 highlighted the debate, Herbst pointed out. One side argued that suboptimal access to data impedes international research and the potential substantial benefits of sharing, while the other side argued major technical obstacles should be addressed. The paper also pointed to the pioneering work being done by the networks and the fact that “the developing country scientist wants to move away from being primary producers of data for developed country scientists

_______________________

6Chandramohan, D., Shibuya, K., Setel, P., Cairncross, S., Lopez, A., Murray, C., Zaba, B., Snow, R., and Binka, F. (2008). Should data from demographic surveillance systems be made more widely available to researchers? PLOS Medicine, 5(2), E57. See http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.0050057 [August 2015].

FIGURE 2-1 Three perspectives on data access.

SOURCE: Adapted from Herbst, K. (2002). Wider accessibility to longitudinal datasets: A framework for discussion. In National Research Council, Leveraging Longitudinal Data in Developing Countries: Report of a Workshop (p. 43). Workshop on Leveraging Longitudinal Data in Developing Countries Committee, Committee on Population. V. L. Durrant and J. Menken, Eds. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

to analyze. They do not wish to remain hewers of data and drawers of protocols. There’s an urgent need to enable scientists in the South to play an equal role in the analysis of data they gather to support the national governments in the science policy interface and to develop science careers through appropriate citation in internationally peer-reviewed journals.”

This introduction of the concept of “fair trade” in data sharing has continued. Osman Sankoh, executive director of INDEPTH, and Carel Ijsselmuiden, director of the Council on Health Research for Development South Africa, published an opinion, Sharing Research Data to Improve Public Health, A Perspective from the Global South in The Lancet,7 which stated that fair trade in data “implies achieving a balance between the rights and responsibilities of those who generate data and those who analyze and publish results using those data. Such a balance lies in ensur-

_______________________

7Sankoh, O., and Ijsselmuiden, C. (2011). Sharing research data to improve public health: A perspective from the Global South. The Lancet, 378(9789), 401–402, 430. See http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(11)61211-7/fulltext?rss=yes [August 2015].

ing that the means and capacity to share and actively participate in the analysis of those data are in the hands of those who generate the data and not only in those who want to” (p. 401).

In 2007, three INDEPTH sites published their data in a self-developed repository. In 2008, three additional African sites joined, and the repository was later expanded to include sites in Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Nairobi, Kenya. To responsibly enable sharing of these data, INDEPTH developed a data access and sharing policy agreed to and owned by all INDEPTH members. The policy was published in the International Journal of Epidemiology in April 2011, together with the first specification of a standard micro dataset that the network would share.8

In July 2013, they launched the INDEPTH Data Repository and an indicator site called INDEPTH Stats. Since then, about 30 sites have extracted quality-assured data; twelve of those datasets are in the data repository and the rest of them are being curated for placement in the repository. PLOS ONE now recognizes the INDEPTH Data Repository as an acceptable repository for its publications.

Challenges

Herbst shared some challenges that INDEPTH encountered during the process:

- Data harmonization. Because sites had different levels of information technology available, different databases, and different data structures, there was significant work done to harmonize data and make available to sites a consistent environment within which data could be extracted and documented.

- Research data management skills. Most sites struggle with limited research data management skills. It is hard to hire and retain staff with the needed skills.

- Data quality. Maintaining data quality over many years of longitudinal individual-level surveillance is a challenge, particularly when dealing with highly mobile populations where there are no unique individual identifiers.

- Conceptual differences. Involvement of different countries introduces potential differences in basic concepts, such as the definition of a household or the unit of representation of social groups. Publishing shared data on a household dynamic analysis requires

_______________________

8Sankoh, O., and Byass, P. (2012). The INDEPTH network: Filling vital gaps in global epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology, 41(3), 579–588. See http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/content/41/3/579.full [August 2015].

-

a common definition. Similarly, it requires agreement on defini tions of educational attainment, socioeconomic status, and the like. Developing definitions requires the involvement of scientists who are working with the data, familiar with the context for the data, and have a stake in how the data are used.

- Identification of disclosure risk. Data have to be published in a way that avoids disclosure of personal identity. To illustrate the point, he shared a plausible example (see Box 2-2) of what might have occurred with a dataset on mortality data. To protect against disclosure, INDEPTH anonymizes the data in their history data. The micro data for the cause of death are also anonymized but using a different set of random identifiers so that the data cannot be routinely linked. An identity map is available for restricted access to the data when researchers with a legitimate reason and with institutional support or backing have a justification for why they need to be able to link the data. The data are still anonymized but are linkable through this identity map.

- Value proposition. A significant challenge is to make a value proposition to the 50 sites as to why they should “put a lot of effort and valuable time into supporting this process within INDEPTH,” Herbst said. While the initiatives by the PHRDF have helped make a case, he said sufficient recognition is lacking for the intellectual contribution in making the research data available. He posed the question of how to address this given the struggles faced by overburdened data managers, scientists, and leaders of research facilities within Africa.

BOX 2-2

An Example of Disclosure Risk

Kobus Herbst used the following scenario to illustrate how data can disclose personal identity:

A first-year computer science student at the University of Zululand is from one of the homesteads within the Africa Center’s demographic surveillance site. He knows about the Africa Center and the INDEPTH Data Repository. He self-registers on the INDEPTH Data Repository, and then downloads the Africa Center’s data in the repository including the individual-level mortality data with date of birth and date of death. He remembers a friend who died and wonders if he can find her cause of death from this dataset. He knows approximately her date of birth and almost exactly the date she died since it was a major event in his community. It turns out by cross-tabulating month of birth and month of death, some 93 percent of the cells would have fewer than three individuals in them. So it was a simple matter to find the record with the cause of death of this person.

Herbst highlighted solutions INDEPTH developed for dealing with the challenges and for creating capacity. He suggested theme-based joint data analysis workshops are an efficient way to harmonize data and to generate multicenter and center-specific publications with quality-assured and documented datasets. When a special issue of a journal is published—for example, a recent Global Health Action with approximately 21 publications—the dataset is also published in the INDEPTH repository.

He pointed to the master’s degree in research data management at the University of Witwatersrand as an example of beginning to build careers in research data management. To help address technical capacity, INDEPTH developed a “Centre in a Box,” a portable information appliance with a standard open-source environment for any database. The iSHARE (INDEPTH SHaring and Access Repository) project9 has a help desk to which sites can call for support. It can also be used at data analysis workshops to collaborate with other centers in a controlled environment to access and document data.

Finally, INDEPTH’s data curation workshops train managers at participating centers to use the Centre in a Box and the associated toolset. Each participating center receives a fully configured Centre in a Box and data extracted from center databases in a common intermediate form; there are common and standard procedures to process the data further and calculate quality metrics and then document the data using Data Documentation Initiative metadata.

Discussion

The plenary discussion in this session touched on several of the issues raised by Herbst and Carr, including opportunities for cost sharing, the notion of fair trade, data ownership, and ethics.

Cost of Data

It was suggested by a participant that cost sharing would advance development of HDSS data. However, Herbst expressed doubt that a scheme for charging for data and using those funds for longitudinal data collection efforts would be sustainable in the era of open access. Cost sharing, however, gains visibility for a project/site and thus attracts more funding to sustain the longitudinal data center, he said. There is also

_______________________

9INDEPTH established the iSHARE repository to share its data widely and freely on the Internet. The repository has data from three Asian member centers (APHRC–India; Kanchanaburi, Thailand; and Wosera, Papua, New Guinea) and three African member centers (Agincourt, South Africa; Dikgale, South Africa; and Magu, Tanzania).

benefit from having the data used in the North because the findings and questions contained in the analysis help to develop good proposals and receive additional funding.

The cost of collecting and maintaining HDSS data is a concern, particularly when there is limited capacity to analyze the data to influence local policy and demonstrate its value. Funding constraints have further reduced the frequency of data surveillance at some HDSS sites. The goal, a participant suggested, should remain to develop the capacity for African researchers to identify the questions that are relevant to health in Africa, along with the capacity to answer those questions using African data.

Fair Trade

A participant commented that while the discussion should not be about buying and selling data, there should be a “trade” that recognizes the currency that the North and the South have to offer. Another participant suggested the overcapacity of analytic abilities in the North should be used to build capacity in the South. While there is a polarization in skills on data analysis between the North and the South, another participant cautioned against a lens that assumes analysis occurs only in the North.

Another participant pointed to a problem in the context of intellectual property.

A key issue is data ownership. Intellectual ownership of the data implies the ability to be recognized for collecting, preparing, and sharing those data. Fairness calls for the “foot soldier” who collects the data to get credit for the work, one participant stated.

Ethical Imperative

A participant questioned the articulation of the ethical imperative as focused only on the research participant and the potential harm of secondary analysis. He referred to lessons from systematic review methodology where primary researchers wonder if their research is being used, and if so, in a proper, relevant, and pertinent way. If there were a standard on how to conduct secondary analysis, such as having a protocol submitted to peer review, secondary use would provide answers to new questions, the participant said.

iSHARE

A participant asked about the discrepancy between the number of INDEPTH sites (n = 50) and the number that have data on the iSHARE

Data Curation and Management

A participant urged more training at the bachelor’s or honors levels, as well as fellowships and other forms of support for candidates interested in data curation. There are also opportunities to share expertise across centers or partners with varying levels of expertise, the participant observed.

Data Analysis Capacity

A participant conveyed a concern about ensuring adequate salaries for dedicated staff to conduct data analysis in African centers. There is sometimes little time after finishing data collection for a project and publishing a report to conduct additional analyses, since the focus shifts to looking for additional research projects. It was pointed out that the data management plans emphasized in funder statements provide a great opportunity, as they represent a commitment by funders to provide resources to manage the data resource after release of the initial reports.

Community Engagement

In response to a question about lessons from INDEPTH around community expectations, knowledge and understanding, and benefit sharing, Herbst described several initiatives, including cooperatives that involve data subjects and an experiment at the Africa Center around “data everywhere,” in which one of the components is an interactive environment where community members can explore the data available on the community itself. Herbst commented that it should be expected that communities will have access to their data, which should be considered in planning.

Other Types of Data

According to a participant, sharing longitudinal data as collected by INDEPTH may be easier than some other types of data since the sites collect the data in the same way. Herbst commented that there are limits to which data can be harmonized, and that involvement of scientists with local knowledge and insight into the data is key to harmonization.

Data on Sensitive Issues

Some data that are collected are particularly sensitive, such as data on sexual behaviors and violence exposure, a participant said. People often agree to provide sensitive data because they trust the researcher and trust the researcher is not going to use the data in a way that would be harmful toward them. However, there is a concern that the trust may not carry over when the data are shared. The challenge is to preserve the original consent when the data are shared. Carr agreed that preserving consent is very much at the heart of the debate. It is crucial to respect the consent terms under which data were provided, particularly when talking about historical data.

Qualitative Research Data

Protecting the rights of individuals who give qualitative interviews is also a concern. While the INDEPTH network does not collect qualitative data, the global debate on open access to data includes qualitative research. In one participant’s view, the risk is sufficiently great that qualitative data should be removed from the open-access discussion. These data, Herbst agreed, are inappropriate for direct access on the Internet and call for more protected, controlled data enclaves as an alternative.

U.S. Data Sharing

These issues can be covered, it was suggested, in policies that require agencies to have plans for sharing data in an environment that both protects proprietary rights and assures confidentiality and privacy. A participant noted that all U.S. science agencies are expected to have such plans. The plans do not provide open access to everything; indeed, some data are restricted because of the risk of re-identification if combined with other datasets. These concerns mitigate against a blanket approach to sharing all data, the participant noted.