2

Setting the Context

The workshop opened with two presentations that provided the context for how modeling could be used to improve population health. Steven Teutsch, who is an adjunct professor at the Fielding School of Public Health at the University of California, Los Angeles, a senior fellow at the Public Health Institute, and a senior fellow at the University of Southern California’s Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, first discussed why modeling matters to efforts that are aimed at improving population health. Ross Hammond, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution, then spoke on how models can be applied, including examples of how models have been used to inform policy and assess effectiveness. Following the two presentations was an open discussion moderated by Louise Russell, a distinguished professor at the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research and the Department of Economics at Rutgers University. Box 2-1 contains highlights from these presentations.

WHY MODELING MATTERS FOR IMPROVING POPULATION HEALTH1

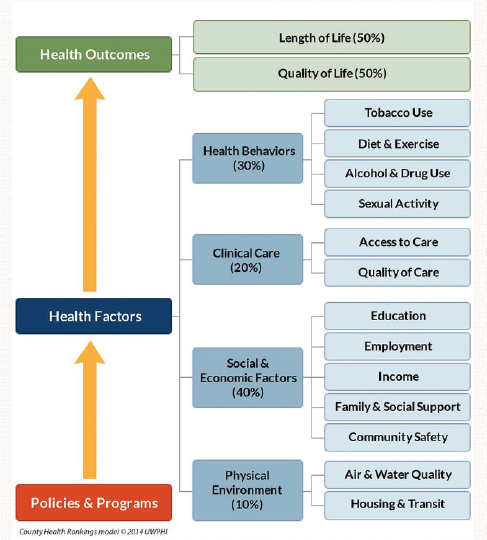

Steven Teutsch began the workshop’s first presentation by displaying the framework that the County Health Rankings2 uses to describe

___________________

1This section is based on the presentation by Steven Teutsch, an independent consultant; an adjunct professor at the Fielding School of Public Health, University of California, Los Angeles; a senior fellow at the Public Health Institute; and a senior fellow at the Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the Institute of Medicine.

2See http://www.countyhealthrankings.org (accessed September 24, 2015).

the many factors that drive health (see Figure 2-1). “The focus today,” Teutsch said, “is to begin to understand the kind of interventions that we can bring to bear and whether programs or policies can influence these factors and how they interact to improve the health of our communities.”

Interventions come in many forms, and, because of that, measuring their effectiveness can be challenging, Teutsch said. Interventions can vary in intensity and type, and they can interact in synergistic, duplicative, and complex ways with other interventions. It is important, but challenging, to make sense of those interactions and of the outcomes of interventions to begin to capitalize on those that provide the greatest value. Additional challenges in understanding the effectiveness of population health interventions arise from the long lag times between intervention and outcome, from the fact that many interventions are not amenable to randomized clinical trials, and from the fact that external factors can change over time, potentially limiting the relevance of long-term intervention studies.

Models can help address these challenges in a number of ways, Teutsch said. They can provide a way to synthesize the best available information about the many factors that contribute to health. Models

SOURCE: University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute (2014), presented by Teutsch on April 9, 2015.

can incorporate the primary concerns of decision makers, and, in that regard, it is important for modelers to interact with decision makers to identify the issues that are most important to them so that the models can be designed to provide meaningful and useful output. Models are often flexible and can be adapted to different situations, can incorporate the most up-to-date data and science, and can harness uncertainty. Models can also identify key research needs and answer “What if?” questions.

What models cannot do is provide definitive answers and make decisions on what to do.

The workshop planning committee had a long discussion about how to define a model, said Teutsch. The definition that resonated best with the committee came from the Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management (Gass and Fu, 2013): “A model is an idealized representation—an abstract and simplified description—of a real world situation that is to be studied and/or analyzed.” While models can be mental, iconic (such as an architect’s model of a building), analog, or mathematical, the workshop’s discussions would focus primarily on mathematical models, including those that account for economic factors, Teutsch said. “We will be talking primarily about how these models can be used to understand problems better and particularly how they can be used to influence decision makers,” he said.

To conclude his presentation, Teutsch reviewed the agenda for the workshop (see Appendix A) and then asked the workshop participants to keep some questions in mind. For the decision makers at the workshop, the questions included

- What important intractable or complex problems do you have that are not being adequately addressed by current approaches?

- Can models help? What kind of model would be best suited for the purpose? How should you be involved in the process?

- Have models been readily accepted by scientists and decision makers? What factors increased their acceptability and usability?

- How can results best be communicated to you?

For the modelers in the audience, the questions were

- What would you need to answer the questions?

- Do models need to be developed anew for each purpose or can we develop some more general models that can be applied to many questions?

- What human and financial resources will be required?

- How can models elucidate unexpected effects?

- How can modeling help us find the societal and health system return on investment both in economic terms as well as more broadly where returns could include improved health or social returns?

- How can modeling move us from an emphasis on health care to an emphasis on health?

- Can modeling help to develop a system to determine how and when to pay for the improvement in outcomes?

Teutsch also asked both groups to think about the data that will be needed to inform the models and whether those data are available. If such data do exist, he asked the workshop attendees to consider if there are any barriers to the use of those data. He also asked them to think about innovative ways to collect data that are not presently available.

BENEFITS AND USES OF MODELS3

“Anytime you are making a projection about how something you are doing to change a system will play out, you are in effect modeling that decision,” said Ross Hammond to start his presentation. In many cases, he said, these projections or models are implicit, but to inform policy it is often advantageous to turn these implicit mental models into explicit models. An explicit model, he explained, provides the ability to test the underlying assumptions that are built into the model and to explore the boundaries of when it is or is not a good representation of the system of interest. Explicit models also provide a means of exploring complex systems that are difficult to model mentally, he added.

Another reason to construct models, one that Teutsch had listed, is that they provide the ability to conduct experiments that may not be possible in the real world, Hammond said. Real experiments might be unethical or too costly to conduct, or they may take too long to complete in a meaningful period of time. Models can also address the heterogeneity across individuals, context, and time that may make it difficult to generalize from the results of a randomized controlled trial. Hammond noted that models have the potential to account for the unexpected changes to a system that can accompany an intervention or that occur in reaction to an intervention. For example, an intervention might be designed to reduce soda consumption, but if the result is that the targeted population substitutes consumption of sports beverages, it is not clear that the problem was addressed as intended. Similarly, an intervention aimed at reducing smoking could trigger an unanticipated strategic response by the tobacco industry.

Models can also help manage uncertainty and make it possible to consider alternative worlds that have not yet been observed or that cannot be observed. Examples that Hammond cited included forecasting what next year ’s influenza strains might be or what might happen with the implementation of a policy that has never been tried before, such as New York City’s recent move to raise the legal age to purchase tobacco to 21. “Models can help us think about these possibilities that by definition we

___________________

3This section is based on the presentation by Ross Hammond, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the Institute of Medicine.

cannot think about with existing data,” Hammond said. Another place that models can prove useful is in projecting how the processes of decision making or implementation of an intervention will proceed.

Policy making, intervention design, and decision making have all been guided by models, Hammond said, and there are three ways in which models have been used to do so. These methods are not mutually exclusive, and some models can serve multiple functions. The first way is to use models prospectively to try to understand in advance what the intended and unintended consequences of an intervention or policy might be. This type of application is sometimes referred to as in silico, as opposed to in vivo or in vitro, experimentation. In silico models can be useful for elucidating not only unintended consequences, but also potential trade-offs in terms of the synergy between different policy choices in a complex world. They can also help coordinate policy interests and policy actions across many silos in government or the policy world. These models do not eliminate uncertainty but merely help manage it, and they do not replace judgment.

As an example, Hammond discussed the Models of Infectious Disease Agent Study (MIDAS), funded by the National Institutes of Health. This modeling network developed multiple, independent models to inform policy choices and interventions designed prospectively, and Hammond said that it had a significant role in modeling the H1N1 influenza pandemic. The models developed by this network enabled policy makers and public health officials to consider the implications of choices made during that epidemic, such as closing schools and airports, distributing antiviral drugs, and distributing vaccine. “These are choices that had to be made in real time with high uncertainty and sometimes without a lot of data to directly guide them,” Hammond said. The models were able to leverage the data that were available, including data on the global airline network, sharing of patients and doctors across large hospital chains, and social networks, social contacts, and social structure, to produce forecasts on how influenza might spread across the globe. The models can include sophisticated representations of individual behavior and even biological data about how the disease might progress in individual people and affect contagion. “What you could do with a model such as this is to systematically explore many intervention choices and to understand how the pattern of the spread of the epidemic may be altered by what you do to combat it,” explained Hammond.

Another example that he discussed involved his work on models to inform decision making about point-of-sale policies for tobacco control. This model, called Tobacco Town,4 draws on existing data to try to

___________________

4See http://cphss.wustl.edu/Projects/Pages/Modeling%20Retailer%20Densityaspx (accessed August 17, 2015).

understand what the consequences of retailer-based polices might be, such as how changing the spatial distribution of retailers might impact the behavior of cigarette smokers and their purchase of cigarettes over time and to explore tradeoffs between zoning strategies and licensing strategies. The model is designed to forecast the magnitude of a policy’s effect and how quickly it might produce a measurable effect. It also considers unintended consequences, such as whether a policy might reduce overall access to tobacco while increasing already existing disparities, and it can help identify areas where further research is needed to better understand smokers’ purchasing behavior. To provide the workshop with a flavor of how the model works, Hammond showed a simulation of a physical geography of road networks in which people were moving around the space and purchasing tobacco. Altering the features of that simulated environment generated predictions about how individual responses might change over time.

A second use of models to guide decision making is to look retrospectively at interventions and policies that have already been tried with the goal of better understanding how these interventions and policies work—or why they did not work—and to leverage that knowledge to provide insights that would be useful for replicating or scaling an intervention or policy. In this context, Hammond said, “we are trying to understand why a particular policy has the impact that it does. This is not always clear in many real-world policy situations.” Successful interventions or policies can be modeled retrospectively, and results from those models can then be used in prospective models. An example of conducting a retrospective model and using the information from that model prospectively can be found in obesity prevention at the community level, an area in which significant investments in interventions are being made. Some of these interventions work well in one setting but not in others when they are replicated, and understanding why this is the case is important for designing interventions that are appropriately tailored to context and that can apply existing evidence to produce better outcomes. The model that he described is now being used prospectively to design an obesity intervention that will be tested in the field. Hammond noted that this type of modeling has also been used to better understand corruption, crime waves, retirement decisions, and childhood literacy, among other areas of study.

The third way that models are used to guide decisions involves focuses on etiology, and when used properly, this type of model can help reduce the uncertainty that decision makers face when developing policies by helping them understand the mechanisms that are at work. Such models do not explicitly model a policy but nonetheless have implications for policy and intervention design and can also help identify data

gaps. The MIDAS models that Hammond mentioned, for example, have been used to study the adaptive behavior of people during epidemics. Another modeling effort focused on the neurobiology of eating and how preferences are formed that can persist over long periods of time. Some of this work, Hammond said, has important implications for identifying windows of when to intervene, how to go about intervening, and how the same intervention might work differently for different people. Another obesity-related model examined how social norms about obesity have changed. This model, Hammond said, might provide hints about how that process could be applied to design interventions aimed at social network structure.

Hammond stressed that there are many promising ways to use models to inform policy, but with the caveat that it is not easy to do so, and, in particular, not easy to do well. The workshop, he said, would highlight some of the great successes in this area, but he also noted that there are good models that have not made a difference in decision making as well as models that did make a difference in decision making but that turned out to be flawed in important ways. “It is good to have the big picture in mind,” he said, “and to know that there are best practices that need to be followed in order to do modeling well so that the results are dependable, reliable, and meaningful and that they answer the questions that policy makers and decision makers have.” He said that there a number of publications available that detail those best practices. If the goal of a modeling exercise is to address policy questions, for example, one best practice is to engage early with policy makers or decision makers to determine that the question a model will answer is one that is important to answer. Best practices also exist to help modelers decide what to include and what not to include in their models and to plan testing and implementation procedures.

Another reason for engaging early with policy makers and decision makers, Hammond said, is so that they develop a deep understanding of the model and become stakeholders in the model development in a way that gives them a more intuitive sense of why the model comes up with a certain result, particularly when that result is counterintuitive. For example, one of the MIDAS models showed why closing schools during an influenza pandemic might be a bad idea—it would reduce the number of health care workers that would be available since many health care workers are single parents and would have to take time off if their children were not in school. Another counterintuitive finding was that if there is a limited supply of vaccine available and the goal is to protect the elderly, the best course of action could be to give none of the vaccine to the elderly and give all of it to school-age children, who turn out to be the primary transmission pathway. “This would be a scary result for a policy maker to act on without having confidence in the model,” Hammond said.

In closing, he said it is important to keep repeating the idea that models help manage uncertainty but that they do not remove it and they do not replace judgment. For policy makers and decision makers, it is also important to think about the appropriate uses for different types of models and to get involved early on in the model-building effort.

DISCUSSION

Christine Bachrach from the University of Maryland opened the discussion by asking Hammond to comment on the issue of how certain one has to be about the causal relationships among the parameters that are included in a model. The answer, Hammond said, depends on the model’s intended use, and he added that this is a particularly vexing question if the goal is to make real-world decisions that have potentially big consequences. There are, however, strategies to address this challenge. All models, he said, are essentially making causality claims, so the question is whether the causality that is implicit in a model also holds true in the real world. “To assess that,” he said, “you have to use a variety of testing approaches with your model to understand what evidence is based on and what it does or does not show about what we know in the real world and what it can reproduce in the real world. That said, it is important to recognize that by design, models are simplifications, which means that they are all missing something important that is true in the real world.”

George Isham from HealthPartners observed that, based on his experience as a model user and policy maker, policy makers need to be much more engaged in model development if they expect to get the kind of in-depth information that is useful in making policy. At the same time, he said, policy makers do not often have the time to engage as fully as they need to because they are making policy across a thin range of issues that do not go deep into any one area. In addition, most policy makers do not know the right questions to ask regarding the right type of model to use. He suggested that there needs to be a general primer for policy makers that they can read before engaging in any kind of modeling activity, and he wondered if the modeling field is at the point that large-scale computing was before the advent of the personal computer, where modeling is still in the hands of the experts.

Regarding the need for a primer, Hammond said that there are a number of resources, including several Institute of Medicine reports, available to help with the process of asking the right questions. He also said that many successful interactions between modelers and policy makers involve what he called translators, individuals who are conversant in the languages of the policy world and the modeling world. The MIDAS pro-

gram that he mentioned benefitted from such individuals, he said. With respect to Isham’s last point, Hammond acknowledged that there is some tension in the modeling community concerning the idea of participatory modeling and how to make communities and policy makers partners in the modeling enterprise. Louise Russell added that a good model has to be the result of a conversation not just between modelers and policy makers, but also one that includes subject matter experts.

Catherine Baase from The Dow Chemical Company asked if models have confidence intervals that reflect the fact that they include assumptions when the exact information needed is not available and if there are ways of tracking the effectiveness of models over time. Hammond replied that the answer is yes to both of those questions. “There are ways to develop what you might describe as a confidence interval for the results of a model, the degree of uncertainty that is inherent in different estimates that the model is making,” he said. “There are also ways to handle uncertainty about the inputs to a model by doing sensitivity analysis and exploring how much the results depend on different assumptions that you are making, which can be very important when there is unavoidable uncertainty in the real world.” In his opinion, he said, an important part of modeling is to be clear about variation in the results of the model and the causes of that variability. “That is actually the most critical information in some sense for a decision maker.” Russell added that this is a place to involve subject matter experts, as they can not only help to identify the best available data for a model (and the standard errors that represent the uncertainty in even the best data) but also help to develop estimates and ranges to represent uncertainty for those features of a model for which there are no good data.

James Knickman from the New York State Health Foundation asked where this type of modeling was taking place, and Hammond replied that it is widely distributed. Teutsch agreed and noted that governors’ offices, in particular, are active developers and users of models for policy analysis. Knickman asked if there is an inflection point coming in the modeling world, and Hammond replied that in some ways the answer is no because much of the modeling that is done now is a natural extension of modeling approaches that have been around for a long time. He did say, though, that there are some relatively new approaches that are being developed in the modeling world, many of which are aimed at breaking down the wall between disciplines and across agencies in the policy space and that take a more systems-based approach to modeling that is new in the public health world.

Sanne Magnan from the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement asked Hammond and Teutsch if they had any thoughts about how to marry the gaming world with the modeling world to democratize model-

ing and give consumers more power to use models to examine the effects of their decisions on their health. Teutsch replied that the tools of modeling are moving out of the sophisticated research setting and on to the Web in ways that will empower individuals to work with these models. In his view, models are intrinsically synthetic rather than reductionist, and they will move society away from medical models that are reductionist to a place where people start considering the complex interactions of the factors that influence their health and that are outside of the interventions now associated with the medical model of health. “I do think there will be empowerment that comes along with this,” Teutsch said. Hammond added that models can be fabulous teachers and said that he hopes that students start learning about and using models in high school or even before rather than when they are in graduate school.

Steven Woolf from Virginia Commonwealth University’s Center on Society and Health asked the speakers if they could comment on the role of big data and machine learning in modeling. Hammond replied that when he thinks about big data, the questions that he asks are “How do you know what is the right data?” and “What do you do with it once you have it?” He said that it is not immediately clear that the data collected today are the right data to collect and that, even if they are, the act of translating them to something that is policy relevant can be difficult. Machine learning, Hammond said, is another form of modeling with its own advantages and disadvantages.

Pamela Russo from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation noted that the Foundation used to run a program called Young Epidemiology Scholars and that each year the projects selected as finalists included what she characterized as brilliant models developed by high school students. She also commented that she was involved in a project that developed a model with many assumptions that were clearly stated and transparent and which the users could change when they ran the model. She asked the panelists if that type of transparency adds to the confidence in a model. Russell replied that such transparency is a good idea and that even if the model is not set up to be easy for non-modelers to change, it should be possible for them to ask the modelers for information about the assumptions and for results that show what would happen if those assumptions were changed. “That is what sensitivity analysis is about,” Russell said, “That is what policy makers, other users, and subject matter experts need to keep an eye on.”

This page intentionally left blank.