4

What Would Public Health

Decision Makers Like from Models?

This portion of the workshop first featured a context-setting presentation by Gary VanLandingham, Director of the Pew–MacArthur Results First Initiative, in which he gave an overview of that initiative. After that the workshop participants broke into four groups to discuss what modelers working in four different areas of public health would most want from models. The four areas were

- health risk factors, such as obesity and substance abuse;

- natural and built environments, including air and water quality, transit, and housing;

- social and economic conditions, including such factors as education, income, and discrimination; and

- integrated health systems, including such influences as community conditions and available clinical services.

Rapporteurs from each group presented the main points identified during the group’s discussions, and an open discussion moderated by Steven Woolf, a professor of family medicine and population health and the director of the Center on Society and Health at Virginia Commonwealth University, followed the report-outs. Box 4-1 contains highlights from these presentations and discussions.

MODELING EVIDENCE-BASED PROGRAMS IN MULTIPLE POLICY AREAS1

The goal of the Pew–MacArthur Results First Initiative, a joint program of the Pew Charitable Trust and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, is to bring modeling into the public arena in a way that makes sense given today’s political dynamic. To do that, Gary VanLandingham said, it will be important to answer in real time the toughest questions that policy makers have covering a wide range of issues. The challenge with traditional modeling, he said, has been that it only answers pieces of a question, while policy makers want more inclu-

___________________

1This section is based on the presentation by Gary VanLandingham, Director of the Pew–MacArthur Results First Initiative, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the Institute of Medicine.

sive answers because of the limited time they have to make decisions and their desire to avoid political conflict.

Once a program gets created, VanLandingham explained, it tends to go on autopilot, and little attention is paid to what it is accomplishing until some crisis develops. “When a crisis occurs,” he said, “what policy makers think about is what else they can do now in addition to everything else they are doing to try to get the inflection that they want to have. “What Results First is trying to do is step back and ask the questions, ‘What are we doing now?’ ‘Does it make sense to do these things?’ ‘Are there other opportunities that research has shown to be effective?’” By answering those questions, he said, Results First hopes to help policy makers make decisions in a much more informed way than they have been able to do in the past.

Results First has been focusing on states and equipping them with the ability to answer questions in a more comprehensive manner using data from real-world programs, VanLandingham said. Results First has been using data in national research clearinghouses relating to a number of policy areas as well as the work of the Washington State Institute for Public Policy, which has been developing a portfolio-based cost–benefit analysis model over the past 15 years, focusing on outcomes and return on investment. Currently, Results First can assess interventions in some areas of health care as well as interventions for adult and juvenile justice, child welfare, substance abuse, mental health, and education ranging from early education through 12th grade. Program leaders are starting to explore expanding into the public health arena to help inform decisions there as well.

The general approach that Results First takes, VanLandingham said, is to start with the best research from evidence-based programs that identifies what works, use econometric models to understand what happens in terms of effect sizes, and then use those results to predict the impact of a large variety of interventions, again using the same econometric modeling methods. The goal, VanLandingham said, is to give policy makers an apples-to-apples comparison of what happens if they take one course of action versus another within a given policy environment. If a policy maker is concerned about rising crime rates, for example, the model provides a comparison of different interventions that have been shown to reduce recidivism in other places in the United States and estimates what their effect might be in that policy maker ’s state. Results First lets policy makers identify how they will spend their money, given what is known about the possible interventions and what the possible return on investment will be. This information is supplemented by an analysis of currently funded programs that are matched against the national evidence base, recognizing that there is a continuum of evidence about a given program’s effectiveness.

“Unfortunately, there are programs that we know about that make things worse, and there are homegrown programs that nobody knows anything about,” VanLandingham said. “The question that we pose to policy makers is if they are happy with putting half of their money into interventions if nobody knows if they are working when there are other programs out there that we can predict will work.” That is not to say that Results First advocates against homegrown programs, he said, but it does ask policy makers to test them and subject them to the same assessment that other programs with known effectiveness have gone through so that they can feel confident that they are getting the best return on their investment.

To illustrate the kind of analysis that the Results First program generates, VanLandingham discussed an assessment of community-based functional family therapy for juvenile offenders. The best research available shows that children who go through this program have a number of positive outcomes and that crime drops an average of about 22 percent after the program has been completed. Children who go through this program are more likely to graduate from high school, which in turn means that they are more likely to be employed, have health insurance, and have lower health care costs (see Table 4-1). On average, this program generates more than $37,000 in benefits per child at a cost of just more than $3,300, for an 11-fold return on investment, which VanLandingham characterized as a good deal for a state. The question, though, is how this compares with other options for dealing with youth offenders.

The Results First team looked at 10 additional programs and ranked them by their cost–benefit ratio (see Table 4-2). Some of these programs,

TABLE 4-1 Cost–Benefit Analysis for Community-Based Functional Family Therapy

| Outcomes from Participation | Amount | Main Source of Benefits |

| Reduced crime | $29,340 | Lower state and victim costs |

| Increased high school graduation | $9,530 | Increased Earnings |

| Reduced health care costs | $398 | Low public costs |

| Total benefits | $37,587 | |

| Cost | $3,333 | |

| Net present value | $34,254 | |

| Benefits per dollar of cost | $11.28 |

SOURCE: VanLandingham presentation, April 9, 2015, based on benefit–cost data reported by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy (see http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/BenefitCost [accessed September 25, 2015]).

TABLE 4-2 Cost–Benefit Analysis on a Portfolio of Programs Aimed at Juvenile Offenders

| Programs | Cost | Long-Term Benefits | Benefit/Cost Ratio |

| Adult Programs | |||

|

Cognitive behavioral therapy |

$419 | $9,954 | $24.72 |

|

Electronic monitoring |

$1,093 | $24,840 | $22.72 |

|

Correctional education in prison |

$1,149 | $21,390 | $19.62 |

|

Vocational education in prison |

$1,599 | $19,531 | $13.21 |

|

Drug court |

$4,276 | $10,183 | $3.38 |

|

Domestic violence treatment |

$1,390 | –$7,527 | –$4.41 |

| Juvenile Programs | |||

|

Aggression replacement training |

$1,543 | $55,821 | $37.19 |

|

Coordination of services |

$403 | $6,043 | $16.01 |

|

Drug court |

$3,154 | $11,539 | $4.66 |

| Scared Straight | $66 | –$12,988 | –$195.61 |

SOURCE: VanLandingham presentation, April 9, 2015.

such as cognitive behavioral therapy, are relatively inexpensive to implement and provide good outcomes, while others, such as Scared Straight, are relatively inexpensive and produce terrible outcomes. “Scared Straight is a very good program if you are trying to increase crime,” VanLandingham said. “Research shows kids that go through that program are more likely to commit crime and more likely to commit more serious crimes than kids we leave alone.” He added that the message to policy makers is that there are some programs they fund that simply do not make sense.

The model allows the users to do what-if scenario testing using Monte Carlo simulations which produce a probability distribution for achieving a positive return on investment. VanLandingham noted that sometimes there are political reasons for choosing one program over another, but the goal of the Results First program is to make a compelling case for not making bad policy decisions.

Results First has been testing its models for 3 years and is now working with 17 states and 4 California counties to build their own capacity for conducting these analyses in an ongoing manner. Over the past 2 years, five states have moved about $80 million in funding, both new money being spent on programs that have been shown to produce positive returns on investment and also money reallocated from programs that produce negative or small impacts. In at least some cases, these

poorly performing programs are not working because they have been implemented poorly. “This is trying to pay attention to the fact that implementation matters in evidence-based programs,” VanLandingham said.

He reiterated that the main focus to date has been at the state level because the actions that states take have significant real-world impacts. He also noted that Results First recognizes that there are real challenges in bringing modeling into the policy process, and he said that the program’s strategy is to put these models in front of the people who are actually making policy, such as those in state budget offices and state legislative research offices. He noted that the best people to work with are those who have honest broker status and who have the technical skills required to look at the results of these models and understand their implications. Another reason for working with people inside the process is one of timeliness—these reports have to be ready when policy makers are making their choices, not a week later. To have the biggest impact, VanLandingham and his colleagues have found that they have to engage in ongoing outreach and training with staff and legislators.

In his final comments, VanLandingham offered a few ideas for making modeling easier. His first suggestion was to identify what is known about these interventions and to encourage the research community to look at outcomes and not just implementation. Results of studies that are properly powered are applicable on a bigger scale. There is also the issue of dissemination. “Good outcome studies often never come to the attention of people who could use them because the results only go to funders,” he said. “They do not go out to the research clearinghouses, and they are not published for a variety of reasons.” Solving the dissemination problem is essential if the goal is to have more research available in order to better understand what programs work and which ones do not. Better coordination between the research and modeling communities will enable research programs to generate the data that modelers need to convince policy makers that a program is worth doing. For example, program evaluations rarely include information about implementation cost.

In response to a question from Catherine Baase about how Results First selected which states to work with, VanLandingham said that when the program started 4 years ago he and his colleagues made presentations at policy forums such as the National Conference of State Legislatures and the Council of State Governments and then asked anyone who was interested in participating in the program to get in touch. At first, he and his team worked with anyone who expressed an interest, but now there is a much more rigorous selection process which requires a formal invitation from a state that is willing to make a high-level policy commitment, such as a letter of invitation from the governor and presiding officers of the

legislature. “We think it makes more sense to have exemplar states than to be in 50 states and 400 counties,” VanLandingham explained.

The long-term plan for the program is still unclear. “We think this is where the field needs to go, and we think that the technology is available now and the research is available now,” VanLandingham said. What he and his team are doing now is trying to develop the best plan to move the field to embrace modeling. “My goal is at the end of the day that people will not think about putting money into a program without asking the question of what is going to happen and to make better choices on how to spend limited amounts of money to meet big needs,” he said. “We are seeing our best states asking those questions now, and what we want to see is for that to happen across the country.”

REPORTS FROM THE WORKING GROUPS

After VanLandingham’s presentation participants broke into four working groups to explore how modeling could be used to inform population health decisions. As noted earlier in this chapter, the four working group topics were

- health risk factors, such as obesity and substance abuse;

- natural and built environments, including air and water quality, transit, and housing;

- social and economic conditions, including such factors as education, income, and discrimination; and

- integrated health systems, including such influences as community conditions and available clinical services.

The following sections recap the comments of the working group rapporteurs who summarized what they had heard from the individual working group to which they were assigned.

Before the working groups began their discussions, Steven Woolf from the Virginia Commonwealth University provided some guidance to the participants. He said that the overall objective of the discussions was to identify opportunities, barriers, and innovative approaches for using modeling to inform population health. The objective for decision makers and population health researchers was to gain a better understanding of where and how modeling could be a useful tool to inform decisions and identify data and research needs. The objective for modelers was to gain a better understanding of where models are needed in population health and of the complex nature of the priorities in the field. The groups were provided with a list of starter questions, including

For policy makers and population health researchers:

- What are the main evidence gaps you encounter? Where do you need more support to inform your decisions, and where would the results from quality modeling exercises help you, both with making decisions and with relaying to others the importance of a potential decision?

- What are your concerns about using models?

- What is intriguing to you about using models?

- If you have used models, how have they been useful to you?

For modelers:

- Based on the expressed needs of the policy makers and researchers, how do you think modeling could be helpful?

- What information would you need from policy makers and researchers?

- What types of data (both qualitative and quantitative) would you need?

- How resource intensive (in terms of both funds and human capital) should the modeling be expected to be?

- Are there models that could be developed relatively quickly for these issues, or would they be a long-term endeavor?

During his comments Woolf asked the groups to make note of data gaps and barriers, of communication requirements and challenges, of ideas on how to build trust in results and capitalize on the information from models to drive change, and of opportunities for policy makers be involved in the modeling process.

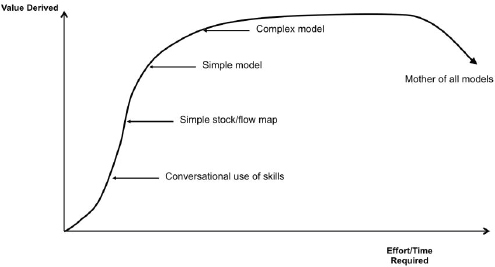

Health Risk Factors—Report Back2

George Miller, a fellow at the Altarum Institute’s Center for Sustainable Health Spending, presented the report from the health risk factors group. He showed a “value per effort” graph (see Figure 4-1) that illustrated the idea that as models become complex, it takes more time and effort to create them and that, up to a point, the additional time and effort provides more value. At some point, however, a model becomes so complex that it loses transparency and, as a result, no longer provides what good models should—valuable insights about the modeled system rather than simply a numerical output.

___________________

2As summarized during the activity by participants and rapporteur George Miller, fellow, Altarum Institute.

SOURCES: Peterson, 2003, used with permission; Miller presentation, April 9, 2015.

To stimulate the group’s discussion, Karen Minyard from the Georgia Health Policy Center prepared a list of guiding principles for modeling health risk factors that Miller said would also be good guiding principles for modelers to remember when working with decision makers. This list highlighted the fact that models, which are tools to enable thinking about complex systems, are most effective, accepted, and useful in catalyzing change when the following factors hold

- the purpose for using a model is clearly identified and supported by the client;

- it is developed in a collaborative process among the modeler, the stakeholders, and the subject-matter experts;

- the model is as simple as possible, but no simpler;

- it can be tailored to the readiness and level of engagement of the participants as well as to the goals and outcomes of the process;

- the modeler or facilitator has the adaptive and technical skills to use these tools; and

- the model is used as part of a larger change process.

One point made during this group’s discussion about readiness and engagement was that sometimes there is no need for a model, as in the case when there is strong empirical evidence for a decision and the decision makers are onboard. At other times, there may be a great deal of information available about a potential intervention, but a model can

help organize that information and coordinate it in a way that allows the various stakeholders to share a mental model about how that information interacts. Another point raised during the discussion about models needing to be part of a larger change process was that decision makers need to be able to understand a model’s output in the context of their environment and their experiences. Miller noted, too, that if a model simply tells stakeholders what they think they already know and provides no new insights, then it has not made much of a contribution to the decision-making process. “I think there is a tradeoff between making sure that the results are understandable and having the richness that will provide new knowledge as well,” he said.

Several members of the group commented that modelers need to know how to talk to stakeholders and decision makers—and, in particular, to know how to translate the results of their modeling for these audiences. It is also important for modelers to be good listeners, Miller said. Solving the right problem, one that matters to stakeholders and decision makers, is important. For example, if a model shows what an intervention might do to change a risk factor, but what the decision maker wants to know is what the economic impact of that intervention will be, then the model has not gone far enough to support a decision.

When the discussion turned to changing health risk factors, the point was made that models can show decision makers how to trade off interventions in different sectors. Miller said that this is particularly true for upstream population health interventions. In part, the need to inform decision makers about these trade-offs results from the way that legislators work, which is to make decisions about where to invest in different sectors such as health, education, and transportation, but it also arises from the fact that these upstream interventions will interact with one another to affect population health in complex ways that a model might help policy makers understand.

The group engaged in some discussion about the interest and importance in understanding the longer-term impacts of some of the interventions, particularly those that operate on a population health level, where much of the value comes over the long term. There is, however, a tradeoff between short-term and long-term concerns because legislators have to worry about budget cycles and therefore have a shorter-term focus, Miller said. It was noted during the group’s discussion that models tend to discount the future, which is appropriate because it is more difficult to understand the distant future than the near future. One member of the group did point to an example of a legislator who used model results to have the courage to make recommendations for a long-term investment which might not have otherwise been made in the usual context of having to worry about short-term budgets. There was also some discussion

concerning diabetes prevention, with the suggestion made that modeling efforts could focus on upstream interventions that occur even before the pre-diabetes stage of disease development.

Natural and Built Environments—Report Back3

J. T. Lane, the assistant secretary for public health for the State of Louisiana, who served as the rapporteur for this natural and built environments work group, said that two themes had emerged from this group’s discussions: (1) Modeling has proven that it is reliable for examining long-term problems and concerns, and (2) there are limitations when it is applied to more immediate needs, such as modeling an infectious disease outbreak as it occurs. Several members of this discussion group noted that the modeling community needs to develop better tools for immediate-term situations. The development of such tools could lead, for example, to a future in which American families turn on the morning news to get the day’s influenza forecast, just as they now get the day’s weather forecast.

Much of the group’s discussion regarding barriers focused on regulatory issues, but some group members also noted that there are resource gaps in terms of trained individuals and finances for governments and organizations that still need to adopt modeling. There may be opportunities to address both of these resource gaps, Lane said, by developing partnerships between these organizations and academia. Educating the policy community and the public about the use, value, and limits of modeling is also important. Lane said that one thing he has learned as a state health official is that policy makers often want to move forward on an initiative in large part because of the projections or modeling activities that they have been privy to, but that there is still a need to spend the time to go out to the public, sell that idea, and explain what the model means and does not mean. Part of that sales job includes educating members of the public about the model so that they can understand how policy makers decided that an initiative will serve the public good and will provide a good return on investment. The last barrier identified during the discussion by several group members was one of high expectations—that is, that there is an expectation of certainty in the public sphere. To address this, some group members said, the modeling community ought to reinforce the message that models are decision helpers, not decision makers.

The group discussed the possibility that models may be stifling innovation because they are based on evidence accumulated from projects that have already been completed, rather than challenging convention. Even-

___________________

3As summarized during the activity by participants and rapporteur J. T. Lane, assistant secretary for public health for the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals.

tually, however, several members of the group noted that models can in fact serve as a source of innovation because once a model becomes robust enough, it becomes possible to change the model’s assumptions and system features to incorporate novel ideas and test new theories. Another opportunity identified, Lane said, would be to use models to develop priorities for collective future action and benefit to communities and to explore more deeply and systematically whether it would be possible to model the effects of social and cultural values on health concerns. One example given was to examine burial rights in West Africa and the impact of that cultural practice on the spread of Ebola. Lane characterized this challenge to the modeling community in this way: How can we modify our models in a scientifically sound way to account for, quantify, and give value to cultures and beliefs in society and thus make our models more accurate and responsive?

Social and Economic Conditions—Report Back4

Nick Macchione, the director and deputy chief administrative officer for the County of San Diego’s Health and Human Services Agency, served as the rapporteur for the social and economic conditions working group. This group first discussed data needs, he said, concerning the social and economic enablers of health, the relevant data need to be collected from many different sectors. Some participants in the group suggested that the modeling community could capitalize on opportunities for capturing and using “big data” and that the open-source data movement offers some great opportunities to address data gaps. At the same time, modeling may be able to help consolidate and make sense of data from disparate sources.

One concern that Macchione voiced from his perspective as a policy maker is that there is a need to humanize models for the policy community, to express the output of models in terms of real people and real lives that can grab the hearts and minds of policy makers. This is particularly true, he said, for the human services area which deals with emotional and life-threatening issues such as child and spousal abuse.

When the group discussed the types of models needed, several participants in the group noted that the social and economic conditions area needs models that compare interventions as well as models that look at the synergies of multiple interventions. To address this latter need, the community could involve experts in systems science. Individual partici-

___________________

4As summarized during the activity by participants and rapporteur Nick Macchione, director and deputy chief administrative officer for the County of San Diego’s Health and Human Services Agency.

pants in the working group shared questions that could benefit stakeholders and modelers in setting goals together:

- What are models needed for in the domain of social and economic conditions, given that this is an emerging area for modelers?

- Is modeling a barrier to adopting necessary decisions in this area?

- What common features of models can be borrowed from other, more developed areas of modeling?

One of the issues that the group discussed was how to sustain a great model once it has been implemented, given the funding environment in most state and local governments. One solution, Macchione said, might be to use open-source models, something that his office and public sector policy groups across the country are currently examining. Communication is another issue, he said, particularly with regard to policy makers’ expectations and their tendency to look at the short term rather than the long term. Many policy makers would like models that can be developed quickly. The fact that not all models are interactive is a problem—simply handing policy makers a model’s output has limited impact—and moving toward an interactive standard would be beneficial, even though it would also be challenging.

Several members of the group commented that modeling can help bridge gaps across different professions, which generally each have their own educational background, intellectual biases, and approaches to problem solving. Modeling can also make it possible to have conversations across professional cultures, though several members of the discussion group said there is a need for translators who can move among subject matter experts, modelers, and policy makers. There was some concern within the group that the field may need to pay more attention to the core competencies of those translators in terms of how well they can translate science and communicate, convene, and influence conversations among the different constituencies.

Skepticism about modeling is a potential barrier, and addressing it will require that modeling becomes more formalized to ensure trust. The field would also benefit if modelers better communicated what they have done to ensure the quality of their models. As some of the workshop’s presentations had highlighted, some members of the discussion group said that it is important to engage stakeholders early in the modeling process to increase transparency. Well-trained translators can serve an important role at this stage by helping to bridge the language gap that can work against transparency.

Concerning next steps, several participants in this group stressed the importance of starting the modeling process by engaging the policy-

making community and other stakeholders to identify the questions that need answering and to think hard about where and how modeling can have an impact in this area. Some members of the group said that using health and wellness in all policies as a tool forces stakeholders to look at these issues through many lenses and helps them identify the essential data elements that need to be collected to create the most robust and useful models. Macchione added that modeling in the domain of health and human services could also be useful in helping identify causal pathways, which might be more concrete to a policy maker.

Integrated Health Systems—Report Back5

The final working group’s report was delivered by Louise Russell, a distinguished professor at the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research and the Department of Economics at Rutgers University. Russell said that this group’s discussion hit on many of the same themes as the other groups did. She recounted two examples that group members discussed which illustrated some of the challenges that come with modeling. The first example involved work on breast cancer screening by the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. Based on simulation modeling of different screening strategies, the task force recommended a change in the guidelines for breast cancer screening. However, Russell noted, the public’s reaction was almost uniformly negative, illustrating the importance of education and the need to involve all stakeholders early in the modeling process.

The second example, explained Russell, involved a model of community action, developed and funded by the Kellogg Foundation, which had some stringent requirements on community involvement. Every program that accepted funding failed except for one, and that program succeeded because, after assessing how community involvement was to take place, it decided to return the money and not even try to use the model. This group, Russell said, realized that a community organization structure already existed and that forming a new one, which was a requirement for funding, would lead to failure.

Involving the community early before the modeling effort begins in a necessary step. Deciding who needs to be represented can be a challenging task, but it is an important one because if the community does not trust the process, the model is not going to have an impact. Once the stakeholders are identified, the next step is to bring them together

___________________

5As summarized during the activity by participants and rapporteur Louise Russell, distinguished professor in the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy and Aging Research and the Department of Economics at Rutgers University.

to help define the problem to be addressed, to settle on what the community wants to accomplish, and to identify the interventions that the community would be willing to consider implementing.

When developing systems models, it is necessary to draw boundaries about what to include in these models and, again, to involve all stakeholders in this decision. The real question, Russell said, is what the people involved want to see from a model. “Every model is a simplification,” she said, “but what simplifications are they willing to live with and what are the things that stakeholders think absolutely must be in the model?”

Another key point raised by some members of this group was the importance of timing in implementing a new intervention. For example, a model may find that a particular intervention will be far more effective than the one currently being used, and both policy makers and stakeholders may agree to end the current program and start the new one. In the real world, however, programs do not suddenly end, and new programs do not begin at full speed, There is usually a period which models do not consider when a new program is being put in place and the original program is being phased out, and the existence of this period means, among other things, that funds and resources cannot be shifted immediately from one program to the other.

This group also discussed the importance of establishing good channels of communication among modelers, those who inform models, and the public, particularly with regard to the mental models that members of the public already have in their own heads, such as the public’s model for breast cancer screening. In that case, the public’s model assumed that early screening for breast cancer was always good and that screening was nearly perfect—ideas that experience with widespread screening had called into question. The scientific evidence about early detection and screening needed to be communicated to the public before putting that evidence into a model, Russell said. That meant, once again, sitting down early with stakeholders to determine the common knowledge base and where knowledge gaps existed. Some participants in the group did note, though, that the public is coming around to the task force’s recommendation on breast cancer screening, and it is likely that putting out its recommendation based on modeling started a necessary conversation.

The last point brought up during the discussion was that it is possible to start the conversations with stakeholders in a harmonious rather than a confrontational mode. One way to do that would be to start the conversation with a conceptual model and an overview of the scientific evidence supporting the model.

DISCUSSION

Steven Woolf started the discussion session by making an observation that he said he suspected almost everyone was thinking. He had expected, he said, that the key challenges brought up by the group members would have been about technical and difficult methodological problems and complicated data infrastructure issues that need to be addressed if modeling is going to be exploited to improve population health. Thus, he said, he was surprised by the degree to which all of the groups had emphasized the need for increasing the engagement of stakeholders in the community and the importance of communication in successful modeling. “I think we often give lip service to this point,” he said, “but I think part of what I’m hearing is there’s a need to take this to the next level in terms of sophistication.” Woolf likened this situation to that of patient engagement and patient-centered care. People talked about these issues for years, he said, but it was not until funders such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute started taking that discussion to a new level of sophistication that serious and genuine engagement started to occur. The thesis he heard from the four working groups, Woolf said, is that efforts to use modeling to improve population health have to get serious about engaging stakeholders at the very beginning of the process, getting them to define the problems that need addressing and to decide whether a model is even needed, and then keeping them engaged throughout the process.

David Kindig from the University of Wisconsin noted that all of the discussion so far at this workshop had been about models in the public policy sector, and he said he wondered if there were any examples from the private sector, particularly from private health care organizations, that could contribute to the public health area. Russell said that she does not know much about the models that corporate America uses for health care decisions because they do not make them public. Macchione said that the Building Industry Association in San Diego—as well as the San Diego Association of Governments—has done economic modeling to identify the impacts of the construction industry’s activity on the economy, job growth, and crime in the areas in which it is building. He added that he knows of many examples of modeling in the private sector but said that he has not studied those models other than to know that private sector entities use them in what they call “business engagement.” Business engagement is very similar to the community engagement discussed at this workshop in that business get their end users involved in their modeling projects to make sure that they are looking at the right problems and to achieve the most efficient and effective solutions.

George Isham commented that he believes there is an opportunity with regard to community benefit investment decisions that are made by hospital boards of directors and chief executive officers to get some

estimates of returns that could then be used in models. “That would be a very specific example and tangible example of private policy making or decision making,” Isham said, adding, “We use the term ‘policy making’ to refer typically to legislators and governmental policy making, but the premise of the roundtable is that the task of improving health in the country is so complex that it is multi-sector and it requires private policy making as well as public policy making if we are to see an impact.” Along those lines, it is important, Isham noted, to educate private boards of directors that the prevailing mental model of health—which assumes that health and health care are the only two factors involved—is not correct and that health care accounts for only 20 percent of the contributors to health. Getting boards of directors to understand this reality could change the way that they construct their business models to reach beyond health care delivery into the community to form partnerships to address the other 80 percent of the factors that influence health.

Isham then wondered if there is a way to use this broader mental model to think about the research and rigor needed to model the relationships between education and health—for example, to influence investment decisions by both the private and public sectors. Rajiv Bhatia from the Civic Engine said that while the health care industry is investing a great deal of money in analytics and predictive modeling, it is notable how little of that modeling is focused on upstream population health risks. His conclusion from this situation is that the health care industry does not yet see population health to be an economic risk.

The final comment in the discussion came from Pamela Russo, who wondered if the reason that public health is “behind the curve” in using models to influence policy, other than in the area of tobacco control, is that there is a higher bar for rigorous evidence in public health policy than in other areas, such as economic modeling. Russell responded that the models used for policy making in areas other than health are reviewed just as rigorously.

This page intentionally left blank.