The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is a large and complex organization, with 24 different Institutes and Centers (ICs), each with a different mission and different needs. Although SBIR/STTR is managed by the NIH SBIR/STTR Program Office, all awards are made by individual ICs, using procedures that they themselves largely determine.

This chapter describes a number of aspects of SBIR/STTR program management. It addresses the processes through which awards are solicited and funding decisions are made. It also focuses on some of the initiatives developed by NIH to support these processes, such as the commercialization training and support program and efforts to attract new applicants. The focus on the selection process reflects the fact that it was the subject of concern for case study companies and many survey respondents. The funding gap between Phase I and Phase II receives attention, because it can have a seriously negative effect on small companies. The chapter also describes some of the challenges facing award recipients, notably in relation to the clinical trials through which almost one-half must work before they can sell their products commercially. Finally, the chapter considers data collection and analysis, which is a core element in an effective and data-driven program.

A COMPLEX PROGRAM

The assessment of the NIH SBIR/STTR programs is made more challenging by the growing complexity of funding mechanisms at NIH in recent years. Expanding beyond the original Phase I/Phase II grants, the programs now include Phase I/Phase II grants, Phase I/Phase II contracts, Fast Track awards that include both Phase I and Phase II, Phase IIB awards, Bridge awards, Direct to Phase II,

and supplementary awards. These different awards are discussed in this chapter. Table 2-1 shows the number of awards and amount of funding provided through Phase I, Phase II, and Fast Track for SBIR/STTR in fiscal year (FY) 2014. Overall, the SBIR/STTR programs at NIH provided $805.5 million in FY2014, of which $94.4 million was disbursed by the STTR program.

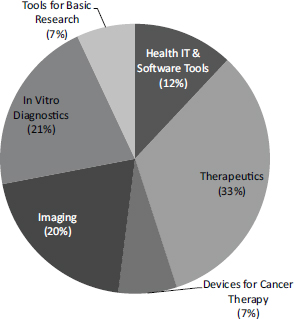

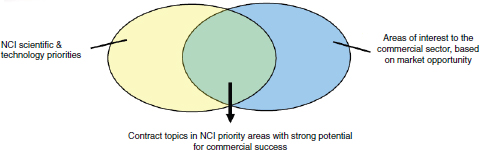

The NIH SBIR/STTR programs support research in a range of areas. A chart from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) illustrates the breadth of the program at that Institute alone, which ranges from short cycle work in health care software and information technology (IT) to the very long cycle of research and development for therapeutic drugs (Figure 2-1).

TABLE 2-1 NIH SBIR/STTR Funding by Program, Phase, and Funding Mechanism, FY2014

| Funding (Millions of Dollars) | |||||||||

| Phase I | Phase II | Fast Track (Phases I and II combined) | Total | Percentage of Total Funding | |||||

| SBIR grants | |||||||||

| competing (new) | 146.1 | 170.4 | 316.5 | 39.3 | |||||

| non-competing (renewals) | 26.0 | 212.5 | 238.5 | 29.6 | |||||

| Fast Track (new) | 17.1 | 17.1 | 2.1 | ||||||

| Fast Track (renewals) | 29.9 | 29.9 | 3.7 | ||||||

| SBIR grants total | 172.1 | 382.9 | 47.0 | 602.0 | 74.7 | ||||

| STTR grants | |||||||||

| competing (new) | 35.8 | 21.7 | 57.5 | 7.1 | |||||

| non-competing (renewals) | 5.6 | 23.9 | 29.5 | 3.7 | |||||

| Fast Track (new) | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.1 | ||||||

| Fast Track (renewals) | 6.3 | 6.3 | 0.8 | ||||||

| STTR total | 41.4 | 45.6 | 7.4 | 94.4 | 11.7 | ||||

| SBIR contracts | 33.2 | 75.9 | 109.1 | 13.5 | |||||

| Total | 246.7 | 504.4 | 54.4 | 805.5 | 100.0 | ||||

| SBIR total | 205.3 | 458.8 | 47 | 711.1 | 88.3 | ||||

| STTR total | 41.4 | 45.6 | 7.4 | 94.4 | 11.7 | ||||

SOURCE: NIH Reporter database, Table 126.

FIGURE 2-1 Funding areas for NCI SBIR/STTR program.

SOURCE: Patti Weber and Andy Kurtz (NCI), “Leveraging NCI SBIR/STTR Opportunities,” webinar presentation, March 6, 2014.

MAJOR FUNDING MECHANISMS

Pathways to Funding

A number of pathways to funding exist within the NIH SBIR/STTR programs. All fall under the general heading of funding opportunity announcements (FOAs). FOAs of all kinds are published weekly in the NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts, which is delivered to subscribers in electronic form.

- Parent announcement. The primary mechanism is the parent announcement from each IC, which is a broad description of IC interests, defined by the agency as an “NIH-wide funding opportunity announcement enabling applicants to submit an electronic investigator-initiated grant application for a specific activity code, e.g., Research Project Grant (Parent R01). Some NIH Institutes or Centers may not participate in all parent announcements.”1

- Omnibus Solicitation. Parent announcements from ICs are aggregated into the Omnibus Solicitation, which includes areas of interest to many of

_______________

1NIH Grants Glossary, http://grants.nih.gov/grants/glossary.htm#P, accessed February 14, 2014.

-

the 24 ICs. The NIH SBIR program publishes one Omnibus Solicitation annually, with three deadline dates for proposal receipt.

- Contract solicitation. NIH publishes one contract solicitation annually, where applicants can seek to meet NIH needs through the contract mechanism, rather than through the more usual grants. (Contracts are discussed separately below.)

- Direct to Phase II solicitation. Topics that will be funded under the direct to Phase II authority are published in a separate direct to Phase II solicitation, which applies to SBIR only.

- Special funding opportunity announcements are periodically issued by one or more ICs and focus on specific areas of science that are priorities of the issuing ICs. Special requirements (e.g., amount of funds that may be requested) may be imposed under these announcements.2 Proposals may also be reviewed directly by the IC rather than through the agency-wide Center for Scientific Review (discussed below).

According to NIH staff, although these various publications provide guidance about NIH priorities, applicants are welcome to apply for funding for projects that are not covered by the various FOAs. This practice lies in contrast with those of the contract research agencies—Department of Defense (DoD) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)—and also with the Department of Energy (DoE) and to a lesser extent the National Science Foundation (NSF), where the topic descriptions in the solicitation are more binding.

These different pathways can utilize different funding mechanisms. Along with the standard SBIR and STTR Phase I, NIH offers the following mechanisms:

- Fast Track. This program allows companies to apply for Phase I and Phase II simultaneously, by providing what is effectively a Phase II application that shows the milestones that would be necessary for both Phase I and Phase II funding. Some of the companies studied for this report applied for and received Fast Track funding but found it to be a difficult pathway suitable only for a small number of proposals. In FY2014, Fast Track accounted for 5.8 percent of total Phase I/Phase II SBIR funding.

- Direct to Phase II. Under the 2011 reauthorization, agencies are permitted to offer companies the opportunity to skip Phase I and apply directly for Phase II funding. This policy innovation emerged in large part in response to requests by NIH, the only agency actively using this mechanism. Data on take-up is discussed in Chapter 3. Direct to Phase II applications must show the equivalent of Phase I results prior to award.

_______________

2NIH Description of the NIH Guide for Grants and Contracts, http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/description.htm#foa, accessed February 14, 2014.

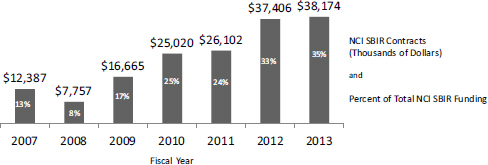

- Contracts. Although a large majority of its SBIR and STTR awards are grants, NIH does provide some contracts as well for SBIR. Contracts are for “direct benefit of the government,” but this benefit is in the form of achieving SBIR goals, not for developing use of technologies at NIH. NIH may be one customer but not the only customer—these are not fee for service contracts. The contracting mechanism is somewhat different from the standard grants mechanism and is discussed in more detail below. NCI has been particularly active in using contracts and provided 35 percent of its SBIR funding through this mechanism in FY2013 (see Figure 2-4).

- Phase IIB. For a number of years, NIH has used the Phase IIB mechanism to address the gap between the end of Phase II funding and the point at which technologies become attractive to private investors by offering additional funding as companies traverse the difficult and expensive regulatory process. These additional awards were originally known as Competing Continuation Awards and are now known as Phase IIB awards. Distinct from NSF’s Phase IIB awards, they offer up to $1 million annually for a period of 3 years and are awarded in addition to Phase II funding.3 Some ICs, notably NCI, offer a separate program that is a variation on Phase IIB that acts similar to Bridge awards to support commercialization at the end of Phase II.

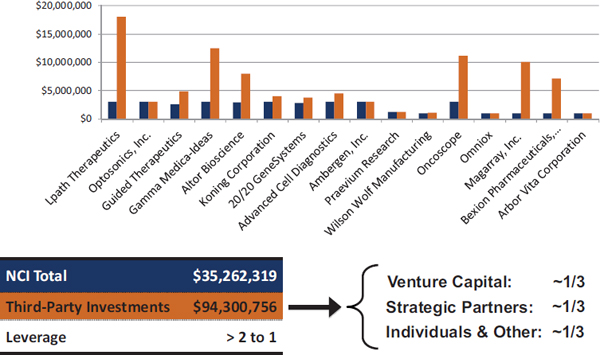

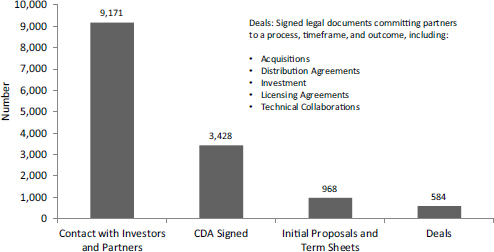

- Bridge awards. Bridge awards also provide awards of up to $1 million annually for up to 3 years. In this case, however, NCI focuses on projects that are particularly ripe for commercialization that address high-priority topic areas for NCI. More importantly, for an application to be “competitive,” NCI expects it to bring in matching funds. As of March 2014, NCI had made 16 Bridge awards totaling more than $35 million, which had attracted matching funds of more than $94 million (Figure 22).4

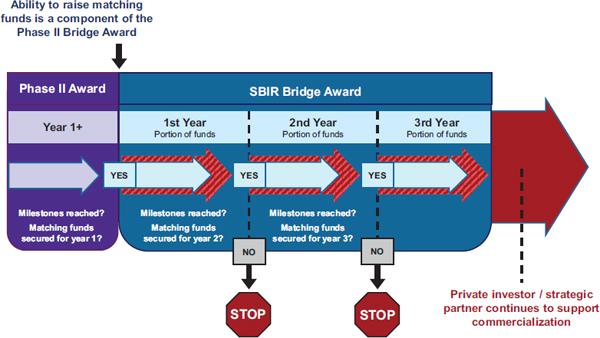

Bridge awards provide milestone-driven funding (see Figure 2-3). Matching funds are not legally mandatory, but NCI has determined that such funding will be required in practice.

The considerable variety of funding mechanisms and pathways at NIH generates a flexible and complex funding landscape, which is further characterized by the varying extent to which the different ICs participate. Not all ICs participate in all of these mechanisms, and those that do, do so to varying and changeable degrees.

_______________

3This is not consistent across ICs. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute offers $3 million over 3 years, but doesn’t stipulate the annual amount.

4Patti Weber and Andy Kurtz (NCI), “Leveraging NCI SBIR/STTR Opportunities,” webinar presentation, March 6, 2014.

FIGURE 2-2 Bridge awards at NCI.

SOURCE: Patti Weber and Andy Kurtz (NCI), “Leveraging NCI SBIR/STTR Opportunities,” webinar presentation, March 6, 2014.

FIGURE 2-3 Milestone-driven funding through Bridge awards.

SOURCE: Patti Weber and Andy Kurtz (NCI), “Leveraging NCI SBIR/STTR Opportunities,” webinar presentation, March 6, 2014.

Contract Funding

The contract solicitation for NIH and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is published once annually. It is governed by Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) and is designed to address targeted milestone-driven topics. For the FY2014 solicitation, for which proposals were due November 5, questions about the solicitation had to be formally submitted by September 19. The period between these dates constitutes a quiet period during which the agency is limited in how it may respond to questions posed by potential applicants.

Contract funding continues to expand at NIH, particularly at some ICs. At the forefront of this expansion, NCI utilizes contracts for more than one-third of its NCI SBIR funding (see Figure 2-4). Discussions with NCI staff indicate that NCI appears focused on contracts because this mechanism leaves control of selection entirely with the IC (the Center for Scientific Review is not involved in study sections) and because it offers tighter control of the project itself, where payments are linked to milestones not just time and materials.

There are a number of key differences between grants and contracts at NIH. Contract opportunities are more narrowly defined and are usually not open to investigator-initiated ideas. Potential applicants are required to discuss their proposals with the contracting officers. Contracts can be funded through specific amounts set aside by the IC for particular topic areas, unlike grants, which in principle are funded from the same pot. Reporting requirements also differ; in general, contracts require more extensive program staff involvement.

The selection process and criteria are also different for grants and contracts. Contract applications are reviewed directly at the IC, at the separate Center for Scientific Review (CSR) which governs most grant applications. The review process is also more focused as special review panels are formed for each topic rather than the more general panels at CSR which consider clusters of related topics. The basis for a contract includes additional criteria: the specific negotiated deliverables and the proposed budget. These differences are summarized in Table 2-2.

FIGURE 2-4 Contracts funding at NCI.

SOURCE: NCI Contracts webinar, September 14, 2014, http://sbir.cancer.gov/objects/pdfs/2014-09-18_nih-sbir-contracts-webinar.pdf, accessed February 16, 2015.

TABLE 2-2 Differences Between Contracts and Grants

| SBIR Grants | SBIR Contracts | |

| Scope of the proposal | Investigator-defined within the mission of NIH | Defined (narrowly) by the NIH |

| Questions during solicitation period? | May speak with any Program Officer | MUST contact the contracting officer (see solicitation) |

| Receipt dates | 3 times/year for Omnibus | Only once per year |

| Reporting | One final report (Phase I); Annual reports (Phase II) | Kickoff presentation, quarterly progress reports, final report, commercialization plan |

| Set-aside funds for particular areas? | No | Yes |

| Program staff involvement | Low | High |

| Peer review locus | NIH Center for Scientific Review (CSR) | At each IC |

| Review sections Basis for award | Sections review applications for different programs in similar topic areas Peer review score Program assessment | Specific sections for each single topic Peer review score Program relevance and balance Negotiation of technical deliverables Budget |

SOURCE: NCI Contracts webinar, September 14, 2014, http://sbir.cancer.gov/objects/pdfs/2014-0918_nih-sbir-contracts-webinar.pdf, accessed February 16, 2015.

NCI in particular uses contracts to focus funding on specific areas where it sees considerable commercial potential (see Figure 2-5). Contracts allow NCI to control the flow of funding more directly by topic.

The timeline for contracts is also quite tight. For example, companies whose proposals are rejected can receive a formal debrief if requested within 3 business days of the announcement.

It could be said that this use of contracts is an effort to turn the NCI SBIR program from a traditional science-based research program into a portfolio-oriented investment program analogous to, though in many ways different from, those run by venture capital investors. This approach is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3 (Program Initiatives at NIH).

FIGURE 2-5 NCI strategy for contracts.

SOURCE: “NCI Presentation to 16th Annual NIH SBIR/STTR Conference,” October 21-23, 2014, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

TOPIC DEVELOPMENT

The topics published in the Omnibus Solicitation and in the more specialized Program Announcements are developed within each of the ICs, and that process can vary by IC. In general, topics are suggested by program managers who are specialists in specific research areas within the IC, and are then vetted, edited, and eventually approved for publication via internal review mechanisms that differ by IC. The IC Director eventually signs off on the IC’s SBIR/STTR topics, although most often as a formality. Because NIH does not limit applications to topics identified in solicitations (except for contracts), the topic selection process itself is not the gating procedure it is for other agencies. Therefore, topic selection is important, but not nearly as important as at DoD or NASA.

Program Flexibility

The NIH SBIR/STTR programs are uniquely flexible and can adapt to meet the needs of applicants in ways that more rigid programs cannot. On most dimensions, they are the most flexible of all the SBIR/STTR programs.

- Focus on investigator-initiated research. NIH makes clear that topics listed in the Omnibus Solicitation are guides, not boundaries, for applicants: “SBIR grant applications will also be accepted and considered in any area within the mission of the Components of Participating Organizations listed for this FOA.”5 Although targeted solicitations have become more common and contracts a more important mechanism (contracts are more tightly specified), research conducted under SBIR/STTR at NIH is still largely investigator driven.

_______________

5PHS 2014-02 Omnibus Solicitation of the NIH, CDC, FDA and ACF for Small Business Innovation Research Grant Applications (Parent SBIR [R43/R44]).

- Multiple funding opportunities and announcements. Although NIH publishes its Omnibus Solicitation only once annually, numerous other funding opportunities emerge over the course of the year. A solicitation for NIH contracts is published annually, and ICs and clusters of ICs publish targeted funding announcements throughout the year.

- Multiple applications dates. Although there is only one solicitation, NIH offers three submission dates annually, which provides investigators with a reduced timeline to funding compared to an annual deadline. This is especially helpful for small companies.

-

Provision of funding flexibility. NIH funding for SBIR/STTR provides several flexible elements.

- Funding amounts. Amounts are not pre-set, and selection panels do not compare funding requests between applications. NIH has consistently provided funding in response to applications that goes beyond Small Business Administration (SBA) guidelines (with appropriate SBA waivers). See more on extra-large awards in Chapter 3.

- Supplementary funding. NIH provides small amounts of supplementary funding in cases where the research plans can be completed with a minor increase in support.

- No-cost extensions. NIH will normally extend the timeline for an award, sometimes substantially. A single, 12-month, no-cost extension is automatically approved for grants and can be managed directly by the awardee through the NIH electronic grants management system.6

- Multiple support mechanisms. The introduction of Phase IIB and Direct to Phase II indicates that NIH continues to seek ways to match available funding with the needs of companies and investigators.

- Resubmission of applications. The ability to resubmit applications after addressing flaws identified by selection panels is a unique feature of the NIH SBIR/STTR programs and is highly commendable.7

Overall, the flexibility of the NIH SBIR/STTR programs is a strongly positive characteristic, and other agencies should examine how they might—within their own organizations and cultures—adapt some of the mechanisms developed by NIH.

_______________

6NIH, Electronic Records Administration, https://era.nih.gov/services_for_applicants/reports_and_closeout/no-cost_extension.cfm, accessed July 16, 2015.

7NIH, NIH Policy on Resubmission of Grant Applications, http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/amendedapps.htm, accessed July 16, 2015.

AWARD SELECTION

Award selection procedures are different for grants and contracts and are discussed separately below. Grants continue to predominate, although the numbers of and funding for contracts have expanded sharply in recent years.

Grant selection at NIH is a five-step process:

- Administrative review

- Peer review

- Program officer prioritization

- Advisory Council review

- Director approval

Administrative Review and Assignment to Study Section

All incoming grant applications are reviewed by the CSR to ensure that all of the necessary material is provided and all of the requirements described in the solicitation are met. According to CSR staff, CSR reviews 70-80 percent of SBIR/STTR applications, with the remainder reviewed by the IC.

Applications that pass administrative review are then assigned to a Scientific Review Group (SRG) served by a scientific review officer (SRO). The SRO manages the peer-review process for a particular technical area and usually handles two to three selection panels per funding round.

A primary SRO responsibility is to recruit academic and other experts to participate on review panels (in an unpaid capacity). Each panel is expected to handle approximately 100 applications for each funding round, during the course of one or two (sometimes three) meetings. Given the number of panels in operation at any given time, recruiting panelists remains a challenging assignment for SROs. Panelists are expected to work on 8-10 applications per round. Over time, the CSR has developed specialized panels to handle SBIR/STTR applications, with a goal that each will include one or more representatives with commercial experience.

Panel organization and expertise vary by review group. Of the five broad divisions, two have a single Integrated Review Group (IRG8) that handles all SBIR/STTR applications for that area. Each of the remaining three divisions has an SBIR/STTR panel. Panels tend to be supported by the same SRO for a number of years.

_______________

8For details on IRGs, see NIH Integrated Review Groups, http://public.csr.nih.gov/StudySections/IntegratedReviewGroups/Pages/default.aspx, accessed August 9, 2015.

Ease of Application

The 2014 Survey sought to probe more deeply into the process of application and award management. One question concerned the degree of difficulty involved in applying for a Phase II award compared with applications to other federal programs.

Overall, about 20 percent of respondents reported that the Phase II application process was easier or much easier than the application process for other sources of federal funding, while 13 percent of respondents indicated that it was more difficult or much more difficult (see Table 2-3).

The Peer Review Process9

Peer review is a primary cornerstone of NIH grant disbursement. Through this process, applications are reviewed by a group of technical experts from outside NIH, who provide numerical scores for each application. NIH peer-review criteria are mandated by federal regulations and can be summarized as follows:10

- Project Significance, focused on new knowledge and techniques, and new applications.

- Principal Investigator qualifications and expertise.

- Innovation, defined as “novel theoretical concepts, approaches or methodologies, instrumentation, or interventions.”

- Effectiveness of the approach, showing that researchers understand and have addressed key problems and risks.

- Research environment, including access to adequate institutional support, equipment, and other physical resources.

Notably, commercial potential or even proposed distribution or dissemination of new technologies does not appear explicitly on this list or on the supplementary list of additional criteria that may be applied, though it may be seen as being subsumed under “project significance.”

Overall, the peer reviewers’ responsibilities constitute an extensive remit, covering activity before, during, and after the study panel meeting.11 SROs do not

_______________

9The general information in this section is drawn from the NIH Peer Review Process webpage, http://grants2.nih.gov/grants/peer_review_process.htm#Initial. More specialized information about SBIR/STTR review is drawn from discussion with agency staff. The NIH peer-review system itself is mandated by statute under section 492 of the Public Health Service Act and Federal regulations governing “Scientific Peer Review of Research Grant Applications and Research and Development Contract Projects” (42 CFR Part 52h).

10National Institutes of Health, “Peer Review Process,” http://grants2.nih.gov/grants/peer_review_process.htm#Initial, accessed May 13, 2014.

11See NIH Role of the SRO—A Quick Guide for a more extensive overview, http://public.csr.nih.gov/ReviewerResources/MeetingOverview/Pages/ROLE-OF-THE-SRO----A-QUICK-OVERVIEW.aspx, accessed March 31, 2015.

TABLE 2-3 Ease of Application for SBIR/STTR Phase II Awards at NIH

| Percentage of Respondents | ||||

| NIH Total | SBIR Awardees | STTR Awardees | Phase IIB Awardees | |

| Much easier than applying for other federal awards | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.2 | |

| Easier | 17.8 | 17.2 | 21.1 | 22.2 |

| Easier or much easier | 20.6 | 20.1 | 23.3 | 22.2 |

| About the same | 42.9 | 41.2 | 52.2 | 37 |

| More difficult | 9.1 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 7.4 |

| Much more difficult | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.3 | |

| More or much more difficult | 12.6 | 12.6 | 12.2 | 7.4 |

| Not sure, not applicable, or not familiar with other federal awards or funding | 23.9 | 26.1 | 12.2 | 33.3 |

| BASE: TOTAL RESPONDENTS ANSWERING QUESTIONa | 573 | 483 | 90 | 27 |

a Due to a high percentage of the population that could not be reached, and a low response rate from those who were reached, the number of respondents is relatively small.

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 53.

have any direct input into selection: their role is to manage the peer-review process. The program officer may or may not be present during the review panel meeting.

Traditionally, application reviews have been led by a primary reviewer and include a secondary reviewer and a third or monitoring reviewer. Although NIH has not provided data on the composition of study sections (as review panels are known at NIH), discussions for case studies and numerous comments from survey respondents indicate that these panels are largely dominated by academic scientists. More recently, in an effort to improve commercialization review, the CSR has issued guidelines asking SROs to ensure a larger percentage of panelists with commercialization expertise.

Peer-Review Outcomes

Selection Criteria

NIH publishes selection criteria for SBIR/STTR awards. They are listed below and described in more detailed in Box 2-1:

- Significance of the project

- Principal investigator (PI) qualifications

BOX 2-1

NIH SBIR/STTR Selection Criteria

Scored Review Criteria

Reviewers will consider each of the review criteria below in the determination of scientific merit and give a separate score for each. An application does not need to be strong in all categories to be judged likely to have major scientific impact. For example, a project that by its nature is not innovative may be essential to advance a field.

Significance

Does the project address an important problem or a critical barrier to progress in the field? If the aims of the project are achieved, how will scientific knowledge, technical capability, and/or clinical practice be improved? How will successful completion of the aims change the concepts, methods, technologies, treatments, services, or preventive interventions that drive this field? Does the proposed project have commercial potential to lead to a marketable product, process, or service? (In the case of Phase II, Fast-Track, and Phase II Competing Renewals, does the Commercialization Plan demonstrate a high probability of commercialization?)

Investigator(s)

Are the PD(s)/PI(s), collaborators, and other researchers well suited to the project? If Early Stage Investigators or New Investigators, or in the early stages of independent careers, do they have appropriate experience and training? If established, have they demonstrated an ongoing record of accomplishments that have advanced their field(s)? If the project is collaborative or multi-PD/PI, do the investigators have complementary and integrated expertise; are their leadership approach, governance, and organizational structure appropriate for the project?

Innovation

Does the application challenge and seek to shift current research or clinical practice paradigms by utilizing novel theoretical concepts, approaches or methodologies, instrumentation, or interventions? Are the concepts, approaches or methodologies, instrumentation, or interventions novel to one field of research or novel in a broad sense? Is a refinement, improvement, or new application of theoretical concepts, approaches or methodologies, instrumentation, or interventions proposed?

Approach

Are the overall strategy, methodology, and analyses well-reasoned and appropriate to accomplish the specific aims of the project? Are potential problems, alternative strategies, and benchmarks for success presented? If the project is in the early stages of development, will the strategy establish feasibility and will particularly risky aspects be managed?

If the project involves human subjects and/or NIH-defined clinical research, are the plans to address 1) the protection of human subjects from research risks and 2) inclusion (or exclusion) of individuals on the basis of sex/gender, race, and

ethnicity, as well as the inclusion or exclusion of children, justified in terms of the scientific goals and research strategy proposed?

Environment

Will the scientific environment in which the work will be done contribute to the probability of success? Are the institutional support, equipment, and other physical resources available to the investigators adequate for the project proposed? Will the project benefit from unique features of the scientific environment, subject populations, or collaborative arrangement?

SOURCE: NIH Grants Guide Section V, http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-14-088.html#_Section_V._Application, accessed September 29, 2015.

- Innovation

- Approach (does the technical approach seem appropriate)

- Environment (focused on the facilities in which the work will be done)

Study sections divide up review responsibilities. As noted above, most applications will have a primary reviewer, secondary reviewer, and third or monitoring reviewer. Discussions with agency staff and researchers with experience on study sections indicate that the primary reviewer’s views carry considerable weight in most cases. The reviewers provide a written review that scores each application against each of the criteria on a 1-9 scale with 1 being the best and 9 the worst. The reviewers also provide a preliminary single impact score for the application. These scores are used to determine which applications will be discussed at the meeting (not all applications are discussed). Significantly different scores among assigned reviewers will likely be discussed in the study section.

At the meeting, after discussion, each committee member provides an overall impact score for the application. The average of all committee scores, including those from assigned reviewers, is then averaged and multiplied by 10 to provide a score ranging from 10 (maximum) to 90 (minimum).

Commercialization potential and capabilities are not among the formal criteria for selection. They are therefore not reflected in the criterion scores, although they can be (and, in the case of SBIR/STTR, should be) a factor in the overall impact score for a proposal.

An appeals process is outlined on the NIH website, but company executives indicated during case study discussions that they consider appeals to be of little use and prefer to resubmit an application for subsequent review (see below).

Conflicts of Interest

Scientific review offices are assigned responsibility for managing conflicts of interest. Panel members are required to disclose any known conflicts and to recuse themselves from consideration of related proposals. In general, discussions with company participants and responses from the 2014 Survey did not indicate that conflict of interest is a widespread problem.

Nonetheless, academics working in technical areas that are very close to those of an applicant can have an intellectual conflict of interest. Even if no direct financial interest is at stake, researchers may still be concerned that the company’s work overlaps and hence competes with their own. Instructions to panelists do not describe this kind of conflict of interest and the need for academic reviewers to recuse themselves as necessary.

There is also a tension between ensuring that panels contain members with experience in the commercialization of technology—which often means experience in private-sector companies that are working in closely aligned technical areas—and ensuring that there are no commercial conflicts of interest. Several case study respondents noted that they paid careful attention to the composition of study sections; some tried to ensure that their proposals were assigned to the “right” study section, and others sought the recusal of specific panel members when needed.

Study sections must therefore tread a narrow line: they must ensure that appropriate scientific expertise and commercial understanding are available for an effective review, and at the same time, they must try to ensure that conflicts of interest are eliminated for a fair review. In general, this assessment did not reveal systematic problems in this area, but it did reveal the existence of concerns among small business.

Lack of Sufficient Commercial Expertise

Several of the company executives who took part in case study discussions indicated that selection panels lacked commercialization experts and that most were heavily weighted toward research scientists. Many survey respondents expressed similar views (see Box 2-2). A CSR staff member working on SBIR/STTR said that no rules exist about including panelists with commercial expertise, although 20-50 percent representation by commercialization experts is recommended. However, company executives who had served on selection panels suggested that it was not uncommon for panels to include only one or two such reviewers.

Company executives also observed that what counted as commercialization expertise was often unclear; scientists from the private sector are assumed to have commercialization expertise, even though most industry scientists’ work is heavily focused on science rather than commercialization.

CSR staff confirmed that CSR does not track the extent to which SROs follow the guidelines noted above. There are no data on the availability of commer-

BOX 2-2

2014 Survey Respondent Recommendations for Improved Review (Representative Comments)

Need more company reviewers on SBIR panels. Need less academic reviewers.

Enhance expertise of review panels in order to better align review with objectives of SBIR/STTR program.

Often review panels do not understand the FDA [U.S. Food and Drug Administration] process and difficulties getting clearance or approval from the FDA . . . review panel members should be educated on the purpose of Phase IIBs before the review panel and proposal reviews take place.

CSR and program need to step up hugely, as they have even less of a clue about the FDA regulatory process than the entrepreneur. Yet, they make funding decisions with little or no knowledge of what needs to be done.

[We recommend] an easier way to assess the appropriateness of each review group to your application to get the best match, and improved education of peer reviewers in academia who review R43s and R44s like R01s.

Give proposal reviewer fewer proposals to review so they can do a better job. Insist that reviewers who do not understand what is proposed recuse themselves from being one of the three primary reviewers.

Instruct reviewers to act professionally, and not to be biased in favor of typical academic biases (number of “good” publications). I have sat in review panels where participants exclaim their pride that none of their research will ever be marketable. Additionally, there is built-in bias against collaboration with foreigners, even when all the research occurs in the USA.

Integrate greater support for products with real market potential into the peer review process. For educational products, review panels tend to focus on products that will have low market potential.

Offering additional funding opportunities that are reviewed by non-academic based reviewers. It would great to have reviewers with experience in getting a biotech device to market.

Make sure all review panels know the specific requirements from the FDA that are needed and provide a clear path to ensure communication.

Provide funding for FDA related consultants independent of the SBIR funds through a mechanism that does not involve the study section. Most SBIR study sections are made up of academic investigators with little to no understanding [of] the FDA or the commercialization process. SBIR grants are handled as if they were R01 or R21 proposals.

Provide review process that allows for best assessment of the product for commercialization. Reviewers with appropriate backgrounds would be helpful.

. . . [The] majority of the reviewers for SBIR/STTR are professors, who have no commercialization backgrounds or experiences . . . reviewer committee should add some reviewers with more marketing and product development background.

Stop demanding a randomized control trial in Phase I. Allow for a more commercially viable development process in Phase I so a minimum viable product is evaluated for market acceptance not just effectiveness of intervention.

The NIH review process for SBIR/STTR has become more and more frustrating to all device companies. The funding repeatedly rewards proposals including complex biochemical research devoted to a new test or therapy that will be of little direct benefit to patients.

The reviewers of our Phase IIB were TOTALLY unaware that the company proposing had written the Phase IIB following FDA guidelines as to what we had to complete for clearance.

SOURCE: 2014 Survey.

cialization expertise to selection panels, and a review of commercial potential can be provided by any panelist, either in the scoring or in the course of discussion.

At a minimum, NIH does not track or manage panels to ensure that sufficient commercial expertise is available to help guide deliberations.

Resubmission

As a unique feature of the NIH SBIR/STTR programs, applicants are permitted to resubmit their applications during the 37 months following the initial rejection.12 This gives applicants the opportunity to address weaknesses identified during the first review and to strengthen their proposals. In recent years, about one-third of all funded Phase I grants have utilized the resubmission process, according to the NIH SBIR/STTR Program Office. According to NIH, “Resubmissions normally are not permitted for applications received in response to a Request for Applications (RFA) unless it is specified in the FOA, in which case only one resubmission will be permitted.”13

Meetings with applicants (see case studies) indicate that while considerable unhappiness with the peer-review process in general remains, the existence of the resubmission mechanism acts as an important safety valve for the programs. Resubmission is seen as a very valuable aspect of the programs.

Although resubmission offers an important route for improved applications, the process itself does not work as well as possible from the company’s perspective. Most notably, the applicant receives the debrief from the NIH review process too late to resubmit by the next deadline. As a result, resubmission currently

_______________

12NIH Policy on Resubmission, http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/amendedapps.htm, accessed June 16, 2015.

13Ibid.

imposes an 8-month delay, which is challenging for smaller companies without other revenue sources. Aware of this issue, the NIH SBIR/STTR Program Office is considering changes to the review process so that debriefs can be provided to companies in time for them to resubmit by the next deadline.

An Agency Perspective

The difficulties facing small business concerns in the NIH review process have been acknowledged by some NIH staff: namely, that the NIH review process is not well designed to ensure that commercial plans submitted as part of the application process—especially for Phase II—are reviewed by panelists with expertise in the commercialization of biomedical technologies in general and the specific technologies at hand in particular.

Program Officer Prioritization

Upon receipt of the scores from the review panel, the IC program officer creates a priority list based on the scores, ranking each proposal within the officer’s technical area relative to others. The program officer then runs these scores against the available budget to create the draft pay line (proposals scoring below this line are to be funded—given that lower scores are better in the NIH system).

The draft pay line is subject to review and adjustment by the program officer, who accounts for issues such as budgets and agency priorities. For example, it may be that the IC is already funding a similar technology, in which case the program officer may decide that the funds would be better spent elsewhere. The program officer may also determine that, although of high quality, the proposal will cost too much to be worth the IC’s investment. (It is only at this point that the relative budgets for proposals are compared and become a factor. Study sections do not compare budgets.) The program officer may also decide that a proposal scoring below the pay line is nonetheless of strategic importance to the IC and should be funded anyway. In addition, the program officer may decide that the review of a proposal was in some way done incorrectly and that a different (and perhaps fundable) score should have been given.

Different ICs have different cultures and different rules. Some give their program officers a considerable degree of freedom to make funding decisions that conflict with the initial ranking from the study sections. Others see this as an exception and expect most rankings to be respected. NIH does not retain aggregate data about the extent to which program officers change funding decisions. However, discussions with agency staff suggest that such changes occur in no more than 10 percent of proposals, and for most ICs, no more than 5 percent.

Advisory Council Review and IC Director Approval

NIH provides an additional layer of review, focused on what program officers see as special cases.

The Advisory Council deals with all of the funding provided by the IC, in which SBIR is only a small fraction. The Advisory Council discusses much larger funding decisions, and therefore can feasibly address only a small number of SBIR cases. According to agency staff, these cases tend to fall into two areas: (1) the program officer is overriding the original ranking list and seeks confirmation that his or her judgment is appropriate and (2) the amount of funding is especially large. Thus discussion in the Advisory Council is unusual for an award the size of an SBIR/STTR award.

The final step in the approval process is approval by the IC director. Once again, different ICs have different procedures for this last step, but the small size of SBIR awards makes it unlikely that any single proposal will attract substantial senior management time and concern. In most cases director approval is a formality.

Checks and Balances Within the Review Process

A common concern raised by case study and 2014 Survey respondents centered on the reviewers. Companies reported cases in which reviewers did not understand the technology, the business, the market, or NIH interest in a technology despite its publication as a topic.

Given the number of applications and the difficulties in finding competent and experienced reviewers to sit on panels, it is not surprising that applicants complain about unwarranted or illegitimate criticism from reviewers. This is not a problem unique to NIH, but the nature of the review process at NIH seems to generate more cases.

NIH is well aware of these issues, not only for SBIR/STTR grants but also for all NIH grants. However, the problem may be exacerbated within the SBIR/STTR programs because of the need for commercial review, which most academic scientists are not competent to provide. NIH has taken a number of steps to provide checks and balances.

- Three lead reviewers. The assignment of three lead reviewers to a proposal is in and of itself an effort to provide checks and balances. Still, in most cases there will be a primary reviewer who carries the most weight.

- The role of the scientific review officer (SRO). Although SROs do not participate in the discussion and have no hand in the final recommendation and feedback to the company, they are responsible for ensuring that potential conflicts of interest are addressed and also in a larger sense that the process is fair. However, it is not clear whether SROs usually take

-

action in cases where they believe the proposal may not have received an appropriate review.

- The role of the program officer. Although driving the funding decision, the reviewer scoring is not determinative. Program officers can reach beyond the pay line to fund a project that they consider to be of special merit and equally can decide not to fund a project that is within the pay line but that they believe does not meet the IC priorities. In general, this process works more to align scores with IC priorities than to deal with problematic reviewer scoring.

- Resubmission. Unique among SBIR funding agencies, NIH permits resubmission and reconsideration of unfunded proposals against subsequent deadlines. If a company believes that its proposal did not receive a fair review, then it can make adjustments and resubmit. This is an important mechanism for improving the overall quality of both proposals and the overall process, and it is recognized as such by applicants and NIH staff. However, this process involves significant costs: there is no guarantee that the proposal will be funded; it may go to a different study section or study section with different personnel who have different concerns; and it imposes significant costs on the small business. Moreover, prior to 2015, feedback arrived too late for companies to submit during the next cycle, so resubmission in effect imposed an 8-month wait. For small businesses, such a delay can be very challenging. NIH is now working to provide companies with feedback from selection panels in time for them to resubmit at the next SBIR deadline, but this issue has not yet been fully addressed.

Almost all of the company executives who engaged in case study discussions have served on selection panels and thus fully understand their operations as well as their strengths and weaknesses. Few of them thought that the current system should be replaced by systems similar to those of other agencies, where small groups of agency staff drive the selection process. However, many were interested in finding better ways to address weaknesses in the system. In particular, many suggested that NIH allow companies to rebut or address criticism in the course of review, rather than through the resubmission process. NIH staff hold that rebuttal would impose significant delays and costs on the review process and that improving and streamlining resubmission was perhaps a more effective approach.

Excluding Poor-Quality Proposals

Most proposals to the NIH SBIR/STTR programs fail. Success rates for Phase I are usually well below 20 percent, depending on the number of applications submitted and the amount of funding available. NIH undertakes a triage within the study section, providing a score only for the top 50 percent of proposals.

It is apparent that reducing the number of poor-quality proposals would be of immediate benefit to NIH, because reviewers could focus on better proposals and because conceivably there could be fewer study sections. Fewer failing proposals would also benefit the applicants.

However, NIH does not use some of the methods employed at other agencies to reduce the number of poor-quality proposals. For example,

- NSF limits the number of applications to two annually per firm, ensuring that firms focus on their most promising projects.

- DoE requires a white paper before application and provides applicants with rapid feedback to help inform decisions as to whether or not to apply. NSF also uses a white paper process, although its approach is somewhat less rigorous. Neither process prevents a company from applying even if advised that its application is unlikely to succeed.

Perhaps in part because the number of applications to NIH has been falling for some time (see Chapter 4, SBIR and STTR Awards at NIH), the NIH SBIR program has historically had little interest in limiting applications to make the application process more efficient.

FUNDING GAPS AND AWARD TIMELINES

The 2014 Survey asked respondents about funding gaps. Case studies as well as prior reports by the Academies14 have noted that funding gaps are particularly difficult for small businesses that have few other resources. Projects can be badly damaged by funding gaps that may require staff to be reassigned or even let go, and delays can be crippling in areas where technology is advancing rapidly.

The 2014 Survey provides some insights into the impact and effects of funding gaps between Phase I and Phase II. Sixty-eight percent of respondents indicated that they had experienced a gap between the end of Phase I and the start of Phase II for the surveyed award.15 This is down since the 2005 Survey, which reported 80 percent of respondents for SBIR only, compared with 69 percent (for SBIR only) for the 2014 survey.16

This gap can have a range of consequences for the company. Table 2-4 indicates the kinds of impact on respondents who had experienced a funding gap. Thirty-one percent of respondents reported that they stopped work altogether

_______________

14Effective July 1, 2015, the institution is called the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. References in this report to the National Research Council or NRC are used in an historic context identifying programs prior to July 1.

152014 Survey, Question 22.

16National Research Council 2009 op. cit. p. 258. STTR recipients were not included in the 2005 Survey.

TABLE 2-4 Effects of Funding Gaps Between Phase I and Phase II

| Percentage of Respondents | ||||

| NIH Total | SBIR Awardees | STTR Awardees | PHASE IIB Awardees | |

| Stopped work on this project during funding gap | 31.2 | 34.1 | 14.8 | 5.3 |

| Continued work at reduced pace during funding gap | 57.1 | 54.4 | 72.1 | 68.4 |

| Continued work at pace equal to or greater than Phase I pace during funding gap | 9.3 | 9.2 | 9.8 | 26.3 |

| Company ceased all operations during funding gap | 0.5 | 0.6 | ||

| Other (specify) | 2.2 | 2.3 | 1.6 | |

| Received gap funding between Phase I and Phase II | 6.1 | 5.7 | 8.2 | 5.3 |

| BASE: EXPERIENCED A FUNDING GAP BETWEEN PHASE I AND IIa | 410 | 349 | 61 | 19 |

aDue to a high percentage of the population that could not be reached, and a low response rate from those who were reached, the number of respondents is relatively small.

NOTE: Numbers do not sum to 100 percent because multiple responses were permitted.

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 23.

during this period, while 57 percent worked at a reduced level of effort. About 1 percent ceased operations.

Aside from the direct impact of delayed projects, funding gaps can have long-term consequences, especially for smaller companies, where in some cases there is insufficient work to retain key project staff during the gap period. Many of the comments received from the 2014 Survey reflected the negative impact of funding gaps (see Box 2-3). Suggestions from survey and case study respondents fall into three main categories:

- Create or expand a gap funding mechanism between Phase I and II. Currently NIH relies on “work at your own risk” as the sole mechanism. In this case, a company can continue to work at its own risk. If the project eventually receives a Phase II award, then the company can be repaid for the resources expended during this period.

- Reduce the time between Phases, in part by making decisions more quickly, creating conditions that allow immediate resubmission in the next cycle.

BOX 2-3

2014 Survey Responses Related to Funding Gaps Between Phase I and Phase II (Representative Comments)

Bridge funding between Phase I and II SBIR should be much easier.

Reduce gap in funding between Phase I and Phase II. Recent “direct to Phase II” awards are a good step forward.

The SBIR program rocks—[but] the gap between phase 1 to 2 is terrible—it kills projects in startup companies.

Improved access to gap funding and/or ways to reduce the gap between Phases 1 and 2. Since the odds of winning a fast-track NIH grant are close to zero.

One of the biggest problems we face is the gap between phase 1 and phase II.

The funding gap between Phase I and II is difficult. Some thought needs to be given to gap funding.

Address the gap between Phase I and Phase II. Create review cycles that allow for earlier re-submit of un-funded grant applications.

Opportunities for gap funding (with suitable milestones met) would help to retain valuable/trained staff used on the Phase I and would help to assure a smooth transition to Phase II

Reducing the gap time between Phase I and Phase II would be most helpful, or providing some Phase I to Phase II interim funding

Shorter time between phase I and phase II would be helpful. Perhaps a program review of quantifiable phase I milestones would allow phase II funding to start without going to traditional study section. This would expedite the commercialization process.

SOURCE: 2014 Survey.

- Enhance access to Fast Track and/or direct to Phase II. Some survey respondents noted that Fast Track is difficult to access, which could be improved with better guidance to study sections.

NIH has tried to address potential funding gaps between Phase I and Phase II in three ways. Most notably, NIH offers a “work at own risk” approach. This approach cannot be used for contracts because of FAR, but it provides grant recipients with an important way to continue work on projects during the gap before Phase II funding. Of course, companies that do not eventually receive Phase II funding will incur costs but receive no repayment.

NIH has also tried to reduce the actual time between the end of Phase I and the beginning of Phase II. The gap is reported to SBA in the agency’s annual report. However, because NIH offers three funding opportunities per year and in particular because the agency allows resubmission, the gap data are not especially useful and are not comparable to those of other agencies. Agency staff are work-

ing to accelerate delivery of debriefs, an initiative which would allow companies to resubmit more rapidly.

The gap can also be eliminated through either Fast Track—which provides for smooth transition to Phase II without recourse to a study section review—and direct to Phase II—a new program permitted under reauthorization. In FY2014, Fast Track accounted for 71 of the 730 Phase I + Fast Track awards; the success rate for Fast Track applications was 19 percent, compared to 16 percent for Phase I SBIR applications.17

More generally, survey and case study respondents expressed concerns about the length of time between initial application and eventual Phase II funding. Box 2-4 presents some of their concerns.

Both the NIH Program Office and SBA are working to monitor the pace of awards and to reduce unnecessary delays. However, SBA focuses only on aggregated data, which are of little use in pin-pointing problems. In addition, because awards are made by individual ICs it is not clear whether the Program Office has either access to data or sufficient influence to lead change in this area. NIH has not provided information that reflects an understanding of best practices among the ICs in this regard.

CLINICAL TRIALS AND SBIR/STTR

Unlike at most other SBIR/STTR agencies, many NIH awardees must comply with a potentially expensive and time-consuming regulatory process before they can market new products. This section addresses that process.

The Changing Role of Large Pharmaceutical Companies and Venture Capital Firms

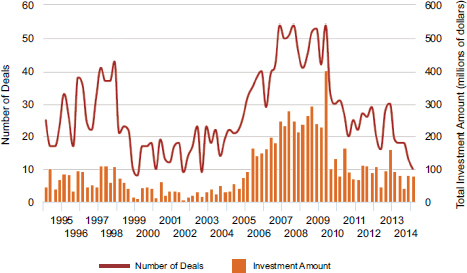

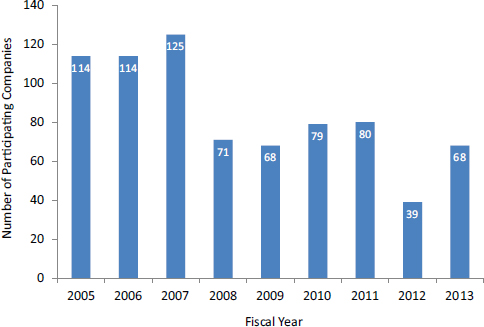

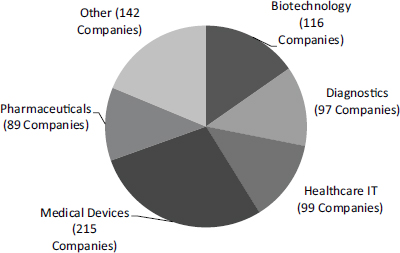

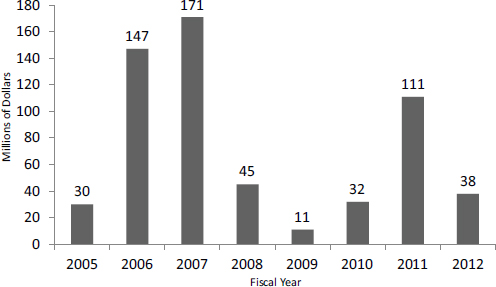

Starting around 2004, venture capital firms supplied a considerable amount of the financial fuel for biomedical startups and early-stage companies, while large pharmaceutical companies have waited to see the results of early clinical trials before considering investments. However, that support declined sharply after the financial crash of 2008, and the retreat of venture capital (VC) funding from seed stage in investments is by now quite well known. Figure 2-6 shows data for the biotechnology and medical device sectors for seed-stage funding from the PwC/NVCA Moneytree™ Report based on data from Thomson Reuters.

The retreat of venture capital firms means that small innovative companies must find other sources of funding for clinical trials. There is conflicting evidence about the role of large pharmaceutical companies, which use the work of smaller companies as a pipeline for their own later development of new drugs and therapies. On the one hand, companies report that partnering with large pharmaceutical

_______________

17NIH Annual Funding Report, SBIR grants, Table 127.

BOX 2-4

2014 Survey Respondent Concerns About the Lengthy Timeline for NIH SBIR/STTR Awards (Representative Comments)

Reduce delay between application and award decision and actual award (can stretch to 12 months or longer). Reduce administrative delays for non-competitive renewals (delays of several months are often encountered).a Reduced delays in F&A negotiation. We experienced 12+ month delays in processing proposals.

Reduce time between application and award decision. This has taken more than 12 months in our case. Reduce administrative delays in funding release each year during phase II. This has taken greater than 4 months in our case. That is we have at times experienced a four month delay between years of Phase II.

Overall, the process of submission, review, & funding was fair, but agonizingly slow. One must start the Phase 2 proposal process almost as soon as Phase-1 funding is received in order to avoid funding gaps and reduced progress.

Shortening the time between Phase I and Phase II. Balancing awards and an award process where most of the Phase I’s awardees receive Phase II funding.

Faster grant reviews and quicker funding decisions.

Faster review cycles. Currently it takes approximately 1 year between conception of a research project and funding. Waiting on reviews or any feedback is sometimes detrimental to our company as the funding or non-funding of a project alters our strategic direction. Review feedback within a month or two after submission would be very helpful even if the actual funding comes later.

Faster turn-around time from grant deadline to notification to start date if successful.

Turn around the application reviews more quickly so there’s time for careful thought before resubmitting.

_______________

aIn some cases, Phase I grants are renewed for a second year of Phase I without having to compete against other SBIR applications for money. In NIH jargon, this is called a noncompeting renewal.

SOURCE: 2014 Survey

companies has become more difficult.18 On the other hand, these companies are setting up new incubator-type arrangements in a number of places. Johnson & Johnson recently announced four research centers—two in the United States, one in Massachusetts and one in California, one in China, and the one in the United Kingdom. Merck has established the California Institute for Biomedical Research (CB3) in San Diego to fund early-stage drug research. Bayer has partnered with the University of California, San Francisco, to support translational research.

_______________

18See Chapter 5 (Quantitative Outcomes) and Appendix E (Case Studies).

FIGURE 2-6 Seed-stage funding and deals for biotechnology and medical devices, 1995-2015.

SOURCE: PricewaterhouseCoopers/National Venture Capital Association MoneyTree™ Report, Data: Thomson Reuters.

NOTE: Accessed July 14, 2015. Customized for stage and industry sector.

Pfizer has also announced several academic relationships, aimed at providing early access to cutting-edge technology and relationships with academic leaders in their fields.19

Foundations have also started to provide funding for translational research. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has a $1 billion fund for venture philanthropy investing. It provided a $10 million investment round in Liquidia Technologies in 2010.20 It also invested $29.3 million in Sanaria (see Appendix E: Sanaria case study).

The extent to which these larger companies and other actors fill the gaps left by the retreating VCs is unclear, however. Only 15 percent of SBIR respondent companies had received funding from other companies.

Survey Data About Food and Drug Administration Approvals

Forty-six percent of respondents to the 2014 Survey reported that their projects required U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for drugs,

_______________

19Ed Mathers, “Life Science Startups Looking for New Sources of Funding,” Scale Finance, July 14, 2015.

20Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, “Liquida Technologies Receives Investment to Bolster Development of Vaccines,” March 4 2011.

TABLE 2-5 Current Status of Project in Relation to Clinical Trials

| Percentage of Respondents | ||||

| NIH Total | SBIR Awardees | STTR Awardees | PHASE IIB Awardees | |

| Process abandoned | 35.5 | 35.9 | 33.3 | 5.3 |

| Preparation under way for clinical trials | 34.4 | 35.5 | 28.2 | 47.4 |

| IND granted | 4.7 | 4.1 | 7.7 | 10.5 |

| In Phase I clinical trials | 4.7 | 5.1 | 2.6 | |

| In Phase II clinical trials | 9.4 | 7.4 | 20.5 | 15.8 |

| In Phase III clinical trials | 2.3 | 1.8 | 5.1 | |

| Completed clinical trials | 9.0 | 10.1 | 2.6 | 21.1 |

| BASE: NIH PROJECTS REQUIRING FDA APPROVALa | 256 | 217 | 39 | 19 |

a Due to a high percentage of the population that could not be reached, and a low response rate from those who were reached, the number of respondents is relatively small. Moreover, it is possible that companies that had abandoned the clinical process were disproportionately represented in the companies who could not be reached.

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 41.

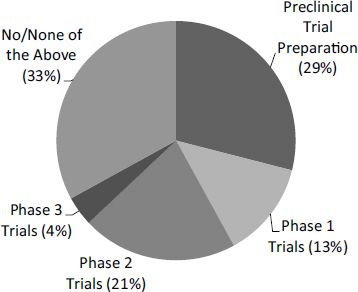

devices, and products. This sizable percentage underlines the importance of the FDA approval process for the eventual success of the program.21 Respondents that reported the need for FDA approval were asked about the current status of the project in relation to FDA approval (see Table 2-5). This is an important milestone; only 9 percent of projects requiring the need for FDA approval had completed clinical trials, with a further 2 percent in Phase III trials.

In contrast, more than twice as many Phase IIB respondents reported completion of clinical trials. Given that the funding is explicitly designed to support clinical trials, this is not surprising (see Chapter 3). Among all respondent companies, 35 percent had abandoned the clinical trials process for the surveyed project. A further one-third was in the preparatory stage as of 2014, and a further one-third was in the clinical trials process. A further 2 percent were engaged in Phase III trials. These figures illustrate the enormous challenges for small companies working in life sciences. The raw numbers for Phase IIB are very small (19 respondents), and Phase IIB only began in FY2005, so results should be interpreted with caution. Still, only 5 percent of Phase IIB respondent companies have abandoned the process, and 21 percent have completed clinical trials.

_______________

212014 Survey, Question 40.

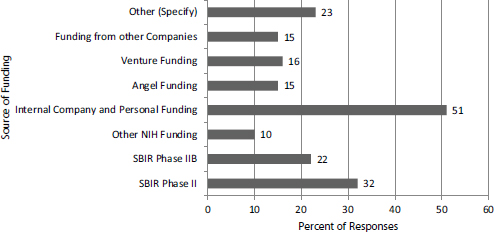

From another perspective, Phase IIB funding forms an important but not dominant element in the patchwork of funding that supports the efforts of SBIR/STTR projects to complete clinical trials (see Figure 2-7).

The 2014 Survey also asked about the completion of different clinical trials. Figure 2-8 shows that about a one-third of the 21 respondents indicated that the Phase IIB funding was not sufficient to complete Phase I clinical trials, while 4 percent (1 respondent) indicated that it had been sufficient for all three phases. The results (given the small number of respondents) are far from conclusive, but they suggest that Phase IIB can be seen as supporting most projects into Phase II trials.

Support Needed for FDA-related Activities

The need for FDA approval presents a financial challenge—for reasons discussed elsewhere—as well as a technical challenge: the requirements for acquiring FDA approval or even for entering the FDA approval process are not easy to satisfy, particularly for small businesses without expertise in this area.

Most of the case study companies have long since passed this point in the process and are quite knowledgeable about FDA requirements, but many of the survey respondents indicated that these challenges were formidable. Box 2-5 captures the range of concerns reported by these respondents.

Recommendations from survey respondents for improving NIH support for regulatory compliance included:

FIGURE 2-7 Sources of funding for clinical trials (percentage of respondents mentioning each source).

NOTE: Numbers do not sum to 100 percent because multiple answers were permitted.

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 42.

FIGURE 2-8 Clinical trial phase completed as a result of Phase IIB funding (percentage of respondents).

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 47.

- Access to an FDA consultant permanently attached to the SBIR/STTR programs.

- Provision of more or better educational materials and training at the start of the SBIR/STTR award cycle, to allow companies to better align their efforts with FDA requirements.

- Creation of a better and more durable connection between NIH and FDA, through which companies could be guided.

- Direct NIH support for FDA regulatory filings and paperwork.

- Preliminary FDA review of clinical plans approved by NIH for SBIR/STTR.

Responsibility for these recommended activities is shared between the NIH SBIR/STTR Program Office and the ICs. At the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), an FDA expert is currently part of the advisory service portfolio provided by its SBIR/STTR programs.22 However, it appears that for the programs as a whole and for many of the ICs, regulatory assistance is limited to a link to the FDA website.

_______________

22See OTAC Resources at NHLBI, http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/org/dera/otac/resources, accessed July 10, 2015.

BOX 2-5

2014 Survey Responses Related to FDA Approvals (Representative Comments)

Small businesses are often inadequately informed about the requirements and process for obtaining FDA approval for products they envision. Efforts by the NIH to (1) educate and encourage small businesses to appropriately approach the FDA for regulatory approval and (2) encourage the FDA to work with and facilitate the regulatory process for medical devices arising from NIH-funded small business and academic grants would be enormously helpful.

NIH really needs to provide some FDA trained regulatory people and a course that details what needs to be done to get an IND and beyond in clinical trials. There are a million consultants in this space, and without any knowledge beforehand, it is pretty daunting to pick a good one.

There is a huge disconnect between NIH and FDA. FDA is looking for more simple solutions to problems (i.e. one drug delivery) and NIH reviewers are typically looking at extremely innovative solutions, which FDA does not look favorably upon.

Direction regarding the preparation of documents and assembly of protocols to meet FDA requirements.

FDA guidance and some funding that are directed by awardee to work with an external regulatory expert.

. . . helping small business to receive from the FDA more clear guidance with respect to the Agency’s expectations regarding the supporting clinical data needed would be of a huge significance.

Some kind of review by FDA of the clinical research plan that is approved by NIH would be very helpful.

IND development training would have been helpful at the time of receiving the funds. The company took 3 drugs through IND into clinical trials so gained experience on its own but would have benefited from having regulatory training.

It would be great if the NIH hosted a web site, webinar, handouts, etc. explaining more clearly how to approach and work with the FDA; these materials should be oriented to small firms with no prior FDA experience.

It would be helpful if NIH had a program to help with FDA filings and document preparation. Companies at our stage have a tough time spending a large amount of resources on CROs for these services.

NIH should have an advocacy desk at the FDA. The FDA is the worst agency in the US to work with.

Small businesses are uneducated and intimidated by the requirements for obtaining FDA approval. NIH could assist by (1) facilitating appropriate timely communication between the small business and the FDA and (2) encouraging the FDA to reach out in a user-friendly way to small businesses.

SOURCE: 2014 Survey.

PHASE IIB

Phase IIB began in earnest in FY2005 after a short pilot program. Since then, NIH has awarded approximately 20 Phase IIB awards annually (see Chapter 4). Our research suggests that this funding is of great significance to awardees. More comments were received from the 2014 Survey about the need to bridge the funding gap around clinical trials than any other topic. Several case study companies had received Phase IIB awards, and in general they believed them to be helpful.

Awardees are concerned about the massive challenge of funding clinical trials. Dr. Tseng (TissueTech) said that bridge funding was his main concern while the company moved a product through the FDA regulatory pathway. This concern has been of declining importance for TissueTech, which has other resources available for this purpose, but Dr. Tseng believes it could be a critical problem for other companies. He noted that currently, SBIR funding is available for Phase I clinical trials, and it was barely possible—if resources were used very carefully—to complete Phase II clinical trials using SBIR Phase II awards. However, in most cases that was not possible—and many companies faced huge challenges in finding that funding.

Dr. Hogan (GMS) said that the Phase IIB program is an excellent idea. Because the valley of death is large and growing, such a program is critical in the absence of other NIH funding and declining interest in early-stage investments from venture capital firms and large pharmaceutical companies. In the current environment, he believes it is extremely difficult to attract outside funding if the company does not have a product ready to sell: it is not necessary to have substantial sales, but some sales should be imminent.23

Aside from numerous calls for more or larger Phase IIB awards, survey respondents also provided more detailed comments about the Phase IIB program (see Box 2-6).

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

Intellectual property under the SBIR/STTR programs is governed by two sets of regulations, which are not always in complete alignment.

In general, ownership of intellectual property generated from research grants made by the federal government is governed by the Bayh-Dole Act (1980). The Act provides that small businesses and nonprofit organizations (including universities) can elect to take title of inventions developed using federal funding. Before this, all inventions were automatically the property of the government.24

_______________

23The Valley of Death refers to the early stages of a startup, before a new product or service brings in revenue from real customers.

24David C. Mowery, et al. “The Growth of Patenting and Licensing by US Universities: An Assessment of the Effects of the Bayh–Dole Act of 1980.” Research Policy, 30(1): 99-119, 2001.

BOX 2-6

2014 Survey Respondent Comments on Phase IIB and the Need for Post-Phase II Funding (Representative Comments)

A mechanism should be established to financially assist companies to advance candidate products to clinical trials development (beyond phase I and Phase II programs).

All NIH institutes need to support Phase III commercialization grants. The Pharmaceutical Industry in the current environment will only partner with companies whose products have undergone Phase I or Phase II clinical trials.

Consider additional funding to help move the project through the FDA process, and if necessary perform an initial clinical trial.

Have ability to have Bridge grant re-award after completion of first Bridge grant. Increase the number of “bridging funds or grants” so that we can complete the planned FDA IND approval process.

Increased access to P2B funding to bridge from P2 to commercialization.

Increased availability of post Phase II funding to complete pre-clinical demonstration (typically on animals) and pursue FDA approvals.

More opportunities for RAID, or TRND or BRIDGE to assist in preclinical development.

Phase III to proceed with Product Development, Validation and Toxicity testing and to hire Consultants to help us interact/navigate the needs of the Federal Regulating/Licensing Agency. It was quite difficult to get it all together (2 years) to be able to fund raise from Venture Capitalists.

PIIB funding is challenging and given the current venture capital landscape is critical to companies.

Small companies need funding to offset the late stage clinical studies required for FDA approval of products. Current SBIR/STTR funding helps with early stage in vitro proof of concept work and early stage clinical trials (Phase 1 and possibly Phase 2). NIH funding is not available after this point. Depending on commercial opportunity and industrial partner comfort with the science, additional funding can be found. However really innovative science cannot always find additional funding.

The current system is quite adequate to validate an idea, build a prototype, and collect relevant biological data. That leaves a large financial barrier to cross in turning a prototype into a manufacturable product and bringing it to market. Whether NIH could or should address this issue is problematic. It is currently left to the private sector. Sadly, the private sector evaluates a technology solely on its financial potential rather than on whether the science is good and will predictably be beneficial. NIH has historically taken a broader view of the problem, a perspective that would lead to a number of important products being available to people who need them if such an involvement were possible.

To summarize, respondents indicated the following:

- Phase IIB is an important and welcome initiative

- In the current environment, Phase IIB often makes the difference at a key point in the commercialization process.

- The $3 million in funding would not be sufficient to complete Phase III clinical trials and in many cases would not be enough to complete Phase II.

- The matching fund restrictions imposed by NCI are onerous.

- The timeline for disbursement does not necessarily meet company needs, which might be clustered toward the start of the process.

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 53.

Inventions (as defined by federal law) that are made under SBIR/STTR awards are subject to the invention reporting requirements based on Bayh-Dole. For contractor organizations (which would generally include grantees), the agreement to disclose inventions to the government is included in the original grant or contract. Under these provisions, an invention report must be filed within 2 months of senior management becoming aware of the invention (at NIH using the electronic iEdison portal). The company then has 2 more years to claim title to the invention. Once the title has been claimed, the company then has 1 more year to file a patent application, although the company can apply for an extension of this time period.25

March-in rights are potentially granted to the government to take ownership of intellectual property in cases where the invention is not sufficiently commercialized. However, although this has been a concern in some cases at DoD and NASA, where prime contractors have been able to utilize technology developed under the SBIR program, march-in rights have been exercised infrequently at NIH. Four applications for march-in rights have been brought at NIH as of 2013, and all have been denied.26

Although inventions developed under the SBIR/STTR programs must follow the invention reporting mechanisms described in Bayh-Dole, the data rights described in the SBIR/STTR authorizing legislation are otherwise operative.27 These rights implicitly refer to intellectual property that is not patentable or has not been patented. Bayh-Dole refers only to patentable inventions and provides for a clear path through which companies can patent inventions funded by federal agencies.

_______________

25iEdison Invention Timeline, http://era.nih.gov/iedison/invention_timeline.cfm, accessed February 14, 2014.

26William O’Brien, O’Brien, “March-in Rights Under the Bayh-Dole Act: The NIH’s Paper Tiger?,” Seton Hall Law Review, 30: 1403, 2013.

27Ronald S. Cooper, “Purpose and Performance of the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Program,” Small Business Economics 20(2): 137-151, 2003.