2

Partners in Research and Oversight

The United States maintains a research enterprise that is world renowned for its productivity, innovation, and dynamism. A core part of this enterprise is the well-established partnership between the federal government and research institutions. Research institutions perform fundamental and applied research while also educating and training the next generation of researchers, scholars, and leaders. This partnership, which was deliberately established, has been extraordinarily successful, and is internationally recognized for achieving significant advances in scientific and engineering research for the benefit of society. However, the regulation of this partnership, while longstanding, necessary, and constructive, has grown to such an extent that it may now impede the advance of discovery and diminish returns on the public investment.

CHARACTER AND OUTCOMES OF THE PARTNERSHIP

The partnership between the federal government and research institutions emerged in the aftermath of World War II,1 when national leaders recognized the importance of the contribution of basic and applied research to the war effort, comprehended its significance to national prosperity and strength, and deliberately established a means to maintain it. Upon extensive reflection, and with visionary institutional thinking and considerable debate, a partnership was forged that was decentralized (rather than embedded, for example, within a single ministry of science and technology), merit based (awarding research funds on the basis of peer evaluation and determination of scientific quality and significance rather than, for example, on geographical dispersion or seniority of applicants), and overseen by federal agencies, primarily to ensure accountability in

___________________

1The advancement of the scientific enterprise has, however, been a national aspiration since the nation’s founding. This aspiration is stated explicitly in United States Constitution in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8. The clause gives Congress the specific power “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts” by providing intellectual property protections for authors and inventors.

the use of public funds.2 Implicit in the formulation of the partnership was the presumption that research institutions would accept primary responsibility to enable, administer, and oversee faculty conduct of research.

Within the partnership, research universities continue to exercise autonomy in providing their faculties with the freedom to decide what and how they teach and the research questions they choose to pursue. At the institutional level, governing boards with substantial independence guide institutions. That said, research institutions are nonetheless accountable to the taxpayers and other funders (e.g., foundations, industry) 3 supporting their research.

The partnership is without precedent. It has resulted in the most preeminent and productive research universities in the world. These institutions are the product of an extraordinary confluence of factors: “…the right values and social structures, exceptionally talented people, enlightened and bold leadership, a commitment to the ideal of free inquiry and institutional autonomy from the state, a strong belief in competition among universities for talent, and unprecedented, vast resources directed at building excellence to create an unparalleled system of higher learning.”4

A 2014 study evaluating 500 of the world’s universities largely on research performance identified 16 of the top 20 as U.S. institutions, and 32 U.S. institutions in the top 50.5 U.S. universities where fundamental research is pursued with federal funding also have been the home institutions of more Nobel Prize winners in the sciences than universities in any other country. The array of Nobel Prize recipients also demonstrates how effectively U.S. research universities attract top talent from elsewhere: 32 percent of laureates who won their Nobel Prizes while at a U.S. research university were foreign born.6

___________________

2On the origins of the partnership, see Jonathan R. Cole, The Great American University: Its Rise to Preeminence, Its Indispensable National Role, Why It Must be Protected (New York: Public Affairs, 2012); James J. Duderstadt, A University for the 21st Century (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000); and Homer A. Neal, Tobin L. Smith, and Jennifer B. McCormick, “Beyond Sputnik: U.S. Science Policy in the 21st Century,” Review of Policy Research 26, no. 3 (2009): 345-346.

3Robert M. Berdhal, “Research Universities: Their Value to Society Extends Well Beyond Research,” Association of American Universities, April 2009, https://www.aau.edu/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=8740.

4Jonathan R. Cole, The Great American University: Its Rise to Preeminence, Its Indispensable National Role, Why It Must be Protected (New York: Public Affairs, 2012).

5“Academic Ranking of World Universities 2014,” Center for World-Class Universities at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, 2015, http://www.shanghairanking.com/ARWU2014.html.

6“The United States is also unique in the scale on which it attracts human capital: of the 314 laureates who won their Nobel prize while working in the U.S., 102 (or 32%) were foreign born, including 15 Germans, 12 Canadians, 10 British, 6 Russians and 6 Chinese (twice as many as have received the award while working in China). Compare that to Germany, where just 11 out of 65 Nobel laureates (or 17%) were born outside of Germany (or, while it still existed, Prussia). Or to Japan, which counts no foreigners at all

The partnership has been remarkably productive, whether measured in direct scientific output, in the expertise and capabilities of each generation of researchers and scholars they train, or in economic impact.7 Over several decades, the partnership has yielded discoveries and knowledge that have had an immense effect and impact—from the Internet to genomics, from barcodes to the understanding of black holes, from breakthrough accomplishments in major scientific fields to the creation of entirely new fields of study. The contributions of the U.S. research enterprise are unparalleled.8

But the research enterprise yields much more than knowledge. It has given the nation a system of higher education that consistently attracts to its faculties and student bodies top talent from around the world. U.S. research universities provide a trained workforce with direct experience in research—devising new lines of inquiry, conducting experiments, analyzing outcomes, generating new knowledge—that equips graduates not only for careers in science and engineering but also in the rapidly changing knowledge industries, and indeed for leadership in any field.9

The success of the research enterprise can be conveyed by its effect on U.S. economic performance. Based on work initiated by Robert Solow and since pursued in an extended body of economic literature, economists attribute as

___________________

among its nine Nobel laureates.” Jon Bruner, “American Leadership in Science, Measured in Nobel Prizes [Infographic],” Forbes, October 5, 2011, http://www.forbes.com/sites/jonbruner/2011/10/05/nobel-prizes-and-american-leadership-in-science-infographic/.

7Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, and National Academy of Engineering, “Why Are Science and Technology Critical to America’s Prosperity in the 21st Century?” in Rising Above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and Employing America for a Brighter Economic Future (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2007), pp. 41–67.

8The accomplishments of federally funded research at U.S. research universities are far too numerous to convey in a single note. For some displays of the impressive outcomes of federally funded research, see “Nifty 50,” National Science Foundation, accessed August 11, 2015, http://nsf.gov/about/history/nifty50/index.jsp.

National Academy of Sciences, Beyond Discovery: The Path from Research to Human Benefit, accessed August 11, 2015, http://www.nasonline.org/publications/beyonddiscovery.

University-Discoveries.com, “Discoveries & Innovation that Changed the World,” accessed August 11, 2015, http://university-discoveries.com/.

National Institutes of Health, “NIH…Turning Discovery into Health,” August 15, 2012, http://nih.gov/about/discovery/index.htm.

See also Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences, and National Academy of Engineering, Rising Above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and Employing America for a Brighter Economic Future (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2007).

9Keith Yamamoto, Vice Chancellor for Research, Executive Vice Dean of the School of Medicine, and Professor of Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology, University of California, San Francisco, Presentation to the Committee, May 28, 2015.

much as half of U.S. economic growth over the past 50 years to scientific advances and technical innovations.10

The means by which university research contributes to the economy are many. They include not only the translation of knowledge into products and applications and the employment that stems from such results but also the training of scientists and engineers for industry and the creation of entirely new areas of economic activity.

Atkinson and Pelfrey indicate that approximately 80 percent of leading industries today are the result of research conducted at academic institutions.11 For example, federally supported research in fiber optics and lasers helped create the telecommunications and information technology industries that now account for one-seventh of the U.S. economy.12 Research in fundamental molecular biology and in chemistry, sustained for decades with federal financing, led to the development of biotechnology and made possible the multibillion dollar pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries that have contributed to the health and well-being of individuals around the world.13 Further, research institutions across the nation have contributed immensely to the economies of their regions, creating hubs of innovation and employment in high-technology and knowledge-intensive industries.14

DIVERSITY OF EACH PARTNER

The members of the research partnership are generally identified as the fed-

___________________

10For discussion and references, see Homer A. Neal, Tobin L. Smith, and Jennifer B. McCormick, “Beyond Sputnik: U.S. Science Policy in the 21st Century,” Review of Policy Research 26, no. 3 (2009): 345–346.

11Richard C. Atkinson and Patricia A. Pelfrey, “Science and the Entrepreneurial University,” Issues in Science and Technology XXVI, no. 4 (Summer 2010).

12Homer A. Neal, Tobin L. Smith, and Jennifer B. McCormick, “Beyond Sputnik: U.S. Science Policy in the 21st Century,” Review of Policy Research 26, no. 3 (2009): 345–346.

13The existence of the biotechnology industry provides a powerful and compelling example of the measurable contributions of fundamental research to the economy. A recent study of the economic impact of licensing resulting from academic biotechnology research suggests contributions to gross domestic product ranging from $130 billion to $518 billion in the period from 1996 to 2013 (in constant 2009 U.S. dollars). In the same time period, the study estimates that sales of products licensed from U.S. universities, hospitals, and research institutes supported between 1.1 and 3.8 million “person years of employment.” Lori Pressman, David Roessner, Jennifer Bond, Sumiye Okubo, and Mark Planting. The Economic Contribution of University/ Nonprofit Inventions in the United States: 1996–2013 (Washington, DC: Biotechnology Industry Organization), https://www.bio.org/sites/default/files/BIO_2015_Update_of_I-O_Eco_Imp.pdf.

14See Iryna Lendel, “The Impact of Research Universities on Regional Economies: The Concept of University Products,” Economic Development Quarterly 24, no. 3 (2010): 210-230.

eral government and research institutions, as though each were a single entity. In fact, the “halves” of this partnership are composed of many diverse entities.

The involvement of the federal government in the research enterprise is not overseen by a single office. Unlike in some countries, the U.S. government does not confine its funding of research within a single ministry. Rather, it supports and oversees research via a diverse and decentralized array of agencies and offices with different missions, mandates, budgets, and institutional profiles. These include cabinet-level entities, such as the Departments of Defense (DOD), Energy, and Health and Human Services (HHS), and other agencies such as the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. There are also many offices and institutes within individual agencies (e.g., the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration within the Department of Commerce). The National Institutes of Health (NIH), itself located within HHS, houses 27 institutes and centers. In addition to funding research at universities, some of these entities conduct their own mission-related scientific research and maintain their own laboratories.

U.S. research universities may engage with more than 20 different agencies when seeking federal research support (see Box 2-1). This multiplicity is both a boon to researchers (as the decentralization provides diversity in research priorities) and a hindrance (due to inconsistencies in agency policies and requirements).

Because of their relationships with federal research funding agencies, research institutions interact with a host of other government entities (e.g., Congress, the auditing community, and national laboratories) involved in the support, oversight, or conduct of federally funded research.

Research universities include private and public institutions of varying sizes. Some have enviable endowments, others depend on shifting state budgets, and others are strongly dependent on tuition income and other revenue sources.15 Some include prominent medical schools and hospitals; others excel at engineering or agriculture. Some have a single campus; others represent an affiliation of many independent campuses. Some are able to provide extensive administrative assistance to faculty engaged in research; others can provide only limited support.

By some measures, research institutions are a special few. Among nearly 5,000 institutions of higher education in the United States, 108 are classified as research institutions with very high research activity. Another 99 institutions are classified as research universities with high research activity.16 While federal

___________________

15See Finances of Research Universities (Washington, DC: Council on Government Relations An Association of Research Universities, 2008), http://www.cogr.edu/viewDoc.cfm?DocID=151534.

16“The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education,” About Carnegie Classification, accessed August 12, 2015, http://carnegieclassifications.iu.edu//.

funds for research are distributed to universities across the nation,17 the top 100 institutions receive approximately 80 percent of all federal funding for research at universities. The diversity of these top 100 universities (see Appendix D) shapes the regulatory landscape. They engage with different agencies supporting diverse portfolios of research, many of which have different approaches and policies regarding common concerns. And these diverse institutions must respond to federal funding levels that can vary from year to year in terms of both the levels of support and the focus of funding opportunities.

___________________

17For a map of the distribution, see “Federal Science Funding Information Factsheets,” Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 2014, accessed August 12, 2015, http://www.faseb.org/Policy-and-Government-Affairs/Become-an-Advocate/FederalScience-Funding-Information-Factsheets.aspx.

PATTERNS IN FEDERAL INVESTMENT IN RESEARCH

Today, the President’s overall FY 2016 budget provides $146 billion for federal research and development (R&D), including the conduct of R&D and investments in R&D facilities and equipment.18 Proposed FY 2016 funding for basic research is $32.7 billion and $34.2 billion for applied research (see Appendix F).19

Historical trends reveal significant shifts in the scale and composition of federal support. Over the many decades that the federal government has invested in research, priorities have changed. During the Cold War and particularly after the Soviet launch of Sputnik, federal support of research increased substantially. During this time, a significant portion of funding was devoted to space-related research. In the 1990s, congressional focus shifted to health research and provided additional support to research that might offer cures for disease.20

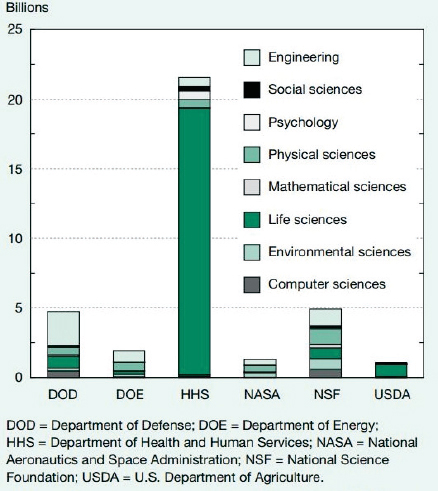

HHS, primarily through NIH, channels more funding to research universities than any other federal agency (see Figure 2-1). DOD has consistently been the largest supporter of academic engineering research. NSF is the only federal agency with responsibility for basic research and education across all areas of science and technology. While it does not fund biomedical research, it does fund basic biological sciences research. It also supports science and math education programs from kindergarten, through high school, and into college.

___________________

18Fiscal Year 2016 Analytical Perspectives of the U.S. Government (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2015), p. 293, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2016/assets/spec.pdf. The amount of $146 billion represents a 5.5 percent increase over the 2015 enacted level of $138 billion (which may change as agency operating plans are finalized).

19Ibid, p. 298.

20As the largest funder of research at universities, NIH’s budget reflected increases of 14 to 16 percent from FY 1998 to 2003, but has declined in constant dollars by about 25 percent since 2003.

SOURCE: National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Higher Education Research and Development Survey, FY 2012. See appendix table 5-4.

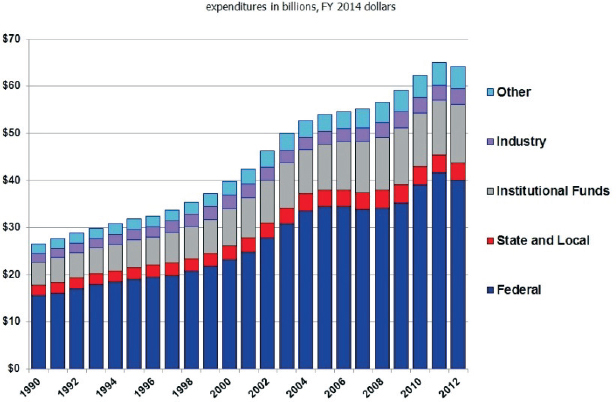

While the federal government has been the major funder of research at universities since the government-university partnership was established, it is not the only source of support (see Figure 2-2). State and local governments also provide funding, as do foundations and industry (although the latter generally supports applied research and development rather than basic research). As Figure 2-2 illustrates, universities are increasingly redirecting their own funds (whether from state appropriations, tuition, gifts, endowments, or other sources) to support research. NSF data indicate that over the past 20 years, the university share of support for research has grown faster than any other sector. Universities are the second leading sponsor of university research, providing nearly 20 percent of the total funding. This exceeds the combined total of state, industry, and foundation support by 10 percent.21 University support has become more necessary, as the limit on federal reimbursement for administration (capped at 26 percent since the early 1990s)22 does not permit universities to recoup the full cost

___________________

21National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, National Science Foundation, 2014, accessed August 12, 2015, http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/.

22The 26 percent cap applies to the administration portion of Facilities and Administrative (F&A) costs.

of complying with federal regulations on research (the only class of recipient organizations so restricted).

SOURCE: National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Higher Education R&D series, based on national survey data. Includes Recovery Act Funding. ©2014, AAAS.

THE IMPORTANCE OF REGULATIONS TO FEDERALLY FUNDED RESEARCH

Increases in funding for academic research have been accompanied by consistently increasing federal oversight. Given the significant investment of taxpayer dollars and the potential risks to study participants, the public, and researchers themselves, the need for federal oversight is clear. Indeed, federal oversight is recognized by research universities as being in their own interest. When an individual case of research malfeasance occurs—whether in the form of misuse of funds, research misconduct, mishandling of materials, or harm to research participants—universities and the federal government are also among the victims. When exercised well, oversight protects the government, universities, research participants, investigators, and the public.

Federal regulations address financial accountability for federal funds, the conduct of research, and public welfare. Regulations directed at financial accountability seek to ensure that federal research funds are suitably charged, properly expended, and wisely used. Regulations seek to promote the efficient and effective use of federal funds while preventing theft, fraud, or abuse. Financial accountability is required throughout the research funding process, from the submission of preliminary budgets in initial research proposals to the final closeout of an award and continuing through subsequent audits.

Federal regulations also address the conduct of research, particularly the safety, rights, and welfare of human subjects and the welfare of animals. Federal oversight of human participants concerns not only human welfare and safety but also the process of obtaining acknowledgment that the participant is aware of the risks involved in the research, is cognizant of privacy issues that might arise, and, understanding these facts, knowingly consents to participate in the research. Any risk to human participants must be deemed proportionate to the potential benefits of the research. Vulnerable populations (such as minors and prisoners) are protected by additional safeguards. At the level of the institution, oversight of the use of human participants in scientific research is accomplished through institutional review boards. Any institution that uses animals in federally funded research is required to have an institutional animal care and use committee to inspect facilities and review research protocols. Those protocols must include the rationale for using animals, provide an account of procedures that will be used in the research, and describe the techniques that will be used to minimize animal discomfort. Accrediting organizations23 assist institutions with the development of measures and procedures designed to ensure that human and animal research participants are treated appropriately.

Research universities are partners in ensuring research integrity and the safety of all involved. Because some research is risky, research institutions implement their own standards and policies that are designed to ensure safe practices. Because research misconduct and careless science harm the entire research enterprise, universities also have an interest in sanctioning abuses. Funding agencies can impose a range of sanctions on researchers found guilty of misconduct. These include removal from research projects, debarment from participation in agency review panels, and temporary or permanent prohibitions on receipt of federal research funding. Institutions also can impose sanctions that include dismissal of transgressors. Although institutional personnel policies generally prevent incidents of malfeasance from becoming public, universities do reprimand and can dismiss investigators deemed culpable of research misconduct or other transgressions. Moreover, the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) Office of Research Integrity, which receives and reviews the institutional files and actions in all cases of scientific misconduct in research funded by a PHS agency, publishes its findings whenever it finds a researcher guilty of scientific misconduct.

Federal oversight of scientific research extends to public safety. This broad category includes regulations regarding the handling of materials such as toxic

___________________

23Accreditation by the Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs (AAHRPP), Inc. demonstrates that an institution has rigorous standards in place for the protection of human research subjects. Accreditation by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International demonstrates that an institution has rigorous standards in place to ensure the humane treatment of research animals.

chemicals or radioactive reagents that could be harmful to the researchers and the public if released into the environment. This category also includes controls on materials, technology, or information deemed “dual use”—that is, that could be used to do harm if misapplied. Export Controls, International Traffic in Arms Regulations, Select Agent Rules, and Dual Use Research of Concern policies are all examples of regulations designed to address public safety concerns.

Expenditures of taxpayer dollars should not occur without adequate accountability. Research universities are partners in this effort. Although research grants are often identified with their principal investigator, legally a research grant received by a faculty member at a university is a grant to that institution and not to the individual. Every proposal to a federal funding agency must therefore be reviewed and approved by the university before submission. Review entails determining that planned expenditures are appropriate and allowable, listed salaries are correct, proper costs will be charged for facilities and administration, and necessary research protocols have been reviewed and approved.

HOW THE GOVERNMENT FUNDS ACADEMIC RESEARCH

Since the beginning of the partnership, the federal government funded both the “direct” costs of research (i.e., the costs of personnel, supplies, and equipment needed to conduct research) plus the “indirect” costs (or Facilities and Administrative [F&A] costs)24 (i.e., those costs associated with maintaining research facilities, managing hazardous and radioactive waste, and supporting administrative oversight and management of federal research awards.) Indirect costs are costs for activities that benefit more than one project and which are difficult to ascribe to an individual project. An institution’s F&A rate is awarded by the federal government to each university on the basis of a proposal that each institution submits every 3 to 5 years following review and negotiation with the institution’s cognizant federal agency.

In 1991, regulations changed. Following publicity of allegations of violations at one institution that were perceived to be widespread, the federal government imposed a 26 percent cap25 on the federal reimbursement of the admin-

___________________

24“F&A costs are shared expenses related to university facilities and administration. Facilities costs are defined as allowances for depreciation and use of buildings and equipment; interest on debt associated with buildings and equipment placed into service after 1982; operation and maintenance expenses, and library expenses. Administrative Costs are defined as general administration and general expenses such as the central office of the university president, financial management, general counsel, and management information systems; departmental administration; sponsored-projects administration; and student administration and services that are excluded or limited when computing rates for research.” Analysis of Facilities and Administrative Costs at Universities (Washington, DC: Office of Science and Technology Policy, 2000), p. 3, https://www.whitehouse.gov/files/documents/ostp/NSTC%20Reports/Analysis%20of%20Facilities%202000.pdf.

25Via a 1991 revision of Circular A-21.

istrative component of a university’s indirect costs. Even though federal regulations and other administrative requirements have increased over the proceeding decades, the administrative component of the indirect cost rates has remained unchanged at 26 percent. As a consequence, universities have been required to increase their use of institutional funds to pay for the administrative component of the indirect costs of research. While some universities may have the resources to cover these unreimbursed costs for the present, an increasing number of both private and public universities may not. 26

THE GROWTH AND COST OF REGULATION

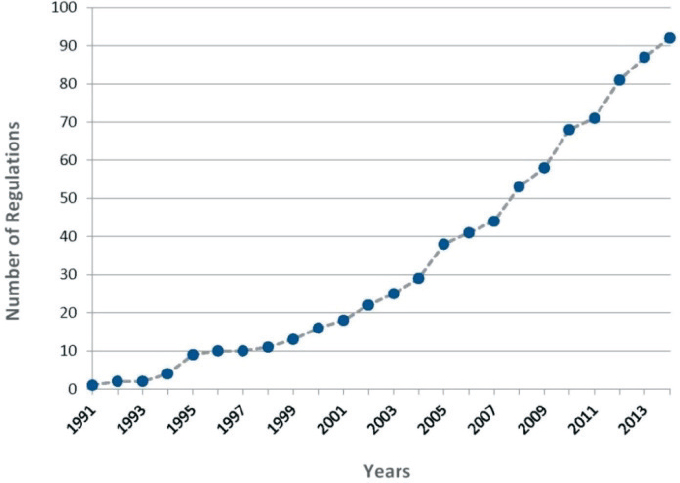

Although regulation and oversight are essential elements of the research enterprise, they have increased dramatically in recent decades (see Figure 2-3). The regulations, policies, and guidance issued by many different federal agencies, and sometimes by Congress itself, are at times duplicative, conflicting, or ineffective in meeting goals of improved accountability, efficiency, or perhaps even safety. Further, incomplete and conflicting guidance on how to comply, as well as audit practices that depart from stated agency policies, have created uncertainty and confusion for researchers and universities.27

Regardless of whether the data indicates a dramatic escalation in the number of regulatory changes or whether it is consistent with a long-term trend, the pattern is concerning. The increase in just this time period has been dramatic. “In the 1990s, the federal government promulgated approximately 1.5 new or substantially changed federal regulations and policies per year that ‘directly affect[ed] the conduct and management of research under Federal grants and contracts.’ In the

___________________

26See Finances of Research Universities (Washington, DC: Council on Government Relations An Association of Research Universities, 2008), http://www.cogr.edu/viewDoc.cfm?DocID=151534.

27The challenges of complying with duplicative and conflicting regulations have not been lost on federal sponsors of academic research. Agencies have frequently undertaken efforts to reduce regulatory burden. As far back as 1999, NIH undertook “an initiative to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of its overall research mission by reducing regulatory burden being experienced by the research community” and sought “potential solutions for the issues that emerged.” See NIH Initiative to Reduce Regulatory Burden: Identification of Issues and Potential Solutions, Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, Office of Extramural Research, 1999, accessed August 12, 2015, http://grants.nih.gov/archive/grants/policy/regulatoryburden/.

More recently, the U.S. Department of Agriculture issued a proposed rule as part of the agency’s review of its regulations and information collections. The proposed rule invites “public comment to assist in analyzing…existing significant [USDA] regulations to determine whether any should be modified, streamlined, expanded, or repealed.” See “Identifying and Reducing Regulatory Burdens,” Federal Register 80, no. 51 (March 17, 2015): 13789, https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/03/17/2015-05742/identifying-and-reducing-regulatory-burdens.

past decade (2003-2012), this number has increased to 5.8 per year.” See “Sustaining Discovery in Biological and Medical Sciences: A Discussion Framework,” Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 2015, accessed September 9, 2015, http://www.faseb.org/SustainingDiscovery/Home.aspx.

Regulations add cost to the research enterprise, particularly as they accumulate over time. The cost of regulation has been estimated in many ways. In recent testimony before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, Vanderbilt Chancellor Nicholas Zeppos, stated that Vanderbilt spends “approximately $146 million annually on federal compliance,” which represents about “11 percent of our non-clinical expenses.” Dr. Zeppos further noted that “as a major research institution with nearly $500 million annually in federally supported research, a significant share of this cost is in complying with research-related regulations.”28

___________________

28Recalibrating Regulation of Colleges and Universities: A Report from the Task Force on Government Regulation of Higher Education: Hearing Before the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, United States Senate, 114th Cong. (2015) (statement of Nicholas S. Zeppos, Chancellor, Vanderbilt University). These figures have come under scrutiny. See, e.g., G. Blumenstyk, “The Search for Vanderbilt’s Elusive Red-Tape Study,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, July 22, 2015.

SOURCE: Courtesy of the Federal of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 2015. Based upon data selected by the Council on Government Relations.

a The year of the implementation of the 26 percent cap on administrative costs in the F&A Cost stipulated under OMB Circular A-21 (Cost Principles for Education Institutions). This graph should not be read as implying that there were zero regulations prior to 1991. Compilation of this data began in response to the implementation of the cap. It would be difficult to collect a complete list for years prior to 1991, as some regulatory changes might have affected only a small segment of research and therefore, may be easily overlooked. Regardless of whether the data indicates a dramatic escalation in the number of regulatory changes or whether it is consistent with a long-term trend, the pattern is concerning. The increase in just this time period has been dramatic. “in the 1990s, the federal government promulgated approximately 1.5 new or substantially changed federal regulations and policies per year that “directly affect[ed] the conduct and management of research under Federal grants and contracts.’ In the past decade (2003-2012), this number has increased to 5.8 year.” See “Sustaining Discovery in Biological and Medical Sciences: A Discussion Framework,” Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 2015, accessed September 9, 2015, http://www.faseb.org/SustainingDiscovery/Home.aspx.

The specific regulatory changes referred to in the graph are as follows:

| Year | Federal Regulatory Change |

|---|---|

| 1991 | Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (Common Rule, 1991) |

| 1992 | Nonindigenous Aquatic Nuisance Prevention & Control Act of 1990 (Implemented, 1992) |

| 1994 | Deemed Exports (1994, EAR & ITAR) |

|

NIH Guidelines for Research Involving Recombinant DNA Molecules (1994) |

|

| 1995 | Conflict of Interest, NSF Financial Disclosure Policy (1995) |

|

Conflict of Interest, Public Health Service/NIH Objectivity in Research (1995; Amendments Proposed 2010) |

|

|

Cost Accounting Standards (CAS) in OMB Circular A-21 (1995) |

|

|

Executive Order 13224, Blocking Property and Prohibiting Transactions With Persons Who Commit, Threaten to Commit or Support Terrorism (September 2001, also EO 12947, 1995) |

|

|

Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 (Amended 2007) |

|

| 1996 | Health Insurance Portability & Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Privacy Rule |

| 1998 | OMB Elimination of Utility Cost Adjustment (UCA) (1998) |

| 1999 | Data Access/Shelby Amendment (FY 1999 Omnibus Appropriations Act); |

|

Policy on Sharing of Biomedical Research Resources (NIH, 1999) |

|

| 2000 | HHS Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) National Coverage Determination for Routine Clinical Trials (Clinical Trials Policy), 2000 |

|

Misconduct in Science (Federalwide Policy, 2000) |

|

|

Health and Human Services/FDA Clinical Trials Registry (2000, Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007; Mandated Reporting, 2008) |

|

| 2001 | Executive Order 13224, Blocking Property and Prohibiting Transactions With Persons Who Commit, Threaten to Commit or Support Terrorism (September 2001, also EO 12947, 1995) |

|

NEH, 2001, Misconduct in Science (Federalwide Policy, 2000) |

|

| 2002 | CIPSEA Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act (OMB Implementation Guidance 2007, Title V, E Government Act of 2002) |

|

FISMA Federal Information Security Management Act (Title III, E Government Act of 2002) OMB Circular A-130, Management of Federal |

|

|

Information Resources, Appendix III, Security of Federal Automated Information Systems |

| Year | Federal Regulatory Change |

|---|---|

|

NSF, 2002, Misconduct in Science (Federalwide Policy, 2000) |

|

|

Select Agents & Toxins (under CDC and USDA/APHIS) Public Health Security & Bioterrorism Preparedness & Response Act of 2002; companion to the USA PATRIOT Act (2001) |

|

| 2003 | Consolidation of Agencies’ Governmentwide Debarment & Suspension Common Rule (2003). Office of Management & Budget Guidance for Governmentwide Debarment and Suspension [Nonprocurement] (2CFR Part 180, 2006) |

|

Data Sharing Policy (NIH, 2003) |

|

|

EPA, Directive, 2003, Misconduct in Science (Federalwide Policy, 2000) |

|

| 2004 | Higher Education Act, Section 117 Reporting of Foreign Gifts, Contracts and Relationships (20 USC 1011f, 2004) |

|

Homeland Security Presidential Directive (HSPD) – 12, Common Identification Standards for Federal Employees and Contractors (2004) |

|

|

Labor, 2004, Misconduct in Science (Federalwide Policy, 2000) |

|

|

Model Organism Sharing Policy (NIH, 2004) |

|

| 2005 | Constitution & Citizenship Day (2005, Consolidated Appropriations Act FY 2005) |

|

Education, 2005, Misconduct in Science (Federalwide Policy, 2000) |

|

|

Energy, 2005, Misconduct in Science (Federalwide Policy, 2000) |

|

|

Genomic Inventions Best Practices (2005) |

|

|

HHS/PHS, 2005, Misconduct in Science (Federalwide Policy, 2000) |

|

|

NASA, 2005, Misconduct in Science (Federalwide Policy, 2000) |

|

|

Transportation, 2005, Misconduct in Science (Federalwide Policy, 2000) |

|

|

Veterans Affairs, 2005, Misconduct in Science (Federalwide Policy, 2000) |

|

|

Nuclear Regulatory Commission Order Imposing Fingerprinting and Criminal History Records Check Requirements for Unescorted Access to Certain Radioactive Materials (Feb 2008, Section 652, Energy Policy Act of 2005) |

|

| 2006 | America COMPETES Act 2006 |

|

Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act (FFATA) Executive Compensation and Subrecipient Reporting (2006) |

|

|

Office of Management & Budget Guidance for Governmentwide Debarment and Suspension [Nonprocurement] (2 CFR Part 180, 2006) |

|

| 2007 | CIPSEA Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act (OMB Implementation Guidance 2007, Title V, E Government Act of 2002) |

|

Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 (Amended 2007) |

|

|

Health and Human Services/FDA Clinical Trials Registry (2000, Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007; Mandated Reporting, 2008) |

|

| 2008 | Certification of Filing and Payment of Federal Taxes (Labor, HHS, Education and Related Agencies Appropriations Act of 2008, Division G, Title V, Section 523) |

|

Code of Business Ethics & Conduct (FAR) 2008 |

|

|

Combating Trafficking in Persons (2008) |

|

|

Health and Human Services/FDA Clinical Trials Registry (2000, Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act of 2007; Mandated Reporting, 2008) |

|

|

Homeland Security Chemical Facilities Anti-Terrorism Standards (CFATS) 2008 |

|

|

Military Recruiting and ROTC Program Access (2008, Solomon Amendment, National Defense Authorization Act for FY 2005) |

|

|

National Institutes of Health Public Access Policy (2008, Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2008, Division G, Title II Section 218) |

|

|

Nuclear Regulatory Commission Order Imposing Fingerprinting and Criminal History Records Check Requirements for Unescorted Access to Certain Radioactive Materials (February 2008, Section 652, Energy Policy Act of 2005) |

|

|

National Institutes of Health Policy for Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS, 2008) |

|

| 2009 | E-Verify 2009 |

|

Executive Order 13513, Federal Leadership on Reducing Text Messaging While Driving (October 2009) |

|

|

National Institutes of Health Guidelines for Human Stem Cell Research (2009) |

|

|

National Science Foundation Post-Doctoral Fellows Mentoring (America COMPETES Act 2006; implemented 2009) |

|

|

USAID Partners Vetting System (re: EO 13224 et al. re: terrorist financing 2009) |

|

| 2010 | OMB Open Government Directive, April 2010); Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act (FFATA) Executive Compensation and Subrecipient Reporting (2006) |

| Year | Federal Regulatory Change |

|---|---|

| 2010 | OMB Open Government Directive, April 2010); Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act (FFATA) Executive Compensation and Subrecipient Reporting (2006) |

|

(Compliance with § 872, National Defense Authorization Act of 2009, PL 110-417; as amended, 2010); Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) and Office of Management & Budget Federal Awardee Performance and Integrity Information System (FAPIIS) and Guidance for Reporting and Use of Information Concerning Recipient Integrity and Performance (2010) |

|

|

DFARS Export Control Compliance Clauses (2010) - Deemed Exports (1994, EAR & ITAR) |

|

|

FAR, July 2010; Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act (FFATA) Executive Compensation and Subrecipient Reporting (2006) |

|

|

Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) and Office of Management & Budget Federal Awardee Performance and Integrity Information System (FAPIIS) and Guidance for Reporting and Use of Information Concerning Recipient Integrity and Performance (2010) (Compliance with § 872, National Defense Authorization Act of 2009, PL 110-417; as amended, 2010) |

|

|

Federal Acquisition Regulations [FAR] Flowdown of Debarment/Suspension to Lower Tier Subcontractors (December 2010; amendment to FAR Subpart 9.4), Office of Management & Budget Guidance for Governmentwide Debarment and Suspension [Nonprocurement] (2CFR Part 180, 2006) |

|

|

National Institutes of Health, Budgeting for Genomic Arrays for NIH Grants, Cooperative Agreements and Contracts (2010) |

|

|

National Science Foundation Public Outcomes Reporting (America COMPETES Act 2006; implemented 2010) |

|

|

National Science Foundation Responsible Conduct of Research Training (America COMPETES Act 2006; implemented 2010) |

|

|

USDA, 2010, Misconduct in Science (Federalwide Policy, 2000) |

|

| 2011 | Homeland Security/Citizenship & Immigration Services I129 Deemed Export Certification for H1B Visitors (November 2010; implementation postponed to February 2011) |

|

Nuclear Regulatory Commission - Statement concerning the Security and Continued Use of Cesium-137 Chloride Sources (July 2011) |

|

|

America Invents Act 2011 Patent Regulatory Changes (2012): Implementation of First Inventor to File System |

|

| 2012 | Select Agents & Toxins (under CDC and USDA/APHIS) Public Health Security & Bioterrorism Preparedness & Response Act of 2002; companion to the USA PATRIOT Act (2001); revised October 2012 |

|

USAID Partners Vetting System (re: EO 13224 et al. re: terrorist financing 2009; Extension to Acquisitions, 2012) |

|

|

Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) and Office of Management & Budget Federal Awardee Performance and Integrity Information System (FAPIIS) and Guidance for Reporting and Use of Information Concerning Recipient Integrity and Performance (2010; 2012) (Compliance with § 872, National Defense Authorization Act of 2009, PL 110-417; as amended, 2010) |

|

|

America Invents Act 2011 Patent Regulatory Changes (2012): Implementation of First Inventor to File System |

|

|

NASA/OSTP China Funding Restrictions (2012, Under PL 112-10 1340(2) and PL 112-55 539) |

|

|

US Government Policy for the Oversight of Life Science Dual Use Research of Concern (March 2012) |

|

|

Food and Drug Administration Reporting Information Regarding Falsification of Data (April 2012) |

|

|

National Science Foundation Career-Life Balance Initiatives (2012) |

|

|

Gun Control, Prohibition on Advocacy & Promotion (Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2012 - PL 112-74, Sec 218) |

|

|

Conflicts of Interest, Public Health Service/NIH Objectivity in Research (1995; Amendments August 2012) |

|

| 2013 | Health Insurance Portability & Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Privacy Rule (Amendments January 2013) |

| 2013 | Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 (Amended 2007; 2013) |

|

NIH, Mitigating Risks of Life Science Dual Use Research Concern (2013) - US Government Policy for the Oversight of Life Science Dual Use Research of Concern (March 2012) |

|

|

Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), Increasing Access to the Results of Federally Funded Scientific Research (February 2013) |

|

|

Executive Order 13642 Making Open and Machine Readable the New Default for Government Information (May 2013) |

|

|

Defense/DFAR Safeguarding of Unclassified Controlled Technical Information (November 2013) |

|

| 2014 | The Digital Accountability and Transparency (DATA) Act (OMB; May 2014) |

|

National Institutes of Health, Genomic Data Sharing Policy (August 2014) |

|

|

OMB/COFAR Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards (December 2014) |

|

|

OSTP US Governmental Policy for Institutional Oversight of Life Sciences Dual Use Research of Concern (September 2014) |

|

|

Public Health Service, The Newborn Screening Saves Lives Reauthorization Act of 2014 (December 2014) |

SOURCE: Courtesy of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 2015. Based upon data collected by the Council on Governmental Relations. The list “lists federal regulatory changes that affect ‘the conduct and management of research under Federal grants and contracts’ in chronological order. In some instances, regulations were instituted and/or amended more than once; in these cases, all relevant changes were tallied. Also, when legislation required additional agency-based regulation, both the date of the legislation and the date of the agency regulation(s) were used. Regulations associated with the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 are not included.” See “Sustaining Discovery in Biological and Medical Sciences: A Discussion Framework,” Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 2015, accessed September 9, 2015, http://www.faseb.org/SustainingDiscovery/Home.aspx.

The costs of regulation may also be measured by administrative costs borne by research universities that are not reimbursed by funding agencies because of the 26 percent cap29 on the administrative component of F&A costs.

Some have sought to estimate the amount of time individual investigators divert from research to track information, gather administrative data, and prepare proposals and reports.30 As investigators typically receive research funding from multiple federal agencies, they and their administrative staff often spend unnecessary time, energy, and resources complying with agency rules, regulations, and policies that address common core issues and concerns but with different sets of requirements. As noted in the 2014 National Science Board report, “This overall lack of harmonization often comes at a high cost to investigators and institutions in the form of lost productivity and cost of administrative personnel.”31 This is a diversion not only of time and effort but also of expertise.

Others have recognized the opportunity costs associated with a potential decline in interest from future researchers, as students wary of a complex and adversarial regulatory environment pursue other careers.32 Opportunity costs also include foregone benefits from research that is not conducted while investigators spend time on regulatory compliance. Regardless of how the specific costs of compliance are computed, there are also the uncalculated costs as less time, expertise, resources, and potential is directed at the conduct of basic and translational research.

___________________

29The 26 percent cap on administrative costs refers to the amount of administrative costs associated with a particular project that can be reimbursed to a university.

30Sandra Schneider, Kristen Ness, Sara Rockwell, Kelly Shaver, and Randy Brutkiewicz, 2012 Faculty Workload Survey: Research Report, (Washington, DC: Federal Demonstration Partnership, 2014).

31National Science Foundation, Reducing Investigators’ Administrative Workload for Federally Funded Research, p. 16, (NSB-14-18) (Arlington, VA, 2014), http://nsf.gov/pubs/2014/nsb1418/nsb1418.pdf.

32Bruce Alberts, Marc W. Kirschner, Shirley Tilghman, and Harold Varmus, “Rescuing US Biomedical Research from its Systemic Flaws,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) 111, no. 16 (2014): 5773-5777.