6

An Assessment of the Early Accomplishments and Likely Long-Term Outcomes and Impacts of the Landscape Conservation Cooperatives Network

Congress asked the committee to assess “whether there have been measurable improvements in the health of fish, wildlife, and their habitats as a result of the program.” This chapter addresses this congressional request and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (FWS’s) charge to evaluate the following questions: What goals (and/or objectives) have been achieved? What improvements in managing and conserving habitats and fish and wildlife species might be reasonable to expect from the Landscape Conservation Cooperatives (LCCs) program in the timeframe it has existed? What longer-term impacts are likely to be realized?

The first section of the chapter provides examples of the goals and objectives that have been achieved so far. Given the youth of this program, the committee provides its explanation at the end of the chapter for why it is too soon to expect “measurable improvements in the health of fish, wildlife, and their habitats.” Consequently, the committee reviewed examples of other landscape-scale conservation programs to glean an indication of the long-term outcomes that can be reasonably expected from the LCCs. The committee also examined analyses that identify design and implementation features of landscape-scale conservation efforts that appear to be correlated with eventual success and applied these to the LCCs.

EARLY ACCOMPLISHMENTS OF THE LCCs AND THE LCC NETWORK

As discussed in Chapter 1, the geographic scope of the LCC Network includes much of North America and the Pacific and Caribbean Islands. Therefore, to achieve national coverage, the LCC program was designed as a network consisting of 22 regional, self-directed cooperatives. To develop such a network of LCCs, the individual LCC partnerships had to be put in place first.

The creation of these 22 LCCs is an early achievement and an important process outcome. They were evaluated as part of the Science Investment and Accountability Schedule (SIAS) Activity Area titled “organizational operations” (see Chapter 4). For all 22 individual LCCs, the following steps have been achieved:

- Appointed staff coordinators and science coordinators

- Appointed steering committees

- Developed the governance structure

- Convened the steering committees to develop a common set of goals and articulate the common vision and goals

- Initiated or completed the development of a strategic plan and science priorities

As a result of achieving these process outcomes, the coordinators have begun to make progress toward the means objectives articulated by the SIAS: (1) engagement and coordination, (2) leveraging resources, and (3) engaging the technical community and technical staff.

The task of assessing “measurable improvements in the health of fish, wildlife, and their habitats” as well as “what goals have been achieved” is difficult to assess for several reasons: (1) the LCCs do not have the authority to manage fish, wildlife, and habitats; (2) therefore, measuring improvements is not possible due to the difficulty in attributing results to collaborative, conservation efforts such as the LCCs; (3) assessing which objectives have been achieved at the national program level is difficult because the LCCs’ evaluation tool measures progress toward the Strategic Habitat Conservation Handbook (National Technical Assistance Team, 2008) goals and objectives instead of measuring progress toward the goals of the LCC Network Strategic Plan (hereafter referred to as the strategic plan; LCC, 2014); and (4) the LCC Network does not have an assessment tool or an effort to synthesize results from efforts across the network as a whole (see detailed description in Chapter 4).

Despite these challenges, the committee has attempted to describe some early progress by summarizing results from the individual LCC evaluations (i.e., results from the

SIAS assessments (see Chapter 4 for detailed descriptions). The committee provides some examples of other early accomplishments under each of the four strategic goal areas that correspond to the objectives listed in the strategic plan. Because the SIAS and the strategic plan are not aligned with regard to objectives and goals, the following should not be viewed as a formal, summative evaluation.

Goal 1: Conservation Strategy

Objective 1: “Identify shared conservation objectives, challenges, and opportunities to inform landscape conservation at continental, LCC, island, and regional scales.”

Almost all of the 22 LCCs have completed their strategic plans, and as such, have completed or initiated the identification and articulation of such shared conservation objectives. These plans appear to represent the shared objectives of the steering committee members of each LCC, assuming that each committee member was actively involved in the process. However, it is unclear how the broader stakeholder community was involved in the development of these shared objectives. The broad goals articulated by each LCC are consistent with and support the goals identified by the strategic plan. Based on these shared conservation objectives, the individual LCCs have funded projects jointly with their partners to guide how to address some of these conservation priorities. The SIAS results indicate that all of these strategic planning efforts have built on existing large-scale planning efforts, and some have effectively leveraged those existing efforts. For example, the Northwest Boreal LCC conducted a “comprehensive science and management information needs assessment.” This needs assessment included broad stakeholder outreach to “identify priorities, information gaps, and current/future planning efforts.” The LCC built its planning effort based on those results (SIAS NWB LCC FY 2014).

Objective 2: “Develop then deliver (through partners) regional landscape conservation goals and designs.”

Many important accomplishments can be listed for this objective. To date, the LCCs have funded 135 projects to conduct vulnerability assessments, and all LCCs have initiated the development of vulnerability assessments. Vulnerability assessments are a critical first step in adapting to the impacts of climate change (NRC, 2010; AFWA, 2012) and help resource managers identify priorities. Of the 22 LCCs, 4 report in their SIAS to have completed or adopted vulnerability or landscape assessments for 100 percent of the geography or 100 percent of the LCC’s priority resources, and 13 report to have completed or adopted vulnerability or landscape assessments for at least 66 percent of the geography or at least 66 percent of the LCC’s priority resources.

In addition, the LCCs have initiated 68 projects aimed to deliver conservation designs. Some LCCs have completed Landscape Conservation Designs (LCDs), such as the Conservation Blue Print for the South Atlantic, or the LCD in the Connecticut River Watershed (North Atlantic LCC). LCDs are defined in the strategic plan as: “[a]n iterative, collaborative, and holistic process that provides information, analytical tools, spatially explicit data, and best management practices to develop shared conservation strategies and to achieve jointly held conservation goals among partners.” How these plans are implemented will determine whether ends objectives can be accomplished (see Appendix C, guidance on Landscape Conservation Design). LCDs are important outputs to guide and improve resource management.

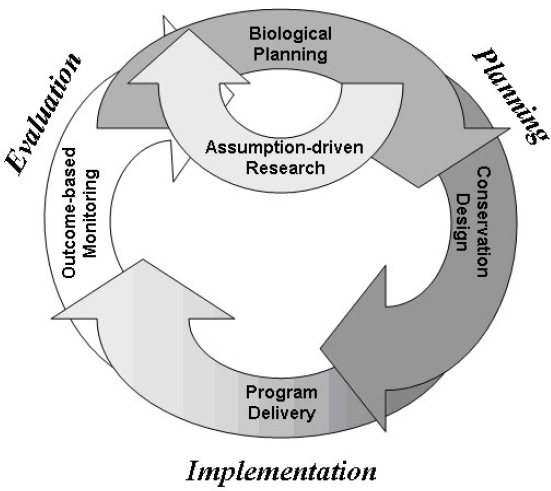

Because of the importance of the LCC’s LCD process to the LCC efforts, the committee reviews it in greater detail here. These LCDs are intended to “support resiliency and adaptation to both global change and regional landscape challenges, while ensuring the inclusion of all partners and stakeholders.” The FWS Strategic Habitat Conservation Framework has served as the conceptual foundation for Landscape Conservation Design and planning (National Technical Assistance Team, 2008), and the adaptive management cycle from that framework has helped inform both LCDs and adaptive management more broadly in LCCs (see Figure 6.1). The Conservation Measures Partnership’s Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation Version 3.0 (CMP, 2013) have also informed these designs (see South Atlantic LCC example below). The LCC Network Conservation Science Plan (LCC Science Coordinators Team, 2015) provides a step-by-step process for this planning and design, with the planning theme focused on establishing

SOURCE: National Technical Assistance Team, 2008.

targets (ecological features) and goals for these targets in the face of scenarios of future change. The design theme turns those objectives and targets into a spatial network of ecologically connected conservation areas, including a threat assessment and the translation of goals into resource management objectives. The planning theme is intended to include ecological processes, ecosystem services, cultural resources, and climate adaptation planning. LCC science coordinators are attempting to bring consistency and compatibility to conservation targets in regionally adjacent LCC units. Ultimately, there is a network goal of creating “seamless and compatible” Landscape Conservation Designs within LCCs that “collectively contribute to an ecologically connected network of functional landscapes and seascapes,” presumably across the United States.

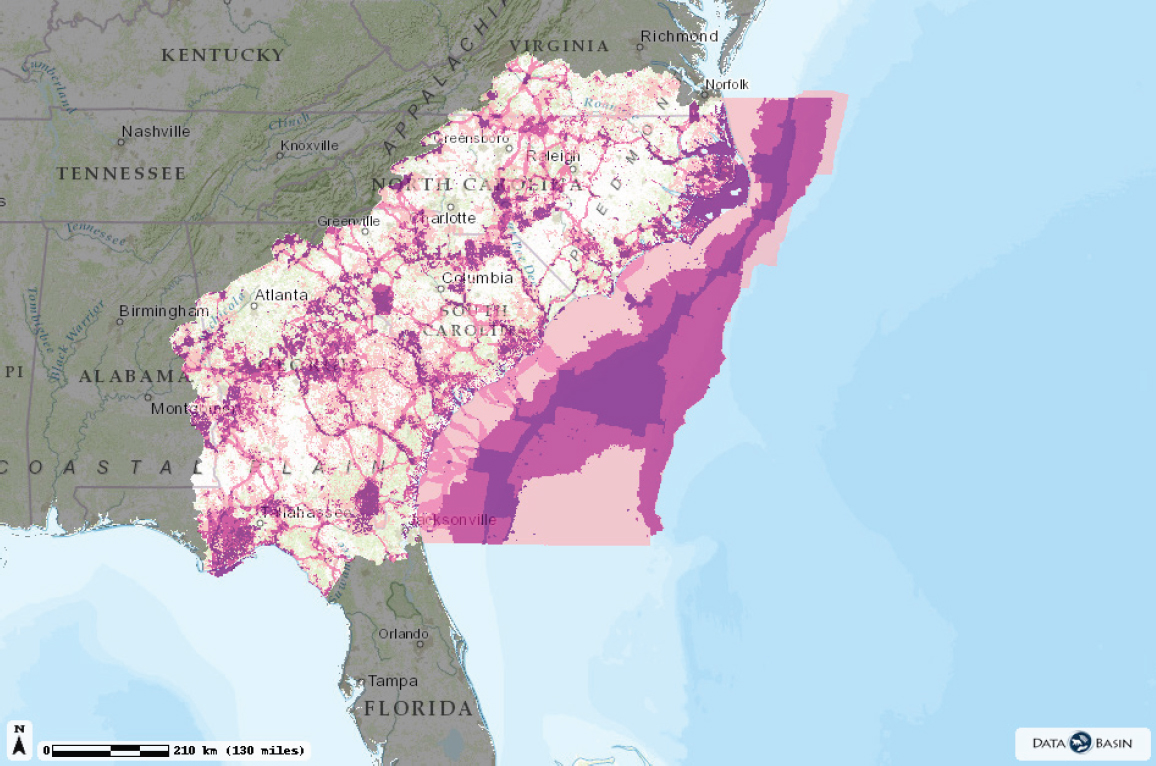

The most advanced of these is the Conservation Blueprint of the South Atlantic LCC, where version 2.0 was released in June 2015 (see Figure 6.2). More than 400 individuals from more than 100 organizations were involved in preparing the blueprint. It was developed through a series of regional workshops where participants selected small watersheds as priority conservation areas and then assigned various conservation actions to those watersheds based on a standard set of actions derived from the Open Standards for the Practice of Conservation (CMP, 2013). Numerous existing conservation plans were used to develop the priorities for the Conservation Blueprint, including but not limited to The Nature Conservancy’s Ecoregional Plans and several data sets that formed the basis for priority areas in State Wildlife Action Plans of the region. There is extensive documentation for how the map was prepared.1 Intended uses of the blueprint are: “finding places to pool resources, raising new conservation dollars, guiding infrastructure development, developing conservation incentives, showing how local actions fit into a larger strategy, and locating places to build resilience to major disasters.” Because of the coarseness of the data layers, the blueprint is not intended to be used for site-specific planning of conservation strategies and actions.

The North Atlantic LCC is also investing considerable effort in landscape conservation planning. Although it is not yet to the point of producing an LCD, its work grew out of the integrated planning efforts of the Northeast Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ Regional Conservation Needs Program (Terwilliger Consulting, 2013). This program essentially synthesized the State Wildlife Action Plans of 13 northeastern states for the purposes of addressing regional conservation priorities, bringing consistency to the planning efforts across the region, highlighting what is most important in terms of wildlife conservation for the region, and organizing data and information for future efforts. Like the South Atlantic LCC, the North Atlantic LCC is developing a Conservation Planning Atlas, and all of their data and map layers are available on a mapping platform powered by Data Basin.

Conclusion: In reviewing the guidance in the LCC Network Science Plan and the Conservation Blueprint of the South Atlantic LCC, the committee finds some shortcomings. Although the basic steps described in the LCC Network Science Plan are useful and parallel the conservation science and planning literature to some degree, they fall short in several important ways (of what planners, scientists, and practitioners will need in LCCs to develop adequate landscape conservation plans that can be implemented in a manner to achieve conservation outcomes) (Groves and Game, 2015).

First, the existing guidance primarily focuses on the spatial aspects of planning and gives limited attention to the strategies and actions that will be needed to conserve places identified in these blueprints. By integrating spatial planning (where should conservation areas be located) with strategic planning (what strategies do we advance to conserve places), conservation planners and practitioners can better set priorities.

Second, the existing guidance mostly emphasizes the identification of places to focus attention on conservation targets (species, ecosystems) when it is likely that the conservation plans and LCDs of LCCs in the future will need to focus on multiple objectives. These objectives include conservation targets, ecosystem services, cultural resources, and other social and economic objectives that the LCC stakeholders may want to achieve in concert. Marine spatial planning is a great example of a method of planning for multiple objectives.

Third, the existing guidance needs more attention on understanding the socio-ecological systems in which any LCC conservation plan or LCD is being conducted, with a greater understanding of the social systems being critical to long-term success of any broad-scale conservation plan.

Finally, all conservation plans and LCDs face risks and uncertainties, and are more likely to succeed if these risks and uncertainties are formally acknowledged and accounted for in the planning process. Because of the wealth of guidance available for how to prepare conservation plans and Landscape Conservation Design, the committee has summarized some important lessons from recent conservation planning peer-reviewed literature that could help improve the overall methodology of landscape conservation planning and design being advanced by the LCCs (see Appendix C).

Objective 3: “Integrate regional or other scale-specific conservation designs to align and focus conservation action at the network scale.”

As described in detail in Appendix B, the Mississippi River Basin/Gulf Hypoxia Initiative is an example of aligning LCCs to focus conservation planning and potential actions at the network scale. Another example of working across LCCs is the Gulf Coast Vulnerability Assessment, where four LCCs are jointly evaluating the vulnerability of coastal habitat to sea level rise. In fact, the SIAS results

___________________

1 See http://salcc.databasin.org/maps/a46404d870df478f871e1af23d8da539.

SOURCE: South Atlantic LCC, 2015.

indicate that all LCCs work with at least one other LCC and many report that “landscape-level conservation delivery has occurred as a direct result of” working across LCCs.

Goal 2: Collaborative Conservation

Objective 2: “Identify and explore opportunities for collaborative actions within the LCC Network.”

Several joint efforts that span multiple LCCs are in progress, such as the Mississippi River Basin/Gulf Hypoxia Initiative described in Appendix B and the effort to implement the Southeast Conservation Adaptation Strategy. All LCCs indicate in their SIAS that they collaborate with at least one other LCC, and the LCCs report to be “moderately or fully integrated” as part of the LCC Network. Thus, these results indicate progress has been made toward achieving this objective and work across boundaries. Although this goal highlights the LCC Network’s emphasis on collaborative conservation, it is unclear what framework and structure are in place to facilitate work across LCC boundaries. On the SIAS benchmark that assesses whether the individual LCCs view themselves as functioning as “part of [the] integrated network of LCC partnerships,” LCCs reported answers ranging from “moderately” to “fully.”

Objective 3: “Demonstrate, monitor, and evaluate the value and effectiveness of the LCC Network.”

Some early progress toward monitoring and evaluating the value and effectiveness of the LCCs and the LCC Network has been noted: the FWS developed an assessment tool—the SIAS—to evaluate the individual LCCs. However, as discussed in Chapter 4, the ability of “demonstrating effectiveness” of the program is severely hampered by lack of an effective process to monitor and evaluate progress toward the LCC Network-wide goals as outlined in the strategic plan. For a detailed description, see Chapter 4.

Goal 3: Science

Objective 1: “Identify shared science, information, and resource needs at the network scale.”

Although individual LCCs have identified science needs and funded research, at the network scale, progress toward this objective appears nascent. A network-wide LCC Science Plan is being developed and is nearing completion.

Objective 2: “Promote collaborative production of science and research—including human dimensions—as well as the use of experience and indigenous and traditional ecological knowledge among LCCs, Climate Science Centers (CSCs), and other interested parties; use these to inform resource management decisions, educate local communities, and address shared needs.”

As discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5, collaboration and coordination between LCCs and CSCs is uneven across the regions and will continue to be a critical need. LCCs have funded and produced science for up to 3 years, and examples can be cited where such research and tool development has contributed to management of resources. As described in detail in Appendix A, a joint project between an LCC and AFWA resulted in more strategic fire management. A process needs to be developed that ensures that coordination at the individual LCC/CSC level translates to effective coordination at the network level as well.

Objective 3: “Demonstrate and evaluate the value and improve the effectiveness of LCC science.”

A large number of projects have been funded or completed to deliver science for the LCCs and their partners.2 For example, 142 projects are listed under the “data acquisition and development” category, and 221 projects are listed under the “decision support” category. However, “demonstrating and evaluating” these individual projects at the LCC Network scale is challenging without an effective evaluation process. A few examples have been documented where LCC-funded research endeavors have improved conservation actions. For instance, the Appalachian LCC developed models and mapping tools to inform the “Assessing Future Energy Development Across the Appalachians” project. This plan was developed as a result of aforementioned research and intends to guide the balance between energy development and resource protection. Similarly, research funded by the Great Basin LCC is now enabling resource managers to more strategically allocate limited resources to battling wildfires that threaten critical sage-grouse habitat (Chambers et al., 2014).

Goal 4: Communications

Objective 1: “Communicate the existence and application of LCC Network science, products, and tools to partners and stakeholders in a form that is understandable, publicly accessible, engaging, and relates to what matters to end users and society.”

As identified during the most recent LCC Council meeting of March 26, 2015, communication is a critical objective and will be an ongoing effort. Examples have been documented of research and tools funded by individual LCCs to be communicated to stakeholders. For instance, the Aleutian and Bering Sea Islands LCC completed an analysis of major shipping routes in the Aleutian and the critical areas to avoid. This analysis and the areas to be avoided have been shared with the International Maritime Organization.

In summary, the above examples illustrate a range of early activities and accomplishments of the LCCs. This is not a comprehensive list and cannot do justice to the full range of accomplishments and milestones reached by the individual LCCs in the 4 years since the first LCCs were initiated. Yet, these examples indicate that diverse members of the LCC Network report progress in implementing key goals and objectives. It is beyond this study’s scope to summarize the extent and wealth of accomplishments captured in the 22 SIASs submitted by the individual LCCs, however.

Conclusion

Given the short time since the LCCs and the LCC Network were established, these are the types of process milestones that are reasonable to expect from the LCCs, which have the potential to improve management of fish and wildlife in the future. A few examples of the tools developed have already led to improved resource management (see Appendix A, case study on sage-grouse), but it would be unreasonable to expect many such outcomes at this point because science and tool development projects alone typically take 2 to 3 years to complete before conservation actions can be set. As previously discussed, an evaluation process needs to be developed that can capture and synthesize the accomplishments of the individual LCCs to provide a network-wide assessment of the achievements.

WHAT LONGER-TERM IMPACTS HAVE RESULTED FROM OTHER LANDSCAPE-SCALE EFFORTS?

To better understand what long-term impacts might be realized by the work of the LCCs, the committee reviewed evaluations and outcomes of other landscape-scale conservation initiatives with a longer history than the LCCs. These are provided to demonstrate the viability of the landscape-scale approach and to identify some of the components (means and processes) that characterize successful landscape-scale

___________________

efforts. Below, the committee discusses some accomplishments and key components of these apparently successful landscape approaches, but the committee cannot verify that there is a causal link between these components and the impacts. The committee anticipates that building a causal link between the collaborative, large-scale activities of the LCCs and concrete, positive impacts on biodiversity conservation will remain a difficult and elusive activity. The evaluations reviewed were for National Heritage Areas (NHAs), Pennsylvania Conservation Landscapes (PCLs), Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y), and the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture (ACJV). The first three examples were selected because we could draw from previous evaluations. The last effort was chosen because of the similarities to the LCCs (see Chapter 5 for more details on the similarity in program characteristics). Each of these initiatives was evaluated or reviewed using a different methodology and at different times in the program’s life cycle. However, each initiative discusses how progress toward stated goals was achieved and provides some analysis of the collaborative management practices that were important to success in working on a landscape scale.

Each initiative and its assessment are summarized below.

National Heritage Areas

NHAs reflect the nation’s significant and diverse heritage landscape. Forty-nine large landscape regions from Alabama to Alaska have been designated by Congress, ranging in size from smaller than a county to large bi-state regions. The first NHA was designated in 1984. The goals of NHAs are cultural and natural heritage conservation, interpretation, recreation, and community revitalization. Each area is locally managed, often by a coalition of partnership agencies and organizations with funding and technical support from the National Park Service (NPS). Each NHA has a management plan that sets forth the priorities for project implementation. Most receive federal operational funding and administer small grant programs.

The NPS undertook the evaluations of 12 of the long-established NHAs. These reviews could be characterized as summative evaluations examining the effectiveness and outcomes of the selected areas after 20 or more years of operation. In general, the evaluations reported positive findings. All but one of the NHAs addressed and made progress on each of the conservation goals identified in the area’s legislation and approved management plans. Based on a review of funding allocation directed to completed projects, the 12 NHAs focused on the goals of cultural and natural resource conservation (31 percent) and education and interpretation (26 percent); other work included recreational development and heritage tourism activities. The evaluations of this work stated that the individual NHAs had fulfilled or successfully fulfilled the area’s resource conservation goals. The evaluations also concluded that the work was carried out with a high level of partnership and citizen engagement. The evaluations documented the development of network management strategies and the ability to leverage funding for project development. Finally, the reviews noted the importance of continued NPS funding and support to the sustainability of the work (Barrett, 2013).

Pennsylvania Conservation Landscapes

The Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) has focused its efforts on seven regions in the state with significant public lands. The Conservation Landscape program’s goals are sustainability, conservation, community revitalization, and recreational development. DCNR provides substantial funding for operations and a regrant program. However, each of the seven initiatives is managed by a local steering committee with a dedicated staff person provided by one of the local partners. Local partners set the priorities for the landscape. The program was initiated in 2004.

DCNR undertook the evaluations of PCLs early in the development process after 5 years (formative evaluation) to improve and inform the direction of the program and to provide a possible justification for the program with a coming change in administration. The evaluation report concluded that partnership development of the two most mature PCLs showed significant progress in long-term stewardship of public lands and the development of a positive relationship with adjacent communities. The leadership and financial commitment of DCNR was found to be critical to the future success of the program (Patrizi et al., 2009). (Note: The program was continued by the next administration.)

Yellowstone to Yukon

Y2Y is a joint Canadian-U.S. initiative with the goal of preserving and maintaining the wildlife, native plants, wilderness, and natural process of the mountain ecosystem stretching more than 2,000 miles from Yellowstone National Park to the Yukon Territory. The Y2Y region includes two countries, five U.S. states, two Canadian provinces, two Canadian territories, the reservation or traditional lands of more than 30 Native governments, and a number of government land agencies. Y2Y offers science-based education and stewardship programs that encourage conservation of the area’s natural resources. Funding comes from a mix of public and private sources, and it was a challenge to find support in the early days of the project. This initiative was launched in 1994.

As part of the 20-year anniversary, a report titled The Yellowstone to Yukon Vision was prepared by the nonprofit organization that manages the overall project. The report summarizes the multiple habitat improvement projects between 1993 and 2013 as part of this large, transboundary effort. The report lists the strength of the network that implemented the Y2Y vision as an important component

that contributed to its success. However, it also noted the challenge of a nongovernmental organization in sustaining the project until it could show results.

Atlantic Coast Joint Venture

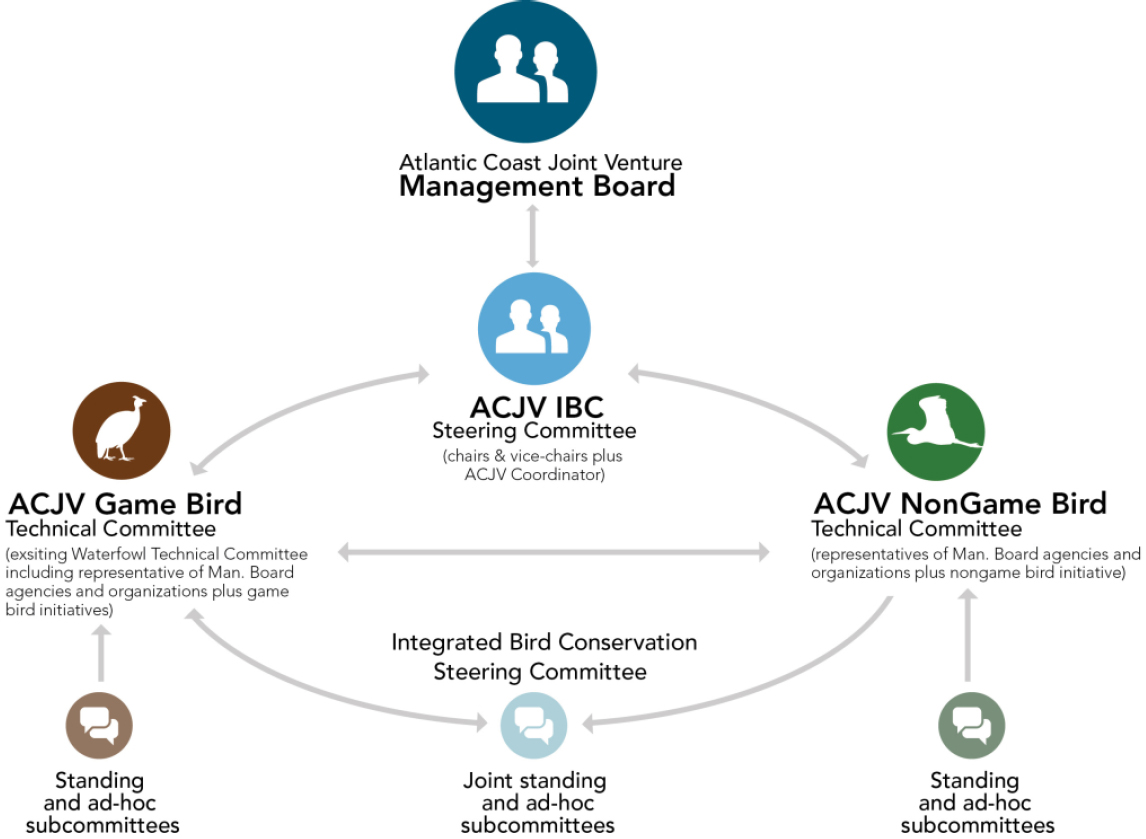

The ACJV is one of many Joint Ventures (see also Chapter 5); and it is focused on the conservation of habitat for the native birds of the Atlantic Flyway of the United States from Maine to South Florida. The ACJV was originally formed—as were others—as a regional partnership under the North American Waterfowl Management Plan (NAWMP) in 1988. This particular Joint Venture includes all the states along the Atlantic Coast and Puerto Rico, and partners from federal agencies (FWS, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, U.S. Geological Survey, and NPS), and nongovernmental organizations including American Bird Conservancy, Ducks Unlimited, The National Audubon Society, The Nature Conservancy, and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. The ACJV’s structure (see Figure 6.3) connects science with management through the formation of technical committees that inform particular initiatives. The steering committee coordinates the work of the various technical committees and the managing board develops, approves, and implements the ACJV’s implementation plan. The implementation occurs at a smaller scale either through state working groups or through focus area working groups. Partners in the ACJV are expected to contribute funds and activities that advance their jointly developed goals. Progress was measured primarily through the number of acres of habitat conserved.

The ACJV was not evaluated by external review, but the ACJV itself updated its strategic and implementation plans to include an assessment of progress made. Furthermore, the Joint Venture program as a whole was described by Giocomo et al. (2012). As of 2005, the ACJV had managed to conserve (through protection, restoration, and enhancement) almost 3 million acres of wetland since the inception of this Joint Venture in 1988. Future assessments and objectives will attempt to develop habitat conservation goals that are biologically linked to the breeding population goals.

SOURCE: http://acjv.org/about-us/acjv-structure.

In summary, there are significant differences in the goals and outcomes between the landscape-scale efforts of the NHAs and PCLs and the LCCs. NHAs, PCLs, and Y2Y take place at a smaller scale and in some cases are more focused on cultural conservation and community development goals. The Joint Venture program’s geographic focus is identical to that of the LCCs, having both continental-scale goals and a regional focus. However, in contrast to the LCCs, the ACJV works on more targeted species (i.e., migratory birds). Despite differences in intent, scale, and focus, there are similarities that may help inform the potential for long-term impacts of landscape-scale programs such as the LCCs. Specifically, LCCs are charged with the process of forming a network of partners to address issues on a landscape scale. For this reason, it may be useful to identify some of the components of landscape-scale projects and programs that can contribute to achieving programmatic goals.

COMPONENTS OF A LANDSCAPE-SCALE INITIATIVE IMPORTANT TO YIELDING DESIRED LONG-TERM OUTCOMES

It is challenging for the committee to address the statement of task question “What long-term impacts are likely to be realized?” because it is difficult to predict the future support for the LCC Network and individual LCCs, as well as many other factors that will determine whether the LCCs’ goals can be achieved. Thus, in this section the committee discusses a number of critical elements and processes that have been identified as important to the effectiveness of both the above examples and to the emerging field of large-landscape conservation.

Examining these components may be useful in projecting potential outcomes and successes of the LCCs. As discussed in Chapter 2, there is a substantial literature on landscape approach, conservation design, and collaborative governance; however, the literature evaluating collaborative governance and landscape-scale conservation practice is more limited. Recent publications have identified a continuum of approaches to working on regional collaborations and elements important to landscape-scale conservation (McKinney and Johnson, 2009; McKinney et al., 2010; Curtin 2015). Laven and others (Martin-Williams, 2007; Laven et al., 2010) have used data from NHA evaluations to explore the factors that have sustained the effectiveness of that program over time in a large-landscape setting. Curtin (2015) examines the underpinning of large-landscape work, including theories of collective impact, distributed cognition, and innovation and adaptation. Drawing from this work and the four case studies, the committee highlights some of the key components and how they are addressed as part of the LCCs.

A Unifying Theme or Story

A common vision solidifies the commitment of partnerships that have different perspectives. The vision can be based on either shared future desired state or shared problems. A common understanding provides stability in an inherently fragile system (Martin-Williams, 2007). This was identified as an important factor in operationalizing the NHAs serving as the “glue” that holds the areas together (Laven et al., 2010). In the Y2Y anniversary report, the vision for species conservation on a bi-national scale was identified as an important factor. It was the unprecedented big idea that garnered a great deal of support and momentum (Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, 2014). In the case of the Joint Ventures, the NAWMP and its central focus on waterfowl habitat protection provides the “glue” that allows the self-directed regional Joint Ventures to contribute in their own way to the common goal of conserving habitat, and it provides the central focus and boundaries around the scope of the work.

The stated purpose of the LCCs is responding to climate change and other landscape-scale stressors on land, water, and other natural and cultural resources, and this rationale could serve as the driver for the work of the individual LCCs.

Conclusion: This vision may be too broad and not as compelling as a place-based or species-based initiative, for example, the Y2Y’s objective to protect an indicator species such as the grizzly bear. Similarly, the Joint Ventures’ focus on waterfowl has provided them a central theme that helps justify the geographic boundaries and helps set priorities at a sub-regional level. However, the vision and goals of the individual LCCs might be more specific and defined by the partners. As a result, the priorities identified by the individual LCC steering committees might provide sufficient “glue” to compel collaborations.

Partnership and Network Development

Strong stakeholder engagement and an expanding network of partners is a critical element in large-landscape practice (McKinney et al., 2010). Evaluations determined that NHAs activated a network of partners from the national, state, and local sectors and that this network was a significant factor in the effectiveness of these regional efforts (Laven et al., 2010). In fact, some of the NHAs had more than 100 partners. NHA partnerships also promoted the development of an intergovernmental domain (Martin-Williams, 2007). Listening to the public and building trust and partnership relationships in the PCLs helped preserve resources and build social capital for the initiative (Patrizi et al., 2009). While there is no formal evaluation of the Joint Ventures’ network strength, Giocomo et al. (2012) refer to the Joint Ventures as a highly successful partnership for bird

conservation at a continental scale. During the information-gathering process for this study, comments from a number of stakeholders supported the view that Joint Ventures are a successful partnership. In the case of the ACJV, many partners of the management board have contributed to habitat conservation in significant ways. However, without a formal evaluation, it is not possible to determine whether these conservation actions were a direct result from the collaborative decision making as part of the management board or the ACJV steering committee.

LCCs were created explicitly using a partnership model to better integrate science and management, and to ensure an effective network in 22 regional landscapes. The steering committees for LCCs have members from federal, state, tribal, nongovernmental organizations, and other organizations, associations, or industries with an interest in landscape-scale conservation.

Conclusion: Although the design of the program indicates the intent to develop strong stakeholder engagement, as discussed in Chapter 4, it will require an assessment of the range of partners and the quality and functionality of these networks to indicate the potential for future success.

Adaptive Management

Adaptive management is important because a collaborative conservation approach needs to adapt to meet changing stakeholder needs (Barrett, 2013; see Chapter 2), as well as changing environmental threats. Learning from partnership development among the PCLs was an important strategy for the PCL program’s future (Patrizi et al., 2009). Giocomo et al. (2012) point to adaptive management as a central component of the Joint Ventures, which enables a seamless inclusion of science in resource management.

Conclusion: Monitoring the effectiveness of the LCC Network is a stated objective of the program. The strategies of the different LCCs to achieve their ends could be reviewed for how well they adjust to changing issues and respond to the needs of project partners.

Planning Documents

A key element in regional collaboration is a plan to move a project from vision to action (McKinney et al., 2010). For NHAs, their statutorily required management plans served as a roadmap for working at a landscape scale, and the goals in the NHAs’ plans were used as benchmarks to measure progress (Barrett, 2013). Joint Ventures addressed this important element by establishing a management board that oversees the development of an implementation plan (ACJV, 2005). The ACJV also supports the development of partnerships at the scale of the conservation deliverable that was identified through the ACJV, whether at the state level or at a smaller, more focused scale. There is a process in place that reduces broad continental-scale goals to a scale appropriate for conservation delivery, based on a solid biological foundation (ACJV, 2009).

One of the purposes of the LCCs is to develop shared landscape-level conservation objectives. Each of the LCCs has established an initial mission and strategic plan for its region. At this point, it is unclear how they will move from these high-level strategic plans toward implementation of conservation activities, as well as what authority or financial capacity LCCs have to advance their vision. In the future, these strategic plans and associated implementation plans will be important for evaluating and measuring progress, as discussed in greater details in Chapter 4. Although LCCs do not have direct management authority, many of the partners on the steering committee do have such authority.

Conclusion: Moving beyond planning toward conservation delivery will depend on the LCCs’ catalyzing such conservation actions by their steering committee members with such management authority.

Aggregating Project Impact

The aggregation of data into similar categories from the 12 NHA evaluations, using expenditures, financial leverage, and project completion, demonstrated the impact of the initiative (Barrett, 2013). For example, the Y2Y has produced a report that sums the increase in areas with protected designation within the project’s landscape. The PCLs used total acres acquired (in total 66,000 acres were acquired between 2003 and 2008) to measure and aggregate the program’s impact. The ACJV’s updates on its strategic plan (ACJV, 2009) and its implementation plan (ACJV, 2005) include an assessment on how the partners have contributed to conservation of wetlands.

As discussed in the previous chapter, the LCCs could use the information collected for the individual 22 LCCs in aggregation to track progress in categories such as climate adaptation or objectives that address projects such as sage-grouse habitat or Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico hypoxia (see Appendix B). Further details on the evaluation process are discussed in Chapter 4. However, as discussed in Chapter 4, the existing evaluation process does not enable easy aggregation of project impacts.

Conclusion: As discussed in Chapter 4, the ability of the LCC Network to demonstrate its overall impact would be greatly enhanced with better synthesis and aggregation of individual LCCs progress.

Significance of Leverage

This information can be used to show progress toward project goals in a more cost-effective manner (Barrett, 2013). NHAs were successful in leveraging funding and exceeded their 50 percent matching goal. The program managed to leverage funding for heritage infrastructure up to a 4:1 ratio (Barrett, 2013). The Y2Y anniversary report shows growth of the network and the power of leveraging support to achieving conservation outcomes such as habitat protection. The Joint Ventures’ main program website states that “[o]ver the course of [the program’s] history, Joint Venture partnerships have leveraged every dollar of Congressional funds 34:1 to help conserve 22 million acres of essential habitat for birds and other wildlife.”

The LCCs’ SIAS is tracking the leveraging support from regional parties as a proxy measure to demonstrate the strength of the partnership, as well as to show the program’s impacts or ends achieved by working in partnerships (see additional details in Chapter 4). So far, most LCCs report the leveraging at greater than 67 percent. Because the LCCs themselves have only limited implementation authority and rely mainly on the participating partner organizations for implementing their strategic plans, tracking on-the-ground conservation actions as part of leveraging will be important to demonstrate progress. Given that they use a partnership model very similar to the Joint Ventures, it is likely that the LCCs would leverage their resources at a relatively high rate.

Role of Governmental Agencies

NPS—by convening and funding NHAs—played a critical role in providing the environment that fostered a broad coalition across many organizations. In this way, the agency furthered its goals to create a partnership to conserve nationally significant resources (Martin-Williams, 2007). The hands-on leadership of Pennsylvania’s DCNR was an essential factor in the success of the Pennsylvania Conservation Landscape (Patrizi et al., 2009). There is evidence that if NPS withdraws support from NHAs, the program will be severely diminished or will not survive (Alliance of National Heritage Areas, 2013). As discussed in Chapter 5, the North American Waterfowl Management Plan preceded the Joint Ventures, which were established to implement the North American Waterfowl Management Plan. Congress supported the North American Waterfowl Management Plan by passing the North American Wetlands Conservation Act in 1988. This statute was reauthorized in 2002 and 2006 with expansions to include all habitats and birds associated with wetlands and funds up to $75 million per year. This support plays an important role in bringing partners together and providing the Joint Ventures with the financial resources to accomplish their goals.

The U.S. Department of the Interior authorized the creation of the LCCs with Secretarial Order No. 3289 (see Chapter 1 and Appendix E), which provides operating funds and grants and serves as a platform for interagency cooperation. Funding is administered through the FWS regional offices. As a result, LCCs are perceived by some as competing for funds available to other FWS programs. The agency and the FWS regional offices’ continued support, including funding, will be an important signal to the partners about long-term viability.

CONCLUSIONS

Early Accomplishments

At this point, it is too early to expect “measurable improvements in the health of fish, wildlife, and their habitats” for three reasons. First, the LCCs do not have the authority to deliver conservation, but instead work to accomplish the goal of improved management through partners. It requires time to develop partnerships, to establish shared goals, and eventually for partners with the authority for conservation delivery to implement those goals. Only at that point can one expect to begin to see improvements in the health of target species or habitats.

Second, in addition to the time lag between program inception and conservation improvements on the ground, it will be difficult to measure these improvements. In the case of collaborative conservation, it will be difficult to apportion credit for how the LCCs or the many individual partners have contributed to a given outcome (see Appendix A, case study on sage-grouse, and discussion in Chapter 4 about metrics). Our examples of similar programs demonstrate that this linkage can be established, but the value-added of the convener is difficult to quantify or attribute.

Third, the LCC Network has not yet developed a process to aggregate accomplishments of the individual LCCs to a network-wide programmatic assessment.

Nevertheless, the committee found many early accomplishments for almost all of the 19 objectives, such as the identification of shared conservation objectives, vulnerability assessments on a large number of resources across the United States, development of Landscape Conservation Designs, and production and delivery of many research projects, as discussed in detail above. In fact, some tools and research results funded by individual LCCs have already been noted as improving resource management decisions (see Appendix A). These early accomplishments are in line with the types of process objectives the committee would expect to see achieved during the early inception phase of a new federal program of this scale.

Likely Long-Term Outcomes

The LCC Network is a young program with an ambitious set of goals. Delivering on such broad and ambitious goals will require that the individual, self-directed LCCs succeed at setting strategic priorities and identifying conservation deliv-

erables, as well as at establishing a process that can result in the desired improvements in managing natural and cultural resources. As discussed in Chapters 1 and 2, the threats and challenges to the nation’s natural and cultural resources require a landscape-scale approach to conservation, and it appears from the committee’s review in Chapter 5 that no other federal program is in a position to meet this need.

As outlined above, important lessons can be learned from other landscape conservation programs that have existed much longer. Critical components that are important for such collaborative efforts include a unifying theme, strong stakeholder engagement, adaptive management, strategic planning efforts, metrics to aggregate project impacts, leveraging, and a lead agency that provides resources and leadership. Based on the discussion above, the LCCs have most of these components in place. As discussed in Chapter 3, the overall LCC Network’s goals, structure, and functions are consistent with the landscape approach, including the components outlined above, and therefore it should be in a position to deliver on its long-term goal of improving cultural and natural resource management. However, a firm financial commitment seems essential to sustaining the LCCs.

If sustained and successful, the LCCs will provide a process by which stakeholders can engage at the landscape scale to set strategic conservation priorities that can span interest groups and narrow disciplinary or sectoral approaches. It will also provide an important body of knowledge and tools to improve resource management. However, the committee concludes that it would require the LCCs to develop a process that can account and track how their planning efforts result in the implementation of on-the-ground conservation. In previous chapters, the committee has provided specific recommendations that would further improve the ability of the LCC Network to deliver its vision of “[l]andscapes capable of sustaining natural and cultural resources for current and future generations.” In summary, the committee concludes that the LCC Network has the required elements to contribute and add value to the nation’s conservation challenge at the landscape scale.

This page intentionally left blank.