7

Promotion, Motivation, and Support of Breastfeeding with the WIC Food Packages

Promotion of breastfeeding is a primary goal of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), in alignment with the Healthy People 2020 target of 82 percent of infants being ever-breastfed by the year 2020 (HHS, 2015). The WIC food packages are designed to accommodate both full and partial breastfeeding (varying widely in proportions of human milk and formula consumption), with the full breastfeeding package containing proportionately more food for the mother and less for the infant. This chapter examines the health benefits of breastfeeding for mothers and infants, breastfeeding trends in the United States and in WIC populations, barriers and incentives to breastfeeding in the WIC population, and factors associated with breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity. The information presented here was collected from the committee’s literature review, which was described in Chapter 3.

BREASTFEEDING AND THE WIC PROGRAM

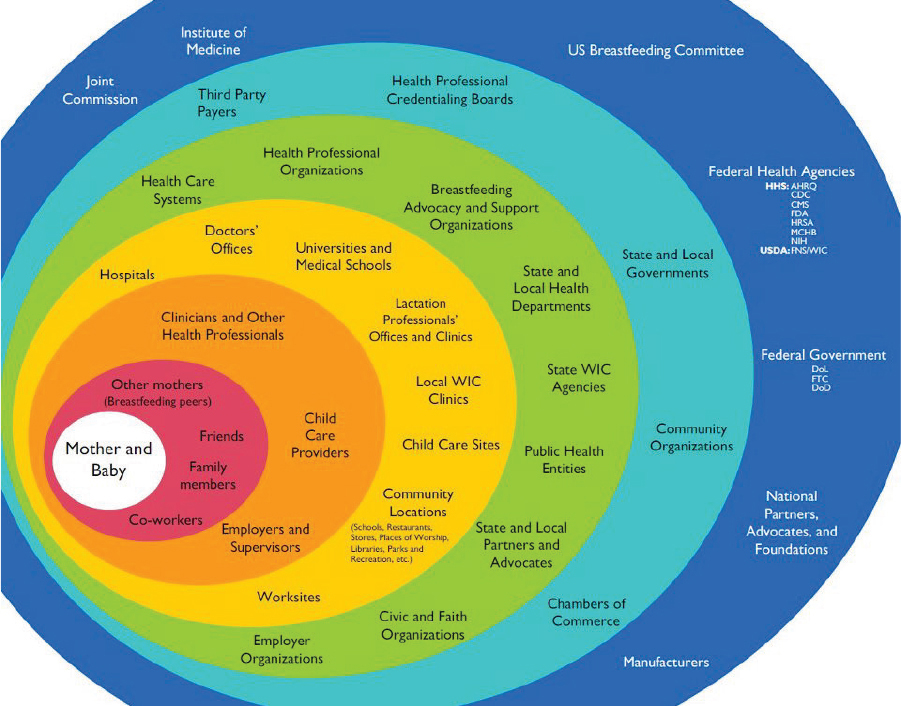

Breastfeeding is a complex behavior determined by multiple layers of socioecological factors, ranging from federal and state policies to lactation management support (see Figure 7-1). Given that WIC provides support for over half of all U.S. births, the WIC program plays a key role in influencing infant feeding decisions, particularly among low-income women. In fact, more than any other entity, WIC comes closest to having a nationwide coordinated breastfeeding program in place. At the same time, paradoxically, the WIC program engages heavily in the distribution of infant formula. WIC infant formula accounted for between 57 and 68 percent of all

SOURCE: Grummer-Strawn, 2011.

formula sold in the United States in 2004–2006 (the most recent years for which a published estimate was available) (USDA/ERS, 2010).

WIC program activities intended to increase breastfeeding prevalence parallel the three categories of global strategies known to improve breastfeeding outcomes (protection, promotion, and support)1:

- WIC breastfeeding protection activities include not providing infant formula during the first month after birth to mothers who have expressed their desire to breastfeed.

- WIC breastfeeding promotion activities include enhanced WIC food packages; counseling on maternal–child health benefits offered by

__________________

1 Effective global strategies to improve breastfeeding outcomes include protection (e.g., enforcement of the World Health Organization Code for the Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes, labor legislation to support the needs of employed women), promotion (e.g., mass media campaigns, World Breastfeeding Week), and support activities (e.g., the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative, breastfeeding peer-counseling programs) (Pérez-Escamilla and Chapman, 2012; Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2012).

-

WIC; and posters, brochures, and other materials posted at WIC clinics or offered to mothers to take home with them.

- WIC breastfeeding support activities include the WIC breastfeeding peer-counseling program, lactation management support offered by certified lactation consultants hired by the program (i.e., certified by the International Lactation Consultant Association), and the provision of breast pumps to women.2

WIC has been actively protecting, promoting, and supporting breastfeeding since 1989, when Congress enacted the first of a series of laws affecting WIC breastfeeding activities. In 1989, WIC was required to develop standards to ensure adequate breastfeeding promotion and support at both state and local levels (USDA/FNS, 2013). In 1992, Congress required that the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) establish a national breastfeeding-promotion program and provided various means by which this could be funded. Two years later, Congress passed the Healthy Meals for Healthy Americans Act, not only requiring that state WIC agencies spend $21 for each pregnant and breastfeeding woman in support of breastfeeding promotion, but also that state agencies collect (and report every 2 years) data on the incidence and duration of breastfeeding among WIC participants.3 In 1998, the 105th Congress authorized WIC agencies to use food funds for the purchase or rental of breast pumps.4

BENEFITS OF BREASTFEEDING

It is widely accepted that breastfeeding is beneficial for both mother and infant (AAP, 2014). An abundant literature documents short-term benefits of human milk for infants in particular. In infants, beyond the essential nutritional value, human milk contains numerous protective factors that help prevent infectious disease (Gertosio et al., 2015). But the long-term effects for both infants and mothers are less well studied. This section summarizes available data on the long-term health benefits of breastfeeding in infants and mothers, with a focus on data specifically relevant to the WIC population.

Given that it is unethical to assign infants at random to be breastfed or not, the committee recognized that most of the studies in which the effects of breastfeeding on health outcomes of the mother and her child have been

__________________

2 While these are common support activities, they are not available universally among WIC state agencies.

3 103rd Congress. 1994. Public Law 103-448: Healthy Meals for Healthy Americans Act.

4 105th Congress. 1998. Public Law 105-336: The William F. Goodling Child Nutrition Reauthorization Act.

evaluated are observational. They therefore have the well-known weaknesses characteristic of these types of studies. In particular, these studies are not suitable for causal inference. In addition, interpretation of the findings summarized here is limited by the variability across studies and among subjects in duration and intensity of breastfeeding. However, there is strong biological plausibility for an association between breastfeeding and several, but not all, infant health outcomes studied as well as some maternal health outcomes.

Although several recent studies suggest that association of breastfeeding with health outcomes including weight or obesity (Cope and Allison, 2008; Smithers et al., 2015) or cognition (Colen and Ramey, 2014; Jenkins and Foster, 2015) are not significant, a large body of evidence supports these associations (Horta et al., 2015a,b).

Infant Benefits of Breastfeeding

The World Health Organization (WHO) (2013) systematic review of the literature reported several long-term health benefits associated with breastfeeding, including decreased risk of obesity, particularly in high-income countries. Additionally, infants who are primarily breastfed have been shown to be at lower risk for type 2 diabetes, although the association is not necessarily causal and may be related to the lower incidence of childhood obesity among breastfed infants (Ip et al., 2007; WHO, 2013; Horta et al., 2015a). Additional evidence suggests that breastfeeding is associated with lower systolic blood pressure, but not with cholesterol concentrations or the incidence of cardiovascular disease (WHO, 2013; Aguilar Cordero et al., 2015). Breastfeeding is associated with a lower risk for many other health complications as well, including childhood leukemia, non-specific gastroenteritis, severe lower respiratory tract infections, sudden infant death syndrome, and atopic dermatitis (Ip et al., 2007; Amitay and Keinan-Boker, 2015). Additionally, breastfed infants may have increased protection from asthma later in childhood (Lodge et al., 2015). Finally, Tham et al. (2015) reported that breastfeeding for up to 12 months may be protective against the development of early childhood dental caries, but data were inconclusive for such an association after 12 months of age.

Available data regarding cognitive outcomes for breastfed infants are mixed (Ip et al., 2007; WHO, 2013). In a recent systematic review, Horta et al. (2015b) reported that breastfeeding was positively associated with intelligence test outcomes as late as 19 years of age, after adjusting for maternal intelligence. Meta-regression performed as part of this meta-analysis confirmed that the association between breastfeeding and intelligence remained when only the studies with the strongest research designs were included. The strength of the evidence varies for each of the associa-

tions described above, and is strongest for reduced obesity, type 2 diabetes, and childhood leukemia. (Chapter 6 summarizes additional evidence on cognitive outcomes associated with infant nutrition, although not breastfeeding specifically.) The mechanisms underlying these associations remain to be elucidated.

Maternal Benefits of Breastfeeding

Although not as frequently studied as infant outcomes, breastfeeding is also associated with positive maternal health outcomes. In their systematic review, Ip et al. (2007) reported that breastfeeding was associated with decreased risks for type 2 diabetes and ovarian and breast cancer; this association was recently confirmed by Chowdhury et al. (2015). Additionally, Chowdhury et al. (2015) reported finding some evidence to suggest that shorter duration of breastfeeding is associated with higher risk of postpartum depression, although the direction of causation was unclear. Lastly, they found no evidence to suggest an association of breastfeeding with osteoporosis (Ip et al., 2007). In their recent review, Chowdhury et al. (2015) also found that breastfeeding was associated with a reduced risk of maternal type 2 diabetes but did not detect a relationship between breastfeeding and maternal depression, bone mineral density, or postpartum weight change. Recently, Gunderson et al. (2015) published findings from a large prospective cohort study in which longer breastfeeding duration was associated with lower carotid intima-media thickness (a marker for cardiovascular disease risk) (Gunderson et al., 2015).

The association between breastfeeding and postpartum weight retention is more complex than for these other outcomes, because both breastfeeding duration and postpartum weight are affected by pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and gestational weight gain; the role of these factors has not been considered in many published studies. As a result, except for the two WIC-specific studies mentioned below (Krause et al., 2010; Østbye et al., 2010), the committee found variable evidence supporting a relationship between breastfeeding and postpartum weight loss.

Breastfeeding and Health Outcomes in the WIC Population

The committee identified only 10 studies in which the associations between breastfeeding and health outcomes had been examined in the WIC population (Dennison et al., 2006; Reifsnider and Ritsema, 2008; Maalouf-Manasseh et al., 2011; Barroso et al., 2012; Davis et al., 2012, 2014; Lindberg et al., 2012; Anderson et al., 2014; Edmunds et al., 2014; Shearrer et al., 2015). All of these studies used an observational design. The most prominent trend among these studies was a lower risk for childhood obesity

among infants who were breastfed for at least 4 months (see Appendix S, Figure S-1). However, there was no statistically significant difference in child weight comparing those who were exclusively or partially breastfed. A single study showed that children who were breastfed for more than 6 months had lower odds of rapid infant weight gain (Edmunds et al., 2014).

In addition to weight status, another primary focus of many of these WIC-focused studies was iron status. However, small sample sizes and heterogeneity in iron status measures, analytical approaches, and age ranges of the children studied make it difficult to draw conclusions about the relationship between breastfeeding and iron status among WIC children.

For maternal health outcomes, the committee identified two studies that reported less maternal weight retention in mothers who breastfed their infants for more than 20 weeks (Krause et al., 2010; Østbye et al., 2010). These results suggest that longer breastfeeding duration is associated with lower postpartum weight retention.

BREASTFEEDING TRENDS IN THE UNITED STATES AND THE WIC POPULATION

Breastfeeding Trends in the U.S. Population

Healthy People 2020’s goals for breastfeeding are presented in Table 7-1 (HHS, 2015). In 2011, the U.S. Surgeon General called for action to support these goals, recommending that families, communities, health care centers, and employment sites provide the support necessary to initiate and continue breastfeeding (HHS, 2011). To assess progress toward reaching these goals, in 2014 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

TABLE 7-1 Healthy People 2020 Breastfeeding Objectives Compared to 2014 Proportion (%) of Children Who Were Breastfed at Various Ages

| Breastfeeding Behavior and Infant Age | Healthy People 2020: Objectives | 2014 U.S. Breastfeeding Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion who ever breastfed | 81.9 | 79 |

| Proportion breastfeeding at 6 months | 60.6 | 49 |

| Proportion breastfeeding at 1 year | 34.1 | 27 |

| Proportion exclusively breastfeeding at 3 months | 46.2 | NA |

| Proportion exclusively breastfeeding at 6 months | 25.5 | NA |

NOTE: NA = Not available.

estimated breastfeeding prevalence across the United States using data from the 2012 and 2013 U.S. National Immunization Surveys (on children born in 2011). These estimates are also presented in Table 7-1.

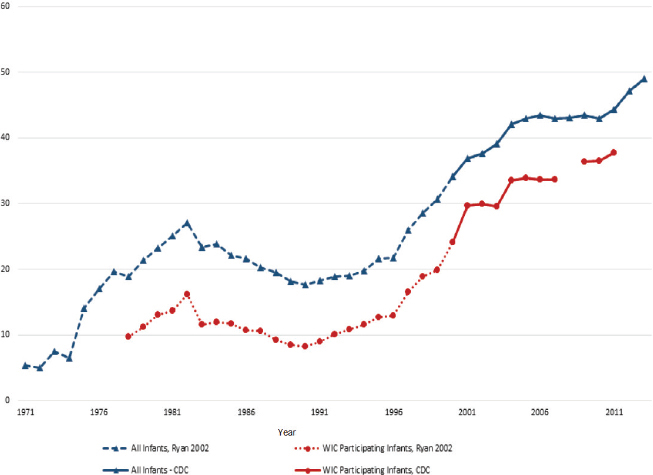

Although the national goal for initiation of breastfeeding has nearly been achieved, goals for duration of breastfeeding have been more challenging to meet (CDC, 2014a). This may result, in part, from differences in breastfeeding behavior related to racial and ethnic groups, maternal education and age, and WIC participation (CDC, 2010). Trends in breastfeeding prevalence for 6-month-olds for all U.S. infants (1971–2013) and for WIC infants (1978–2011) are illustrated in Figure 7-2 (Ryan et al., 2002; CDC, 2015).

NOTES: Data exclusively for non-WIC participants was not available. Therefore, the comparison of all infants to WIC infants is an underestimate of the difference of interest, namely non-WIC versus WIC infants.

Two data sources were used to construct this time series: the Ross Laboratories Mothers Survey (Ryan et al., 2002) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2015). The Ross Laboratories Mothers Survey is a large national survey conducted by Ross Laboratories, a manufacturer of infant formula. Ross sent questionnaires each month to a sample of mothers. Nearly 1 million surveys were sent annually in the 1990s (Ryan, 2005). For example, in 1996, 744,000 questionnaires were mailed (Ryan et al., 2002). Data for 1971 to 1999 are from Ross Mothers Survey.

SOURCES: Ryan et al., 2002; CDC, 2015.

Breastfeeding Trends in the WIC Population

Since the food package revision in 2009, there has been a concerted effort within WIC to increase the proportion of women who breastfeed. Although other measures of breastfeeding prevalence were available to the committee, the longest time-series for which all-infant and WIC-infant prevalence of breastfeeding at 6 months of age could be compared is presented in Figure 7-2. In 2013, the all-infant 6-month breastfeeding prevalence was 49 percent, while the WIC-infant estimate was 38 percent. Although a lower proportion of WIC infants were breastfed than those in the general population, the prevalence of breastfeeding in both groups has been increasing since the late 1970s.

From 2008 to 2011, 6-month breastfeeding prevalence in the United States has consistently tracked with income, being as low as 33 to 38 percent for women under 100 percent of the poverty level to as high as 60 to 68 percent in women at 600 percent or more of the poverty level (see Table 7-2). Although breastfeeding increased between 2008 and 2011 for women in all income levels by about 13 percent, increases were highest among women with the highest incomes. The most recent WIC Participant and Program Characteristics (PC2012) report, indicated that 67 percent of infants (being served by agencies that provided data) were ever breastfed in 2012 (USDA/FNS, 2013). Other available data indicate that between 2004 and 2008, breastfeeding prevalence was lower for WIC women compared to non-WIC, low-income women (CDC, 2010).

A number of breastfeeding promotion and support strategies have been in place as part of Healthy People 2020 that may have helped to increase the prevalence of breastfeeding in both WIC and non-WIC populations. Goals related to promotion include increasing the proportion of employers that have worksite lactation support programs, reducing the proportion

TABLE 7-2 6-Month Breastfeeding Prevalence (%), by Income from 2008–2011

| Income Relative to Poverty Level | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 100% | 33.5 | 35.7 | 38.1 | 37.8 |

| 100–199% | 41.3 | 44.7 | 42.5 | 45.5 |

| 200–399% | 50.0 | 53.4 | 55.1 | 57.7 |

| 400–599% | 55.1 | 61.1 | 59.3 | 61.9 |

| 600% or greater | 60.2 | 61.7 | 65.4 | 67.9 |

SOURCE: National Immunization Survey Data, as analyzed by the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Healthy People 2020 (HHS/CDC, 2015).

of breastfed newborns who receive formula supplementation within the first 2 days of life, and increasing the proportion of live births that occur in facilities that provide recommended care for lactating mothers and their babies (HHS, 2015). The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative has been assisting hospitals with meeting these goals (IOM, 2011; WHO, 2012).

BARRIERS, MOTIVATORS, AND INCENTIVES TO BREASTFEEDING IN THE WIC POPULATION

As part of its literature search, the committee looked for evidence on barriers, motivators, and incentives to breastfeeding in the WIC population. Key findings from this search are summarized in Table 7-3 and described below. Some additional searches were conducted in low-income populations in general, or to identify barriers among specific cultural groups. Breastfeeding is influenced by a complex web of interrelated systems operating at different levels of the socioecological model (Pérez-Escamilla and Chapman, 2012). During its evaluation, the committee recognized these many different layers of influence surrounding WIC mothers that affect their ability to breastfeed successfully (see Figure 7-1), including the role of the health care system.

Social and Cultural Factors Associated with Breastfeeding in WIC Women

Studies show that low-income women are less likely to initiate and sustain breastfeeding compared to their higher-income counterparts. Moreover, even in studies that specifically target low-income women, women who participate in WIC have lower breastfeeding initiation rates and shorter breastfeeding duration than those who are not enrolled in the program (Jensen, 2012; also see Table 7-4). A number of social, cultural, and structural barriers to breastfeeding in the WIC population have been reported, including the lack of prenatal, perinatal, and postpartum breastfeeding support (e.g., support from health care providers, family members, and partners); the need to return to work and lack of access to breast pumps, time, and inadequate pumping facilities at worksites; lack of child care; social norms regarding breastfeeding in public; and promotion of a sexualized body image in western society (Hurst, 2007; Heinig et al., 2009; Mickens et al., 2009; Stolzer, 2010; Wojcicki et al., 2010; Shim et al., 2012; Hedberg, 2013; Spencer et al., 2015).

Additionally, one topic that has been widely discussed among researchers, advocates, and other WIC stakeholders has been the provision of formula in WIC. Research suggests that the availability of formula may contribute to lower breastfeeding adoption and duration in women enrolled

TABLE 7-3 Barriers and Incentives to Breastfeeding in WIC Populations

| Barrier | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| Support | Lack of prenatal support | Hedberg, 2013a |

| Tenfelde et al., 2011b | ||

| Lack of support in hospital | Varela et al., 2011 | |

| Lack of social support (partner, family, social network) | Hurst, 2007b | |

| Varela et al., 2011 | ||

| Wojcicki et al., 2010b | ||

| Heinig et al., 2009 | ||

| Spencer et al., 2015 | ||

| Lack of professional support | Hurst, 2007b | |

| Varela et al., 2011 | ||

| Lack of knowledge | Varela et al., 2011 | |

| Lack of access to breast pumps | Holmes et al., 2009 | |

| Time | Return to work or school, unsupportive workplace, time away from baby | Hedberg, 2013a |

| Holmes et al., 2009 | ||

| Hurst, 2007b | ||

| Stolzer, 2010 | ||

| USDA/FNS, 2012b | ||

| Tenfelde et al., 2013b | ||

| Provision of formula | Formula from WIC valued over expanded food package | Hedberg, 2013a |

| Formula supplementation in hospital | Holmes et al., 2009 | |

| Tender et al., 2009b | ||

| Psychosocial | Belief that formula and solids are unavoidable in certain situations | Heinig et al., 2006 |

| Belief that providers would not understand family’s circumstances | Heinig et al., 2006 | |

| Impact of BF on body and sexuality | Johnston-Robledo and Fred, 2008b | |

| Varela et al., 2011 | ||

| Culturally constructed belief systems, e.g., African American | Ma and Magnus, 2012b | |

| Stolzer, 2010 | ||

| Hedberg, 2013a | ||

| Varela et al., 2011 | ||

| Embarrassment/discomfort nursing in public | Holmes et al., 2009 | |

| Hurst, 2007b | ||

| Johnston-Robledo and Fred, 2008b | ||

| Wojcicki et al., 2010b |

| Barrier | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of insufficient milk (PIM) | USDA/FNS, 2012b | |

| Tenfelde et al., 2013b | ||

| Fear | Hedberg, 2013a | |

| Dislike BF | USDA/FNS, 2012b | |

| Relatives, not parents, caring for child | Shim et al., 2012b | |

| Wojcicki et al., 2010b | ||

| Physical | Mother became sick | USDA/FNS, 2012b |

| Physical discomfort and difficulty | Hedberg, 2013a | |

| USDA/FNS, 2012b | ||

| Wojcicki et al., 2010b | ||

| Varela et al., 2011 | ||

| Tenfelde et al., 2013b | ||

| Incentive | Reference | |

| Support | Professional advice delivered with empathy, confidence, respect, and calm | Heinig et al., 2009 |

| Support groups, group classes | Mickens et al., 2009b | |

| Varela et al., 2011 | ||

| Tender et al., 2009b | ||

| Clear and effective BF education from WIC | Murimi et al., 2010b | |

| Individual consultation, peer counseling | Varela et al., 2011 | |

| BF initiation and BF education in hospital | Ma and Magnus, 2012b | |

| Psychosocial | Belief that BF is beneficial | Vaaler et al., 2010b |

| Heinig et al., 2006 | ||

| Culturally constructed belief systems, e.g., Hispanic | Wojcicki et al., 2010b | |

| BF costs less than formula | Wojcicki et al., 2010b |

NOTES: BF = breastfeeding. References lacking a symbol are qualitative in nature.

a Systematic review.

b Observational study.

in the program (Varela et al., 2011; Hedberg, 2013). However, as noted by Jiang et al. (2010), a major challenge to measuring the causal effect of WIC on breastfeeding (and the causal effects of WIC on many outcomes, as described in Chapter 3) is the issue of selective enrollment. WIC participants tend to be more socioeconomically disadvantaged than eligible nonparticipants, which may partially explain their lower tendency to breastfeed

TABLE 7-4 Association Between WIC Participation and Breastfeeding Outcomes: Summary of Evidence

| Author, Year Location | Study Design (N) | BF Initiation | Any BF Duration | Exclusive BF Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flower et al., 2008 North Carolina and Pennsylvania | Longitudinal cohort (788 WIC; 504 non-WIC) | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | |

| Jiang et al., 2010 U.S. nationwide | Secondary analysis of longitudinal data (1,373 WIC; 1,812 non-WIC) | ↓↓ (adjusted mean BF duration) ↔ (propensity matching) | ||

| Bunik et al., 2009 U.S. nationwide | Cross-sectional (2,492 WIC; 865 non-WIC) | ↔ | ↔ | |

| Hendricks et al., 2006 U.S. nationwide | Cross-sectional (626 WIC; 1,889 non-WIC) | ↔ | ↓↓ | |

| Jacknowitz et al., 2007 U.S. nationwide | Cross-sectional (4,221 WIC; 1,055 non-WIC) | ↓↓ | ||

| Jensen, 2012 U.S. nationwide | Cross-sectional (6,997 WIC; 1,188 non-WIC) | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | |

| Li et al., 2005 U.S. nationwide | Cross-sectional (1,705 WIC; 165 non-WIC) | ↓ | ||

| Ma et al., 2014 South Carolina | Cross-sectional (1,024 WIC; 214 non-WIC) | ↓↓ | ||

| Mao et al., 2012 Washington, DC | Cross-sectional (62 WIC; 189 non-WIC) | ↓ | ||

| Marshall et al., 2013 Mississippi | Cross-sectional (2,317 WIC; 1,177 non-WIC) | ↓↓ | ||

| Author, Year Location | Study Design (N) | BF Initiation | Any BF Duration | Exclusive BF Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ryan and Zhou, 2006 U.S. nationwide | Cross-sectional (213,613 WIC; 261,613 non-WIC) | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | |

| Shim et al., 2012 U.S. nationwide | Cross-sectional (3,830 WIC; 3,685 non-WIC) | ↓↓ | ||

| Sparks, 2011 U.S. nationwide | Cross-sectional (NR) | ↓↓ | ||

| Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010 U.S. nationwide | Cross-sectional (3,100 WIC; 1,350 non-WIC) | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↔ |

NOTES: BF = breastfeeding; NR = not reported; ↓ = WIC was significantly associated with lower BF initiation, shorter duration (continuous or categorical outcomes), or less exclusivity in unadjusted/crude analysis; ↓↓ = WIC was significantly associated with lower BF initiation, shorter duration (continuous or categorical outcomes), or less exclusivity in adjusted analysis; ↔ = no significant association; data excluded in summary if no significance tests were performed.

(Gundersen, 2005; Jiang et al., 2010). Chapter 3 includes a detailed discussion of the challenge posed by selective enrollment (“selection bias”) when analyzing WIC-specific data.

As mentioned in Chapter 2, studies of breastfeeding in the WIC population have shown that the prevalence varies among cultural groups, with the greatest differences appearing at the point of initiation. Although African Americans face similar barriers to breastfeeding that other women in the United States face, evidence suggests that they face these barriers to a greater extent (Spencer and Grassley, 2013). Sparks (2011) found that African American women were significantly less likely to initiate breastfeeding compared with women from other racial/ethnic groups, but this was no longer true when the model was adjusted for covariates. Several studies have indicated that African American women receive less encouragement to breastfeed from physicians and WIC counselors (Beal et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2015; Spencer et al., 2015). Evidence suggests that African American women experience unique historical, cultural, and structural barriers to initiating and sustaining breastfeeding. Several studies have noted that as compared to white women, African American women are less likely

to receive breastfeeding information and support from their health care providers (Spencer and Grassley, 2013) and WIC providers specifically (Beal et al., 2003). Additionally, historical images of African American women serving as wet nurses for white children during slavery (Gross et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2015) as well as existing perceptions of African American women as “strong” or “hypersexual” may also impede the support they received for breastfeeding both within and outside their African American community (Gross et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2015; Spencer et al., 2015). These and other barriers suggest a need for implementing multilevel approaches to promote and alleviate breastfeeding disparities among WIC and WIC-eligible women.

In addition to barriers to breastfeeding, researchers have identified multiple factors that facilitate breastfeeding initiation among both WIC participants and low-income women more generally. These include support from health care providers, breastfeeding promotion and assistance at the hospital, use of breastfeeding peer counselors, inclusion of lactation services in existing community-based programs, and supportive breastfeeding policies at the state and local levels (Ma and Magnus, 2012; CDC, 2014a; Lilleston et. al., 2015). However, the effectiveness of these approaches may vary among different racial and ethnic groups (Smith-Gagen et al., 2014).

Barriers to Breastfeeding

In its literature search, the committee identified many barriers to breastfeeding among WIC women (see Table 7-4) and in low-income populations generally. This section highlights barriers that the committee considers to be relevant to WIC and WIC-eligible populations.

Employment and Breastfeeding

Many women who choose to breastfeed do not continue into late infancy, which may result in part from the need to return to work. Several factors related to returning to work have been identified as barriers to breastfeeding, including anticipated lack of acceptance by coworkers (Rojjanasrirat and Sousa, 2010; Hedberg, 2013). Onsite lactation is another challenge. A goal of Healthy People 2020 is to ensure that 38 percent of employers provide an onsite lactation room (HHS, 2015), starting from a 2009 baseline of 25 percent. To help reach this goal, the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) required employers to provide a time and location to express human milk for 1 year after the child’s birth (DOL, 2011). However, while this amendment may have reduced barriers to breastfeeding for

some working mothers, its effect on the promotion of breastfeeding among WIC mothers is unclear.

Biomedical Barriers: Perceived Insufficient Milk (PIM) and Maternal Obesity

Perceived insufficient milk (PIM) is one of the most common reasons WIC mothers give for initiating formula supplementation and for discontinuing breastfeeding prematurely (USDA/FNS, 2012). PIM is likely to be the result of a combination of metabolic, physiological, and psychosocial factors and has been associated with both delayed onset of lactation and maternal obesity (Segura-Millán et al., 1994; Chapman and Pérez-Escamilla, 2000; Bever Babendure et al., 2015). As discussed in Chapter 6, maternal obesity has consistently been identified as a risk factor for poor breastfeeding outcomes among WIC women (Hauff et al., 2014; Turcksin et al., 2014), with breastfeeding interventions among obese mothers showing limited success (Chapman et al., 2013).

Lack of Access to Breast Pumps

Lack of access to breast pumps has been identified as a barrier to breastfeeding success among WIC mothers (Haughton et al., 2010; Hedberg, 2013). The Affordable Care Act’s requirement that most insurance companies cover the cost of breast pumps may be helping to remove this barrier (HHS, 2014).

Incentives to Breastfeeding

Important incentives identified in the literature included appropriately delivered professional advice (Heinig et al., 2009); support groups and group classes (Mickens et al., 2009; Tender et al., 2009; Varela et al., 2011); and clear and effective education from WIC (Murimi et al., 2010) including individual and peer counseling (Varela et al., 2011). Education in the hospital was also reported as an incentive to breastfeed (Ma and Magnus, 2012). On an individual level, existing perceptions (cultural or otherwise) of breastfeeding as beneficial was associated with an increased likelihood of breastfeeding (Heining et al., 2006; Vaaler et al., 2010; Wojcicki et al., 2010).

The provision of formula through WIC appears to be a major incentive for women to enroll in the program, but it competes as an incentive with the enhanced food package offered to breastfeeding mothers (see Chapter 2 for a review of relevant behavioral economics principles). Unfortunately, women enrolled in WIC or who are considering enrollment in the program

perceive the formula feeding package to be of higher economic value than the enhanced breastfeeding package (Haughton, 2010; Jensen and Labbok, 2011). For many women, the program delivers conflicting messages by supporting breastfeeding while at the same time distributing infant formula at no cost to participants (Holmes, 2009).

Association of the 2009 Food Package Revisions with Breastfeeding in the WIC Population

A key goal of the 2009 changes to the WIC food packages was to help improve breastfeeding behaviors. In its literature search, the committee identified six observational studies that have examined whether this goal was achieved. Collectively, the studies suggest that the enhanced food packages, together with improved support for breastfeeding in anticipation of the new packages, may have had a small effect on improving breastfeeding outcomes, although evidence is not conclusive. The six studies, all of which used a repeated cross-sectional design, are summarized here.

Based on a time-series analysis using data from three sources (2004–2010 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System [PRAMS] data covering 19 states, 2004–2010 National Immunization Survey [NIS] data from 50 states plus Washington, DC, and 2007–2010 Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System [PedNSS] data), Joyce and Reeder (2015) found that, between 2004 and 2010, breastfeeding outcomes improved among both WIC and low-income non-WIC participants. The trends in improvements in “any breastfeeding” and “breastfeeding for at least 4 weeks” were similar in both groups, and the increased prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding for at least 3 months was more pronounced among low-income non-WIC participants. The 2007–2010 PedNSS data showed a steady increase in ever-breastfeeding prevalence, but no acceleration in improvement around the time of the implementation of the food packages was detected.

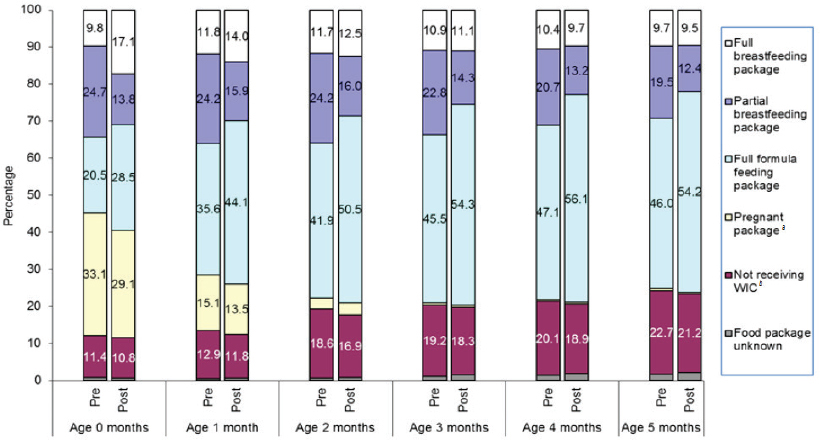

In an analysis of WIC administrative records in a large 10-state sample, Abt Associates found that participants’ choice of the partially breastfeeding package decreased from 24.7 percent before implementation of the revised packages to 13.8 percent afterward (see Figure 7-3) (USDA/FNS, 2011). While this decrease corresponded to an increase in the selection of the full breastfeeding package, an increase in the formula package and total amount of formula was also seen. Breastfeeding initiation did not appear to be affected by the revised food packages. An important limitation of this study is the short periods for the pre- and for post-implementation observations.

The committee also considered four regional studies. In a study conducted in New York State, Chiasson et al. (2013) reported an increase in the prevalence of breastfeeding initiation from 72.2 percent in 2008 to 77.5 percent in 2011. Similarly, two studies reported improved breastfeeding

NOTES: Data were sourced from the administrative records from 17 local state agencies. Data represent all dyads with infants aged 0 to 5 months, n = 129,606 (pre) and n = 528,597 (post) in analysis months 1–2 (pre) and analysis months 5–12 (post). Interpretation Guide: Among dyads whose infants were in their birth month, 9.8 percent (pre) and 17.1 percent (post) received the full breastfeeding package as the mother’s WIC food package.

a Mothers with infants certified for WIC.

b Mothers who have not recertified postpartum, but who have infants who have been certified.

SOURCE: USDA/FNS, 2011.

outcomes among WIC participants living in Los Angeles (Whaley et al., 2012; Langellier et al., 2014), with both ever-breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding at 3 and 6 months increasing between 2005 to 2008 and 2011 (Langellier et al., 2014). Finally, in a small pre-post cross-sectional study conducted in central Texas, Thornton et al. (2014) found small increases in both the prevalence of breastfeeding initiation and duration among WIC infants. Schultz et al. (2015) included the work of several of these research groups (Whaley et al., 2012; Wilde et al., 2012; Langellier et al., 2014) in their recent systematic review and also concluded the results of these studies were mixed.

Importantly, five of the aforementioned studies were based on pre/post or time-series designs without low-income, non-WIC participants as a comparison group. The only study that included such a comparison group, Joyce and Reeder (2015), concluded that, because improvements in

breastfeeding outcomes among WIC participants were similar to those of non-participants, the changes they observed in the WIC population were unlikely to be explained by the 2009 food package changes.

BREASTFEEDING INITIATION, DURATION, AND EXCLUSIVITY: INFLUENCE OF WIC PARTICIPATION

The committee’s literature search led to the identification of many studies with data describing the associations between WIC participation on breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity (see Table 7-4). Overall, the findings suggest WIC participation may be associated with a lower prevalence of breastfeeding. A summary of the literature follows.

Initiation

The committee identified nine studies on the association between WIC participation and breastfeeding initiation (Hendricks et al., 2006; Ryan and Zhou, 2006; Flower et al., 2008; Bunik et al., 2009; Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010; Jensen, 2012; Mao et al., 2012; Marshall et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2014). All but two (Hendricks et al., 2006; Bunik et al., 2009) reported that WIC participation was associated with significantly lower odds of breastfeeding initiation.

Duration

Several studies have reported associations between WIC participation and either lower odds of breastfeeding or higher risk for discontinuation of breastfeeding at 4, 6, or 12 months (Li et al., 2005; Hendricks et al., 2006; Ryan and Zhou, 2006; Flower et al., 2008; Bunik et al., 2009; Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010; Sparks, 2011; Shim et al., 2012). Additionally, in a cross-sectional study using data from the NIS, Jensen (2012) found that mean breastfeeding duration was 1.91 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.43, 2.40) months shorter in WIC participants than in WIC-eligible nonparticipants. In another study in which the mean duration of breastfeeding among WIC participants and nonparticipants was compared, Jiang et al. (2010) reported different results between two statistical analyses. Their multiple regression analysis showed that the adjusted mean breastfeeding duration was significantly longer in non-WIC participants than in WIC participants (3.88 versus 3.35 months). In their propensity matching analysis, they did not find a significant difference in the mean breastfeeding duration between WIC participants and nonparticipants. Inasmuch as propensity matching methods can balance baseline characteristics of the two-matched groups to reduce the self-selection bias, the difference between results obtained

by using these two approaches indicates that baseline demographic differences, rather than WIC participation, are more likely to explain the differences in the breastfeeding duration.

Exclusivity

Based on an analysis of data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), Ziol-Guest and Hernandez (2010) found no significant association between entry into WIC (at any trimester of pregnancy) and exclusive breastfeeding. In contrast, also based on an analysis of ECLS-B data, Jacknowitz et al. (2007) reported that WIC participants had 5.9 percent (95% CI −9.82%, −1.98%) and 1.9 percent (95% CI −3.82%, 0.06%) lower prevalences of exclusive breastfeeding for more than 4 and 6 months, respectively, compared with WIC-eligible nonparticipants. Li et al. (2005) also reported that exclusive breastfeeding was significantly less likely for individuals participating in WIC at 7 days and at 1, 3, and 6 months postpartum.

Associations Between the Timing of WIC Exposure and the Initiation, Duration, and Exclusivity of Breastfeeding

In its examination of the literature to determine whether the timing of a woman’s participation in WIC was associated with breastfeeding behavior, the committee identified seven analyses of either national longitudinal data (PRAMS and the ECLS-B) or regional survey data (Chicago, Kansas, Los Angeles, Louisiana, Massachusetts) (Joyce et al., 2008; Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010; Tenfelde et al., 2011; Langellier et al., 2012; Ma and Magnus, 2012; Jacobson et al., 2014; Metallinos-Katsaras et al., 2015). Details of most of these studies are provided in Appendix S, Table S-1. Some studies reported significant associations were found between earlier entry to WIC and breastfeeding initiation, any breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding, or breastfeeding duration, with some evidence of geographical variation (urban versus rural) (Joyce et al., 2008; Tenfelde et al., 2011; Jacobson et al., 2014; Metallinos-Katsaras et al., 2015). In contrast, other studies have shown negative or no associations between early WIC participation and breastfeeding initiation, breastfeeding at 4 months, exclusive breastfeeding, and breastfeeding duration (Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010; Langellier et al., 2012; Ma and Magnus, 2012). Findings from Ma and Magnus (2012) should be interpreted with caution as the analyses were not adjusted for confounders. Overall, these findings suggest that earlier entry into the WIC program is associated with an increased probability of any breastfeeding. The evidence is inconclusive regarding an association between timing of WIC entry and exclusivity or duration of breastfeeding.

Factors Other Than WIC Participation That Are Associated with Initiation, Duration, and Exclusivity of Breastfeeding

Aside from WIC participation and time of entry into the WIC program, the committee’s literature search identified a wide array of additional interrelated factors that may affect breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity among WIC women. Again, see Appendix S, Table S-1 for details. Highlights are summarized here. Many of the studies are qualitative, and few focus on the same factor.

Initiation

Initiation of breastfeeding among WIC-participating mothers has been positively associated with the following:

- Breastfeeding in the hospital after delivery (Ma and Magnus, 2012)

- Contact with a peer counselor (Gross et al., 2009)

- Foreign-born mothers (Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010)

- The mother being married (Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010; Darfour-Oduro and Kim, 2014)

- The mother being non-Hispanic white (Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010; Ma and Magnus, 2012) or Hispanic (Jacobson et al., 2014)

- Living in the Western United States (Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010)

- Mother’s income being above the poverty level (Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010)

- Participation in WIC for 3 months or longer (Yun et al., 2010)

- Older maternal age (age 45 or more) (Gross et al., 2009)

- Maternal overweight (Gross et al., 2009)

Breastfeeding initiation has been negatively associated with the receipt of food stamps, younger maternal age, and mothers being at or below the poverty level (Gross et al., 2009).

Duration

The duration of breastfeeding appears to be greater when mothers begin to breastfeed in the hospital (Langellier et al., 2012), when the mother is foreign-born (Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010; Langellier et al., 2012), and when child care is provided by a relative (Shim et al., 2012).

Exclusivity

Exclusive breastfeeding in WIC women has been positively associated with breastfeeding in the hospital after delivery (Langellier et al., 2012), higher income (Wojicki et al., 2010), prenatal intention to breastfeed (Tenfelde et al., 2011), higher maternal age and income (Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010), being non-Hispanic white (Langellier et al., 2012), and living in the Western United States (Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010). Exclusivity breastfeeding in WIC women has been negatively associated with the need to return to work (Langellier et al., 2012), receiving formula at the hospital (Langellier et al., 2012), pre-pregnancy overweight or obesity (Tenfelde et al., 2011), and being African American (Ziol-Guest and Hernandez, 2010).

Associations Between Breastfeeding Promotion Strategies and Initiation, Duration, and Exclusivity of Breastfeeding Among WIC Participants, and Among WIC-Eligible or Low-Income Populations

The committee identified 17 intervention studies evaluating associations between breastfeeding promotion and support strategies on the initiation, duration, and exclusivity of breastfeeding among WIC participants, and among WIC-eligible or low-income populations (Anderson et al., 2005, 2007; Bonuck et al., 2005; Hayes et al., 2008; Meehan et al., 2008; Hopkinson and Gallagher, 2009; Petrova et al., 2009; Sandy et al., 2009; Bunik et al., 2010; Olson et al., 2010; Pugh et al., 2010; Kandiah, 2011; Chapman et al., 2013; Haider et al., 2014; Hildebrand et al., 2014; Howell et al., 2014; Reeder et al., 2014). Interventions included professional support, lay support, breast pumps, telephone breastfeeding support, and education. Multimodal intervention deliveries were employed including individual face-to-face, group, and telephone support. Comparison groups and characteristics of study participants were heterogeneous across studies. The findings from this body of literature are presented in Appendix S.

Initiation

Overall, multimodal professional and lay breastfeeding support increased the proportions of women who initiated breastfeeding by 19 to 50 percent compared to standard of care without breastfeeding support (Olson et al., 2010; Haider et al., 2014; Hildebrand et al., 2014). However, in one study the same proportion of women (84 percent) initiated breastfeeding in low-income mothers who received behavioral educational intervention and those who received an enhanced usual care (Howell et al., 2014).

Duration

In six intervention studies, professional and/or lay breastfeeding support was associated with the increased occurrence of any breastfeeding up to 6 months (Bonuck et al., 2005; Olson et al., 2010; Pugh et al., 2010; Chapman et al., 2013; Haider et al., 2014; Reeder et al., 2014), but the effects were not maintained at 9 and 12 months postpartum (Olson et al., 2010; Haider et al., 2014). However, one study did not find significant effects of breastfeeding promotion or support on prevalence of any breastfeeding compared with standard care (Bunik et al., 2010). One other study that compared electric breast pumps with manual breast pumps also did not find significant difference in the prevalence of breastfeeding at 6 months (Hayes et al., 2008; see Appendix S, Figure S-2).

Furthermore, results from four studies showed that breastfeeding support (breast pump, education and infant hunger cue, and lay support) can increase the duration of any breastfeeding by an average of 2 to 17 weeks compared with control interventions (Meehan et al., 2008; Olson et al., 2010; Kandiah, 2011; Haider et al., 2014) (see Appendix S, Figure S-3).

Exclusivity

Of the seven studies that reported breastfeeding exclusivity outcomes, four showed that breastfeeding promotion or support significantly increased the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding at 1 week to 3 months (Anderson et al., 2005, 2007; Hopkinson and Gallagher, 2009; Sandy et al., 2009). However, the other three studies found no significant difference in the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding (ranging from 1 week to at least 6 months) between breastfeeding support (telephone peer counseling or education) and controls (Petrova et al., 2009; Howell et al., 2014; Reeder et al., 2014).

REFERENCES

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). 2014. Pediatric nutrition, edited by R. E. Kleinman and F. R. Greer, 7th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Aguilar Cordero, M. J., N. Madrid Banos, L. Baena Garcia, N. Mur Villar, R. Guisado Barrilao, and A. M. Sanchez Lopez. 2015. Breastfeeding as a method to prevent cardiovascular diseases in the mother and the child. Nutricion Hospitalaria 31(5):1936-1946.

Amitay, E. L., and L. Keinan-Boker. 2015. Breastfeeding and childhood leukemia incidence: A meta-analysis and systematic review. JAMA Pediatrics 169(6):e151025.

Anderson, A. K., G. Damio, S. Young, D. J. Chapman, and R. Pérez-Escamilla. 2005. A randomized trial assessing the efficacy of peer counseling on exclusive breastfeeding in a predominantly Latina low-income community. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 159(9):836-841.

Anderson, A. K., G. Damio, D. J. Chapman, and R. Pérez-Escamilla. 2007. Differential response to an exclusive breastfeeding peer counseling intervention: The role of ethnicity. Journal of Human Lactation 23(1):16-23.

Anderson, J., D. Hayes, and L. Chock. 2014. Characteristics of overweight and obesity at age two and the association with breastfeeding in Hawaii Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) participants. Maternal and Child Health Journal 18(10):2323-2331.

Barroso, C. S., A. Roncancio, M. B. Hinojosa, and E. Reifsnider. 2012. The association between early childhood overweight and maternal factors. Childhood Obesity 8(5):449-454.

Beal, A. C., K. Kuhlthau, and J. M. Perrin. 2003. Breastfeeding advice given to African American and white women by physicians and WIC counselors. Public Health Reports 118(4):368-376.

Bever Babendure, J., E. Reifsnider, E. Mendias, M. W. Moramarco, and Y. R. Davila. 2015. Reduced breastfeeding rates among obese mothers: A review of contributing factors, clinical considerations and future directions. International Breastfeeding Journal 10:21.

Bonuck, K. A., M. Trombley, K. Freeman, and D. McKee. 2005. Randomized, controlled trial of a prenatal and postnatal lactation consultant intervention on duration and intensity of breastfeeding up to 12 months. Pediatrics 116(6):1413-1426.

Bunik, M., N. F. Krebs, B. Beaty, M. McClatchey, and D. L. Olds. 2009. Breastfeeding and WIC enrollment in the nurse family partnership program. Breastfeeding Medicine 4(3):145-149.

Bunik, M., P. Shobe, M. E. O’Connor, B. Beaty, S. Langendoerfer, L. Crane, and A. Kempe. 2010. Are 2 weeks of daily breastfeeding support insufficient to overcome the influences of formula? Academic Pediatrics 10(1):21-28.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2010. Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration, by state—National Immunization Survey, United States, 2004–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 59(11):327-334.

CDC. 2014a. Breastfeeding report card. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/2014breastfeedingreportcard.pdf (accessed June 2, 2015).

CDC. 2014b. Racial disparities in access to maternity care practices that support breastfeeding—United States, 2011. MMWR: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 63(33):725-728.

CDC. 2015. National Immunization Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nis.htm (accessed June 2, 2015).

Chapman, D. J., and R. Pérez-Escamilla. 2000. Maternal perception of the onset of lactation is a valid, public health indicator of lactogenesis stage II. Journal of Nutrition 130(12):2972-2980.

Chapman, D. J., K. Morel, A. Bermudez-Millan, S. Young, G. Damio, and R. Pérez-Escamilla. 2013. Breastfeeding education and support trial for overweight and obese women: A randomized trial. Pediatrics 131(1):e162-e170.

Chiasson, M. A., S. E. Findley, J. P. Sekhobo, R. Scheinmann, L. S. Edmunds, A. S. Faly, and N. J. McLeod. 2013. Changing WIC changes what children eat. Obesity (Silver Spring) 21(7):1423-1429.

Chowdhury, R., B. Sinha, M. J. Sankar, S. Taneja, N. Bhandari, N. Rollins, R. Bahl, and J. Martines. 2015. Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica. doi:10.1111/apa.13102.

Colen, G. G., and D. M. Ramey. 2014. Is breast truly best? Estimating the effects of breastfeeding on long-term child health and wellbeing in the United States using sibling comparisons. Social Science and Medicine 109:55-65.

Cope, M. B., and D. B. Allison. 2008. Critical review of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2007 report on evidence for the long-term effects of breastfeeding: Systematic review and meta-analysis’ with respect to obesity. Obesity Reviews 9(6):594-605.

Darfour-Oduro, S. A., and J. Kim. 2014. WIC mothers’ social environment and postpartum health on breastfeeding initiation and duration. Breastfeeding Medicine 9(10):524-529.

Davis, J. N., S. E. Whaley, and M. I. Goran. 2012. Effects of breastfeeding and low sugar-sweetened beverage intake on obesity prevalence in Hispanic toddlers. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 95(1):3-8.

Davis, J. N., M. Koleilat, G. E. Shearrer, and S. E. Whaley. 2014. Association of infant feeding and dietary intake on obesity prevalence in low-income toddlers. Obesity (Silver Spring) 22(4):1103-1111.

Dennison, B. A., L. S. Edmunds, H. H. Stratton, and R. M. Pruzek. 2006. Rapid infant weight gain predicts childhood overweight. Obesity (Silver Spring) 14(3):491-499.

DOL (U.S. Department of Labor). 2011. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, as amended. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor. http://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/statutes/FairLaborStandAct.pdf (accessed June 1, 2015).

Edmunds, L. S., J. P. Sekhobo, B. A. Dennison, M. A. Chiasson, H. H. Stratton, and K. K. Davison. 2014. Association of prenatal participation in a public health nutrition program with healthy infant weight gain. American Journal of Public Health 104(Suppl 1):S35-S42.

Flower, K. B., M. Willoughby, R. J. Cadigan, E. M. Perrin, and G. Randolph. 2008. Understanding breastfeeding initiation and continuation in rural communities: A combined qualitative/quantitative approach. Maternal and Child Health Journal 12(3):402-414.

Gertosio, C., C. Meazza, S. Pagani, and M. Bozzola. 2015. Breast feeding: Gamut of benefits. Minerva Pediatrica. Published electronically May 29, 2015.

Gross, S. M., A. K. Resnik, C. Cross-Barnet, J. P. Nanda, M. Augustyn, and D. M. Paige. 2009. The differential impact of WIC peer counseling programs on breastfeeding initiation across the state of Maryland. Journal of Human Lactation 25(4):435-443.

Gross, T. T., R. Powell, A. K. Anderson, J. Hall, M. Davis, and K. Hilyard. 2015. WIC peer counselors’ perceptions of breastfeeding in African American women with lower incomes. Journal of Human Lactation 31(1):99-110.

Grummer-Strawn, L. 2011. Teleconf-handout-socio-ecologic-model. CDC-USBC Bi-Monthly Teleconferences. http://www.usbreastfeeding.org/p/cm/ld/fid=250&tid=551&sid=75 (accessed October 23, 2015).

Gundersen, C. 2005. A dynamic analysis of the well-being of WIC recipients and eligible non-recipients. Children and Youth Services Review 27(1):99-114.

Gunderson, E. P., C. P. J. Quesenberry, X. Ning, D. R. J. Jacobs, M. Gross, D. C. J. Goff, M. J. Pletcher, and C. E. Lewis. 2015. Lactation duration and midlife atherosclerosis. Obstetrics and Gynecology 126(2):381-390.

Haider, S. J., L. V. Chang, T. A. Bolton, J. G. Gold, and B. H. Olson. 2014. An evaluation of the effects of a breastfeeding support program on health outcomes. Health Services Research 49(6):2017-2034.

Hauff, L. E., S. A. Leonard, and K. M. Rasmussen. 2014. Associations of maternal obesity and psychosocial factors with breastfeeding intention, initiation, and duration. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 99(3):524-534.

Haughton, J., D. Gregorio, and R. Pérez-Escamilla. 2010. Factors associated with breastfeeding duration among Connecticut Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) participants. Journal of Human Lactation 26(3):266-273.

Hayes, D. K., C. B. Prince, V. Espinueva, L. J. Fuddy, R. Li, and L. M. Grummer-Strawn. 2008. Comparison of manual and electric breast pumps among WIC women returning to work or school in Hawaii. Breastfeeding Medicine 3(1):3-10.

Hedberg, I. C. 2013. Barriers to breastfeeding in the WIC population. MCN: American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing 38(4):244-249.

Heinig, M. J., J. R. Follett, K. D. Ishii, K. Kavanagh-Prochaska, R. Cohen, and J. Panchula. 2006. Barriers to compliance with infant-feeding recommendations among low-income women. Journal of Human Lactation 22(1):27-38.

Heinig, M. J., K. D. Ishii, J. L. Banuelos, E. Campbell, C. O’Loughlin, and L. E. Vera Becerra. 2009. Sources and acceptance of infant-feeding advice among low-income women. Journal of Human Lactation 25(2):163-172.

Hendricks, K., R. Briefel, T. Novak, and P. Ziegler. 2006. Maternal and child characteristics associated with infant and toddler feeding practices. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 106(1 Suppl 1):S135-S148.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2011. The surgeon general’s call to action to support breastfeeding. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/calls/breastfeeding/calltoactiontosupportbreastfeeding.pdf (accessed June 2, 2015).

HHS. 2014. Breast pumps and insurance coverage: What you need to know. http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/prevention/breast-pumps (accessed September 3, 2015).

HHS. 2015. Healthy People 2020: Maternal, infant, and child health objectives. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives (accessed June 1, 2015).

HHS/CDC. 2015. Nutrition, physical activity and obesity data, trends and maps website. http://nccd.cdc.gov/NPAO_DTM/Default.aspx (accessed October 7, 2015).

Hildebrand, D. A., P. McCarthy, D. Tipton, C. Merriman, M. Schrank, and M. Newport. 2014. Innovative use of influential prenatal counseling may improve breastfeeding initiation rates among WIC participants. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 46(6):458-466.

Holmes, A. V., N. P. Chin, J. Kaczorowski, and C. R. Howard. 2009. A barrier to exclusive breastfeeding for WIC enrollees: Limited use of exclusive breastfeeding food package for mothers. Breastfeeding Medicine 4(1):25-30.

Hopkinson, J., and M. Konefal Gallagher. 2009. Assignment to a hospital-based breastfeeding clinic and exclusive breastfeeding among immigrant Hispanic mothers: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Human Lactation 25(3):287-296.

Horta, B. L., C. L. de Mola, and C. G. Victora. 2015a. Breastfeeding and intelligence: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica. Published electronically July 7, 2015. doi:10.1111/apa.13139.

Horta, B. L., C. L. de Mola, and C. G. Victora. 2015b. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure, and type 2 diabetes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica. Published electronically July 20, 2015. doi:10.1111/apa.13133.

Howell, E. A., S. Bodnar-Deren, A. Balbierz, M. Parides, and N. Bickell. 2014. An intervention to extend breastfeeding among black and Latina mothers after delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 210(3):239.e231-e235.

Hurst, C. 2007. Constraints on breastfeeding choices for low-income mothers. Ph.D. thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. Updating the USDA national breastfeeding campaign: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Ip, S., M. Chung, G. Raman, P. Chew, N. Magula, D. DeVine, T. Trikalinos, and J. Lau. 2007. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (153):1-186.

Jacknowitz, A., D. Novillo, and L. Tiehen. 2007. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children and infant feeding practices. Pediatrics 119(2):281-289.

Jacobson, L. T., P. Twumasi-Ankrah, M. L. Redmond, E. Ablah, R. B. Hines, J. Johnston, and T. C. Collins. 2014. Characteristics associated with breastfeeding behaviors among urban versus rural women enrolled in the Kansas WIC program. Maternal and Child Health Journal 19(4):828-839.

Jenkins, J. M., and E. M. Foster. 2015. The effects of breastfeeding exclusivity on early childhood outcomes. American Journal of Public Health 104:S128-S135.

Jensen, E. 2012. Participation in the supplemental nutrition program for women, infants and children (WIC) and breastfeeding: National, regional, and state level analyses. Maternal and Child Health Journal 16(3):624-631.

Jensen, E., and M. Labbok. 2011. Unintended consequences of the WIC formula rebate program on infant feeding outcomes: Will the new food packages be enough? Breastfeeding Medicine 6(3):145-149.

Jiang, M., E. M. Foster, and C. M. Gibson-Davis. 2010. The effect of WIC on breastfeeding: A new look at an established relationship. Children and Youth Services Review 32(2):264-273.

Johnson, A., R. Kirk, K. L. Rosenblum, and M. Muzik. 2015. Enhancing breastfeeding rates among African American women: A systematic review of current psychosocial interventions. Breastfeeding Medicine 10:45-62.

Johnston-Robledo, I., and V. Fred. 2008. Self-objectification and lower income pregnant women’s breastfeeding attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 38(1):1-21.

Joyce, T., and J. Reeder. 2015. Changes in breastfeeding among WIC participants following implementation of the new food package. Maternal and Child Health Journal 19(4):868-876.

Joyce, T., A. Racine, and C. Yunzal-Butler. 2008. Reassessing the WIC effect: Evidence from the pregnancy nutrition surveillance system. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 27(2):277-303.

Kandiah, J. 2011. Teaching new mothers about infant feeding cues may increase breastfeeding duration. Food and Nutrition Sciences 02(04):259-264.

Krause, K. M., C. A. Lovelady, B. L. Peterson, N. Chowdhury, and T. Ostbye. 2010. Effect of breast-feeding on weight retention at 3 and 6 months postpartum: Data from the North Carolina WIC programme. Public Health Nutrition 13(12):2019-2026.

Langellier, B. A., M. Pia Chaparro, and S. E. Whaley. 2012. Social and institutional factors that affect breastfeeding duration among WIC participants in Los Angeles County, California. Maternal and Child Health Journal 16(9):1887-1895.

Langellier, B. A., M. P. Chaparro, M. C. Wang, M. Koleilat, and S. E. Whaley. 2014. The new food package and breastfeeding outcomes among Women, Infants, and Children participants in Los Angeles county. American Journal of Public Health 104(Suppl 1):S112-S118.

Li, R., N. Darling, E. Maurice, L. Barker, and L. M. Grummer-Strawn. 2005. Breastfeeding rates in the United States by characteristics of the child, mother, or family: The 2002 National Immunization Survey. Pediatrics 115(1):e31-e37.

Lilleston, P., K. Nhim, and G. Rutledge. 2015. An evaluation of the CDC’s community-based breastfeeding supplemental cooperative agreement: Reach, strategies, barriers, facilitators, and lessons learned. Journal of Human Lactation. Published electronically August 12, 2015. doi:10.1177/0890334415597904.

Lindberg, S. M., A. K. Adams, and R. J. Prince. 2012. Early predictors of obesity and cardiovascular risk among American Indian children. Maternal and Child Health Journal 16(9):1879-1886.

Lodge, C. J., D. J. Tan, M. Lau, X. Dai, R. Tham, A. J. Lowe, G. Bowatte, K. J. Allen, and S. C. Dharmage. 2015. Breastfeeding and asthma and allergies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica. Published electronically July 20, 2015. doi:10.1111/apa.13132.

Ma, P., and J. H. Magnus. 2012. Exploring the concept of positive deviance related to breastfeeding initiation in black and white WIC enrolled first time mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal 16(8):1583-1593.

Ma, X., J. Liu, and M. Smith. 2014. WIC participation and breastfeeding in South Carolina: Updates from prams 2009–2010. Maternal and Child Health Journal 18(5):1271-1279.

Maalouf-Manasseh, Z., E. Metallinos-Katsaras, and K. G. Dewey. 2011. Obesity in preschool children is more prevalent and identified at a younger age when who growth charts are used compared with CDC charts. Journal of Nutrition 141(6):1154-1158.

Mao, C. Y., S. Narang, and J. Lopreiato. 2012. Breastfeeding practices in military families: A 12-month prospective population-based study in the national capital region. Military Medicine 177(2):229-234.

Marshall, C., L. Gavin, C. Bish, A. Winter, L. Williams, M. Wesley, and L. Zhang. 2013. WIC participation and breastfeeding among white and black mothers: Data from Mississippi. Maternal and Child Health Journal 17(10):1784-1792.

Meehan, K., G. G. Harrison, A. A. Afifi, N. Nickel, E. Jenks, and A. Ramirez. 2008. The association between an electric pump loan program and the timing of requests for formula by working mothers in WIC. Journal of Human Lactation 24(2):150-158.

Metallinos-Katsaras, E., L. Brown, and R. Colchamiro. 2015. Maternal WIC participation improves breastfeeding rates: A statewide analysis of WIC participants. Maternal and Child Health Journal 19(1):136-143.

Mickens, A. D., N. Modeste, S. Montgomery, and M. Taylor. 2009. Peer support and breastfeeding intentions among black WIC participants. Journal of Human Lactation 25(2):157-162.

Murimi, M., C. M. Dodge, J. Pope, and D. Erickson. 2010. Factors that influence breastfeeding decisions among Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children participants from central Louisiana. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 110(4):624-627.

Olson, B. H., S. J. Haider, L. Vangjel, T. A. Bolton, and J. G. Gold. 2010. A quasi-experimental evaluation of a breastfeeding support program for low-income women in Michigan. Maternal and Child Health Journal 14(1):86-93.

Østbye, T., K. M. Krause, G. K. Swamy, and C. A. Lovelady. 2010. Effect of breastfeeding on weight retention from one pregnancy to the next: Results from the North Carolina WIC program. Preventive Medicine 51(5):368-372.

Pérez-Escamilla, R., and D. J. Chapman. 2012. Breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support in the United States: A time to nudge, a time to measure. Journal of Human Lactation 28(2):118-121.

Pérez-Escamilla, R., L. Curry, D. Minhas, L. Taylor, and E. Bradley. 2012. Scaling up of breastfeeding promotion programs in low- and middle-income countries: The “breastfeeding gear” model. Advances in Nutrition 3(6):790-800.

Petrova, A., C. Ayers, S. Stechna, J. A. Gerling, and R. Mehta. 2009. Effectiveness of exclusive breastfeeding promotion in low-income mothers: A randomized controlled study. Breastfeeding Medicine 4(2):63-69.

Pugh, L. C., J. R. Serwint, K. D. Frick, J. P. Nanda, P. W. Sharps, D. L. Spatz, and R. A. Milligan. 2010. A randomized controlled community-based trial to improve breastfeeding rates among urban low-income mothers. Academic Pediatrics 10(1):14-20.

Reeder, J. A., T. Joyce, K. Sibley, D. Arnold, and O. Altindag. 2014. Telephone peer counseling of breastfeeding among WIC participants: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 134(3):e700-e709.

Reifsnider, E., and M. Ritsema. 2008. Ecological differences in weight, length, and weight for length of Mexican American children in the WIC program. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing 13(3):154-167.

Rojjanasrirat, W., and V. D. Sousa. 2010. Perceptions of breastfeeding and planned return to work or school among low-income pregnant women in the USA. Journal of Clinical Nursing 19(13-14):2014-2022.

Ryan, A. S. 2005. More about the Ross Mothers Survey. Pediatrics 115(5):1450-1451.

Ryan, A. S., and W. Zhou. 2006. Lower breastfeeding rates persist among the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children participants, 1978–2003. Pediatrics 117(4):1136-1146.

Ryan, A., Z. Wenjun, and A. Acosta. 2002. Breastfeeding continues to increase into the new millennium. Pediatrics 11(6):1103-1109.

Sandy, J. M., E. Anisfeld, and E. Ramirez. 2009. Effects of a prenatal intervention on breastfeeding initiation rates in a Latina immigrant sample. Journal of Human Lactation 25(4):404-411; quiz 458-459.

Schultz, D. J., C. Byker Shanks, and B. Houghtaling. 2015. The Impact of the 2009 Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children food package revisions on participants: A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 115(11):1832-1846.

Segura-Millan, S., K. G. Dewey, and R. Perez-Escamilla. 1994. Factors associated with perceived insufficient milk in a low-income urban population in Mexico. Journal of Nutrition 124(2):202-212.

Shearrer, G. E., S. E. Whaley, S. J. Miller, B. T. House, T. Held, and J. N. Davis. 2015. Association of gestational diabetes and breastfeeding on obesity prevalence in predominately Hispanic low-income youth. Pediatric Obesity 10(3):165-171.

Shim, J. E., J. Kim, and J. B. Heiniger. 2012. Breastfeeding duration in relation to child care arrangement and participation in the special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Journal of Human Lactation 28(1):28-35.

Smith-Gagen, J., R. Hollen, M. Walker, D. M. Cook, and W. Yang. 2014. Breastfeeding laws and breastfeeding practices by race and ethnicity. Women’s Health Issues 24(1):e11-e19.

Smithers, L. G., M. S. Kramer, J. W. Lynch. 2015. Effects of breastfeeding on obesity and intelligence: causal insights from different study designs. JAMA Pediatrics 169(8):707-708.

Sparks, P. J. 2011. Racial/ethnic differences in breastfeeding duration among WIC-eligible families. Women’s Health Issues 21(5):374-382.

Spencer, B. S., and J. S. Grassley. 2013. African American women and breastfeeding: An integrative literature review. Health Care for Women International 34(7):607-625.

Spencer, B., K. Wambach, and E. W. Domain. 2015. African American women’s breastfeeding experiences: Cultural, personal, and political voices. Qualitative Health Research 25(7):974-987.

Stolzer, J. M. 2010. Breastfeeding and WIC participants: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Poverty 14(4):423-442.

Tender, J. A. F., J. Janakiram, E. Arce, R. Mason, T. Jordan, J. Marsh, S. Kin, J. He, and R. Y. Moon. 2009. Reasons for in-hospital formula supplementation of breastfed infants from low-income families. Journal of Human Lactation 25(1):11-17.

Tenfelde, S., L. Finnegan, and P. D. Hill. 2011. Predictors of breastfeeding exclusivity in a WIC sample. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 40(2):179-189.

Tenfelde, S., R. Zielinski, and R. L. Heidarisafa. 2013. Why WIC women stop breastfeeding?: Analysis of maternal characteristics and time to cessation. Infant, Child, and Adolescent Nutrition 5(4):207-214.

Tham, R., G. Bowatte, S. C. Dharmage, D. J. Tan, M. Lau, X. Dai, K. J. Allen, and C. J. Lodge. 2015. Breastfeeding and the risk of dental caries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica. Published electronically July 24, 2015. doi:10.1111/apa.13118.

Thornton, H. E., S. H. Crixell, A. M. Reat, and J. A. Von Bank. 2014. Differences in energy and micronutrient intakes among central Texas WIC infants and toddlers after the package change. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 46(3 Suppl):S79-S86.

Turcksin, R., S. Bel, S. Galjaard, and R. Devlieger. 2014. Maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation, intensity and duration: A systematic review. Maternal & Child Nutrition 10(2):166-183.

USDA/ERS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Economic Research Service). 2010. Rising infant formula costs to the WIC program recent trends in rebates and wholesale prices. Washington, DC: USDA/ERS. http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/136568/err93_1_.pdf (accessed March 9, 2015).

USDA/FNS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Food and Nutrition Service). 2011. Evaluation of the birth month breastfeeding changes to the WIC food packages. Arlington, VA: USDA/FNS. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/BirthMonth.pdf (accessed March 9, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2012. National survey of WIC participants II: Volume 1: Participant characteristics (final report). Washington, DC: USDA/FNS. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/NSWP-II.pdf (accessed April 13, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2013. WIC participant and program characteristics 2012 final report. Alexandria, VA: USDA/FNS. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/WICPC2012.pdf (accessed December 20, 2014).

Vaaler, M. L., J. Stagg, S. E. Parks, T. Erickson, and B. C. Castrucci. 2010. Breast-feeding attitudes and behavior among WIC mothers in Texas. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 42(3 Suppl):S30-S38.

Varela Ruiz, M., H. Arroyo, R. R. Davila Torres, M. I. Matos Vera, and V. E. Reyes Ortiz. 2011. Qualitative study on WIC program strategies to promote breastfeeding practices in Puerto Rico: What do nutritionist/dieticians think? Maternal and Child Health Journal 15(4):520-526.

Whaley, S. E., M. Koleilat, M. Whaley, J. Gomez, K. Meehan, and K. Saluja. 2012. Impact of policy changes on infant feeding decisions among low-income women participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. American Journal of Public Health 102(12):2269-2273.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2009. Baby-friendly hospital initiative: Revised, updated and expanded for integrated care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/bfhi_trainingcourse/en (accessed September 3, 2015).

WHO. 2013. Long-term effects of breastfeeding: A systematic review. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Wojcicki, J. M., R. Gugig, C. Tran, S. Kathiravan, K. Holbrook, and M. B. Heyman. 2010. Early exclusive breastfeeding and maternal attitudes towards infant feeding in a population of new mothers in San Francisco, California. Breastfeeding Medicine 5(1):9-15.

Yun, S., Q. Liu, K. Mertzlufft, C. Kruse, M. White, P. Fuller, and B. P. Zhu. 2010. Evaluation of the Missouri WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) breast-feeding peer counselling programme. Public Health Nutrition 13(2):229-237.

Ziol-Guest, K. M., and D. C. Hernandez. 2010. First- and second-trimester WIC participation is associated with lower rates of breastfeeding and early introduction of cow’s milk during infancy. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 110(5):702-709.