1

Introduction and Background

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) was piloted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS) in 1972 and enacted into legislation in 1975 (USDA/ERS, 2009). The WIC program is designed to provide specific nutrients determined by nutritional research to be lacking in the diets of the WIC target population (7 CFR § 246). To qualify for participation, applicants must meet eligibility criteria for life stage, income, and nutritional risk.1 Participants can receive benefits through vouchers or, more recently in some states, an electronic benefit transfer (EBT) card. WIC is administered as a federal grant to the 50 states and the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, the American Virgin Islands, the Northern Mariana Islands, and 34 Indian Tribal Organizations (USDA/FNS, 2013a). The program is currently funded by appropriations set aside as part of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, which is scheduled for reauthorization in late 2015. In 2014, the WIC program served approximately 8.2 million women, infants, and children through 1,900 local agencies in 10,000 clinic sites (USDA/FNS, 2015a). Approximately 50 percent of infants and 40 percent of pregnant women in the U.S.

__________________

1 Specifically, participants must be the following: (1) either women who are pregnant and up to 6 months, or, if breastfeeding, 1 year postpartum; infants; or children up to 5 years of age; (2) at or below 185 percent of federal poverty guidelines or enrolled in Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or Medicaid; and (3) at nutritional risk (e.g., anemia, obesity, underweight, high-risk pregnancy).

benefit from WIC services (USDA/FNS, 2015b; Personal communication, J. Hirschman, USDA-FNS, October 15, 2014).

Although the mission of WIC remains the same, that is, to “safeguard the health of low-income women, infants, and children up to age 5 who are at nutritional risk” (USDA/FNS, 2012), the goals of the WIC program have evolved since its introduction. Today they include promoting and supporting successful long-term breastfeeding; providing WIC participants with a wider variety of foods, including fruits, vegetables, and whole grains; and providing WIC state agencies greater flexibility in prescribing food packages to accommodate cultural food preferences of WIC participants (USDA/FNS, 2014a). WIC supports the national health goals of Healthy People 2020, specifically those related to birth weight, childhood and adult weight, and breastfeeding prevalence (NWA, 2013; HHS, 2014).

In 2006, an Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee proposed the first significant revisions to the WIC food packages since inception of the program (IOM, 2006). Table C-1 in Appendix C shows major changes proposed in 2006 compared to corresponding federal regulations and available state options for implementation as outlined in the March 2014 final rule (USDA/FNS, 2014a). The revisions, which were initially implemented in 2009 (USDA/FNS, 2007b) and finalized in 2014 (USDA/FNS, 2014a), resulted in dramatic changes to the food packages (see Appendix D, Tables D1 and D2 for information on the current food packages). Most, but not all, of the 2006 IOM report recommendations were fully implemented. For example, recommendations to add a cash value voucher (CVV) for the purchase of fruits and vegetables and to reduce the quantities of milk, cheese, and eggs in the food packages were implemented fully. Other recommendations, however, underwent modification before implementation. As an example, the recommendation to allow only whole grain breakfast cereals was modified to require that at least one-half of all breakfast cereal on each state agency’s authorized food list have whole grain as the primary ingredient by weight, thereby providing participants with a choice to continue to purchase breakfast cereals that are not whole grain. Finally, some recommendations were not implemented at all. For example, the proposed addition of a higher-value CVV for breastfeeding mothers was not implemented, with the 2014 final rule specifying that breastfeeding women would receive the same value CVV as all other women participants (USDA/FNS, 2014a). Table 1-1 illustrates that while most changes were implemented by fall of 2009 in accordance with the interim rule (USDA/FNS, 2007a), changes have been implemented over a period of 6 years. The final change (i.e., allowing a yogurt substitution for milk) was still underway at the time of this writing.

A number of research activities have been undertaken to evaluate the impact of WIC generally and the food package changes specifically. As

TABLE 1-1 Timeline for Implementation of the Most Recent WIC Food Package Changes

| Deadline for Implementation | Action of State Agencies | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1992 | FP VII was created to encourage breastfeeding, added two new items: carrots and canned tuna, along with increased amounts of juice, cheese, beans/peas, and peanut butter for women who exclusively breastfeed their infants | WIC Program: Background, Trends, and Economic Issues (USDA/ERS, 2009) |

| October 1, 2009 | New WIC food packages effective February 4, 2008 (CVV for fruits and vegetables, added whole grains, reduced amount of juice, milk, cheese and eggs, allowed greater substitution of foods), must be implemented by August 5, 2009, according to the Interim Rule, later changed to October 1, 2009, to align with the federal fiscal year | WIC Interim Rule (December 6, 2007); WIC Program: Background, Trends, and Economic Issues (USDA/ERS, 2009) |

| June 2, 2014 | CVV must increase for children from $6 to $8 | WIC Final Rule (March 4, 2014) |

| October 1, 2014 | State agencies may issue authorized soy-based beverages or tofu to children who receive FP IV based on the determination of a competent professional authority | WIC Final Rule (March 4, 2014) |

| October 1, 2014 | States must require only low-fat (1%) or nonfat milks for children more than age 2 and women in FP IV–VII | WIC Policy Memorandum 2014-6 (USDA/FNS, 2014b) |

| January 15, 2015 | States are required to include white potatoes to be eligible for purchase with CVV 15 days after the date of enactment (December 31, 2014), all implementations including education and new product lists completed by July 1, 2015 | WIC Policy Memorandum 2015-3 (USDA/FNS, 2015c) |

| April 1, 2015 | Split tender CVV must be implemented | WIC Final Rule (March 4, 2014) |

| April 1, 2015 | States may authorize yogurt for children and women in FP III and VII | WIC Final Rule (March 4, 2014) |

| October 1, 2015 | CVV for women must increase from $10 to $11 | WIC Policy Memorandum 2015-4 (USDA/FNS, 2015d) |

NOTES: CVV = cash value voucher; FP = food package. See Appendix D for detail on composition of the WIC food packages.

shown in Appendix E, Table E-1, USDA-sponsored investigators have studied changes in the behavior of vendors, the availability of vegetables and fruits for purchase with the CVV, the availability of foods in new package sizes, and the pattern of household-level food purchases.

More recently, in response to a request from Congress, the USDA-FNS charged the IOM’s current Committee to Review the WIC Food Packages to conduct a two-phase evaluation of the WIC food packages and develop recommendations for revising the packages to be consistent with the 2015 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) and to consider the health and cultural needs of a diverse WIC population while remaining cost neutral, efficient for nationwide distribution, and nonburdensome to administration in national, state, and local agencies. The statement of task for this study is presented in Box 1-1.

This report is the second of three reports aimed at fulfilling the USDA-FNS request. The first report in the series, Review of WIC Food Packages: An Evaluation of White Potatoes in the Cash Value Voucher: Letter Report

(IOM, 2015), assessed the impact on food and nutrient intakes of the WIC population of the 2009 regulation to allow the purchase of vegetables and fruits, excluding white potatoes, with a CVV and recommended that white potatoes be allowed as a WIC-eligible vegetable (IOM, 2015). For this second (interim) report, the committee was tasked with a more comprehensive review of evidence to support the development of recommendations that will appear in the final (phase II) report. This review of evidence supported the development of the proposed criteria and framework to be used for possible food package revisions in phase II.

The evidence and analyses summarized in this report are limited by the statement of task. Although the committee’s review of evidence took into account that food selection and preparation affects the nutrient composition of the diet, some aspects of food preparation were beyond the scope of its task. Specifically, the addition of fat from butter, other fats, or toppings to vegetables, bread, rice, or other foods by the consumer may be likely, but the committee was not asked to consider how WIC participants

modified WIC foods for consumption. Additionally, because the committee was charged to consider foods that are readily available in the marketplace, this review will not consider foods under development, nor recommend the development of new foods. Finally, changes to USDA-FNS programs that are linked to the WIC food package but are fiscally independent (e.g., farmers’ markets) are considered for context, but no changes to the functions of such programs will be suggested in phase II.

This report contains only findings and conclusions, which are summarized in Chapter 11. It does not make recommendations. However, the committee was tasked with developing a preliminary list of priority nutrients and food groups that could be used to address nutritional deficits in the WIC population (Tables 11-1a, 11-1b, 11-2, and 11-3). To help with subsequent phase II activities and based on evidence reviewed in this report, the committee developed criteria and a proposed process to use during its phase II evaluation of the current WIC food packages, also described in Chapter 11.

Organization of This Report

In addition to introducing the charge to the committee and the rationale for this report, this first chapter considers demographic, administrative, and food system and dietary changes, including changes in national dietary guidance, that have occurred since the previous IOM committee proposed revisions to the WIC food packages (IOM, 2006).

Chapter 2 illustrates the diversity of the WIC population and complexity of behavioral and environmental factors that influence participation in WIC and consumption of items in the WIC food packages. The chapter also considers how challenges to administering WIC food packages at both state and local levels can affect the WIC participant experience.

Chapter 3 describes the committee’s approach to collecting and evaluating the range of evidence available to address its task. In addition to searching and reviewing published literature, conducting data analyses, and reviewing public comments collected through an online submission system and in open sessions over the course of the study, the committee gathered evidence from the IOM and government reports on other nutrition assistance programs, childhood obesity, weight gain during pregnancy, food security, and Dietary Reference Intakes. Also included in Chapter 3 is a discussion of challenges the committee faced when evaluating WIC-specific data. This chapter describes that the Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (2015 DGAC report) serves as the basis for evaluation of food intakes in phase I. In phase II, the basis for comparison will be the 2015 DGA.

As part of its phase I task, the committee was charged with assessing

both nutrient intakes and food group and subgroup intakes of the WIC and WIC-eligible populations (low-income children and pregnant, breastfeeding, or postpartum women). USDA-FNS also requested an evaluation of intakes before and after the 2009 food package changes.2 These analyses, described in Chapter 3 with results presented in Chapters 4 and 5, will support the committee’s preliminary list of nutrient and food group priorities (described in Chapter 11) for consideration during the phase II evaluation of the food packages.

Also as part of its phase I task, the committee evaluated nutrition-related health risks of particular concern for the WIC population, including inappropriate weight status, low hematocrit or hemoglobin, inappropriate growth or weight gain pattern, inappropriate nutritional practices, and general obstetrical risks. This evaluation is summarized in Chapter 6. Additionally, Chapter 6 summarizes the committee’s evaluation of food safety considerations.

As part of its phase I analysis, the committee was also tasked with analyzing breastfeeding trends and variability. Chapter 7 presents a review of breastfeeding trends in the U.S. and WIC populations, the impact of the food package on breastfeeding in WIC, and the promotion, motivation, and support of breastfeeding in WIC and low-income populations.

The 2009 revised WIC food packages were designed to accommodate a broader array of dietary needs and preferences than had been accommodated in the past. In Chapter 8, the committee considered issuance of food package III (for participants with qualifying medical conditions) and food package tailoring to accommodate other conditions, dietary needs, or dietary preferences.

In addition to considering nutrient intake (Chapter 4), food intake (Chapter 5), and health status of WIC participants (Chapter 6), the committee considered a number of other factors before developing its preliminary list of nutrient and food priorities for consideration during phase II evaluation of the food packages. Specifically, the committee reviewed the role of the WIC food packages as intended by the USDA-FNS; applicability of the 2015 DGAC report recommendations to WIC food packages; the science of functional ingredients added to foods and infant formulas in the WIC food packages; the infant formula regulatory and market landscape; choice and flexibility within the food packages; and cost considerations. The approach to considering these other factors is described in Chapter 9.

__________________

2 The analysis comparing intakes from before to after the food package changes is not presented in this report because the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) variable used to identify WIC participants was not available for the 2011–2012 release at the time the analysis was conducted. The comparison will be presented in the phase II report. Additional details are presented in Chapter 3.

In addition to its dietary intake tasks, the committee was tasked with the planning and implementation of a food expenditure analysis. Chapter 10 summarizes results of the phase I analysis illustrating the contribution of WIC foods to total household food expenditures.

Key findings from all chapters, except Chapter 3 because of its focus on methodology, are highlighted in Chapter 11. Also included in Chapter 11, and based on findings detailed in Chapters 4, 5 and 6, is the committee’s preliminary list of food groups that could be used to address nutritional deficits in the WIC population; the committee-developed set of guiding principles, or criteria, for use in its phase II study; and a proposed process, or framework, to use as a basis for decision making during phase II of the study.

DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFTS AND TRENDS IN WIC PARTICIPATION

In the 10 years since the last IOM review of the WIC food packages, the WIC population has changed in ways that reflect demographic changes across the United States. Although the U.S. population has increased 9 percent since 2005, from 296 to nearly 322 million, births have contributed minimally to this increase (USCB, 2005, 2015; CDC, 2015). Since 2007, birthrates have been declining (CDC, 2015). The greatest contributions to population growth have come from immigration, temporary and permanent residency, and other population shifts (DHS, 2014). According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the majority of growth in the U.S. population from 2000 to 2010 resulted from an increase in Hispanic and Asian populations (USCB, 2011). The 2010 American Community Survey found that 92 percent of the U.S. Hispanic population comprises 10 subgroups, with the top three being Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban (Motel and Patten, 2012).

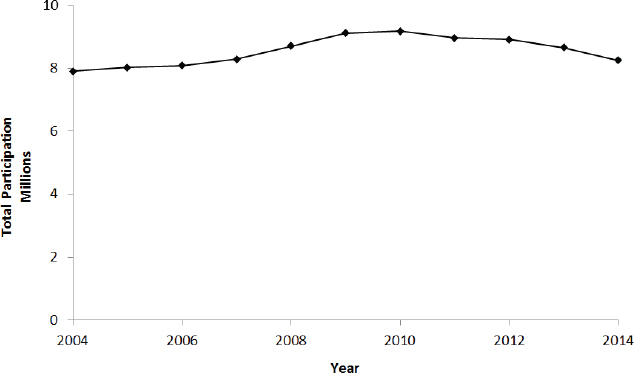

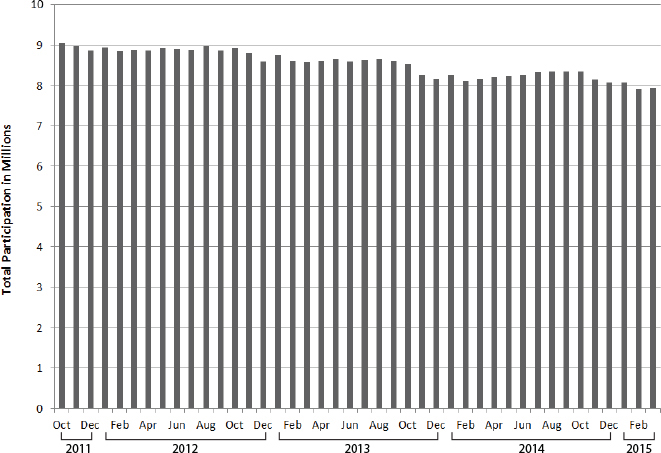

The national WIC caseload increased between 2006 and 2010 (see Figure 1-1), reaching a peak participation of approximately 9 million in 2010, and then declined to approximately 8 million participants by 2014 (USDA/ERS, 2015a). A 2014 evaluation by the USDA-Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS) found that the largest decline in WIC participation since the program’s inception occurred in fiscal year 2014, with 5 percent fewer eligible individuals participating in 2014 than in 2013 (USDA/ERS, 2015a). That declining trend has continued into 2015 (see Figure 1-2).

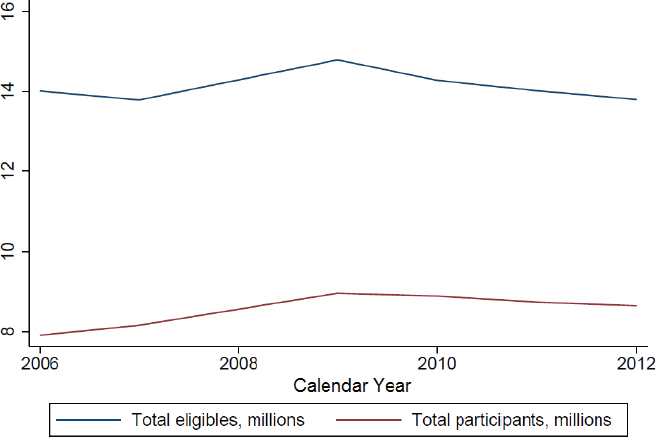

The overall decline in WIC participation may be at least partially attributed to decreasing U.S. birth rates, as well as to the nation’s improving economic health. In order to examine whether trends in WIC participation reflected changes in the population eligible for the program, analyses of the number of participants per eligible person, the number of participants, and the number of persons eligible were carried out by the committee. Data were available through 2012, and as illustrated in Figure 1-3, changes in WIC

NOTE: Fiscal year 2013 is the latest complete data. Data for fiscal year 2014 may be incomplete.

SOURCE: USDA/FNS, 2015e.

SOURCE: USDA/FNS 2015e.

SOURCES: Bitler and Hoynes, 2013; USDA/FNS, 2011b, 2013b, 2014c, 2015f.

participation through 2012 largely mirrored changes in eligibility. A number of factors in play since 2006 have likely influenced WIC participation. First, from 2007 to 2009, the United States experienced an economic downturn that was followed by a still incomplete recovery. This recession may have caused more individuals to have incomes low enough to ensure eligibility for WIC and may also have affected fertility. Second, between October 1 and 16, 2013, the federal government experienced a shutdown, which resulted in a gap in funding for the WIC program at the beginning of the fiscal year. While most states maintained WIC services, some offered modified services. Outreach was increased to communicate that services were still available. For some states, program recovery was slow, lasting up to 1 year. Finally, Medicaid, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), all of which impact WIC eligibility, experienced increases in participation during the recession and received increased funding through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (KFF, 2009, 2015; CBO, 2012; EOPUS, 2014). Since then, there have been other changes in these programs which could affect WIC eligibility and participation.

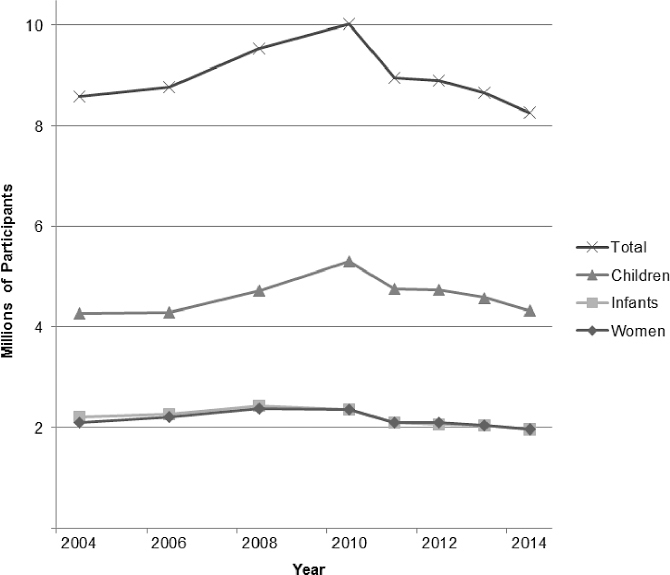

In general, the number of children in WIC has fluctuated more than the number of women and infants. Overall, more 1-year-olds than 4-year-

olds participate in the program, a trend that has been stable since 2006 (USDA/FNS, 2011a). In 2014, as the number of women and infants fell by 4 and 3 percent, respectively, the number of children fell by 6 percent (see Figure 1-4). The year 2014 marked the fourth consecutive year—and only the fourth year in the program’s history—that participation for all three groups fell (see Figure 1-4). In fact, overall expenditures in USDA nutrition assistance programs decreased 5 percent between fiscal years 2013 and 2014. During the same period, participation in SNAP and the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) decreased by 2 and 1 percent, respectively. Yet, at the same time, participation in the School Breakfast Program increased 2 percent, and the number of meals served in the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) increased 2 percent (USDA/ERS, 2015a).

NOTE: No participation data were available for 2005, 2007, or 2009.

SOURCES: USDA/FNS, 2007a, 2010, 2015f.

SOURCES: USDA/FNS, 2007a, 2013a.

SOURCES: USDA/FNS, 2007a, 2013a.

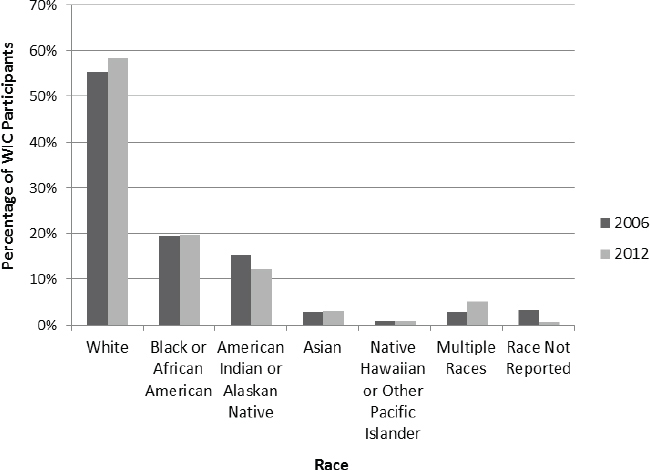

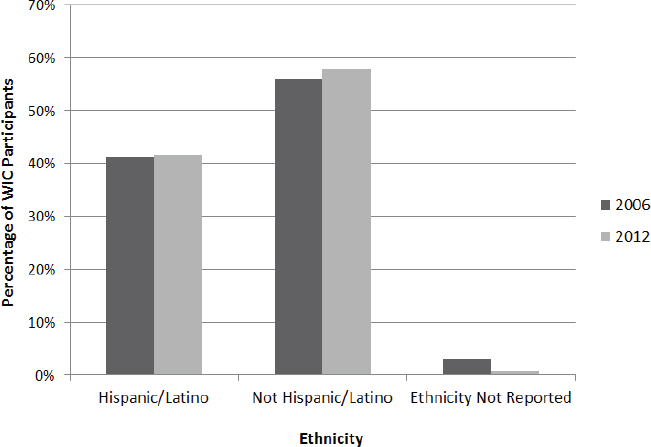

Changes in Racial and Ethnic Composition of the WIC Population

Figures 1-5a and 1-5b illustrate the racial and ethnic composition, respectively, of the WIC population in 2006 compared to 2012. Although the population remained diverse, the proportion of individuals in each category generally did not change more than 3 percent (USDA/FNS, 2007a, 2013a).

Effects of Food Package Changes on Program Participation

In addition to demographic and economic changes that may influence WIC participation, the committee considered whether food package changes implemented in 2009 may have influenced participation in the program. To do this, the committee used state-level data on participation and the number eligible for WIC from 2006 to 2012 (USDA/FNS, 2011b, 2013b, 2014c, 2015f; Bitler and Hoynes, 2013). The analysis considered the effects of national trends, time invariant state factors, the date of implementation of the new food package, the unemployment rate, births per capita and participation in TANF/SNAP/Unemployment Insurance (UI). Details of the estimation method are discussed in Appendix F. The results suggest no significant difference between participation before and participation after implementation of the new food packages. The estimated effect was not statistically significant, and it was small in magnitude.

CHANGES TO PROGRAM ADMINISTRATION

Implementation of the revised food packages in 2009 introduced not only new foods, but also the CVV,3 a new type of benefit with a specific dollar value for purchasing vegetables and fruits. States are now required to allow “split tender,” meaning participants may pay the difference out-of-pocket (or with SNAP benefits) if their vegetable and fruit purchase exceeds the amount on the CVV (USDA/FNS, 2014a). CVV redemption patterns are addressed in Chapter 9.

Since 2006, many states have also undergone significant changes to their management information systems. The changes typically allow states to move to newer Web-based technologies that are more efficient than older systems. Management information system changes in WIC programs and state-level administrative challenges related to those changes are addressed in Chapter 2.

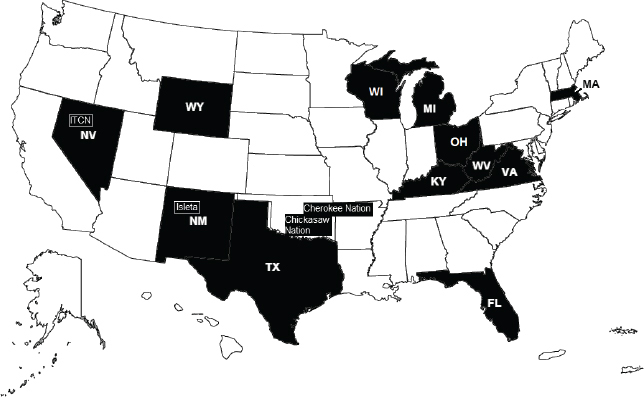

Additionally, at the time of this report, 12 states had fully implemented EBT systems (see Figure 1-6). The transition to EBT potentially changes

__________________

3 In states issuing EBT cards, the CVV is referred to as a cash value benefit (CVB).

NOTES: Isleta = Pueblo of Isleta; ITCN = Inter-Tribal Council of Nevada. Shading indicates statewide or ITO-wide WIC EBT implementation. No shading indicates states with no EBT activity or states in piloting, planning, or implementing phases.

SOURCE: Adapted from USDA/FNS, 2015g.

WIC participant food purchasing patterns by allowing more flexibility around whether and when to buy an item and the ability to purchase any foods loaded on the card at any time during the month. In contrast, the paper voucher often includes multiple eligible foods on a single voucher, which must be used in one shopping trip. The transition to EBT also creates the potential to capture data on foods purchased by allowing for the collection of specific information on exact foods redeemed and unredeemed by participants. The EBT system, however, does have some administrative trade-offs to which state agencies must adjust. State-level adoptions of WIC EBT systems are discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

Changes in Program Costs

Any changes to the food packages to be recommended by the committee during phase II of this study are required to be cost neutral so the current average food package cost (with adjustments for inflation) can be maintained. Total WIC costs, including food and nutrition services administration, were $6.3 billion in 2014, representing a decrease of almost $900 million from 2011, when total costs were $7.2 billion. Average per

participant monthly food costs have also declined, to $43.65 in 2014, from $46.69 in 2011 (see Table 1-2). As with all federal programs, unspent funds revert back to the federal government.

Major cost savings are made available to the WIC program through the infant formula rebate system. WIC state agencies are required to award infant formula rebate contracts competitively and grant winning infant formula manufacturers exclusive rights to provide formula to WIC participants in exchange for substantial discounts on infant formula and sometimes food (USDA/ERS, 2013). The total dollar value of rebates received from infant formula manufacturers by WIC state agencies in fiscal year 2014 was $1.8 billion, an increase of about $124 million since 2012, when $1.69 billion in rebates were received (see Table 1-3). The USDA-FNS request that recommended WIC food package modifications be cost neutral is discussed in more detail in Chapter 9. The methodology that the committee will use during phase II to predict the cost impact of recommended changes is described in Chapter 3.

TABLE 1-2 WIC Program Costs, 2005–2014

| Year | Participation (millions) | Program Costs (millions of dollars) | Average Monthly Food Cost per Person (dollars) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food | NSA | Total | |||

| 2005 | 8,023 | 3,602.80 | 1,335.50 | 4,992.60 | 37.42 |

| 2006 | 8,088 | 3,598.20 | 1,402.60 | 5,072.70 | 37.07 |

| 2007 | 8,285 | 3,881.10 | 1,479.00 | 5,409.60 | 39.04 |

| 2008 | 8,705 | 4,534.00 | 1,607.60 | 6,188.80 | 43.40 |

| 2009 | 9,122 | 4,640.90 | 1,788.00 | 6,471.60 | 42.40 |

| 2010 | 9,175 | 4,561.80 | 1,907.90 | 6,690.10 | 41.43 |

| 2011 | 8,961 | 5,020.20 | 1,961.30 | 7,178.90 | 46.69 |

| 2012 | 8,908 | 4,809.90 | 1,877.50 | 6,799.70 | 45.00 |

| 2013 | 8,663 | 4,497.10 | 1,881.60 | 6,478.60 | 43.26 |

| 2014 | 8,258 | 4,325.70 | 1,903.10 | 6,293.70 | 43.65 |

NOTES: Participation data are annual averages in millions. In addition to food and NSA (Nutrition Services and Administrative) costs, total expenditures include funds for program evaluation, Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program (fiscal year 1989 onward), special projects, and infrastructure. Nutrition Services includes nutrition education, preventative and coordination services (such as health care), and promotion of breastfeeding and immunization. Fiscal year 2014 data are preliminary; all data are subject to revision.

SOURCE: USDA/FNS, 2015e.

TABLE 1-3 WIC Infant Formula and Food Rebates, 2005–2014

| Fiscal Year | Rebates (millions of dollars) |

|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,709.77 |

| 2006 | 1,774.95 |

| 2007 | 1,902.74 |

| 2008 | 2,006.80 |

| 2009 | 1,937.42 |

| 2010 | 1,692.04 |

| 2011 | 1,314.10 |

| 2012 | 1,688.17 |

| 2013 | 1,876.85 |

| 2014 | 1,812.34 |

NOTES: Data for 2008–2011 are rebates billed during the fiscal year. Data for 2012–2014 are rebates received during a fiscal year. Values reflect rebates on infant formula and, to a lesser extent, infant food.

SOURCES: USDA/FNS, 2015e (years 2008–2014); Personal communication, V. Oliveira, USDA-ERS, July 23, 2014 (years 2005–2007).

CHANGES IN FOOD SYSTEMS, DIETARY PATTERNS, AND DIETARY GUIDANCE

In addition to WIC participant demographic and program administrative changes that have occurred since the 2006 committee issued its recommendations, the current committee examined the increasing focus on environmentally sustainable and local food systems; shifts in American dietary patterns; and updates in federal dietary guidance.

Changes in Food Systems

Since the publication of the 2006 IOM report, national focus on the impact of food production and consumption on environmental sustainability and long-term food security has increased. The 2015 DGAC report devoted two of seven chapters of the report to food environment and food sustainability and found consistent evidence that plant-based diets are associated with lower environmental impact (USDA/HHS, 2015). Additionally, the 2015 DGAC report reported strong evidence that the seafood industry has been rapidly expanding to meet demand and that, in contrast to past decades when fisheries collapsed because of overfishing, current fisheries are

increasingly employing sustainable management strategies to avoid long-term collapse (USDA/HHS, 2015).

There has also been growing interest in local and regional food systems. Another recent report prepared by the USDA/ERS (2015b) at the request of the House Agriculture Committee focused on trends in U.S. local and regional food systems. The report indicated that that producer participation in local food systems trended upward from 2007 to 2014, with both the value of farmers’ markets and direct-to-consumer sales of food increasing. Since 2007, the number of farmers’ markets has increased by nearly 200 percent, regional food hubs by nearly 300 percent, and school districts with farm-to-school programs by more than 450 percent (USDA/ERS, 2015b).

Changes in the Dietary Patterns of Americans

For the U.S. population overall, after decades of increases, mean energy intake decreased significantly between 2003–2004 and 2009–2010 (Ford and Dietz, 2013). Food consumption trends between 2005 and 2012 for selected food groups among women 20 years and older are presented in Table 1-4a. Whole grain consumption increased 34 percent between 2007–2008 and 2011–2012. Consumption of seafood low in omega-3 fatty acids increased by 26 percent as did consumption of nuts and seeds by 28 percent over the same time period. In contrast, consumption of soy products decreased by 30 percent. Table 1-4b presents data for children ages 2 to 5 years. For this age group, consumption of seafood high in omega-3 doubled, yogurt consumption increased by 83 percent, and whole grains increased by 46 percent between 2007–2008 and 2011–2012.

Changes in Federal Dietary Guidance

The 2006 IOM review of WIC food packages drew on the 2005 DGA (USDA/HHS, 2005). The DGA are updated every 5 years, with the most recent being the 2010 DGA. The 2015 DGA will be released prior to completion of phase II of this study. As discussed in detail in Chapter 9, phase II recommended revisions to the WIC food packages for individuals aged 2 years and older will align with the 2015 DGA. Recommendations for infants and children less than 2 years of age will draw on the recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and other authoritative groups. Because the 2015 DGA are yet to be released, analyses in Chapter 9 are based instead on the 2015 DGAC report (USDA/HHS, 2015). Changes in the 2015 DGAC report relevant to the WIC food packages are summarized below.

TABLE 1-4a Trends in Food Consumption from Selected Food Groups: Mean Intakes for U.S Women, 20 Years and Older, NHANES 2005–2012

| Food Group | Mean Intake per Day | Percent Change from Before to After the 2009 FP Changes (2007–2008 to 2011–2012) | |||

| 2005–2006 | 2007–2008 | 2009–2010 | 2011–2012 | ||

| Total fruit (c-eq) | 0.88 | 0.92 | 1.06 | 0.96 | 4 |

| Total vegetables (c-eq) | 1.48 | 1.42 | 1.46 | 1.51 | 6 |

| Whole grains (oz-eq) | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 34 |

| Refined grains (oz-eq) | 4.87 | 4.71 | 4.75 | 4.92 | 4 |

| Seafood low omega-3 (oz-eq) | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 26 |

| Seafood high omega-3 (oz-eq) | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0 |

| Eggs (oz-eq) | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 5 |

| Soy products (oz-eq) | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.07 | –30 |

| Nuts and seeds (oz-eq) | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.69 | 28 |

| Total protein foods (oz-eq) | 4.89 | 4.72 | 4.87 | 4.82 | 2 |

| Milk (c-eq) | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.70 | –7 |

| Cheese (c-eq) | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 11 |

| Yogurt (c-eq) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 17 |

| Total dairy (c-eq) | 1.51 | 1.41 | 1.50 | 1.43 | 1 |

| Oils (g-eq) | 19.20 | 19.06 | 19.92 | 22.83 | 20 |

| Solid fat (g-eq) | 33.94 | 33.02 | 30.84 | 30.64 | –7 |

| Added sugars (tsp-eq) | 14.83 | 15.80 | 15.24 | 15.37 | –3 |

NOTES: c-eq = cup-equivalents; FP = food package; g-eq = gram-equivalents; oz-eq = ounce equivalents; tsp-eq = teaspoon-equivalents.

SOURCES: NHANES 2005–2012 (USDA/ARS, 2005–2012); USDA/ARS, 2014.

Food Group Intakes

Compared to the 2005 DGA (see Table 1-5), the 2010 DGA reorganized the vegetable food group into five subgroups. The recommended food intakes increased for “red-orange vegetables,” “starchy vegetables,” and “beans and peas.” The recommended quantities of “dark green vegetables” and “other vegetables” decreased. There were no changes in recommended intakes of

TABLE 1-4b Trends in Food Consumption from Selected Food Groups: Mean Intakes for U.S. Children, 2 to 5 Years of Age, NHANES 2005–2012

| Food Group | Mean Intake per Day | Percent Change from Before to After the 2009 FP Changes (2007–2008 to 2011–2012) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2006 | 2007–2008 | 2009–2010 | 2011–2012 | ||

| Total fruit (c-eq) | 1.38 | 1.49 | 1.46 | 1.41 | –5 |

| Total vegetables (c-eq) | 0.74 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.66 | –6 |

| Whole grains (oz-eq) | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 46 |

| Refined grains (oz-eq) | 4.20 | 4.05 | 4.03 | 4.41 | 9 |

| Seafood low omega-3 (oz-eq) | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 18 |

| Seafood high omega-3 (oz-eq) | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 100 |

| Eggs (oz-eq) | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.32 | –6 |

| Soy products (oz-eq) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0 |

| Nuts and seeds (oz-eq) | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 21 |

| Total protein foods (oz-eq) | 2.86 | 2.90 | 3.00 | 2.90 | 0 |

| Milk (c-eq) | 1.63 | 1.67 | 1.70 | 1.62 | –3 |

| Cheese (c-eq) | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 14 |

| Yogurt (c-eq) | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 83 |

| Total dairy (c-eq) | 2.18 | 2.23 | 2.38 | 2.30 | 3 |

| Oils (g-eq) | 13.83 | 13.23 | 13.03 | 15.00 | 13 |

| Solid fat (g-eq) | 29.21 | 29.88 | 28.96 | 29.77 | 0 |

| Added sugars (tsp-eq) | 13.72 | 12.96 | 12.45 | 12.92 | 0 |

NOTES: c-eq = cup-equivalents; g-eq = gram-equivalents; oz-eq = ounce equivalents; tsp-eq = teaspoon-equivalents.

SOURCES: NHANES 2005–2012 (USDA/ARS, 2005–2012); USDA/ARS, 2014.

total fruit, grains, protein foods, or oils. Recommended intakes of dairy foods were slightly increased for two calorie levels.

Compared to the 2010 DGA, the 2015 DGAC report included no changes to the recommended amounts from each of the major food groups or food subgroups, except for small changes to the subgroups of protein foods. One notable change was the specification of calories from saturated

TABLE 1-5 USDA Food Intake Patterns for Kcal Levels of Interest: Comparison of 2005 DGA and 2015 DGAC Report

| Food group | Kcal Pattern Represented | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 1,200 | 1,400 | 2,200a | |||||

| 2005 | 2015 | 2005 | 2015 | 2005 | 2015 | 2005 | 2015 | |

| Fruits (c-eq/d) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1½ | 1½ | 2 | 2 |

| Vegetables (c-eq/d) | 1 | 1 | 1½ | 1½ | 1½ | 1½ | 3 | 3 |

| Dark green (c-eq/wk) | 1 | ½ | 1½ | 1 | 1½ | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Red-orange (c-eq/wk) | ½ | 2½ | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Dry beans and peasb (c-eq/wk) | ½ | ½ | 1 | ½ | 1 | ½ | 3 | 2 |

| Starchy (c-eq/wk) | 1½ | 2 | 2½ | 3½ | 2½ | 3½ | 6 | 6 |

| Other (c-eq/wk) | 4 | 1½ | 4½ | 2½ | 4½ | 2½ | 7 | 5 |

| Grains (oz-eq/d) | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 |

| Whole grains (oz-eq/d) | 1½ | 1½ | 2 | 2 | 2½ | 2½ | 3½ | 3½ |

| Other grains (oz-eq/d) | 1½ | 1½ | 2 | 2 | 2½ | 2½ | 3½ | 3½ |

| Protein Foods (oz-eq/d)c | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Meat, poultry, eggs (oz-eq/wk) | 10 | 14 | 19 | 28↓ | ||||

| Seafood (oz-eq/wk) | 3 | 4 ↓ | 6 | 9 | ||||

| Nuts, seeds, soy (oz-eq/wk) | 2 ↑ d | 2 | 3 | 5 ↑ | ||||

| Dairy (c-eq/d) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2½ | 2 | 2½ | 3 | 3 |

| Oils (g/d) | 15 | 15 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 29 | 29 |

| Limits for: | ||||||||

| Solid fats (g/d)e | 10 | 7 | 7 | 18 | ||||

| Added sugars (g/d)e | 17 | 12 | 13 | 32 |

NOTES: c-eq = cup-equivalents; DGA = Dietary Guidelines for Americans, oz-eq = ounce-equivalents.

a Food patterns for the 2,200 kcal diet were applied to women in this report because this is equivalent to the mean Estimated Energy Expenditure (EER) calculated for women reporting WIC participation in NHANES 2005–2008.

b In the USDA food patterns, dry beans and peas are first counted toward the protein foods group until recommendations for that group are met, then are counted toward the dry beans and peas vegetable subgroup (USDA, 2015).

c In 2005, key protein sources were categorized as “lean meats and beans,” without protein subgroups.

d An arrow indicates that the recommended food group amount changed from 2010 to 2015 by 1 unit in the specified direction. Other food pattern amounts are the same in the 2015 DGAC report as those recommended in the 2010 DGA.

e In 2005, solid fats and added sugars were built into a “discretionary calorie allowance” instead of specific gram levels of intake.

SOURCES: USDA/HHS, 2005, 2010, 2015.

fats and added sugars, which was given as a single percentage of total energy intake in the 2010 DGA. In the 2015 DGAC report, limits were given separately for solid fats and for added sugars. The implication is that energy from these two dietary components is not interchangeable. As a result, low intake of one does not imply that a higher intake of the other would be appropriate.

The food patterns in the 2010 DGA included templates for several variations in the USDA Food Pattern, including the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Eating Plan, and Mediterranean, vegetarian, and vegan patterns. The 2015 DGAC report included a healthy U.S.style, healthy Mediterranean, and healthy vegetarian patterns (USDA/HHS, 2015).

Nutrient Intakes

The 2015 DGAC report identified nine nutrients (vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin C, folate, calcium, magnesium, fiber, and potassium) as “shortfall” nutrients, that is, nutrients that are under-consumed relative to Dietary Reference Intake recommendations (see Table 1-6). For adolescent and premenopausal females, iron was also identified as a shortfall nutrient because of risk of iron deficiency. Within the larger category of shortfall nutrients, calcium, vitamin D, fiber, and potassium were classified as nutrients of public health concern because their under-consumption has been linked to adverse health outcomes. The 2015 DGAC report continues to recommend that women of reproductive age supplement a diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and grains with foods enriched with folic acid or with folic acid supplements. Compared to the 2010 DGAC report, the 2015 DGAC report no longer identified choline and vitamin K in adults, phosphorus in children, and vitamin B12 in adults older than 50 as shortfall nutrients. Folate, which was categorized as a nutrient of concern for women capable of becoming pregnant in the 2010 DGA, was categorized as a shortfall nutrient in the 2015 DGAC report. Iron was still considered a nutrient of public health concern for these women.

Food Components to Reduce

Both the 2010 DGA and 2015 DGAC report focus on limiting added sugars in the diet, and the 2015 DGAC report recommended limiting added sugars to no more than 10 percent of total calories. The 2015 DGAC report also retained the 2010 DGA recommendation to limit saturated fat to 10 percent of total calories. The 2010 DGA recommendation to limit cholesterol was not retained.

The 2010 DGA recommended that adults up to 50 years of age limit

TABLE 1-6 Shortfall Nutrients and Nutrients of Public Health Concern from the Reports of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committees: 2005, 2010, and 2015

| 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | |||

| Calcium | |||

| Potassium | |||

| Choline | |||

| Fiber | |||

| Magnesium | |||

| Vitamin A | |||

| Vitamin C | |||

| Vitamin E | |||

| Vitamin D | |||

| Vitamin K | |||

| Folate | |||

| Children and Adolescents | |||

| Calcium | |||

| Potassium | |||

| Fiber | |||

| Magnesium | |||

| Phosphorus | |||

| Vitamin A | |||

| Vitamin C | |||

| Vitamin E | |||

| Vitamin D | |||

| Women of Reproductive Age | |||

| Iron | |||

| Folate | |||

NOTES: ![]() = shortfall nutrient;

= shortfall nutrient; ![]() * = nutrient of public health concern; nutrients of public health concern are those shortfall nutrients that are linked to adverse health outcomes.

* = nutrient of public health concern; nutrients of public health concern are those shortfall nutrients that are linked to adverse health outcomes.

SOURCES: USDA/HHS, 2005, 2010, 2015.

their sodium intake to 2,300 mg per day and that those who are 51 years and older, African American, or with hypertension, diabetes, or chronic kidney disease limit sodium intake to 1,500 mg daily. The 2015 DGAC report recommended a sodium limit of 2,300 mg per day for all adults.

Dietary Guidance for Infants and Children Up to 2 Years of Age

Since the 2006 IOM report, minor updates have been made to dietary guidance for individuals less than 2 years of age. In 2008, the AAP issued guidance recommending reduced-fat milks for children over the age of 1 for whom overweight or obesity is a concern (AAP, 2008). As denoted in the final rule, USDA-FNS permits the issuance of reduced-fat milks for children 1 year of age and over who fall into this category (USDA/FNS, 2014a). Also in 2008, the AAP published a statement reporting insufficient data to document a protective effect of any dietary intervention on allergy development beyond 4 to 6 months of age (Greer et al., 2008). Results of the committee’s review of changes in dietary guidance for infants and children up to 2 years of age and its implications for WIC food packages is described in Chapter 9.

Proportion of Recommended Food Groups Supplied by WIC Foods

As its name implies, WIC was designed to be a supplemental food program. In this context, supplemental foods are

those foods containing nutrients determined by nutritional research to be lacking in the diets of pregnant, breastfeeding, and postpartum women, infants, and children, and foods that promote the health of the population served by the WIC program as indicated by relevant nutrition science, public health concerns, and cultural eating patterns, as prescribed by the Secretary.4

The term supplemental is not quantified in a regulatory context, but the term implies provision of less than 100 percent of what is needed, with specific focus on provision of foods that address shortfall nutrients, including nutrients of public health concern.

Given the WIC program objective to supplement participants’ usual diets, it is useful to know the potential contribution of the WIC food packages to USDA-recommended food group intakes (USDA/HHS, 2015). Table 1-7 shows the proportion of each USDA major food group and subgroup supplied to an individual by a monthly food package if consumed in maximum amounts.

Although Table 1-7 was created by applying a 1,300 kcal weighted

__________________

4 95th Congress. 1978. Public Law 95-627, § 17: Child care food program.

food pattern for children equivalent to 1,225 kcal per day and 2,2005 kcal per day for women using the 2015 DGAC report food patterns (USDA/HHS, 2015), the WIC food packages serve individuals with a wide range of energy needs. The data presented in the table are therefore only approximations of the proportion of food intake needs contributed by the WIC food package, assuming full redemption and consumption. As shown in the table, for children, WIC foods provide approximately 77, 36, 90, 55, and 60 percent of the recommended intakes for fruits, vegetables, dairy, grains, and protein, respectively. For pregnant and partially breastfeeding women, the food packages provide approximately 57, 19, 98, 25, and 47 percent of the recommended intakes for those same food groups.

__________________

5 To evaluate the diets of all children 1 to less than 5 years of age in this report, the committee applied a weighted food pattern (a 1,000 kcal pattern weighted 1:3 with the average of 1,200- and 1,400-kcal patterns) as was applied in IOM (2011). The Estimated Energy Expenditure (EER) analysis conducted for this report indicated a mean EER for WIC women of approximately 2,200 kcals.

TABLE 1-7 Percentage of the Recommended Servings from the 2015 USDA Food Patterns Supplied by the Current Maximum Allowances for the WIC Food Packages by Category of Participant

| WIC Food Category | USDA Food Pattern Group | Units/Day | Children | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP IV: 1 to 4 Years | |||||

| WIC Max | % of DGAC Report Rec | DGAC 1,300 Kcal Food Patterna | |||

| Total fruit | Fruits | c-eq | 0.9 | 77 | 1.2 |

| Juice, 100%c | Fruit (juice only) | c-eq | 0.5 | 107 | 0.5 |

| Fruitd | Fruit, fresh | c-eq | 0.4 | 57 | 0.7 |

| Total vegetables | Total vegetables | c-eq | 0.5 | 36 | 1.4 |

| Vegetablese | c-eq | 0.3 | 21 | 1.4 | |

| Dry legumes | Dry beans and peas | c-eq | 0.3 | 353 | 0.1 |

| Total dairy | Dairy | c-eq | 2.1 | 90 | 2.4 |

| Milkf | c-eq | 2.1 | 90 | 2.4 | |

| Cheeseg | oz-eq | 0.0 | 0 | 2.4 | |

| Total grains | Grains | oz-eq | 2.3 | 55 | 4.1 |

| Breakfast cereal | oz-eq | 1.2 | 29 | 4.1 | |

| Whole wheat breadh | oz-eq | 1.1 | 26 | 4.1 | |

| Total proteini | Total protein foods | oz-eq | 1.9 | 60 | 3.1 |

| Dry legumesj | Dry beans and peas | oz-eq | 0.3 | NR | NR |

| Peanut butterk | Nuts, seeds, and soy | oz-eq | 1.2 | 354 | 0.3 |

| Eggs | Meat, poultry, eggs | oz-eq | 0.4 | 19 | 2.1 |

| Fish | Seafood | oz-eq | 0.0 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP V: Pregnant and Partially BF, Up to 1 Year PP | FP VI: Up to 6 Months PP | FP VII: Fully BF, Up to 1 Year PP | ||||

| WIC Max | % of DGAC Report Rec | WIC Max | % of DGAC Report Rec | WIC Maximum Allowance | % of DGAC Report Rec | DGAC 2,200 Kcal Food Patternb |

| 1.1 | 57 | 0.9 | 47 | 1.1 | 57 | 2.0 |

| 0.6 | 91 | 0.4 | 61 | 0.6 | 91 | 0.7 |

| 0.5 | 40 | 0.5 | 40 | 0.5 | 40 | 1.3 |

| 0.6 | 19 | 0.6 | 19 | 0.6 | 19 | 3.0 |

| 0.4 | 13 | 0.4 | 13 | 0.4 | 13 | 3.0 |

| 0.3 | 88 | 0.3 | 88 | 0.3 | 88 | 0.3 |

| 2.9 | 98 | 2.1 | 71 | 3.6* | 118* | 3.0 |

| 2.9 | 98 | 2.1 | 71 | 3.2 | 107 | 3.0 |

| 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.4* | 8* | 4.5 |

| 1.7 | 25 | 1.7 | 25 | 1.2* | 17* | 7.0 |

| 1.2 | 17 | 1.2 | 17 | 1.2 | 17 | 7.0 |

| 0.5 | 8 | 0.5 | 8 | 0.0* | 0.0* | 7.0 |

| 1.9 | 31* | 1.9 | 31* | 3.3 | 54* | 6.0* |

| 0.3 | NR | 0.3 | NR | 0.3 | NR | NR |

| 1.2 | 168 | 1.2 | 168 | 1.2 | 168 | 0.7 |

| 0.4 | 10 | 0.4 | 10 | 0.8 | 20 | 4.0 |

| 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 1.0 | 78 | 1.3 |

NOTES: * Denotes material updated after report’s initial release. BF = breastfeeding; c-eq = cup-equivalents; DGAC = Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee; FP = food package; NR = no recommendation; oz-eq = ounce-equivalents; P = pregnant; PP = postpartum; Rec = recommendation; WIC Max = WIC maximum allowance.

a The food pattern recommendation for children ages 1 to less than 5 years was created by using the 1,000 kcal pattern and the average of the 1,200 and 1,400 kcal pattern (Table D1.10 of USDA/HHS, 2015), weighted in a 1:3 ratio as per the method of IOM, 2011.

b A 2,200 kcal food pattern was applied to women based on the mean Estimated Energy Expenditure of WIC women respondents from NHANES 2005–2008, calculated assuming the second trimester of pregnancy and low-active physical activity level (Table D1.10 of USDA/HHS, 2015; IOM, 2005).

c The maximum allowance of juice provided to children equates to 4 ounces per day, which is on the lower end of the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation of 4 to 6 ounces per day (AAP, 2001). Although the 2015 DGAC report does not specify a juice recommendation for adults, in this table 33 percent of fruit intake is allotted to 100% juice, according to the DGAC’s finding that 33 percent of fruit intake comes from fruit juice in the overall U.S. population (USDA/HHS, 2015).

d To determine the maximum allowance, a composite of fruits purchased was developed using percentage of total food group intake data (supporting Appendix E-2 of the 2015 DGAC report; Personal communication, P. Britten, 2015). Fruits contributing to 5 percent or more of intake were included in their respective proportions and matched to 2014 price data. Only fresh fruit was included as all states allow fresh forms. Fifty percent of the cash value voucher (CVV) was assumed ($4 for children and $5.5 for women, respectively).

e To determine the maximum allowance, a composite of vegetables was developed using the percentage of total food group intake data (supporting Appendix E-2 of the 2015 DGAC report; Personal communication, P. Britten, 2015). Vegetables contributing to 5 percent or more of intake in each subgroup were included in their respective proportions and matched to 2014 price data. Only fresh vegetables were included as all states allow fresh forms. Fifty percent of the CVV was assumed ($4 for children and $5.5 for women, respectively).

f Milk was selected to represent the maximum allowance for this WIC food category as it allows for the largest number of dairy servings per day. Substitutions may include soy milk, cheese, or tofu. In the USDA food patterns, tofu is categorized as a dietary contributor to the protein group.

g For package VII, milk and cheese provided in WIC are added together to compare to the USDA dairy food group; 1.5 oz of natural cheese = 1 serving-equivalent of dairy.

h Whole wheat bread was selected to represent the maximum allowance for this WIC food category as it allows for the same number of grains servings per day as other possible substitutions. The Grains category here includes both whole wheat bread and breakfast cereals. Substitutions include brown rice, bulgur, oatmeal, barley, tortillas, or whole wheat pasta.

i Note that in packages IV and VI, legumes or peanut butter can be selected. Total protein for these packages as presented in the table includes peanut butter and not legumes because peanut butter is more regularly purchased (USDA food package options report). In packages V and VII, both are provided; therefore, total protein includes legumes plus peanut butter.

j Legumes were considered a protein substitution (in addition to a vegetable option) as it alternates with peanut butter, another protein source, in the food packages. If considered a contributor to vegetable intake, the contribution would be 21 percent and 10 percent of the 2015 DGAC report recommendations for vegetable intake for children and women, respectively.

k 0.5 ounces of peanut butter = 1 ounce-equivalent serving of nuts, seeds, and soy.

SOURCES: USDA/FNS, 2014a; USDA/HHS, 2015; Personal communication, P. Britten, USDA/CNPP, December 9, 2014.

REFERENCES

AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics). The use and misuse of fruit juice in pediatrics. 2001. Pediatrics 107(5):1210-1213.

AAP, Committee on Nutrition. 2008. Lipid screening and cardiovascular health in childhood. Pediatrics. 122(1):198-208.

Bitler, M., and H. Hoynes. 2013. The more things change, the more they stay the same? The safety net and poverty in the great recession. Journal of Labor Economics. Published electronically September 2013. doi:10.3386/w19449.

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). 2012. The supplemental nutrition assistance program. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/04-19-SNAP.pdf (accessed August 24, 2015).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2015. National vital statistics system: Birth data. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/births.htm (accessed August 24, 2015).

DHS (U.S. Department of Homeland Security). 2014. 2013 Yearbook of immigration statistics. Washington, DC: DHS. http://www.dhs.gov/publication/yearbook-2013 (accessed August 24, 2015).

EOPUS (Executive Office of the President of the United States). 2014. The economic impact of the American recovery and reinvestment act five years later: Final report to Congress. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President of the United States. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/cea_arra_report.pdf (accessed August 24, 2015).

Ford, E. S., and W. H. Dietz. 2013. Trends in energy intake among adults in the United States: Findings from NHANES. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 97(4):848-853.

Greer, F. R., S. H. Sicherer, A. W. Burks, and American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. 2008. Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: The role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics 121(1):183-191.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2014. Healthy people 2020: Maternal, infant, and child health objectives. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives (accessed June 1, 2015).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2005. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2006. WIC food packages: Time for a change. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011. Child and adult care food program. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2015. Review of WIC Food Packages: An evaluation of white potatoes in the cash value voucher: Letter report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

KFF (The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation). 2009. A foundation for health reform: Findings of a 50 state survey of eligibility rules, enrollment and renewal procedures, and cost-sharing practices in Medicaid and CHIP for children and parents during 2009. Washington, DC: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8028.pdf (accessed August 24, 2015).

KFF. 2015. Medicaid financing: How does it work and what are the implications? Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-medicaid-financing-how-does-it-work-and-what-are-the-implications (accessed August 24, 2015).

Motel, S., and E. Patten. 2012. The 10 largest Hispanic origin groups: Characteristics, rankings, top counties. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

NWA (National WIC Association). 2013. The role of WIC in public health. Washington, DC: National WIC Association. https://s3.amazonaws.com/aws.upl/nwica.org/WIC_Public_Health_Role.pdf (accessed August 24, 2015).

USCB (U.S. Census Bureau). 2005. Annual estimates of the population for the United States and states, and for Puerto Rico: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2005. http://www.census.gov/popest/data/state/totals/2005/tables/NST-EST2005-01.xls (accessed October 28, 2015).

USCB. 2011. Overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2011/dec/c2010br-02.pdf (accessed July 9, 2015).

USCB. 2015. Population clock. http://www.census.gov (accessed August 24, 2015).

USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture). 2015. Beans and peas are unique foods. (http://www.choosemyplate.gov/vegetables-beans-and-peas) (accessed August 27, 2015).

USDA/ARS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service). 2005–2012. What we eat in America, NHANES 2005–2012. Beltsville, MD: USDA/ARS. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/wweia.htm (accessed December 15, 2014).

USDA/ARS. 2014. Food patterns equivalents database data tables. http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=23868 (accessed August 24, 2015).

USDA/ERS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Economic Research Service). 2009. The WIC program: Background, trends, and economic issues, 2009 edition. Washington, DC: USDA/ERS. http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/159295/err73.pdf (accessed March 2, 2015).

USDA/ERS. 2013. Trends in infant formula rebate contracts: Implications for the WIC program. Washington, DC: USDA/ERS. http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1236572/eib119.pdf (accessed October 5, 2015).

USDA/ERS. 2015a. The food assistance landscape FY 2014 annual report. Washington, DC: USDA/ERS. http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1806461/eib137.pdf (accessed June 22, 2015).

USDA/ERS. 2015b. Trends in U.S. local and regional food systems. Washington, DC: USDA/ERS. http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1763057/ap068.pdf (accessed June 10, 2015).

USDA/FNS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Food and Nutrition Service). 2007a. WIC participant and program characteristics 2006. Alexandria, VA: USDA/FNS. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/pc2006.pdf (accessed July 8, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2007b. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC): Revisions in the WIC food packages; interim rule, 7 C.F.R. § 246.

USDA/FNS. 2010. WIC participant and program characteristics 2008. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/pc2008_0.pdf (accessed April 2, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2011a. WIC participant and program characteristics 2010. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/WICPC2010.pdf (accessed October 29, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2011b. National and state-level estimates of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) eligibles and program reach, 2000–2009. (accessed August 31, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2012. National survey of WIC participants II: Volume 1: Participant characteristics (final report). Washington, DC: USDA/FNS. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/NSWP-II.pdf (accessed April 13, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2013a. WIC participant and program characteristics 2012 final report. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/WICPC2012.pdf (accessed December 20, 2014).

USDA/FNS. 2013b. National and state-level estimates of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) eligibles and program reach, 2010. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/WICEligibles2010Vol1.pdf (accessed August 24, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2014a. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC): Revisions in the WIC food packages; final rule, 7 C.F.R. § 246.

USDA/FNS. 2014b. WIC policy memorandum #2014-6: Final WIC food package rule: Implementation of lowfat (1 percent) and nonfat milks provision.

USDA/FNS. 2014c. National and state-level estimates of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) eligibles and program reach, 2011, volume i. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/WICEligibles2011Volume1.pdf (accessed May 22, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2015a. Frequently asked questions about WIC. http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/frequently-asked-questions-about-wic (accessed May 22, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2015b. About WIC—WIC at a glance. http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/about-wic-wic-glance (accessed May 22, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2015c. WIC policy memorandum #2015-3 to WIC state agency directors: Eligibility of white potatoes for purchase with the cash value voucher.

USDA/FNS. 2015d. WIC policy memorandum #2015-4 to WIC state agency directors: Increase in the cash value voucher for pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding women.

USDA/FNS. 2015e. WIC program (website). http://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program (accessed July 13, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2015f. National and state-level estimates of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) eligibles and program reach, 2012, volume i. Alexandria, VA: USDA/FNS. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/ops/WICEligibles2012-Volume1.pdf (accessed August 24, 2015).

USDA/FNS. 2015g. WIC EBT activities. http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/wic-ebt-activities (accessed November 4, 2015).

USDA/HHS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2005. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/document/pdf/DGA2005.pdf (accessed December 15, 2014).

USDA/HHS. 2010. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010. http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2010/dietaryguidelines2010.pdf (accessed December 15, 2014).

USDA/HHS. 2015. The report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015, to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientificreport/PDFs/Scientific-Report-of-the-2015-Dietary-Guidelines-Advisory-Committee.pdf (accessed May 24, 2015).