11

Findings and Conclusions

In response to its charge, the committee used evidence gathered from a range of sources, including a comprehensive literature review as well as targeted searches, government reports, workshops, on-site observations of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) activities, and data analyses to develop the findings that are summarized in this chapter. The committee’s conclusions from these findings were then used to establish a set of evaluative criteria and a framework to underpin the activities to be carried out in phase II and to guide the development of the committee’s recommendations.

FINDINGS

The committee’s findings are organized by chapter, with the exception of Chapter 3, “Approach to the Task,” which covers the methods applied in this report and does not have findings.

Chapter 1

In Chapter 1 the committee reviewed the background and goals of the WIC program, as well as changes in the WIC population, WIC program administration, and changes to dietary patterns of the U.S. population and federal dietary guidance that have occurred since the 2006 review of WIC food packages. The key findings from the committee’s review of this evidence are as follows:

- The committee found that enrollment in WIC was stable up to 1 year after initial implementation of the 2009 food package changes; however, full implementation took place over several years during which further alterations to the food packages were made.

- The decline in WIC participation after 2010 may have resulted from several national economic and demographic changes, which include a short-term decline in U.S. birth rate, changes in the U.S. economy, the 2013 federal government shutdown, and changes in the maximum benefit levels for other food assistance programs.

- The 2009 changes in the food packages were based on Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations and options allowed in the final rule. These changes resulted in variability across states when the new food packages were actually implemented.

- WIC serves a population with a diverse racial and ethnic composition, and this composition has not changed appreciably since the 2006 IOM review of WIC food packages.

- Transitioning WIC benefits to the electronic benefit transfer (EBT) system is expected to improve participant flexibility in redeeming WIC foods. EBT should also allow for improved data collection on redemption patterns of WIC foods.

- The committee found that the nine shortfall nutrients (vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin C, folate, calcium, magnesium, fiber, and potassium for the general U.S. population as well as iron as a shortfall nutrient for adolescent and premenopausal females) identified in the Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (2015 DGAC report) should be considered in phase II. Four of these shortfall nutrients, calcium, vitamin D, fiber, and potassium, were also identified as nutrients of public health concern.

- In contrast to the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA), the 2015 DGAC report provided separate limits for intake of energy from saturated fats and added sugars, implying that energy from these two dietary components are not interchangeable.

- The WIC food packages supplement the diets of women and children with smaller proportions of some foods than others relative to the amounts recommended in the 2015 DGAC report for 2,200 and 1,300 kcal food patterns, respectively.

Chapter 2

In Chapter 2, the committee reviewed factors that affect the WIC participant experience, including barriers to participation and redemption,

availability and access to foods, and administrative and vendor challenges associated with implementing the WIC food packages. The key findings from this evidence are as follows:

- Few studies have examined the cultural food preferences, feeding practices, or feeding styles of WIC participants.

- Although multiple studies have documented moderate to high satisfaction with the 2009 changes in the WIC food packages, evidence also indicates cultural variation in participants’ satisfaction with certain types or amounts of food items.

- There were cultural differences in how young children are fed, but it was not possible to ascertain whether the WIC food packages were aligned with these feeding behaviors.

- There were racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration.

- Barriers and incentives to WIC participation and benefit redemption were identified in the literature reviewed. However, the quantitative evidence was insufficient to support a causal relationship between these barriers and participation in the program.

- Strategies from the field of behavioral economics may be promising when considering incentives to promote WIC participation and benefit redemption.

- More than 90 percent of WIC participants primarily redeem their WIC benefits at supercenter-type stores or supermarkets.

- Although there are challenges in the implementation of EBT, where implementation is complete, EBT has been positively received by WIC participants, state and local agencies, and the vendor community.

- EBT data suggest that redemption varies among the different WIC foods. Relatively high redemption rates of fruits and vegetables suggest that the cash value voucher (CVV) is well utilized.

- The final rule specified the required foods in the package, but options allowed within many food categories have permitted states to authorize a wider variety of options on state food lists.

- Available evidence suggests that a wider variety of foods were available from WIC vendors to meet the package requirements after the 2009 changes to the food packages.

- Despite administrative challenges, WIC vendors and the food industry were generally able to adapt to the 2009 interim rule and the 2014 final rule that implemented changes to food packages.

Chapter 4

In Chapter 4, the committee reviewed and analyzed evidence on nutrient intake and adequacy of WIC and low-income populations based on comparison to the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs). Analyses included a comparison between WIC participants and low-income nonparticipants before the 2009 food package changes (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES] 2005–2008), and comparison to the most recent data on intakes of WIC-eligible low-income children and women, regardless of WIC status (from NHANES 2011–2012). Unless otherwise indicated, the committee’s findings were similar across the subgroups analyzed. Data were not evaluated for breastfed infants because sample sizes were too small for this group. As described in Chapter 3, if 5 percent or more of the population had an inadequate or excessive intake1 of a nutrient in comparison to the appropriate DRI value, the committee considered intake for that nutrient to be low (or high if above the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range [AMDR] or Upper Tolerable Intake Level [UL]) in that population. If the mean intake of the population was below the Adequate Intake (AI) value for a nutrient with an AI, the committee considered intake of that nutrient to be low for that population. The key findings from these analyses are as follows:

- Across population subgroups, low-income women 19 to 50 years of age had inadequate intakes of calcium; copper; iron; magnesium; zinc; vitamins A, E, and C; thiamin; riboflavin; niacin; vitamin B6; folate; and protein compared to Estimated Average Requirements (EARs). Mean potassium, choline, and fiber intakes were below the AI.

- Across population subgroups, low-income women 19 to 50 years of age had a 21 percent prevalence of inadequate vitamin D status, as measured by serum 25(OH)D.

- Women 19 to 50 years of age who were participating in WIC had a higher prevalence of inadequacy for copper, iron, magnesium, zinc, vitamin C, thiamin, vitamin B6, and folate compared to low-income women not participating in WIC, although these differences were not statistically significant.

- Across population subgroups, low-income fully formula-fed infants 0 to less than 6 months of age consumed less than the AI for choline.

- Fully formula-fed infants ages 0 to 6 months are provided with approximately 8 mg of iron per day from formula, an amount that

__________________

1 Low intake of carbohydrate was not considered of concern. Excess intake of zinc was not considered of concern because the method used to set the UL resulted in a narrow margin between the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) and the UL.

-

falls well above the AI (0.27 mg per day) but below the UL (40 mg per day) for this nutrient and age group.

- Across population subgroups, low-income formula-fed infants 6 to less than 12 months of age had low iron intakes in comparison to the EAR, although prevalence of inadequacy was less than 10 percent across subgroups. WIC-participating infants 6 to less than 12 months of age had a lower prevalence of dietary iron inadequacy compared to income-eligible infants who were not participating in WIC, although these differences were not statistically significant.

- Across population subgroups, low-income children 1 to less than 2 years of age had a high prevalence of vitamin E intakes below the EAR, and mean intakes of potassium and fiber that were below the AI for these nutrients.

- Across population subgroups, low-income children 2 to less than 5 years of age had a high prevalence of calcium and vitamin E intakes below the EAR and mean potassium and fiber intakes below the AI.

- Children 2 to less than 5 years of age who participated in WIC had a lower prevalence of calcium inadequacy compared to income-eligible children who were not participating in WIC.

- More than 5 percent of WIC participants in specific subgroups exceeded the UL for a number of micronutrients2:

- Women ages 19 to 50 years: sodium, iron (slightly more than 5 percent of the population).

- Formula-fed infants 6 to less than 12 months: selenium.

- Children 1 to less than 2 years of age: sodium and selenium.

- Children 2 to less than 5 years of age: sodium, copper, and selenium.

- The WIC food packages aim to reduce added salt, saturated fat, and added sugars. Nonetheless, across subgroups of WIC-participating women and children, intakes of all of these nutrients were excessive.3

__________________

2 Excess zinc intakes in more than 5 percent of the population were found for formula-fed infants, children 1 to less than 2 years of age, and children 2 to less than 5 years of age. However, for the younger age groups, excess zinc intake was not considered of concern because the method used to set the UL resulted in a narrow margin between the RDA and the UL. For older children, there exists no evidence for adverse effects from zinc naturally occurring in food. Excess retinol intakes in more than 5 percent of the population were also found for formula-fed infants and children, but were not considered of concern due to a similarly narrow margin between the UL and the RDA. Toxicity from excess retinol intake is also rare (IOM, 2001).

3 Excessive energy intakes were not included as a finding because likely under- or over-reporting in dietary intake surveys (as described in Chapter 4) complicates direct comparison to the Estimated Energy Requirement (EER).

- The Nutrient-Based Diet Quality index indicated that the mean adequacy across 9 nutrients was 75 percent or less across all population groups, and only 50 percent for WIC women.

Chapter 5

Intakes of food groups and their subgroups among low-income populations were analyzed in Chapter 5, using the same population comparisons as in Chapter 4. In addition, the committee reviewed the available scientific literature for intake of foods among children less than 2 years of age. The key findings from these analyses are as follows:

- Infants are progressively exposed to a variety of food groups as they transition to complementary foods, but may not have a broad exposure on any given day.

- Introducing complementary food before 4 months of age appears to be more common among WIC-participating mothers compared to non-WIC mothers and those who do not exclusively breastfeed.4 This practice has implications for infant weight gain and for health outcomes associated with inappropriate infant weight gain.

- Estimates from the Infant Feeding Practices Study (IFPS) II suggest that approximately one-quarter of infants are introduced to cow’s milk before the time recommended (1 year of age). Cow’s milk consumption on any given day occurred in 13.3 percent of WIC infants 6 to less than 12 months of age in the 2008 Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study (FITS).

- Published national survey data suggest four areas of concern for food group intakes of infants ages 0 to 24 months: early introduction of complementary foods; low intakes of iron-rich foods, particularly meats; early introduction of cow’s milk; and consumption of desserts, sweetened beverages, and salty snacks.

- Analyses of NHANES data for low-income children ages 2 to less than 5 years and women participating in or eligible for WIC showed that:

- For most food groups and subgroups, more than half of children and women had mean intakes below amounts recommended in the 2015 DGAC report.

- Whole grains, vegetables (particularly dark green and red-orange), and seafood were the food groups with the highest

__________________

4 These data were collected prior to the 2009 food package changes, which delayed provision of complementary foods until 6 months of age.

-

-

prevalence of mean intakes below amounts recommended in the 2015 DGAC report.

- Mean intakes of solid fats and added sugars exceeded the recommended limits specified in the 2015 DGAC report for almost all children and women (87 to 100 percent).

-

- The number of low-income women in the NHANES 2011–2012 subgroups is small and distribution estimates are imprecise. This limits the ability to make population-level comparisons to recommended intake amounts. However, mean intake estimates can be compared across survey years.

- Mean total Healthy Eating Index-2010 (HEI-2010) scores for women and children were well below the maximum possible score of 100 (51.9 for WIC women and 59.8 for WIC children). For WIC participating women, scores were lowest relative to the maximum possible score for greens and beans, whole grains, fatty acids (healthy fats), seafood and plant proteins, and empty calories. Scores for WIC-participating children were low for these components as well as for total vegetables. These findings are consistent with the committee’s analysis on food group intakes.

Chapter 6

Nutrition-related health risks that are relevant to the WIC-eligible population were reviewed in Chapter 6. The key findings from this review are as follows:

- General nutrition-related concerns for women of childbearing age include the high prevalence of overweight and obesity, excessive gestational weight gain, and poor breastfeeding success related to their weight and weight gain. Moreover, excess postpartum weight retention contributes to the development and persistence of overweight and obesity.

- Iron is particularly important for pregnant and postpartum women because of the high prevalence of anemia among them, and the high amount required for optimal maternal and fetal health.

- Folate is particularly important before and early in pregnancy for prevention of neural tube defects. Published evidence indicates that folate status is low among WIC participants.

- For children, the primary nutrition-related concerns are the high prevalence of obesity and overweight, low iron status especially in children ages 1 to 3 years, and excessive intakes of added sugars and increased risk of dental caries.

- Health concerns for the WIC population have not changed substantially since the last review.

- There is some evidence to suggest that WIC has a positive effect on cognition in children, although it comes from observational studies and may be biased by self-selection into the program.

- No evidence was found to suggest concern about the safety of foods in the WIC packages.

Chapter 7

In Chapter 7, the committee reviewed the literature on the health benefits of breastfeeding; breastfeeding trends in the general U.S. and WIC populations; barriers, motivators, and incentives for breastfeeding; and the effect of the WIC breastfeeding food package on breastfeeding promotion, initiation, and duration among WIC and low-income populations. The key findings from this review are as follows:

- Literature specific to the WIC population suggests that breastfeeding (full or partial) for at least 4 months is associated with lower rates of childhood obesity.

- National data show that there has been an increase in breastfeeding among women in the general population and a parallel increase among WIC participants, although at a lower prevalence.

- Several barriers to breastfeeding were identified, including social norms, cultural factors, social structures, employment, and biomedical factors. The influence of each specific barrier on breastfeeding in the WIC population could not be determined.

- WIC participation was associated with a lower proportion of women who initiate breastfeeding and shorter durations of exclusive and any breastfeeding compared to women not participating in WIC. Evidence on the effect of timing of entry into WIC on these outcomes was not conclusive.

- Evidence suggests that breastfeeding promotion and support provided through the WIC program improve breastfeeding initiation and duration. Data are less convincing for effects of this promotion and support on exclusivity of breastfeeding.

- WIC participants may perceive that the program delivers conflicting messages by supporting breastfeeding and also distributing infant formula at no cost to participants.

- Small improvements in breastfeeding initiation were detected in some studies following the 2009 food package changes. However, it is not possible to determine whether these improvements resulted from the food package changes themselves, the enhanced breast-

feeding promotion and support activities that began at about the same time, or both.

Chapter 8

In Chapter 8, the committee considered subsets of the WIC population with unique dietary needs or food preferences, including the medically fragile, individuals with food allergies or intolerances, and those with unique dietary practices. The key findings from this review are as follows:

- Food package III is critical to WIC participants, but providing the full food package in addition to the special foods/formula may be inappropriate for participants’ conditions or may exceed their needs for supplementary food.

- Food allergies among children increased approximately 50 percent between 1997 and 2011. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Academy of Allergy recommend that infants be breastfed for 4 to 6 months to prevent food allergies and that the introduction of solid foods, whether they are potentially allergenic or not, should not be delayed beyond 4 to 6 months.

- The current food packages allow substitutions for most allergenic foods but not for eggs and fish. Nearly half of states do not offer substitutions for those who follow Kosher or Halal diets.

- The current food packages allow appropriate substitutions for celiac disease, gluten intolerance, and lactose intolerance.

Chapter 9

In Chapter 9, the committee reviewed the role of the WIC food packages in reducing nutritional risk factors in WIC participants, the relationship of dietary guidance to program goals, marketplace innovations, and flexibility, choice, and cost within the WIC food packages. The key findings from this review are as follows:

- WIC promotes breastfeeding through “Loving Support,” its social marketing program, and supports it more directly through peer counseling to individual participants and provision of breast pumps.

- Lower proportions of individuals who began participating in WIC earlier in their pregnancies are food insecure compared to those who entered the program later. There is some evidence that self-selection bias may contribute to this finding.

- WIC nutrition education enhances the intended health effects of the food package on participants’ food selection and food preparation.

- Although evidence suggests that a reduction in the energy density of infant formula to 19 kcal per fluid ounce does not inhibit physical growth, the long-term effects of using lower-energy formulas are unknown.

- The 2015 DGAC report did not include a limit for cholesterol intake, which is consistent with recent recommendations from the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology.

- The WIC food packages are currently aligned with the 2015 DGAC report recommendations in that they provide whole grains, low-fat dairy, fruits, vegetables, and protein foods (legumes, peanut butter, fish, and eggs as well as in dairy foods). The allowed foods (other than cheese) are generally low in saturated fat and sodium. The allowed foods (other than yogurt) are low in added sugars.

- The committee’s review of functional ingredients (specifically, docosahexaenoic acid [DHA], arachidonic acid [ARA], probiotics, prebiotics, beta-carotene, lutein, and lycopene) and health outcomes requested by the USDA indicated insufficient scientific evidence supporting health benefits of these ingredients.

Chapter 10

In Chapter 10, the committee analyzed data from FoodAPS on food expenditures by WIC households and calculated the contribution of WIC benefits to total household food expenditures. The WIC households were compared with other households with a pregnant woman and/or child less than 5 years old. The key findings from these analyses are as follows:

- Food insecurity is relatively high among surveyed WIC and other low-income households.

- WIC households spend nearly two-thirds of total food expenditures for food at home.

- Among the nearly one-third (32.3 percent) of WIC households using WIC benefits for purchases during the interview week, the value of acquisitions made using WIC vouchers represented 24 percent of food-at-home expenditures.

PRELIMINARY NUTRIENT AND FOOD GROUP PRIORITIES

The committee’s data gathering and analyses described in Chapters 4 and 5, as well its review of health risks in Chapter 6, led to the identification of potential target nutrients and food groups for WIC participants

of specific ages. These findings are organized in the following tables by age group: (1) nutrients for which inadequacy is apparent in more than 5 percent of the indicated age subgroup, or is prioritized based on other information (see Table 11-1a), (2) nutrients for which mean usual intakes fall below the AI value (see Table 11-1b), (3) nutrients for which more than 5 percent of the population exceeds the UL (see Table 11-2), and (4) food groups for which at least 50 percent of the population falls below or above recommendations (see Table 11-3).

CRITERIA FOR REVIEW OF THE WIC FOOD PACKAGES

The criteria that the committee established to underpin the phase II analyses and evaluation and to guide development of its recommendations are described below and incorporated into Figure 11-1. The final criteria were only slightly modified from the criteria applied by the IOM (2006) Committee to Review WIC Food Packages because, after a thorough review of the evidence, the committee concluded that these criteria were comprehensive and remained relevant. These criteria reflect the committee’s priorities to, first, meet the goals of the WIC program; second, respond to the requirement that the WIC food packages be aligned with the 2015 DGA; and, third, provide a package that is acceptable to participants and feasible to implement at every level. The chapters of the report that contain information relevant to criteria are shown in parentheses.

Criterion 1

The packages contribute to reduction of the prevalence of inadequate nutrient intakes and of excessive nutrient intakes. Rationale: WIC is a supplemental food program and is designed to provide specific nutrients determined by nutritional research to be lacking in the diets of the WIC population. As described in Chapter 4 and listed in Tables 11-1a and 11-1b, the committee’s evaluation of nutrient intakes among WIC-eligible populations led to the identification not only of shortfall nutrients for most subpopulations, but also nutrients with excessive intake for most subpopulations (see Chapters 4 and 6).

Criterion 2

The packages contribute to an overall dietary pattern that is consistent with the DGA for individuals 2 years of age and older. Rationale: At the request of USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS), a goal of the phase II recommendations is to ensure that WIC food packages are consistent with the 2015 DGA. As described in Chapter 5, analyses of available data sug-

TABLE 11-1a Nutrients with Evidence of Inadequate Intakea in the Diets of WIC Participant Subgroups

| Nutrient | Pregnant, BF, or PP Women, 19 to 50 Years | FF Infants 6 to Less Than 12 Months | Breastfed Infants 6 to Less Than 12 Months | Children 1 to Less Than 2 Years | Children 2 to Less Than 5 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | |||||

| Copper | |||||

| Iron | |||||

| Magnesium | |||||

| Zinc | |||||

| Vitamin A | |||||

| Vitamin Dc | |||||

| Vitamin E | |||||

| Vitamin C | |||||

| Thiamin | |||||

| Riboflavin | |||||

| Niacin | |||||

| Vitamin B6 | |||||

| Folate | |||||

| Protein | |||||

NOTES: BF = breastfeeding; FF = formula fed; PP = postpartum. Table is based on results for WIC-participating individuals in NHANES 2005–2008. The committee found no evidence of inadequate intake in the diets of formula-fed infants 0 to 6 months of age.

a Nutrients listed represent those for which 5 percent or more of each population subgroup had intakes below the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR), unless otherwise noted.

b Based on the committee’s literature review findings of a high risk of low iron intakes in breastfeeding infants.

c Based on serum 25(OH)D below 40 nmol/L. Serum levels were not available for infants.

d More than 5 percent of this subgroup had intakes below the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR).

SOURCES: Intake data were obtained from NHANES 2005–2008 (USDA/ARS, 2005–2008). EARs from Dietary Reference Intake reports (IOM, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2001, 2002/2005, 2011a).

TABLE 11-1b Nutrients for Which Mean Usual Intake Falls Below the Adequate Intake (AI) in the Diets of WIC Participant Subgroups*

| Nutrient | P, BF, or PP Women, 19 to 50 Years | FF Infants 0 to 6 Months | Children 1 to Less Than 2 Years | Children 2 to Less Than 5 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium | ||||

| Choline | ||||

| Fiber | ||||

NOTES: BF = breastfeeding; FF = formula fed; P = pregnant; PP = postpartum. Table is based on results for WIC-participating individuals in NHANES 2005–2008. Mean intakes of infants 6 to less than 12 months of age fell above the AI.

* Breastmilk intakes were not quantified for breastfed infants.

SOURCES: Intake data were obtained from NHANES 2005–2008 (USDA/ARS, 2005–2008). AIs from Dietary Reference Intake reports (IOM, 1998, 2005).

TABLE 11-2 Micronutrients with Evidence of Intakes Exceeding the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL)* in the Diets of WIC Participant Subgroups

| Nutrient | P, BF, or PP Women, 19 to 50 Years | FF Infants 6 to Less Than 12 Months | Children 1 to Less Than 2 Years | Children 2 to Less Than 5 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | ||||

| Iron | ||||

| Selenium | ||||

| Sodium | ||||

NOTES: BF = breastfeeding; FF = formula fed; P = pregnant; PP = postpartum. Table is based on results for WIC-participating individuals in NHANES 2005–2008. Only nutrients with intakes above recommended levels in more than 5 percent of the population for at least one population subgroup are presented. The committee’s literature review found no evidence of excess nutrient intake for breastfeeding infants or formula-fed infants 0 to 6 months of age.

* Nutrients represent those for which 5 percent or more of the population subgroup exceeded the UL.

SOURCES: Intake data are from NHANES 2005–2008 (USDA/ARS, 2005–2008). ULs from Dietary Reference Intake reports (IOM, 1998, 2001, 2005, 2011a).

TABLE 11-3 Food Groups with Evidence of Intakes Below and Above Amounts Recommended in the 2015 DGAC Report in the Diets of WIC Participant Subgroups

| Food Group | P, BF, or PP Women, 19 to 50 Yearsa | Children 2 to Less Than 5 Yearsb |

|---|---|---|

| Intakes Below Recommended Amounts | ||

| Total fruit | ||

| Total vegetables | ||

|

Dark green |

||

|

Red and orange |

||

|

Beans and peas |

||

| Total starchy | ||

| Other vegetables | ||

| Total grains | ||

|

Whole grains |

||

| Total protein foods | ||

|

Seafood |

||

|

Nuts, seeds, and soy |

||

|

Total dairy |

||

| Oils | ||

| Intakes Above Recommended Amountsd | ||

| Solid fat | ||

| Added sugars | ||

NOTES: BF = breastfeeding; 2015 DGAC = Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee; P = pregnant; PP = postpartum. Food groups and subgroups listed are those for which 50 percent or more of the population subgroup had intakes falling below levels recommended in the 2015 DGAC report, or in the case of food groups to limit, above levels recommended in the 2015 DGAC report. The table is based on results for WIC-participating women and children in NHANES 2005–2008. The USDA food patterns do not apply to infants and children less than 2 years of age; thus, these age groups were omitted from the table. The committee’s literature review found no evidence to support that specific food group

intakes are low among breastfeeding infants, although low intake of iron-containing foods may be of concern.

a Based on the 2015 DGAC food pattern for a 2,200 kcal diet, which was the EER calculated for women in this report.

b Recommended intakes were generated by weighting the 1,000 and 1,300 (averaged from 1,200 and 1,400 kcal patterns) kcal food patterns in a 1:3 ratio. This results in a food pattern equivalent to approximately 1,225 kcal, slightly under the EER calculated for children 2 to 5 years of age of approximately 1,300 kcal; therefore, intakes for this age group in comparison to recommendations may be slightly overestimated.

c Too few individuals in NHANES 2005–2008 for this age group reported consumption to produce population-level estimates of intake, suggesting that intakes may be low.

d Indicates usual mean intake levels above the upper limit defined by the 2015 DGAC report food pattern comparisons for each age group.

SOURCES: Intake data are from NHANES 2005–2008 (USDA/ARS, 2005–2008). Reference values are the USDA food patterns from the Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (USDA/HHS, 2015).

gest that intake of nearly all of the food groups and subgroups are low in comparison to the 2015 DGAC report food patterns (see Chapter 5).

Criterion 3

The packages contribute to an overall diet that is consistent with established dietary recommendations for infants and children less than 2 years of age, including encouragement of and support for breastfeeding. Rationale: Because the DGA do not apply to infants and children less than 2 years of age, WIC food packages should be consistent with guidance from the AAP, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and the World Health Organization for subgroups within that age group (see Chapters 3 and 9).

Criterion 4

The foods in the packages are available in forms and amounts suitable for low-income persons who may have limited transportation options, storage, and cooking facilities. Rationale: The goal of the WIC food packages to provide food and nutrients lacking in the diets of women, infants, and children cannot be met if transportation, storage, or food preparation barriers prevent redemption or consumption of the issued foods. Considering the degree to which these barriers are present and the means by which the food packages can accommodate the lifestyle of WIC participants is important to attaining the goal of consumption of the issued foods (to be evaluated in phase II).

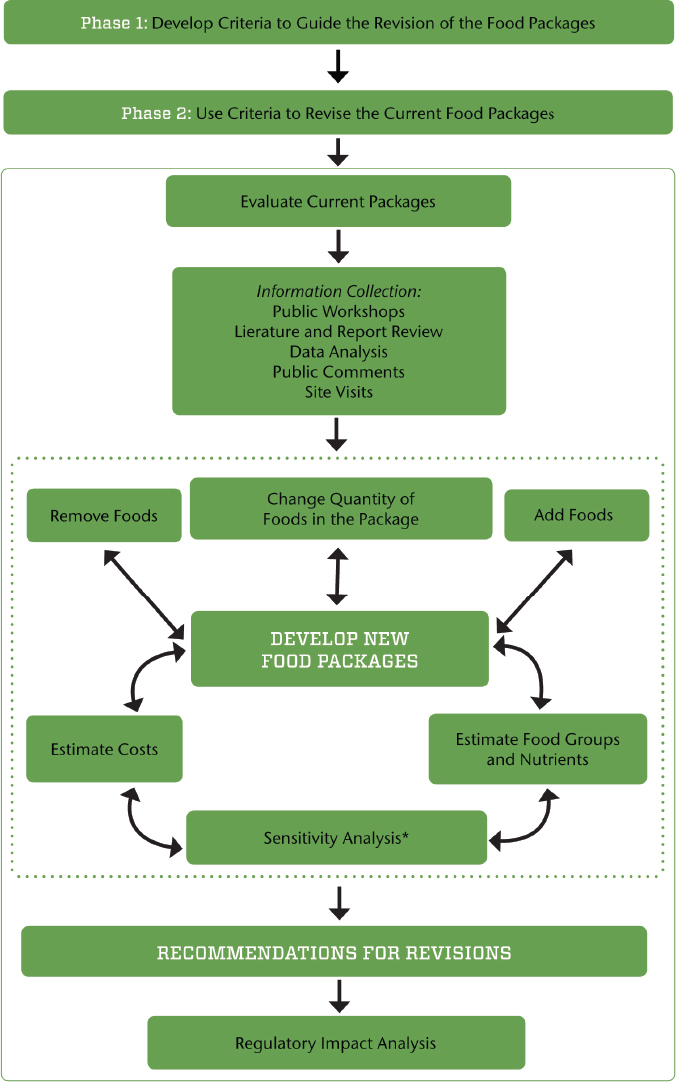

NOTE: The dotted line indicates components of the process that iterate until the criteria for food package revisions are met (see Box S-1).

* The sensitivity analysis includes considerations for maintaining the cost neutrality of the overall WIC food packages.

Criterion 5

The foods in the packages are readily acceptable, commonly consumed, and widely available; take into account cultural food preferences; and provide incentives for families to participate in the WIC program. Rationale: Similar to criterion 4, consumption of WIC foods may be influenced by the acceptability, preferences for, or availability of foods that are issued in the food packages (see Chapters 2, 7, 8, 9, and 10).

Criterion 6

The foods in the packages will take into consideration the effect of changes in the packages on vendors and WIC agencies. Rationale: The WIC program is administered by the USDA-FNS and numerous state and local agencies. At the request of the USDA-FNS, the proposed changes should not unduly add to the administrative burden of these agencies. Additionally, given the central role of the retail food environment on the WIC participant experience (see Figure 2-1), the proposed changes should not unduly add to the administrative burden of WIC vendors (see Chapters 2 and 9).

NEXT STEPS: PROCESS FOR PHASE II

The criteria outlined above will be further explored (and possibly revised) in phase II after consideration of the results of analysis of nutrient and food consumption by WIC participants in NHANES 2011–2012 and limitations related to cost. The committee’s proposed process for revising the WIC food packages in phase II is illustrated in Figure 11-1. The objective is to ensure that the revisions fall within the criteria outlined in the previous section. First, the current food packages will be evaluated for the nutrients and food groups provided as well as the challenges faced during implementation. After reviewing this information, the committee will identify priority changes in the food packages and test possible changes in an iterative fashion to align with the criteria and ensure overall program cost neutrality. The committee anticipates that this process will involve trade-offs, with final recommendations guided by the criteria and cost constraints. Once the iterations result in changes that meet the criteria, recommendations will be finalized. A regulatory impact analysis will then be conducted to assess the effect of changes in WIC food packages on program participation, the value of the food packages as selected, and program costs and administration.

CONCLUSIONS AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE APPROACH IN PHASE II

The overall conclusions based on the committee’s phase I review are summarized below. The conclusions and supporting evidence will be updated and used in conjunction with additional planned analyses to develop the committee’s recommendations in phase II.

- Participation in WIC has declined recently. The reasons for this are likely multifaceted and cannot be attributed to the initial rollout of the food package changes. Paper vouchers are being replaced by EBT, which may improve program participation as well as redemption of issued benefits.

- There are some racial and ethnic differences in satisfaction with specific items in the food packages but, aside from the limited availability of Kosher and Halal food options, the packages appear to be broadly culturally suitable.

- Both women and children (children ages 2 to less than 5 years) WIC participants had low or inadequate intakes of several nutrients that could potentially be addressed with food package changes. These inadequacies may be linked to food intakes that fell below recommendations for specific food groups.

- Women, infants, and children had excessive intakes of several nutrients. In some cases, these excessive intakes may be addressed with changes to the food packages; in other cases, they may be addressed with nutrition education.

- Inasmuch as the sample size of low-income women in the NHANES 2011–2012 analysis was small, it was not possible to estimate the proportion of the population with food group intakes that were inadequate or excessive compared to recommended intakes. Small sample sizes for some of the population subgroups are likely to limit further disaggregation into WIC participants and WIC-eligible nonparticipating individuals. Therefore, in phase II, mean intakes can be compared between groups and to recommendations, but a population-level comparison to recommended intakes for women before and after the 2009 food package changes is unlikely to be possible.

- The committee notes that the NHANES 2005–2008 nutrient and food intake data do not capture the impact of the 2009 food package changes. Results from these survey years are therefore not suitable to serve as the sole basis for final determination of nutrient and food group priorities in phase I. The nutrient and food group gaps identified in this report will be re-evaluated in phase II as the

-

NHANES 2011–2012 “WIC” identifier is incorporated into the analysis.

- Breastfeeding promotion and support appear to play a role in the improvement of breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity among WIC participants. The 2009 changes to the food package to improve support for breastfeeding women were associated with only limited positive changes in breastfeeding behavior. There may be additional possibilities for aligning the food packages with support for breastfeeding women.

- The current WIC food packages provide adequate options for participants with most major food allergies, celiac disease, and food intolerances, but inclusion of substitutions for eggs and fish may be warranted.

- Vendors and manufacturers were able to adapt to the 2009 food package changes with some challenges. It is important to consider the feasibility of potential future food package changes from the perspectives of vendors and food manufacturers.

The committee’s phase II activities will include an update to the comprehensive scientific literature review that was conducted for this interim report, a re-evaluation of the nutrient and food intake data compared to the 2015 DGA, an evaluation of nationwide costs and distribution of foods to ensure that the recommended new food packages are efficient for nationwide distribution, and sensitivity and regulatory impact analyses. A sensitivity analysis will consider each recommended alternative food item and change in quantity relevant to nutrients, the DRIs, food groups and subgroups, and cost. A regulatory impact analysis will assess the impact of proposed WIC food package changes on program participation, the value of the food packages, and program cost and administration. Additional details of the approaches to be used for the different activities are discussed in Chapter 3. Additionally, the committee will continue its iterative process and modify the criteria described above and the decision-making framework for making changes to the food packages, if deemed necessary.

REFERENCES

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1997. Dietary reference intakes for calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D, and fluoride. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 1998. Dietary reference intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, and choline. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2000. Dietary reference intakes for vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2001. Dietary reference intakes for vitamin A, vitamin K, arsenic, boron, chromium, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, silicon, vanadium, and zinc. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2002/2005. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2005. Dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011a. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011b. Child and adult care food program. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

USDA/ARS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Agricultural Research Service). 2005–2008. What we eat in America, NHANES 2005–2008. Beltsville, MD: USDA/ARS (accessed December 15, 2014).

USDA/ARS. 2011–2012. What we eat in America, NHANES 2011–2012. Beltsville, MD: USDA/ARS (accessed December 15, 2014).

USDA/FNS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Food and Nutrition Service). 2014. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC): Revisions in the WIC food packages; final rule, 7 C.F.R. § 246.

USDA/HHS (U.S. Department of Agriculture/U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2015. The report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015, to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: USDA/HHS. http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/PDFs/Scientific-Report-of-the-2015-DietaryGuidelines-Advisory-Committee.pdf (accessed May 24, 2015).