3

Interpersonal Communication

The workshop’s first panel session featured three presentations that explored the role of interpersonal communication in determining how patients experience palliative care. Beverly Alves, a patient advocate and retired teacher who was on the steering committee for Single Payer New York and the National Coalition Leadership Conference for Guaranteed Health Care, recounted her experiences with the health care system when her husband was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Thomas Smith, Director of Palliative Care for Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Hopkins’ Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, then spoke about the challenges physicians face in communicating prognosis to patients. Justin Sanders, Research Fellow with the Serious Illness Care Program at Ariadne Labs, Instructor in Medicine at Harvard Medical School, and an attending physician in the Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care department at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, concluded the presentations by describing how health literacy hits into a scalable intervention to improve serious illness care. An open discussion moderated by Diane Meier followed the three talks.

PERSPECTIVES OF A PATIENT’S WIFE1

On October 4, 2006, Beverly and Joe Alves received a phone call that changed their lives forever. To that point, Joe was physically healthy but had

__________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Beverly Alves, patient advocate and retired teacher, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

developed a backache after moving a large part of a tree that had fallen in the road. When his back was still hurting 6 weeks later, Beverly finally convinced Joe to see his doctor, who agreed with Joe that he had pulled a muscle and to give his back some more time to heal. Some weeks later, a doctor friend of theirs encouraged Joe to see a gastroenterologist given that he was also experiencing some mild symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The gastroenterologist also suspected Joe had a pulled muscle, but to be sure, he ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan, which revealed a mass on Joe’s pancreas and led to that fateful October phone call and what became a less-than-optimal experience with the health care system.

“From the moment we learned of the mass to the day Joe passed on, we were confronted and confounded by a medical system that was uncoordinated and unable to deal effectively with what became Joe’s excruciating pain, our anxiety, stress, and impending loss,” said Alves. “I don’t believe any one of those things caused Joe’s passing, but if there had been a comprehensive plan in place with specified criteria, which would have indicated if and when Joe needed services, it would have done a lot to help us deal more effectively with the overwhelming crisis of Joe’s illness and his impending death.”

The problems she and Joe encountered began almost immediately. To start, the gastroenterologist’s office failed to schedule Joe’s biopsy in a timely manner, and it took repeated calls from Beverly to schedule the pancreas and liver biopsies. By then, Joe was in substantial pain, and they were both anxious to learn what was wrong with him. While waiting for the biopsies, Beverly began searching for an oncologist. The first one, recommended by an acquaintance, had such a dehumanizing manner that they left his office feeling as if Joe was already dead. “He silently read the reports of Joe’s magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and CT, making faces of horror,” she recounted. After giving her husband a cursory exam, he turned to her, looking into her eyes, and he said there was no hope. “No hope, while Joe was sitting just a few feet away, and no matter what I said or asked, this doctor had something negative to say in reply,” said Alves. “Without hope, there is no life.”

All of this time, Joe was in pain—what was in fact a tumor pressing on a nerve in his back—and his family physician was writing emergency prescriptions for pain medications that had to be refilled every 48 hours. Alves recalled watching her husband counting pills to see if he would have enough to last 48 hours knowing he needed a higher dose to control his pain. Making matters worse, Joe and Beverly lived in the country, and getting to the pharmacy in town in winter was often difficult. “It was a true nightmare,” said Alves.

Joe finally had a biopsy, except the surgeon did not biopsy Joe’s liver for some reason. When Beverly tried to query the surgeon, she was inter-

cepted by a nurse. “No one seemed to understand or care,” she said. The gastroenterologist called a few days later, informed Joe that the results of the biopsy were not good, and then hung up before providing a referral to an oncologist or a prescription for his intense pain. “We were left on our own to get Joe the care he needed.”

By then, Beverly had been networking and through a friend got the name of a surgeon at Albany Medical Center, but when she called to make an appointment she was told that while the surgeon was available, the scheduler was out. After 3 days of repeated calls trying to schedule an appointment, Beverly began to sob, which finally moved someone to schedule an appointment with the surgeon 2 days later. However, with no liver biopsy, the surgeon said he could not determine what course of action to take, and referred Joe for a liver biopsy, which revealed that the cancer had spread to his liver. The surgeon arranged for Joe to meet with an oncologist.

As soon as Joe learned he had inoperable metastatic pancreatic cancer, he volunteered to do clinical trials. “He wanted to do this not only to help himself, but to help make things better for mankind, and the oncologist said he would fight this with us together,” said Alves. “We left the hospital that day with our heads held high with hope in our hearts. The next week was Thanksgiving, and we had one of the nicest Thanksgivings we had ever had because we had some hope.”

Unfortunately, during Thanksgiving weekend, Joe’s cancer produced thrombotic clots, which caused him to have a stroke. There were no neurologists in the rural county where they lived, so the Alves waited in the emergency department while the attending physician fruitlessly searched for neurologists in other areas and Joe became paralyzed. Finally, around 5 a.m., Joe was rushed to Albany Medical Center. “The people who worked at Albany Med were caring and dedicated, but there was no system to coordinate care there,” recalled Alves. “The analogy I use is it should have been a ballet, but instead there were many great ballroom dancers.” Albany Medical Center, she added, did not have a palliative care program then and still does not nearly 9 years later.

She remembers Joe being a wonderful patient who did his best to help those who were helping him. He was stoic despite being in monumental pain. One night, she recalled, his pain was so intense that he repeatedly asked for more pain medication. “Joe’s pain became so intense he started to weep. My heart broke and I wept along with him. When the nurse came into his room and saw us both weeping, she worriedly asked what is going on. Joe said we are sharing sorrow,” recounted Alves. The nurse, nearly brought to tears herself, told them she had made repeated requests to the pharmacy through both voicemail and e-mail, but there was nobody to speak to directly in the pharmacy, even in the case of emergency. While Joe did eventually get additional pain medication, Alves witnessed a similar

scene the next night in which a young woman, who she characterized as little more than a girl, was standing at the nurse’s station, weeping and pleading for pain medication. “This is unacceptable,” said Alves. “It is inhumane.”

Along with intense pain, Joe was highly anxious, yet he was never referred to a pain management specialist or given adequate medication for his anxiety. Alves noted that shortly after her husband died, a psychiatrist told her that a living will should request medications to reduce pain and anxiety because the dying process can itself produce anxiety.

One week before Joe passed, he looked very ill, and Beverly asked the oncologist liaison if her husband needed hospice. The answer was no because nobody had said he had 6 months or less to live. The same night, a hospitalist, who she said was a very caring doctor, told her he did not think Joe would make it through the night. “I was aghast,” said Alves. “Nothing major had happened during the day. It was just different interpretations of Joe’s conditions made by different people because there was no coordination of care.” The hospitalist, she said, had Joe moved to a single room and staff asked her for directions regarding end-of-life decisions because they could not find the living will Joe had brought with him to the hospital.

“Watching your loved one die is a terrifying and agonizing experience,” she said. “It is one thing to be sitting safely in your attorney’s office making out a living will and another to confront the impending loss of your beloved. I knew Joe had signed a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order, but at that point, I was nearly stuporous.” She asked to speak with the hospital’s ethicist and while he gave her good advice, he did it over the phone. “When a patient is dying, family members are in crisis too and also need support, but I was alone,” Alves recalled.

The ethicist told her to ask her husband what he wanted done if something happened during the night, but he was in great pain and exhausted and did not want to discuss anything. When she asked him specifically if he wanted to be on a ventilator, he did say no, and she gave that information to staff. Nobody bothered to enter it into his medical record, however, resulting in further confusion and anguish later that night when a resident came in to talk to them about ventilation and resuscitation. Joe never got back to sleep that night, and early that morning he told his wife that the odds were not in his favor and that he was facing death. Alves was beside herself, but then she remembered something that Rabbi Pesach Krauss had written in his book, Why Me? (Krauss and Goldfischer, 1988). Krauss, who was a chaplain at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, wrote that when he spoke with patients who were very ill and fearful, he would ask them what they wanted to do with the time they had left. Beverly asked Joe that question, and he said he wanted to enjoy himself at home. Beverly told this to Joe’s oncologist, but that doctor, the same one who told them less

than 1 month before that we would be a partner with them, told her to put Joe in a nursing home. “I can still remember and probably always will my knees starting to buckle under me when he told me this,” said Alves. “I felt like he was just tossing Joe away.”

At that point, her plan was to place Joe in a new hospice facility in her county for a few days until she could connect with a home health care planner. The day before his planned move, a hospice nurse visited him, saw how badly he was suffering, and concluded that the staff at Albany Medical Center had no idea on how to ease Joe’s pain. She asked staff to start him on the pain medication he would receive at hospice, and his pain finally subsided and he was able to relax.

Alves recalled that when she and Joe first started on this journey together he had said he would do everything he could do to get better. He asked her only one question. “He asked me what I would do if he could not go on anymore. I told him I would let him go, and when the time came, with much pain and deep sorrow, I did,” she said. The next morning, December 18, while she was in the bathroom in Joe’s room, he passed away quietly.

In recounting some of the many incidents that caused her husband to endure needless pain and anguish, Alves said she hoped she was conveying the message of how palliative care would have gone a long way to helping ease his suffering and her grief at seeing it. “Fortunately, before Joe passed, we were able to tell each other we knew we were the right partners for each other. Joe told me I was the queen of his heart. He was the king of mine,” said Alves. “I feel blessed that we were able to hold on to each other and cherish the time we had left in spite of his terrible illness and the problems we encountered, but it could have gone the other way because of things that did and did not happen during Joe’s illness.” She added that the last few days of a person’s life are important. “As badly as I still feel about Joe’s passing, I would feel much worse if things had not been good between us when he passed.”

After Joe died, Beverly asked friends if they would want to be told if they had a serious or life-threatening illness. “Our friend, George, said it best. He said he would want to be told. ‘You are very sick, but we are going to do everything we can to help you,’” recalled Alves. She added that while many medical professionals are bright and filled with essential medical knowledge, they need to learn to speak to a patient and the patient’s family and loved ones with compassion. “Patients are human beings with hopes, dreams, fears, and sorrows,” said Alves. “They are not simply an accumulation of cells, organs, and systems. To treat only a disease or an injury is to be merely a body mechanic.”

She then offered some advice to the health care professionals at the workshop. “When speaking with a patient, especially one who is critically

ill, pause, take a breath, think, listen, or pray,” said Alves. “Treat patients and their family members the way you would want to be treated, the way you would want your family members to be treated. Be a partner with your patient in their healing. Studies show that people heal better when they have a support system, so be part of that support system because even if you cannot cure your patient, it will make all the difference in the time they have left. Then you will truly be healers.”

COMMUNICATING PROGNOSIS2

Thomas Smith began his presentation by offering Alves an apology for what she endured on behalf of all medical oncologists everywhere, and offered hope that the next generation of oncologists would do better. He acknowledged that he and his colleagues are not doing a good job about communicating prognosis, but he also offered the possibility that there are ways to do better, including listening to and learning from stories such as the one Alves had just told.

He then provided two definitions as context for his talk. Literacy, he said, is the ability to read and write, and readability can be measured using indices such as the Simplified Measure of Gobbledygook (SMOG) or the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) (Dumenci et al., 2013). Most hospice brochures, he said, would score at a sixth grade or higher level using these types of measures. Literacy, added Smith, is different from health literacy, which is the degree to which an individual has a capacity to obtain, communicate, process, and understand basic health information and services to make appropriate health decisions. According to 2003 statistics, some 98 million incidents of poor outcomes, additional hospitalizations, lower compliance, higher mortality, and reduced use of hospice resulted from health illiteracy. Factors contributing to health illiteracy include race, age, education level, poor vision, and comorbidities (Matsuyama et al., 2011). Given that medical care is more complex than in 2003, Smith said that this number is likely to be higher today, though he and his colleague Robin Matsuyama have been unable to find updated statistics.

The benefits of health literate palliative care are plentiful, said Smith. Ten randomized clinical trials of palliative care added to usual care, versus usual care alone, among patients with a variety of serious illnesses, for example, found no harm in any trial. There was a compelling increase in better satisfaction and communication with providers, less depression

__________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Thomas Smith, Director of Palliative Care for Johns Hopkins Medicine and the Hopkins’ Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the Academies.

and anxiety with more prognostic awareness, and an increase in hospice referrals (Parikh et al., 2013). In most cases, quality of life and symptom control were better and costs were lower by at least $300 per day. Four of the then trials showed that even with increased prognostic awareness, patients lived longer.

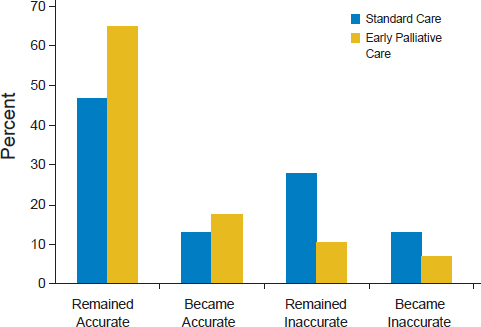

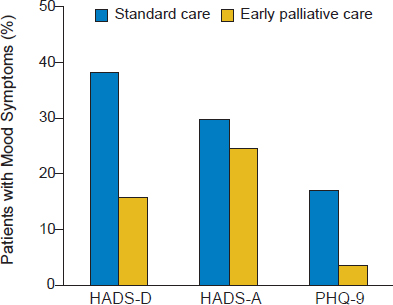

A 2010 study (Temel et al., 2010) in particular got everybody’s attention, Smith noted. This trial randomized usual care versus usual care plus one palliative care visit per month for 151 newly diagnosed non-small-cell lung cancer patients. This study found that the patients assigned to early palliative care not only had a better quality of life than did patients who only received standard care, but they survived almost 3 months longer (Greer et al., 2012) with less aggressive care at the end of life (Roeland et al., 2013). Though prognostic awareness increased in patients receiving palliative care (see Figure 3-1), those patients experienced less depression and anxiety and had better mood (see Figure 3-2). Early palliative care also increased documented resuscitation preference, increased the number of patients who received hospice care 7 days or longer before death, and nearly tripled the number of days spent in hospice (Greer et al., 2012). “Show me another branch of medicine that improves quality of care,

SOURCE: Temel et al., 2011.

NOTE: HADS-A = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety; HADS-D = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Depression; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire.

SOURCE: Temel et al., 2010.

improves the quality of lived experience for people, and lowers cost,” said Smith.

To explain the success of palliative care, he and colleague Betty Ferrell from the City of Hope developed the acronym TAME—time, assessment, management, and education. The time required, he explained, is about 1 hour per month. There have to be formal assessments for symptoms, spirituality, and psychosocial factors. There needs to be management protocols in place and educational tools to help patients and families learn about prognosis, coping skills, advanced directives, hospice, and legacy. Though not complicated, said Smith, these have to be scripted to get the best results.

Smith said he was not surprised that palliative care increased time of survival given a study he conducted showing that better pain management increased survival time in cancer patients by more than 3 months (Smith et al., 2002, 2005). More recent studies have found similar results with regard to increased survival times associated with palliative care for cancer patients (Bakitas et al., 2015), and a study involving patients with dyspnea who received integrated palliative care and respiratory care compared to the usual respiratory care found that palliative care reduced the chances

of dying at 6 months by 30 percent (Higginson et al., 2014). “If this was a drug, we would be at the FDA [U.S. Food and Drug Administration] demanding its approval,” said Smith.

Despite results such as these, communication today between doctor and patient is not satisfactory, said Smith. One study found, for example, that only 17 percent of lung cancer patients could guess that their prognosis with stage IV disease was less than 2 years (Liu et al., 2014), while another study found that 69 percent of patients with stage IV lung cancer and 81 percent of stage IV colon cancer did not understand that chemotherapy was unlikely to cure their cancer (Weeks et al., 2012). Whether a patient responded accurately to questions about the likelihood of chemotherapy curing their cancer was not associated with race or ethnic group, education, functional state, or a patient’s role, but it was associated with being in an integrated care network and with lower scores for physician communication. “If your physician was blunter with you, you understood better,” said Smith. These observations, he added, contrast sharply with data showing that 80 percent of patients want to know the full truth about their diagnosis even though it may be uncomfortable or unpleasant (IOM, 2013). He noted, too, that oncologists such as himself almost always tell their patients that their disease is incurable, but then in collusion with their patients, they quickly transition the discussion to one of treatment options and schedules, leading to false optimism. The subject of prognosis never comes up again for most patients, he said.

The same data set showed that the chances of having inaccurate prognostic awareness increased in Latinos, African Americans, and Asian Americans. Smith said he did not know if this disparity resulted from who the patients were, who was or was not presenting the information, what the patients are hearing, how they are being told, or some combination of these factors. Another study, with similar results, found that patients overestimated the likelihood of cure after surgical resection of lung and colorectal cancer (Kim et al., 2015). Women and unmarried individuals were slightly less likely to have inaccurate prognostic awareness, but African Americans and Asian Americans were more likely to believe surgery would be curative.

Smith briefly discussed a study showing that video presentations about end-of-life decisions are more effective than just talking to patients at influencing the patient’s perceptions and decisions (Volandes et al., 2008). This finding was consistent regardless of race and literacy level, and regardless of educational level. He noted that African American physicians were far more likely than their Caucasian colleagues to want to be resuscitated, be on a ventilator, or have artificial feeding, while Caucasian physicians were more likely to want physician-assisted suicide (Mebane et al., 1999). However, when asked if tube feeing in terminally ill patients is heroic, 28 per-

cent of African American physicians replied yes compared to 58 percent of Caucasian physicians.

Smith noted that the Internet is not a good source of information on prognosis either (Chik and Smith, 2015). He and a colleague checked the American Cancer Society’s website, the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Cancer.gov, uptodate.com, and at least one disease-specific website looking for information about prognosis for stage IV cancer. Only 26 out of 50 websites had some notation of 5-year survival, and only four websites gave any information about what the average person could expect in terms of median survival. Only 13 websites noted that stage IV cancer was a serious and usually life-ending illness. On a positive note, nearly all had some information about hospice and palliative care, though none gave specific recommendations.

Most hospice and palliative care information, even from nationally prominent palliative care organizations, is written above the recommended sixth grade level and is not readable (Ache and Wallace, 2009; Brown et al., 1993), said Smith. About one-third of these materials require university-level literacy skills for full patient comprehension. “End-of-life patient education materials should be revised for average adult comprehension to help informed decision making and to aid in closing the gap in health literacy,” said Smith. Studies have shown, in fact, that better communication about prognosis changes the process of care. For example, a question prompt list has been shown to increase the number of questions people have about end-of-life and prognostic issues (Clayton et al., 2007), and Smith noted that he and his colleagues are creating a question prompt app. Video decision aids also help patients make better choices about end-of-life care (El-Jawahri et al., 2010; Volandes et al., 2013), and electronic prompts given to physicians have been shown to increase the number of people who express their preferences for life-prolonging interventions and resuscitations (Temel et al., 2013). Teaching patients about standards of care will even change the median time to a DNR order from 12 days to 27 and reduce the hospital death rate from 50 percent to 19 percent (Stein et al., 2013), Smith noted.

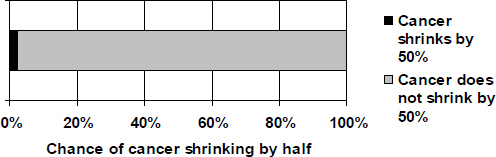

He and his colleagues have created decision aids to help patients make better end-of-life decisions. One such aid was developed for the American Society of Clinical Oncology for use with patients with stage IV lung cancer (Smith et al., 2011). It presents answers in response to common questions such as, “What is my chance of being alive at 1 year?” and “What is the chance of my cancer shrinking by half?” (see Figure 3-3). The decision aid also answers questions such as, “Are there other issues that I should address at this time?” that provides information on resuscitation, family and spiritual issues, financial matters, and hospice. “The interesting thing about this aid is that it does not take away hope,” said Smith, who noted that measurements taken before and after patients used the aid showed that if

SOURCE: Presented by Thomas J. Smith on July 9, 2015.

anything, the level of hope increased slightly (Smith et al., 2010). He added that the California Healthcare Foundation plans to release truthful decision aids for the 10 leading causes of cancer deaths in late 2015.

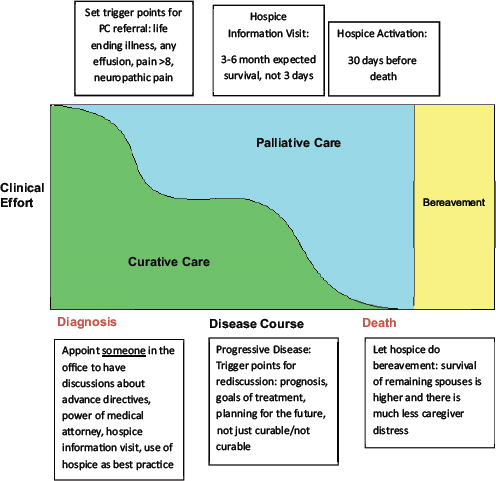

The ultimate goal, said Smith, is to change office practice so patients who could benefit from palliative care are identified at the time of diagnosis rather than at the end of life (see Figure 3-4). “We want physicians to bring up palliative care when the cancer starts to grow, when heart failure starts to get a little worse, when diabetes starts to cause more vascular complications.”

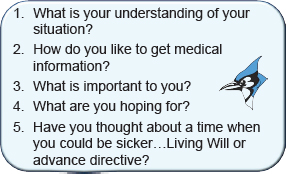

Smith is now working with all of the providers at Johns Hopkins Medicine to provide a research-based palliative care communication tattoo that would go on the forearm of every patient with a serious illness (Morris et al., 2012). The tattoo will list the following questions that patients should be asking themselves and their physicians (see Figure 3-5).

Smith concluded his talk by reiterating that 80 percent of patients want to know and understand their prognosis and that acting on that information makes a big difference in the care they receive and the quality of life they lead. He noted that some patients, for example, turn down second-line lung cancer chemotherapy because they do not think it works when in fact it does improve survival and it does improve quality of life. “Those are good things to know, and if you can understand it, maybe you can choose better,” said Smith, who said he is not about denying people care. What he does want is for more patients to get helpful chemotherapy and fewer patients to get unhelpful chemotherapy, for there to be greater use of hospice, less patient and family distress, longer survival, and for patients to die at the place of their choosing. Smith added there needs to be rewards for doing this tough work, better decision aids for patients, and prompts

NOTE: PC = palliative care.

SOURCE: Wittenberg-Lyles et al., 2015.

SOURCE: Presented by Thomas J. Smith on July 9, 2015.

that remind physicians to have these discussions, such as the smartphone app that he and colleagues are developing with funds from the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship. Physicians, he said, need better communication skills, though in the end, it may be important to have a member of the palliative care service handle this important task. “I don’t think many oncologists are wired this way,” said Smith.

SERIOUS ILLNESS COMMUNICATION PROGRAM3

The topic of palliative care and health literacy is compelling to Justin Sanders not only because of the work he does in this area but because the field continues to grapple with trying to improve comprehension of what palliative care means and who it benefits. He also said that he agrees with the sentiment that this is a health literacy issue that is as acute for physicians and other members of the health care team as it is for patients.

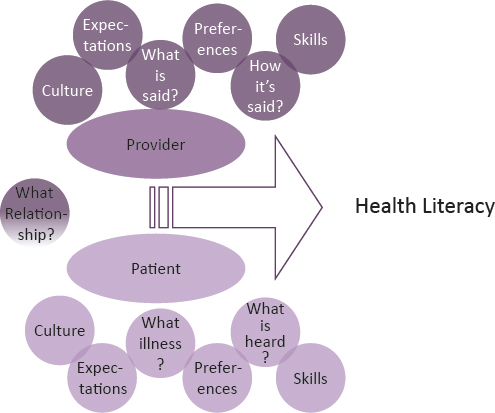

Just as Smith did at the beginning of his presentation, Sanders started with some definitions to set the boundaries for the concepts he would be addressing. He characterized his definition as expansive and is based on the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion (IOM, 2004), which defined health literacy as the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions. That report went on to describe health literacy as an emergent phenomena that occurs when expectations, preferences, and skills of individuals seeking health information meet the expectations, preferences, and skills of those providing information and services. In other words, said Sanders, health literacy is not something individuals possess, but it is something that emerges from the interaction between clinician and patient. Health literacy is also sensitive to the demand it places on a person to decode, interpret, and assimilate health messages, and as a result it is dynamic and situation dependent.

In terms of palliative care, Sanders said he would be referring to a set of services concerned with patients in all phases of serious illness, which is to say an illness that places a person at high risk of incapacity or dying within a certain time frame. He agreed with the previous speakers who said it is a health literacy problem that has physicians continuing to believe that palliative care only has a role at the end of life.

__________________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Justin Sanders, Research Fellow with the Serious Illness Care Program at Ariadne Labs, Instructor in Medicine at Harvard Medical School, and an attending physician in the Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care Department at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. The statements are not endorsed or verified by the Academies.

The Serious Illness Care Program at Ariadne Labs, he then explained, developed a systematic and systems-level approach to address two fundamental gaps in the care of seriously ill patients and their families. The first is the gap between what patients want for care and what they receive in the setting of serious illness. “Most Americans, including those of all colors and creeds, wish to spend their final days at home and want less aggressive and more symptom-focused care, especially when they are aware of a terminal diagnosis,” said Sanders. “They do not want their dying prolonged, they do want a sense of control, and they do not want to burden their family and friends.” What most patients get looks somewhat different, he said. Most Americans die in institutions, and aggressive care with little or no benefit is common. Hospice use is increasing, but the length of stay in hospice has been falling (NHPCO, 2014), and transitions in the last 3 days of life are on the rise (Teno et al., 2013). Among the consequences of this gap, said Sanders, are inadequate symptom control and poor quality of life for patients and their caregivers.

The program also addresses the gap between what is known about how to provide high-quality end-of-life care and what the health care enterprise delivers. More specifically, said Sanders, it is well documented that discussions to clarify goals, values, and priorities for care—advance care planning discussions—improve clinical outcomes as measured by more goal-concordant care, less aggressive care, more and earlier hospice care, and higher patient satisfaction and family well-being (Brinkman-Stoppelenburg et al., 2014) without making patients more anxious, depressed, or lose hope. “Early conversations about goals and priorities enhance a patient’s sense of control, providing space for planning and closure and focusing patients and families on what matters most,” said Sanders.

At the same time, he added, there is a connection between physician burnout, poor self-efficacy, and caring for patients with serious illness (Meier et al., 2001), yet clinicians feel closer to patients and better about the care they provide when they speak earlier and often with the seriously ill patients about their goals and priorities. What happens in most health care settings, however, is that these conversations occur too infrequently or too late in the course of disease progression, particularly in communities that suffer disproportionately from low health literacy. In addition, added Sanders, clinicians are not that good at having these conversations.

The Serious Illness Program addresses these gaps with a process involving the following steps:

- Identify seriously ill patients.

- Train clinicians in the use of a structured conversation guide.

- Prepare patients to participate in these conversations.

- Prompt the clinician to have the discussion.

- Have the discussion.

- Document the discussion in a single, easily locatable place in the electronic medical record (EMR).

- Provide materials to the patient to carry on the conversation with their family members.

The heart of the process, Sanders explained, is the Serious Illness Conversation Guide, which prompts the clinician to ask the patient two questions: (1) What is your understanding of where you are now with your illness? and (2) How much information about what is likely ahead for you would you like from me? At that point, the guide encourages the clinician to share the prognosis and then pose five additional questions:

- If your health situation worsens, what are your most important goals?

- What are your biggest fears and worries about the future with your health?

- What abilities are so critical to your life that you cannot imagine living without them?

- If you become sicker, how much would you be willing to go through for the possibility of gaining more time?

- How much does your family know about your priorities and wishes?

Sanders then discussed the Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST) paradigm that he believes is less likely to open this space in a sustainable manner. POLST and similar paradigms are physician orders for life-sustaining treatment, and all but five states have some version of the POLST form in place. Sanders considers it problematic for several reasons, the first of which is that the POLST paradigm was created without clear thinking about how to train clinicians to have these discussions. “It seems as if the goal is to force the discussion using a tool to clarify procedural options for care, which puts the cart before the horse,” said Sanders. The horse, in this case, would be the goals and priorities that inform people’s ideas about what kind of care they want.

Continuing with this analogy, Sanders said the cart had its own problems, namely that advance directives are a contested strategy for delivering goal-concordant care in that they do not always guarantee that patient wishes are followed (Hickman et al., 2015; Mirarchi et al., 2015). In some cases, a family member may reverse a patient’s wishes, while patients themselves can change their minds in response to serious illness in ways that a POLST form may not reflect, explained Sanders. In addition, the interventions listed on the POLST form are often poorly understood by patients or family members who may not know the effect of the listed treatments,

their risks, and their benefits. “Even if they did know of these treatments, how do we know that the way we are explaining them facilitates the kind of comprehension that leaves people feeling confident in their decisions,” said Sanders. “That is a health literacy issue.”

Thinking about health literacy as an emergent phenomena, one that emerges in a way that affects behaviors of both patient and physician, requires being acutely sensitive to the power dynamics that exist between two parties with different cultural, social, and educational backgrounds and how that dynamic affects the space in which discussions about palliative take place (see Figure 3-6). The biggest power dynamic, said Sanders, is the one between a patient with serious illness and the clinician, insurer, or health system with the capacity to cure or hold at bay the patient’s disease. “We have to think about what it means when this treating clinician either allows the possibility for treatment goals to change or refers to a clinician with that

SOURCE: Presented by Justin Sanders on July 9, 2015.

power,” said Sanders. Factors that widen that gap and that are relevant to health literacy include education, socioeconomic position, and race.

Assuming that power differentials are evident in the process of advance care planning, one strategy for creating safe space is to give control to the patient. The approach that Sanders and his colleagues use is to prepare patients to have this discussion by asking their permission to have it and then assessing and honoring their information preferences. They do this by asking questions in ways that allow the patient’s humanity, not the illness, to come through in a manner that actively shapes the care. “A conversation focused on the POLST form does none of that intentionally and risks exacerbating the inherent tension in the relationship by focusing on life-sustaining procedures and not to the issues of survival, suffering, quality of life, and meaning that are most important to patients and families,” said Sanders. “In the POLST paradigm, we are forcing the patient and family onto our turf, into the medical model, and failing to honor the patient’s experience and perspective.”

The problem of obtaining goal-concordant care is particularly acute for African Americans, said Sanders, in part because of structural and interpersonal factors but also from the fact that African Americans compared to Caucasians engage in advance care planning less often (Daaleman et al., 2008). The latter stems from multiple factors that include mistrust in both clinicians and the health care system, decision making informed by religious principles, family decision-making styles, and health literacy (Nath et al., 2008). Sanders said that it is hard to know the full impact of health literacy on advance care planning (Melhado and Bushy, 2011), in part because health literacy as measured in studies that have examined its role in advance care planning is somewhat unidimensional, typically by using measures such as grade reading level. “But if we think of health literacy as emerging from both the patients’ experiences and their interaction with clinicians, then health literacy might be the central issue relating to achieving goal-concordant care,” said Sanders.

The key challenge he and his colleagues face is to think about how an intervention developed in a place that serves a predominantly white, middle- and upper-middle-class-population can affect other important U.S. populations, especially African Americans. “How do we move it out of a temple of science and into a temple of worship,” said Sanders. Their approach, he explained, has been to conduct a series of focus groups aimed at identifying high-risk barriers to participation in conversations such as these, gaining feedback about the language and content of the Ariadne Labs Serious Illness Conversation Guide, and then modifying the guide so it can be implemented in a culturally sensitive manner. He emphasized that they are not creating a guide specifically for African Americans, but rather they are thinking about how to give guidance to clinicians about

language and issues that will enable them to better create the safe place for discussing end-of-life issues. “If these modifications are useful to African Americans, they may be useful to others as well,” said Sanders, who added that the process of identifying these modifications is one they can repeat with other populations.

He and colleagues have learned a number of important lessons through this process. For the most part, he said, the space in which goals of care are discussed with African Americans with serious illness is in the hospital during a crisis. These interactions are emotionally traumatic for families and add to a collective historical trauma felt acutely by members of the African American community, heightening senses of stigma and mistrust. In addition, the relationship between the patient and family and members of the clinical team, and in particular the physician, is paramount to the sense of safety for patients and families in approaching the end of life. As far as the guide itself, the questions have been easily understood and acceptable to the African American participants in the focus group. Moreover, the questions enhanced the participants’ sense of feeling cared for, while the addition of the question “What gives you strength and comfort as you think about the future with your illness?” effectively elicits and allows for religious faith to enter the conversation in a way that enhances this sense of caring.

In conclusion, Sanders said that it is more useful to think of health literacy as an emergent phenomenon rather than as something that is or is not possessed by an individual. He added that for health literacy to emerge in a way that supports advance care planning and palliative care, the focus needs to move away from advance directives to scalable, translatable communication practices that help patients and clinicians enter a space together without fear of ineptitude on the part of clinicians or abandonment on the part of patients.

DISCUSSION

Diane Meier started the discussion by asking Alves for her reaction to the two presentations. In Alves’s opinion, there needs to be a campaign to educate both the public and medical community about the availability and importance of palliative care, noting that she had essentially been providing palliative care for her husband even though she was a special education teacher. Shortly after Joe passed, she wrote a letter to Albany Medical Center describing what she had been doing for her husband. A friend of hers, who was the head of rehabilitation services at a local facility, read the letter and told Alves that she had been providing palliative care. Alves replied to her friend, “What is that?” She added that she thinks the medical community is moving in the right direction.

Meier then noted how both Smith and Sanders had emphasized the importance of communication about what to expect and the need to give power to patients and family members to guide the actions of the health care team. She repeated Sanders comments about the failure of the turnkey approach to advance care planning and asked Smith and Sanders to speak about the lack of fit between patient and family needs and standard approaches to end-of-life care. Smith said he takes a practical, hands-on approach that starts with knowing what he needs to do if a person’s body starts dying well before that happens. He said that while he appreciates the cart-before-the-horse analogy, he also knows how difficult these questions are for a health care provider such as himself to ask a patient. For example, when he asks patients if they want dialysis, he first has to spend time talking about what dialysis is and what it entails. The same is true for ventilation.

What is important to consider, too, is that the culture of the institution factors into how these questions are asked. He noted that one of his postdoctoral fellows studied how DNR decisions were made at three institutions in the United States and one in the United Kingdom (Dzeng et al., 2015). At the UK hospital, the physician makes the decision and informs the patient, which Smith called the paternalistic model of care. At the University of Washington in Seattle, that decision is a shared one made in partnership with the patient. There, the physicians ask patients about their desires, the quality-of-life issues they find important, and their understanding of their situation. The physicians explain what it means to be on a ventilator and the odds that resuscitation will enable patients to survive. In his experience, the chances of resuscitation being successful is close to zero, and he believes patients have a right to know that to help them make better decisions.

Smith also noted a recent paper showing that the number of people making durable power of attorney assignments increased from 52 percent in 2000 to 74 percent in 2012, but that there was no change in the use of living wills (Narang et al., 2015) despite the fact that the only thing that makes a difference in end-of-life care is having a written living will or written advance directive. “Just having an appointed person makes absolutely no difference,” said Smith, who added that he is tired of hearing his colleagues say that all they need to know is who the decision maker is. That is just a start, said Smith, but it means nothing unless the patient and decision maker have actually discussed what the patient wants. On a practical note, he agreed that the POLST form is often little more than an exercise in checking boxes, but that it does force there to be some discussion about end-of-life decisions. “I don’t think that is a bad idea,” said Smith.

Sanders agreed with Smith about the importance of the patient and appointed decision maker having a real discussion about the patient’s wishes given the work that he and his colleagues have done showing

that end-of-life care is determined more by family members than written advance directives. He then noted that he and his colleagues have seen in their studies that a good discussion between clinicians and patients can be psychologically beneficial and enable patients to go home and have fruitful discussions with their families. “We often hear . . . in talking with the patients about how they walk away from the conversation with their physician and have a better sense about how to talk to their families about end-of-life issues,” said Sanders. He has also found through his experience in training hundreds of clinicians that when they do not ask about procedures, the procedures stop being the focus of conversation, leaving room for the clinicians to better understand their patient’s most important values. That, in turn, allows the clinicians to use their training and make recommendations to patients that fit the patients’ needs and that leave patients feeling cared for in that setting. He added that when health literacy issues are acute and patients are forced to make concrete care decisions to check boxes on a form, they feel lost.

Linda Harris from the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services commented that Sanders’s framing of health literacy as an emergent phenomenon has the potential to be powerful, but it also has the potential of challenging health care providers to take some responsibility for improving the health literacy of their patients. Given that possibility, she asked Sanders if he had any evidence that health literacy is an emergent rather than a personal characteristic. Sanders responded that this notion came from the IOM report and that his experience supports that idea. “People with poor health literacy know everything they need to know about their goals and values,” he said, adding that what they do not know is how to translate that self-knowledge into understanding the details of clinical care given that clinicians can have a difficult time talking about these issues in ways that make sense to their patients. He recounted how a patient he had spoken to the day before the workshop said that the questions in the guide were good because they forced the doctor to speak like a human rather than a doctor and to truly understand what the doctor was saying. “That is why I think that health literacy is an emergent phenomenon, one that emerges from our interactions with patients as humans,” said Sanders. Harris agreed that was a reasonable view and asked Sanders how the conversation guide takes that idea into account. Sanders said that a major component of the conversation guide is a set of nonthreatening questions designed to create the safe space need to have a thoughtful and thorough discussion. Clinicians, for example, are encouraged to tell their patients that no decision has to be made on the basis of a single conversation.

Wilma Alvarado-Little, founder of Alvarado-Little Consulting, noted how Smith had mentioned that some ethnic groups had less prognostic

awareness than others and that Sanders had touched on some issues regarding African American communities. She then asked the panelists if there were any considerations being made for groups of patients and family members whose primary language is not English and for the deaf and hard-of-hearing communities. Before answering the question, Smith recounted a recent call his team received from a patient with liver failure who knew she was very sick and wanted to know how much time she had. The nurse practitioner did a wonderful job talking to the patient about her prognosis and that there was no way to say with certainty how much time she had to live, but after Smith returned to his office he received a frantic call from a staff member who said the family claims the patient does not want to know her prognosis and not to tell her. “What we have learned to do with every culture is to ask patients about their understanding of their situation, and how do they like to get medical information,” said Smith.

He then said that his team has projects in Belize, Saudi Arabia, and Tajikistan, three places with three very different cultures. In Tajikistan, for example, he has seen a surgeon who has just operated on someone with inoperable gastric cancer tell the patient he has an ulcer, to take certain drugs, that he would be okay and then go tell the family that he has weeks to live. Again, he had learned to ask patients about their understanding of their situation and how they want to get their medical information. “Giving people those couple of simple tools is important. Having a script to start these conversations is really key,” said Smith. He also noted that in Baltimore, where he has now worked for 3.5 years, he has been accused of experimenting on people’s loved ones more in that time than in 28 years of practicing in Richmond. “You just have to ask, ‘How do you like to get medical information? What is your understanding of your situation?’” he said. “Never make assumptions about what people want to know.”

Margaret Loveland, a pulmonologist from Merck & Co., Inc., who has treated patients with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diagnosed many lung cancers, commented on the lack of continuity of care that was apparent in the way Joe Alves was treated. She noted that when she diagnosed a patient with lung cancer and referred him or her for radiotherapy of chemotherapy, she always took the time to follow up with and ask the questions Smith gave. She felt that patients will only answer those questions and talk to someone about these issues if they know the person. “With all of these other people coming and going, can you really have a deep conversation with somebody you don’t know?” asked Loveland. Alves said that in her husband’s case, the system did not work at all. “Each doctor that we went to just dropped the ball. There was no coordination of care at Albany Med,” she said. She did commend a physician from the University of Indiana who did try to find an oncologist in upstate New York and who took the time to review her husband’s test results.

Smith then commented that it does not have to be the oncologist or the cardiologist who has these conversations, but it needs to be somebody the patient trusts. “If your primary care physician stays involved, you are twice as likely to get the care you want,” said Smith, citing a study done in Canada (Sisler et al., 2004). He would like to see primary care physicians kept in the loop and receive functional status updates as a mandatory part of care, noting that he can teach anybody in 5 minutes how to write a one-page summary to all care team members in the EMR.

He then told of a study (Dow et al., 2010) in which 75 consecutive patients coming into an inpatient oncology service with an average survival of 3 months were interviewed, and found that only 40 percent of these individuals had advance directives; the percentage was slightly lower in African Americans and slightly higher in Caucasian. However, the oncologists were only aware that 5 of the 75 patients had advance directives and only twice did the oncologists even mention advance directives. The study team asked the question, “When you are being admitted to the hospital, do you think it is important to have a discussion about advanced directives?” and 90 percent of these patients said yes. They then asked, “Are you comfortable discussing this with the team that is admitting you to the hospital that you have never met before?” and again 90 percent said yes. But when they asked the question of “Would you like to discuss this with your oncologist?” only 23 percent said yes. It turns out, he said, that for some patients and families it is easier to discuss what is going to happen to them with the referring physician than it is with the oncologist.

The lesson here, said Smith, is that somebody has to ask the two questions. It does not have to be the oncologist, but somebody needs to do it. As an example, he cited Texas Oncology, where more 80 percent of the patients have advance care planning discussions and close to 90 percent of lung cancer patients go into hospice for up to 2 months. To achieve those laudable results, Texas Oncology has made it a best practice for someone on the health care team to discuss advance care practice on a patient’s first three visits, with financial penalties for not meeting that standard. Today, US Oncology, of which Texas Oncology is an affiliate, is doing this on a regular basis in all of its practices, and Smith said US Oncology could provide the tools immediately to make this practice universal. Sanders added that these tools are available universally. He also noted that he expects that a large randomized controlled trial at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute involving all of its oncologists is going to show that these oncologists feel better about their job as doctors when they are able to have these conversations with their patients.

Sanders then said his team has interviewed African Americans in the southern United States about who they think would be the best person with which to have these conversations, and the results were mixed. The

clinicians they interviewed felt strongly that the patient’s primary care doctor would be best, while the patients thought it would be the specialist. He added that at Dana-Farber the care team is in many ways the primary medical home for their patients. “I think whoever has the ability to have this conversation well and feels most comfortable doing it should be the one to do it,” said Sanders. Meier disagreed with this idea and cited the case of Jenny C.’s doctor who was offering her futile treatment because he cared so much about her. “It would not have helped to have someone else have this discussion,” said Meier. “They will keep doing what they were trained to do because it is emotional, and it is about the relationship. It is not an easy out to just assign that job to someone else.”

Ruth Parker from Emory University School of Medicine commented that she was placing her hopes for improvement on Sanders and his generation of physicians who can now use all of the health literacy tools that her generation of researchers has developed. She then asked specifically about the role that cost transparency and people’s ability to understand the cost of care factor into decision making with regard to end-of-life care, noting that the leading cause of personal bankruptcy is medical debt. Smith replied that there are no studies looking at how people of varying levels of literacy and health literacy understand their actual cost of treatment, and there has only been one study, which he and his team published recently (Kelly et al., 2015), in which patients were given information about how much their treatment would cost. This study found that 93 percent of patients want to know up front what the cost of care would be—the other 7 percent were too ill to answer the question—and that having this 2-minute conversation with their oncologist did not destroy the physician–patient relationship.

Smith’s personal experience with patients of varying literacy, health literacy, and cultural backgrounds shows it is possible to make this information understandable. The challenge, he said, has been getting this information from his institution. “You are going to have to search at your own institution and find out what the costs are, and then you are going to have to put it in an easy-to-understand, graphical form,” said Smith. He noted that the 2013 IOM report Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis called for every health care system to be transparent about costs, but that his institution refuses to do so. When a workshop participant stated that institutions do not know what the cost of care is, Smith disagreed, and said that since November 2013 US Oncology has told every patient what the plan of treatment will cost and makes financial counselors available to help patients determine if they can afford that treatment. “That is proof positive to me that we can do this no matter who you are,” said Smith.

In Sanders’s opinion, talking about the cost of care is complex and raises health numeracy issues. He also wondered if physicians, who as a

group of people have huge student loan debt, are best equipped to talk about the cost of care in relation to benefit, and if it is even that important to talk about the cost of care with patients. “I think the changes of care that reduce cost when we elicit goals and values are patient driven, not system driven,” said Sanders. “I think that is the most important kind of cost savings.” Smith disagreed, saying that with some third-line cancer therapies costing $150,000 per month, and the average response time being 3–4 months, patients are going to want to know what their copays will be and what the benefit of that therapy will be. “That is very different than talking about a curative therapy for Hodgkin’s disease,” said Smith. “We are going to have to have these cost discussions right up front with people, no ifs, ands, or buts about it.”

In wrapping up this session, Bernard Rosof said that what he heard from speakers so far was that every member of the health care team should be trained to ask patients about what is most important to them, not only in palliative care situations but in every setting. He also heard that physicians do not want patients to think they are abandoning them and that trust and competency are core issues. Care needs to be coordinated and both patient- and family-centered. “I think these are transcending, crosscutting issues that are important not just in palliative care but in the delivery of care to patients in general,” said Rosof. While it is possible to couch these issues in terms of systems and cultures, the bottom line is that they have to do with organizational professionalism and the way health care systems treat every patient as well as with every aspect of the physician–patient relationship.