Dissemination and Implementation

The preceding chapters have described a host of findings and conclusions in the field of ovarian cancer research. The scientific evidence behind many of these findings and conclusions is robust and has been published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. This chapter addresses how these findings and conclusions are best translated into useful applications. The final step of translation is to disseminate new information and implement new interventions for multiple audiences and practice settings, whether the individuals are patients, family members, providers, advocates, health systems, payers, or other researchers. In this chapter, an overview of the science of dissemination and implementation (D&I) is presented and then applied to the research on ovarian cancers.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Roadmap initiative has been concerned not only with the translation of basic science into applied clinical trials, but also the process of the dissemination (also referred to as knowledge utilization or knowledge integration) of effective interventions into general practice (Zerhouni, 2003). The NIH has recognized that amassing evidence on risk factors, treatments, and preventive strategies is not enough to ensure that this knowledge will be effectively used. Traditionally much effort has been spent on understanding the efficacy and effectiveness of a particular intervention, while not enough has been spent on D&I, the final stage of the translational process (Khoury et al., 2007). A variety of factors must be taken into account when trying to move science into regular

and effective use, including the complexity of multiple health care systems, the capacity of active providers, and the diversity of the target audiences. Anyone involved in the D&I process must also take into account the breadth of different cultures and languages across the United States. It is clear that a “one-size-fits-all” approach will not be sufficient to translate knowledge into practice for all stakeholders. Hence, it is important that all stakeholders engaged in D&I work together to improve the dissemination of important information that can lead to improvements in ovarian cancer outcomes as a whole.

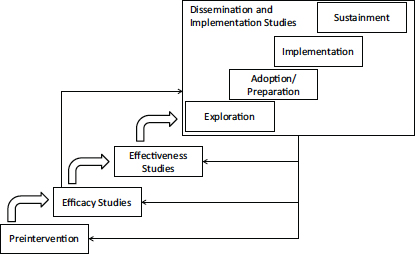

Additional stages of D&I research are needed after efficacy and effectiveness studies to ensure the integration of new knowledge into practice (see Figure 7-1). Exploration involves the identification of the audiences for which a broader application of the intervention is desirable or appropriate. Adoption involves modifying or tailoring the intervention to fit the needs of a particular target group. Implementation refers to integrating the practice or intervention in specific settings. Sustainment (or sustainability) involves scaling up the intervention and ensuring its maintenance in organizations and communities.

Dissemination is an active approach of spreading evidence-based interventions to the target audience via determined channels using planned strat-

FIGURE 7-1 Stages of research and phases of dissemination and implementation.

SOURCE: Brownson et al., 2012; NRC and IOM, 2009.

egies” (Brownson et al., 2012, p. 26) The process of dissemination involves the packaging and communication of information so that the information can most effectively be transmitted to its target audience (Lomas, 1993).

General Dissemination

The gap between knowledge generation and its application is a challenge for both clinical medicine and public health (Green et al., 2009). The diffusion of novel techniques and practices into general use does not occur spontaneously, and the unaided process is inconsistent and slow (Rogers, 2003). Moving knowledge from discovery to general use requires the active participation of multiple stakeholders (Bero et al., 1998; Bowen et al., 2009). Passive methods of dissemination such as scientific journals, practice guidelines, and mass mailings are not as effective as such methods as personal technical assistance, point-of-decision prompts, and mass media campaigns (Rabin et al., 2006). Furthermore, using individual channels of information generally proves less successful than using multiple sources of messages (Bero et al., 1998; Clancy et al., 2004). Credible sources of information are influential in convincing people to consider new ideas or topics more easily (Smith et al., 2013). However, much of human behavior is shaped by the messages and ideas presented in public health, advertising, and marketing efforts. Therefore, shaping the world’s view of a new activity or fact is in part determined by the messaging that can be found in multiple situations and settings.

The process of disseminating information or programs needs to be tailored to the unique characteristics of different audiences (e.g., age, gender, racial and ethnic background, language, and literacy level). Furthermore, readiness for change can be measured at the individual level (e.g., is an individual ready to hear and use new information?) or at an organizational level (e.g., is an organization ready to embrace a new practice or policy?), and the measured level of readiness can guide the approach used in moving the change forward (Johnson et al., 2014; Lewis et al., 2015).

Dissemination in Existing Systems

Such systems as health care organizations, hospitals or networks, workplaces, and schools are multilevel and include complex groups of people organized for a common purpose. Each system has formal and informal elements that present different opportunities and barriers to the dissemination of new or critical products and information. Researchers who seek to understand system change in health care settings have emphasized the importance of two characteristics in particular, organizational culture and climate. Organizational culture refers to the characteristics that make an

organization different from other organizations, while organizational climate is the general feel and status of the organization or group, and both are important to dissemination of research (Hsu and Marsteller, 2015). Leadership is another critical component of a system that can influence how a new idea is disseminated.

Another important factor in the dissemination of information or programs into systems is organizational readiness, which is the state of being ready to change practices or policies based on new or often external input, and represents a combination of the readiness of individuals within the system together with the necessary resources and motivation to enact the changes needed to support the innovation. Yet another factor to consider is that dissemination and innovation incurs costs, and these costs are often unknown at the beginning of the dissemination effort. Concern about costs (e.g., profitability) is one issue described as being prohibitive for the adoption of new knowledge or programs (Dearing and Kreuter, 2010). The Commonwealth Fund has developed eight strategies for systemic approaches to disseminating evidenced-based practices in national campaigns for quality improvement (The Commonwealth Fund, 2010) (see Box 7-1).

BOX 7-1

Effective Strategies for the Dissemination of Evidence-Based Practices

| Strategy 1. | Highlight the evidence base and the relative simplicity of recommended practices. |

| Strategy 2. | Align the campaign with the strategic goals of the adopting organizations. |

| Strategy 3. | Increase recruitment by integrating opinion leaders into the enrollment process and employing a nodal organizational structure. |

| Strategy 4. | Form a coalition of credible campaign sponsors. |

| Strategy 5. | Generate a threshold of participating organizations that maximizes network exchanges. |

| Strategy 6. | Develop practical implementation tools and guides for key stakeholder groups. |

| Strategy 7. | Create networks to foster learning opportunities. |

| Strategy 8. | Incorporate the monitoring and evaluation of milestones and goals. |

SOURCE: The Commonwealth Fund, 2010.

Dissemination to Providers

The main avenue of scientific dissemination to clinicians has been the scientific journal article, supplemented by presentations at national meetings and, recently, social media. Forming and publishing guidelines (see later in this chapter) was thought of as a supplemental way to focus providers on the most important ways to understand the literature and incorporate it into practice. However, such guidelines are inadequate for giving health care providers the most relevant and up-to-date information where they need it (Bero et al., 1998; Grimshaw et al., 2001). Proven alternative approaches include reminders (either manual or computerized), interactive educational meetings (e.g., workshops that include discussion or practice), and multifaceted interventions that include two or more of the following: audit and feedback, reminders, local consensus processes, or marketing (Bero et al., 1998). Passive diffusion using audiovisual materials and electronic publications, along with didactic educational meetings, is generally ineffective (Bero et al., 1998).

Enabling strategies are intended to offer providers the information and skills they need to change their practices. For example, the pharmaceutical marketing of new products to providers, also known as academic detailing, is an effective and consistent method of increasing provider uptake of new ideas or programs across multiple provider and intervention types (Fischer and Avorn, 2012). This strategy takes a marketing approach for disseminating new knowledge or programs to providers, with a mixture of one-on-one engagement, incentives, and practice consults about new findings, knowledge, or programs that could benefit providers and their patients. Other strategies offer providers the skills necessary for good practice, such as training programs in communication or consultation about a specific topic (e.g., palliative care and bereavement) (Back et al., 2008). Taken together, these methods are useful for changing an individual provider’s actions with respect to specific patient situations or types.

Dissemination to Patients and Families

A number of strategies have been used to disseminate health-related information to the general public, including national campaigns, mail, email, and the telephone (Hesse et al., 2010). Because of the increased use of electronic communication methods (e.g., smart phones), newer dissemination methods often use social media outlets and mHealth applications (Subhi et al., 2015). However, misinformation is common in websites, tweets, and other social media platforms, which leads to inaccurate ideas about health and prevention being disseminated to large audiences (Eysenbach et al., 2002).

Another way that information has been disseminated to targeted members of the public is the use of “critical others” who are in contact with the target audience. For example, in one use of a program called the 5 As (Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist, and Arrange), having health care providers deliver smoking cessation message to patients during an office visit resulted in positive outcomes (AHRQ, 2012). Strategies for delivering messages to children often use parents as the delivery system, and families of patients have been targeted as a channel for delivering information and support to those patients (Gavin et al., 2015). These existing communication channels are important social influences for health and can be effective ways to deliver new information to the right targets.

Dissemination strategies alone are insufficient to ensure the widespread use of an intervention, and so strategies for implementation are also needed (Dearing and Kreuter, 2010; Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone, 1998). Implementation is “the process of putting to use or integrating evidence-based interventions within a setting” (Brownson et al., 2012, p. 26).

General Implementation

Creating a guideline about a new fact or a finding and then disseminating that guideline to relevant providers is generally not sufficient to bring about a new practice pattern. Many levels of decision and action must change before a system implements a new practice. Knowing that the change must happen is often the first step and is often a key factor for overall change. However, many other elements of the system must change in order to produce sustainable and pervasive change. For example, many of the same variables that affect the dissemination of information in organizations are also likely to affect implementation (e.g., organizational climate, readiness, and culture). Relationships and communication among the relevant stakeholders is critical to successful implementation (Luke and Harris, 2007).

Most systems are continuously adapting to new conditions, regulations, and financing, which requires both push and pull types of change. Technologies that push people to change (“push technologies”) work best on a population level when they are directly offered, or pushed, to users. Technologies that users find and use, without any sort of external offer or encouragement are referred to as “pull technologies.” Often they are used together to compel as many people as possible to implement a new practice. Innovation and change can also come from top-down approaches, such as with the creation of a central policy that pulls the rest of the organization along with it. However, bottom-up change, where the individuals within

the system identify a problem and implement the change necessary to solve it, can also be a useful means of innovation. Both of these approaches are likely necessary for any organization that wishes to implement appropriate new ideas and programs.

Implementation is particularly complex in the clinical setting for cancer treatment, in part because there are multiple types of providers, each with relevant tasks and input into the treatment process. In the case of ovarian cancer, the gynecologic oncologist is often a key decision maker, but many others are also involved in developing a treatment plan that they all need to implement together. Beyond the oncology specialists, there are usually multiple types of medical providers and offices involved, including pathology and laboratory facilities, primary care teams, supportive care teams, and others. Often each must be involved in decisions about a single patient, and each has a role in supporting the patient through the process of treatment. In the health care setting, effective implementation of new information or interventions also needs patient engagement and involvement, along with input from families and other caregivers. Other important stakeholders include advocacy groups and members of the media, who are often left out of the process until later but are incredibly influential in shaping public opinion.

Conceptual Model of Implementation Research

Conceptual models that guide research on the processes and structures of implementation are still being developed (Tabak et al., 2012). Proctor and colleagues summarized eight processes needed to implement an innovation in a system and introduced the concept of implementation outcomes, as opposed to clinical outcomes, in order to evaluate the success of the implementation efforts themselves (Proctor et al., 2009, 2011). Damschroder and colleagues identified characteristics of the setting and innovation itself that have an impact on the implementation of new ideas into a system (Damschroder et al., 2009). Taken together, these models provide a useful starting place for considering relevant issues for the implementation of new knowledge and interventions by showing the interaction among intervention strategies, implementation strategies, and outcomes (including implementation outcomes, service outcomes, and client outcomes) (Proctor et al., 2009)

Changes in health care administration, organization, and funding may dramatically affect implementation efforts. For example, changes brought about by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act1 could revolutionize access to care, especially in states that opt for Medicaid expansion or

________________

1 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 148, 111th Cong., 2nd sess. (March 23, 2010).

other forms of population-wide provision of health care, making lack of access less of a barrier to the delivery of up-to-date information.

READY FOR DISSEMINATION AND IMPLEMENTATION

A confluence of actions is often needed if new knowledge is to be successfully translated into applications in general use. For example, the routine use of mammography for the early detection of breast cancer was implemented when imaging facilities and trained radiologists became sufficiently available, the practice was recommended by multiple guidelines groups, and its costs were paid for by both private and public insurers (Deppen et al., 2012). On the other hand, vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) for the prevention of cervical cancer proved highly effective in trials and was recommended for wide use but faced challenges in D&I because of cultural and religious beliefs in certain populations (Greenfield et al., 2015).

When Has an Issue Arrived?

One of the most complex and controversial issues in the D&I process is determining when a product, finding, or intervention is ready to be put into general practice. Individual studies are usually not sufficient. Rather, an accumulation of studies and the replication of findings, often culminating in a rigorous systematic review of the literature, is required. Individual systematic reviews are often conducted by groups of investigators; for example, the Cochrane Collaboration provides a system to summarize evidence and findings from multiple sources (Cochrane, 2015). Several guidelines (e.g., the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines) have been created to assist stakeholders in interpreting the scientific literature and in deciding about the best ways to implement new ideas for practice (Moher et al., 2009).

The guideline review process, as used by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the Community Preventive Services Task Force, makes recommendations about which clinical activities should be put into practice (Community Preventive Services Task Force, 2015; USPSTF, 2015). Clinical practice guidelines are intended to help providers (and patients) make choices about best practices, and adherence to certain guidelines is often used as a measure of the quality of cancer care. Many medical professional groups have processes for creating their own guidelines for care. In ovarian cancer, guidelines exist for screening (e.g., National Society of Genetic Counselors), clinical services (e.g., American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and Society for Gynecologic Oncology), and treatment (e.g., National Comprehensive Cancer Network) (ACOG, 2015; NCCN, 2015;

SGO, 2015). Clinical guidelines for palliative care, such as those developed by the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, are also applicable to women with ovarian cancer (NCP, 2013). Taken together, these review processes are necessary for deciding what is ready for dissemination.

What Is Already Available?

Providing information about ovarian cancer requires a wide variety of stakeholders, including federal agencies (e.g., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the NIH), private foundations, industry, academic institutions, professional societies, and advocacy groups. For example, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) provides patient-oriented information about treatment options, the effects of treatment, screening, and active research areas in ovarian cancer treatment and prevention (NCI, 2015). In addition, the NCI website describes genetic mutations and other risk factors that put women at risk for ovarian cancer. The CDC website also provides information on ovarian cancer; in particular, the website provides information on risk factors, screening, and treatment for ovarian cancer (CDC, 2015b).

The CDC created and implemented the Inside Knowledge2 media campaign to raise awareness among women and health care providers about gynecologic cancers, including cervical, ovarian, uterine, vaginal, and vulvar cancers. The campaign provides information about reliable and proven methods of prevention and early detection (e.g., Pap smears, HPV vaccination) and draws attention to symptoms and changes that could signal gynecologic cancers. By the end of 2014, the campaign had created and distributed media advertisements in digital form, used the Inside Knowledge website to deliver messages, and used print media to reach a large audience of women and their health care providers (CDC, 2015a). Between 2010 and 2014, ads produced for the Inside Knowledge campaign were seen or heard around 3.5 million times, worth a total of $136 million in donated ad value (CDC, 2015b). The CDC also investigates methods to disseminate information. For instance, the CDC found that YouTube can disseminate evidence-based information cheaply and effectively (Cooper et al., 2015).

What Is Ready for Immediate Dissemination?

Through its review of the evidence, the committee identified the following key messages and interventions ready for immediate dissemination

________________

2 For more information, see http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/knowledge (accessed September 1, 2015).

to help improve the lives of women diagnosed with or at risk for ovarian cancer (see Table 7-1):

- Ovarian cancer is not one disease.

- Current methods for early detection of ovarian cancer in the general or high-risk population do not have substantial impacts on mortality.

- Proven preventive strategies exist, and the risks and benefits need to be discussed between women who are at high risk and their health care providers.

- All women with invasive ovarian cancer should receive germline genetic testing; genetic counseling and testing are also recommended for the first-degree relatives of women with a hereditary cancer syndrome or germline mutation (i.e., cascade testing).

- Uniform implementation of the standard of care and the inclusion of supportive care across the survivorship trajectory can improve outcomes for all women with ovarian cancer.

Table 7-1 shows which messages are appropriate for different stakeholder groups and provides suggested actions for each group. Not all of these messages are appropriate for every stakeholder group. Furthermore, not all of the recommendations in this report are considered ready for D&I; some of them are rather meant to stimulate further research and direct research funding.

D&I Strategies for Specific Stakeholders in Ovarian Cancer

Specific elements of the messages in Table 7-1 can be disseminated to stakeholders right now to help reduce morbidity and mortality from ovarian cancer. The following sections provide a more detailed approach to each of the key audiences to which this report is directed. The committee describes which messages are appropriate for each of the key stakeholder groups and suggests strategies for the D&I for and by these groups.

Patients

The general public can begin to see ovarian cancer as many types of cancer, each with different risk factors and treatment patterns. Women can become more aware of the factors that may increase or decrease the risk for ovarian cancer (e.g., use of oral contraceptives) and consider whether to adopt these choices and lifestyle behaviors. Genetic counseling and testing in families with a history of ovarian, breast, or colon cancer can be a focus of discussions with providers and within families. Discussing genetic coun-

TABLE 7-1

Areas Ready for Dissemination by Each Stakeholder Group

| Key Messages | Patients | Families | Health Care Providers | Oncologists | Industry and Payers | Media and Advocacy |

| “Not one disease” (Rec. 1 & 2) | Many types of ovarian cancers | Subtypes of ovarian cancers | Treatment tailored to subtype | |||

| Genetic testing (Rec. 3 & 7a) | Ask your provider about testing | Request testing for first-degree relatives | Refer patients to testing per guidelines | Use testing results to treat and to discuss with patients | Support testing per guidelines | Testing is relevant for all patients and some families |

| Risk factors and prevention (Rec. 4 & 5) | Talk to family and provider about risks and prevention | Share family history with providers; consider oral contraceptives | ||||

| No effective approach for early detection (Rec. 6) | Need to avoid unproven and potentially invasive screening procedures | Not recommended unless high risk | Do not offer early detection procedures of unproven value | Partner with researchers to develop effective early-detection strategies | Do not advocate messages about early detection without evidence of value | |

| Standard of care (Rec. 7a & 7b) | Consider treatment at high-volume facility | Consider high-volume facility for surgery | Cover some treatment at high-volume facility | Recommend innovative treatment models | ||

| Long-term treatment (Rec. 9) | Treatment patterns differ from other cancers | Treatment is long, chronic, and debilitating | Treatment is long, chronic, and debilitating | |||

| Supportive care (Rec. 9) | Require support for broad range of care | Request support for broad range of care | Recommend palliative care | Discuss end-of-life care early in treatment | ||

seling and testing with all relevant parties might help increase the uptake of testing in high-risk populations.

General media coverage is one method of increasing knowledge in the general public, although this approach may not reach all families at high risk. More effort needs to be made to provide information to women when they are diagnosed and throughout their treatment and care. For example, several interventions and websites have been developed for use with cancer patients and families to improve information exchange and family communication, and these need to be supported in all clinical settings (Lowery et al., 2014).

Women with ovarian cancer may be unable to obtain care from specialty providers or at high-volume centers because they do not live near one of these centers or do not have direct access to such specialists. Providing women with the right questions to ask their providers could be part of the solution. These questions could generate discussion and could be the impetus for more comprehensive care for women with ovarian cancer during and after treatment.

Families

Families in which there are one or more cases of ovarian cancer need to understand the issues surrounding genetic counseling and testing and to consider methods of obtaining such testing. For first-degree relatives of women with ovarian cancer, such testing can provide either an alert of increased risk or reassurance of lower risk. Genetic counseling and testing are available through major medical centers or through direct-to-consumer companies and other sources; families are advised to consult with cancer genetics specialists before undergoing testing. Using general media alerts for these purposes might not be the most efficient method of moving information out to families. The time of diagnosis is a teachable moment for a woman to contact her family and discuss medical information, genetic counseling and testing, and risk reduction options, if appropriate.

For families of women in active treatment for ovarian cancer, understanding and planning for the long-term nature and commitment of such treatment is critical to improving the health of everyone involved with care. Families need to know that the patterns of care are inconsistent and that the treatments will likely continue over months or years. Women, their families, and their caregivers need to be aware of and knowledgeable about the physical and psychosocial sequelae of treatment. Requesting early supportive care for women might be one way that family members can ease the burden on themselves and their diagnosed relative.

Health Care Providers

Primary care providers are often in a position of evaluating the vague, nonspecific symptoms that accompany the first presentation of a woman with ovarian cancer. They are also frequently the provider responsible for the broad, long-term health needs of survivors and their families. Primary care providers, therefore, need to be alert to the common symptoms of ovarian cancer. They also need to be able to access family histories in order to help identify high-risk women and to know when they may need genetic counseling and testing or referral to a gynecologic oncology specialist. Advance care planning is meant to inform primary care providers about care preferences, but these plans are often inadequate and are not yet in full use. Requiring advance care planning at all accredited hospital and clinical facilities is one possible strategy, but the quality and content of such plans varies considerably, as does their ability to inform providers about the need for specific care over time.

Primary care providers are often the first to communicate with women about potential ovarian cancer symptoms and need to resist using unproven early-detection procedures. As more women learn about the possible symptoms of ovarian cancer, they may request screening. Primary care providers may be required to discuss why early detection is not an option with patients and explain that there is currently no endorsed method of ovarian cancer screening in the general population. Finally, primary care providers need to be up to date with the current understanding that ovarian cancer is actually a constellation of multiple diseases with different origins, pathogenesis, and prognoses.

Some of these actions require behavior change in health care providers. Convincing providers to change their medical practices is most successful when incentives are aligned with goals, when people or organizations that providers respect are used to deliver messages, and when providers are given feedback and guidance concerning how what they do with patients affects their performance and their practice quality (Damschroder et al., 2009). Changing provider behavior is often difficult, and relevant research is needed on how to raise awareness of ovarian cancer among primary care providers.

Oncology Providers

The category of oncology providers includes multiple types of providers: oncologists, pathologists, nursing and social workers, and others. Each of these specialties could benefit from disseminated information about ovarian cancer, such as learning about the existence of multiple subtypes and the need for long-term treatment and care. Surgery for ovarian cancer

is now performed in institutions with relatively low rates of ovarian cancer diagnosis and without the surgeons consulting with more highly experienced colleagues. This model of care is suboptimal. New models oriented toward obtaining high-quality surgical care at centralized medical centers (or medical centers working closely in consultation with experts) while maintaining long-term chemotherapy nearer to home need to be developed and supported by oncology providers and payers. If providers would consult with more experienced colleagues, it could improve the quality of care, so this is an option that also needs to be evaluated (Monnier et al., 2003).

As genetic testing becomes more complex and more widepsread in clinical practice, models of care need to be put into place that include clinical geneticists and genetic counselors who can inform patients and families about genetic risk. Genetics experts are often concentrated in high-volume centers, so eHealth models of care (e.g., telephone counseling), which can offer an equivalent method of delivering risk information and results that increases access and which are covered by a growing number of payors, may be an acceptable option (Kinney et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2014). Using the Internet or teleonocology could make oncologists more capable of helping care for patients in areas not located near high-volume centers (Shalowitz et al., 2015). One challenge will be how to pay for these remotely delivered services. Another challenge will be how to ensure that all providers are receiving consistent messages and adopting evidence-based practices in a comparable fashion.

Industry and Payers

The plethora of new diagnostic options and therapeutic approaches makes members of industry important stakeholders in ovarian cancer research. Companies that market genetic testing often participate directly in research, working with academicians and clinicians to develop clinically meaningful tests and methods of implementation.

Insurance industry representatives need to be aware of new recommendations for evidence-based treatments and technological applications for ovarian cancer. For example, the health insurance industry could take a lead by paying for care that uses innovative delivery models, such as a model that includes surgery at a high-volume center while covering ongoing treatment and survivorship care closer to home. Covering out-of-network surgery (i.e., surgery performed at a distant high-volume center) would be an important contribution to improving the quality of care for women with ovarian cancer.

The pharmaceutical industry plays a large role in the development and marketing of new therapeutics for ovarian cancer. Collaboration is needed among researchers, clinicians, and industry. This collaboration will likely

result in the more rapid translation of new targeted therapies that allow patients to benefit from advances in precision medicine. The development of tailored treatments for the different ovarian carcinoma subtypes will likely improve treatment outcomes for patients, but will require continued collaborative efforts.

Media and Advocacy Groups

Media and advocacy groups rely on scientific knowledge that they do not generate themselves but that drives their activities in different ways. These types of groups need to have access to a constant flow of cutting-edge information, and they need the tools to discriminate between one-time findings and emerging patterns of important practice-changing findings. Better models of bidirectional information flow, such as those being developed through PCORnet, need to be cultivated for these groups in order to better provide them with the latest scientific findings.

Currently, there is virtually no research on the challenges of D&I for ovarian cancers specifically. This is perhaps not surprising because these cancers are relatively uncommon and because there are significant gaps in the research about their etiology, risk factors, prevention, treatment, and care. This report considers the domain of ovarian cancer research as extending beyond gynecologic oncology to include the roles of primary providers, medical geneticists, epidemiologists, providers of supportive care, industry, advocacy groups, and the media. The committee identified a number of important messages for D&I, including messages about an improved understanding about the heterogeneous nature of ovarian cancers, the origins of these tumors, the value of genetic counseling and testing in high-risk women, and the effectiveness of standards of care.

As discussed previously, the committee identified key messages that are ready for immediate D&I (see Table 7-1). Unlike much of D&I in other areas of health care and prevention, these key messages are not all concerned with interventions of proven effectiveness, but also deal with important knowledge that can, if effectively applied, improve the quality of care and reduce the burden from these cancers. Cancer researchers in the field of translational research (sometimes called T3 or T4 translational research) need to engage in this challenge and explore the use of both traditional methods of communication (e.g., active multimodality educational approaches) and new technologies (e.g., social media) (Khoury et al., 2007). Stakeholders in the areas of ovarian cancer research, clinical care, and advocacy need to support new investigations and coordinate efforts

to develop and implement efficient, effective, and reliable methods for the rapid dissemination and implementation of new evidence-based information and practices. Other areas that require more research in the realm of D&I research include

- Systems for better communication of new clinically significant information and best practices to all kinds of providers;

- Systematic reviews of key elements of care and prevention;

- The movement of new treatments and issues related to care management out to the treating providers;

- The design and evaluation of new models of care for ovarian cancer patients, from initial diagnosis to end-of-life care;

- Information dissemination and practice implementation in low-resource and rural settings;

- Better inclusion of supportive care in comprehensive oncology care; and

- The engagement of the entire family at risk for developing ovarian cancer, both during treatment and in the prevention of future disease.

This chapter considers “avenues for translation and dissemination of new findings and communication of new information to patients and others” (see Box 1-1 in Chapter 1) by placing the challenge in the content of D&I research. Given the paucity of work in this area, clearly communicated messages are needed on a number of specific topics. Likewise, the committee draws attention to the need for specific D&I research in ovarian cancer to advance the science toward the ultimate goal of reducing both the mortality and morbidity of this disease.

The committee concludes that the while the knowledge base on ovarian cancers has advanced, key stakeholder groups (e.g., patients, families, providers, policy makers, advocates, researchers, and the media) are not receiving important messages that could influence patient outcomes. This may contribute to the current variability seen in the delivery of the standard of care that, in turn, affects patient outcomes. Therefore, the committee recommends the following:

RECOMMENDATION 11: Stakeholders in ovarian cancer research, clinical care, and advocacy should coordinate their efforts to develop and implement efficient, effective, and reliable methods for the rapid dissemination and implementation of evidence-based information and

practices to patients, families, health care providers, advocates, and other relevant parties. These efforts should include

- Researching impediments to adopting current evidence-based practices;

- Using multiple existing dissemination modalities (e.g., continuing education and advocacy efforts) to distribute messages strongly supported by the evidence base; and

- Evaluating newer pathways of dissemination and implementation (e.g., social media and telemedicine with specialists).

ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). 2015. Resources & publications. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications (accessed October 19, 2015).

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2012. Five major steps to intervention (the “5 A’s”). http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/5steps.html (accessed September 14, 2015).

Back, A. L., W. G. Anderson, L. Bunch, L. A. Marr, J. A. Wallace, H. B. Yang, and R. M. Arnold. 2008. Communication about cancer near the end of life. Cancer 113(7 Suppl):1897-1910.

Bero, L. A., R. Grilli, J. M. Grimshaw, E. Harvey, A. D. Oxman, and M. A. Thomson. 1998. Closing the gap between research and practice: An overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. BMJ 317(7156):465-468.

Bowen, D. J., G. Sorensen, B. J. Weiner, M. Campbell, K. Emmons, and C. Melvin. 2009. Dissemination research in cancer control: Where are we and where should we go? Cancer Causes and Control 20(4):473-485.

Brownson, R. C., G. A. Colditz, and E. K. Proctor. 2012. Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2015a. CDC’s gynecologic cancer awareness campaign campaign background. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/knowledge/pdf/cdc_ik_background.pdf (accessed September 14, 2015).

CDC. 2015b. Gynecologic cancers. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ovarian/index.htm (accessed September 22, 2015).

Clancy, C. M., J. R. Slutsky, and L. T. Patton. 2004. Evidence-based health care 2004: AHRQ moves research to translation and implementation. Health Services Research 39(5):xv-xxiii.

Cochrane. 2015. About us. http://www.cochrane.org/about-us (accessed October 18, 2015).

The Commonwealth Fund. 2010. Blueprint for the dissemination of evidence-based practices in health care. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/Files/Publications/Issue%20Brief/2010/May/1399_Bradley_blueprint_dissemination_evidencebased_practices_ib.pdf (accessed October 18, 2015).

Community Preventive Services Task Force. 2015. What is the Task Force? http://www.thecommunityguide.org/about/aboutTF.html (accessed October 18, 2015).

Cooper, C. P., C. A. Gelb, and J. Chu. 2015. Gynecologic cancer information on YouTube: Will women watch advertisements to learn more? Journal of Cancer Education. (Epub ahead of print).

Damschroder, L. J., D. C. Aron, R. E. Keith, S. R. Kirsh, J. A. Alexander, and J. C. Lowery. 2009. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science 4:50.

Dearing, J. W., and M. W. Kreuter. 2010. Designing for diffusion: How can we increase uptake of cancer communication innovations? Patient Education and Counseling 81(Suppl): S100-S110.

Deppen, S. A., M. C. Aldrich, P. Hartge, C. D. Berg, G. A. Colditz, D. B. Petitti, and R. A. Hiatt. 2012. Cancer screening: The journey from epidemiology to policy. Annals of Epidemiology 22(6):439-445.

Eysenbach, G., J. Powell, O. Kuss, and E. R. Sa. 2002. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the World Wide Web: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association 287(20):2691-2700.

Fischer, M. A., and J. Avorn. 2012. Academic detailing can play a key role in assessing and implementing comparative effectiveness research findings. Health Affairs 31(10): 2206-2212.

Gavin, L. E., J. R. Williams, M. I. Rivera, and C. R. Lachance. 2015. Programs to strengthen parent-adolescent communication about reproductive health: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 49(2 Suppl 1):S65-S72.

Green, L. W., J. M. Ottoson, C. Garcia, and R. A. Hiatt. 2009. Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Annual Review of Public Health 30:151-174.

Greenfield, L. S., L. C. Page, M. Kay, M. Li-Vollmer, C. C. Breuner, and J. S. Duchin. 2015. Strategies for increasing adolescent immunizations in diverse ethnic communities. Journal of Adolescent Health 56(5 Suppl):S47-S53.

Grimshaw, J. M., L. Shirran, R. Thomas, G. Mowatt, C. Fraser, L. Bero, R. Grilli, E. Harvey, A. Oxman, and M. A. O—Brien. 2001. Changing provider behavior: An overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Medical Care 39(8 Suppl 2):II2-II45.

Hesse, B. W., L. E. Johnson, and K. L. Davis. 2010. Extending the reach, effectiveness, and efficiency of communication: Evidence from the centers of excellence in cancer communication research. Patient Education and Counseling 81(Suppl):S1-S5.

Hsu, Y. J., and J. A. Marsteller. 2015. Who applies an intervention to influence cultural attributes in a quality improvement collaborative? Journal of Patient Safety (Epub ahead of print).

Johnson, S. S., A. L. Paiva, L. Mauriello, J. O. Prochaska, C. Redding, and W. F. Velicer. 2014. Coaction in multiple behavior change interventions: Consistency across multiple studies on weight management and obesity prevention. Health Psychology 33(5):475-480.

Khoury, M. J., M. Gwinn, P. W. Yoon, N. Dowling, C. A. Moore, and L. Bradley. 2007. The continuum of translation research in genomic medicine: How can we accelerate the appropriate integration of human genome discoveries into health care and disease prevention? Genetics in Medicine 9(10):665-674.

Kinney, A. Y., K. M. Butler, M. D. Schwartz, J. S. Mandelblatt, K. M. Boucher, L. M. Pappas, A. Gammon, W. Kohlmann, S. L. Edwards, A. M. Stroup, S. S. Buys, K. G. Flores, and R. A. Campo. 2014. Expanding access to BRCA1/2 genetic counseling with telephone delivery: A cluster randomized trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 106(12).

Lewis, C. C., B. J. Weiner, C. Stanick, and S. M. Fischer. 2015. Advancing implementation science through measure development and evaluation: A study protocol. Implemenation Science 10(1):102.

Lomas, J. 1993. Diffusion, dissemination, and implementation: Who should do what? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 703:226-235; discussion 226-237.

Lowery, J. T., N. Horick, A. Y. Kinney, D. M. Finkelstein, K. Garrett, R. W. Haile, N. M. Lindor, P. A. Newcomb, R. S. Sandler, C. Burke, D. A. Hill, and D. J. Ahnen. 2014. A randomized trial to increase colonoscopy screening in members of high-risk families in the colorectal cancer family registry and cancer genetics network. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention 23(4):601-610.

Luke, D. A., and J. K. Harris. 2007. Network analysis in public health: History, methods, and applications. Annual Review of Public Health 28:69-93.

Moher, D., A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, D. G. Altman, and P. Group. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma statement. PLoS Medicine 6(7):e1000097.

Monnier, J., R. G. Knapp, and B. C. Frueh. 2003. Recent advances in telepsychiatry: An updated review. Psychiatric Services 54(12):1604-1609.

NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network). 2015. NCCN guidelines. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp (accessed September 22, 2015).

NCI (National Cancer Institute). 2015. Ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer—for patients. http://www.cancer.gov/types/ovarian (accessed September 22, 2015).

NCP (National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care). 2013. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, 3rd ed. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care.

NRC (National Research Council) and IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2009. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Proctor, E. K., J. Landsverk, G. Aarons, D. Chambers, C. Glisson, and B. Mittman. 2009. Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 36(1):24-34.

Proctor, E., H. Silmere, R. Raghavan, P. Hovmand, G. Aarons, A. Bunger, R. Griffey, and M. Hensley. 2011. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 38(2):65-76.

Rabin, B. A., R. C. Brownson, J. F. Kerner, and R. E. Glasgow. 2006. Methodologic challenges in disseminating evidence-based interventions to promote physical activity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 31(4 Suppl):S24-S34.

Rogers, E. M. 2003. Diffusion of innovations, 5th ed. New York: Free Press.

Schwartz, M. D., H. B. Valdimarsdottir, B. N. Peshkin, J. Mandelblatt, R. Nusbaum, et al. 2014. Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 32(7):618-626.

SGO (Society for Gynecologic Oncology). 2015. Guidelines. https://www.sgo.org/clinical-practice/guidelines (accessed October 19, 2015).

Shalowitz, D. I., A. G. Smith, M. C. Bell, and R. K. Gibb. 2015. Teleoncology for gynecologic cancers. Gynecologic Oncology 139(1):172-177.

Shediac-Rizkallah, M. C., and L. R. Bone. 1998. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: Conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Education Research 13(1):87-108.

Smith, C. T., J. De Houwer, and B. A. Nosek. 2013. Consider the source: Persuasion of implicit evaluations is moderated by source credibility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 39(2):193-205.

Subhi, Y., S. H. Bube, S. R. Bojsen, A. S. S. Thomsen, and L. Konge. 2015. Expert involvement and adherence to medical evidence in medical mobile phone apps: A systematic review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 3(3):e79.

Tabak, R. G., E. C. Khoong, D. A. Chambers, and R. C. Brownson. 2012. Bridging research and practice: Models for dissemination and implementation research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43(3):337-350.

USPSTF (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force). 2015. About the USPSTF. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/about-the-uspstf (accessed October 18, 2015).

Zerhouni, E. 2003. Medicine. The NIH roadmap. Science 302(5642):63-72.