2

Increasing Private-Sector Investment in the Nonmedical Determinants of Health

Private-sector solutions to health thus far have focused almost exclusively on addressing issues of inadequate health care, said Ian Galloway, senior research associate at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. However, among the main contributors to premature death, inadequate medical care accounts for only about 10 percent. The remaining contributors to early death are environmental exposure (5 percent), behavioral patterns (40 percent), genetic predisposition (30 percent), and social circumstances (15 percent) (McGinnis et al., 2002). In his keynote address, Galloway discussed expanding the role of the private sector beyond medical care exclusively. Although it is understood that affecting the social determinants of health through community interventions reduces the likelihood of downstream medical care, investing in such interventions involves risks, he noted. The key to involving the private sector is to find ways to mitigate those risks, and to demonstrate the benefits to businesses of investing in interventions upstream that can prevent or reduce the need to invest in expensive remediation downstream. He described three examples of strategies for the private sector to invest in improving population health: corporate philanthropy, social/health entrepreneurship, and pay for success contracting. Box 2-1 provides an overview of points from Galloway’s presentation.

STRATEGIES TO LEVERAGE CORPORATE GIVING

Galloway described a context-focused approach to corporate philanthropy that leverages the existing business of the corporation, and supports the long-term goals and profitability of that business (Porter and Kramer, 2002). Businesses can make corporate grants that affect their strength, competitiveness, and bottom line in a positive way. One area that corporate philanthropy can influence is “factor conditions.” Investments in a common infrastructure, for example, enable business growth for all participants in that marketplace. More specifically, investment in a shared data infrastructure could help an insurer to support its bottom line, while also supporting the bottom line of the health industry as a whole, he explained. A second area strategic giving can influence is “demand conditions.” This involves expanding product markets through philanthropy to ultimately increase paid demand for the products in the long run. Product donations, for example, can increase the chance of achieving a critical mass of people using the products, thereby helping to demonstrate to the public their efficacy and the value in purchasing them. Corporate giving can also influence the context for “strategy and rivalry,” and help to ensure a common set of rules, incentives, and norms governing competitiveness in the local marketplace. For example, common health impact metrics to which every hospital system and health

provider is held accountable could be used by corporate philanthropy as leverage to make the industry and the marketplace more robust.

SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Social enterprises are businesses that have a social purpose, but are sustainable in the long run because they sell a product that consumers demand, Galloway explained. Social entrepreneurship is a consumer-driven approach to improve health. Sellers in social enterprises develop products that improve long-term health and reduce the need for health care. Buyers of these products are individual consumers, hospital systems, insurance companies, employers, and others. Investors provide the working capital to bring the products to market. These include banks, foundations, and impact and conventional investors. Impact investing is a relatively new concept, Galloway explained, and is estimated to account for about $46 billion in funds under international management (NAB, 2014). He described several examples of impact investing in social enterprises, including Starbucks’ Ethos® water, which donates a significant portion of its profits to fresh-water projects around the world, and TOMS® Shoes, which donates a pair of shoes to a low-income family in a developing country for every pair purchased. Impact investors expect both a social return and a financial return, as these enterprises are sustainable and do generate cash flow.

PAY FOR SUCCESS CONTRACTING

The two main elements of pay for success1 are a performance-based contract and bridge financing.

Performance-Based Contract

In a performance-based contract, a payer commits funding to a social enterprise for producing a successful outcome (e.g., an increase in kindergarten readiness, reduced childhood obesity in a neighborhood of concentrated poverty). The payer (e.g., governments, insurers, employers, hospital systems) is the consumer of the outcome. Payment is based on how much the consumer values that outcome, and the value assessment could be tied to projected cost savings for the payer. An independent impact auditor evaluates program effectiveness and determines whether

___________________

1 Galloway noted that “pay for success” is also referred to as a “social impact bond,” and the terms are used interchangeably.

the producer delivered the success as spelled out in the performance-based contract. The payer only pays for the result if it is successful.

Bridge Financing

Because payment is only made for success, this model creates a funding gap for the producer of the outcome. Typically, Galloway explained, when a problem is recognized, a request for proposals to solve that problem is issued to the social sector, and the best proposals are funded. Little discipline is built into this system, he said. Funding is for a limited time period and there is usually no follow-up to determine the success of the program in actually addressing the problem. In a pay for success model, the outcome producer needs working capital today to run its programs for however long it takes to produce the outcome. Bridge financing is provided by investors (e.g., impact investors’ banks, foundations, pension funds, endowments) who fund the service provider in exchange for a future success payment. This shifts the risk off the end payer (hospital, insurance company, government) and onto a private-sector investor. The investors bear the risk that success will not be achieved (and that the success payment will not be triggered). The financing terms of these investments vary significantly depending on the context, including the difficulty of achieving success, the track record of the service provider, and the length of the contract. Galloway noted that the shorter the contract, the more appetite among the investors. A very long contract (e.g., efforts to reduce the rate of heart disease by starting in early childhood and tracking people through age 55) will garner little interest. Based on previous experience, he said, there is a “sweet spot” in the 5- to 7-year project range.

Structuring the Deal

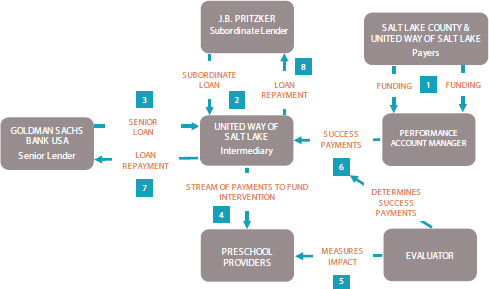

As an example of a pay for success contract, Galloway described an early childhood education intervention in Salt Lake County, Utah (see Figure 2-1). Early childhood is critical to long-term development, and disparities as a result of poor early childhood development persisting over the life course (Halfon et al., 2000; IOM, 2000). Galloway noted that the typical approach to addressing early childhood development disparities would be to provide these children with special education upon entry into kindergarten. This is a very expensive remediation, he said, and it is not necessarily the best approach for these children who would otherwise be better suited to a mainstream classroom environment.

Six hundred low-income, 3- and 4-year-old children were enrolled in the Utah High Quality Preschool Program and will have their academic

SOURCES: Galloway presentation, June 4, 2015; Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

progress tracked from grades kindergarten through 6. Children were given the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test to predict how many were very likely to need special education due to an initial learning disadvantage, and those children who tested two standard deviations below the mean were assigned to the pay for success payment group.

To provide early childhood education to all 600 children (not just those likely to need special education), $1.1 million was raised through a senior loan from Goldman Sachs, and a subordinate loan from J.B. Pritzker, an individual high net worth investor. Galloway explained that the senior loan is paid back first. Then, if money is left over, the subordinate loan is paid back. This means the subordinate investor is taking on more risk relative to the senior investor. The United Way of Salt Lake serves as the intermediary, overseeing implementation of the project and managing investor repayments.

The cost of providing special education is about $2,500 per child per year in the state of Utah. The pay for success contract was structured so that every year of avoided special education, beginning in kindergarten and through sixth grade, triggers a success payment of $2,470 per child plus 5 percent interest to Goldman Sachs and J.B. Pritzker, until both the senior and subordinate debts are fully repaid. At that point, success pay-

ments drop to $1,040 per child through sixth grade. This means the investors receive roughly all of the government savings generated up until the point where they are fully repaid. After that point, the investors split the savings with the state through the end of the contract period. Galloway pointed out that the state of Utah was supposed to be the end payer from the start, but it was unable to pass the appropriation legislation in time. Salt Lake County and the United Way of Salt Lake stepped in to serve as the payer for 1 year, after which the state of Utah did take over and will act as end payer for subsequent cohorts of children going forward.

Moving Forward with Pay for Success

With only seven projects in the United States as of June 4, 2015, pay for success is very new and still unproven, Galloway said. The projects have been relatively limited in scope, targeting prison avoidance, special education, chronic homelessness, and foster care avoidance for children born to homeless mothers. There is, however, support in the United States for the pay for success concept. A $300 million bipartisan bill now pending in Congress would set aside federal funds for technical assistance to develop deals and identify federal agencies as end payers for success. The Corporation for National and Community Service (a federal agency) recently allocated $11.2 million for technical assistance from the Social Innovation Fund. Foundations have also awarded several large grants to support pay for success projects.

INCREASING PRIVATE-SECTOR INVESTMENT

In closing, Galloway said the private sector needs to be leveraged more effectively to accomplish health aims. We tend to be hostile or skeptical of the private sector ’s ability to address the social determinants of health, he said. He advocated for increased investment by the private sector in solving problems they have never had to solve before, and suggested that the tools discussed provide a roadmap to increasing the involvement of the private sector.2

DISCUSSION

In opening the discussion, moderator Baxter agreed with Galloway that business is often treated as separate when it comes to population

___________________

2 For a broader discussion of community development, see Investing in What Works for America’s Communities. http://whatworksforamerica.org/pdf/whatworks_fullbook.pdf (accessed July 31, 2015).

health. He emphasized that business is part of the social fabric, not something outside of it. Participants commented on what drives private-sector investment, adapting pay for success to longer-term health initiatives, and some of the barriers and risks associated with pay for success.

Driving Private-Sector Investment

Galloway said private-sector investment in health is being driven forward on three fronts: investors who have become enthusiastic about investments that both make money and do good (impact investing); evidence-based social programs that solve problems; and end payers who are willing to pay for the full value of those problems being solved.

Sanne Magnan of the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement pointed out that while the health sector is very familiar with working with the performance-based contract partners (government, insurance companies, hospitals), it does not normally interact with the bridge financing partners (investors, banks, foundations, pension funds). The first step, Galloway said, is to have an actual, defined investable opportunity with a favorable return. The second step is to understand the factors that influence the different types of investors (e.g., social, regulatory, or reputational factors). Impact investors, for example, usually want to know that their money is accomplishing something good beyond just a return on their investment. A bank might be seeking Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) credit (which requires banks to invest in low-income populations in communities). Galloway acknowledged that the CRA is not particularly well equipped to reward investors in human capital projects. Baxter added that the San Francisco Federal Reserve, Kaiser Permanente, and others have been discussing how to combine the power of the CRA requirements for banks and the community benefit requirements for nonprofit hospitals around common needs/common assessments. He noted that it would be more effective to bring both to bear on a particular problem than to have them operating separately when the same determinants are at play for both.

Baxter asked whether investors are interested in randomized controlled trial designs that compare approaches. Galloway said investors are not necessarily interested in comparison studies. The end payer, however, needs to verify that the outcome promised has been delivered. In some cases this could be a straightforward before-and-after evaluation. It has to do with what they are most comfortable with and may require a high bar of proof such as a randomized controlled trial.

Adapting Pay for Success to Longer-Term Health Interventions

Baxter observed that many population health impacts take much longer to achieve than the 5- to 7-year time frame that pay for success investors seem to favor. Galloway responded that, thus far, pay for success has been used for relatively targeted interventions (e.g., a behavioral therapy program for recently released prisoners as a way to reduce recidivism). He agreed that there is a need to adapt and scale this strategy to longer-term health-related projects. He suggested that pay for success contracts could be used for neighborhood-scale comprehensive interventions in a master contracting sense. For example, New York City could enter into a pay for success contract with a large-scale nonprofit such as the Harlem Children’s Zone on a set of outcomes. The Harlem Children’s Zone is a cradle-to-college, neighborhood-based education and community-building initiative. It is expensive but effective, he said. The city could, for example, commit $50 million for every year that the childhood obesity rate in a defined community is below the city average, and crime is below the city average, and education outcomes are above the city average. On the basis of that financial commitment from the city, the Harlem Children’s Zone could then subcontract with an array of nonprofit organizations and others to deliver those outcomes.

Another approach to scale that Galloway said he is currently researching with Neal Halfon at the University of California, Los Angeles, Center for Healthier Children, Families, and Communities, is the potential for linking together pay for success projects. Building a healthy, productive, successful individual begins in the prenatal period and extends through early childhood, adolescence, teenage years, high school, college, job training, and beyond. Galloway and Halfon are exploring if a linked pay for success contract could pay for the requisite investments along the life course, and allow for the time horizons needed to accomplish real cost savings to the system (many of which are not realized until later in adulthood).

Pay for Success: Barriers and Risks

Paula Lantz of The George Washington University raised concerns about the many administrative rules, regulations, and laws that impede pay for success efforts. She acknowledged that many of these rules are in place to prevent fraud and abuse in large public programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. One challenge, for example, is that investors cannot be paid back for items that Medicaid does not pay for as part of the program (e.g., housing). Another challenge is that in this capitated environment, there cannot be shared savings. As there is a cap of 105 percent, investors could not be paid back more than 5 percent on their

original investment. Lantz and Galloway agreed that a 5 percent return on investment is not an enticing incentive for most investors to engage in pay for success with Medicaid programs.3 Galloway concurred that there are regulatory challenges across sectors in using public-sector dollars to invest upstream, and he added that moving forward will require thoughtful public-sector procurement reform. There are real opportunities for quasi-public/quasi-private entities to enter into pay for success contracts, he noted. He mentioned the coordinated care models that are coming out of the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). In Oregon, for example, the Coordinated Care Organizations (CCOs) serving the Medicaid populations in their districts are owned by private-sector corporations (e.g., health insurance companies, hospital systems). The CCOs are given a global budget to manage their Medicaid populations and are accountable for outcomes. These new CCO structures provide an example of one way to potentially invest in upstream determinants that eliminates direct public-sector contracting (i.e., is free of much of the regulatory burden that prohibits direct government contracting).

Terry Allan of the Cuyahoga County Health Department noted the challenges of defining the benefits of a pay for success program, as they can be fairly diffuse. Pay for success, in its basic form, is the idea that an investment upstream will more than pay for itself downstream in terms of reductions in cost, Galloway said. The key to making it work is identifying who the beneficiaries are of those reductions in cost (e.g., government, a health insurance company, a hospital system), and convincing them to pay for the interventions that will keep those costs from occurring. He agreed that in many cases, the benefits are diffuse and there can be a very large coalition of end beneficiaries, each with a relatively small stake in making sure the intervention works. It is very difficult to organize them around a pay for success project, and to get them to contribute their fair share, Galloway said.

In engaging a broad coalition of potential beneficiaries, Galloway cautioned against describing the investment opportunity as primarily a mechanism to save money. In many cases, success is going to accrue in other, nonbankable forms, such as efficiency gains. For example, reducing a prison population by 15 percent would reduce prison overcrowding, which is a significant problem, but it would not translate into closing any prisons, laying off guards, or eliminating pension obligations. The cash savings per inmate for no longer incarcerating them may not materialize.

___________________

3 States can apply for Medicaid Section 1115 Demonstration waivers that give them the authority to design their own experimental, demonstration, or pilot programs. See http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/Section-1115-Demonstrations.html (accessed October 12, 2015).

If an initiative is pitched as a way to save money, and at the end of the contract period success has occurred but there is no extra money, there will be disappointment in, disillusionment with, and abandonment of the pay for success mechanism. He encouraged participants to think about the end payment as the sum of all of the criteria that go into a value calculation. This means not just the downstream cost savings that may or may not actually accrue to the coalition of beneficiaries but also what the outcome is worth (e.g., the value of having a neighborhood of concentrated poverty that does not suffer from lead poisoning, or the value of a neighborhood that does not have a significant portion of low-income children with unnecessary asthma emergencies).

Claire Braeburn of America on Track asked about the financial benefits and risks for nonprofit service providers to enter into pay for success contracts. Galloway acknowledged that there is significant risk to nonprofit organizations participating in pay for success projects, and he encouraged nonprofits to be aware of the risks before entering into contracts. Pay for success is a market-based solution, and capital flows to the successful organizations and away from the unsuccessful ones. Failure can permanently affect the organization’s ability to raise further funding, even from traditional philanthropic sources. The master contracting model, where a large organization with a lot of capacity enters into relatively straightforward contracts with smaller nonprofit organizations, said Galloway, is a better model for those nonprofits that do not have the evidence base or the capacity to participate directly in pay for success.