4

Developing Human Capital in Communities

Without equity, we cannot achieve a truly healthy population at the scale needed to move toward a healthier nation overall, said moderator George Flores, program manager for The California Endowment’s Healthy California Prevention team. In this session, panelists described two programs focused on bringing people into employment and giving them opportunities to break the cycle of poverty and unemployment. These programs show how businesses can create shared value, improving the economy for themselves as well as the community at large. Carla Javits, president and CEO of REDF (the Roberts Enterprise Development Fund), discussed REDF’s portfolio of work with social enterprises that are dedicated to hiring people who face significant barriers to employment, and preparing them to enter the mainstream workforce. Farad Ali, president and CEO of The Institute,1 provided an overview of Made in Durham, a public–private partnership designed to ensure that all young people in Durham achieve their high school diploma, attain workforce training and a post-secondary credential, and have a job that pays a living wage by the age of 25. Flores then described some of the human capital development initiatives of The California Endowment, including the Building Healthy Communities initiative. Highlights from this session are in Box 4-1.

___________________

1 Formerly the North Carolina Institute of Minority Economic Development.

REDF: A BUSINESS APPROACH TO EXPANDING EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNTIES

Exclusion from the workforce has a deleterious effect on community health, Javits said. She quoted George Roberts, the founder of REDF and a key leader in the business community, who said, “If you don’t have a job you don’t have hope. If you don’t have hope, what do you really have?”2 Javits described this quote as the motto of REDF and illustrative of Roberts’ dedication to the idea of an inclusive economy for everyone. REDF was designed specifically to create jobs and employment opportu-

___________________

2 See http://redf.org/who-we-are/our-history (accessed September 15, 2015).

nities for people facing the greatest barriers to work.3 Javits also cited the work of Michael Porter at Harvard on redefining the purpose of business to be the creation of shared value (i.e., not just profit). Porter has said that shared value will drive the next wave of innovation and productivity growth in the global economy, and reshape capitalism and its relation to society (Porter and Kramer, 2011). In other words, Javits said, the businesses that compete well and win in the future are going to be those that are contributing the most to society.

The Role and Value of Social Enterprise

Social enterprises leverage a business approach to address a social mission, Javits said. She explained that a nonprofit simply doing innovative work, or a business that has a charitable campaign, is not a social enterprise. A social enterprise leverages a business approach, while making a deliberate attempt to create social value. There are social enterprises with many different social missions, such as the environment, or health products and services.

The social enterprises REDF works with are mission-driven businesses focused on hiring people who are otherwise not likely to get hired, and providing support and a pathway into the mainstream workforce. These employment social enterprises hire people who face significant barriers, including people with histories of homelessness and/or incarceration, at-risk young people who are disconnected from work and school, people with mental health disabilities or addiction issues, and other high-unemployment populations. Employment social enterprises are often run by nonprofits, but not exclusively, Javits noted. As part of the social mission, the employment social enterprise provides wages, experiential learning, and on-the-job training. Employees learn hard and soft skills while on the job, and begin to build their identity as workers. Employment is often coupled with support services. On the business side, these are revenue-generating businesses where employees create a product or provide a service for customers of those goods or services. These businesses are a vital part of the local economy and of economic development, Javits said.

Javits summarized the distinctive features of an employment social enterprise:

- Earn and reinvest their revenue to help provide more people with jobs to build skills and a career path.

___________________

3 See http://redf.org and http://webreprints.djreprints.com/3582030828345.html (accessed July 31, 2015).

- Help people who are willing and able to work, but have the hardest time getting jobs.

- Enable people to realize their full potential through a more financially sustainable and cost-effective model than many workforce development programs.

- Use a demand-driven approach to meet employer needs.

The employment social enterprise brings value to people and society in several ways. Fundamentally, chronic joblessness negatively impacts individuals, families, and communities, Javits said. Thousands of people are willing and able to work, but have a difficult time getting a job because of their background. They are literally excluded from the economy, she said. When an opportunity to work is provided to these individuals, there are economic and social benefits for the entire community. For example, these people pay taxes, bring their talent to the economy, participate in the community, foster the success of their children, change their personal behavior, and end their use of costly government programs. Employers have access to a dedicated, hard-working workforce.

Evidence of the Impact of Social Enterprises

Through the Social Innovation Fund (a federal government program that seeks to lift up promising practices and build the evidence base), REDF partnered with Mathematica Policy Research on a study of the REDF portfolio in California. The study found that of the people entering the social enterprises, 25 percent had never had a legitimate job, 85 percent had no stable housing, 70 percent had been convicted of a crime, and 71 percent of their monthly income came from government benefits (Maxwell et al., 2013). While they were in the social enterprise, support services used included assistance with food security (28 percent); avoiding relapse of behavior, such as drug use or criminal activity (25 percent); domestic abuse services (16 percent); physical health services (15 percent); substance abuse services (12 percent); and disability assistance (11 percent) (Maxwell and Rotz, 2015; Rotz et al., 2015).

In assessing employees’ outcomes, the study found increased self-sufficiency as demonstrated by a 268 percent increase in income, and a reduction of income from government entitlements and other services, from 71 percent to 24 percent. The study also found a significant increase in job retention. After 1 year, 56 percent of those hired by social enterprises were still employed, versus 37 percent of those who had only received job support services. Housing stability tripled.

A cost–benefit analysis found that for every dollar spent by the social enterprises, there is a return on investment of $2.23 in benefits to society

(through reduced public benefits, avoided incarceration, etc.). Every dollar spent saves taxpayers $1.31, and the revenue generated by the social enterprises reduces the burden on government and philanthropy to pay for programs.

The REDF Portfolio

REDF, a California-based nonprofit organization, provides capital and technical assistance to social enterprises. REDF receives a combination of funding from the federal government, individual donors, and foundations. REDF is not a social enterprise itself, Javits said, but is an intermediary that moves capital from donors and investors to social enterprises, accompanied by advisory services. She suggested that REDF is like a venture capital firm that is looking for social rather than direct financial return.

REDF is a pioneer in measuring social impact, she said, and is committed to sharing lessons learned and building a vibrant ecosystem. As noted, the mission of REDF is creating jobs and employment opportunities for people who face barriers. REDF believes the opportunity to work should be available to everyone everywhere because of the power having a job can have in transforming lives and communities. Thus far, REDF has helped nearly 10,000 people get jobs, and assisted about 60 social enterprises that have generated nearly $150 million in revenue.

Javits listed some of the social enterprises in REDF’s current and prior portfolio of investments, such as JUMA Ventures, which employs young people who face significant barriers to getting through high school and college to work ballpark concessions in partnership with Center Plate. Of those served by the REDF portfolio, the average age is 40 years, 78 percent are male, 8 percent are married, 27 percent have dependents, 4 percent are veterans, 25 percent have no high school diploma, and 57 percent are African American.

The Role of the Business Community

Javits listed elements that are needed to scale up social enterprise impact. First, there must be a market for the goods and services that the social enterprises are selling, and hiring of the people that are prepared for mainstream employment by the social enterprises. Also needed are funding for the capital costs, talent to run the social enterprises, policy to ensure a conducive environment, and “know-how” on what works best.

She highlighted some of the many companies that are already hiring from and supporting REDF’s target population in the United States. Starbucks, for example, recently launched a new entity called Leaders

Up, to work with its supply chain explicitly on the employment of at-risk youth. One hundred youth were hired as part of a pilot in Columbus, Ohio, with SK Food Group, and 80 percent were retained for 6 months, compared to the industry average of 50 percent. Javits noted that they had a 2:1 interview-to-hire ratio, where the standard in the field is 18:1. Alliance Boots recently merged with Walgreens. The United Kingdom, where Alliance Boots is based, has had an ex-offender employment initiative and has brought together about a dozen other companies in the United Kingdom to target that population. She added that internationally, employers are bolder and do more to hire people who face barriers, particularly formerly incarcerated individuals.

Companies have used a variety of models for employing individuals who face barriers, said Javits. One typical model is partnerships with local service agencies. A company partners with a nonprofit or social enterprise to recruit and develop a pipeline of trained and prepared people for the company to hire. Another approach is an in-house social enterprise, where the employer manages most of the recruitment and employment of individuals facing barriers on its own. In an outsourced staffing model, Javits said, companies work with staffing agencies that in turn collaborate with community-based organizations. The last model can be a sector-focused employer group. A group of employers from the same sector collaborate to offer training and work opportunities for individuals facing barriers, partnering with nonprofit and public agencies. Javits said this approach helps to develop the infrastructure to move the whole sector forward.

The business case for hiring workers who face barriers is that they tend to be a stronger, more loyal workforce, said Javits. Employers have access to a larger pool of talent, greater employee diversity, equal or better employee performance, and greater employee retention. The primary positive financial impact, she said, is reduced recruitment and training costs. For some of the smaller companies, there are also hiring tax credits, and wage and training subsidies. Enhanced reputation for social responsibility is also a benefit for employers, said Javits.

Moving Forward

REDF estimates about 21 million people in the United States are able and willing to work, but due to barriers such as histories of homelessness, incarceration, or disabilities, are not in the workforce. The jobless rates in these populations are 50 to 80 percent. We are losing productivity and good health, and we know we can do much better, Javits said. There are approximately 200,000 people employed in these kinds of social enterprise businesses around the country. REDF has set an aspirational goal of an additional 50,000 people employed nationally through employer

partnerships around the country. We need an ecosystem with supportive laws, rules, and practices, so that more of the people who get jobs in these companies are able to move into mainstream companies, said Javits, and find a welcoming, supportive environment. This would have a profound impact economically, and certainly for health, she concluded.

MADE IN DURHAM: BUILDING AN EDUCATION-TO-CAREER SYSTEM

Durham, North Carolina, is rich in intellectual capital, Ali said. It is the home of major universities, including Duke University and North Carolina Central University, and Research Triangle Park, with corporations such as Cisco, IBM, and Lenovo. Duke is the second largest private employer in the state behind Walmart. Each year Durham creates thousands of jobs in entertainment and media, management, social entrepreneurship, manufacturing and service, and science and technology. Employment growth in Durham will outpace the state and the country by 2021.

Not all young people in Durham have access to the tools they need to succeed in school and attain gainful employment (e.g., credentials, work-readiness skills, transportation, career knowledge, social networks). The unemployment rate for young people between ages 16 and 19 is 37 percent, and for those between ages 20 and 24, it is 15 percent. African American and Latino young people in Durham are more likely to be in prison, receive unemployment insurance, and hold labor or service positions. About 60 percent of Durham’s 44,000 youth and young adults are on track educationally (age group or advanced in path to graduate from post-secondary education and enter the workforce). Twenty-five percent are 1 or 2 years behind their age group in high school or post-secondary education. The remaining 15 percent are considered disconnected or “opportunity youth” who are far from achieving high school diplomas or work readiness, and face serious barriers to employment. Ali emphasized that low education levels are known to be linked with poor health and lower life expectancy. The challenge is to close this achievement gap and find a way to make sure those 44,000 young people are producers and not just consumers.

Made in Durham

Made in Durham is a public–private partnership to help Durham move from a patchwork of weakly aligned programs and policies to a

coherent, performance-driven, education-to-career system.4 Ali pointed out that National Academy of Medicine President, Victor Dzau, led this effort when he was chancellor for health affairs and CEO and president of the Duke University Health System, bringing together key leaders from nonprofit organizations, government, education, and community development, and CEOs from Durham’s health and life sciences, information technology, finance, and media companies.

The vision of Made in Durham is to provide all youth (on track, behind, and disconnected) with multiple educational pathways and universal work experience responsive to demand, so that they can become citizens, workers, life-long learners, and parents building healthy families in Durham (Strattan et al., 2012). The goal, Ali explained, was to create an education-to-career system where every young person completes a high school degree or equivalency, engages in work experience that will prepare each person for a career, enters post-secondary education and completes a credential, and secures a living wage by age 25. Schools have changed to meet these goals. For example, the City of Medicine Academy magnet school prepares students to graduate with their high school degree, and provides classes and field experiences that prepare them to continue their education for a career in health care.

Ali explained that Made in Durham is working to achieve its goal by embracing five principles of reform:

- Weave employment with quality education, incorporating work experiences into learning from middle school through post-secondary study.

- Engage employers and youth in the design and delivery of an education-to-career system.

- Track performance and be accountable to partners and the community, by improving data collection, analysis, and reporting.

- Bend, blend, and leverage funding.5

- Build a purposeful partnership that strengthens Durham’s existing programs and services with improved data, funding, and organizational capacity.

Employers have key roles in Made in Durham, Ali said. They serve as strategic leaders and board members, co-designers of career path-

___________________

4 See http://www.mdcinc.org (accessed July 31, 2015).

5 The goal is to achieve sustainability by relying less on new funds, to use the resources that they have more efficiently, and to prioritize where to reallocate funds. For more information on the five principles of reform, see Made in Durham: Phase 1 Action Plan 2014-2016.http://mdcinc.org/sites/default/files/resources/MID%20Action%20Plan%20Dec2014%20FINAL.pdf (accessed August 17, 2015).

ways, and critical partners in building a system that affords high-quality, applied learning and work experiences.

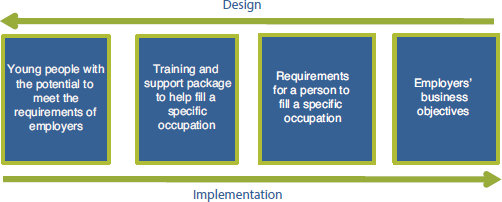

The basic model is a demand-led approach to connecting young people with good jobs. The programs were designed with the end in mind, starting with the business employer ’s objectives and working backward through the job requirements and training needed (see Figure 4-1). Work-based learning has many benefits that promote career readiness, Ali explained. For students, it helps them to make a clear connection between classroom activities and a successful career. There is also a reduction in dropout rates, and increased success rates of dropout recovery programs. For employers, work-based learning establishes a diverse talent pipeline, and reduces the cost of recruitment. Summer employment is also part of the process, helping students gain experience and make connections that can lead to full-time employment. Ali also emphasized the importance of building the soft skills that are needed to stay employed and build the relationships to get to the next level.

In closing, Ali highlighted several of the short-term outcomes from the first year of Made in Durham. The program secured 71 summer internships for young people, and established relationships with the employers to move the program forward. Employers’ perceptions of disconnected youth and how to engage with this population have changed, and several local firms have changed or amended their human resources policies to enable younger students to work. The program has also gained an increased understanding of messaging that resonates with employers, and the ability to make a strong value proposition to the business community.

SOURCES: Ali presentation, June 4, 2015; Made in Durham, 2012.

THE CALIFORNIA ENDOWMENT

The California Endowment is investing more than $1 billion, over 10 years, in its Building Healthy Communities (BHC) initiative. Investing in human capital is the main strategy to address issues of inequities in health and society, Flores said. Resident engagement (“people power”) and organizing are the roots of building human capital and the capacity for people to participate in society at large, he said. In a recent assessment, land use, safety, and school climate were the top three issue areas for resident-driven groups. Youth efforts are also extremely important to improving community health outcomes, Flores said. He referred participants to a previous Institute of Medicine roundtable workshop, which discussed the role of youth organizing, preparing youth for careers and leadership, and helping them find a pathway to participate in civil society (IOM, 2015b).

The California Endowment partnership with the Federal Reserve is bringing capital investments to BHC sites through convening stakeholders from different sectors, assessing community development needs and opportunities, and attracting and cultivating co-investors. The California Endowment is working with its long-standing partners in state and local public health and other private foundations to advance population health improvement efforts in low-income communities, including universal access to health care coverage, healthy nutrition and parks, youth development, and job training opportunities.

The California Endowment supports the California FreshWorks fund, a private–public partnership loan fund that has raised $272 million to invest in bringing grocery stores and other forms of healthy food retailers to underserved communities. Initiatives also help to support healthy consumer habits, create employment, and boost employee wages at FreshWorks-funded stores. In association with the National Executives’ Alliance and the California Executives’ Alliance, The California Endowment has led the creation of philanthropic alliances focused on lifting up men and boys of color. Partnerships with the Irvine Foundation and Atlantic Philanthropies aim to create health career pathways for underserved youth. The 14 BHC places also leverage funding for physical improvements, include building up communities and improving transportation systems so communities are more attractive to business, developing green space, and using infill development (developing vacant or underused properties in urban areas). Flores raised the issue of gentrification in terms of progress in human capital, and noted that new inequities can be an unintended result of change. Improving a community often leads to an increase in property values, resulting in higher rents that drive out some residents.

Another effort of The California Endowment is to ensure the implementation of California Proposition 47 (Prop. 47), which reclassifies cer-

tain non-serious, non-violent offenses from a felony to a misdemeanor.6 The impact of Prop. 47 is potentially significant, Flores explained, as having a felony on one’s record impacts the ability to get hired, secure housing, and receive public benefits, for example. Considering the disproportionately high rate of incarceration among young men of color and in some communities, the opportunity for them to return and be productive is a turning point for many families and neighborhoods.

Addressing Politics and Practices

In considering the breadth of ways that human capital development can be an opportunity to address inequities in communities, Flores cautioned that we cannot focus on the inequities alone, or on programs that solely compensate for inadequacies in the system. We must consider why those system inadequacies exist in the first place—politics and practices that contribute to economic inequality and the concentration of income, wealth, and power, he said. Flores asked participants to consider five questions:

- What are the underlying factors that contribute to, for example, the fact that people are more likely to go to prison than to graduate from high school in many of these places?

- Why are large portions of our population underemployed and underutilized?

- Is excessive compensation of top executives, and the growing isolation of the wealthy living in enclaves, a human capital issue that bears on population health?

- Are the proliferation of low-wage jobs and the declining bargaining power of employees human capital issues?

- Ultimately, Flores asked, why can’t “healthy business climate” mean overall prosperity shared by working people and the community at large?

DISCUSSION

During the open discussion, participants considered the association of employment with health outcomes, including mental health; funding for human capital development; the balance between education and job development training; and taking a place-based approach to health.

___________________

6 For more information see http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/resentencingunder-californias-proposition-47.html (accessed August 17, 2015).

Health Outcomes

Raymond Baxter of Kaiser Permanente observed that the connection is commonly made between economic development opportunity and health at the population level. He asked whether the individuals trying to gain access to the workforce are presenting with any particular health problems that need to be addressed, and whether successfully moving into the workforce has any impact on health at the individual level.

Javits responded that many people present with histories of addiction, mental health problems, posttraumatic stress, and, to some extent, developmental disabilities. There is often a lack of support to address these issues in the community, and because these health issues are often stigmatized, many people do not seek care. Sometimes being involved in the process of trying to get work makes people more willing to deal with these underlying health conditions that may be preventing them from succeeding in finding employment, said Javits. Evidence about the actual impact of work on health is limited and mixed, and she suggested it would be useful to study this.

Flores said there are correlations between individual health and employment in the literature, especially with jobs that have health coverage (RWJF, 2013). Employees give attention to illnesses that otherwise would have been neglected, health conditions can be addressed, and greater attention is paid to preventive care. Also, the incidences of violence and substance abuse are lower among the employed than the unemployed. Emotional health improves significantly, and rates of depression are lower among the employed. Chronic disease is also much lower among the employed than the unemployed (Oziransky et al., 2015; Witters, 2012).

A participant asked whether, at a community or population level, there is anything to suggest that the initiatives described will improve the health of the community in general. Ali said he has observed that when minority businesses are doing well, they tend to hire more minorities than any other group. Similarly, he said, women tend to hire women. People seem to have an affinity for understanding what is needed in their communal space. When there are employers who care about the community and invest in the community financially, Ali said, whether with resources or with time and commitment, there is more responsibility and respect. When there is disinvestment in communities, from grocery stores to banks and others, he added, there seems to be unrest in the communities. Javits said she has observed an impact on health from reduced incarceration, reduced homelessness, increased housing stability, increased connection to children and dependents, and the visibility of people who are working legitimate jobs in a community that has, in turn, encouraged others to get involved.

Participants discussed further the need to connect people to mental health services. Ali said that Made in Durham has no formal approach to address mental health. There is a structure to provide mentors for the young adults, and coaching to help them improve their social skills to help them stay employed. Giving them that social capital helps them to deal with some of the issues they face in getting to the next step. Javits observed that employment can provide a door to the services needed to deal with some of the issues people have in trying to get or keep a job. Because stigma persists, she said a lot more could be done so that people do not have to be marked as having a problem in order to get job development services.

Funding Alternatives

Referring back to Galloway’s keynote address (see Chapter 2), David Kindig of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health asked whether the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) or a pay for success model could be used for the development of human capital. Javits said both the CRA and pay for success offer substantial opportunities for capital to be invested in social enterprises. REDF believes that the CRA investments in social enterprises that employ people who face significant barriers to work should qualify for the CRA credit. It has been done once or twice, she said, but for the practice to spread more broadly, some banks need to be willing to take the risk to do it, and run it through the regulatory process. There are not any obvious hurdles, she said, and REDF is aware of several banks that are interested in investing in social enterprises.

Javits suggested that there are pay for success opportunities for those enterprises serving people for whom the cost and impact to government can be measured, and the success of the enterprise compellingly demonstrated in a relatively short time frame. REDF is working with the Center for Employment Opportunities, which has a pay for success agreement in New York State on the role of workforce development in preventing recidivism that builds on the findings of an earlier randomized controlled trial of the Center. Similar projects are in development elsewhere around the country.

Education Versus Employment

Sanne Magnan of the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement asked about the balance between education and job development. Javits said there is no question that having a good education, and taking people as far as they possibly can go in the education system, is essential. How-

ever, many people struggle in the education system. For many of them, employment helps to address some of the dysfunction in their lives that makes it difficult for them to get through school. Some young people who are in school also have economic responsibilities to their families. These students can benefit from closer ties between school and employment (e.g., that being done by Made in Durham).

Javits noted that in addition to jobs, people also want dignity and respect. If we act as though some of the jobs that people have are not worthy of dignity and respect, those people have difficulty fighting for proper pay and benefits.

A Place-Based Approach to Health

Terry Allan from the Cuyahoga County Board of Health said we all pay for poor health, and he asked Flores what narrative resonates in making the case for change. Flores explained that The California Endowment takes a place-based approach with the slogan “health happens here,” which signals the recognition that everything that goes on in a community matters to overall health through shared responsibility. This slogan lets people know that they can make health happen in their community, or impede health based on their practices and investments, or lack of those factors. If the community has failures or erupts into violence, all the people who live there suffer. Business is a part of the community, and is a very important piece of the place-based approach. Businesses’ employees are in that place, use the resources in that place, and serve customers in that place. Flores concluded that business should therefore consider that its own interest is being served by the welfare of that place.