5

Different Ways to Conceptualize Rural Areas in Metropolitan Society

This chapter summarizes the fifth session of the workshop on different ways to conceptualize rural areas in metropolitan society. The session was organized in two parts. The first part began with a presentation of a commissioned paper, Conceptualizing Rural America in a Metropolitan Society, by Michael Woods (University of Aberystwyth), followed by two discussants and open discussion. John Logan (Brown University) provided an urban sociologist’s point of view. Gregory Hooks (McMaster University) presented a regional inequality point of view. The second part of the session focused on the urban-rural interface as a space of integration rather than of separation, with views presented by Daniel Lichter (Cornell University) and Mark Partridge (Ohio State University). This was also followed by open discussion. David Plane was the moderator.

STATEMENT BY MICHAEL WOODS1

Woods stated that the distinction between urban and rural is one of the oldest forms of organization in history in terms of the special organization of human society. While relatively simple in the past, the precise definition of rural and urban has not always been straightforward and has become increasingly complex with the rise of metropolitan society.

He said that Landis (1940) captured the problem of fitting rural society into metropolitan society and recognized that rural America is not

_______________________

1This presentation is based on Woods (2015).

homogeneous. The problem of defining rural and urban and thinking about where rural fits into metropolitan societies is something that has been debated for some time. Part of the reason why it is problematic, he observed, is because throughout much of history, rural has been defined predominantly from an urban perspective. This can be seen in a number of ways:

- Residual definitions (i.e., remnants of urban definitions based on population size or type of land use): rural is the residual place beyond those places.

- Rural is defined in terms of accessibility to urban areas.

- Rural is defined in terms of functions performed for urban areas. Rural space provides for urban areas, whether for provision of food, fuel, or recreation.

- Rural is defined by level of development relative to urban areas, such as provision of services or issues of poverty and equality.

Wood said that each of those contexts considers the rural relative to the urban, creating methodological and conceptual problems. Apart from the methodological problems of defining the areas, the units of assessment and the problem of setting thresholds are conceptual problems of an urban perspective being predominant.

First, he said, this approach overemphasizes the homogeneity of rural areas, especially when using residual definitions, seeing rural as the residue of an urban category.

Second, he said, this approach suggests that the urban environment is the default or climactic state—defining urban land use in terms of buildings, roads, canals, and quarries implies that the only true rural land use is undeveloped. With this approach, rurality is nothing more than the state of transience between the wilderness and the city.

Third, he said with the increasing integration of rural and urban economies, cultures, and social structures, defining rural from an urban perspective leads to describing that process as urbanization because that high state of development is viewed as an urban feature. The term “urbanization of rural” is used, even though these processes may have consequences that are just as transformative in cities as they are in the country. Woods said a number of conceptual issues arise from having a predominantly urban perspective on what it means to be rural.

Analytically, he said, it presents a challenge in terms of trying to identify what the use of the rural as an analytical category was. The integration of rural and urban economics, cultures, and social structures are commonly described as “urbanization,” even though consequences may be as transformative in cities as they are in the country. This led

some geographers and others writing in the 1980s and 1990s to question relevance of the term.

Woods said it is premature to “write off” the rural. Rural still has meaning; it still has power as a brand that attracts people to buy goods because they are rural in nature. It is a category that encourages people to invest money in buying property and moving for lifestyle reasons and is a source of identity for many people. In some cases, it can lead to political mobilization to defend rural cultures and interests. There is still a potency to rural even though analysts struggle to define exactly what that rural might be.

A Rural Perspective

Woods said that he was asked to think about the place of rural in metropolitan society from a rural perspective. As Keith Halfacree said earlier in the workshop (see Chapter 3), it makes sense to start from the perspective of thinking about rural as a social construction and representation. He said these are invented categories articulated through what might be called lay discourses. Each definition is a particular discourse of reality, with public policy and media representations.

To approach this divide from a rural perspective, Woods cited Jones (1995, p. 38), who called lay discourses of rurality “all the means of intentional and incidental communication, which people use and encounter in the processes of their everyday lives, through which meanings of the rural, intentional and incidental, are expressed and constructed.” In other words, he asked, how do people who live in the countryside and engage in the countryside understand the place in which they live to be rural on an everyday basis?

Woods said that he reviewed a range of studies and reports to try to identify lay discourses of rurality and to pull out features that people refer to in order to describe the context in which they live as being rural. This is not as straightforward as statistical analysis because there is not much data. Woods said that he pulled together evidence from academic papers and studies from a number of countries, as well as journalistic accounts and exercises by foundations and interest groups. These sources present extracts from surveys of people in rural areas talking about what rural means to them; words and phrases that survey respondents felt described rural America. By definition, much of this evidence is qualitative. Few of these studies have tried to present a more quantitative summary of these statements. Focusing on some of these qualitative data, Woods identified key themes.

Landscape and Environment

The first theme is around landscape and environment, which shows some correspondence with official functional definitions. People might characterize a rural area because it is a small town, a village, or has ample space. There is also correspondence with residual definitions of rurality in terms of people seeing local areas as rural because of the absence of certain urban features from that landscape.

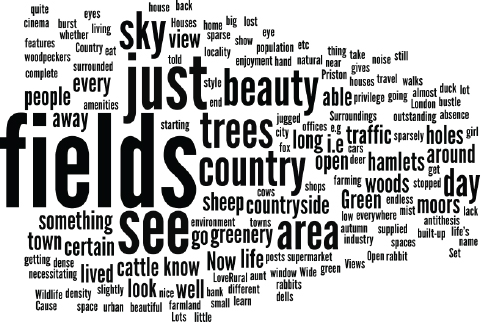

He said perhaps a more interesting observation is the positive associations of the things people see in a landscape, which to them makes it rural. To quote one rural resident in England, “the woods, the fields, the plowed fields, the sheep, the cows, the walks I go on, et cetera.” It is not necessarily just the presence of these certain features and landscape that makes something rural to the respondents, Woods pointed out. For some respondents, to be truly rural is for the respondent to have a particular knowledge of the landscape and its features. For others, the characterization of the place as rural is about being in a village, often tied to the kinds of facilities and services existing in that village. As an illustrative device, a word cloud of the relevant quotations is shown in Figure 5-1.

Agriculture and Agrarian Society

A second theme, according to Woods, is an association with agriculture and agrarian society, corresponding with some of the more formal definitions. The presence of farms, livestock, and fields were cited as why a place is rural. It goes beyond features being visible in a landscape; it is also about understanding agriculture, Woods said. As noted by a respondent to one survey,2 “Rural is as much a state of mind as an actual place. It is an acceptance and understanding of people and things living in a mainly agricultural area, the practices and traditions.” Particularly people who live on farms and work in agriculture see rural in terms of agriculture because that is the nature of their everyday lives. Woods observed that rural residents who may not have a direct involvement in agriculture talk about their encounters with agriculture as evidence that they live in a rural area. Others noted the infusion of farming through rural society. Woods noted the correspondence or resonance with the ideas of new agrarian writers in the United States about the nature of connections to the soil as the basis for rural identity, and the threat to rural identity that can come through things like the industrialization of agriculture.

_______________________

2Woods (2005, pg. 12) is quoting from Countryside Alliance, a British pressure group that represents prohunting and profarming rural interests. In 2002, they asked their members what it meant to be rural. This quote was one of the answers.

FIGURE 5-1 Word cloud summarizing responses to “What is a rural landscape?”

SOURCE: Prepared by Michael Woods (2015) for his presentation at Rationalizing Rural Area Classifications Workshop.

Community

Woods stated that a third theme identified in his analysis is about community, reflecting the importance of people and the interactions between them. It is the nature of rural society with everybody knowing everybody, everybody caring for everyone. Evidence of rural character of a place is often presented through anecdotes of social interactions and reference to involvement in community organizations and activities. These references can be a proxy for population size, but it is not the size of the population that makes a place rural. It is the form of social interactions and attributes such as feeling safe, he said.

The sense of social interaction is also associated with sets of traditions and values. People are still doing the same things in that society as 50 years ago. But community has also been associated with persistence of certain values, such as patriotism and religious values. On the other hand, he said, another narrative associates rurality with isolation and self-reliance. There is also an association in terms of tranquility and a slower pace of life. It is about peacefulness and the absence of noise.

Relative Rurality

Woods added that although people are making distinctions between rural and urban, there is recognition of relative degrees of rurality. Some places are more rural than others, and some places become less rural over time. The latter is often associated with the decline of agriculture and the dilution of community life.

The diversity of rural places means that these perspectives may be viewed differently by different people and social groups. Rural perceptions of the city emphasize crowdedness, busyness, pollution, noise, crime, and consumerism. Many long-term rural residents say that in-migrants perceive the country differently from them. But evidence suggests that difference between urban and rural perspectives is more a question of emphasis.

There are also complex mobilities of contemporary rural residents. Many people spend time moving between urban and rural space. Often when questioned, people talked about their experiences of rurality with reference to their experience of living in a city and how things were different.

Finally, Woods suggested that when talking about the urbanization of the countryside, it may be useful to think about the ruralization of the city, for example, people who work in the city during the week in order to support a lifestyle that involves going to a recreation hobby farm on the weekend. It may be useful to think about how certain urban areas or master planned estates can define themselves as villages to replicate some of the defined features of rural life in a mobile urban context. It may also be useful to think about the revival of urban agriculture, an effort that has been going on in places like Detroit, he said.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Woods questioned what happens if the attempt is made to define rural from a distinctively rural perspective. At one level, he said, there is little persuasive evidence that rural residents define the rural in significantly different ways than urban residents or urban agencies. He noted rural understandings of being rural go beyond simple definitions or lines on a map. Rural is understood primarily as a lived experience, including in ways that are more than representational. That creates a challenge in terms of translating some of this into metrics for defining rural and classifying the urban and rural. Woods concluded that the complexity of rural-urban entanglements in metropolitan society should be read not as the urbanization of the rural, but as a more complex mixing of urban and rural across space.

STATEMENT BY DISCUSSANT JOHN LOGAN

Logan provided a discussion from an urban sociologist’s point of view. He started by saying that the questions about the urban/rural continuum or how to categorize urban, rural, and the transitions between them does not have much interest for urban sociology other than from a policy perspective. The central issue for him applies equally to rural and urban areas: that is, what kinds of local environments people live in and with what consequences for their lives. He referred to earlier comments by David Plane about spatial differentiation (see Chapter 4). Localities may differ in terms of the resources and the services available, costs, access to labor market, schools, opportunities for young people, and rates of infant mortality. He said he is interested in the kinds of spatial variation that exist, and how this variation developed.

Neighborhoods

Logan said that for an urban sociologist, the neighborhood is a central concept, and the ability to measure and compare neighborhoods is crucial. Urban sociologists demand data for neighborhoods, often census tracts, and link the data to information about individuals, as in the growing neighborhood effects literature.

Logan asked about neighborhoods in rural areas. He noted the different contexts in which people live, grow up, interact, and get to know each other. However, he asked, is there anything that he would recognize as a neighborhood? For example, does spatial inequality exist on a different scale in rural from urban areas?

Logan illustrated this question by comparing research he and a colleague carried out in an urban area in Chicago with a parallel project in a rural area in Duplin County, North Carolina, organized by Barbara Entwisle. The purpose was to examine how systematic social observation can be used in each context to document the social conditions faced by residents at the “neighborhood” level. Logan noted that a key interest was in the spatial scale of neighborhood conditions, whether the neighborhood is a single street segment, an extended group of segments, a census tract, or a whole zone of the city. His project considered that the effective scale of a neighborhood is the range for which neighborhood characteristics remain roughly similar. What stood out in the Chicago study was the extent of spatial variation at very small scales, a few blocks at most.

He again questioned whether the kinds of observations in a dense urban neighborhood can also be meaningful in a rural area. The North Carolina team noted that Duplin County is a rural area, with a sparse road network and not many people. They had to decide on the unit of

observation. Unlike in the city, in a rural area one cannot just look at a street segment. One approach was to use a length of rural road as a unit for areas outside small towns. In this county, 28 percent of the rural roads from intersection to intersection are more than half mile, and more than 10 percent are more than a mile. Nevertheless, even at this large scale, an area an urbanist would not recognize as a neighborhood, there was much spatial heterogeneity.

Logan asked if these road units are the equivalent of neighborhoods in rural areas, even if “neighbors” are well out of sight of each other. What is the scale at which people’s local context matters? Logan noted a strong differentiation between the urban clusters and areas outside of a town boundary in these rural areas. The urban clusters can be identified by observing that the Census tracts are small because they have higher population density. The people are poorer, and there are higher percentages of Latinos or blacks than in the surrounding areas. The gap between the urban cluster and the rest is very significant, Logan said. Therefore, town/not town is a very important way to describe people’s living environments and opportunity structures. To some extent, if the town has its own government and tax services, the political boundary reinforces the distinction.

On the other hand, a single school district may cover the whole county and differentiation by educational opportunity is the key to local opportunity structures. In much of the country, he noted, rural counties have a single school district and maybe only one school. Probably the closest equivalent to a neighborhood in rural areas is the county because it is a meaningful political decision-making and public service unit, with boundaries that are consequential to people’s lives. But, he asked, if the county becomes the basis of community and social networks, which is the other important aspect of the neighborhood for an urban sociologist? These issues are relevant to the policy problem of how to define and categorize rural areas, he said. To understand rural America, how people live and what resources they count on, it is important to know the scale of local livelihoods and local community. If rural categories do not help in the study of such issues, they do little to advance knowledge.

STATEMENT BY DISCUSSANT GREGORY HOOKS

Hooks provided a discussion from a regional inequality point of view. He discussed challenges presently confronted by Native Americans, with a focus on reservations in rural areas.

Hooks said that American Indians and Alaska Natives fall between the cracks in federal data collection efforts. In calling attention to this failure and the organizing efforts to address it, he noted the National Congress

of American Indians makes reference to the “Asterisk Nation.”3 Neither the decennial census nor the American Community Survey (ACS) provide satisfactory information because of the difficulty of contacting individuals and high rates of nonresponse, and he said data collected by the Bureau of Indian Affairs is even worse. Tribal administrators lack information to administer programs and deliver services to tribal members and to other American Indians living in proximity to the reservation. Policy and/or social researchers have the unsatisfactory choice of excluding Native Americans from a sample or including them in a nonwhite category.

Hooks then reported on the work he and his students did assisting the Nez Perce tribe with data collection. The Nez Perce were attempting to gather data because federal data collection was so poor. The Nez Perce reservation is located in Western Idaho. The tribe serves approximately 3,500 tribal members and descendants, as well as approximately 2,100 American Indians living near the reservation who are not members of the tribe. With a relatively small population spread over a large area, the decennial census has been of little use. However with the creation of “Tribal census tracts,” the 2010 Census took initial steps to address these deficits.

His students reviewed the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) biennial Indian Labor Force Report and reported to the Nez Perce the methodology that the BIA employed in their data collection efforts. The BIA was charged by Congress in the early 1980s to conduct a survey to obtain information on the number of American Indians and their needs for purposes of developing funding formulas and other things. The data suggested improbable demographic and labor force stability over the period for the Nez Perce tribe. This was not uncommon for other tribes, he noted.

The BIA effort was based on calls to about 500 federally recognized tribes. The person answering the phone was asked how many Indians lived on the reservation, how many of them had a job, and other questions. If a respondent refused to participate or hung up the telephone, the BIA used numbers from a survey conducted two years earlier. Hooks characterized this as remarkably poor survey design. In 2009, the BIA reported that the survey did not meet federal data quality standards and began discussing strategies to improve data collection. However, since 2009, they have not published an Indian Labor Force Report.

Even if data collection were done well, providing accurate and up-to-date information on Native American populations would be challenging, Hooks said. For Native American reservations, the service population refers to American Indians, who by treaty rights have a set of services

_______________________

3See http://www.ncai.org/policy-research-center/initiatives/data-quality [November 2015].

to which the federal government has committed, but not all American Indians live on their reservations. Until the 1930s, American Indians could not leave the reservations, he pointed out. Since that time, a number of American Indians have moved around. As noted above, in the case of the Nez Perce reservation, there are about 3,000 on the reservation and approximately 2,000 American Indians who are not Nez Perce who rely on the Nez Perce tribe for a range of goods and services, including food, education, and other federally mandated services. This creates considerable challenges for Native American tribes as they lack even basic information about the population they are expected to serve.

Given the paucity of information, neither tribal administrators nor social researchers have access to the most basic of information or trends over time. There are no valid data about population, poverty, labor market activity, and other characteristics. As long as the underlying data remain imprecise, American Indians and Native Americans, especially those residing on and near rural reservations, will remain the “Asterisk Nation,” Hooks stated.

Hooks noted that although his comments are specific to American Indians and Alaska Natives, rural classification schemes can obscure other dimensions of inequality. He referred to Lichter et al. (2007), who shed light on underbounding, a process that leaves rural hamlets, typically populated by people of color and limited economic means, with diminished political voice and lacking access to basic infrastructure. This imprecision makes it difficult to study environmental inequality and other phenomena that rely on spatial precision, as he said there is reason to believe these underbounded areas face heightened environmental exposures. Another example he identified is the disproportionate building of new prisons in rural areas, distorting congressional districts by mass incarceration of urban youth who are deprived of the right to vote during and after their time in prison. Similarly, there are difficult and ongoing challenges confronting efforts to keep track of the migrant labor force in rural areas.

Hooks’ concluding message was that when thinking about rural classification, think about these populations. One of the reasons they are not counted is that their civic and political citizenship are compromised, he said. He urged that in the coming revisions to rural area classifications schemes, some of these difficult, troubling, and perverse problems can also be considered.

OPEN DISCUSSION

Woods said that what struck him with this discussion is that analysts may become a prisoner of terminology, for example, thinking about

neighborhoods. Listening to Logan, he said he was reminded of an earlier paper (Jones and Woods, 2013), in which he and his co-author focused on locality as an object of analysis with imagined coherence. They have to be meaningful to the people who live there as a community and as a space with which people identify. They have to have organizational coherence in that there is a functional space that people can use and an institutional space through which they can act. He said that made him think about neighborhoods and how the concept translates to a rural context.

In response to Woods’ presentation, Logan said his impression is people’s conceptions of rural or urban primarily reflect culture, rather than the reality of a situation, especially as rural areas become more and more heterogeneous. While there are some real divisions between rural and urban, ideas such as “everybody knows everybody” may also be true in urban neighborhoods. He said he would like a better sense of the extent to which these are cultural conceptions versus actual social interactions.

Hooks noted that a survey of what prisoners in Angola, Louisiana, would say about rural would be different from what Woods described. For Native Americans, he said rural may mean the quasi-genocidal consequences of the conquest of this continent. He also pointed out a distinction in Native American communities between urban Indians and the people who live on a reservation. Logan said the idea of a survey using word clouds was very interesting and noted it could be used to compare very small populations with the total rural population.

Woods responded that starting with the perspective of lay discourses, a diversity of opinions can emerge. He said much of what he presented was based on mainstream groups. They were strongly informed by popular culture rather than lived experience. He said that different age groups, ethnic groups, income brackets, or Native American tribes represent people with different levels of ability and experience, and these people may have very different perspectives. This indicates that there may not be a homogeneous view of what is rural. However, it is still useful to ask what makes rural important to people who live in rural areas, he said.

Ken Johnson noted some ambiguity in urban neighborhoods. Logan responded that they are not so well defined in advance. However, he said the notion of where to look for spatial boundaries, structures, and people’s opportunities in a dense urban environment is clearer than in a rural environment. Brown observed that based on his work, trying to study the factors associated with the probability of being poor in the context of rural environments, concepts such as hyper-segregation and the more sociological aspects of the buffering of social relationships, do not travel very well. The question of what is the meaningful social context that has an impact on people’s chances is very important and a challenge

for rural scholars, he said. Though there is no perfect answer in urban areas, it is easier than in a rural environment.

Halfacree noted his interest in which groups are included among rural populations, such as migrant workers. He said there are mixed responses to temporary versus permanent residents. However, he observed, the mobilities paradigm is increasingly influential in recent studies. Temporary workers living in rural areas have needs for local services and deserve to be counted, he said. At the other end of the scale is an issue about second homeowners and leisure homeowners in rural areas. They, too, are often not seen as part of a rural population, although many of them invest time and effort into rural locations. He said that today’s more fluid ideas about residency and temporariness raise questions about who should be included as the rural population.

Robert Gibbs noted that he does not know what the unit would be in U.S. rural communities to identify differences in life chances, but one of the functions of available data is to enable researchers to identify that unit. In looking at data available in rural England, hamlets are the smallest settlements and almost entirely colonized by the richest people. They have the highest life chances, and poor groups are increasingly being excluded from them. Calling it a neighborhood would be seen as the wrong term by anybody living in a rural area, he said.

STATEMENT BY DANIEL LICHTER

Lichter said he would discuss how the sociological concept of boundaries applies to the rural-urban interface, evaluate how spatial boundaries change, and highlight implied lessons for rural-urban classification systems.

Lichter quoted Lamont and Molnar (2002): “Social boundaries are objectified forms of social differences manifested in unequal access to and unequal distribution of resources (material and nonmaterial, nonmaterial being the cultural side) and social opportunities.” He applied this quotation to rural areas. Some examples of social boundaries are class boundaries, such as rich versus poor; racial boundaries, such as black versus white; disciplinary boundaries, such as economics versus sociology; and spatial boundaries, such as rural versus urban.

Changing Boundaries

Lichter described how boundaries can shift, cross, or blur:

Shifting—People move from one side of the boundary to the other, or the boundary or border changes. In the area of race, for example, there

is a large literature about white Hispanics or that Hispanics are the “new Italians.” Italians used to be defined as nonwhite but are now defined as white, he said. The white-nonwhite boundary shifted—it moved to incorporate Italians. A similar process may be under way for Hispanics, Lichter suggested.

Crossing—Boundary crossing refers to people, organizations, or places that interact with other people, organizations, or places on either side of a boundary. The boundary itself does not change but is permeable. For example, he said, some people “marry up.” They cross class boundaries by marrying someone of another class.

Blurring—The boundary between groups can become more or less bright (i.e., distinctive, or clearly defined). For example, black-white interracial marriage may result in mixed-race progeny, and the children blur the boundary between black and white. They are in a sense associational bridges between both blacks and whites. They are not easy to put on either side of the boundary.

Application to Rural-Urban Boundaries

Lichter then applied this concept to rural-urban boundaries.

Shifting—Rural is redefined as urban. This is part of the reclassification of nonmetropolitan counties and people into metropolitan counties without moving. People, by virtue of big cities gobbling up the hinterland, get redefined from rural to urban. The reclassification of rural places into urban places may occur through population growth or annexation. The people do not move or change but are redefined as part of the metropolitan population.

Crossing—Rural (and urban) people “cross” the urban-rural divide, such as commuting between rural and urban areas and interacting between the rural fringe and the urban areas. One can think of rural or urban places as “places of consumption,” where shopping, entertainment, recreation, and owning a second home take place. People cross back and forth between rural and urban areas to engage in these activities.

Urban-rural economic networks also include urban absentee owners of industry, such as coal, natural resources, or urban agriculture. He also pointed to interactions with rural areas being an urban dumping ground for hazardous waste and human populations.

Migrants are cultural carriers, Lichter said. From 2010–2013, 276,000 more people moved out of nonmetropolitan areas than moved in. It is an example of crossing rural-urban boundaries or the ruralization of urban life, or in many places the urbanization of rural life. The migration of Hispanics to new immigrant destinations is part of a global rural community.

Blurring—The line separating rural and urban areas is not clearly defined when talking about the rural-urban fringe or exurbia. Population and economic growth at the periphery make fuzzy the rural-urban divide or boundary. It is also important to talk about a regional economy and regional government where interconnected rural and urban places are part of a highly connected regional rather than just their own local economy. The boundaries between rural and urban are blurred, Lichter said.

Lessons for Rural Classification

Lichter described how the ideas of shifting, crossing, and blurring affect rural classifications. He said that it is important to note that urban influence does not just mean spatial proximity, density, or heterogeneity. Urbanism is a cultural dimension that is changing rural communities. Communities have different shares of recent in-migrants from urban areas that change the character of the community. It is important for analysts to identify the number and shares of areas (e.g., counties and places) and people who are being reclassified in either direction.

Lichter said that crossing means changing patterns of commuting between spatial categories (e.g., rural and urban). It is also possible to quantify migration between traditional spatial categories and new ones: the percentage of the population that originated from urban areas over the previous few years.

As a spatial concept, urban-rural blurring requires analyses at smaller levels of geography. At the rural periphery, different spatial units based on the Geographic Information System, such as blocks or block groups, and maps can be employed. Lichter concluded that the rural-urban boundary in the United States is dimming and becoming more ambiguous. Urbanization and urban growth continue across America, and some people argue whether there is any rural left. Rural sociology departments in universities have been redefined as development sociology or community departments. With permeable boundaries and rural and urban people operating on both sides of the spatial divide, this is an important consideration when analyzing “urban influence.” In measuring rural and urban, Lichter urged moving beyond a rural-urban continuum and talking about heterogeneity across and within each of these categories.

STATEMENT BY MARK PARTRIDGE

Partridge provided his interpretation of urban-rural interface as a space of integration rather than of separation, noting that popular opinion tends to base “rural” on landscape, density, or whether it “feels” rural. Such measures of rurality can be used for many things and various

research topics. However, he said, most regional scientists and regional/ urban economists focus on behavioral economic relationships/linkages in functional economic areas such as the effect of job growth on reducing poverty rates, incomes, employment rates, and other outcomes. This type of research needs rural classifications based on economic functions or what the “people are doing,” he said.

He provided the following example of two counties that look similar but are very different in terms of what people are doing. He noted that using a landscape measure, most of Pima County, Arizona (the non-Tucson part), and Custer County, Montana, would be observationally equivalent in terms of density, the desert, agriculture, and other characteristics. But the people behave very differently. In any population-weighted measure, virtually the whole “Census rural” population of Pima County works, shops, and acquires services in Tucson, an urban-metro cluster. For the most part, rates of growth are highest further away from urban clusters in metropolitan functional areas in the exurban and peri-urban areas. In most of Pima County, growth spreads out from the urban core. He referred to this as “low-density suburbs” in that they behaviorally act more like suburbs than rural areas. In Custer County, there are no links to urban growth. This is remote rural, he explained. Policy solutions are very different in these two areas. For economic development, urban-led economic development probably makes the most sense for residents of Pima County. For Custer County, other strategies aimed at building capacity are called for.

Partridge said rural-urban interdependence and associated spillovers are important for understanding governance, economic, cultural, and public service provision relationships. Economic linkages are well approximated by labor market commuting. If a person can commute, there are likely similar patterns for shopping, service provision, and other activities. Conceptually that means that as far as this line of research is concerned, the metropolitan area definition of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) makes sense, he said. Metropolitan areas are based on what people are functionally or actually doing. Partridge noted that most related work is at the county level because of the need to link place-of-work data (which does not make sense at lower levels of geography) with other spatial indicators. There is also the notion that Census tracts are not functional governments for policy, while counties generally are. Partridge said he also would like to see the definition of rural on a continuum from very rural to very urban. Then a question could be where to draw the line.

Observations on Rural-Urban Interdependence and Data

Partridge repeated that conceptually, OMB’s metropolitan area delineations are reasonable saying that in a French labor market study, he and colleagues found that the OMB definition worked the best of those considered in defining rural and urban labor markets.

However, he said the U.S. commuting threshold used in constructing the current OMB metropolitan area definition, 25 percent, seems low. Canada’s official definition4 uses a commuting threshold of 50 percent, although he said that seems high, because it misses “low-density suburbs” that are functionally urban. Partridge suggested a better threshold is between 25 and 50 percent. He noted that there are also multiple commuting destinations, meaning current coding is somewhat arbitrary in putting counties in one metropolitan statistical area.

Partridge said that in his work in Canada, he had successfully used Statistics Canada’s Metropolitan Influence Zones (MIZ).5 He suggested that ERS might consider something like the MIZ, for example:

- For every metropolitan/micropolitan county, create measures of moderate/strong metro area influence with a couple of delineations between 25–50 percent commuting and > 50 percent. He said this is not as arbitrary as saying all counties are equally affected by a given metro area with either an in or out criteria currently used.

- For every metropolitan/micropolitan area, create measures of weak metro area influence with a couple of delineations between 10–25 percent of commuting for nearby nonmetro counties.

- Those with less than 10 percent commuting to any metropolitan/ micropolitan area would have little/no influence from a single metro/micro area.

- Nonmetro counties with less than some arbitrary low commuting threshold to all metropolitan/micropolitan areas (say 10 percent) would be classified as no urban influence.

In summary, i–iv would be all inclusive of all U.S. counties. Partridge noted that this approach can be extended to zip codes or tracts. Finally, nonmetro counties with at least 10 percent commuting to at least two micro/metro areas would also be listed as influenced by multiple urban areas in which the specific metro/micro areas would be listed.

_______________________

4Statistics Canada census metropolitan area and census agglomeration definitions are described at http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/92-195-x/2011001/geo/cma-rmr/def-eng.htm [November 2015].

5Statistics Canada MIZ Codes are defined at http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/92195-x/2011001/other-autre/miz-zim/def-eng.htm [November 2015].

He noted Stabler and Olfert (2002) found that rising agglomeration thresholds that define the urban tiers in the hierarchy suggest similar-sized communities are serving lower levels of services than generations ago. He said it is important for research to assess whether the population threshold for defining metropolitan areas is changing over time. His sense is that a population of 50,000 no longer approximates a real agglomeration that should be classified as a metropolitan area, but rather the threshold should be raised to 75,000 or even 100,000 as Canada now does.

Multiple Tiers of Influence

Partridge stated that traditional ERS urban influence codes for nonmetropolitan counties have served researchers well. They are based on adjacency to metropolitan areas of varying sizes and their populations.6 The limitation of the traditional measures is they are arbitrary and do not reflect access to multiple levels of the urban hierarchy like central place theory. They reflect labor markets only indirectly through viewing metropolitan areas as labor markets, he noted.

One important exception is the recent ERS Frontier and Remote Area (FAR) Codes. He said the FAR Codes are good for measuring access to services at different small nonmetropolitan tiers. He said that his simple recommendation would be to aggregate the FAR to the county level so they can be more widely used.

Partridge noted that his work with Olfert, Rickman, and others used an approach to capture multiple tiers of metropolitan areas. He said that adjacency or even distance to the nearest metropolitan area misses the multiple dimensions of how agglomeration affects outcomes. It also misses how agglomeration effects attenuate over space. He said that their contribution (1) reflects that different tiers of the urban hierarchy have independent influences on outcomes and (2) reflects spatially varying distance penalties. Their example was something akin to “it matters whether you are equidistant to 10 cities of 200,000 people versus one city of 2 million” in terms of access to services, and that the distance matters as well. Partridge noted that they found that many outcomes, such as employment growth, population growth, poverty, wages, and housing/ land costs, are differentially affected by access across the entire urban hierarchy. Distance penalties were rising over time through the prerecession period. He stated that it appears that “tyranny of distance” is more about firm productivity than household amenities (Partridge et al., 2010b; RSUE).

_______________________

6Partridge stated that a good example of a study of urban influence using these measures is Wu and Gopinath (2008).

To recap, Partridge noted the importance of functional/people-based notions of determining rural when conducting economic/behavioral research. He provided his personal recommendations: augment ERS indicators to account for the threshold shortcomings in the current OMB definitions of metropolitan areas; move toward capturing differing degrees of urban influence due to labor market linkages; and create measures that reflect access across the entire urban hierarchy to capture central place theory or access beyond the reach of labor market commuting.

OPEN DISCUSSION

Woods commented that while he agreed with much of the presentations, he wondered whether the session focused on last century’s rather than this century’s questions, such as changes and linkages resulting from globalization. He asked about other kinds of relationships of areas and widened connectedness, whether to multiple metropolitan centers or to other rural areas around the world. Plane concurred, noting the interest in the 1960s about network accessibility to the rest of the whole system is important in a globalized age.

Partridge commented distance was used in multiple dimensions. He observed, as a statistical concept, that if distances became less important, they would be seen as mattering less and less over time. However, this is not the case, and analysts have found that proximity matters more and more. On the firm side, productivity issues are driving these things; firms cannot compete in rural areas, he said.

Jeffrey Hardcastle noted that, over time, retail and service patterns change, and as times change, commuting flows change. These patterns are not always static.

In terms of thresholds, Cromartie noted in 1900, the population threshold was set at 2,500. In 1950, the population threshold was moved to 50,000, which made sense given the speed of urbanization. The United States has continued urbanizing, and he said that perhaps 100,000 is not too high.

Tom Johnson agreed that the commuting threshold is very important, but noted commuting is probably becoming less important as a way of indicating the degree to which places are linked than it has in the past. He noted that it might be useful to consider the influence of where people’s second homes are located. Second homes have an important impact on the cultural connections between rural and urban.

Partridge responded that it depends on the topic of study. He noted that if he were trying to come up with an urban influence indicator, he would be interested in commuting because it proxies for many things.

However, amenities are important in describing why certain areas perform better than others.

Logan asked Lichter to respond to Partridge’s presentation about the rural-urban boundary. To Logan, the implication of the presentation is that places that are distant enough from each other have much stronger boundaries. The growth of the economies or populations are not much interconnected. Logan asked Lichter if he believed that much of rural America actually could be described as totally disconnected from urban enough to salvage the urban-rural boundary. Lichter responded that the rural-urban boundary is important, but he is trying to figure out how the sociological concept of boundaries shifting, crossing, and blurring can inform these definitions.

Partridge pointed out that he was trying to say that the commuting variable is a continuum, and a threshold could be set anywhere: 25 percent, 35 percent, and 50 percent. It would be a service if the data were available to assess the performance of different thresholds.

This page intentionally left blank.