1

Introduction

The Agent Orange Act of 1991—Public Law (PL) 102-4, enacted February 6, 1991, and codified as Section 1116 of Title 38 of the United States Code—directed the Secretary of Veterans Affairs to ask the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) to conduct an independent comprehensive review and evaluation of scientific and medical information regarding the health effects of exposure to herbicides used during military operations in Vietnam. The herbicides picloram and cacodylic acid were to be addressed, as were chemicals in various formulations that contain the herbicides 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T). Agent Orange refers specifically to a 50:50 formulation of 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T, which was stored in barrels identified by an orange band, but the term has come to often be used more generically to refer to all the herbicides sprayed by the US military in Vietnam.1 2,4,5-T contained the contaminant 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, commonly referred to as “dioxin,” which is referred to in this report as TCDD to represent a single—and the most toxic—congener of the tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxins (tetraCDDs). It should be noted that TCDD and Agent Orange are not the same. The NAS was also asked to recommend, as appropriate, additional studies to resolve continuing scientific uncertainties related to health effects and herbicide exposures and to comment on particular programs mandated in the law. The original legislation called for biennial reviews of newly available information for a period of 10

________________

1Despite loose usage of “Agent Orange” by many people, in numerous publications, and even in the title of this series, this committee uses “herbicides” to refer to the full range of herbicide exposures experienced in Vietnam, while “Agent Orange” is reserved for a specific one of the mixtures sprayed in Vietnam.

years, which was subsequently extended to 2014 by the Veterans Education and Benefits Expansion Act of 2001 (PL 107-103). This report is the final update mandated by PL 107-103.

In response to the request from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened the Committee to Review the Health Effects in Vietnam Veterans of Exposure to Herbicides. The results of the original committee’s work were published in 1994 as Veterans and Agent Orange: Health Effects of Herbicides Used in Vietnam, hereafter referred to as VAO (IOM, 1994). Successor committees formed to fulfill the requirement for updated reviews produced Veterans and Agent Orange: Update 1996 (IOM, 1996), Update 1998 (IOM, 1999), Update 2000 (IOM, 2001), Update 2002 (IOM, 2003), Update 2004 (IOM, 2005), Update 2006 (IOM, 2007), Update 2008 (IOM, 2009), Update 2010 (IOM, 2011a), and Update 2012 (IOM, 2014).

In 1999, VA asked the IOM to convene a committee to conduct an interim review of type 2 diabetes associated with exposure to any of the chemicals of interest (COIs) and this effort resulted in the report Veterans and Agent Orange: Herbicide/Dioxin Exposure and Type 2 Diabetes, hereafter referred to as Type 2 Diabetes (IOM, 2000). In 2001, VA asked the IOM to convene a committee to conduct an interim review of childhood acute myelogenous leukemia (AML, now preferably referred to as acute myeloid leukemia) associated with parental exposure to any of the COIs. The committee’s review of the literature, including literature available since the review for Update 2000, was published as Veterans and Agent Orange: Herbicide/Dioxin Exposure and Acute Myelogenous Leukemia in the Children of Vietnam Veterans, hereafter referred to as Acute Myelogenous Leukemia (IOM, 2002). In PL 107-103, passed in 2001, Congress directed the Secretary of Veterans Affairs to ask the NAS to review “available scientific literature on the effects of exposure to an herbicide agent containing dioxin on the development of respiratory cancers in humans” and to address “whether it is possible to identify a period of time after exposure to herbicides after which a presumption of service-connection” of the disease would not be warranted; the result of that effort was Veterans and Agent Orange: Length of Presumptive Period for Association Between Exposure and Respiratory Cancer, hereafter referred to as Respiratory Cancer (IOM, 2004).

In conducting their work, the committees responsible for those reports operated independently of VA and other government agencies. They were not asked to and did not make judgments regarding specific cases in which individual Vietnam veterans have claimed injury from herbicide exposure. The reports were intended to provide evidence-based assessments of the scientific information available for the Secretary of Veterans Affairs to consider as VA exercises its responsibilities to Vietnam veterans. This VAO update and all previous VAO reports are freely accessible on line at the National Academies Press’s website (http://www.nap.edu).

In accordance with PL 102-4, the committee was asked to “determine (to the extent that available scientific data permit meaningful determinations)” the following regarding associations between specific health outcomes and exposure to TCDD and other chemicals in the herbicides used by the military in Vietnam:

- whether a statistical association with herbicide exposure exists, taking into account the strength of the scientific evidence and the appropriateness of the statistical and epidemiological methods used to detect the association;

- the increased risk of the disease among those exposed to herbicides during service in the Republic of Vietnam during the Vietnam era; and

- whether there exists a plausible biological mechanism or other evidence of a causal relationship between herbicide exposure and the disease. [PL 102-4, Section 3(d)]

In addition to the request for the committee to prioritize areas for future research, which always has come with the work statement for each VAO committee, VA asked the committee for this update to address the specific question of whether service-relatedness for Parkinson disease should be interpreted to extend to all neurodegenerative diseases with Parkinson-like symptoms.

The committee notes that, as a consequence of congressional and judicial history, both its congressional mandate and the statement of task focus the target of evaluation on the “association” between exposure and health outcomes, although biologic mechanisms and causal relationships are also mentioned as part of the evaluation in Article C. As applied technically and thoroughly addressed in a report on decision making (IOM, 2008a) and in the section “Evaluation of the Evidence” in Chapter 2 of Update 2010 (IOM, 2011a), the criteria for causation do not themselves constitute a set checklist, but are more stringent than those for association. The unique mandate of VAO committees to evaluate association rather than causation means that the approach delineated in the IOM report on decision making (IOM, 2008a) is not applicable here. The rigor of the evidentiary database required to support a finding of statistical association is weaker than that required to support causality. Importantly, positive findings on any of the indicators for causality would strengthen a conclusion that an observed statistical association is reliable. In accordance with its charge, the committee examined a variety of indicators appropriate for the task, including factors commonly used to evaluate statistical associations, such as the adequacy of control for bias and confounding and the likelihood that an observed association could be explained by chance, and it assessed evidence concerning biologic plausibility derived from laboratory findings in cell culture or animal model systems. As such, a full array of indicators was used to categorize the strength of the evidence. In particular,

associations supported by multiple indicators were interpreted as having stronger scientific support.

A VA representative delivered the charge to the committee at an open session of the committee’s first meeting, and afterward the open session continued with brief presentations by other members of the public. It has been the practice of VAO committees to conduct open sessions, not only to gather additional information from people who have particular expertise on points that arise during deliberations, but also especially to listen to individual Vietnam veterans and others who are concerned about aspects of their health experience that may be service-related. Open sessions were held during the first three of the committee’s five meetings, and the agendas and the issues raised are presented in Appendix A. The comments and information provided by the public were used to identify information gaps in the literature regarding specific health outcomes of concern to Vietnam veterans.

THE CURRENT POPULATION OF VIETNAM VETERANS

In this last update in the series of reports mandated by PL 102-4 and PL 107-103, the committee wanted to make note of the number of Vietnam veterans who are still living and thus still possibly at higher risk than the general public for health consequences arising from their potential herbicide exposure in Vietnam. As discussed at some length in the original report in this series (IOM, 1994), there has been substantial dispute about exactly how many US military personnel actually served in Vietnam, with estimates ranging from 2.6 to 4.3 million (see Table 3-2 in VAO). The estimates vary in part because of various ranges of dates being used to define the Vietnam era and whether consideration is limited to those serving literally in Vietnam or includes those serving in the Vietnam theater of operations (Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and the surrounding waters). Whether female Vietnam veterans are included has little impact on the total, however, because only 5,000 to 8,000 women are thought to have served in Vietnam. In contrast to the situation for the Australian and South Korean militaries, there is no comprehensive or official roster of US Vietnam veterans, which in turn has impeded the conduct of epidemiology studies and made it difficult to track the survival of the population that is the focus of these reports.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), one of the five sources cited in VAO’s Table 3-2, has generated a succession of estimates of the number of male deployed and non-deployed Vietnam-era veterans in the civilian population from its Current Population Surveys (CPSs). The estimated age distributions of these two populations from the CPS of 1990 were presented in VAO’s Table 3-3. Since then, BLS characterized veterans in the civilian population from responses to the CPSs of 1995, 1999, 2001, and 2014, and the results for Vietnam-era veterans are presented in Table 1-1. Regrettably for this report, BLS regarded the number of Vietnam-era veterans estimated to be alive in the most recent CPS to be too small

| Year of Birth | Year of CPS Survey Age at Time of Survey | Deployed to Vietnam Theater N (%) | Non-Deployed N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | |||||

| All Ages | 3,852 | 7,938 | |||

| 1956 and after | ≤ 34 | 32 | (0.1) | 133 | (1.6) |

| 1955–1951 | 35–39 | 369 | (9.4) | 1,109 | (13.8) |

| 1950–1946 | 40–44 | 1,676 | (43.1) | 3,031 | (37.6) |

| 1945–1941 | 45–49 | 1,090 | (28.0) | 2,301 | (28.5) |

| 1940–1936 | 50–54 | 280 | (7.2) | 675 | (8.4) |

| 1935–1926 | 55–64 | 322 | (8.3) | 511 | (6.3) |

| 1925 and before | ≥ 65 | 83 | (2.1) | 178 | (2.2) |

| 1995 | |||||

| All Ages | 3,811 | 7,903 | |||

| 1960–1951 | 35–44 | 614 | (16.1) | 1,719 | (21.8) |

| 1950–1941 | 45–54 | 2,615 | (68.6) | 5,106 | (64.6) |

| 1940–1931 | 55–64 | 445 | (11.7) | 855 | (10.8) |

| 1930 and before | ≥ 65 | 137 | (3.6) | 223 | (2.8) |

| 1999a | |||||

| All Ages | 4,109 | 8,116 | |||

| 1964–1955 | 35–44 | 119 | (2.9) | 470 | (5.8) |

| 1954–1945 | 45–54 | 2,534 | (61.7) | 4,928 | (60.7) |

| 1944–1935 | 55–64 | 2,131 | (51.9) | 2,188 | (27.0) |

| 1934 and before | ≥ 65 | 326 | (7.9) | 529 | (6.5) |

| 2001 | |||||

| All Ages | 4,046 | 8,007 | |||

| 1966–1951 | 35–44 | 34 | (0.8) | 153 | (1.9) |

| 1956–1941 | 45–54 | 2,049 | (50.9) | 4,139 | (51.7) |

| 1946–1931 | 55–64 | 1,581 | (39.1) | 3,164 | (39.5) |

| 1936 and before | ≥ 65 | 382 | (9.4) | 551 | (6.9) |

| 2014b | |||||

| All Ages | 2,691 | 6,579 | |||

| 1959–1955 | 55–59b | 498 | (7.6) | ||

| 1954–1950 | 60–64b | 1,576 | (24.0) | ||

| 1949 and before | ≥ 65b | 4,505 | (68.5) | ||

aBLS could not specify any change in methodology between 1995 and 1999 that would account for the increases in the estimated totals for both deployed and non-deployed Vietnam-era veterans in the civilian population, so the committee assumes that the increase is due to a large number of retirements from the military during that period.

bBecause of decreasing totals, age brackets were not calculated separately for deployed and non-deployed Vietnam veterans.

SOURCES: BLS, 1990, 1995, 1999, 2001, 2014.

to permit estimating the age distributions separately for deployed and non-deployed veterans, but the total number of surviving deployed veterans represented 29.0 percent of living male Vietnam-era veterans. The comparable proportion had been 32.7 percent in the 1990 CPS and 28.1 percent and 24.5 percent in earlier estimates of DOD (1976) and VA (1985), respectively, suggesting that deployed and non-deployed Vietnam-era veterans have not experienced dramatically different mortality rates.

CONCLUSIONS OF PREVIOUS

VETERANS AND AGENT ORANGE REPORTS

Health Outcomes

VAO, Update 1996, Update 1998, Update 2000, Update 2002, Update 2004, Type 2 Diabetes, Acute Myelogenous Leukemia, Respiratory Cancer, Update 2006, Update 2008, Update 2010, and Update 2012 contain detailed reviews of the scientific studies evaluated by the committees and their implications for cancers, reproductive and developmental effects, neurologic disorders, and other health effects.

The original VAO committee addressed the statutory mandate to evaluate the association between herbicide exposure and individual health conditions by assigning each of the health outcomes under study to one of four categories on the basis of the epidemiologic evidence reviewed. The categories were adapted from the ones used by the International Agency for Research on Cancer in evaluating evidence of the carcinogenicity of various substances (IARC, 1977). Successor VAO committees adopted the same categories, and these are described below.

The question of whether the committee should be considering statistical association rather than causality has been debated. In legal proceedings that predated passage of the legislation that mandated the VAO series of reviews, Nehmer v. United States Department of Veterans Affairs found that

the legislative history, and prior VA and congressional practice, support our finding that Congress intended that the Administrator predicate service connection upon a finding of a significant statistical association between dioxin exposure and various diseases. We hold that the VA erred by requiring proof of a causal relationship. [712 F. Supp. 1404, 1989]

The committee believes that the categorization of strength of evidence as shown in Table 1-2 is consistent with that court ruling. In particular, the ruling does not preclude the consideration of the factors usually assessed in determining a causal relationship (Hill, 1965; IOM, 2008a) as indicators of the strength of scientific evidence of an association. In accordance with the court ruling, the

committee was not seeking proof of a causal relationship, but any information that supports a causal relationship, such as a plausible biologic mechanism as specified in Article C of the charge to the committee, would also lend credence to the reliability of an observed association. An understanding of causal relationships is the ultimate objective of science, whereas the committee’s goal of assessing statistical association is an intermediate point along the continuum between no association and causality.

The categories, the criteria for assigning a particular health outcome to a category, and the health outcomes that have been assigned to the categories in past updates are discussed below. Table 1-2 summarizes the conclusions of Update 2012 regarding associations between health outcomes and exposure to the herbicides used in Vietnam or to any of their components or contaminants. That integration of the literature through September 2012 served as the starting point for the current committee’s deliberations. The categories of association concern the occurrence of health outcomes in human populations in relation to chemical exposure. As such, the categorizations do not address the likelihood that any one individual’s health problem is associated with, or caused by, the chemicals in question.

Health Outcomes with Sufficient Evidence of an Association

For a health outcome to be placed in the category “health outcomes with sufficient evidence of an association,” a positive association between herbicides and the outcome must be observed in epidemiologic studies in which chance, bias, and confounding can be ruled out with reasonable confidence. The committee regarded evidence from several studies that satisfactorily addressed bias and confounding and that showed an association that is consistent in magnitude and direction to be sufficient evidence of an association. Experimental data supporting biologic plausibility strengthen evidence of an association, but are not a prerequisite and are not enough to establish an association without corresponding epidemiologic findings.

The original VAO committee found sufficient evidence of an association between exposure to herbicides and three cancers—soft-tissue sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma—and two other health outcomes, chloracne and porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT). After reviewing all the literature available in 1995, the committee responsible for Update 1996 concluded that the statistical evidence still supported that classification for the three cancers and chloracne, but that the evidence of an association with PCT warranted its being placed in the category of limited or suggestive evidence of an association with exposure.

As the committee responsible for Update 2002 began its work, VA requested that it evaluate whether chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) should be considered separately from other leukemias. That committee concluded that CLL could

TABLE 1-2 Summary of Ninth Biennial Update of Findings on Vietnam-Veteran, Occupational, and Environmental Studies Regarding Scientifically Relevant Associationsa Between Exposure to Herbicides and Specific Health Outcomesb

| Sufficient Evidence of an Association | |

| Epidemiologic evidence is sufficient to conclude that there is a positive association. That is, a positive association has been observed between exposure to herbicides and the outcome in studies in which chance, bias, and confounding could be ruled out with reasonable confidence.c For example, if several small studies that are free of bias and confounding show an association that is consistent in magnitude and direction, then there could be sufficient evidence of an association. There is sufficient evidence of an association between exposure to the chemicals of interest and the following health outcomes: | |

| Soft-tissue sarcoma (including heart) | |

| Soft-tissue sarcoma (including heart) | |

|

* Non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

|

|

* Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (including hairy cell leukemia and other chronic B-cell leukemias) |

|

|

* Hodgkin lymphoma |

|

| Chloracne | |

| Limited or Suggestive Evidence of an Association | |

| Epidemiologic evidence suggests an association between exposure to herbicides and the outcome, but a firm conclusion is limited because chance, bias, and confounding could not be ruled out with confidence.b For example, a well-conducted study with strong findings in accordance with less compelling results from studies of populations with similar exposures could constitute such evidence. There is limited or suggestive evidence of an association between exposure to the chemicals of interest and the following health outcomes: | |

| Laryngeal cancer | |

| Cancer of the lung, bronchus, or trachea | |

| Prostate cancer | |

|

* Multiple myeloma |

|

|

* AL amyloidosis |

|

| Early-onset peripheral neuropathy | |

| Parkinson disease | |

| Porphyria cutanea tarda | |

| Hypertension | |

| Ischemic heart disease | |

| Stroke (category change from Update 2010) | |

| Type 2 diabetes (mellitus) | |

| Spina bifida in offspring of exposed people | |

| Inadequate or Insufficient Evidence to Determine an Association | |

| The available epidemiologic studies are of insufficient quality, consistency, or statistical power to permit a conclusion regarding the presence or absence of an association. For example, studies fail to control for confounding, have inadequate exposure assessment, or fail to address latency. There is inadequate or insufficient evidence to determine association between exposure to the chemicals of interest and the following health outcomes that were explicitly reviewed: | |

|

Cancers of the oral cavity (including lips and tongue), pharynx (including tonsils), or nasal cavity (including ears and sinuses) |

|

|

Cancers of the pleura, mediastinum, and other unspecified sites in the respiratory system and intrathoracic organs |

|

|

Esophageal cancer |

|

|

Stomach cancer |

|

|

Colorectal cancer (including small intestine and anus) |

|

|

Hepatobiliary cancers (liver, gallbladder, and bile ducts) |

|

|

Pancreatic cancer |

|

|

Bone and joint cancer |

|

|

Melanoma |

|

|

Non-melanoma skin cancer (basal-cell and squamous-cell) |

|

|

Breast cancer |

|

|

Cancers of reproductive organs (cervix, uterus, ovary, testes, and penis; excluding prostate) |

|

|

Urinary bladder cancer |

|

|

Renal cancer (kidney and renal pelvis) |

|

|

Cancers of brain and nervous system (including eye) |

|

|

Endocrine cancers (thyroid, thymus, and other endocrine organs) |

|

|

Leukemia (other than chronic B-cell leukemias, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia and hairy cell leukemia) |

|

|

Cancers at other and unspecified sites |

|

|

Infertility |

|

|

Spontaneous abortion (other than after paternal exposure to TCDD, which appears not to be associated) |

|

|

Neonatal or infant death and stillbirth in offspring of exposed people |

|

|

Low birth weight in offspring of exposed people |

|

|

Birth defects (other than spina bifida) in offspring of exposed people |

|

|

Childhood cancer (including acute myeloid leukemia) in offspring of exposed people |

|

|

Neurobehavioral disorders (cognitive and neuropsychiatric) |

|

|

Neurodegenerative diseases, excluding Parkinson disease |

|

|

Chronic peripheral nervous system disorders |

|

|

Hearing loss |

|

|

Respiratory disorders (wheeze or asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and farmer’s lung) |

|

|

Gastrointestinal, metabolic, and digestive disorders (changes in hepatic enzymes, lipid abnormalities, and ulcers) |

|

|

Immune system disorders (immune suppression, allergy, and autoimmunity) |

|

|

Circulatory disorders (other than hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and stroke) |

|

|

Endometriosis |

|

|

Disruption of thyroid homeostasis |

|

|

Eye problems |

|

|

Bone conditions |

|

| This committee used a classification that spans the full array of cancers. However, reviews for nonmalignant conditions were conducted only if they were found to have been the subjects of epidemiologic investigation or at the request of the Department of Veterans Affairs. By default, any health outcome on which no epidemiologic information has been found falls into this category. | |

| Limited or Suggestive Evidence of No Association | |

| Several adequate studies, which cover the full range of human exposure, are consistent in not showing a positive association between any magnitude of exposure to a component of the herbicides of interest and the outcome. A conclusion of “no association” is inevitably limited to the conditions, exposures, and length of observation covered by the available studies. In addition, the possibility of a very small increase in risk at the exposure studied can never be excluded. There is limited or suggestive evidence of no association between exposure to the herbicide component of interest and the following health outcome: | |

| Spontaneous abortion after paternal exposure to TCDD | |

aThis change in wording was made to emphasize the scientific nature of the VAO task and procedures and reflects no change in the present committee’s criteria from those used in previous updates.

bHerbicides indicates the following chemicals of interest: 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T) and its contaminant 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD or dioxin), cacodylic acid, and picloram. The evidence regarding association was drawn from occupational, environmental, and veteran studies in which people were exposed to the herbicides used in Vietnam, to their components, or to their contaminants.

cEvidence of an association is strengthened by experimental data supporting biologic plausibility, but its absence would not detract from the epidemiologic evidence.

*The committee notes the consistency of these findings with the biologic understanding of the clonal derivation of lymphohematopoietic cancers that is the basis of the World Health Organization classification system (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3109529/table/T1, accessed December 2, 2015).

be considered separately and, on the basis of the epidemiologic literature and the etiology of the disease, placed CLL in the “sufficient” category. In response to a request from VA, the committee for Update 2008 affirmed that hairy-cell leukemia belonged in the category of sufficient evidence of an association along with the related conditions CLL and chronic B-cell lymphomas.

Health Outcomes with Limited or Suggestive Evidence of an Association

In the category of “health outcomes with limited or suggestive evidence of an association,” the evidence must suggest an association between exposure to herbicides and the outcome considered, but the evidence can be limited by the inability to rule out chance, bias, or confounding confidently. The coherence of the full body of epidemiologic information, in light of biologic plausibility, is considered when the committee reaches a judgment about association for a given outcome. Because the VAO series has a number of agents of concern whose toxicity profiles are not expected to be uniform—specifically, four herbicides and TCDD—apparent inconsistencies can be expected among study populations that have experienced different exposures. Even for a single exposure, a spectrum

of results would be expected, depending on the power of the studies, inherent biological relationships, and other study design factors.

The committee responsible for VAO found limited or suggestive evidence of an association between exposure to herbicides and three categories of cancer: respiratory cancers (after individual evaluations of laryngeal cancer and of cancers of the trachea, lung, or bronchus), prostate cancer, and multiple myeloma. The Update 1996 committee added three health outcomes to the list: PCT, acute and subacute peripheral neuropathy (indicated as early-onset transient peripheral neuropathy after Update 2004 and then re-specified as simply early-onset peripheral neuropathy after Update 2010), and spina bifida in children of veterans. Initially, transient peripheral neuropathies had not been addressed in VAO, because they are not amenable to epidemiologic study. In response to a VA request, however, the Update 1996 committee reviewed those neuropathies and based its determination on case histories. A combination of a 1995 report of birth defects among the offspring of veterans who served in Operation Ranch Hand and results of earlier studies of neural-tube defects in the children of Vietnam veterans (published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) led the Update 1996 committee to distinguish spina bifida from other reproductive outcomes and to place it in the “limited or suggestive evidence” category.

After the publication of Update 1998, the committee responsible for Type 2 Diabetes, on the basis of its evaluation of newly available scientific evidence and the cumulative findings of research that had been reviewed in previous VAO reports, concluded that there was limited or suggestive evidence of an association between exposure to the herbicides used in Vietnam or the contaminant TCDD and type 2 diabetes (mellitus).

The committee responsible for Update 2000 reviewed the material in earlier reports and the newly published literature and determined that there was limited or suggestive evidence of an association between exposure to herbicides used in Vietnam or the contaminant TCDD and AML in the children of Vietnam veterans. After the release of Update 2000, the researchers for one of the reviewed studies discovered an error in their published data. The committee for Update 2000 was reconvened to re-evaluate the previously reviewed and new literature regarding AML, and it produced Acute Myelogenous Leukemia, which reclassified AML in children from “limited or suggestive evidence of an association” to “inadequate or insufficient evidence to determine an association.”

After reviewing the data reviewed in previous VAO reports and recently published scientific literature, the committee responsible for Update 2006 determined that there was limited or suggestive evidence of an association between exposure to the herbicides used in Vietnam or the contaminant TCDD and hypertension. Amyloid light-chain (AL) amyloidosis was also moved to the category of “limited or suggestive evidence of an association,” primarily on the basis of its close biologic relationship with multiple myeloma.

With a bit more consistent epidemiologic data augmented by an increased understanding of the mechanisms that new toxicology research had offered, the committee for Update 2008 was able to resolve the Update 2006 committee’s lack of consensus and moved ischemic heart disease into the limited or suggestive category, joining hypertension. New studies of Parkinson disease that yielded findings of an association with the specific herbicides of interest were deemed to move the evidence to the category of limited or suggestive.

The committee for Update 2012 determined that there was limited or suggestive evidence of an association of stroke with exposure to the herbicides used in Vietnam. A new finding of a strong association between serum concentrations of dioxin-like chemicals and the risk of stroke complemented earlier observations in important veteran, occupational, and environmental cohorts to make a compelling set of positive evidence.

Health Outcomes with Inadequate or Insufficient

Evidence to Determine an Association

By default, any health outcome is in the category of “health outcomes with inadequate or insufficient evidence to determine an association” before enough reliable scientific data have accumulated to promote it to the category of sufficient evidence or limited or suggestive evidence of an association or to move it to the category of limited or suggestive evidence of no association. In this category, the available studies may have inconsistent findings or be of insufficient quality or statistical power to support a conclusion regarding the presence of an association. Such studies might have failed to control for confounding factors or might have had inadequate assessment of exposure.

The cancers and other health effects so categorized in Update 2012 are listed in Table 1-2, but several health effects have been moved into or out of this category since the original VAO committee reviewed the evidence then available. Skin cancers were moved into this category in Update 1996 when inclusion of new evidence no longer supported its classification as a condition with limited or suggestive evidence of no association. Similarly, the Update 1998 committee moved urinary bladder cancer from the category of limited or suggestive evidence of no association to this category; in that case, although there was no evidence that exposure to herbicides or TCDD was related to urinary bladder cancer, newly available evidence weakened the evidence of no association. The committee for Update 2000 had split off AML in the offspring of Vietnam veterans from other childhood cancers and put it into the category of suggestive evidence but a separate review, as reported in Acute Myelogenous Leukemia, found errors in the published information and returned it to this category with other childhood cancers. In Update 2002, CLL was moved from this category to join Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the category of sufficient evidence of an association.

The committee responsible for Update 2006 moved several cancers (of the brain, stomach, colon, rectum, and pancreas) from the category of limited or suggestive evidence of no association into this category partly because of some changes in evidence since they were originally placed in the “no association” category but primarily because that committee had concerns about the lack of information on all five COIs and each of these cancers.

Health Outcomes with Limited or Suggestive Evidence of No Association

The original VAO committee defined the category “health outcomes with limited or suggestive evidence of no association” for health outcomes for which several adequate studies covering the “full range of human exposure” were consistent in showing no association with exposure to herbicides at any concentration and had relatively narrow confidence intervals. A conclusion of “no association” is inevitably limited to the conditions, exposures, and observation periods covered by the available studies, and the possibility of a small increase in risk related to the magnitude of exposure studied can never be excluded. However, a change in classification from inadequate or insufficient evidence of an association to limited or suggestive evidence of no association would require new studies that correct for the methodologic problems of previous studies and that have samples large enough to limit the possible study results attributable to chance.

The original VAO committee found a sufficient number and variety of well-designed studies to conclude that there was limited or suggestive evidence of no association between the exposures of interest and a small group of cancers: gastrointestinal tumors (colon, rectum, stomach, and pancreas), skin cancers, brain tumors, and urinary bladder cancer. The Update 1996 committee removed skin cancers and the Update 1998 committee removed urinary bladder cancer from this category because the evidence no longer supported a conclusion of no association. The Update 2002 committee concluded that there was adequate evidence to determine that spontaneous abortion is not associated with paternal exposure specifically to TCDD; the evidence on this outcome was deemed inadequate for drawing a conclusion about an association with maternal exposure to any of the COIs or with paternal exposure to any of the COIs other than TCDD. No changes in this category were made in Update 2000 or Update 2004. The Update 2006 committee removed brain cancer and several digestive cancers from this category because of a concern that the overall paucity of information on picloram and cacodylic acid made it inappropriate for those outcomes to remain in this category. This left the finding of evidence of no association between paternal exposure to TCDD and spontaneous abortion as the sole entry in this category.

Determining Increased Risk in Vietnam Veterans

The second part of the committee’s charge was to determine, to the extent permitted by available scientific data, the increased risk of disease among people exposed to herbicides or the contaminant TCDD during service in Vietnam. Previous reports pointed out that most of the many health studies of Vietnam veterans were hampered by relatively poor measures of exposure to herbicides or TCDD and by other methodologic problems. Most of the evidence on which the findings regarding associations are based, therefore, comes from studies of people exposed to TCDD or herbicides in occupational and environmental settings rather than from studies of Vietnam veterans. The committees that produced VAO and the updates found that the body of evidence was sufficient for reaching conclusions about statistical associations between herbicide exposures and health outcomes but that the lack of adequate data on Vietnam veterans themselves complicated the consideration of the second part of the charge.

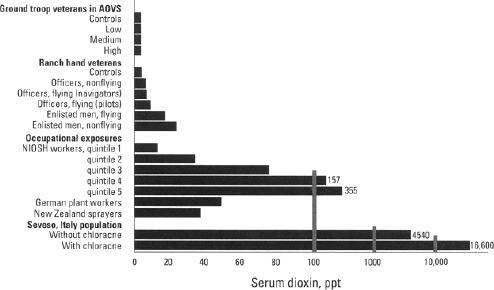

The evidence of herbicide exposure among the various groups studied suggests that although some had documented high exposures (such as participants in Operation Ranch Hand and Army Chemical Corps personnel), most Vietnam veterans had lower exposures to herbicides and TCDD than did the subjects of many occupational and environmental studies (see Figure 1-1 from Pirkle et al., 1995). However, individual veterans who had very high exposures to herbicides

SOURCE: Pirkle et al., 1995.

NOTE: AOVS = CDC Agent Orange Validation Study (CDC, 1989a); NIOSH, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

could have risks approaching those described in the occupational and environmental studies.

Estimating the magnitude of risk of each particular health outcome among herbicide-exposed Vietnam veterans requires quantitative information about the dose–time–response relationship for the health outcome in humans, information on the extent of herbicide exposure among Vietnam veterans, and estimates of individual exposure. The committees responsible for VAO and the updates have concluded that in general it is impossible to quantify the risk posed to veterans by their exposure to herbicides in Vietnam. Statements to that effect were made for each health outcome in VAO (IOM, 1994) and in every update through Update 2004. The committee responsible for Update 2006 chose to eliminate the repetitive restatements in favor of the following general conclusion: “At least for the present, it is not possible to derive quantitative estimates of the increase in risk of various adverse health effects that Vietnam veterans may have experienced in association with exposure to the herbicides sprayed in Vietnam.” The committees responsible for later updates and the current committee have all opted to retain the modification in the formatting of the health outcomes sections.

After decades of research, the challenge of estimating the magnitude of potential risk posed by exposure to the COIs remains intractable. The requisite information is still not available despite concerted efforts to use modeling to reconstruct likely exposure from records of troop movements and spraying missions (Stellman and Stellman, 2003, 2004; Stellman et al., 2003a,b), to extrapolate from agricultural models of drift associated with spraying (Ginevan et al., 2009a; Teske et al., 2002), to measure serum TCDD in individual veterans (Kang et al., 2006; Michalek et al., 1995), and to model the pharmacokinetics of TCDD clearance (Aylward et al., 2005a,b; Cheng et al., 2006; Emond et al., 2004, 2005, 2006). There is still uncertainty about the specific agents that may be responsible for a particular health effect. Even if one accepts an individual veteran’s serum TCDD concentration as the optimal surrogate for overall exposure to Agent Orange and the other herbicide mixtures sprayed in Vietnam, not only is it nontrivial to make this measurement but the hurdle of accounting for biologic clearance and extrapolating to the proper timeframe remains. Prior committees have thought it unlikely that additional information or more sophisticated methods would become available to permit any sort of quantitative assessment of Vietnam veterans’ increased risks of particular adverse health outcomes that are attributable to exposure to the chemicals associated with herbicide spraying in Vietnam.

The committee for this final update in the VAO series was pleased to have the opportunity to evaluate a set of papers (Yi, 2013; Yi and Ohrr, 2014; Yi et al., 2013a,b, 2014a,b) that reported the results of applying the Exposure Opportunity Index (EOI) model (Stellman and Stellman, 2003, 2004; Stellman et al., 2003a,b), which was developed with the encouragement of earlier VAO committees, to a large cohort of Korean veterans who served in the Vietnam War. The findings appear quite coherent, but this committee notes that there is no objective standard

by which estimates generated by the EOI model can be validated. This means that exposure estimation for the investigation of health outcomes in Vietnam veterans will remain a hurdle unlikely to be resolved in a fashion that will permit the conduct of epidemiology studies with greatly improved appraisals of association specifically linked to herbicide exposure.

Existence of a Plausible Biologic Mechanism

or Other Evidence of a Causal Relationship

Toxicology data form the basis of the committee’s response to the third part of its charge—to determine whether there is a plausible biologic mechanism or other evidence of a causal relationship between herbicide exposure and a health effect. A separate chapter summarizes toxicology findings on the chemicals of concern. In VAO and its updates before Update 2008, a considerable amount of detail was provided about individual newly published toxicology studies; the current committee concurs with the decision made by the committee for Update 2008 that it is more informative for the general reader to provide integrated toxicologic profiles for the COIs by interpreting the underlying experimental findings. In addition, when specific toxicologic findings pertinent to a particular health outcome are available, they are discussed in the chapter reviewing the epidemiologic literature on that condition. The current committee has continued the effort to refine this approach in order to make the chapter on toxicologic information more accessible to lay readers and to make more clear its relevance to epidemiologic findings.

In VAO and updates before Update 2006, this topic was discussed in the conclusions section for each health outcome after a statement of the committee’s judgment about the adequacy of the epidemiologic evidence of an association of that outcome with exposure to the COIs. As noted in Update 2006, the degree of biologic plausibility itself influences whether the committee perceives positive findings to be indicative of a pattern or the product of statistical fluctuations. To provide the reader with a more logical sequence, the committee responsible for Update 2006 placed the biologic-plausibility sections between the presentation of new epidemiologic evidence and the synthesis of all the evidence; this in turn led to the ultimate statement of the committee’s conclusion. The later committees have agreed with that change and have continued to arrange the sections in that fashion.

ORGANIZATION OF THIS REPORT

The remainder of this report is organized into 14 chapters. Chapter 2 briefly describes the considerations that guided the committee’s review and evaluation of the scientific evidence. Chapter 3 addresses exposure-assessment issues. Chapter

4 summarizes the toxicology data on the effects of 2,4-D, 2,4,5-T and its contaminant TCDD, cacodylic acid, and picloram; the data contribute to the consideration of the biologic plausibility of health effects in human populations. Chapter 5 characterizes the relevant new epidemiologic literature published during this update period, providing the study design, exposure measures, health outcomes reported, and population studied. Chapter 6 offers a cumulative overview of the study populations that have generated findings (in some instances presented in dozens of separate publications) reviewed in the VAO report series. In addition to showing where the new literature fits into this compendium of previous publications on Vietnam veterans, occupational cohorts, environmentally exposed groups, and case-control study populations, Chapter 6 includes a description and critical appraisal of the approaches used in the design, exposure assessment, and analysis in these studies.

The committee’s evaluation of the epidemiologic literature and its conclusions regarding the associations between exposures and the particular health outcomes that might be manifested long after exposure to the COIs are presented in the chapters that follow. In Update 2010, three short-term responses presumptively associated with herbicide exposure (early-onset peripheral neuropathy, chloracne, and PCT) were moved from the body of the report to Appendix B because they develop shortly after exposure and are unlikely to arise for the first time decades after the exposed people left Vietnam. A new feature adopted in Update 2012 was the placement of a summary of the finding for each health outcome at the beginning of the chapter.

Chapter 7, the first of the chapters evaluating epidemiologic evidence concerning particular health outcomes, addresses immunologic effects and discusses the reasons for what might be perceived as a discrepancy between a clear demonstration of immunotoxicity in animal studies and a paucity of epidemiologic studies with similar findings. Its placement in the report reflects the committee’s belief that immunologic changes may constitute an intermediate step in the generation of distinct clinical conditions, as discussed in subsequent chapters.

Chapter 8 discusses issues related to the possible overall carcinogenic potential of the COIs, particularly TCDD, and then assesses, in order of their codes in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), the available epidemiologic evidence on specific types of cancer, which are regarded as individual disease states that might be found to be service related.

In Update 2012, what had previously been one chapter on reproductive and developmental effects was partitioned into two chapters, and this report follows that pattern. The first of the two, Chapter 9, addresses reproductive problems that may have been manifested in the veterans themselves: reduced fertility, pregnancy loss, or gestational issues (low birth weight or preterm delivery). The second, Chapter 10, focuses on problems that might be manifested in veterans’ children at birth (traditionally defined as birth defects) or later in their lives

(childhood cancers, plus a broad spectrum of conditions for which impacts from parental exposures have been posited) or even in later generations.

Chapter 11 addresses neurologic disorders. Chapter 12 deals with a set of conditions related to cardiovascular and metabolic effects, which were gathered into a separate chapter by the committee for Update 2010 on the basis of their apparent interrelationship in the emerging medical phenomenon known as “metabolic syndrome.” Chapter 13 now contains the residual “other health outcomes” about which epidemiologic results related to the chemicals of interest have been encountered in the course of this series of VAO reports: respiratory disorders, gastrointestinal problems, kidney disease (new in this report), thyroid homeostasis and other endocrine disorders, eye problems, and bone conditions.

A summary of the committee’s findings and its research recommendations are presented in Chapter 14. In this last update mandated by PL 102-4 and PL 107-103, the committee also discusses how best to monitor the possibility of additional health outcomes associated with herbicide exposure. In the interest of minimizing unnecessary repetition, for the first time in this series of updates, the citations for all chapters have been merged into a single reference list that follows all the chapters.