2

Background

The central task of the committee was to carry out an epidemiologic analysis of potential associations between Project Shipboard Hazard and Defense (SHAD) test exposures and long-term health outcomes. An understanding of the background to the tests and the details of how they were carried out informed the committee’s approach to the study and provides context for the concerns and perspectives of the veterans who participated in these tests.

This chapter reviews the history of Project SHAD and efforts to reconstruct information about the tests and identify military service members who participated in them. It presents summary information about the tests and discusses a few in greater detail to illustrate some of the variation among them. It provides a brief review of studies of the health of SHAD veterans, including the design and findings of SHAD I, the previous Institute of Medicine (IOM) study of the long-term health effects of associated with participation in Project SHAD (IOM, 2007). Finally, this chapter describes the concerns of the veterans who were assigned to the ships and other units that participated in the tests.

PROJECT SHAD1

Origins and Termination

During the Cold War, the U.S. government was concerned not only about nuclear threats from the Soviet Union and China but also that the Soviet Union had programs to develop biological and chemical warfare agents and delivery systems. At the start of the Kennedy administration in 1961, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara requested a broad assessment of the military challenges facing the United States and military readiness to meet these challenges. Among the approximately 150 numbered projects that resulted, Project 112 addressed biological and chemical warfare capabilities and defense (DoD, 2003c).

______________

1 The description in this report of the history of Project SHAD and the efforts by DoD since 2000 to provide documentation of test activities draws extensively from two unpublished documents. One document is a report submitted to Congress in 2003 by Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs William Winkenwerder. The other source is a master’s thesis prepared by Dee Morris, who led DoD work to assemble information for the Project 112 and Project SHAD fact sheets and to compile additional information about the tests for the SHAD I study by the Institute of Medicine.

In 1962, when Project 112 began, the effects of varying climates and terrain on potential biological and chemical weapons were not known, nor was the feasibility and effectiveness of decontamination in varying settings and environments. The classified testing conducted for Project 112 was designed to improve knowledge in these areas, and some of the tests—those now referred to as the Project SHAD component of Project 112—focused on ships and the marine environment (Morris, 2004).

The testing program was managed by the Deseret Test Center (DTC), which was established by the U.S. Army in June 1962 at Fort Douglas, Utah. DTC was funded and staffed by all of the military services. The services submitted testing requirements annually, and test objectives and priorities were determined at joint planning conferences by service and joint and combatant command representatives (DoD, 2003c; GAO, 2004). Initial plans for Project 112 called for tests to take place “in the Pacific Ocean or on land in Alaska, Hawaii, and the then-Panama Canal Zone” (DoD, 2003c, unnumbered p. 5). Ultimately, some additional locations were also used. It is evident from the test plans and descriptions that the tests were intended to evaluate operational characteristics of ships and protective and dissemination equipment as well as the behavior of the test agents in marine environments; these tests were clearly not concerned with assessing health impacts. A modern analogy is the testing for the integrity of important buildings in the face of Homeland Security concerns. Tests to evaluate the effects of the agents on human health would have required different designs.

According to the Department of Defense (DoD), 134 classified tests were planned for land or sea, involving open-air use of various combinations of active agents (both chemical and biological), simulants, tracers, and decontaminants (DoD, 2003c). Of the planned Project 112 tests, 50 were completed and 84 were cancelled (DoD, 2015). The completed tests included 212 that involved Navy vessels and that DoD designated as SHAD tests (DoD, 2014) in its 2000-2003 review and declassification of materials related to the testing program. Each SHAD test was conducted over a period of weeks or months and included several “trials,” each of which was typically conducted on a separate day. Table 2-1 provides a list of the designations and features of the SHAD tests. The first SHAD test began in January of 1963, and the final SHAD test using active agents or simulants was conducted in 1969. Some Project 112 testing continued in the period 1970-1974, all of it conducted at Dugway Proving Ground, Utah.

DoD has cited several developments as contributing to the termination of Project 112 and Project SHAD (DoD, 2003c). In November 1969, President Nixon announced a moratorium on biological weapons testing and that research on biological weapons should focus on defense, including “on techniques of immunization, and on measures of controlling and preventing the spread of disease” (Nixon, 1969).3 Funding for DTC was “severely curtailed” by mid-1971, and the center was closed in 1973 (DoD, 2003c, unnumbered p. 7). Upon its closure, most of its records were transferred to Dugway Proving Ground (Morris, 2004, p. 6).

______________

2 Of 21 tests designated as SHAD tests by DoD, 20 involved potential exposure to agents, simulants, tracers, or decontaminants. Test DTC 70-C, which took place in 1972 and 1973 (DoD, 2003b), involved only passive air sampling to characterize naturally occurring airborne particles in the marine atmosphere.

3 Also in November 1969, PL 91-121 (50 U.S.C. 1512) required a determination by the Secretary of Defense that transport or testing of any chemical or biological warfare agents in the United States was in the interest of national security and that any precautionary measures recommended by the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare first be implemented. In 1970, the Clean Air Act (PL 91-604) authorized the development of federal and state regulations to limit the release of harmful substances into the air (see EPA, 2014).

TABLE 2-1 Features of Shipboard Hazard and Defense (SHAD) Tests, 1963 to 1969

| Test | Date | No. of Trials | Location | Participating Units (# trials) | Agent or Simulant Useda | Protective Gear/ Decontamination | Purpose |

| Eager Belle I (Test 63-1) | Jan, Mar 1963 | 19 | Pacific Ocean, west of Oahu, Hawaii | USS George Eastman | Bacillus globigii (BG) | Test effectiveness of face masks and protective devices for ship | |

| Eager Belle II (Test 63-1) | Feb, Mar, Jun 1963 | 14 | Pacific Ocean, west of Oahu | USS George Eastman (11) USS Carpenter (1) USS Navarro (1) USS Tioga County (1) USMC Medium Helicopter Squadron 161 | Bacillus globigii (BG) | Obtain information (1) on models for travel of biological aerosols; (2) on weapon system performance; (3) for design of future tests | |

| Autumn Gold (Test 63-2) | May 1963 | 9 | 60 miles west-southwest of Oahu | USS Carpenter (9) USS Hoel (7) USS Navarro (9) USS Tioga County (9) Marine Air Group 13 | Bacillus globigii (BG) | M17 and Mark V masks | Test aerosol penetration of ships under three readiness conditions; estimate magnitude and persistence of dispersed agent after washdown; evaluate masks |

| Errand Boy (Test 64-1) | Sep 1963 | 8 | East Loch, Pearl Harbor, Hawaii | USS George Eastman | Bacillus globigii (BG) | Betapropiolactone (BPL) | Test decontamination procedures for external surfaces |

| Flower Drum I (Test 64-2) | Feb-Apr, Aug-Sept 1964 | 31 | Pacific Ocean, off coast of Hawaii | USS George Eastman | Sarin (GB) Methyl acetoacetate (MAA) Sulfur dioxide (SO2) | M5 Protective Ensemble for disseminator crew Others wore MK5, M7A1 and M17 masks inside the Safety Citadel | Find simulant for GB, assess penetration of vapor of GB and simulant |

| Shady Grove (Test 64-4) | May 1964; Jan-Apr 1965 | 25 | Pacific Ocean | 5 Army tugs Marine Air Group 13 USN Patrol Squadrons 4 and 6 USN AEWBARONPAC | Coxiella burnetii (OU) Pasteurella tularensis (UL) Bacillus globigii (BG) Zinc cadmium sulfide (tracer) | Determine infectivity, viability, and atmospheric diffusion of UL; assess capability of weapon system; evaluate procedures for tests with pathogenic agents | |

| Test | Date | No. of Trials | Location | Participating Units (# trials) | Agent or Simulant Useda | Protective Gear/ Decontamination | Purpose |

| Flower Drum II (Test 64-2) | Nov-Dec 1964 | 10 | Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Oahu | USN tug ATF 105 Unmanned USN barge YFN-811 | VX Phosphorous 32 Bis (2 ethyl-hexyl) hydrogen | Shipboard water washdown | Test effectiveness of shipboard water washdown against VX; obtain operational experience for planning test designated Fearless Johnny |

| Copper Head (Test 65-1) | Jan-Feb 1965 | 10 | Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada | USS Power | Bacillus globigii (BG) Zinc cadmium sulfide (FP) | Betapropiolactone (BPL) | Test in a frigid marine environment: extent of aerosol penetration into an operational ship under three conditions of readiness; compare travel of a biological cloud with diffusion model predictions; effectiveness of BPL; operational feasibility of deck washdown system; performance of spray tank system |

| High Low (Test 65-13) | Jan-Feb 1965 | 33 | Pacific Ocean, off the coast of San Diego | USS Berkeley USS Fechteler USS Okanogan USS Wexford County | Methyl acetoacetate (MAA) | Protective masks | Using a simulant, investigate the potential penetration of a cloud of sarin into four types of naval ships |

| Big Tom (Test 65-6) | Apr-Jun 1965 | 19 | Off the coast of Oahu, and on Oahu | USS Carbonero | Bacillus globigii (BG) Fluorescent particles of zinc cadmium sulfide (tracers) | Betapropiolactone (BPL) (USS Carbonero) | Evaluate the feasibility of a biological attack on an island complex; evaluate doctrine and tactics for such an attack |

| Test | Date | No. of Trials | Location | Participating Units (# trials) | Agent or Simulant Useda | Protective Gear/ Decontamination | Purpose |

| Magic Sword (Test 65-4) | May 1965 | 8 | Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Baker Island (and on Baker Island)b | USS George Eastman | Uninfected mosquitoes | Nonpersistent insecticide Heat (DDT on Baker Island) | Study the (1) feasibility of offshore release of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, (2) mosquito biting habits, (3) trap technology, and (4) delivery of mosquitoes to remote sites |

| Fearless Johnny (Test 65-17) | Aug-Sep 1965 | 17 | Pacific Ocean, southwest of Oahu | USS George Eastman 2 light tugsc USN Patrol Squadron 6 (Naval aviation unit) | VX (3 trials) Diethylphthalate (DEP) with dye (14 trials) | Water washdown system | Evaluate contamination (external, internal) from aerial dissemination of nerve agent simulant; test effectiveness of decontamination process; assess impact of gross VX contamination |

| Purple Sage (Test 66-5) | Jan-Feb 1966 | 21 | Pacific Ocean, off the coast of San Diego | USS Herbert J. Thomas | Methyl acetoacetate (MAA) | Protective mask (MK5 or M17) | Evaluate the effectiveness of the Shipboard Toxicological Operational Protection System (STOPS) against gaseous chemical warfare agents; evaluate the impact of protective masks on crew efficiency |

| Scarlet Sage (Test 66-6) | Feb-Mar 1966 | 19 | Pacific Ocean, off the coast of San Diego | USS Herbert J. Thomas AVR boat North Island | Bacillus globigii (BG) | Water washdown | Evaluate the effectiveness of the Shipboard Toxicological Operational Protective System (STOPS) against a biological aerosol; determine level of contamination and effectiveness of decontamination system; evaluate nasal-pharyngeal wash for detecting inhalation of biological aerosol |

| Test | Date | No. of Trials | Location | Participating Units (# trials) | Agent or Simulant Useda | Protective Gear/ Decontamination | Purpose |

| Half Note (Test 66-13) | Aug-Sep 1966 | ≥27 | Pacific Ocean, south-southwest of Oahu | USS George Eastman 5 Army tugs USS Carbonero (BG release) | Escherichia coli (EC) Serratia marcescens (SM) Bacillus globigii (BG) Calcofluor (tracers) Zinc cadmium sulfide | Calcium hypochlorite in water (USS Carbonero) | Determine decay rates of nonpathogenic organisms in marine environment Assess contamination hazards for USS Carbonero |

| Folded Arrow (Test 68-71) | Apr-May 1968 | 11 | Pacific Ocean, south-southwest of Oahu and off the coast of Oahu | 5 Army tugs USS Carbonero (disseminator) | Bacillus globigii (BG) | Betapropiolactone (BPL) Calcium hypochlorite | Study over-ocean downwind travel of biological aerosols; demonstrate capability of submarine weapon system for biological attack against islands and ports; Evaluate contamination hazard to submarine crew |

| Test 69-31 | Aug-Sep 1968 | 16 | Off the coast of San Diego | USS Herbert J. Thomas | Methyl acetoacetate (MAA) Bacillus globigii (BG) | Evaluate the continued effectiveness of STOPS after operational deployment | |

| Speckled Start (Test 68-50) | Sep-Oct 1968 | 21 | Pacific Ocean, Eniwetok Atoll | 5 Army tugs USAF 4533rd Tactical Test Squadron, 33rd Tactical Fighter Wing | Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB) Bacillus globigii (BG, dry) Uranine dye | Determine the potential casualty area and associated casualty levels for aerosols dispersed by the F-4/AB45Y-4/PG2 weapon system | |

| Test 69-32 | Apr-Jun 1969 | 27 | Pacific Ocean, southwest of Hawaii | 5 Army tugs USN A-4C aircraft from VC-1 squadron | Escherichia coli (EC) (13 trials) Serratia marcescens (SM) (14 trials) Bacillus globigii (BG) Calcofluor (tracer) | Evaluate the effect of sunlight on the viability of biological aerosols disseminated in a temperate environment at about sunrise and sunset | |

| Test | Date | No. of Trials | Location | Participating Units (# trials) | Agent or Simulant Useda | Protective Gear/ Decontamination | Purpose |

| Test 69-10 | May 1969 | ≥4 | Vieques Island, Puerto Rico | USS Fort Snelling (LSD-30) USMC Landing Force Carib 1-69/BLT 1/8 (2nd Marine Division) USMC VMA-324, MAG-32 | Trioctyl phosphate (TOF) (also known as tri(2-ethylhexyl) phosphate [TEHP]) | Determine the operational effects during an amphibious landing of a persistent chemical agent spray attack on troops wearing protective clothing and on contamination of troops, ships, and equipment | |

NOTES: The USS Granville S. Hall was present during the following SHAD tests as an escort ship or to provide laboratory facilities for analysis of samples collected during SHAD tests: Eager Belle II, Autumn Gold, Flower Drum I, Shady Grove, Big Tom, Fearless Johnny, Folded Arrow, Half Note, Speckled Start, and Test 69-32. It did not serve as a test ship during SHAD tests. Test 70-C did not involve the release of a test agent or use of tracers or decontaminants. It is not included here and was not included in any of the analyses discussed in this report. AEWBARONPAC = Airborne Early Warning Barrier Squadron Pacific; MAG = Marine Air Group; USAF = United States Air Force; USMC = United States Marine Corps; USN = United States Navy

a Active agents are listed first, followed by simulants and tracers.

b The portion of the test conducted on Baker Island has not been included in any of the analyses discussed in this report.

c Two light tugs were reported to serve as couriers (not test vessels) during Fearless Johnny.

Reconstruction of Information About Project SHAD

During the 1990s, some veterans raised concerns to the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) that they had health problems that were the result of exposures during the Project 112 and Project SHAD tests. Because the testing programs were classified, service members reported that they were forbidden to discuss their participation the tests (e.g., Personal communication, G. Arnold, SHAD veteran, USS Navarro, February 23, 2012),4 and VA had little information about the tests. Congressional inquiries on behalf of SHAD veterans received varying responses from the Department of the Army, which serves as DoD’s executive agent for chemical and biological testing. At least one response from the Department of the Army noted the existence of some of the tests and that veterans who felt they might have service-connected health problems could submit claims to VA, and the Army would respond to VA requests for information (Beard, 1996).

In May 2000, a series of investigative television news reports brought public attention to the SHAD testing.5 In August 2000, the acting secretary of VA, Hershel Gober, sent a request to DoD for information about Project SHAD testing, including lists of the names and dates of tests, the agents used, and the military units and individuals who were participants in the tests (Gober, 2000). DoD’s efforts to prepare this material required locating information contained primarily in paper records of classified activities that had occurred 30 to 40 years earlier. By October 2003, DoD had produced a list of the Project 112 and Project SHAD tests that are known to have been planned, and it prepared unclassified fact sheets about each test that was conducted (see DoD, 2015).

Within DoD, responsibility to assemble the information requested by VA was eventually assigned to the Office of the Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for Gulf War Illnesses, Medical Readiness, and Military Deployments.6 Their investigation into SHAD testing included a review of files by the Army, requests for additional information from other military commands or units likely to have received copies of the reports, and interviews with people with information about the SHAD testing program. It also resulted in interagency meetings that included representatives of VA, DoD, and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). An unpublished paper by the DoD staff member assigned to lead this work provides insight into the challenges of locating records of the SHAD test program and reconstructing the program’s history (Morris, 2004).

The first phase of the investigation focused on gathering information about the SHAD tests designated Autumn Gold, Shady Grove, and Copper Head. The first two of these tests were identified by the acting VA Secretary Gober and by Congressman Mike Thompson (California) as being of interest, and the Army had reported in its initial response to VA that it had

______________

4 In 2011, DoD issued a memorandum that released veterans from any nondisclosure obligations (including any “secrecy oaths”) related to their potential exposure to chemical or biological agents (DoD, 2011). This release allows for discussions of health concerns, but it does not authorize release of technical or operational information. No written secrecy oaths related to the Project SHAD tests were located by DoD during its investigation into the Project 112 testing (Personal communication, Michael E. Kilpatrick, Force Health Protection and Readiness Programs, Department of Defense, to the IOM Committee on Shipboard Hazard and Defense II, January 19, 2012).

5 The series of reports were presented by Vince Gonzales on CBS News (Murphy, 2003), based on investigations by Eric Longabardi.

6 This organization is now known as the Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Readiness Policy and Oversight.

unclassified information on Copper Head (Morris, 2004). The second phase of the investigation was to cover the remaining SHAD tests as time and resources permitted, with priority given to any tests named in claims that veterans had filed with VA (Morris, 2004). The investigation into SHAD tests also led to the identification and documentation of land-based tests that were part of the broader Project 112 testing program.

Obtaining information about SHAD tests was challenging because the term “Project SHAD” was not in wide use (e.g., in test plans or reports) at the time the tests were conducted and so was not a useful search term in databases (Morris, 2004, p. 8). The investigation began with a search by the staff at Dugway Proving Ground of classified technical holdings there. The Dugway staff identified 38 classified documents relevant to Project SHAD, and copies were sent to the investigators, who reviewed them for “medically relevant information” (described as “i.e. where, when, to what vessel/unit”). Later in the process, the SHAD investigators made a further on-site search of the materials held at Dugway, which resulted in finding additional documents as well as films of some of the tests.7 Some documents related to the tests had originally been distributed beyond DTC and were located by the investigators in files at the U.S. Army Edgewood Chemical Biological Center (Edgewood, Maryland) and the Naval Surface Warfare Center (Dahlgren, Virginia). Documents were also identified and obtained through the catalogue and collection of the Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC). In addition, the investigators also conferred with J. Clifton Spendlove, the technical director for the tests, about the testing program and the documents and films found.

The SHAD investigators requested declassification of documents by the appropriate originating agencies in the Army and the Navy (Morris, 2004), but the volume of material (more than 28,000 pages) could not be reviewed in a timely manner by those agencies. Plans to seek declassification of entire documents were abandoned, and as of 2004, approximately 400 pages had been declassified after 14 separate requests (Morris, 2004).

Investigators used clues in the classified documents to guide them to unclassified operational and personnel records at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in College Park, Maryland. VA agreed to accept a record of an individual’s assignment to a participating unit or vessel at the time of a SHAD test as sufficient evidence of participation in the test. To compile rosters of personnel qualifying as SHAD test participants, DoD investigators examined quarterly personnel summaries for the periods immediately before and after SHAD test dates (Morris, 2004). Personnel who were named on both summaries were presumed to have been test participants. If a person’s name appeared on only one summary, daily muster rolls had to be checked to clarify whether he should be considered a test participant. As of 2003, DoD had identified approximately 5,900 individuals who were assigned to ships or other military units that participated in SHAD or other Project 112 tests (GAO, 2004).

A 2004 review by the General Accounting Office (GAO) described DoD’s processes for finding materials to identify Project 112 tests as satisfactory: “It appears that DOD used a reasonable approach for identifying the locations of records and source documents, particularly since some of the Project 112 tests were conducted more than 40 years ago and the record-keeping systems were much less sophisticated than today’s” (GAO, 2004, p. 11). The GAO review included examination of materials that DoD investigators had used (including selective examination of materials stored at Dugway Proving Ground) and interviews with staff members at DoD and former officials and managers from DTC. However, GAO (2004, 2008) also

______________

7 Morris (2004) reports that some of the films were transferred to other formats but that sound tracks were lost. The committee requested copies of this video material, but DoD declined to publicly release it.

concluded that further DoD effort would be warranted to identify additional military and civilian personnel who may have been participants in SHAD or other Project 112 tests.8

Some of the SHAD veterans who presented written or oral statements to this committee (e.g., February 2012 IOM meeting; Personal communication, J. Alderson, U.S. Navy Reserve (Ret.), January 22, 2013) expressed views skeptical of the thoroughness of the DoD investigation and that additional information about the tests is available. The committee’s understanding is that additional, and potentially relevant, material on SHAD tests exists and remains classified. The IOM committee requested declassification of 21 additional elements from at least nine documents from DoD in August 2012. In January 2014, an additional request was made for release of multiple films made of Project SHAD tests. None of the requested materials were cleared for public release as of this writing.

THE SHAD TESTS

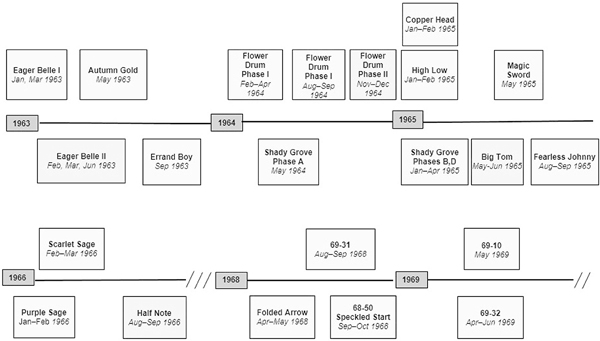

Figure 2-1 shows the timing of tests that DoD has identified as being part of Project SHAD. Table 2-1 includes information about when and where the tests were conducted, the military units that participated, and the substances used. Additional description of each of the tests is provided in the annex to this chapter. Two of the tests have been excluded from most of the subsequent discussion and analysis in this report because no participants in the tests have been identified (Flower Drum II), or because the test did not involve the release of any substances (DTC 70-C).

As Table 2-1 illustrates, the SHAD tests had varying goals and test conditions. Some tests used only simulants, and others used active biological or chemical agents. The tests also differed in that some were carried out with “regular” Navy ships and crews, while others used specially designed test or sampling vessels with specially trained personnel. Among the vessels used in the SHAD tests were five light tugboats previously under Army command that were transferred to the Navy.

The tests using active biological agents involved selected personnel designated as Project SHAD Technical Staff (PSTS), who had security clearances and special training. PSTS manned the light tugs and the laboratory on the USS Granville S. Hall where the biological samples were evaluated. The light tugs had been modified to include a small laboratory and provide a positive pressure environment to limit interior exposure to test pathogens. Manned tests involving active chemical agents were carried out using the USS George Eastman, which had been modified in ways specifically designed to provide protection from chemical agents. Regular Navy vessels and crews were involved only in tests using simulants, not active chemical or biological agents.

As noted, a given test usually included several “trials” that were conducted over the course of days or weeks. Within a test, individual trials may have used different ships, test substances, or test conditions. Autumn Gold, for example, was conducted using four regular Navy ships and the simulant Bacillus globigii (BG) in nine different trials.

______________

8 In September 2011, a contract was awarded to Battelle by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs/Chemical and Biological Defense to continue efforts of the Chemical and Biological Archive Information Management System and the U.S. Chemical and Biological Tests Repository to identify and collect Chemical and Biological Defense archival information as well as search for personnel potentially exposed to chemical agents, biological agents, or simulants while involved in tests and other ancillary events (McKim, 2013).

The SHAD tests have in common that they seem to have been designed to gather operational information about the penetration of test substances into the ships, or the behavior of these substances in the specific marine environments in which they were tested. They do not have characteristics of tests carried out to evaluate the effects of the test agents on humans; such tests would presumably have included some health assessment of the study participants. In a few tests, however, samples indicating human exposure, such as gargle samples, or chemical dosimeters from clothing were collected from service members who were exposed to the test agents to evaluate personal protective equipment (Autumn Gold, DTC 69-10, Copper Head).

Three of the tests are described further here to illustrate some of the varied features of SHAD testing. A full description of each of the tests is included as an annex to this chapter.

Autumn Gold

The Autumn Gold test (Test 63-2) was carried out in May 1963 in open sea in the Pacific Ocean approximately 60 miles west-southwest of Oahu, Hawaii. Its purpose was “to determine the degree of penetration of representative fleet ships, operating under three different material readiness conditions [ship ventilation characteristics,], by a simulant biological aerosol released from an operational weapon system” (DTC, 1964, p. iii). BG was the simulant used for this purpose. Another objective was “to estimate the magnitude and persistency [sic] of simulant biological aerosols retained after conducting air wash and hose down procedures” (DTC, 1964, p. 3). The test also provided information on the performance under the test conditions of a bacteria detector and counter and of the M17 and Mark V protective masks (DoD, 2003a).

A material readiness condition characterizes the status of ventilation settings and system access or closure on a ship. Autumn Gold was conducted in three phases of three trials each, to test the effect of material readiness conditions of Yoke, Zebra, and Zebra Circle William (DoD, 2004).9 The participating ships were the USS Navarro, the USS Tioga County, the USS Carpenter, and the USS Hoel. In each trial, two A4B jet aircraft, each equipped with two modified Aero 14B spray tanks, disseminated BG along a single release line. For the purposes of assessing exposures for this IOM study, each release line for each trial was considered a potential exposure.

According to the final report on this test:

Personnel on each ship were briefed on procedures for pretrial exercises and the need was stressed for attaining the three material readiness conditions during the pretrial training exercises and subsequent trials. Ship personnel conducted these exercises and inspections prior to the AUTUMN GOLD (U) trials to determine each ship’s capability to fully attain these readiness conditions under its present condition…. Navy personnel from each ship were assigned to operate the various sampling equipment on the ship. These men were trained during the week prior to the first trial. (DTC, 1964, p. 7)

The test plan10 describes procedures to test for potential for leakage of the M17 and Mark V protective masks under operational conditions using “32 test subjects (eight per ship, four at

______________

9 Yoke refers to routine ventilation settings in non-battle conditions. Zebra is for fire or flood control and intended to minimize water entry. Under Zebra Circle William, Circle William fittings were also closed and all ventilation fans were secured (DTC, 1965a).

10 A test plan was a document prepared to describe planned aspects of the study in detail. It is distinct from a final report, which is intended to describe what actually took place during the test.

each of two stations per ship) … positioned at two above-deck sampling sites. Sixteen test subjects will don the M17 protective mask and 16 subjects will don the Mark V protective mask at function time and continue wearing the masks until Z+35 minutes” (DTC, 1963a, p. 74). The plan also states that those not wearing the masks would provide gargle samples before and after the test (DTC, 1963a).

Roles for a test site safety officer and medical liaison are outlined in the test plan, with the comment that “the major objective of the medical support program is to maintain the health and welfare of both military and civilian personnel while on the test site and during test operation” (DTC, 1963b, p. 80).

Shady Grove

Most of the Shady Grove test (Test 64-4) took place in the Pacific Ocean and included a total of 25 ship-based trials that were conducted as Phases A, B, and D. Phase A was conducted in May 1964 and phases B and D during January-April 1965. (Phase C was conducted on land and is not discussed further.) Some of the Shady Grove trials used BG as a biological tracer, but other trials used the pathogenic agents Coxiella burnetii (referred to in the SHAD documents as OU), which causes Q fever, and Pasteurella tularensis (referred to as UL), which causes tularemia. Fluorescent particles (FP) of zinc cadmium sulfide were used as a tracer in all of the trials.

The stated objectives of the Shady Grove test were

- To evaluate infectivity of agent UL [Pasteurella tularensis] aerosols over effective downwind distances, utilizing an elevated line source from an operational weapon in a marine environment. 2) To determine the viability decay of UL over effective downwind distances. 3) To characterize atmospheric diffusion in a marine environment. 4) To assess the operational capability of the weapon system. (DTC, 1965c, p. 5)

The test ships for Shady Grove were five light tugs (LTs), which carried samplers, and for some tests, animals in cages. Agents were released by a spray tank on a jet aircraft or by a disseminator mounted on one of the tugs. The USS Granville S. Hall served as the laboratory support ship.

Phase A was a meteorological study that included six aerial and two surface releases of BG and FP (DoD, 2004; DTC, 1965c). Phase B, in February and March 1965, included eight aerial releases of UL and BG together and one aerial release of UL only. There were also four surface releases of both UL and BG from a tug-mounted disseminator (DTC, 1965c). In the four Phase D trials, which took place between March 22 and April 3, 1965, A4C jets simultaneously disseminated BG from one tank and OU from another tank along several release lines (one aircraft per line). BG and FP were used as tracers (DTC, 1965c).

The final report indicates an awareness of safety issues and that the test was considered successful from that and other perspectives. It states that the absence of any “industrial type accidents or agent exposures” indicated an “exceptional job done in the training and execution of a test program of this magnitude” and “confirmed the feasibility of using operational combat units, with a minimum amount of personnel training and experience, to deliver biological weapons on targets from remote bases throughout the world” (DTC, 1965c).

Flower Drum II

Although no personnel could be identified as participants in the Flower Drum II test, it is briefly described here as an example of a test that used an active chemical warfare agent. The test was carried out in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Hawaii in November and December 1964, and included 10 trials. It was conducted to test water washdown to protect against or decontaminate after encountering an aerial spray of VX and to aid in planning a future SHAD test (DTC, 1965a). The platform for the test was the US Navy covered lighter (barge) YFN-811, which was towed by the US Navy tug ATF 105.

A spray device on the barge disseminated the test agent, which was a dyed liquid containing approximately 90 percent VX (by weight). Three conditions of water washdown were tested: (1) operating the washdown system before, during and after dissemination; (2) using the washdown immediately before and after dissemination; and (3) conducting a washdown only after dissemination was complete (DTC, 1965b).

The information available to the committee does not indicate that any people were aboard the barge during the test. Because no deck logs were found for either vessel, no veterans who may have participated in the test could be identified and included in the analysis for either the SHAD I study or the current study.

PREVIOUS STUDIES OF SHAD VETERANS

Two previous studies have investigated the health outcomes and health status of SHAD veterans. One study (Kang and Bullman, 2009) was conducted by VA personnel. The other was the previous study conducted at the IOM (2007). Both studies are briefly reviewed here.

VA Study of SHAD Veterans

Kang and Bullman (2009) carried out a study of mortality in the Navy SHAD veteran population. In their study, 4,927 SHAD study participants and a comparison veteran population were followed to date of death or December 31, 2004, whichever was earlier. The comparison population of veterans who did not participate in SHAD tests was a stratified random sample of 10,927 men drawn from a group of 164,277 male Vietnam-era veterans who served in the Navy between 1962 and 1973 (the time frame for the SHAD tests). The control subjects were selected using birth-year strata to provide a roughly 2-to-1 match with the SHAD veterans. Within the population of SHAD veterans, the researchers also compared the veterans who were exposed to active biological or chemical agents with those who were only exposed to simulants or tracers. The study found a statistically significant increased risk of overall mortality among SHAD veterans (an all-cause adjusted rate ratio [ARR] of 1.10, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01-1.97), with the excess mortality due primarily to heart disease (heart disease ARR 1.39, 95% CI 1.18-1.64). The increased risk was observed only in those SHAD veterans who were exposed to simulants, not in those potentially exposed to active chemical or biological agents. No other excess in cause-specific mortality was observed among SHAD veterans.

The IOM’s Previous Study of SHAD Veterans

In 2002, the IOM was asked to conduct a study to assess whether SHAD veterans might be experiencing adverse health conditions that could be associated with their participation in

Project SHAD. The IOM study chose a different strategy for selection of a comparison group for the study. Completed in 2007, the IOM’s SHAD I study compared the morbidity and mortality experience of SHAD veterans with that of a population of crew members of ships selected to match the ships that had participated in each SHAD test.11 This approach to the selection of a comparison population was used to attempt to ensure that members of the study population had service at sea (or in a similar Marine unit) at a similar time and in a similar geographic area, making inclusion in the SHAD tests a principal point of difference.

The IOM researchers assembled a roster of 5,867 Project SHAD veterans (test participants) and a comparison population of 6,757 Navy and Marine Corps personnel (controls) (IOM, 2007). Mortality data (including cause of death after 1979) were obtained from VA and the files of the National Death Index. Of the nearly 12,500 Navy and Marine Corps study subjects, approximately 9,600 were assumed to be alive as of December 31, 2004 (i.e., there was no evidence of death from available records sources).

The surviving participants and controls who could be located were asked to complete a health survey by mail or telephone. The survey included general demographic information and questions about smoking, weight, and alcohol use in order to have information about important influences on health status. It included portions of validated tests of physical symptoms and well-being in the form of the physical and mental health status components of the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36). It also included a standard list of medical conditions and symptoms for self-report, and a scale for assessing neurological problems and cognitive difficulties. Veterans of SHAD testing were asked additional questions about any symptoms experienced during the tests, use of protective gear during the tests, and experience with decontamination. Also included were several questions from a survey that SHAD veterans had designed and circulated as health concerns were first coming to light. Mail questionnaire or telephone interview responses were received from 61 percent of Project SHAD participants and 47 percent of controls.

The study included analyses of mortality and morbidity. Both standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) and proportional hazards modeling were used to analyze mortality. The covariates included in the analyses were participant status, SHAD participant exposure group, age, race, branch of service, pay grade, rank, length of service, vital status, date of death, and cause of death. The primary health outcome for the morbidity analysis was the score on the SF-36 assessment of general health. Also used were scores on two subscales of the SF-36: for the physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS). Other outcome variables derived from the health survey included a history of medical conditions, present symptoms, and hospitalizations after completion of military service.

Many of the analyses grouped Project SHAD participants into four broad exposure categories to evaluate whether health outcomes differed by specific patterns of exposure. Group A, with roughly 3,400 participants, was exposed only to BG or methylacetoacetate (MAA). In group B were the roughly 900 participants exposed to trioctyl phosphate (TOF) in Test 69-10. Group C included the approximately 750 participants who were potentially exposed to active chemical or biological agents, with or without possible additional exposure to simulants. Group D—870 participants—included the men who did not meet the criteria for the other three categories. Their exposures may have included BG or MAA in combination with other simulants or tracers or decontaminants; none of the men in Group D were exposed to active agents or TOF.

The study found no difference in all-cause mortality between Project SHAD participants and controls, although participants had a statistically significantly higher risk of death due to

______________

11 The selection of the ships for the comparison population is described in detail in Chapter 3.

heart disease (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.20, 95% CI, 1.03-1.39). The lack of data on cardiovascular risk factors or any explanation as to the biological plausibility of the association made the heart disease results difficult to interpret. Participants were also found to have reported statistically significantly worse health than controls as measured by the PCS and the MCS scores on the SF-36 portion of the questionnaire, but no consistent, specific, clinically significant patterns of ill health were found. The group with potential exposure to active chemical or biological agents had the most positive SF-36 health score among the four exposure groups. There were small but statistically significant increases in self-reported memory and attention problems in three of the exposure groups and in somatization scores for all participants. The full group of Project SHAD participants reported higher levels of neurodegenerative medical conditions compared with the control group, but most of these conditions were of an unspecified nature. Participants also reported nearly uniformly higher rates of various symptoms. However, higher rates of a symptom without an apparent medical basis (earlobe pain) suggested the possibility of reporting bias. The SHAD participants and controls had no significant differences in self-reported hospitalizations. Although the participants in one of the exposure groups reported a higher rate of birth defects than controls, this statistically significant difference was attributed to an unusually low rate of birth defects among the control group rather than to a higher rate among participants.12

While the SHAD I study found no clear evidence of specific health effects associated with participation in Project SHAD, the authors noted that the results do not constitute clear evidence of a lack of health effects. Some of the exposure groups were moderate in size, and the lack of specific a priori hypotheses of health effects was a limitation. If there were, for example, very specific but relatively infrequent effects on a particular organ system, the study’s broad groupings of health outcomes might have obscured such a specific effect.

Supplemental SHAD I Analyses

In February 2008 Congressmen Mike Thompson and Dennis Rehberg, who had received a briefing on the SHAD I study, directed five follow-up questions to the IOM. These questions requested additional information or clarification on the personnel who were included or excluded in the analysis, the availability of information on health outcomes for some SHAD participants, the potential impact of duty assignments on exposures of SHAD participants, and characterizations of the SHAD tests. In August 2008, IOM staff responded to these questions with comments and supplemental analyses (IOM, 2008).

The analysis included crews of the light tugs (104 men) for only one test (Shady Grove) because rosters for tug crews during other tests could not be located by DoD or through independent efforts by the IOM staff. No other means was found to identify crewmembers from these vessels. Conversely, the congressional questions also reflected concern that the crews of the USS Granville S. Hall and the USS George Eastman had less exposure than other SHAD participants and that their inclusion in the analysis could have obscured associations with adverse health outcomes. Supplemental analyses that separated the crews of these two ships found that all-cause mortality and self-reported physical health of the other SHAD participants was “essentially the same as the published results of analyses that included these personnel” (IOM,

______________

12 The self-reported rate of birth defects among group D participants was similar to the rate in the other participant groups; whereas, the self-reported rate among the controls for group D was markedly lower (IOM, 2007).

2008). There were, however, indications of higher mortality and poorer health status among the crew of the USS George Eastman when they were analyzed separately (IOM, 2008).

The supplemental report also reviewed the SHAD I efforts to identify all deaths among SHAD veterans and the cause of death for all deaths from 1979 through 2004. Determining causes of the 357 deaths that occurred before 1979 was not considered feasible during the SHAD I study, but obtaining as much of this information as possible was a specific priority for the SHAD II study. The lack of explicit information on crew members’ tasks or locations during tests and the IOM’s efforts to solicit information about the tests from SHAD veterans were both reiterated in the supplemental report. As has been noted, these concerns were a motivation in the SHAD II study to specifically develop new ways to incorporate information about likely variations in exposure in the analysis.

CONCERNS EXPRESSED BY SHAD VETERANS

An express element of the legislation that requested the IOM’s SHAD II study was that a public workshop be organized to ensure veteran input to inform the conduct of the study. The IOM Committee on Shipboard Hazard and Defense II held two public meetings at which SHAD veterans had an opportunity to speak to the committee. At the first meeting, statements from eight veterans helped introduce committee members to Project SHAD. At a second meeting, held in Sacramento, California, the committee heard from three panels that each included four to six veterans who spoke about their experiences during various SHAD tests, their health concerns, and their perspectives regarding key information sources or approaches to the study. The committee also received written statements submitted by other veterans who did not attend the meetings, and several veterans spoke with members of the committee staff over the course of the study.

The comments offered by SHAD veterans provided helpful insights and observations. It was clear that veterans’ experiences in the tests varied widely and that generalizations across the tests or the participating ships are difficult because the nature of the tests, test agents, and ship settings varied. However, some themes that emerged from the veterans’ remarks are described here.

Information Limitations

At the time of Project SHAD, the tests were classified as Top Secret or Secret and information about them was highly compartmentalized. Even the men who served as part of the Project SHAD Technical Staff on the light tugs, the USS Granville S. Hall, or the USS George Eastman were not given information about the purpose, operational details, or results of a test beyond what they needed to carry out their specific tasks. They were not permitted to keep any relevant records after completion of their tasks or tests. On other ships, some sailors recalled being briefed by their commanders about the ship’s participation in a chemical or biological weapons exercise, while others recalled no warning before their ship was sprayed with a substance unknown to them. In other cases, some SHAD veterans were keenly aware that they were participants in simulant testing because they wore dosimeters to evaluate their exposure to the test agent or thermometers to monitor their physical status while wearing protective gear. Several of the veterans remembered strong admonitions not to share information about the tests, with threats of severe punishment for violators.

Some of the veterans who spoke to the committee also noted gaps or missing items in their medical records. For example, certain of the PSTS veterans recalled being given multiple vaccinations (e.g., against tularemia, Q fever, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis) prior to their involvement in tests of biological agents. However, the veterans reported that these vaccinations were not recorded in their regular medical records when those records were retrieved years later (Testimony to IOM Committee on Shipboard Hazard and Defense II, February 2012). Similarly, a veteran who remembered several visits to sick bay during the time of the test he was involved in found no record of these medical visits when he requested and received his medical records from the Navy (Personal communication, G. Arnold, SHAD veteran, USS Navarro, Sacramento, California, February 23, 2012). Limited access to detailed information about the SHAD tests continues to be a concern to veterans. As noted in Chapter 1, many of the operational details of the tests remain classified; only report pages deemed “medically relevant” were declassified and made public (Morris, 2004). Veterans at the committee’s workshop questioned the need for continued secrecy regarding details of the tests and their results because the types of ships that were used are no longer in the Navy’s fleet.

Because of the limitations of the information that has been declassified, veterans must rely on their recollections from the 1960s to fill in details beyond the information available in the DoD Fact Sheets and the redacted technical documents. As several veterans acknowledged, it is difficult to be definitive about events from that period.

Because the available information is limited, at least some veterans expressed concerns about the committee’s ability to refine assessments of exposure beyond the steps taken in the IOM SHAD I study. This issue is discussed further in Chapter 3, Study Approach and Design.

Involuntary Participation

Another concern is the involuntary nature of their participation in the tests. Although participation as a member of the PSTS was nominally voluntary, it took place within the command structure of military service. The regular crew members of the ships involved in the testing and the Marines in participating units reported no options regarding participation, including in particular those who were identified to provide gargle samples or run sampling stations.

Uninformed VA Staff

Veterans expressed to the committee and the IOM staff their ongoing frustration with the lack of knowledge about the SHAD tests in the VA health care system. Public Law 110-387, the Veterans’ Mental Health and Other Care Improvement Act of 2008, provided for veterans who participated in Project 112 (which included the SHAD tests) to be enrolled in Priority Group 6 for health care at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).13 As a result, VA issued a directive (VHA, 2009, 2015) that these veterans “are eligible to receive needed VA hospital care, medical services, and may be provided nursing home care for any illness notwithstanding insufficient medical evidence to conclude that such illness is attributable to such testing. No copayments apply to the receipt of this care” (VHA, 2015, p. 1). The VHA 2009 policy called for these

______________

13 VA established Priority Groups as a means to make sure that some groups of veterans are able to be enrolled before others. Priority Groups range from 1 to 8, with 1 the highest priority for enrollment. Eligibility for Priority grouping takes into account factors such as the extent of service-connected disability, employment, receipt of various medals, and income (VA, 2015).

veterans to be offered “a thorough clinical evaluation by a knowledgeable VA primary care provider; enhanced priority for enrollment in the VA Health Care System; and pertinent information about Project 112 SHAD exposures and possible related adverse health effects” (VHA, 2009, p. 2). Nevertheless, SHAD veterans reported continuing to encounter VA health care providers who had not heard of SHAD and therefore do not have an appropriate context for evaluating health issues brought to them by the veterans.

SHAD veterans seeking disability benefits from VA also expressed frustration about the need to document their participation in Project SHAD even though security procedures did not permit them to keep records or other documentation when a test was completed. The SHAD veterans contrast their circumstances with those of veterans who served in Vietnam who are presumed to have been exposed to Agent Orange when they are seeking to qualify for a service-connected disability for one of the conditions that has been defined as associated with Agent Orange exposure. The SHAD veterans had unwitting or at least often involuntary participation in tests of chemical or biological agents or simulants and see justification for establishing a presumption that their participation in these tests qualifies them for service-connected disabilities. There is currently no finding of specific conditions associated with SHAD exposures, however, and that is an impetus for the research questions for this study.

Members of the PSTS had a unique experience within the SHAD tests, and they have a special set of concerns. These men participated in tests that used not only simulants and related test substances but also active biological agents. In addition, many of these men had unusual working conditions as a result of serving as crewmen on the five light tug boats that had been refitted to be used as sampling stations. PSTS members noted to the committee that these tugs were designed for service in a harbor and not in the open ocean where SHAD tests were conducted.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Project SHAD included a diverse set of tests conducted during a 7-year period in which more than 21 Navy vessels, several Marine ground units, and at least eight Marine or Navy air units participated in some manner. An understanding of the nature and diversity of the tests, gained from both veterans and DoD documents, was important in helping the committee frame its approach to the analysis of the available data on test exposures and health outcomes. Chapter 3 reviews several issues that were important in shaping the analysis.

REFERENCES

Beard, V. L. 1996. Letter to Mel Hancock, U.S. House of Representatives. October 28, Washington, DC: Special Actions Branch, Department of the Army.

DoD (Department of Defense). 2003a. Deseret Test Center, Project SHAD: Autumn Gold (Update). Factsheet, Version 12-2-2003. Washington, DC: The Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Health Affairs), Deployment Health Support Directorate. http://mcm.fhpr.osd.mil/Libraries/CBexposuresDocs/autumn_gold_revised.sflb.ashx (accessed May 13, 2014).

DoD. 2003b. Deseret Test Center, Project SHAD: DTC Test 70-C. Factsheet, Version 6-30-2003. Washington, DC: The Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Health Affairs), Deployment Health Support Directorate. http://mcm.fhpr.osd.mil/Libraries/CBexposuresDocs/dtc_test_70_C.sflb.ashx (accessed January 13, 2015).

DoD. 2003c. 2003 Report to Congress: Disclosure of information on Project 112 to the Department of Veterans Affairs as directed by PL 107-314. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Health Affairs).

DoD. 2004 (unpublished). SHAD test information. Provided to the Institute of Medicine in response to an information request submitted by Susanne Stoiber, Executive Officer, Institute of Medicine, to William Winkenwerder, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, Department of Defense. Washington, DC.

DoD. 2011. Release from “secrecy oaths” under chemical and biological weapons human subject research programs. Memorandum from William J. Lynn III, Deputy Secretary of Defense, January 11. http://mcm.fhpr.osd.mil/Libraries/CBexposuresDocs/OSD_14995-10.sflb.ashx (accessed January 14, 2014).

DoD. 2014. Project 112/SHAD—Shipboard Hazard and Defense. http://mcm.fhpr.osd.mil/cb_exposures/project112_shad/shad.aspx (accessed January 3, 2014).

DoD. 2015. Project 112/SHAD fact sheets. http://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/HealthReadiness/Environmental-Exposures/Project-112-SHAD/Fact-Sheets (accessed October 15, 2015).

DTC (Deseret Test Center). 1963a. Autumn Gold (U). Revision 1, Test Plan 63-2, April 1963, Appendix H, Defensive Tests, Part I. Redacted excerpts. Fort Douglas, UT: Deseret Test Center.

DTC 1963b. Autumn Gold (U), Revision 1, Test Plan 63-2, April 1963, Appendix K. Redacted excerpts. Fort Douglas, UT: Deseret Test Center.

DTC. 1964. Autumn Gold (U). Test 63-2, Final Report, May 1964. Redacted excerpts. Fort Douglas, UT: Deseret Test Center.

DTC. 1965a. Test 64-2—Flower Drum (U), Phase I. Final report—Revised. December. Redacted excerpts from pp. cover, iii, iv, 3-5, 7-9, 11, 13, 20, 22, 28, 57, 63. Rpt. No. DTC 642110R. Fort Douglas, UT: Deseret Test Center.

DTC. 1965b. Test 64-2, Flower Drum (U), Phase II, Final Report, October 1965. Report Number DTC 642105R. Redacted excerpts. Fort Douglas, UT: Deseret Test Center.

DTC. 1965c. Test 64-4 Shady Grove (U), Final Report, December 1965. Redacted excerpts. Headquarters, Fort Douglas, UT: Deseret Test Center.

EPA (Environmental Protection Agency). 2014. Clean Air Act requirements and history. http://www.epa.gov/air/caa/requirements.html (accessed January 14, 2014).

GAO (General Accounting Office). 2004. Chemical and biological defense: DoD needs to continue to collect and provide information on tests and potentially exposed personnel. GAO-04-410. Washington, DC: General Accounting Office.

GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2008. Chemical and biological defense: DoD and VA need to improve efforts to identify and notify individuals potentially exposed during chemical and biological tests. GAO-08-366. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office.

Gober, H. W. 2000. Letter to William S. Cohen, Secretary, Department of Defense. August 3, Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2007. Long-term health effects of participation in Project SHAD (Shipboard Hazard and Defense). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2008. Response to 15 February 2008 letter from Congressmen Mike Thompson and Dennis Rehberg. http://iom.nationalacademies.org/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2007/Long-Term-Health-Effects-of-Participation-in-Project-SHAD-Shipboard-Hazard-and-Defense/SHAD%20Response%20Letter.pdf (accessed October 7, 2015).

Kang, H. K., and T. Bullman. 2009. Mortality follow-up of veterans who participated in military chemical and biological warfare agent testing between 1962 and 1972. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 72:1550-1552.

McKim, W. D. 2013. Interim technical report on CBAIMS and U.S. Chemical and Biological Tests Repository from September 2011-May 2013. Washington, DC: Batelle.

Morris, D. D. 2004. The Department of Defense identification of participants and exposures in Projects 112 and Shipboard Hazard and Defense. M.P.H. Thesis, Morris, Dee Dodson: George Washington University.

Murphy, J. 2003. Secrecy over Cold War WMD tests. CBS News, July 1. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/secrecy-over-cold-war-wmd-tests (accessed January 13, 2015).

Nixon, R. 1969. Remarks announcing decisions on chemical and biological defense policies and programs. November 25. Online by G. Peters and J. T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=2344 (accessed January 14, 2014).

VA (Department of Veterans Affairs). 2015. Health benefits: Priority groups. http://www.va.gov/HEALTHBENEFITS/resources/priority_groups.asp (accessed January 21, 2015).

VHA (Veterans Health Administration). 2009. Provision of health care services to veterans involved in Project 112-Shipboard Hazard and Defense (SHAD) Testing. VHA Directive 2009-047, September 30. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs.

VHA. 2015. Provision of health care services to veterans involved in Project 112-Shipboard and Land-based Hazard and Defense Testing (Project 112/SHAD). VHA Directive 1127, March 24. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs.