The following working definition of governance for global infectious disease control was provided in the workshop agenda:

In the context of infectious disease outbreaks of global significance, governance encompasses a range of integrated policy, information management, command, and control mechanisms for facilitating collective action to achieve the objectives of prevention, detection, and response. Of necessity, these mechanisms integrate actions across intergovernmental organizations, sovereign nations, communities, the corporate sector, humanitarian agencies, and civil society. They operate in not only the realm of health, but also to a variable extent in collateral spheres to include agriculture/ food security, diplomacy, education, finance, migration/refugee care, security, and transportation.

This chapter discusses the varying ways of defining “governance for global health” and the implications a definition may have on the structures that follow. Speakers considered challenges of the current system, recent changes in the diversification of players involved in the global health field, and the continuing need to create linkages between all levels of government.

DEFINING GOVERNANCE FOR GLOBAL HEALTH

From his perspective as a politician and global health diplomat, Keizo Takemi, professor at Tokai University, called for collective action to address infectious diseases that threaten human security. A member of the Japanese House of Councillors and the Liberal Democratic Party, Takemi emphasized the role of health in security at every governmental level. In Japan, he noted, infectious diseases increasingly are regarded as threats to national security, and policy makers have recognized the importance of controlling infectious threats at the earliest possible stage. As hosts of the 2016 G7 summit, Japan will contribute to international discussions on governance for global health—discussions they attempted unsuccessfully to initiate in 2008, he reported. Since then, efforts to define what global governance encompasses, in a world lacking any such authority, have been spurred by humanitarian crises with global repercussions, among them emerging infectious diseases.

Takemi offered two contrasting definitions of governance for global health: “the way in which the global health systems are managed” and “the organized social response to health conditions at the global level.” Both concepts raise a series of fundamental dilemmas, he noted: the lack of government at the global level, the critical influence decisions made outside the health sector (e.g., trade, defense, and immigration) have on health, and the increasing role of nonstate actors in the response to global health crises.

The issue of sovereignty often impedes critical discussion of these dilemmas by decision makers, Takemi observed. Politicians do not want to be perceived as interfering with the sovereignty of nation states, yet global governance demands it. Similar tensions hindering collective action arise between international agencies with deep organizational interests. Less inflammatory (but equally obstructive) barriers between sectors narrowly limit the scope and effectiveness of decision making, while the proliferation of nonstate actors in the health sector further complicates the response. The West African Ebola crisis starkly illustrates these roadblocks and their consequences for collective action to ensure global health, Takemi stated. He acknowledged the failure of three decades of well-documented warnings on the potential impact of emerging infectious diseases (and other global health threats) to galvanize sufficient political will to avert the Ebola tragedy.

Infectious Disease Preparedness and Response: The Road to the IHR

David Fidler of Indiana University defined the overarching goals and essential properties of good governance for global health as applied to infectious disease preparedness and response, and described the political context for implementing these elements through the IHR. Tracing the evolution of the concept of global governance for infectious diseases, he examined its status in the wake of the West African Ebola outbreak. Many definitions of global health governance—including the previously included working definition—tend to focus on actors, processes, principles, and objectives, neglecting or obscuring the central act of exercising political power, Fidler observed. The extent to which the exercise of political power is “good” can be evaluated on the basis of attributes such as legitimacy, transparency, accountability, equity, justice, and effectiveness, he explained.

Well before the West African Ebola epidemic, efforts were made to reform the institutional architecture for global health governance that “didn’t go anywhere,” Fidler recalled. Instead, a new strategy was adopted that united global health with global security. “Through global health security, we were trying to rethink what we meant by health; we were rethinking the idea of security, national and international security,” he explained. The resulting pluralistic global health security concept was based on principles of good governance such as participation and organization. The embodi-

ment of the global health security strategy as applied to infectious diseases was the IHR 2005: a strategic effort to fulfill the categories of “good governance,” Fidler remarked. Featuring participation by state and nonstate actors, its function was prevention, protection, and response against known and unknown epidemic threats. It empowered WHO and its leaders in new ways, and it integrated national security, economic interests, and human rights. The IHR 2005 was a vast improvement over the ineffective 1969 version of the IHR, he stated.

Ebola, however, caused problems on several fronts, Fidler said. An outbreak response that was initially open and inclusive for those willing to help lapsed into dominance by major powers; the need to address a humanitarian disaster in addition to controlling an outbreak—a situation not anticipated in the IHR 2005—resulted in a crisis in leadership; and principles of national security, economic interests, and human rights were damaged or seriously threatened. Although the crisis was eventually brought under control, this was achieved not through organized collective action, but through an expeditionary military campaign combined with the efforts of several ad hoc organizations and foreign member states, he concluded.

This disaster, Fidler hypothesized, resulted from “the gap between what we think we have as governance and the actual essence of governance, which is the exercise of political power.” At the World Health Assembly (WHA) meeting in May 2015, he noted, WHO member states expanded WHO’s responsibilities but did not increase assessed contributions. The WHA did not seek accountability for WHO’s failed response to Ebola, nor did they agree on ways to interact more productively with civil society. WHO member states agreed to a new emergency fund, but one supported only by voluntary contributions, which can lead to accountability issues. Such weak efforts to improve global health governance for infectious diseases were overshadowed by those of other institutions, such as the G7, the Global Health Security Agenda, and the World Bank Group, he said—evidence that proliferation in governance is occurring without “any serious connection to how political interests are formed or political power is exercised.”

Jeffrey Duchin of Seattle–King County Public Health and the University of Washington, asked for examples of instances in which the exercise of political power with regards to global health has been reconciled with principles of good governance. Fidler said that the IHR in their conception represented an alignment of political interest and the willingness to exercise political power that moved global health governance forward. However, the IHR fell short in the Ebola crisis because political support for them did not last when they were first enacted, and compliance with the core capacities of the IHR was not enforced. Among proposed post-Ebola models of global health governance for infectious diseases, some of which bypass WHO, it

remains to be seen whether the exercise of power—through the commitment of resources such as money, political capital, influence, capabilities, and personnel—would adhere to the principles of good governance, he stated.

Including Other Nonstate Actors in Global Governance Discussions

Responding to this point, WHO Director-General Margaret Chan observed that partnerships and donors outside WHO often neglect less wealthy and powerful countries, but insisted that those are the voices that need to be heard. However, she also urged change in WHO and United Nations (UN) agencies to reflect the fact that no existing government can provide the services and support needed to address health crises such as Ebola without the engagement of nonstate actors, including civil society, academia, and industry. Unfortunately, during the Ebola crisis, WHO member countries could not agree to include nonstate actors as part of the debate and discussion, she recalled.

“The legitimacy of WHO as a place where less powerful countries can come and have a voice obviously is not shared by those governments that want to go outside WHO in order to get something done,” Fidler observed. Does that decision reflect the good governance notion of legitimacy, he wondered? How can the political interests of nonstate actors be brought into alignment with WHO’s authority? Duchin asked if it were possible to plan for the possibility that political interest and power might not align to produce good governance in a future crisis. Fidler did not think it could be anticipated, only remedied after the fact, as is now being contemplated concerning revisions to the IHR, which for many countries has become merely a checklist that did not align with their own national health priorities. Peter Piot of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine argued that power relations can evolve, and WHO needs to remember to look broadly across the global health field when considering interests.

Fidler, however, predicted that such seemingly limited “fixes” to the global health governance system would have far-reaching and unanticipated consequences due to the system’s complexity. “We need to prevent trying to find the solution to today’s problem,” Alejandro Thiermann of the OIE argued, using H5N1 as an example. Every time there is an outbreak, the focus is on that specific need, but following H5N1 the next epidemic was severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), he noted, for which the world was unprepared. Thus, between crises, global health should concentrate on assisting countries that have the will and not the means to comply with international norms. Doing that effectively requires monitoring and measuring improvement, he advised, and adjusting approaches to maximize preparedness for the next crisis in an all-hazards manner.

Performance of Veterinary Services Pathway:

A Potential Model for Governance

Thiermann described the design and implementation of compliance-enhancing mechanisms to drive good governance as embodied in the international Terrestrial Animal Health Code. He also discussed the various means by which compliance with these measures has been monitored, measured, supported, and improved. Expanding the definition of “global health” to include animals, plants, and ecosystems, according to the concept of One Health,1 Thiermann defined global veterinary governance as a global public good. He described the OIE’s efforts to establish, monitor, and encourage worldwide compliance with standards for veterinary services.

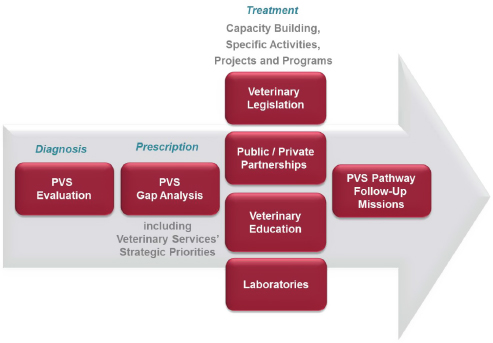

Founded in 1924 in the wake of an outbreak of rinderpest in Europe, the OIE is comprised of 180 member countries, which host its 301 centers of expertise. The organization’s mandate has since evolved to encompass information sharing on animal health issues and threats, scientific collaboration, and the establishment of international standards for terrestrial and aquatic animal health, Thiermann explained. To address the later goal, OIE developed its Performance of Veterinary Services (PVS) Pathway (OIE, 2013) (see Figure 2-1), which he described as a “system of measurement and evaluation that is an effective foundation for improving animal and public health at the national, regional, and international levels.”

The continuous process that is the PVS Pathway begins with a request to the OIE from a member country for evaluation of its veterinary services, Thiermann said. The OIE-trained experts, approved by the country, conduct a qualitative assessment of national performance on 47 criteria specified in the OIE’s terrestrial animal code. Those standards are focused in the following four areas: human, physical, and financial resources; technological capability and authority; interaction with interested parties; and market access. Each of these competencies is judged on a five-point scale, he explained, and it is up to the country to decide whether to publicize the confidential results of the evaluation. Of its 180 member countries, 133 had requested an evaluation as of April 2015, he reported; 123 have been completed, 69 are available on a restricted basis, and 20 are published on a public website. This illustrates some of the differences between the public and transparent process of the PVS Pathway and the OIE evaluations, and the closed process that member states go through regarding self-assessment in reporting compliance with WHO’s IHR. For achieving core competencies of the IHR, only 30 percent of countries have declared themselves compli-

___________________

1 The One Health paradigm has been defined as “the collaborative effort of multiple disciplines—working locally, nationally, and globally—to attain optimal health for people, animals and the environment” (AVMA, 2008).

SOURCE: Thiermann presentation, September 1, 2015.

ant after they were enacted in 2005, with no country lists or assessments posted publicly.

After reviewing the evaluation, the member country can request a visit from another OIE expert panel in order to plan and budget strategic actions over 5 years to improve compliance with the OIE PVS standards in the general areas of trade, animal health, veterinary public health, veterinary laboratories, and management and regulatory services. As of April 2015, 96 countries had requested this gap and costing analysis, he said; 80 had been completed, and the results of 13 were available on the Internet. Additionally, in many countries, veterinary legislation is outdated or inadequate, Thiermann pointed out. Thus, any OIE member country that has undertaken a PVS evaluation may request a mission to advise and assist them in modernizing national veterinary legislation according to the OIE Animal Health Code. Also, 3 to 5 years after receiving a “gap evaluation” or legislative mission, an OIE member country can request a follow-up mission to measure progress toward implementing the PVS Pathway, he noted.

Combining the results of PVS evaluations conducted to date, Thiermann presented a “global PVS diagnosis” in which he identified several common weaknesses, some noticeably similar to IHR compliance weak-

nesses. These include gaps in the chain of command between local, regional, and international agencies; shrinking budgets for veterinary services; unsuitable veterinary legislation; an aging population of veterinary practitioners; absence of and lack of control over veterinary paraprofessionals such as laboratory and field technicians; inadequate emergency preparedness and response; underperforming surveillance and laboratory networks; and product safety and sanitation failures, such as the development of antimicrobial resistance. To address these shortcomings, the OIE and its member countries must collaborate with other stakeholders, including the private sector and intergovernmental organizations, he advised. Thiermann noted that the OIE and WHO, in collaboration with the World Bank, are currently investigating ways to harmonize their assessments of national capacity for disease management, using tools and indicators from both the PVS Pathway and the IHR. While this initiative offers potential to improve response to infectious diseases, he said, further investment must be made in disease prevention, such as helping countries comply with obligations as expressed by the OIE or the IHR, and rewarding transparency in reporting infectious disease outbreaks.

The OIE’s support of the PVS Pathway has cost less than $10 million to date, most of it derived from donations from member nations to the organization’s trust fund, Thiermann pointed out. When asked how being independent from the UN system affected the OIE’s ability to fulfill its mission, he replied, “I think it is certainly a plus that we are not in the United Nations in the sense that it [the OIE] is a very small, flexible organization.” As such, he said, the OIE can make rapid, technical decisions under relatively little influence from government or private-sector interests. While their budget is limited, member donors have built a trust fund that is currently three times the size of the OIE’s annual operating budget, he reported. This has allowed them to support some capacity-building activities of their own, in addition to investments by the World Bank that are informed by the PVS Pathway.

DIVERSIFICATION OF GLOBAL HEALTH

Focusing on the concept of global health governance as it is applied to infectious diseases, Fidler described the dramatic expansion in expectations for “good governance” in this arena since the mid-1800s. At that time, global governance for infectious diseases was initiated under the International Sanitary Conferences and International Sanitary Conventions. Subsequently, institutions such as WHO, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, and the United Nations Environment Programme began to complicate the picture, leading to today’s broad spectrum of governance actors, which also includes the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Joint United Nations Programme

on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the G7, the Global Fund,2 and the Gates Foundation. This expansion occurred through a series of “proliferation moments” associated with specific infectious disease threats, he explained, including HIV/AIDS and UNAIDS; emerging infectious diseases and the Global Fund; and SARS and the 2005 revisions to the IHR. Another such “proliferation moment” may follow from the Ebola crisis, he observed.

The increasing ranks of actors on the stage of global health governance are creating major political problems, according to Fidler. Competition for scarce resources has led to complaints that some diseases (e.g., HIV/AIDS) receive funding disproportionate to that of other health threats. The vast array of actions, processes, and mechanisms promulgated by multiple actors creates tension over agenda setting and has undermined the authority of WHO, once considered the central international agency for health governance. This lack of coordination has prompted calls for “collective action on collective action,” as exemplified by Takemi’s previous statements.

Amid greater awareness of and attention to global health, the field has become more diversified and less dominated by WHO, Takemi added. For example, he said, UNAIDS was created in 1996 to respond specifically to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, while UNICEF and the United Nations Population Fund have each developed strategies for child, maternal, and reproductive health that are not formally coordinated. At the same time, nonstate health organizations, which lack political accountability, have increased in numbers and presence. However, the legitimacy of these nonstate actors has been enhanced by their inclusion in the governance of stakeholder organizations such as the Global Fund.

How to Leverage the Private Sector

Public–private partnerships have also proliferated to address global health concerns. Takemi described Japan’s Global Health Innovative Technology Fund,3 a consortium representing pharmaceutical companies and government representatives from several sectors, and partnered with the Gates Foundation and the Wellcome Trust. Such schemes, he asserted, encourage research and development on the part of pharmaceutical companies to meet global health threats arising among impoverished populations, as exemplified by Ebola in West Africa. The Ebola outbreak hit an area where people are particularly vulnerable and have suffered poverty for a long time, Takemi said. Under these circumstances, neither the nation states nor the intergovernmental organizations were able to effectively pre-

___________________

2 The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, see http://theglobalfund.org/en (accessed April 18, 2016).

3 See https://www.ghitfund.org (accessed January 8, 2016).

vent, contain, or control the spread of Ebola. Instead, the risk of infections gradually expanded to other countries, leading the world to question the effectiveness and the legitimacy of the existing global health framework.

This situation demonstrates the need to create linkages among all levels of government and nonstate actors—beginning with the community—and to provide support where governance is weak, Takemi stated. People still rely on and are influenced by the decisions of the traditional leaders, he noted, and national and local governments can build larger-scale responses sustainably on the foundation of existing community structures. Piot also observed that the proliferation of global governance actors happened because the world is increasingly interconnected. However, the situation demands consolidation at a governance level on a par with the UN Security Council. Further, he advised, an agreement should be brokered among WHO member states and other political powers in order to delegate responsibility in a health crisis. It is time to fix this specific problem, rather than overhaul global health governance, he concluded.

STRENGTHENING EXISTING SYSTEMS

Examining the implications of these challenges, Takemi first discussed the need to enhance resilient and sustainable health systems through collective action at multiple levels of governance.4 Health systems must address the wide-ranging effects of poverty, civil upheaval, cultural beliefs, and other factors that undermine health, he insisted. He described the experience in Japan showing that it is necessary and effective to develop and implement a comprehensive policy package that incorporates social welfare, labor, economy, trade, and industry to tackle various socioeconomic challenges and maximize opportunities for growth. For example, in the 1950s and 1960s, such policies not only spurred the development of effective drugs for tuberculosis and high blood pressure by Japanese companies, but also expanded access to community-based, preventive health care. In examining options “post-Ebola outbreak,” Takemi encouraged increased attention to the community-centered approach, as they are the targeted audience.

Takemi also advocated that WHO continue to play the leading role in addressing infectious disease outbreaks and characterized the criticism leveled against the organization for its delay in declaring the Ebola epidemic a public health emergency of international concern as unfair, saying it was fueled by a vast array of unfortunate factors. We should take this opportunity to increase the political momentum around global governance and

___________________

4 As part of the Global Health Risk Framework, a separate workshop summary on building resilient and sustainable health systems explores these concepts in more depth and can be found at http://iom.nationalacademies.org/reports/2016/GHRF-Health-Systems.

leadership issues, he advised, including at the next G7 summit. To secure and sustain financial resources for emergency responses, the World Bank Group has proposed the creation of a pandemic emergency facility in conjunction with WHO and private-sector partners. An insurance mechanism, activated by crisis, would trigger companies to fund the facility, which in turn would pass on resources to the agencies involved in a containment effort, he explained.

Overcoming the IHR’s insufficiency to contain the spread of infectious diseases will require action on multiple fronts and involve several nonhealth sectors, Takemi noted. For example, enlisting the WTO to mitigate disincentives to report infectious disease outbreaks could help achieve this. Noting that only one in three WHO member states has achieved health capacity goals mandated by the IHR (WHO, 2015c), he advocated the creation of financial incentives for nations that report health emergencies, provided through the global health governance framework. He also emphasized the need for strong leadership, at the level of heads of state, and extending beyond the health sector, as well as international solidarity to support common political approaches.

While models presented at the end of this summary explore a new agency as an option, Takemi argued that no new agency is needed to coordinate the spectrum of organizations responding to global health emergencies. However, he said, WHO does need to work more closely with other UN agencies (e.g., UNICEF, the Food and Agriculture Organization, and the World Food Programme) and with the World Bank Group to influence global and national policy, as well as to respond to specific health threats. Mechanisms must be developed to coordinate the efforts of these agencies with groups delivering services to affected populations, such as nongovernmental organizations and military units, he added. Incorporating many different international agencies, each with their own politics, will be challenging, he warned. However, improved collective action can lead to progressively developing a tangible coordination mechanism to mutually accompany bilateral cooperation and enhanced collaboration with nonstate actors.

In conclusion, Takemi envisioned a common policy extending from the community level on the foundational concept of human security, and linked to collective action at the national and global levels. Proposals for strengthening global governance for health need to be aligned and supported by both effective leadership and political action, he insisted, saying that governance is not just architecture. Looking toward the 2016 G7 summit, Takemi noted that Japan would participate in continued discussion of global health issues at several interim international meetings, as it prepares policy recommendations.

This page intentionally left blank.