In this chapter, various lessons emerging from past global outbreaks of infectious disease are explored through multiple perspectives, from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2005, to H1N1 in 2009, to the recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa, each of which marked a milestone in the history of the IHR. Participants synthesized what information has surfaced from these and other infectious disease challenges to inform efforts to strengthen and better coordinate governance for global health, and to identify ways to modify the IHR to allow it to achieve its intended purpose.

SARS AND THE 2005 REVISION OF THE IHR

The first IHR—legally binding regulations agreed upon by all nations represented by WHO, as described in the introduction to this overview—became law in 1969. Reflecting that less globalized world, they were intended to stop infectious diseases at national borders, and to ensure the maximum security against the spread of disease with a minimum interference in world traffic, explained David Heymann of Public Health England/ Chatham House. The IHR 1969 required countries to

- Notify WHO of outbreaks occurring within their borders of three infectious diseases: cholera, plague, and yellow fever (such reports were accepted from countries in which the event occurred);

- Take only those protective measures against these diseases specified by WHO via the IHR; and

- Equip their borders (e.g., ports, airports, and frontier posts) adequately to prevent vector proliferation.

At that time, WHO published the outbreak reports it received “in very small print on the back of the weekly Epidemiological Record,” Heymann recalled. Other countries could choose to react by, for example, requiring travelers from a country experiencing an outbreak of yellow fever to show proof of vaccination against the disease upon entry. But by the 1990s, with the rapid expansion of international trade and tourism, the economic impact of reporting the IHR-required diseases—which mainly affected developing countries—had become severe. Moreover, the regulations failed to address the growing threat of emerging infectious diseases, influenza, and other unknown threats.

In 1996, the WHO Director-General established an emerging infections program that in part was tasked with revising the IHR based on a 1995 World Health Assembly (WHA) resolution. The vision for the revised IHR was “a world on the alert and able to detect and collectively respond to international infectious disease threats within 24 hours, using the most up-to-date means of global communication and collaboration,” Heymann said. These revisions were intended to establish a climate in which infectious disease outbreak reporting, while not enforced, was expected and respected. Implementing this vision within WHO required several key policy decisions—many of them precipitated by the emergence of SARS—Heymann explained.

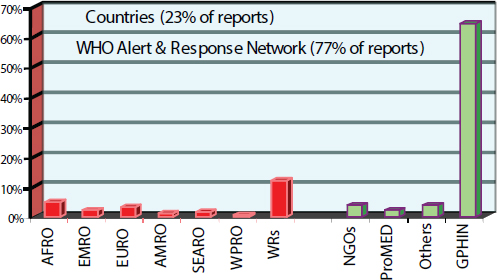

The first was a move to act on information about disease outbreaks from sources other than countries, such as the Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases (ProMED)1 and the Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN)2—again showing the importance of understanding the proliferation of the players on the global health field that can support IHR goals. As compared with countries, these nonstate sources delivered far more actionable surveillance that controlled infectious disease outbreaks, he noted (see Figure 3-1).

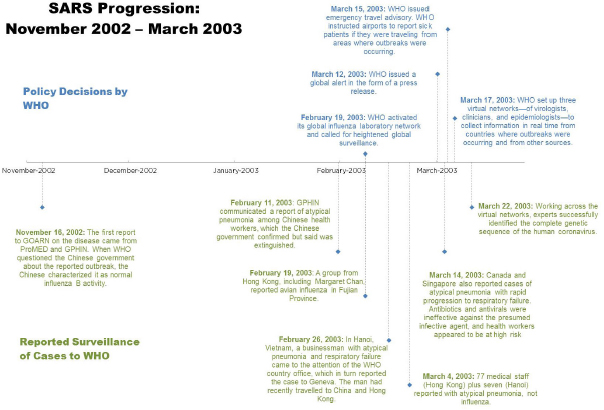

The first report to the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) on the disease that would be named SARS came from ProMED

___________________

1 ProMED is an Internet-based reporting system dedicated to rapid global dissemination of information on outbreaks of infectious diseases that affect human health. For more, see http://www.promedmail.org (accessed November 18, 2015).

2GPHIN, developed by Health Canada in collaboration with WHO, is a secure Internet-based multilingual early warning tool that continuously searches global media for information about disease outbreaks. For more, see http://www.who.int/csr/alertresponse/epidemicintelligence/en (accessed November 18, 2015).

NOTE: AFRO = WHO Regional Office for Africa; AMRO = WHO Regional Office for the Americas; EMRO = WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; EURO = WHO Regional Office for Europe; GPHIN = Global Public Health Intelligence Network; NGO = nongovernmental organization; ProMED = Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases; SEARO = WHO South-East Asia Regional Office; WHO = World Health Organization; WPRO = WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; WR = WHO representative.

SOURCE: Heymann presentation, September 1, 2015.

and GPHIN and occurred on November 16, 2002. (See Figure 3-2 for a full timeline of the SARS surveillance and detection evolution, as well as policy decisions prompted by events.) The route by which SARS achieved international transmission and factors contributing to local case clusters were identified by Margaret Chan’s epidemiologic team in Hong Kong, Heymann noted.

They shared this information globally, leading to another policy decision by WHO: recommending that travelers avoid countries where environmental transmission could be occurring, a decision that profoundly affected economies and industries. In a break with prior policy, WHO then decided in April to publicly criticize the Chinese government for failing to report the initial SARS outbreak. This was a decision that was very difficult for the Director-General to make, Heymann said—but it got results, and the SARS pandemic was extinguished by mid-July.

NOTE: GOARN = Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network; GPHIN = Global Public Health Intelligence Network; ProMED = Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases; SARS = severe acute respiratory syndrome; WHO = World Health Organization.

SOURCE: Adapted from Heymann presentation, September 1, 2015.

It was fortuitous that WHO had developed the vision of the IHR reform before SARS struck, and also that the WHA occurred amid the pandemic, providing an opportunity to institutionalize policy decisions made during the crisis, Heymann said. Thus, in 2003, the WHA approved new norms for reporting and responding to infectious diseases, including the use of reports from nonstate sources, the reporting of all infectious diseases with potential for international spread, and a formal framework for proactive international surveillance and response to all PHEICs.

The resulting 2005 revision of the IHR moved the focus of the regulations from controlling infectious diseases at borders to detecting and containing diseases at their sources by strengthening core capacity and, as Heymann observed, “from passive to proactive, using real-time global surveillance evidence, and from three diseases to all public health threats.” Briefly, the IHR 2005 addressed the following objectives:

- Strengthening national capacities. Unfortunately, Heymann noted, because national capacities are self-assessed, many countries have missed multiple deadlines and are now asking for extensions until 2016.

- Reporting all public health threats. A decision tree3 developed by the Karolinksa Institute in Sweden guides disease reporting according to tested criteria.

- Proactive surveillance. An IHR focal point in each member country provides direct contact with WHO for notification, consultation, and verification of disease threats.

- An openly accessible event management system for data entry and assessment.

- National containment of public health risks, and collaborative risk public health measures for events of international importance.

While recognizing the IHR 2005 as a significant step forward in global health governance, Heymann highlighted four perceived shortcomings of the regulations following the West African Ebola outbreak through questions to the participants. He asked: (1) Are they too restrictive as they are currently written? (2) Instead, should they focus more on core capacity with flexibility for alert and response? Additionally, he wondered if (3) they provided for the right level of community engagement required in countries where the government is not high functioning, and finally (4)—with the emphasis on the declaration of a PHEIC—he asked if they have perhaps taken the emphasis away from the pre-PHEIC response that could prevent

___________________

3 For more on this decision instrument, see http://www.who.int/ihr/publications/annex_2_guidance/en (accessed November 19, 2015).

the threshold from being met at all. Heymann later described three essential elements for preventing the need ever to declare a PHEIC:

- WHO: an organization with the expertise, staff, and partnerships necessary to stop outbreaks;

- A facilitation mechanism (possibly an external decision-making body) that determines when outbreak intervention should occur and which national core capacities need to be strengthened; and

- Broad-based, global advocacy for health security.

We should be concerned with strengthening those three areas now, rather than worrying about what happens when health emergencies occur, he argued; discussions of global governance for health risks should focus on prevention.

THE IHR AND THE 2009 H1N1 INFLUENZA PANDEMIC

Harvey Fineberg of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation described a significant test of the IHR 2005 that occurred when H1N1 influenza spread across the globe following an outbreak in Mexico, beginning in February 2009 (Fineberg, 2014; WHO, 2011). By the end of April, the virus had spread throughout the Americas, and to Europe, the Middle East, and New Zealand, leading WHO to declare a PHEIC on April 25, 2009. By June 9, when 73 countries had reported more than 26,000 laboratory-confirmed cases, WHO declared a pandemic. Some critics have since asked if this pandemic was that severe and if WHO declared the threshold too early. But as Fineberg explained, although overall incidence was in the hundreds of thousands, this pandemic ranks below the average annual influenza burden worldwide. However, high mortality among younger people raised the burden of disease considerably.

As chair of an international panel charged by the WHA and the WHO Director-General in 2010 to examine the performance of the IHR and WHO in the course of the 2009 pandemic, Fineberg examined a broad range of evidence and prepared a report that was submitted to the WHA in 2011 (WHO, 2011). Summarizing key insights from this report, he noted that this first test of the 2005 IHR revealed the following challenges:

- Vulnerabilities in global, national, and local public health capacities;

- Limitations in the availability, accumulation, and applicability of scientific knowledge in responding to the outbreak;

- Difficulties in decision making under conditions of uncertainty and stress;

- Complexities in international cooperation;

- Challenges in communication among experts, policy makers, and the public; and

- shortcomings of WHO decision making and implementation.

Fineberg discussed the report’s conclusions and their significance for global governance. Overall, the IHR 2005 “helped make the world better prepared to cope with public health emergencies,” he stated. However, mandated core national and local capacities were not fully operational in 2009, nor were they on a path to timely implementation worldwide—a situation that still persists 6 years later. However, the report did identify several areas in which the IHR 2005 had proved successful in 2009:

- Strengthened cooperation, communication, and technical support through national focal points;

- Increased country capacity for addressing pandemics, including surveillance, risk assessment, and response;

- Streamlined decision making;

- Attention given to economic and social interests; and

- Strong public health rationale and solid scientific information provided to justify health measures that affected international trade.

In addition to the previously noted failure of many member states to fulfill their capacity obligations under the IHR 2005, another major shortcoming revealed by the 2009 H1N1 pandemic was the absence of any means to enforce the regulations, as Fidler, Heymann, and others had acknowledged. These gaps, in addition to the issues raised by Heymann’s final questions, give a basis to rethink and perhaps improve on the current IHR, Fineberg suggested.

Fineberg offered international collaboration and mobilization for technical assistance as examples of ways to ease the IHR implementation process for countries. To this end, the 2011 panel recommended sharing resources, further improving the event information site managed by WHO, making appropriate resources available at the national level, and clarifying the effects of decisions made by countries in the course of their implementation of the IHR. WHO also performed well in many areas of its response to H1N1 (2009), Fineberg reported. Without discounting these successes, he turned to four key structural problems in the organization that were revealed in this crisis, and which are ongoing. First, WHO functions simultaneously as the world’s moral voice for health, and the servant of its member states. Thus, he asked, is WHO’s foremost responsibility to the member states that authorize its budget and define the agenda? Or is its higher responsibility to the health and well-being of all humanity? That tension obstructs effective governance, he suggested. The second impediment

to WHO effectiveness is its budget, which Fineberg called “incommensurate with its responsibilities.” Third, WHO’s governance structure—designed to respond to focal, short-term emergencies and also to manage multiyear disease programs—is not appropriate for mounting an intense, global response to a dynamic pandemic. In the case of H1N1 (2009), the organization was forced to rely on “volunteerism from within,” repositioning essential staff to emergency posts, which is not sustainable. Lastly—as was even more prominent in the West African Ebola epidemic—separation of authority and autonomy between WHO’s regional offices and its headquarters weakened the organization’s ability to exert “command and control” during the crisis response, Fineberg observed.

Based on their review of the global response to H1N1 (2009), the panel identified several specific challenges to consider in preparations for future health emergencies. Key challenges include WHO’s previously described structural impediments; full implementation of the IHR monitoring, reporting, and national response capacities; actionable data acquisition, monitoring, and management; communication and coordination across national and nonstate actors; and capacity, protocols, and resources to mount and sustain a comprehensive response to health threats, organized through a unified command structure. The absence of any means of enforcement for IHR compliance still persists well beyond the 2009 epidemic and continues to present a challenge in implementation. Additionally, as Fineberg stated, the conflicting roles and responsibilities of WHO and whom they are accountable to continue to stand in the way of nimble and adequate responses to global outbreaks. The reality that the world is ill prepared to respond to a severe influenza pandemic or to any public health threat stands as a core challenge to be met through global governance, Fineberg concluded.

WEST AFRICA EBOLA OUTBREAK, 2014-2015

Several speakers gave a range of perspectives regarding the response to the recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa, illuminating several areas within the IHR and lessons from past PHEICs that have yet to be remedied, as well as highlighting new and different challenges that have not been experienced in prior disease outbreaks.

Médecins Sans Frontières

Joanne Liu, president of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF; also known as Doctors Without Borders), recounted the organization’s experience of the ongoing West African Ebola epidemic (MSF, 2015a,b). MSF has responded to several Ebola outbreaks over the past two decades involving as many as

425 cases, she reported—experiences incomparable to the latest epidemic of more than 28,000 confirmed, probable, and suspected cases. MSF cared for about one-third of the 15,000 patients with confirmed Ebola, of whom about half survived. Twenty-eight MSF workers also became infected with the virus during this outbreak, and nearly half died. “There is no context in the last 10 years where we lost so many staff,” she observed. Through years of experience with Ebola, MSF has developed a six-part strategy to address outbreaks: ensuring access to care and isolating patients, contact tracing, raising community awareness, conducting alerts and surveillance, supporting safe burial and decontamination, and providing health care for non-Ebola patients. However, she noted, because Ebola spread so widely in West Africa, MSF had to compromise or abandon many of these activities in the course of the epidemic.

The West African epidemic unfolded as a series of phases, according to Liu’s description. In the first, which occurred between December 2013 and March 2014, viral transmission occurred undetected. While this often happens in early phases of Ebola outbreaks, typically it lasts only 8 weeks, which was not the case in this outbreak, allowing the virus to spread much farther geographically, largely unnoticed. Once MSF recognized the extent to which Ebola had spread throughout West Africa, the second phase began as the organization began to sound the alarm, hoping to warn the world of its severity and potential as a global threat. Liu recalled how MSF attempted, unsuccessfully, to gain public and political attention to the mounting crisis. Several factors contributed to the severity of this epidemic, as has been described in detail in subsequent reports, including the Forum on Microbial Threat’s March 2015 workshop summary, The Ebola Epidemic in West Africa (NASEM, in press). Reflecting on the many and daunting challenges faced by MSF (and eventually other responders), Liu particularly urged preparation for future Ebola outbreaks in the following areas:

- Surveillance, recognizing the potential for widespread infection;

- A pool of experienced health care workers;

- Vaccines and treatments for Ebola; and

- Rapid international response, including an international center of operation.

Weaknesses of the Response

Liu attached particular significance to two shortcomings of the response to Ebola in West Africa, namely communication with the community in terms of content. Their community conversations were “one-way” and ineffective, provoking fear among many who did not understand reasoning

behind the enforced protocols. Echoing other speakers, she lamented the vacuum of leadership at national and international levels. Recognizing that a period of denial typically follows the first warning of an imminent health crisis, she remarked that her goal, and that of MSF, is to reduce the amount of time that elapses between alarm and action. Fear of Ebola itself—with its horrific symptoms, high mortality, and lack of consensus with regard to treatment—may have lengthened this period, she speculated.

By July 2014, in the wake of 1,400 cases of Ebola and 800 deaths, a desperate MSF had reached its limit. On August 8, WHO declared Ebola a PHEIC, moving the epidemic into its third phase. Ebola had long since met the criteria for a PHEIC, Liu believed. Unfortunately, she added, WHO’s announcement, while galvanizing action, also spurred “global hysteria about Ebola,” detracting from the needed international assistance. She also observed that Ebola had been introduced into the realm of security and protection, in which patients are no longer the focus anymore, but safety of travelers and other countries is.

In May 2015, the Ebola epidemic entered a phase that Liu called “the long sprint to zero.” Cases continued to be reported in Sierra Leone at the time of the workshop in September 2015, and Liu said she expected a lengthy conclusion to the epidemic, requiring focus and commitment. She and other participants warned against shifting funding and response toward reconstruction too soon, noting that such a mistake had been made in Haiti after its catastrophic 2010 earthquake. She also emphasized Ebola survivors’ need for ongoing medical care and social support, which, if met, will help them provide valuable insights into the persistence and long-term effects of the virus, which have previously been unknown. Another consideration, now that an effective Ebola vaccine appears imminent (WHO, 2015a), is to ensure its accessibility in high-risk locations, Liu continued.

Turning to the IHR, Liu highlighted the need to understand, and then address, reasons why countries have not achieved compliance with regard to infectious disease surveillance and response. She also urged advance planning and policy—including agreements to share data, specimens, and critical information—to enable research to be conducted during future outbreaks of emerging infectious disease, in order to maximize results and avoid the delays that occurred during the recent crisis. At conferences, meetings, and workshops such as this one, discussion directed toward the technical and political means of responding to infectious disease threats tends to neglect the needs of the affected populations, Liu observed. She warned that the equation of sickness and security could contribute to a climate of fear that impedes action in a health crisis where it is most needed, and called for political will to minimize the gap between sounding the alarm and an effective response.

Lancet Harvard–London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

Independent Panel on the Global Response to Ebola

The Harvard Global Health Institute and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) convened an Independent Panel on the Global Response to Ebola in early 2015. Peter Piot served as chair of this panel and discussed the group’s meetings and charge to analyze major weaknesses in the global health system exposed by the Ebola outbreak, and their goal to offer medium- to long-term institutional changes required to address them.4

Piot expressed limited expectations for their report’s impact, saying they did not have any ambitions to reform WHO itself or the entire system, but felt there were pieces of the system that could be improved. The panel’s recommendations fall into four categories (see Box 3-1). The first of these, “preventing major disease outbreaks,” describes two recommendations, of which the first is the development of a “global strategy for national core capacities” that encompasses investment in establishing such a strategy, monitoring its performance, and sustaining national core capacities for implementing it. A similar recommendation was made at the last G7 Summit, but without a plan, timeline, or budget, Piot recalled.

The panel’s second recommendation, for “incentives for early reporting of outbreaks and science-based justifications for trade and travel restrictions,” seeks to encourage compliance with the IHR. Those incentives would include economic and financing support proposed by the World Bank as part of a pandemic emergency facility, Piot stated. However, the panel agrees that the trigger for disbursement of these incentives should be controlled not by the World Bank, but by a risk assessment carried out under the aegis of WHO or the IHR. Piot also noted the panel’s support for disincentives for violating the IHR. WHO, he stated, should have the ability to announce when national governments delay reporting diseases, or impose trade and travel restrictions without a scientific or public health rationale. Private firms such as airlines and shipping companies that impose such restrictions can be dealt with through mechanisms in the broader United Nations (UN) system, he added.

The panel’s recommendations on responding to major disease outbreaks include support for a “unified WHO Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response,” as proposed by the separate Ebola Interim Assessment Panel (discussed later in this chapter), but with the additional proviso that it be semiautonomous, Piot reported. This combined health and humanitarian agency would incorporate GOARN and the UN’s humanitarian teams,

___________________

4A report from this panel was published online in Lancet on November 22, 2015. For more information see http://thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)00946-0/fulltext (accessed November 23, 2015).

he continued, and would be led by an executive director accountable for performance to a dedicated board of directors, and supported by a protected budget, in order to shield it from outside influence. Because not every outbreak warrants a global response, the Centre would provide a “third

line of defense” for severe outbreaks that create humanitarian crises, Piot stated. That response would be triggered by a mechanism within the UN’s humanitarian system and overseen by its Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

The panel’s fourth recommendation, to “broaden responsibility for emergency declaration to a Standing Emergency Committee, with mandate to declare emergencies,” echoes UN consultant Claude de Ville de Goyet’s position that the decision to declare a PHEIC should be made by an independent advisory group, rather than by the WHO Director-General, but Piot suggested WHO should still be involved. For example, the WHO Director-General could chair the Standing Emergency Committee, but the committee should convene its own meetings, rather than wait for a request by the WHO Director-General, and their deliberations and decisions should be transparent. The proposed Standing Emergency Committee should consider replacing the all-or-nothing PHEIC with graded warnings, Piot added (similar to statements made in Chapter 7 by López-Acuña). He also related his panel’s view that the committee should be financed through assessed contributions or un-earmarked voluntary contributions from WHO member states.

The panel’s fifth recommendation, to “institutionalize accountability through an independent commission for disease outbreak prevention and response,” was inspired by the extraordinary lack of accountability associated with the response to the Ebola crisis, as well as to past health emergencies, Piot said. Rather than having ad hoc committees review what went wrong after every crisis response, there should be a systematic assessment by representatives of civil society and independent experts, as well as of governments, he advised. The panel’s proposed independent accountability commission for disease outbreak prevention and response, which could be created by the WHO Director-General, would track and analyze the contributions and impact of national governments, donors, and other responders, he explained.

Two of the panel’s recommendations concern the management and sharing of knowledge and data. The first, “framework of rules for sharing data, specimens, and benefits,” reflects the frequently ignored truth that withholding such information costs lives, Piot observed. A framework to ensure the free flow of such critical resources must be created and enforced, he said, but his panel struggled to design one that was sufficiently practical to be implemented. Similarly, the panel endorsed previous proposals to establish “a global fund to finance, accelerate, and prioritize R&D [research and development], particularly vaccines,” he reported. Concerning global governance for outbreak response, the panel first recommended “sustaining high-level global political attention to health at the UN Security Council,” reflecting their belief—as previously expressed by Fidler—that “health and

health security should be dealt with where there is a political power and in the multilateral system,” Piot explained. The goal, he added, is for the Security Council to create a global health security committee that meets regularly, and also as needed.

Describing WHO as locked in a “downward spiral,” constrained by increasingly earmarked funding and lacking the confidence and trust of many donors, Piot asserted that the organization requires a “new deal.” The panel recommended that WHO limit its responsibilities to delivering certain yet-to-be-defined core functions; this, he explained, would rescue the organization from the sometimes unrealistic and conflicting demands of its member states, and allow it to renegotiate its funding. Lastly, the panel recommended “good governance through decisive, timebound reform, and assertive leadership,” Piot reported. Leadership should also explicitly address engagement with nonstate actors, “something that the executive board of WHO does not take on at the moment,” he observed.

In concluding his presentation, Piot urged his audience to bear in mind that, while discussions of global health governance tend to be abstract, their objective is to save lives. Now that the Ebola crisis has generated new momentum for change, we must use it, he urged, “to improve what has to be improved, and to keep going what can be kept going.”

UN High-Level Panel on Global Response to Health Crises

Joy Phumaphi of the African Leaders Malaria Alliance described work to date by this separate multinational panel,5 which is chaired by the president of Tanzania, Jakaya Mrisho Kikwete. Their objective is to prepare a report, with recommendations, to advise the UN Secretary-General on ways to strengthen national and international systems to prevent, respond to, and recover from health crises. While the panel will not focus on the technical health response, Phumaphi explained that the Secretary-General will take their recommendations to the UN General Assembly for endorsement or approval. Using lessons learned from every recorded health crisis, the momentum generated by the recent response to Ebola, and information gleaned from concurrent initiatives, the panel seeks to characterize early outbreak alert and response mechanisms, as well as the recovery process, and to identify the parties responsible for implementing these activities and ensuring their completion, she said.

Perhaps because most members of this panel are politicians, they have chosen to focus first on responding to people and their communities, and then on countries, subregions, and the international community, Phumaphi noted. At the time of the workshop, the panel was in an information-

___________________

5 See http://www.un.org/press/en/2015/sga1558.doc.htm (accessed January 8, 2016).

gathering stage, had hosted three meetings, and also had visited affected communities in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, she reported. They met the heads of state, local authorities, civil society, traditional leaders, UN colleagues, private-sector groups, and civil society international NGOs who are participating in the response, and have sent a panel member to the Democratic Republic of the Congo and to Senegal, she noted, in addition to meeting with WHO in Geneva and the African regional office in Brazzaville, and attending relevant workshops. From these experiences, the panel has distilled several areas in which they plan to focus their recommendations. The first concerns WHO: how to strengthen it; what role it should play in outbreak preparedness, alert, response, and recovery; and what national, regional, and international structures and formal mechanisms are needed to support those roles. These questions relate to another area of focus she described: how to make the outbreak response mechanism more reliable.

Regarding community-level governance for health emergencies, the panel plans to identify structures and mechanisms that will enable communities to be well prepared and resilient in the face of health emergencies, as well as supporting structures and mechanisms at the corresponding national and international levels. Their considerations include community health security, engagement, and ownership; the participation of traditional leaders and community health workers and their training, care, and maintenance; the fostering of trust in the system and those responsible for it; and the implications of surveillance at the community level. Phumaphi reflected on observations by Chan and others that leadership at the country level should come from the top, from the head of state or the prime minister’s office, and also about the benefits and risks of command-and-control approaches to health governance. Whether they are health or economic or political in nature, Phumaphi assured that they would not ignore regional entities and believed they need to play a role in any new governance or response mechanisms. This reflects the panel’s general conclusion that responding to health crises goes far beyond the health sector and, thus, requires a crosscutting approach, she added.

Throughout the work of the panel, Phumaphi summarized that they are following a set of principles: to focus on people, to promote global public health as a public good, to encourage accountability and transparency, to stress the importance of leadership at every political level and in the technical sphere, to serve communities above all, and to engender trust. “We are not expecting something perfect,” she said, “but we are expecting to have something that is practical, that can be applied; something that will not sit on the shelf; and something that is adaptable and versatile.”

Ebola Interim Assessment Panel

In March 2015, Chan appointed Dame Barbara Stocking of the University of Cambridge, a former director of Oxfam Great Britain, to chair the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel, an independent group of six distinguished experts. The panel was requested to examine WHO’s response to the West African Ebola outbreak and report to the WHA in May 2015 after engaging people across NGOs and communities involved in the Ebola response. The final version of this report was published on June 30.6 Stocking presented concise versions of many of the report’s recommendations. In the realm of global health security, she emphasized the need for leadership at all levels of governance, from the community to the national to the international, and introduced the set of recommendations shown in Box 3-2.

Commenting on these points, Stocking stated that the United Nations, through its General Assembly and Security Council, is the obvious agency to coordinate high-level understanding and monitoring of the state of global health security. The involvement of the UN Security Council was crucial to controlling the West African Ebola epidemic and should be extended, she said, and the report advised that an annual global health security report be prepared for the WHA, perhaps by an independent body that could also examine WHO’s progress toward increased health emergency response capacity.

Stocking reinforced Chan’s earlier point that the IHR should engage heads of state, not just ministries of health, because these high-level decision makers are ultimately responsible and accountable for their countries’ core capacities as mandated by the IHR, as well as for honoring provisions to maximize travel and trade. To pursue universal achievement of core capacities, her panel recommended that WHO create a prioritized plan and budget. Incentives would advance this plan, and should also be applied to encourage countries to report outbreaks, she said; but to do so effectively requires knowledge of existing core capacities and monitoring of the use of incentives for their improvement. Any such assessment should be conducted independently, she added, perhaps by the sort of peer-review process employed by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE), previously described by Thiermann in Chapter 2.

The IHR stands at a crossroads, Stocking observed; the regulations, and the premises upon which they are founded, are crucial, but only if they can be delivered. At the very least, she thought new financing mechanisms are necessary to provide incentives for transparent reporting of outbreaks, as are disincentives for violating provisions of the IHR. The latter could

___________________

6 For the full Report of the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel, see http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ebola/ebola-panel-report/en (accessed November 24, 2015).

potentially be undertaken by the World Trade Organization as a nontariff issue, she suggested, but acknowledged that this raises the sensitive issue of countries’ being responsible for the health of their own people—raising the point of shared sovereignty and the difficulty of achieving that. It is important to understand that WHO’s ability to act is strongly defined by directives and financing from its member states, which had yet to agree to contribute to any contingency fund for emergency response, Stocking observed. Moreover, she added, member states must build true emergency preparation in the form of core capacity, by partnering with other agencies, the private sector, and with NGOs.

Responding to Charles Clift’s concern that WHO may not be up to the task of coordinating the global response to health emergencies, Stocking remarked that WHO’s primary role is the safeguarding of public health globally. Although WHO did not fulfill this role adequately in the Ebola crisis, she wondered, “if not WHO, who else would do this, and how would that happen?” The panel did consider this option, she explained, but after estimating the cost and time required to establish a new agency, they concluded that WHO should continue as the lead agency for health emergency response, as it is currently designated by the UN. It is expected to do that

in emergencies, but she noted that substantial change will be needed to connect that to public health emergencies such as outbreaks.

Leadership and Coordination

Stocking dismissed the concern that WHO cannot simultaneously perform normative and emergency functions, insisting that many organizations are capable of doing so with separate developmental and humanitarian functions—if they have good leadership and management. While unanimous in supporting WHO’s leadership of emergency health responses, the panel also advised formal integration of this function into the existing global humanitarian system, which includes such UN agencies as the World Food Programme and the United Nations Children’s Fund. She noted that the UN’s Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), which includes the principals of all UN agencies, as well as representatives from major NGOs engaged in humanitarian response, provides a structure for this process. Because coordination and planning is a core function of WHO, taking on this leadership role will not require hundreds of new staff positions or the creation of a separate agency.

In closing, Stocking focused on the issue of community engagement as a significant—and in some locations, ongoing—failing of the response to the Ebola crisis, and the need to establish connections with communities before health emergencies occur. In Liberia, where progress against the epidemic has been strongest, communities took charge of the response, devising and implementing appropriate solutions to transmission control. Stocking argued that, while core capacities matter for surveillance in developing countries, the effectiveness of the outbreak response in these settings depends on the fundamental level of development, especially at the community level.

ORGANIZATION AND COORDINATION

OF GLOBAL HEALTH ACTORS

Multiple areas of discussion arose in response to the information presented through examination of past outbreaks and various lessons that emerged. These key areas included consideration of which global structures to consider when questioning reorganization and ideal formats, such as WHO, GOARN, and the IHR as is currently set up. Additionally, many issues surrounding coordination were highlighted, building off the earlier section on the proliferation of nonstate actors involved in global health matters, and the difficulties of data and information sharing both prior to and during an emergency response.

Global Structures to Consider

Daniel López-Acuña, who worked for more than 30 years with WHO, insisted that any discussion of governance must address political economy as a central issue. From his perspective, the international community and some political powers have created one way or the other “a balkanization of the global health architecture and the global health governance,” he stated. Rather than “reinvent the wheel” of global health architecture, he argued for rethinking global action mechanisms to include nonstate actors. Referring to Liu’s presentation, López-Acuña characterized the West African Ebola crisis as “a history of late awakenings” involving both GOARN and the humanitarian response system of international global security. This is a problem of structure, not governance, he argued; the solution is to fix structures that failed. WHO can coordinate the necessary “global system where we can have a swift mobilization of civil and military assets of public health, clinical and logistic teams,” he advised, saying that “we don’t need to disregard or disestablish the good things that we already have in place.”

Heymann reported that WHO is working on a plan for a global health emergency workforce, which WHO Director-General Chan and others subsequently discussed. Heymann expressed his hope that such a plan would not only foster cooperation among that organization, other NGOs, civil society, and industry, but also obviate the need for WHO to hire nonsustainable staff in times of crisis. Perceived gaps in leadership at the level of global health are real, Fineberg asserted. “The point of governance is not to substitute for effective leadership, as it never can. But I think it is still important to have a governance structure, which allows leadership when it exists to exert itself in the most constructive and effective manner.”

Fineberg noted that any post-Ebola global health governance structure will be challenged by the need for sufficient representation to have legitimacy, and simultaneously, sufficient power for rapid, global decision making and action. As one efficient method to achieve this, he described a pre-positioned, predetermined, delegated, time-limited, constrained authority, agreed upon by state and nonstate actors. This workforce would activate under stated conditions to provide unified capacity for material, staff, transportation, communication, local relations, and essential resource deployment, he added.

Can the IHR Build Capacity?

The roots of the IHR lie in the colonial era, and many countries feel that the regulations’ central message is “keep your disease within your territory. Don’t bring it to me,” observed Oyewale Tomori, president of the Nigerian Academy of Science. He characterized the OIE as more successful

than WHO in encouraging the reporting of infectious disease outbreaks by affected countries, and speculated that is ultimately the case because delegates to the OIE tend to be technocrats, while representatives to the WHA tend to be politicians.

Heymann agreed with Tomori’s assessment of the IHR and warned that similar perceptions compromise the Global Health Security Agenda, among other initiatives. “That emphasizes even more why WHO is so important,” he continued. “WHO is where the countries have their confidence. WHO is what should be used to make sure that the strengthening of capacities in countries is not seen as a colonial vestige of ‘keeping those diseases out of my own country.’” Further explaining why he considers the IHR 2005 too restrictive, Heymann said that the world now waits for WHO to announce a PHEIC before responding to an infectious disease outbreak. For example, he noted, while the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus continues to emerge and spread, everybody is waiting for a PHEIC to be called when GOARN should be in there stopping it, working with the government to do so before it reaches that threshold.

Institutional systems, structures, and architecture are comprised of people, Tomori reminded the audience, and we must identify those people who are truly responsible for response to health crises. “Margaret Chan gets blamed for what is happening in WHO, when in fact the person you should be taking to court is the [WHO representative] in Guinea, and the Minister of Health in Guinea,” he argued. WHO has effectively challenged countries to take responsibility in health crises, as it did Nigeria in 2008 to address polio, he noted; it should use that power more often. “I think this meeting unfortunately should have had the African leaders here to listen to what is happening,” he added.

Heymann commented that, although an improvement, the 2005 revision to the IHR has fallen short by failing to bridge the gap between noncompliant governments and communities where the actual response to infectious disease takes place. He added that he has progressed to thinking that informal governance might be best, noting that, “informal governance avoids a lot of political difficulties . . . [and] permits better engagement of people who were involved in that governance structure. It also may be more effective.” He noted that the effective but informally governed Global Polio Eradication Initiative7 simply meets once per week by telephone to plan next steps—an example that convinced him to change his stance, held since 1996, that the IHR represented “the most important tool for the world.”

Addressing the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel’s recommendation for a WHO-developed “prioritized and costed plan to develop IHR core capacities for all countries,” López-Acuña noted that this issue should

___________________

7 See http://www.polioeradication.org (accessed April 18, 2016).

also concern national and donor governments. Little if any health-targeted development aid or funding from national investment plans has gone to support core capacity strengthening, he observed. “We are talking about strengthening the health system, ensuring global health security, but we are not putting the money where our mouth is, neither as national governments, nor as donor agencies,” he said. Stocking agreed that donor nation responsibility for ensuring core capacity must be stressed, but within the broader context of strengthening health systems overall.

Chan responded to Heymann’s announcement by asserting that both formal and informal global health governance are needed, and that this combination succeeded in limiting Ebola’s spread to Mali, Nigeria, and Senegal. The formal treaty set the tone, she explained, but ultimately she had to “pick up the phone and talk to the leaders of the country to impress upon them what are the trade-offs for action or nonaction,” she recalled. “It worked in those three countries.” To improve the effectiveness of the IHR, Chan urged the adoption of peer or independent evaluation of national health capacities, similar to the OIE’s Performance of Veterinary Services (PVS) Pathway. Informal governance would continue to come into play for noncompliance, she added, and it should enable WHO to extend its relationship with the pharmaceutical industry beyond crisis response.

Is GOARN’s Structure Sufficient?

Larry Gostin of Georgetown University remarked that Heymann had made a compelling case for creating a “nimble, flexible” workforce for response to infectious disease outbreaks and other health emergencies. Gostin wondered what role GOARN might play in this scenario, and how GOARN could be made more effective with sustainable funding, to which Heymann responded that increasing staff at WHO would not achieve this. GOARN was run by five people during the SARS outbreak, with technical support from WHO, as well as experts seconded from the United Kingdom, the United States, and other countries once the outbreak was announced. It will be important to define what WHO does as part of GOARN, he added, which should include setting up logistics platforms, helping to support governments with training, and coordinating the responders.

To maintain this workforce, WHO needs a revolving contingency fund of $2 to $3 million, Heymann stated. Because donors will supplement that amount if a major infectious disease outbreak occurs, the fund will be replenished after each such event. But, there needs to be a clear chain of command within WHO to sound the alarm when outbreaks occur, assign responsibilities in the response, and carry it out, Heymann advised. GOARN did respond to the West African Ebola outbreak in March 2014, he noted—it would be interesting to know why it did not sustain that response until

the epidemic had “gotten to zero.” GOARN’s risk assessments should be transparent and made widely available, Heymann insisted—and perhaps done by an independent committee. GOARN was calling for action on Ebola in West Africa long before it was taken, he said; if those deliberations had been transparent, perhaps GOARN’s efforts would have been more effective.

Raising Political Will

Keizo Takemi of Tokai University reinforced Liu’s message that political will drives the global response to health crises. He noted that, prior to its action on the West African Ebola crisis, the UN Security Council had accepted two resolutions pertaining to HIV/AIDS (which has claimed far more lives than Ebola) but had not acted on SARS or H1N1. To politicize an infectious disease threat at the UN level, we must carefully design for it, and use the timing and available military assets to help bring issues to a higher level of decision making at the United Nations, Takemi argued. Policy makers who recognize infectious diseases as a threat to their own national security will understand their overall importance to the collective global and human security, he continued. He therefore endorsed the concept of security as an effective way to politicize the threat of infectious diseases and compel policy makers in the United Nations and WHO to take action.

Liu responded that, while she recognizes the need to create interest at the highest levels of global decision making, she did not want the issue of security to eclipse a “people-centered” response to infectious diseases. “Caring for patients or the community being infected is not a convenient side product,” she insisted. “The collective safety is actually the sum of the individual safety.”

While describing herself as one of WHO’s most ardent critics, Liu stated that she supported a leading role for the organization in responding to future infectious disease threats. “I think WHO has been a convenient scapegoat throughout [the Ebola] crisis,” she said. It is important to understand and learn from mistakes made in responding to Ebola—by MSF, as well as by WHO, she continued. Voicing her disappointment that the affected countries who endured the largest burden of the Ebola outbreak have not been better represented in these high-level discussions, she warned against one-way communications, whether they involve affected countries or communities.

Coordination of Stakeholders

What should be the role of a civil society organization? Gostin asked Liu. What are its responsibilities with regard to the UN institutions, among

others? Chris Elias of the Gates Foundation suggested that his organization failed to fully recognize and respond to the severity of Ebola in West Africa for many months because “in the absence of a clear framework for engaging nonstate actors, we weren’t engaged.” Noting that the standard ratio for NGO to in-country workers in the field is 1 to 10, Liu stressed the role of nonstate actors as trainers and mentors to a country’s health care workforce. Such training was particularly critical for Ebola in West Africa, she said, but it needs to go beyond responding to a single disease or health crisis. That is the challenge for global health governance: maintaining capacity and competence in every country to face the next outbreak, no matter what its cause.

Acknowledging the proliferation of such nonstate actors “with good intention, but very limited capacity and knowhow,” Liu suggested a response model based on the International Federation of the Red Cross: a trained pool of people, who could be called on in an emergency and organized through a larger command-and-control structure. Eduardo Gotuzzo of Universidad Peruaña Cayetano Heredia noted that civil society organizations can provide vital help in responding to national health emergencies—including infectious diseases with potential for international transmission—but that countries need to coordinate those efforts.

In West Africa, Liu reported, such coordination occurred, but it was inconsistent, highlighting an important governance issue when looking across a multinational geographic region: in one country, the minister of health led the response to Ebola; in another, it was the minister of defense; in some places, donor nations led the effort. Each of the three leadership structures had strengths and weaknesses that should be reviewed carefully for the lessons they can teach, she advised.

Information Sharing

Jennifer Gardy of the University of British Columbia highlighted the importance of data as a tool for addressing infectious disease threats, and the extreme difficulty many countries face in collecting epidemiologic data. Global health governance should involve stewardship of such data—and on related issues including culture, demography, climate, media use, and more, she argued. She proposed that a smartphone-based tool that facilitated data sharing would allow knowledge, rather than political agendas, to drive disease detection and intervention.

Progress made within existing governance structures could inform future efforts to address infectious diseases, according to Elias. For example, he said, efforts to eradicate polio, which had stagnated over the previous decade, have moved forward impressively over the past 3 years, due in part to a data-sharing agreement that allowed key partners in the polio

response to share data in real time. Another important factor was a strong command-and-control response to polio outbreaks, as occurred in Nigeria, Elias noted. Finally, echoing Liu’s point, he observed that the polio “end game” depended on community mobilization. Meeting community health needs more comprehensively has improved polio vaccination rates, helping the push toward eradication, he stated.

If any organization can overcome barriers to information sharing between states, nonstate actors, and industry, it is WHO, Chan insisted. In the case of polio, she noted, “I twisted a few arms, and we managed to get all the information we need.” Informal governance means “helping countries to understand the value they can bring to global health and not insulting them in public”—and by engaging government leaders without “naming, blaming, and shaming” them, she explained.

This page intentionally left blank.