Speakers and participants explored evidence on governance for global infectious disease control related to mechanisms for improved global health governance in this chapter on pieces of a governance framework at various levels. López-Acuña discussed the concept of global health security and the current alert and notification systems when a health emergency reaches pandemic levels, complemented by Jeremy Farrar of the Wellcome Trust who discussed challenges and opportunities for research in outbreak response. Speakers also gave perspectives on roles of the WHO regional offices, national governments, local humanitarian organizations, and the need and benefits of public–private partnerships in creating a holistic governance framework.

OVERVIEW OF GLOBAL HEALTH SECURITY

López-Acuña focused on the issue of global health security and the proposed collaboration by the UN humanitarian agencies and WHO in response to health emergencies with humanitarian impact. To clarify in discussions of terms like “global health security,” López-Acuña offered his own definitions and perspectives on a number of key concepts:

- Global health security is both the process and the outcome of keeping global health risks under control and ensuring the maintenance

-

of a “global health order.” Global health security encompasses alert and response to disturbances in this order, which can only occur through collective action and, therefore, depend on collaborative agreements at global, regional, and national levels. As such, the concept of global health security transcends the nation-state paradigm, but its process is intergovernmental in nature. Command-and-control models for attaining global health security contradict the notion of collaborative, intergovernmental action by nation-states, although it is possible to manage specific actions effectively using certain command-and-control elements. Linking the concept of global health security with that of national security is difficult, as individual member states’ positions may not align. Not all humanitarian emergencies have global health security implications, which argues against subsuming global health security within the humanitarian system.

- Global health risk is a term that has yet to be clearly defined. The International Health Regulations (IHR) 2005 define a public health risk as the likelihood of an event that may affect adversely the health of human populations, and especially one that may spread internationally or present a serious and direct danger. “This is vague from a public health perspective and weak in terms of linkages with humanitarian emergencies,” López-Acuña observed.

- Global health governance is implemented through the global health architecture, comprised of institutional arrangements focused on global health. A proliferation of entities, funds, mechanisms, and multistakeholder partnerships for global health over the past two decades have joined long-existing multilateral and bilateral structures to create a new global health landscape, characterized by parallel and sometimes duplicative objectives and governance structures.

- Global public goods for health are health interventions that require international collective action, such as those that ensure global health security. They should encompass global platforms and mechanisms to attain collectively agreed-upon objectives. A true global public good for ensuring health security would include collective responsibilities, action, financing, and accountability.

- A public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) as defined in the IHR 2005 is an extraordinary event that constitutes a public health risk to other states through the international spread of disease and that potentially requires a coordinated international response. López-Acuña also raised the question as to whether a sensitive and graded system should replace the all-or-nothing trigger represented by a PHEIC.

- A humanitarian emergency is an event or series of events that seriously threatens the health, safety, security, or well-being of a community or population. Populations vulnerable to such threats—those in which individuals or groups have a reduced capacity to resist and recover from life-threatening hazards—are most often poor. The United Nations’ consultative Humanitarian System-Wide Emergency Activation responds to major, sudden-onset humanitarian crises resulting from natural disasters or conflict. The decision to proceed with the activation is based on the scale, complexity, urgency, capacity, and reputational risk associated with a given event. A clear provision for humanitarian crises triggered by epidemics will need to be developed jointly by the humanitarian and the outbreak alert and response communities within the United Nations, López-Acuña observed.

Elias responded to López-Acuña’s conclusions that it is currently impossible to supersede the nation-state paradigm, that WHO should lead any global public good for ensuring health security, and that decisions regarding emergency alert and response should be informed by an independent advisory committee. With the possible exception of a new independent accountability mechanism, the framework for global health security proposed by López-Acuña strongly resembles the status quo, yet would take a long time to establish, Elias observed. He therefore expressed concern that the systemic constraints López-Acuña described would obstruct the path to truly effective change—the kind of change that could have made a difference in the response to Ebola in West Africa. Elias asked what might accelerate this effective change, given the outlined constraints, and López-Acuña suggested greater advocacy and resources for building national core capacities. Bilateral, multilateral, and foundation-based investments in core capacities would have the additional benefit of performance measurements, he added. Second, the accountability commission process could be designed to produce rapid feedback as a basis for action. Finally, he suggested, a structure for efficiently organizing international medical teams responding to both outbreaks and humanitarian emergencies could be established quickly by adapting existing platforms and scaling up.

Farrar observed that the global health community’s repeated calls—since the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic—for such obvious improvements as capacity building, enhancing health systems, and better training have gone largely unheeded. To continue to pursue “business as usual” to the extent recommended by López-Acuña is unacceptable, Farrar insisted. The currently diffuse governance structure for global health threats admits no accountability, he explained; authority and accountability need to reside within a single, transparent structure. Today,

he observed, “nobody is really sure who is carrying that responsibility, and as a result, nobody carries it.” Although the long-requested capacity building, training, and long-term investment are undeniably needed, if that is all the change that is demanded, once again nothing will change, he argued.

The Alert System

To ensure health security, WHO should be leading any health interventions in the name of global public good, López-Acuña stated, and the WHO Director-General, in close consultation with member states and advised by an independent scientific committee (appointed by the United Nations’ Executive Board, not by the WHO secretariat), should make all relevant decisions. Upon declaration of an alert, relevant action should be primarily implemented through national health authorities in the affected countries in collaboration with WHO, he said. Where health systems are fragile, response can involve a health coalition led by WHO and may also entail a humanitarian response that engages relevant nonstate actors. If necessary, civil or military assets standing by in established locations worldwide can be mobilized as well. An independent accountability commission, authorized by the UN Executive Board, should oversee this response, which cannot be appropriately managed through command and control, he concluded.

A global alert system cannot ensure global health security until every country attains the IHR-mandated core capacities, López-Acuña insisted. Sanctions should also be imposed on countries that hide information about health threats within their borders, he added. The system must provide reliable information for decision making and swift action, and it should incorporate advanced information and communications technology. The current global response system is the weakest component of what is needed to ensure health security, which clearly represents a vital need and a global public good, according to López-Acuña. Its shortcomings were apparent during the Ebola crisis, during which the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) effectively mobilized expert epidemiologic capacity, but not the international clinical care teams that were needed to compensate for inadequate core capacities in the affected countries. A coordinating mechanism that mobilizes appropriate clinical teams from member states could build a more comprehensive global health workforce, he observed.

Institutional capacity for multihazard emergency preparedness and response systems must be developed at national, regional, and local levels within every country, López-Acuña declared. This process will take decades, he predicted, as it encompasses capacity building, financial sustainability, and infrastructure strengthening. Each country’s emergency preparedness and response systems should be aligned with structures that fulfill national responsibilities under the IHR, he added. While the United Nations’ human-

itarian response system and WHO’s IHR-related alert and response system should be prepared to recognize and act on the subset of health emergencies that require their coordinated efforts, each system must maintain its distinct objective and governance mechanisms, López-Acuña stated. A dedicated coordination platform could ensure the international interoperability of both systems when collaboration is necessary, he suggested. Additional measures to support a coordinated response to health and humanitarian emergencies would include more active engagement of the UNISDR in the prevention and mitigation of global health risks as part of its preparedeness agenda, and the mainstreaming of actions to address global health risks in the UN Development Assistance Framework, he noted.

Notification of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern

In conclusion, López-Acuña asserted, it is possible to enable global public good for ensuring health security from basic elements of the existing health and humanitarian response architecture. Enhanced by greater interconnectedness, these elements could remain situated within the parameters of the current WHO but have improved systems performance. Because the designation of a PHEIC and the associated responses can be delayed due to a multitude of factors and generate challenges because of travel and trade implications, among other issues, López-Acuña suggested replacing the current notification system with a phased international response strategy. This phased approach would be based on the magnitude of a given health threat and the appropriate governance of its response.

- Phase I: Emergency with a health impact; response led by WHO together with member states.

- Phase II: Health emergency with humanitarian implications; response jointly led by WHO and the UN Emergency Relief Coordinator/ Inter-Agency Standing Committee (ERC/IASC).

- Phase III: Health emergency with implications for global security; response led by the UN Secretary-General, in close collaboration with WHO and with support from the UN Security Council and ERC/IASC.

Not all PHEICs create humanitarian emergencies, nor do all outbreaks represent a threat to global health security. Some outbreaks can and should be managed by national, regional, and global health sector mechanisms and platforms within the framework of the IHR 2005, López-Acuña said, provided the stipulated core capacities are in place. However, disease outbreaks that overwhelm national capacities can create humanitarian crises that require an international response; these events, he argued, ought to be

considered humanitarian emergencies. It is only for the relatively few outbreaks that have an international impact as well as a humanitarian dimension that WHO’s outbreak alert and response and the United Nations’ humanitarian systems must collaborate.

Embedding Research and Development

Farrar observed that the glut of meetings that have followed each major epidemic over the past two decades have done little more than rewrite history as the horrors of the experiences faded away. Meanwhile, infectious disease dynamics have continued to change, with social factors increasingly driving transmission. Reiterating previous comments of applying retrospective solutions to future unknown epidemics, he declared that effective preparation will require a broad spectrum of research, encompassing clinical studies, disease mapping and modeling, epidemiology, biomedical research, and social sciences such as anthropology and ethics.

The most challenging—and potentially rewarding—aspect of conducting this ambitious program of research is its context within the chaos of unfolding epidemics. Speaking from his own experiences, Farrar added, there is a responsibility to do something called research, however that may be defined. This tension between response and research is magnified by the fact that the two activities tend to be siloed, and that the research community itself is highly specialized, he noted. Thus, he stressed, it is important to remember that research—implemented as policy and practice—can save lives and needs to be incorporated into the response (Farrar, 2014).

Unfortunately, the life-saving potential of research has remained largely untapped in recent epidemics of Nipah, SARS, enteroviruses, H5N1, H1N1, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus, and Ebola, Farrar pointed out. Ebola may be the first emerging infectious disease for which a safe and effective vaccine is developed; by contrast, influenza vaccines are unacceptably ineffective and avian influenza vaccines largely nonexistent, he noted. Similarly, it remains to be determined whether antiviral treatment saves lives or prevents secondary transmission of the influenza virus, arguably the most devastating global health threat and the cause of a 2009 pandemic to which one-sixth of the world’s population was exposed. Farrar noted that the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium,1 an effort under way by the Heads of International Research Organizations (HIRO),2 is developing universal research proto-

___________________

1 See https://isaric.tghn.org (accessed January 8, 2016).

2 HIRO includes representatives of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the European Union, the Wellcome Trust, the UK Medical Research Council, and other organizations from Canada, China, India, and South Africa.

cols for use during epidemics and attempting to resolve associated consent and ethical issues beforehand. Findings from studies conducted during outbreaks must be integrated with and supported by equally vital research conducted between epidemics, he added.

Any discussion about global health governance must include provisions for research, Farrar insisted. The ethics of research approaches should be debated in civil society in order to ensure that the voices of patients and affected populations are heard by the many and often dissociated actors who may implement research protocols during an epidemic, he advised. Mutual understanding among these disparate communities can provide a basis for conducting studies that saves lives, he observed. Duchin asked Farrar if governance for the research activities he proposed should be integrated into an overall global health governance structure or if it should involve a separate system. Ideally, Farrar replied, research would be governed as an integral part of the global health structure and system, albeit through different expertise than would be needed to govern emergency response. Such a structure is needed to counteract specialization and encourage collaboration between such seemingly aligned disciplines as public health and clinical medicine, as well as between the long-separated animal and human health communities, he noted. Training—although currently a cause of “siloing”—could also promote greater understanding between the various health communities, he added.

Gotuzzo of Universidad Peruaña Cayetano Heredia and Daszak of EcoHealth Alliance emphasized the importance of research on zoonotic diseases, and particularly diseases of wildlife, due to their predominance among emerging disease threats. Fineberg suggested that a “real-time learning officer” could be charged with ensuring that research protocols were effectively implemented during an epidemic. Kimball of Chatham House extended this hypothetical position to address the need for better record keeping during epidemics, which in turn would help plan research to be conducted in future outbreaks. Perhaps this research officer could be “multivalent,” she said—capable of facilitating randomized controlled trials for drugs and vaccines, but also able to design and direct the “bare minimum” of clinical research to describe protocols and outcomes during an epidemic.

The upstream establishment of guidelines and frameworks for research in advance of an epidemic would make a “huge difference” to improving the collection of vital information, Liu of Médecins Sans Frontières observed. Just as evidence-based algorithms for clinical care save lives, algorithms for conducting research during a chaotic epidemic response can ensure that information leading to improved practices is collected without compromising care—and, thereby, that even more lives are saved. Research for improving epidemic response should extend beyond the clinic to examine the entire spectrum, including nonhealth sectors, advised Kumanan

Rasanathan, senior health specialist at UNICEF. He suggested two practical considerations worthy of study: the role of the community health worker and the utility of community mobilization and health literacy messages. “There will always be great uncertainty during emergencies, and yet decisions need to be made,” Relman of Stanford University observed. How should governance at all levels address and communicate uncertainty in a scientifically appropriate way? Farrar replied that learning how to communicate uncertainty and being comfortable with that is absolutely critical.

Along with algorithms and procedures for research in the context of an epidemic, it will also be important to build regional or local capacity for conducting these studies, as well as greater public awareness about research, stated Margaret Hamburg, former commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. This will support important research in neglected areas of public health and medical care, build capacity for basic health care, and facilitate the ability to conduct clinical trials and other studies in the context of an emergency, she pointed out. “It’s very tragic if we go through something like a pandemic or an Ebola event without learning whether certain proposed therapies actually work or harm people,” said Jesse Goodman of Georgetown University. Well-prepared protocols and advance resolution of ethical issues represent an important part of public health infrastructure, he added, and he noted that the U.S. Institute of Medicine is likely to undertake a deep examination of the subject of health research during emergencies. There are many barriers to action, Farrar acknowledged, “but we shouldn’t forget the ethics of inaction.”

WHO REGIONAL OFFICE ROLES

Claude de Ville de Goyet, consultant to the United Nations and former director of emergency preparedness for the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), discussed governance for health emergencies on the part of WHO regional offices. Goyet urged participants to consider the ways this structure benefits member states and their populations in general, beyond the context of the Ebola crisis. Conflicts that arose between WHO headquarters (HQ) and the Regional Office for Africa (AFRO) in that crisis were longstanding, he suggested, and particular to that region. But conversely, the sharing of power between HQ and other regional offices, while sometimes difficult, had not impeded the management of the H5N1 influenza pandemic, nor that of SARS.

AFRO has a serious governance problem, Goyet declared, but he did not know if the problem was due to structure, implementation, or regional autonomy. In contrast to AFRO, PAHO is “respected for its level of health governance,” Goyet observed. He offered several reasons for this, including PAHO’s original purpose of controlling yellow fever and other infectious

diseases, and its comparatively high level of funding. PAHO entered the realm of regional governance for disaster preparation in 1977, following an earthquake in Guatemala. Since then, the office has taken an all-hazards approach to emergency response, emphasizing mutual assistance between states and cooperation across borders and among subregional disaster management organizations, he said. Most WHO regions have adopted an all-hazards response approach resembling PAHO’s, which emphasizes preparedness and proactive, on-site coordination.

As previously noted, the United Nations’ response to humanitarian crises is organized according to nine thematic clusters, each led by a UN agency such as UNICEF, WHO, and the World Food Programme (WFP). Most countries engage with the clusters as a way to strengthen their ministries of health and promote local governance—a trend that reflects a beneficial balance, Goyet asserted: emergency funding should be limited as compared with funding for strengthening capacity. A good example of partnership between countries and the UN clusters is the Foreign Medical Teams (FMT) Initiative,3 he observed. Established by the Global Health Cluster, the FMT Initiative coordinates the assistance of medical teams during health emergencies, employing a model developed for earthquake response. Its success shows that health governance for outbreaks requires adaptation, not reinvention, he said. The WHO HQ and regional offices should play distinct roles in a health emergency, according to Goyet, who offered a side-by-side summary (see Box 6-1). With regard to the final point around maintenance of public health programs, Goyet speculated that the fear-driven shifting of resources for basic health care to Ebola control may have cost more African lives than it saved. Liu pointed out that the significant challenge of infection control in health care centers—which became Ebola amplification centers at the height of the epidemic—frequently forced their closure. Both agreed that this gap in care should be addressed in planning for future events of this scale.

Responding to Goyet’s remarks, Kapila of the University of Manchester asserted that the region is not the cumbersome and outmoded level of governance that some have suggested, but instead is increasingly represented in the United Nations and other organizations. WHO must make a virtue of its regional offices because they are owned and loved by member states, he advised. Goyet suggested that the trend is not so much toward regionalization as toward subregionalization, in the form of subregional health and

___________________

3 Recognizing that uncoordinated medical team deployment can disrupt national emergency coordination plans, the United Nations’ Global Health Cluster established the FMT Initiative, a global mechanism to assist governments with the coordination of medical teams during public health emergencies. See https://extranet.who.int/fmt/page/about-us (accessed January 8, 2016).

disaster management institutions, but that these need support from above, as well as a common voice at the global level. Regionalization is a must because WHO is not a homogeneous organization, stated Ron St. John, currently a consultant to WHO. Regional structures enable cohesiveness among countries and, in turn, can be linked to create a global entity that nonetheless reflects diversity, he added.

ROLE OF NATIONAL-LEVEL GOVERNANCE

As a preface to his discussion of governance for health emergencies and the provision of WHO assistance at the national level, St. John asserted that WHO must retain its global authority but is ripe for fundamental change. Expressing his disdain for the term “command and control,” St. John instead embraced the term “management” and noted that command and control merely describes the management of time, resources, and information. This was his task as an emergency manager in Canada during events that included the repercussions of 9/11 and the anthrax mailings, SARS, Hurricane Katrina, and several natural disasters. These experiences taught him that even minor emergencies are at least initially chaotic, and that gaining and keeping the trust of affected populations and communities is essential to effective emergency management. He also confronted the unfortunate reality that the massive costs of emergency response dwarf what is generally spent on emergency preparedness in the form of planning and training—reinforcing earlier calls for attention to health capacity building, which can create a more prepared health system and community.

Establishing Incident Management Systems

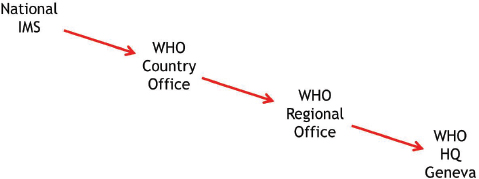

Typically, local first responders to any emergency manage it on their own unless and until their capacities are exceeded, St. John observed. At this point an emergency management framework should be activated, engaging local, state/provincial, and national governance levels, with information and requests for assistance flowing from lower toward higher governance levels, and resources flowing in the opposite direction. Ideally, a multidisciplinary team would convene at an emergency operations center—perhaps within a single room—to manage incident response. These activities comprise an Incident Management System.

In reality, capacities for managing health emergencies vary widely among countries, and among their local and state/provincial agencies, St. John noted. Information sharing and coordination is often weak between governmental levels in the health sector, as is planning for necessary surge capacity, he said. The concept of the emergency operations center tends to be limited to the national security sector and less applicable to public health responses. The health sector understands the application of the Incident Management System to disasters such as earthquakes, but not to epidemics, according to St. John. Political and economic disincentives to reporting an outbreak present significant barriers to implementing the Incident Management System, he observed, but he presented the use of an Incident Management Framework, assuming all levels are operational and national capacity has been exceeded (see Figure 6-1). Moreover, as compared with

SOURCE: St. John Presentation, September 2, 2015.

acute disasters, epidemics are fraught with uncertainty as to their transmission dynamics, severity, and duration—characteristics which also contribute to the “fear factor” mentioned by Goyet—highlighting Farrar’s previous comments about the critical need to be able to successfully communicate elements of uncertainty to the public during an outbreak.

“I believe the Incident Management System can be adapted to any complex health emergency, even in WHO,” St. John stated. He pointed to elements of an Incident Management System for outbreaks already present within WHO, for which PAHO’s successful Ebola emergency operations center could serve as a model. Every WHO country office should have a designated, trained incident manager, he proposed—a role that he estimated would require about 100 full- or part-time positions worldwide. Flexible, scalable plans for activating an Incident Management System and providing surge capacity must also be put in place, he said. In a complex health emergency, such as occurred during the SARS outbreak, the WHO-led Incident Management System within the health sector should coordinate with Incident Management Systems in other groups and other sectors, he advised. Ben Anyene of the Health Reform Foundation of Nigeria cautioned that the Incident Management System, as it currently exists, does not adequately integrate nonstate actors that increasingly contribute to emergency response efforts. Nonstate actors tend not to be represented at emergency operations centers, he observed, and yet they perform a variety of functions that others cannot. He advocated for including them in the overall system and any type of operations center.

Duchin observed that the Incident Management System features several elements of good governance as previously discussed (e.g., flexibility, scal-

ability, and ability to incorporate at global, regional, and local levels) and therefore could provide a model for a governance framework. Fleshing out this structure would require integrating input from a variety of different stakeholders, creating a communication structure, and making provisions for decision making, logistics, and functionality, he continued. It would also need to be accompanied by guidance on appropriate training for development of these types of systems.

ROLE OF LOCAL HUMANITARIAN ORGANIZATIONS

Ben Anyene is leader and founding member of the Health Reform Foundation of Nigeria,4 which works within the contexts of national, state, and local health governance in that country. Illustrating the point made by Stocking and others that the lack of basic health care constitutes an actual and ongoing health crisis for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), Anyene reported that, each year in Nigeria, more than 50,000 women die in childbirth, and 1 million children under 5 years of age die from preventable diseases. “Why shouldn’t we be responding to this health care crisis, rather than waiting for the next big disease outbreak?” he asked.

In Nigeria, as in most LMICs, frameworks for emergency preparedness and response, if they exist at all, are limited to the deployment of relief materials such as food and blankets after a crisis has occurred, Anyene reported. “Most response activities by nonstate actors during a disease outbreak and other health crises are often those of ad hoc and unregulated arrangements with adverse consequences,” he added. This situation is unlikely to change unless politicians, and the business interests that control them, recognize the economic benefits of emergency preparedness, he said.

Despite the strain placed on Nigeria’s weak health care system by a variety of diseases and civil disputes, it is slowly improving, Anyene reported. Quality health care in Nigeria is largely privatized and not affordable to the vast majority of citizens, so community-based and faith-based organizations attempt to fill this gap, supported by a culture that traditionally values extended family and community solidarity, he observed. When health crises overwhelm local responders, agencies such as the Nigerian Centre for Disease Control, the Nigerian Emergency Management Agency, the Nigerian Red Cross, and the Nigerian arm of the International First Aid Society may be engaged, but there is no governance structure in place to organize their activities. Even so, he noted, containment of the recent Nigerian Ebola outbreak occurred through the coordinated efforts of different levels of government and international partners, and featured emergency

___________________

4 See http://www.herfon.org.

operation centers, good contact tracing, and incident case management. The same could be said for Mali and Senegal, he added.

Further strengthening of health emergency response capacities should involve the creation of accountability frameworks to encourage “effective synergy” among relevant government agencies and local and international organizations, Anyene advised. He also suggested that training in health emergency response become part of Nigeria’s mandatory civic education program, which includes a year of service in the country’s National Youth Service Corps, and that similar training be extended to local humanitarian organizations.

The impact of Ebola in West Africa demonstrates the need for LMICs to build their own capacity and governance for responding to health emergencies and, thus, cease to depend upon international intervention, Anyene concluded. Response efforts at national and subnational levels should be guided by principles of humanitarian assistance, he added, and directed toward solving immediate problems, implementing evidence-based interventions, strengthening health systems, and creating value for money.

ROLE OF PUBLIC–PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS

Rebecca Marmot of Unilever discussed how her company and the private sector in general have responded to both ongoing health crises and health emergencies such as the West African Ebola epidemic. As one of the world’s largest companies, Unilever produces foods and goods for home and personal care that reach markets around the world. Unilever’s business strategy recognizes the following key environmental factors, according to Marmot: climate change and associated weather extremes (e.g., flooding and drought); volatile political situations, leading to increased human migration; and the nutritional “double burden” of hunger in some places and obesity (and its attendant pathology) in others. Along with other private-sector players, Unilever is developing strategies to serve corresponding needs in communities around the world, and to work more efficiently with the public sector—particularly the health sector—in meeting these challenges, she said.

Through its Sustainable Living Plan, Unilever aims simultaneously to expand its business and make a positive global impact, Marmot stated. The targets for this plan are informed by the United Nations’ Millenium Development Goals5 and Sustainable Development Goals.6Unilever’s disaster and emergency response strategy is embedded within this more general

___________________

5 See http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/goals (accessed December 18, 2015).

6 See http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals (accessed January 8, 2016).

plan, Marmot explained. In addition to costing the company more than $300 million per year, disasters exact an inestimable toll on their customers and the communities in which they live, she said, with the Ebola crisis further focusing efforts by the company to refine its response to such events. Addressing the three pillars of preparedness, relief, and rehabilitation, Unilever aims to maximize positive impact on communities while minimizing the business impact of disaster. The company’s preparedness activities include training farmers in climate-resilient practices and their employees in disaster preparedness, as well as planning to ensure continuity in supply chains and logistics. Unilever also seeks to support relief efforts with appropriate products, such as soap, detergents, emergency sanitation packs, and fortified foods acceptable to the affected population.

Noting that rehabilitation “is probably the area where the private sector has the biggest opportunity to make a positive impact,” Marmot said she hoped to gain insight on ways that her company and others could better support the rebuilding of communities and economies. “When communities are displaced or impacted by health crises or by pandemics, by disasters, they are not waiting for a handout,” she observed. “They are desperate to get back on their feet as quickly and efficiently as possible, to get schools open, to get commerce up and running, to be able to get supplies back into the communities where they are most needed.” Marmot shared the principles that form the foundation of Unilever’s emergency response strategy (see Box 6-2).

“Unilever has a fairly sizable presence in West Africa, particularly in Nigeria,” Marmot noted, explaining, “when the Ebola crisis started to unfold, we, like many others, were slow in our response.” Eventually they turned to their three-tiered approach. Their efforts included partnering with NGOs such as Save the Children, donating their products, offering the services of their distribution and supply chain teams to plan logistics, and training responders in behavior change techniques to help them address the many social challenges they faced, she said.

Unilever’s intent—and that, presumably, of the many private-sector organizations that responded to the Ebola crisis—was not to solve it, but to contribute the “private-sector mindset” to efforts by NGOs and government responders, Marmot explained. Unfortunately, she added, there was confusion and disarray about how private-sector partners should approach the situation: whether to work with existing partners in the United Nations, or directly with the governments of affected countries, or to go through WHO? She described how complicated it can be to understand the optimal way for the private sector to contribute value to a response.

Unilever also seeks better alignment with the UN cluster system in anticipation of future health emergencies, said Marmot. In general, the private sector wants to know how to be useful to health emergency response

efforts, whether it involves skills, expertise, product development, or devising new governance models. The private sector also wants to understand limitations, as well as opportunities, for involvement in efforts to address global health emergencies, she stated. Unilever has played a role in developing the Sustainable Development Goals and hopes to contribute to developing the Global Health Risk Framework as a model for emergency response to be developed and tested before the next crisis strikes. For such a framework to succeed, she concluded, “business and the NGO community and UN and civil society will need to interact even more than they have done before.”

Kimball asked the public-sector speakers to reflect on their experiences working with the private sector in response to health emergencies. Goyet characterized his experiences as short-term responses to emergencies of variable quality, saying that in order to avoid conflicts of interest, he had not accepted donations from the private sector, only expertise. The private sector is both ubiquitous and a resource, Anyene observed; the various concerns about its involvement in emergency response could be addressed

in the design of the Global Health Risk Framework and made specific to individual companies through transparent formal agreements, he suggested.

Kimball wondered why business service organizations, such as Rotary International, are not the primary conduit for business involvement in emergency response, since that would remove the possibility of competitive advantage for any one company. Marmot stressed that the possible contributions companies can make to a recovery effort extend well beyond those that might appear to boost their sales and, most significantly, would involve the use of their expertise in solving complex problems associated with emergency response. Unilever’s participation in multisectoral efforts to effect systemic change, such as the World Economic Forum, is another way the company engages with civil society for the common good, she added.