This chapter outlines four different potential models of global governance for health risks in terms of their underlying assumptions and their strengths and weaknesses, analyzed by various speakers and participants. “These four models are simplified, and they are in many ways oversimplified, but sometimes there is clarity in oversimplification,” explained Gostin. He also noted that these models are neither mutually exclusive nor exhaustive of all possibilities for global health governance. The model presentations were followed first by comments from a three-person reactor panel, then by a general discussion.

MODEL 1: A REFORMED WHO

“The case for reforming WHO does not just rest on its supposed failures in relation to emergency response, but rather, most reform proposals over the past two decades have focused on improving the effectiveness of the WHO’s technical and normative work.”

—Charles Clift, Chatham House

Clift described a model based on the Chatham House report he discussed in Chapter 5. WHO’s performance during the Ebola crisis—although it unfolded after the Chatham House report was prepared—highlighted problems in its organizational structure, governance, and culture. He thought that WHO’s role in disease outbreaks should not be examined in isolation from its normative functions, but instead urged the audience to consider how much of WHO’s resources should be devoted to outbreak response. To introduce the model, Clift outlined the following assumptions behind it:

- Reforming WHO would address the main reasons that the Ebola response was unsatisfactory.

- Reforming WHO is necessary if the “structural causes of any shortcomings,” as noted in the report of the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel, are to be corrected.

- “Business as usual” or “more of the same” is not an option, as noted in the report of the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel.

- The member states of WHO have an appetite for its fundamental reform.1

Clift then presented a series of reform proposals in several key areas. The first involved the insulation of WHO’s technical work from its political interests, based on the assumption that the excessive intrusion of political considerations in WHO’s technical work damages WHO’s credibility. To meet this challenge, the Chatham House panel advised that WHO should provide for a clear distinction between its technical departments and those dealing with governance by appointing a Deputy Director-General with responsibility for technical work and its integrity, akin to the role played by Chief Scientists in UK government departments. In addition, the panel echoed previous suggestions that the position of WHO Director-General be limited to a single 7-year term. Second, based on the assumption that WHO’s structure of elected regional directors constrains its effectiveness in both its “normal” work and its disease outbreak response capabilities, the panel offered the following alternative proposals

- A unitary model, in which WHO, like other UN organizations, determines the need for regional and country offices on the basis of operational requirements, and in which regional directors are appointed directly by the Director-General; and

- A decentralized model, like that of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), with regional offices that are directly funded by member states, rather than indirectly via their assessed WHO contribution.2

___________________

1 Upon introducing this assumption to the workshop, Clift added, “The hypothesis is they probably don’t, but discuss.”

2 Under this alternative, Clift acknowledged, “some regional offices might not survive. That may or may not be a good thing, depending on your point of view.” He also noted that some regional offices could align with existing regional organizations, such as the African Union, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. “Many different organizations that have grown up organically in the regions could be used to fulfill some of the health functions of WHO regional offices,” he observed.

Furthermore, the Chatham House panel assumed that WHO’s 150 country and 6 regional offices are superfluous, that some are either too large or too small, and that not all are staffed appropriately to local needs (as demonstrated by the Ebola crisis), Clift reported. They therefore proposed the following reforms:

- A comprehensive and independent review3 intended to match the staff profile of country offices to their host countries’ needs, and

- An internal review of the mix of skills and expertise of country and regional office staff to ensure that these fit with its core functions and leadership priorities.

On the subject of finance, the Chatham House panel assumed that reform is necessary in order to persuade member states to support stable funding arrangements to fulfill WHO’s core functions, including responding to disease outbreaks, Clift stated. Clarifying that this does not necessarily mean providing more money overall, he pointed out that WHO’s administration and management costs could be substantially reduced as a result of reforms to regional and country offices, which currently consume more than 60 percent of the organization’s budget. Clift suggested that “one reason why member states are very reluctant to increase their contributions is that they don’t trust the organization to do what it says.” Thus, the panel recommended that WHO and its member states examine how to enhance their effectiveness by increasing value added by regional and country offices, and reducing administrative and management costs. He concluded that the same level of work could be done with fewer people with the right skill set, but acknowledged that people are reluctant to tackle that as an issue.

WHO will only change if charged to do so by its member states, Clift insisted. Thus, he said, a bargain must be made in which the states encourage more courageous reform actions on the part of the organization, while also offering the incentive of more stable funding for WHO’s core functions, including outbreak response.

MODEL 2: WHO PLUS

As Stocking had previously described, the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel she chaired proposed the creation of a center for humanitarian and outbreak management attached to WHO and under authority of the Director-General that combined strategic, operational, and tactical func-

___________________

3 This was suggested by WHO’s Executive Board in 1997, and subsequently in external reports from the joint intelligence unit of the United Nations and other evaluators, but was never undertaken, Clift pointed out.

tions. A member of that panel, Ilona Kickbusch of the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, Switzerland, offered remarks informed by the panel’s work, as well as by her own views. Kickbusch emphasized that any model would oversimplify the complex system involved in global health governance for infectious diseases, warning that any changes made in one part of the system will impact another part. Therefore, the panel attempted to target changes that would produce a positive system-wide dynamic and avoid destructive effects.

“Most countries have a responsibility in their constitutions to protect their peoples, as does the European Union. Health security is sort of the global public health side of things, combined with universal health coverage.”

—Ilona Kickbusch, Graduate Institute of International and

Development Studies, Geneva, Switzerland

The Ebola Interim Assessment Panel’s recommendations are based on several assumptions, which Kickbusch described. The first and foremost of these was the declaration by WHO’s member states that the responsibility for health security rests with the organization, which should be strengthened to fulfill this core function. While differing from the Chatham House panel in the suggestion not to separate the technical and political functions of WHO, the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel felt both elements needed to be better managed at the level of the member states, as well as within the secretariat, Kickbusch stated. Having been “disappointed [and] infuriated” by the World Health Assembly’s (WHA’s) rejection of a 5 percent increase in assessed contributions that would have provided for such strengthening, the panel proposed that this measure be reintroduced, she reported.

The Ebola Interim Assessment Panel’s proposed center for humanitarian and outbreak management attached to WHO would bring together emergency, humanitarian, and International Health Regulations (IHR) functions, Kickbusch explained, and it would work in two modes. In the “everyday” mode, the center would monitor and support the control of limited outbreaks and, especially, facilitate outbreak preparedness through simulation and workforce training as is currently performed in the security sector. The shift into “crisis” or “command-and-control” mode would be initiated by a specific mechanism. Both modes, and the transition between them, would be governed by the center’s director, in consultation with the WHO Director-General, and guided by an advisory board in such a way as to create transparency and ensure effectiveness.

“This system has to be able to respond quickly to very, very different kinds of outbreaks and emergencies,” Kickbusch advised. “There are things

about the next crisis we are not going to be prepared for, but we have got to be able to adjust much more quickly and have much more accountability and transparency in relation to what is happening.” In order to support this activity, she called for an increased health security budget within WHO as well as an increased political commitment from member states.

The Ebola Interim Assessment Panel largely agreed with the recommendations of the Chatham House report with regard to the role of the WHO regions, country offices, and the representatives to the WHA, according to Kickbusch. She noted that staffing needs to be country and region appropriate, and there should be a prioritized and costed plan for all WHO functions. In considering the IHR, the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel embraced the underlying concept of “pooled sovereignty,” Kickbusch stated. On that basis they concluded that compliance requires peer review rather than self-assessment, a notion that she reported is now more acceptable to member states than it once was. Relatedly, peer review, along with various incentives, disincentives, and sanctions, is currently being discussed by WHO’s IHR Review Committee. Because a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) is “something we all want to avoid,” there should be intermediate measures available, as well as more transparent decision-making processes along the way.

The proposed WHO center for humanitarian and outbreak management is intended as a “global space of responsibility,” Kickbusch said. Recognizing the typical separation—and sometimes competition—between the priorities of health security and universal health coverage, she advanced the view of health security as human and social security. WHO, she added, has tended to keep these agendas separate, and that must change, as many including Chan have acknowledged. Reforming WHO according to the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel’s recommendations will require the highest political commitment, extending well beyond the health sector, Kickbusch asserted, specifically adding that they are looking to the UN high-level panel to work on political and funding support of WHO.

MODEL 3: AN EXECUTIVE AGENCY

“The executive agency model is activated only when a multisectoral global response is required to reduce health risk. This allows the UN system to create an enabling environment in which WHO takes the lead in the health sector or cluster.”

—Yasushi Katsuma, Waseda University, Japan

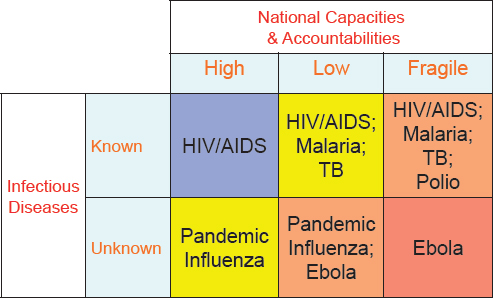

NOTE: TB = tuberculosis.

SOURCE: Katsuma presentation, September 2, 2015.

Yasushi Katsuma of Waseda University, Japan, presented a model in which WHO, hosted by the UN Secretary-General, executes a strategic operational and tactical role in a health emergency. As Gostin noted, this model aims to take advantage of WHO’s expertise and legitimacy, while tapping into the UN’s higher-level political authority and support.

To provide context for the executive agency model, Katsuma described a typology of health risk as a matrix defined by two variables: infectious diseases that are either known or unknown, and national capacities and accountabilities for outbreak response that are high, low, or fragile (see Figure 7-1). Thus, he explained, a known infectious disease like HIV/AIDS represents a different risk in the United Kingdom, where national capacities and accountability for response are high, than in Somalia, a fragile state. This matrix, in turn, defines four different types of health risks and appropriate responses, which he characterized as follows:

- Type 1: when the infectious disease is known and the national capacities are high. Governments of such countries may not need support from WHO.

- Type 2: when the infectious disease is known and the national capacities are low; or, when the infectious disease is unknown and

-

the national capacities are high. In these cases, WHO must respond at the international level, but within its typical capacity, including engagement and communication efforts.

- Type 3: when the infectious disease is known and the national capacities are fragile; or, when the infectious disease is unknown and the national capacities are low. These cases require a multisectoral development response within the UN Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF), with WHO taking the lead in the health sector.4

- Type 4: when the infectious disease is unknown and national capacities are fragile(e.g., the initial months of the Ebola epidemic in West Africa). This situation requires a multisectoral humanitarian response by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), with WHO taking the lead in the Health Cluster.

The proposed executive agency model is activated only when a multisectoral global response is required to reduce health risk, as in Type 3 and Type 4, Katsuma stated. This allows the UN system to create an enabling environment in which WHO takes the lead in the health sector or cluster. For a Type 3 risk, at the global level, response would involve the UN Development Group, including the World Bank Group, chaired by a UN Development Programme (UNDP) administrator, with the active participation of WHO, he explained. At the regional level, greater harmonization would be needed between the WHO regional offices and the regional offices of UN programs and funds such as the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), UNDP, and other agencies, he observed. The country-level response to a Type 3 risk involves a UN team headed by a UN resident coordinator who is familiar with local health issues, along with the UNDAF, in which WHO takes the lead in the health sector.

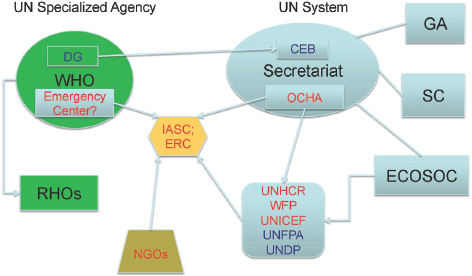

For Type 4 risks, the most complex and demanding, the executive agency model stipulates a global-level response involving the WHO Director-General, as a member of the UN Chief Executives Board, working closely with the UN Secretary-General, Katsuma said (see Figure 7-2 for mapping of global response). The UN Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) would harmonize the humanitarian work of UN programs and funds, the UN specialized agencies including WHO, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and other responders, he added. OCHA—headed by an emergency relief coordinator in a humanitarian crisis—would activate the resources of the UN Central Emergency Response Fund. This, too,

___________________

4 Based on his extensive experience in the UN system, Katsuma observed that the UN response to such Type 3 health risks “seems to be working quite well,” so he characterized these situations as “business unusual, but I think we don’t have to worry too much about it.”

NOTE: CEB = UN System Chief Executives Board for Coordination; DG = WHO Director-General; ECOSOC = UN Economic and Social Council; ERC = Emergency Relief Coordinator (head of OCHA); GA = UN General Assembly; IASC = Inter-Agency Standing Committee; OCHA = UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs; RHO = regional health organization; SC = UN Secretary-General; UNDP = UN Development Programme; UNFPA = United Nations Population Fund; UNHCR = United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; UNICEF = United Nations Children’s Fund; WFP = World Food Programme.

SOURCE: Katsuma presentation, September 2, 2015.

could be a recipient of the possible World Bank pandemic emergency facility, as previously discussed.

The regional response to a Type 4 health risk, according to the executive agency model, would harmonize the regional health organization and the regional office of UN programs and funds—a process that Katsuma described as practically necessary, but politically difficult, due to the mismatch between WHO’s regions and those of the UN humanitarian system. At the country level, a UN team headed by a UN humanitarian coordinator familiar with local health issues would again be optimal, he said. Emergency planning would occur in the context of the UN Consolidated Appeals Process, in which WHO takes the lead in the Health Cluster; the same would occur in a multisectoral humanitarian response by OCHA, he noted.

Several challenges are presented by the Type 4 health risk response

described above, Katsuma noted. At the global level, the WHO’s proposed emergency preparedness and response center would need to be coordinated with UN programs and funds within the framework of OCHA, but that option does not seem to be currently under discussion, he observed, nor is there a provision for harmonization with NGOs within the framework of the IASC. OCHA would also need to increase staff members trained to respond to complex health/humanitarian emergency situations, he said. Capacities of regional health organizations would need to be enhanced for health emergency preparedness and response, and the aforementioned harmonizing of WHO’s regional offices and those of the United Nations’ humanitarian programs and funds would need to take place, he continued. At the country level, WHO or the relevant regional health organization would need to develop a health emergency team that could be dispatched quickly to an affected country and work as part of the UN country team.

It often happens that a UN mission comes to a country and attempts to bypass the UN country team, Katsuma observed. Instead, the UN humanitarian coordinator appointed to lead the UN country team should be familiar with local health issues. This, he acknowledged, would be a difficult position to fill, because the typical person in that position would often be involved in development programs, not humanitarian aid. Therefore, it may be necessary during a health emergency for the UN to replace an incumbent resident coordinator with a humanitarian coordinator who is better prepared to lead in a complex health humanitarian situation, he said.

MODEL 4: A SEPARATE AGENCY

“The real question I think we need to pose is whether it’s a governance issue requiring a new entity—or if it’s a problem of systems coherence, a problem of leadership at all levels, and a problem of coordinating the existing infrastructure and arrangements.”

—Daniel López-Acuña, Former WHO

Senior Adviser to the Director-General

The final model envisions an independent, interagency entity for global health risk governance, under the authority of the UN Secretary-General. Its presenter, López-Acuña, announced from the outset that he did not support this approach, but had offered to describe its advantages and disadvantages, which reveal established systems and capacities far more complex than any model might encompass. López-Acuña proceeded to catalog the various

and sometimes disparate entities that currently address global health risks, along with their leadership:

- The Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN), as specified by the IHR (WHO-led);

- The IHR and other relevant mandates of the WHA (WHO member states and secretariat);

- The UN’s humanitarian coordination architecture:

- Emergency Relief Coordinator (ERC) and Undersecretary General for Humanitarian Affairs (UN-led),

- The IASC (UN and non-UN membership),

- Humanitarian country teams (UN-led),

- OCHA (UN-led), and

- Criteria for defining an L3 humanitarian emergency5 (UN-led with IASC);

- The UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction;

- Special Envoy of the UN Secretary-General (position assigned for H5N1 avian influenza, Ebola, and food security);

- Ad hoc UN health emergency missions (e.g., UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response [UNMEER]);

- UN Security Council resolutions (passed for HIV/AIDS and Ebola by member states); and

- UN General Assembly resolutions (member states).

Systems Coherence

As he introduced these agencies, López-Acuña highlighted several relevant points. Noting that GOARN and the IHR are essentially led by WHO, he reminded the audience that WHO is not merely its secretariat or HQ but is comprised of member states which (among other things) negotiated and ratified the IHR as a binding mandate. The humanitarian coordination architecture led by the UN is a massive entity, López-Acuña observed, of which WHO is part, but the overall system is governed by the UN General Assembly, not the WHA. Thus, he asked, is it realistic to believe that the interagency mechanisms and governance structures linking the multiple elements of the United Nations’ humanitarian coordination architecture can, or should, be recreated in a new entity? The current system may not function perfectly, but he urged attention to the breadth and depth of existing mechanisms and agencies involved in global health risk governance.

Going further, López-Acuña stated bluntly that the current system lacks coherence, consisting of three parallel tracks. The WHO-led infectious

___________________

5 See http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/512deb632.pdf (accessed January 8, 2016).

diseases/IHR track is “good for alert, but weak for response,” he said. It is not clearly or formally linked with the humanitarian response track, which has been well developed over the past decade but lacks sustainability or provision for preparedness or recovery. He characterized the third track, comprising prevention, preparedness, and risk mitigation, as compartmentalized, neglected, and insufficiently mainstreamed into the development agenda. These shortcomings have precipitated the abuse of such weak, ad hoc solutions as UNMEER, he observed.

The WHO constitution defines several functions relevant to governance for global health risk, as noted by López-Acuña. Per Article 2, WHO

- Directs and coordinates authority of international health work;

- Establishes and maintains collaboration with the United Nations, specialized agencies, governmental health administrations, professional associations, and other groups as deemed necessary;

- Assists governments, upon request, in strengthening health services;

- Furnishes appropriate technical assistance and, in emergencies, necessary aid upon the request or acceptance of governments;

- Stimulates and advances work to erradicate epidemic, endemic, and other diseases; and

- Proposes conventions, agreements, and regulations (WHO, 1948).

Article 28 defines the responsibility of the WHO Executive Board (comprised of representatives of 34 member states) as follows: “to take emergency measures within the functions and financial resources of the Organization to deal with events requiring immediate action. In particular it may authorize the Director-General to take the necessary steps to combat epidemics, to participate in the organization of health relief to victims of a calamity and to undertake studies and research the urgency of which has been drawn to the attention of the Board by any Member or by the Director-General.” Article 56 states that “a Special Fund to be used at the discretion of the Executive Board shall be established to meet emergencies and unforseen contingencies.” This article implies the commitment of member states to contribute to such a fund, López-Acuña pointed out, a commitment which he supported over creating something new.

The WHA recently approved the following resolutions reaffirming WHO’s role in emergencies, López-Acuña noted. But while these mandates are clear, they have not been adequately resourced or effectively managed:

- Resolution WHA 64.10 on strengthening national health emergency and disaster management capacities and resilience of health systems and

- Resolution WHA 65.20 on WHO’s response and role as the health cluster lead in meeting the growing demands of health in humanitarian emergencies.

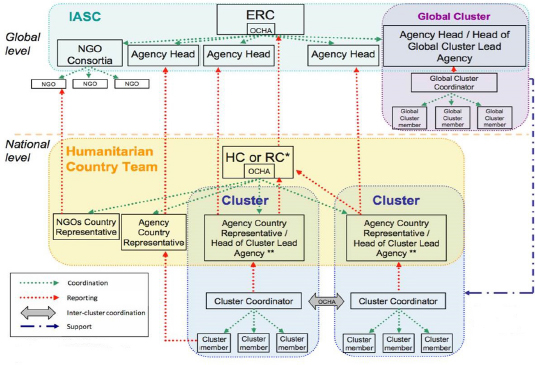

López-Acuña briefly introduced the UN’s complex humanitarian coordination architecture under the IASC (see Figure 7-3). Led by the ERC, the IASC is an interagency forum for coordination, policy development, and decision making. Its membership represents 10 UN agencies, and nearly as many external agencies as standing invitees. Another feature of the humanitarian coordination architecture—cluster coordination—was established in 2005.6 Clusters are groups of humanitarian organizations (UN and non-UN) working in sectors (e.g., shelter, food, and health) that are activated to meet clear humanitarian needs, when there are numerous actors within sectors and when national authorities need coordination support. In leading the Health Cluster, WHO works with more than 50 UN agencies and NGOs to organize and coordinate the health response to an activating crisis.

But despite the existence of this extensive health and humanitarian architecture, Ebola in West Africa became a humanitarian emergency and a global health risk, López-Acuña observed. In September 2014, after the late awakening of the alert and response system and of the humanitarian response, UNMEER was launched as a “remedial action” to reduce the reputational risk of the UN system and the international community at large, López-Acuña stated. The United Nations had never created an entity like this before, and it was created quickly, by resolution of the UN General Assembly and of the UN Security Council, he pointed out: a temporary measure to meet immediate needs. It ended on August 1, 2015, after which WHO again assumed oversight of the UN system Ebola response, he reported. UNMEER came very late in the game, and many people in the affected countries believe it created unnecessary layers of bureaucracy and additional coordination challenges, he observed. “I don’t think we should be looking at that as a paradigm of institutional response for the future,” he concluded.

López-Acuña reinforced earlier statements that global health risks extend well beyond the domain of health. He disagreed that WHO’s constitutional mandate is unclear; rather, he insisted that it is weakly implemented and cannot be enforced. He also disagreed that an independent entity could solve the problem of member state noncompliance with the IHR, due to the persistent, difficult issue of sovereignty. While he agreed that no entity is currently charged to deal with global health risks specifically, a reformed

___________________

6 See http://www.unocha.org/what-we-do/coordination-tools/cluster-coordination (accessed January 8, 2016).

NOTE: ERC = Emergency Relief Coordinator; HC = Humanitarian Coordinator (OCHA); NGO = nongovernmental organization; RC = Resident Coordinator (OCHA); OCHA = Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. * If a separate HC position is not established. ** The Agency Country Representative reports to his/her agency on agency responsibilities and to the RC or HC on cluster responsibilities.

SOURCE: López-Acuña presentation, September 2, 2015.

WHO could coordinate the many existing mechanisms that might contribute to such an effort. The synergy of existing global entities, mechanisms, or platforms is essential, he observed. To ensure that it works seamlessly, he urged greater efforts toward systems coherence.

In conclusion, López-Acuña believed that an additional UN independent entity of interagency composition to deal with global risks is not really needed. The global architecture is already crowded, he pointed out, and the creation of new entities contradicts the course the United Nations has taken to reform and streamline, guided by the recent Sustainable Development Goals. Most of the capacities and functions needed to address global health risk governance—and many of the mandates to do so—lie within the purview of WHO, López-Acuña argued.

CONSIDERATIONS ACROSS HYPOTHETICAL MODELS

Several participants shared their reactions to the hypothetical models and the strengths and weaknesses across the different options. Kenji Shibuya of the University of Tokyo spoke from his perspective as advisor on global health to the Japanese ministry of health, as the country prepared to host the 2016 G7 Summit. Reflecting on the workshop discussion, he agreed with various other speakers that scapegoating WHO for the shortcomings of the Ebola response in West Africa was not a solution. However, he cautioned participants to be realistic about the difficulties they may encounter to make real change, and enlisted a quote from a 1994 editorial in BMJ:

In the absence of strong leadership, there are long-hidden fault lines in WHO structure opening up, first the dislocation between management and staff, dissociation between headquarters and regional offices, and the contradiction between WHO high profile particular intervention programs and its stated goal of integrating primary care. (Godlee, 1994)

Clearly, WHO has not changed much in two decades, Shibuya observed, but the world has changed—and in particular, the world of health and humanitarian responders. He agreed with Piot of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and Goyet among others, who advocated for pragmatic and effective, but limited, reform of existing global health governance, rather than trying to overhaul the current system—or add to it new governance entities. We can achieve more effective global governance only through a series of impactful changes, he insisted.

Linking Universal Health Coverage to Health Security

Regarding the proposed models, Shibuya first observed, “we still tend to focus on 20th-century dogma of classic health security at the population level, namely border control.” As other speakers have stated, linking national security with global health threats can raise public awareness of the need for preparedness, but a border control/national security approach to outbreak prevention and control is insufficient, he observed. Namely, it ignores universal health coverage, which is the foundation of both individual and population health security. Linking the two—rather than creating a new, separate disease control entity—is an idea Japan hopes to emphasize at the next G7 Summit, he remarked.

We should not underestimate the extent to which the public distrusts authority, Shibuya observed. Recalling St. John’s statement that “if you lose the trust, you lose the battle,” Shibuya described WHO as “losing the trust of the general public and . . . exaggerating the dissociation between the public and their authority.” Thus, in the wake of the Ebola crisis, he urged WHO to avoid any more growth of the system in Geneva, and instead to use forums to bring UN agencies together with private-sector and civil society members to encourage open dialogue and transparency. He noted that several robust, pragmatic solutions had already been raised in the few days of discussion. Finally, Shibuya suggested that designers of the framework for global health risk governance could learn valuable lessons from other sectors, such as finance and cybersecurity. They can provide examples of frameworks, demonstrate how they handle crises, invite buy-in by developing countries, and open dialog with stakeholders, he advised.

Kimball of Chatham House recalled that “unprecedented and tragic failure” at all governmental levels—not just on the part of WHO—created the Ebola crisis. She observed that there is a drive to learn from these types of compelling situations and highlighted several key principles that were articulated throughout the workshop, including the importance of community involvement, expanding on systems that are already built and can be scaled up, and, importantly—to “do no harm.” While we have a resilient global health system, Kimball asserted, adjustments are needed in several key areas of awareness, diversity, self-regulation, integration, and adaptation (Kruk et al., 2015). In some areas, these principles do exist, but the information does not reach poor and developing countries, or the diversity is weak because traditional healers or the humanitarian community is not included in systems design. Regarding self-regulation, she described feedback loops that allow a two-way flow of information. Lacking such a system, the Minister of Finance of Liberia had absolutely no idea how much money was coming into his country, who it was coming from, and what it was for, she observed. This occurred because donors failed to moni-

tor and report what happened to the funds they supplied. Finally, related to adaptation, she noted the importance of mechanisms that permit self-correction rather than requiring disruptive structural modifications—which could include incentives for the IHR compliance.

With these attributes in mind, Kimball addressed the four models, endorsing the proposed center for health risk management within WHO, and in particular its mandate to coordinate the work of nonstate actors in emergency response. However, she added, the funding of such a center must be structured to ensure that the money is ring fenced, that the resources are being well used, and that that center is functioning as it was designed, she advised. She also advocated the use of simulation exercises to “pressure test”—and thereby improve—health emergency responses coordinated through the WHO center. For example, she said, it would be important to know if the center reaches out to the rest of the United Nations, if its alerts and terminology are understood, and if it efficiently mobilizes logistics. “This can all be done through simulation over the first year, and it needs to be very closely monitored,” she added.

Rasanathan of UNICEF, outlined several comments on the models that resulted in five main points:

- The tragedy of the Ebola epidemic shows that global health systems need to better support countries’ preparation for and response to disease outbreaks. What happens in countries is crucial to global health governance, he observed, but change is needed at every governmental level. Model 1 is necessary, but not sufficient, to support that goal, he concluded.

- Governance must take into account the specific challenge of responding to outbreaks in countries already in crisis or weakened by recent upheaval. These countries have fragile health systems.7 Ebola exacerbated the poor delivery of essential health interventions, adding to the toll from the disease. However, he advocated consideration of how efforts geared toward governance and disease outbreaks can strengthen health systems to respond to everyday needs of the community. This approach is equally applicable to preparedness and response; linking health security and the universal health care agenda, and thereby gaining the trust of communities, is essential for effective response to global health threats, he declared.

- The world needs a strong WHO; there is no credible alternative. History suggests that institutional proliferation does not necessarily strengthen national health systems or country capacity overall,

___________________

7 For example, he said, in Sierra Leone before Ebola in 2013, 40,000 children under age 5 died of all causes.

-

Rasanathan stated, and it can also impose costs associated with fragmentation and duplication. Moreover, countries clearly do not want to deal with even more health actors, all of which argues against Model 4.

- Models 2 and 3 have much within them to recommend, he stated, and endorsed strengthening WHO and improving coordination among various global actors, including UNICEF, as well as how they collaborate with both national governments and the existing humanitarian response architecture. “The key questions are how to better coordinate the different global and regional or national actors, including within institutions themselves, and in particular how to handle the challenge of multisectorality.”

- A strengthened WHO at the helm of global health risk governance must make better use of the UN system’s assets and resources, such as the existing humanitarian emergency response system and the cluster system, and bridge the deep cultural differences between those who work on disease outbreaks and those who traditionally work on humanitarian emergencies, Rasanathan stated. This strengthened WHO should also consider innovative mechanisms that can be mobilized in an outbreak, including long-term agreements with civil society organizations in the private sector, he said. All organizations, including WHO, need to overcome horizontal and vertical segmentation, so as to flexibly respond to crises without changing their formal structure. This requires better data sharing between sectors (and clusters during outbreaks) and timely technical guidance.

Given these considerations, Rasanathan cast his vote for Model 2, with the proviso that WHO proves capable of coordinating all the necessary functions of global health risk governance. If not, he offered that aspects of Model 3 might be required, although there should be caution in considering a greater role for OCHA. In either case, he added, “it is essential to use the imprimatur and status of the Secretary-General to bring together the UN system and other actors, given that only the Secretary-General has . . . the status to steer and control the agencies in working together.” The roles of the Security Council and General Assembly need further definition in the framework, he noted. Finally, Rasanathan observed that no matter the model, issues of genuine community involvement, the special needs of post-conflict and fragile states, and working with civil society and the private sector need considerably more thought.

Evaluation of IHR Compliance

While WHO has many reasons to refrain from public evaluation of member states’ compliance with the IHR, the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel felt that “a report that clearly showed how countries were fulfilling their legal commitments” was needed, according to Kickbusch. This report, she stressed, was not intended to be simply a ranking or a list, but a way to show countries, by example, how to meet the regulations’ provisions. In addition, she said, the report could highlight emerging security issues and promote a better overall understanding of health security. As to the question of who appoints the members of the independent oversight board (and, therefore, to whom they owe their allegiance), Kickbusch suggested that the WHO Director-General and the governing bodies of the United Nations could jointly appoint the board—much as they did the Ebola Interim Assessment Panel—and charge them with delivering an independent report. Any such body would be informing the United Nations, as well as reflecting on the WHO member states, she pointed out.

“Before we start reforming WHO, I think there are many other things we need to reform,” Tomori of the Nigerian Academy of Science observed. African countries have shifted responsibilities for national health capacities to WHO, which in turn has been weakened in that region by decades of misapplication and misappropriation of funding, he lamented. “As donors and recipients, we are being dishonest with each other about building capacity,” Tomori declared. “You are building your own capacity to do for me what I should be doing for myself.” In Africa, capacity has been built in an environment where it simply cannot function, he argued, and reforming WHO at the regional and international levels will not help this situation. The solution will require leaders of African countries to reform themselves and create an environment where this process is possible to maintain, he concluded.

Lacking Improvement at the Country Level

Elias of the Gates Foundation expanded on the notion, raised by both Kickbusch and López-Acuña, that the “models” actually represented complex systems. He cautioned against the unintended consequences of disturbing the existing system of global health governance—and especially the consequences of replacing it altogether. As others have noted, WHO’s structure is less a problem itself than the overall coordination of the complex system that it is a part of—the global health governance architecture, Elias stated. Gradual improvements in the structure of WHO and its interactions with nonstate actors and civil society at the global level have produced positive (if not dramatic) results over the past decade. However,

improvement at the regional and country levels over the same period has been “hypervariable,” resulting in “very strong country offices and some exceptionally strong regional offices, and . . . very weak country offices and weak regional offices.” When a health threat arises within a weak jurisdiction, as was the case with Ebola in West Africa, crises ensue, he observed.

Elias said he favored Model 2 as the likeliest means to achieve leadership, coordination, and alignment within the UN system. Model 1, he declared, provided an insufficient “shock to the system,” while Models 3 and 4 threatened to overwhelm it. However, he acknowledged, many details of Model 2 remain to be resolved: funding, the member states’ inclination to change WHO’s governance structures, and—given criticisms of UNMEER—linkage with the broader UN system. Looking beyond WHO reform and IHR compliance, Elias urged attention to opportunities for improving global health governance through more effective engagement with the private sector, civil society actors, and foundations. In particular, he advocated management of data and information on outbreaks as a “critical resource” and investment to promote citizen activism for capacity building.8

Critical improvements in global health require political and technical leadership at the national level, as well as within the global health community, Elias pointed out. “I don’t think we can lay the whole blame for this [Ebola crisis] on the WHO or the UN system,” he said, noting that engaging levers for effective change outside the UN system, and building strong systems at the ground level as Tomori stated, would be preferable to making changes within its complex network.

Accountability at the International Level

Kapila spoke in his role as UN Special Adviser for the inaugural World Humanitarian Summit in May 2016, the 25th anniversary of the UN resolution that established its current humanitarian architecture (as depicted in Figure 7-3). He noted that mistrust of global health governance is a recurring issue that emerges across all types of meetings. In country after country, he said the message was that the global community should be there to support efforts but should not be overstepping sovereign nations and decision making. The UN Secretary-General has appointed a High-Level Panel on Humanitarian Financing, which is due to report in December 2015, according to Kapila. Their charge is to find a predictable financing mechanism for global humanitarian needs, including health emergency

___________________

8Here, Elias noted UNICEF’s U-Report program, a free SMS-based system that allows young Ugandans to report on their communities and work with other community leaders for positive change. See http://ureport.ug/about_ureport (accessed January 8, 2016).

needs. The panel’s recommendations for achieving this goal resemble those of several post-Ebola commissions and panels with regard to independent assessments of capacities and accountabilities, he noted. They did not mandate reforms of the UN system, but instead focused on “changing processes, attitudes, approaches, improving tools, and most of all, providing inspiration to people who need hope.” Accordingly, he dismissed Model 4, saying that trying to change the IASC or UN system would be a waste of time. Processes and mindsets need to change, not structures, he argued; new tools and technologies must be brought online.

Heywood of Section27, South Africa, expressed agreement with Kapila’s views, and characterized WHO as a democratic structure that acts in undemocratic ways, insulating itself from aspects of democracy that bring about change. “There’s neither accountability nor consequence for the failings of the WHO,” he observed, and wondered how they might be introduced. “Accountability isn’t accountability of bureaucrats to each other,” Heywood declared. The people whose health depends on WHO must gain influence over the organization, he insisted. Unfortunately, he added, there is little financial support to encourage such citizen activism “because lots of people, including donors like the Gates Foundation, are nervous of some of the things that citizens do and say.” “If we don’t address those issues around citizen activism, developing and protecting peoples’ voices, then it will be very, very difficult to do anything other than leave the WHO as something that sits in some sort of space in Geneva about which ordinary people have no understanding and no interest,” he concluded.

This page intentionally left blank.