The value of building local, regional and national health system capacities was a topic raised by multiple participants throughout the workshop and is discussed further in this chapter. Components of a strong, resilient, and sustainable health system, suggested several participants, should encompass functional day-to-day primary health care delivery, the infrastructure to implement essential public health functions, sufficient health care workforce capacities, and a reliable supply chain.1 In addition to delivering best-quality care to populations, many participants suggested that a strong everyday health system should be resilient and flexible enough to respond quickly to disease outbreaks or other public health emergencies—and be able to receive assistance effectively from regional or international support systems as needed—without compromising or terminating its ability to continue delivering primary care.

López-Acuña remarked that these capacities should meet the core commitments of the International Health Regulations (IHR), which are fundamental to resilient health systems. Fowler emphasized the need to build these capacities during the interoutbreak period in order to establish a coordinated health systems response, guide clinical care, and carry out real-time practice-informing investigations to fully prepare for when an emerging disease, outbreak, or pandemic does occur.

STRENGTHENING DAY-TO-DAY HEALTH CARE DELIVERY

“When an aware, diverse, self-regulated, integrated, and adaptive community-based primary health system preexists—health care can remain resilient, mitigating effects of epidemics.”

—Raj Panjabi, CEO of Liberian nongovernmental organization Last Mile Health

__________________

1 However, these are all components of a resilient system, and not representative of many fragile health systems in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) that struggle with routine needs and were the ones needing to respond to the Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak.

Several participants characterized a country’s fundamental capacity to deliver everyday, primary health care as a key determinant of its ability to ability to respond to emergencies. Citing the 2006 World Health Report stating that many national health systems are weak, unresponsive, inequitable, and even unsafe (WHO, 2006), Jim Campbell, Director, Health Workforce, World Health Organization (WHO) Executive Director, Global Health Workforce Alliance, expressed concern over whether countries who struggle to provide even the most basic health services to their populations can realistically be expected to take part in the unbroken line of defense, constituted by strong national public health systems, on which global public health security depends. He argued that strengthening weak health systems in these countries is essential not only for delivering the best possible public health to their populations on the local level, but also for safeguarding public health on the global level. Similar to Rasanathan’s comment in Chapter 2 regarding sanitation practices, Campbell highlighted the importance of first building a country’s basic health capacities as the primary objective, followed by basic public health capacity and then its capacities for outbreak management and emergency response. A community can respond to extraordinary events when it is able to meet its day-to-day public health and health care challenges.

López-Acuña described the objective of universal health coverage as a prerequisite for a reliable and resilient health system. He noted that people with greater needs tend to use health services less than other population groups, and that when they do use those services, they incur high and sometimes catastrophic costs in paying for their care. Only one in five people in the world has broad-base social security protection, including lost income, and more than 50 percent of the global population lacks any form of social protection. Noting that 2 billion people across the world do not have access to equitable health care services, Campbell provided an overview of the concept of universal health coverage as defined by WHO (WHO and the World Bank, 2013). Its goal is that everyone in the population obtains the good-quality essential health services they need without enduring financial hardship. As expected, this is much more difficult to realize in practice than in theory, and many countries still struggle to cover all residents without burdening patients with enormous costs (Saksena et al., 2014). Regarding the distribution of health care coverage, Panjabi noted that it must extend even to the most remote and hard-to-reach areas—so-called blind spots—where people have no access to care. He emphasized that it is often in those extremely remote areas that pandemics originating in zoonoses start, and where they can be the most difficult to eradicate. Achieving coverage in remote areas, he suggested, can be facilitated by a community-based primary health care system.

Raphael Frankfurter, Wellbody Alliance, commented that a resilient

health system should draw patients to it, which necessitates interventions including logistical and functional support but also community engagement and attention to social dynamics, especially in communities with low health care utilization. Referring to the EVD outbreak in Sierra Leone, he noted that the health system was unable to adapt quickly enough in a humane and empathetic way to the complicated social dynamics at play in affected communities to draw patients into the EVD treatment and control system. He described this schism between community values and the sometimes “draconian” approach of the health care system as having profoundly systemic effects, given that there are continued cases of EVD persisting in Sierra Leone. Lamptey similarly warned against responding to disease on an ad hoc basis. A community’s health needs are not only related to infectious disease; thus fully engaging with a community means engaging across the board and across time.

Several participants noted that strengthening day-to-day health delivery systems is a prime opportunity for “homegrown” solutions, and should serve as a platform to nurture and encourage local solutions to strengthen primary health care. They suggested that leadership should take an active and accountable role in establishing clear priorities to take responsibility for achieving primary health care health goals, considering alternative funding sources, and including a range of partners, such as the private sector, universities, and locally based domestic or international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). They suggested that the creation of a network of resource centers could help to disseminate information, to support leaders, to mobilize funding, and to identify potential solution providers. Ideally, these strategies would lead to lower, more sustainable costs.

BUILDING PUBLIC HEALTH CAPACITIES IN EVERYDAY HEALTH SYSTEMS

Multiple participants highlighted the need to strengthen basic public health capacities and functions during interoutbreak periods and to integrate those capacities within health care delivery. López-Acuña advised that a health system’s basic capacity for better public health practice is its ability to discharge the essential public health functions, which is contingent upon a strong public health infrastructure. Such an infrastructure comprises the fundamental elements of

- Information

- Skilled human resources and satisfactory working conditions

- Organization, including legal frameworks, managerial processes, accountability, and evaluation

- Indispensable physical resources

- Essential support and auxiliary services, such as public health laboratories, logistic systems, and physical infrastructure

Characterizing the public health workforce as too often neglected and undervalued, he called for prioritizing the development of a workforce that is trained and prepared for carrying out public health tasks. Ian Norton, Foreign Medical Teams Working Group, WHO, Australia, remarked that building a global health workforce is contingent on first developing the national public health capacities that feed into it. As outlined in Chapter 2, multiple participants called for the health care and public health system to be integrated and interoperable. A key component of this strategy is the education of clinicians and health workers in public health concepts. As a part of developing national public health capacities, using similar models in a region could also help countries harmonize some of the indicators to better understand what they are measuring and when something should be a “red flag” or more of a routine detection. For many countries just beginning this process, information sharing across borders could help to alleviate variations in detection and response when the threats are geographically similar.

Understanding Public Health Capacities and Capabilities Within a Country

In order to build public health capacities in a country, accurately assessing the system’s current capacities to pinpoint priority areas of need is a potential first step. Several participants highlighted the importance of accurately assessing and monitoring the public health capacities and capabilities within each country, in order to focus initially on strengthening areas of weakness in preparation for emergency response. Fowler noted, for instance, that the health system’s ability to respond to the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto was compromised by lack of knowledge about the system’s actual capacity. Campbell described how in countries most affected by recent outbreaks, basic information about their respective national health workforces was very often lacking: records were not available in terms of the clinical capacity of the health workforce or its managerial support, its public health capacity, the location of health care workers, where they were deployed, and so on.

To accurately gauge national health workforce capacity, Campbell reported that participants suggested using a census of national capacity to evaluate the workforce in its broader sense, followed by assessing the specialized areas of laboratories, surveillance, and public health management. Campbell noted that this actually reflects already agreed-upon IHR stipulations for member states, who have a duty to support those countries

with inadequate capacities. He called for international duty bearers, in addition to international donors or partners, to assume the responsibility for supporting this national process.

BUILDING HEALTH WORKFORCE CAPACITIES

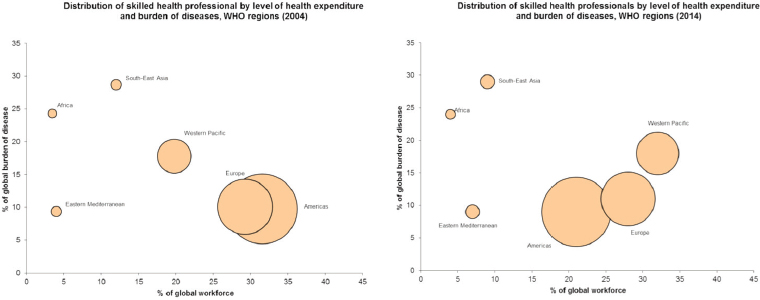

Campbell referenced David Heymann’s recent recommendation to the World Health Assembly (Heymann, 2015), which stated that the foundation of a global health emergency workforce is the national health workforce in every country. He offered a global perspective on national health capacity status, referring to data comparing the distribution of skilled health professionals by level of health expenditure and burden of disease in 2006 with recent data. He noted that while some regions and countries are making progress, Africa has stood still: it represents 24 percent of the global burden of disease but has just 3 percent of the global health workforce (see Figure 3-1).

He suggested that not only is the number of health professionals in Africa failing to keep pace with the population, the number may actually be falling due to forces such as labor mobility and labor migration pulling them away from their home countries and contributing to “brain drain.” During the EVD outbreak, there were additional brain drain concerns as many frontline health care workers feared for their own safety at work, lacking any guarantee of health insurance or disability pay for themselves if they were to get sick. Noting that the data captures the number of skilled health professionals specifically, he called for better understanding of the respective roles and contributions of advanced clinical practitioners, mid-level health workers, and community-based practitioners in devising better ways to build health workforce capacities.

Bolstering the “White Economy”

Campbell remarked that multiple World Health Reports over the past 10 years have highlighted the role of health care workers as a fundamental component of health care systems. To strengthen this capacity in national health systems, he suggested investing in the so-called white economy,2 a job-rich sector comprising:

__________________

2 The “white economy” is the economy related to the uniforms of health professionals. “White jobs” include those in all sectors of health care—public health, pharmaceuticals, nursing, health care delivery, etc.—with the exception of volunteer workers. Campbell argues that this industry has untapped potential for economic growth, especially in Africa where health care workers often operate on a volunteer basis.

SOURCE: Campbell presentation, August 6, 2015.

- Health workers in the public, private, faith-based, and defense sectors

- Anyone involved in delivering health care services (e.g., doctors, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, dentists, and allied health professionals)

- Public health professionals

- Health management, administrative, and support staff

- Health care industries and support services, including residential and daily social care activities for the elderly, disabled, and children; pharmaceutical industry; medical device industries; health insurance; health research; e-health; occupational health; and spa workers

- Salaried and self-employed workers (but not volunteers)

Campbell explained that the white economy offers a triple return on investment, driving economic growth, social development, and global health security. Strengthening the health and social sectors, as well as the scientific and technological industries, acts as an engine of economic growth and thus boosts skills, innovation, jobs, and formal employment, especially among women and youth. It serves as the foundation for the equitable distribution of essential promotive, preventive, curative, and palliative services that are required to maintain and improve population health and remove people from poverty.

Where countries are unable to achieve prevention and control by themselves, they need rapid international and regional support for disease surveillance and response (WHO, 2007). Campbell suggested that investing in the white economy is a key foundational step in meeting the core capacity requirements of IHR and ensuring global health security. IHR Core Capacity 7 is its human resource capacity; Campbell called for its integration within the health labor market to move toward the objective of universal health coverage, and advised against global health security becoming the next vertical agenda. Campbell suggested that incorporating universal health coverage efforts with the Open Working Group Proposal for Sustainable Development Goals (UN Sustainable Development, 2014) could provide a new paradigm for health care human resource development. By linking public health to the other elements in health resources funding, it could demonstrate how investment in health resources can have a much broader impact, for example, on gender equality, trauma, poverty, employment, education, child health, and nutrition. Campbell outlined the objectives of WHO’s Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030 (WHO, 2014) as a potentially useful model (see Box 3-1).

Engaging Community Health Workers in the Primary Health Care System

To address the previously mentioned gap in remote health care delivery, Panjabi called for creating a new workforce to save lives of people living in extremely remote areas by professionalizing community and frontline health workers to extend the reach of the primary care system. He charted a multifaceted strategy for doing so:

- Recruitment combines community input with high standards, including screening, practical assessment, and a probation period.

- Preference is extended to unemployed women and youth.

- Training involves rigorous and continuous theory coupled with practical training, with a component on surveillance, diagnosis, and treatment of the top mortality-causing diseases.

- Trainees continue to receive regular evaluation and on-the-job mentoring.

- Diagnostic, curative, and nonmedical equipment is reliably stocked at points of care to enable high coverage and facilitate supervision.

- Workers receive clinical and nonclinical supervision, weekly peer supervision, and district- and county-level management.

Emphasizing that professionalizing entails not just training, but also funding, Panjabi explained that the program creates career opportunities for workers and recognizes their life-saving work. Payment enables more accountability for performance and greater likelihood of retention. Panjabi described a 2011 project launched by his organization, Last Mile

Health, together with Liberia’s Ministry of Health. The project provides community-based primary health care to residents of Konobo District through professionalized community health workers and nurse mentors (Kenny et al., 2015). At baseline, 22 percent of mothers had full maternal care cascade (antenatal care visit, facility delivery, and postnatal care visit) and 23 percent of children under 5 years of age had never sought health care for fever-related illnesses at a health facility. Prior to the EVD outbreak in 2014, the community health care workers had increased antenatal coverage to 97 percent and facility deliveries to 82 percent; 100 percent of children were covered by services for malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhea treatment. Panjabi reported that the program was resilient despite the EVD outbreak.

Sustainability

Panjabi stated that community health workers have an economic return of up to $10:13 that is due to increased productivity from a healthier population, the potential for reducing the risk of epidemics such as EVD, and the economic impact of increased employment among community members (Dahn et al., 2015). During outbreaks, the workers can play an active and vital role, as well as sustaining life-saving primary health services both during and between those outbreaks, such as treatment of pneumonia, HIV, malaria, tuberculosis, and maternal, adult, newborn, and child conditions (Perry and Zulliger, 2012). He reported that such services are estimated to prevent up to 3 million maternal, perinatal, neonatal, and child deaths annually.

Lloyd Matowe, Director, Pharmaceutical Systems Africa, queried how the community health workers obtain needed medications on a sustainable basis, and Panjabi replied that while facility-based delivery was maintained for community case management, vaccine coverage dropped regardless of what system was in place. The system is currently centralized with the Expanded Program on Immunization group in Monrovia, and has not been decentralized at the county level. He remarked upon the need to bring in supply chain specialists for the national program to help address ongoing national- and local-level issues. He noted that when health care is initiated in areas not previously served, demand changes immediately (because predictions were based on previous demand), although in remote areas many diagnoses and subsequent demand are still missed.

David Sarley, Senior Program Officer, The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, characterized community health workers as being “at the forefront

__________________

3 During subsequent discussion, he clarified that the cost of the program at that scale is $8 per capita, including overhead, management, support, and recruitment training.

of identifying problems and also serving their communities.” In that context, some participants also suggested strengthening alternative channels, such as civil society and local NGOs, in an integrated and sustainable way. Another idea to arise was that the government could have specific roles in setting the training curriculum and supply train protocols, contracting out service needs to local district and county health teams to strengthen capacity. Furthermore, community health workers could be linked into national sources of supply by utilizing multiple communication channels to ensure comprehensive data sharing.

Building a Strong Workforce: Education, Training, and Retention

Participants, including Perl and Fowler, recognized the need to better educate clinicians and health care workers regarding the essential concepts of public health and emerging infectious diseases, which are not generally covered in medical school or other training programs. Anyangwe highlighted the requirement to educate and train relevant workers on IHR compliance according to need. She further suggested that training health workers on all levels about the basics of disaster risk management is imperative; she noted that despite epidemic and emergency response, a health system must continue to maintain its regular functions or system growth will not occur.

Patrick M. Nguku, African Field Epidemiology Network, Nigeria Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program, and Abdulsalami Nasidi, Director General, Nigerian Centre for Disease Control, offered a set of recommendations with respect to workforce development for a sustainable and resilient health system. Training should augment existing systems through education in the basics of prevention, detection, and response. It should span multiple diseases and be contextual and adaptable to current and future needs. It should align with government structures at the district and state levels to help ensure that all states are covered according to their population and public health needs. Conducting surveillance and response activities through regular drills and exercises is critical, as is the ability and authority to mobilize quickly during emergencies. Countries should be empowered to devise local solutions to local problems, with the government leading and coordinating while incorporating appropriate support from partnerships. Ultimately, they advised, vertical disease funding should parlay into horizontal system strengthening.

Needs-Based and Competency-Based Training Strategies

Fowler remarked that another important task, sometimes overlooked, is general education and training in the basics about how to care for

people—at all levels of practice—which can be done through good development of nursing with a physician team. These basic skills include recognizing people who are sick early on, learning how to place an IV, hydrating people, and providing existing treatment therapies. Perl described educating health care professionals as a key component of developing infrastructure and sustainable response, and pointed to some operational challenges of doing so. She noted that while distance learning has its benefits, it limits the mentoring experience that is critical for growth; professionals should thus be mentored in a way that imparts experience and the exposure that they apply to their theoretical knowledge. Matowe commented on the tendency to train people based on perceived need rather than actual need, or training people in the wrong areas. He recommended that any training component needs to be specifically tailored to those affected, on competencies specific to the particular setting.

A participant mentioned that the need to improve training is intensified by fact that the most undertrained health care workers tend to work in the facilities that have the most needs. Further, she suggested that training programs should include traditional health practitioners and those from the private sector. Devising training and education programs requires partnerships with government at the local, national, and regional levels and data collection about the current state of the health workforce and its future needs (as well as providing metrics for the success of the program). Anyangwe noted that training requires both adequate infrastructure as well as targeted funding; in many cases, countries plan to increase training but do not commensurately increase the infrastructure to cater for the increased numbers that they want to train. Replying to a suggestion about training the heads of health teams in local communities, she remarked that a training strategy should also depend on the cadre being trained. For example, for a team consisting of medical doctors, nurses, and midwives, uniform training for the whole group may not be appropriate: again, she said, training should be based on identified need. Frankfurter made a direct call for investment in African formal training programs in academic centers across African universities, to encourage concrete means of collaboration to explore how international universities can play a role in building resilient health systems.

Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program’s (FELTP’s) Role in Nigerian EVD Outbreak Response

Nguku and Nasidi explained FELTP’s important role in implementing the response to the EVD outbreak in Nigeria.4 It was able to make available

__________________

4 Imported case in July 2014; 20 cases with 8 deaths; rapid response; 899 contacts / > 97 percent contact tracing daily rate; controlled within 8 weeks.

personnel for training workers (e.g., residents who had graduated from the program were ready to be deployed to train others5) and a highly skilled workforce for:

- Rapid response (due to FELTP trainees’ outbreak investigation competencies, interpersonal communication skills, and epidemiology background)

- Case identification and investigation

- Contact identification and monitoring using real-time, geographic information system (GIS)-enabled smart phone technology system, Open Data Kit6

- Surveillance

- Operational research to identify specific response gaps and make evidence-based decisions

- Deployment to other countries

Nguku and Nasidi remarked that the positive impact of FELTP extends beyond Nigeria and to other countries as well (see Box 3-2 for an overview of the program). Data are shared countrywide in publications documenting successes and lessons learned, as well as informing predictive models to prepare for future events (e.g., FELTP’s role during the 2007 East African Rift Valley fever outbreak in identification, risk analysis, cross-border collaborations, and modeling). Aceng described how Uganda has been training health care workers on the management of viral hemorrhagic fever and other epidemics for years, directed by continually updated training guidance. An inventory of all trained health workers is maintained so that the workers can be quickly contacted and deployed as needed. At new outbreak locations, workers who have been trained deliver training to other workers to increase capacity.

“We need to look at the differentiation between salaried, nonsalaried, and community-based practitioners. One is a worker; one is a volunteer; one is a contradiction in terms. If you try to run a health care system on a volunteer basis that’s not a resilient health system.”

—Jim Campbell, Director, Health Workforce WHO

__________________

5 One hundred graduates were involved; within 1 day of suspicion at least 15 were deployed.

6 All contacts identified and followed up; more than 18,000 contact visits and interviews in 3 states with > 97 percent coverage rates.

Workforce Protection, Compensation, and Retention

Patrick Kelley, Director, Board on Global Health, Institute of Medicine, U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, remarked that needs-based training is not a solution for everything; what happens after training should be taken into consideration, that is, how to enable the workforce to maintain performance and how to improve workforce retention rates. Campbell similarly commented on the challenge of recruiting and retaining workers in the health care sector. He noted that not enough health care workers are being produced to meet the need, there is not an adequate labor pool, and health care workers who are trained are very often lost due to lack of compensation or other factors. He reported that 41 percent of the health workforce are not in the public sector, and attributed this to weak performance, management, and accountability. He called for a more integrated approach to understanding what the health workforce needs.

Ensuring workforce safety, fair compensation, and better retention rates were areas highlighted for improvement by multiple participants.

Improving Conditions of Service and Retaining Health Workers

Multiple participants suggested that health workers should be provided with incentives, such as fair compensation and improved conditions of service. In many cases, they noted, health care professionals do not have these proper conditions of service, including the provision that if they get sick while on duty, they are paid and care would be provided for them. As mentioned previously, personal protective equipment (PPE) in LMICs is often scarce, and workers also do not have sufficient protections from lethal diseases, making the probability of falling ill while working much higher and making the absence of disability or life insurance that much clearer. Fundamental to improved conditions of service are sustained, regular, baseline salaries and benefits, including life insurance. Doing so may mean shifting costs in a prioritized way or seeking funds from outside the system. Campbell remarked that models and strategies for community engagement are often prepared but not funded or sustained until an emergency, such that volunteers are expected to facilitate meaningful engagement on the basis of 1 week’s worth of training. He recommended formal employment, including salary, supervision, and a career pathway. Awunyo-Akaba of Ghana referred to the many volunteer health workers who have died and suffered without salaries, highlighting the moral imperative to examine benefits to families as well when workers become sick due to employment. Panjabi recommended providing volunteers with the opportunity to become professionalized community health workers held to the same standards as employed personnel and further commented that, “even if they are not literate they can still play a valuable role in care provision.” He also suggested paid referrals as economic incentives.

Aceng of the Uganda Ministry of Health commented that many countries have a trained workforce but face retention problems, particularly with the most qualified workers. Campbell cited the scale of labor mobility as a huge concern for health systems resilience, one which will need to be addressed by training as well as properly supporting workers through provision of adequate PPE as well as compensation and insurance policies. He added that economic costs arose during the Ebola outbreak because many health care workers refused to work under subpar conditions during the outbreak. These conditions, including lack of PPE and unpaid salaries left them extremely vulnerable and often led to the neglect of many health conditions, both chronic and acute. Dovlo of WHO’s Regional Office for Africa (WHO-AFRO) also agreed that a critical problem is the protection of health care workers, both in terms of economic stability (through consistent, fair

compensation) and workplace safety. He argued that health care workers are critical resources to the country and must be protected.

To address this problem of “brain drain,” Sarley suggested creating opportunity for talented individuals to return. Campbell described a framework (Sousa et al., 2013) for how the education sector and the dynamics of the labor market can combine to drive the push for universal health coverage. It would be guided by IHR policies that may serve to address migration and emigration, attract unemployed health workers, bring health workers back into the health care sector, and retain health workers in underserved areas.

Ensuring Workforce Safety and Mental Health

In the context of safety, a few participants highlighted a key impediment for bringing teams into the EVD response efforts: lack of access to health care if they became ill themselves. Thus, they highlighted providing access to safe environments (such as having available personal protective equipment or proper hospital isolation and ventilation measures), and appropriate safety training to ensure that workers were empowered to go back to work and to care for other frontline health care workers. A related concern is ensuring that countries continue this support and care for workers after international partners have left. Anyangwe of the University of Pretoria highlighted the importance of a long-term plan for continuous education of the entire health workforce—including traditional healers—about personal safety, infection control, hygiene practice, and transmission prevention for common critical diseases such as cholera and tuberculosis, and using that to bridge additional education on global health security and emerging disease safety.

As Petersen described, it is common for health workers to develop mental health conditions for a variety of reasons arising from their work. These conditions could potentially impact their ability to treat patients. A set of participants offered regular, deliberate assessments of health workers with risk categorization and implementing systems of care and support for them as a way to address this issue.

Strengthening Systems for Coordinating a Health Care Workforce

Several participants discussed ways to identify, mobilize, and coordinate workers across levels. They suggested the possibilities of a functional database of allied health professional bodies and of registries of traditional health practitioners. This would require adequate information technology (IT) infrastructure for the maintenance of databases, but it would help to promote cohesion and organization among health care providers. A par-

ticipant described one such politically supported plan in Ghana to identify, locate, and coordinate providers, as well as to identify anyone working outside of the group.

Norton described a further potential benefit of global registries for health teams, citing WHO-verified foreign medical teams as an example. For member states and affected populations, such registries ensure that teams have appropriate training and equipment, and that they are able to coordinate and attain established standards. From the perspective of the teams, he said, they are more likely to be well received by member states if they are on the registry. He noted that donors are also more likely to encourage teams to be registered for the purposes of quality assurance and accountability. Campbell remarked that Brazil has a strengthened capacity for outbreak response, because it does have a registry like this that identifies and locates each health care worker. Aceng described the multilevel coordination structures in place within Uganda’s health system (see Box 3-3). Because they are strong and well established, she said, they are able to respond quickly in both day-to-day and emergency situations.

STRENGTHENING SUPPLY CHAINS

Matowe of PharmaSyst Africa explained that in the Southern African Development Community member states, there are relatively few in-country pharmacists relative to the population, with many pharmacist responsibilities falling to other types of health care workers such as nurses. As a consequence, the supply chain for medicines was overwhelmed by the EVD crisis, with pharmacists ill-equipped to manage the disease and supply chain managers unable to determine what was needed.

“Despite years of investment in supply chain systems, particularly by the well-meaning and well-funded programs, systems remain weak in many resource-limited countries. . . . This then begs the question: is there need to change our approaches to capacity development?”

—Lloyd Matowe, Director, Pharmaceutical Systems Africa

He outlined four key components of the access framework for safe, efficacious, quality, cost-effective drugs (MSH, 2008): geographic accessibility, acceptability, affordability, and availability. However, he explained, many developing countries lack some or all of these features, due to factors such as poor dispensing practices and product management or essential medicines simply not being available at all. Substandard medicines are a pervasive problem in developing countries; he recounted the breakdown of data

on 325 cases of substandard drugs (including antibiotics, antimalarials, and antituberculosis drugs) reported to WHO. Of those, 16 percent had the incorrect ingredient, 17 percent had an incorrect amount of the ingredient, and 60 percent contained no active ingredient at all. Matowe provided a

SOURCE: Matowe presentation, August 6, 2015.

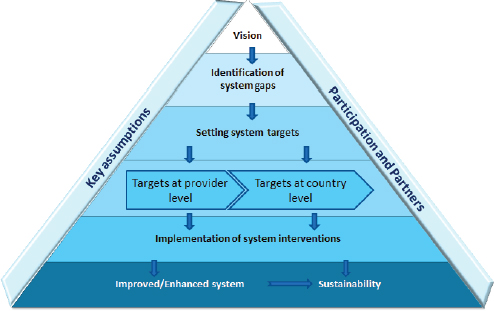

model framework for strengthening the supply chain management system (see Figure 3-2).

Calling for a paradigm shift to drive supply chain system strengthening, Matowe explained that traditional technical assistance is supply- and donor-driven, focused on short-term needs and filling gaps in capacity, and hampered by a lack of in-country stakeholder participation and insufficient monitoring and evaluation. A more contemporary approach, he suggested, would be country-owned and demand-driven, with a focus on building the country’s capacity and achieving long-term, sustainable changes. A mutual dialogue regarding performance between the country and technical assistance provider would underlie a results-based monitoring and evaluation; the program would be systematically designed and implemented to address broader institutional, political contexts.

Focusing on the element of country ownership, Matowe recommended that issues in the health supply chain system should be managed at the local or country level to ensure

- Engaged stakeholders and supply chain leaders are present in both policy and technical areas related to national health supply chains,

- Policies and plans are in place to support planning and sustainable approaches to system developments,

- Needs-based approaches are considered,

- Performance management approaches are in place and appropriately funded, and

- Professionalism of supply chain cadres is increased to demonstrate the importance of cadres working in supply chain management.

Responding to a comment from Sarley at the Gates Foundation about the identifying and supplementing the number of trained supply chain professionals in each country, Matowe commented that supply chain professionals are generally not recognized as such, and that such people in most countries are nonpharmacists only found in central medical stores in procurement. He suggested turning to people trained in supply chain management of vaccines and other commodities as a resource with the view to creating a new cadre of dedicated supply chain specialists. Another workshop participant noted the difficulty health care workers have in managing PPE supply chains and suggested that health administrators put a stronger focus on PPE supply chain management. Aceng commented that PPE supply chains in Uganda are strong because of support from the national government and external partners. Sarley highlighted the challenge of many countries having legislation that requires a physician or pharmacist being present during the outlining of this process.

To Awunyo-Akaba’s question about medical stores, Matowe responded that in-country medical stores are very diverse, pointing to state stores in Nigeria and Tanzania as working well. He noted less success in smaller countries, with centralized systems working from the National Drug Service down to difficult-to-reach areas. He highlighted the key question of which type of system is more efficient—one that is decentralized or one that is distributed from a central level—because the results of both are diverse. A centralized system enables better tracking of commodities such that gaps can be more quickly identified and addressed. In a decentralized system, regions are better equipped for their own specific needs, thus improving efficiency.

Noting that “stock outs,” or consistently having supplies out of stock, can cause a community to doubt the health system, Fallah asked about innovative examples to move drugs rapidly. Sarley cited the Gates Foundation’s development of unmanned aerial systems for this purpose (early experiments suggest that delivery may be provided within a 75-kilometer radius within 30 minutes of a drug request). However, he cautioned that the technological and operational components remain a challenge. Dave Ausdemore, Liberia Country Director, eHealth Africa suggested seeking initial funding from public–private partnerships to jumpstart this type of innovation. Jones of FACEAfrica added that countries like Liberia inevitably have longer wait times for validation and implementation of this type

of new innovation, and urged seeking concrete local solutions to address these concerns in the short term.

Government Collaboration with the Private and NGO Sectors

“When you rely on a single central medical store as your sole source of supply in a country, and you have an emergency, you have literally put all of your eggs in one basket. If you want to build a resilient supply chain—like any commercial supply chain that companies work with—you don’t put all of your eggs in one basket; you have several channels.”

—David Sarley, Senior Program Officer,

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Multiple participants suggested that governments could commit funding to contract out to private and NGO sectors. The aim of doing so would be to ensure quality product availability through the agile and resilient capacity to utilize different supply channels, geared toward increasing the availability of drugs, reducing expiries and the duration of stock outs, and establishing standards for identifying and eliminating all substandard drugs. Collaborating to this end would involve the public sector to manage and procure contracts, pharmacy chains, quality medicine vendors, and local, quality providers from NGOs, civil societies, local agencies, and the private sector. As Sarley presented, resources for implementation could include

- Operational funding for transportation, supervision, and warehousing

- Trained supply chain professionals, pharmacy assistants, and technicians

- Quality business supply chain education and processes

- Solar energy and long-holdover off-grid cold chain equipment for vaccines

Sarley noted that while having a central medical store is an important part of the supply channel for public safety and security purposes, a country should not have all of its commodities in a single channel. If there are available options run by a private-sector or NGO operation that would enable faster delivery of products to a particular district because of their existing transportation or management facilities, governments should contract out the work, according to Sarley. However, he cautioned that multiple channels should not be parallel channels: the objective should be to invest in a single supply chain with several component channels.

RESEARCH AND CLINICAL GUIDANCE

“Unless we start before these outbreaks are upon us with observational studies and clinical trial protocols we will never be ready to learn anything from these outbreaks that is durable, and we really must start in the interoutbreak period to figure out what we want to study when these things are upon us, otherwise we will not advance.”

—Rob Fowler, University of Toronto, Canada

Remarking that “outbreaks and pandemics are unpredictable but predictably recurrent,” Fowler and others highlighted the need for improvements in research and clinical guidance. During outbreaks, the lack of preexisting protocols can delay both studies and needed clinical trials, according to Fowler (e.g., the median time to initiate research on severe acute respiratory infections between 2013 and 2014 was 335 days). He urged that protocols designed to address unanticipated outbreaks and pandemics must be initiated during interoutbreak and inter-pandemic periods, cautioning that a reactive approach will not allow sufficient time to begin research before most outbreaks are advanced or completed. A further concern cited by Fowler and others was the use of non-evidence-based treatments in epidemic response due to a lack of available clinical guidance about how to treat patients. As Rubinson observed, when data are limited, opinion reigns. Thus, improving clinical guidance was suggested as a priority during interoutbreak periods, supported by collaboration with international partners and continually updated as new research- and field-based information becomes available.

From the perspective of a clinician on the ground during an outbreak, Rubinson of the University of Maryland remarked that while some disease features are predictable, such as sepsis/septic shock, the particular organs involved and its impact on disease course can be more difficult to determine. He noted that supportive care generally plays a major role until disease-specific therapeutics are available, and co-infection with endemic diseases or clinical features may overlap with those seen in endemic disease. He described how prior to 2014, clinical guidance about EVD care was based on limited data and care in very challenging environments. For example, decisions about oral versus parenteral fluid resuscitation and additional supportive care regimens were opinion based. Nevertheless, even postoutbreak with tens of thousands of patients treated, he stated that there continue to be more questions than answers regarding care. Currently, most guidance about EVD management largely relates to how to manage

general sepsis syndromes. He called for translating resource-rich strategies to resource-limited environments for high impact.

Fowler described the efforts of the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium,7 a global federation launched in 2011 of more than 40 existing clinical research networks. Its aim is to change the approach to global collaborative patient-oriented research about rapidly emerging health threats between and during epidemics, in order to generate new knowledge and maximize the availability of clinical information. Fowler was optimistic that this would provide a common and standardized basis for new observational research and clinical trials.

__________________

7 See https://isaric.tghn.org (accessed October 2, 2015).

This page intentionally left blank.