Medicare is the government’s health care program for the elderly (individuals age 65 years and older), those with permanent kidney failure (end-stage renal disease [ESRD]), and some individuals with long-term disability. Recent health care payment reforms aim to improve the alignment of Medicare payment strategies with goals to improve the quality of care provided, patient experiences with health care, and health outcomes, while also controlling costs. These efforts move Medicare away from the volume-based payment of traditional fee-for-service models and toward value-based purchasing, in which cost control is an explicit goal in addition to clinical and quality goals (Rosenthal, 2008). Specific strategies include pay-for-performance and other quality incentive programs and risk-based alternative payment models, such as bundled payments and accountable care organizations. In this report, these types of strategies will be referred to broadly as “value-based payment” (VBP). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (Affordable Care Act) prompted widespread adoption of VBP at the federal level by directing the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to implement payment reforms in the Medicare program and by establishing a number of tools CMS can use to achieve VBP goals. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) was commissioned to provide input into whether socioeconomic status (SES) and other social risk factors could be accounted for in Medicare payment and quality programs. The IOM convened an ad hoc committee to conduct a series of five reports related to this task, of which this is the first report.

CURRENT STATUS OF VALUE-BASED PAYMENT IN MEDICARE

The Affordable Care Act and subsequent legislation, including the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation Act of 2014 (IMPACT Act) and Medicare and CHIP [Children’s Health Insurance Program] Reauthorization Act of 2015, require CMS to implement VBP programs for Medicare inpatient hospital care, ambulatory care, health plans, and postacute care. Currently, there are eight VBP programs in Medicare, with two post-acute care programs in proposal or planning:

- Hospital Readmission Reductions Program

- Hospital-Acquired Condition Payment Reduction

- Hospital Value-Based Purchasing

- Medicare Shared Savings Program

- Physician Value-Based Modifier

- End-Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Program

- Medicare Advantage/Part C1

- Medicare Part D1

- Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing (in planning)

- Home Health Value-Based Purchasing (in planning)2

Improving Value-Based Payment to Address Unintended Consequences

While the impact of VBP strategies on providers serving vulnerable populations and on health disparities continues to be monitored both under Medicare and more widely, and because more VBP programs are being implemented and existing programs are expanding, some methods have been proposed to improve these payment programs to address the potential unintended consequences on vulnerable populations and disparities. Chief among methods to improve VBP to address these unintended consequences is accounting for differences in patient characteristics when measuring quality and calculating payments, sometimes referred to as risk adjustment or payment adjustment. Most emerging VBP strategies recognize that differences in patient characteristics may affect health care outcomes and costs independently of variations in the provision of care, and that these must be accounted for when measuring quality and calculating payments (Rosenthal, 2008). Currently, patient characteristics included in these adjustments typically only include certain demographic and clinical characteristics (e.g., age, sex, and clinical comorbidities).

Accounting for Social Risk Factors in Value-Based Payment

The primary method proposed to account for social risk factors in value-based payment has been to include them in risk adjustment of performance measures used as the basis for payment. Risk adjustment primarily aims to improve measurement accuracy, such as for the purposes of quality assessment and public reporting, but becomes a method of payment adjustment when measures that are risk adjusted are used as the basis for payment. In this context, proposed adjustments have implications for health equity and fairness of provider reimbursement, and the proposal has become controversial.

Critics of including social factors in risk adjustment argue that what may appear as differences by social groups may be genuinely attributed to quality differences and not the social factors themselves. In this case adjusting for the social factor would obscure genuine disparities

_______________

1 The committee included Medicare Part C and Part D because the study sponsor, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation of the Department of Health and Human Services, included them as relevant payment models in its presentation to the committee at the first meeting (Epstein, 2015), and thus the program is of interest to them. Additionally, the committee considers Part C and Part D to have important design features through which quality and cost performance affect payment and market share. As described in more detail in Chapter 1, Part C and Part D are both risk-sharing models of payment, which necessitates consideration of risk adjustment for the capitation amount or global spending target, and also include other value-based payment mechanisms, such as bonus payments (Part C) and risk corridors (Part D).

2 This report does not discuss innovation models conducted under the CMS Innovation Center and other demonstration programs, such as the Maryland all-payer model, the Nursing Home Value-Based Purchasing Demonstration, and the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative.

and make it more difficult to hold those providing lower-quality care accountable (Jha and Zaslavsky, 2014; Kertesz, 2014; Krumholz and Bernheim, 2014; O’Kane, 2015). They further argue that so doing implicitly accepts a lower standard for vulnerable patients (Bernheim, 2014; Jha and Zaslavsky, 2014). This would not only enable lower-quality care for disadvantaged persons, but it would also reduce incentives for improvement (Bernheim, 2014; Kertesz, 2014).

Proponents argue that certain social factors lie outside the control of providers and thus hospitals should not be accountable for them (Jha and Zaslavsky, 2014; Joynt and Jha, 2013; Pollack, 2013; Renacci, 2014). In this way of thinking, social factors are confounders masking true performance and adjusting for them provides more accurate measurement (Fiscella et al., 2014; Jha and Zaslavsky, 2014). If this is the case, risk adjusting for social factors would ensure that hospitals are being fairly assessed and that providers caring for more disadvantaged patients are not punished precisely for caring for these patients (Girotti et al., 2014). Indeed, if serving disadvantaged patients results in disproportionate penalties, this may disincentivize providers from caring for them (Joynt and Jha, 2013). Others also raise concerns that because disproportionate penalties will further reduce the already limited resources of providers serving greater shares of disadvantaged patients with even fewer financial resources, quality in these providers will likely worsen (Grealy, 2014; Ryan, 2013), and the organizations could potentially fail, leaving fewer providers to care for disadvantaged patients (Lipstein and Dunagan, 2014). In both cases, this would widen disparities.

In light of this debate, two expert panels have previously examined whether to include social risk factors in risk adjustment for Medicare payment models and offered recommendations. In its June 2013 Report to the Congress, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) recommended that CMS use two methods of adjustment, one for public reporting (i.e., quality measurement) and another for financial incentives. Readmissions rates for public reporting would remain unadjusted for socioeconomic disparities so as not to mask potential disparities in quality of care. However, when calculating penalties, hospitals would be compared not to all other hospitals as is currently done, but to hospitals with a similar patient mix (MedPAC, 2013). In 2014, an expert panel convened by the National Quality Forum (NQF) released a technical report reversing the NQF’s previous position to exclude “sociodemographic factors”3 in risk-adjustment of performance measures used in “accountability applications” (i.e., as a basis of payment or public reporting). The panel recommended that sociodemographic factors should be included in risk adjustment if there is a conceptual relationship between a given factor and specific quality metrics as well as empirical evidence of that association (NQF, 2014).

Congress has also taken up the issue. While authorizing the establishment of several VBP programs in Medicare, the IMPACT Act also required that the Secretary of Health and Human Services submit a report to Congress by October 2016 that assesses the impact of SES on quality and resource use in Medicare using measures such as poverty and rurality from existing Medicare data. It also required a report to Congress by October 2019 on the impact of SES on quality and resource use in Medicare using measures (e.g., education and health literacy) from other data sources. It also required qualitative analysis of potential SES data sources and Secretarial recommendations on obtaining access to necessary data on SES and accounting for SES in determining payment adjustments (Epstein, 2015).

_______________

3 Sociodemographic factors are defined as a “variety of socioeconomic (e.g. income, education, occupation) and demographic factors (e.g. age, race, ethnicity, primary language.”

As input to the analyses to be included in the 2016 and 2019 reports to Congress, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), acting through the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, asked the IOM to convene an ad hoc committee to provide a definition of SES for the purposes of application to Medicare quality measurement and payment programs; to identify the social factors that have been shown to impact health outcomes of Medicare beneficiaries; and to specify criteria that could be used in determining which social factors should be accounted for in Medicare quality measurement and payment programs. Further, the committee will identify methods that could be used in the application of these social factors to quality measurement and/or payment methodologies. Finally, the committee will recommend existing or new sources of data and/or strategies for data collection. The committee’s work will be conducted in phases and produce five brief reports (see Box 1-1 in Chapter 1). In this first report, the committee will focus on the definition of SES and other social factors that have been shown to influence health outcomes of Medicare beneficiaries, as reflected in current Medicare payment and quality programs.

The statement of task for this report includes several key words that drove the committee’s work. The task refers to identifying “SES factors” that “have been shown” to “impact” “health outcomes” of “Medicare beneficiaries.” This project is intended to provide very practical and targeted input to HHS and Congress as they consider whether to adjust Medicare payment programs for social risk factors. This project builds on decades of research assessing the social determinants of health; it does not reinvent or redefine that field of scholarship. The committee is narrowly focused on how social risk factors affect health care use and outcomes of a specific group of people—Medicare beneficiaries—in response to encounters with the health care system, not how social factors affect health status generally.

The committee identified five social risk factors that are conceptually likely to be of importance to health outcomes of Medicare beneficiaries:

- Socioeconomic position;

- Race, ethnicity, and cultural context;

- Gender;

- Social relationships; and

- Residential and community context.

Although an independent risk factor and not a social factor, the committee included health literacy as another important factor.

Although the statement of task specifies only examining the impact of these social risk factors on “health outcomes,” it also specifies that the social risk factors should be targeted “for the purpose of application to quality, resource use, or other measures used for Medicare payment programs.” Thus, given the importance that Medicare VBP programs have placed on this broader set of measures and given that Medicare applies these measures when calculating payments, the committee interpreted “health outcomes” as encompassing measures of health care use, health care outcomes, and resource use. Hence, the committee included the following domains of measures: health care utilization, clinical processes of care, health (clinical care) outcomes, patient experience, patient safety, and cost.

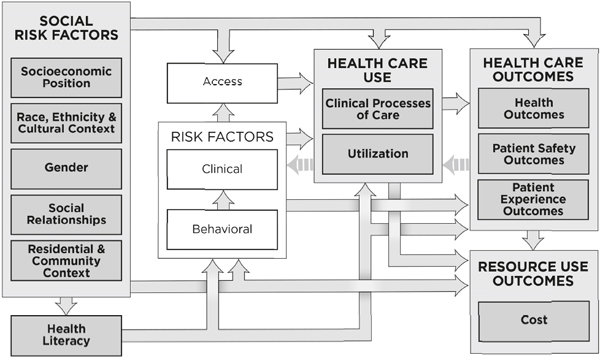

Figure S-1 illustrates the committee’s conceptual framework, which illustrates the primary hypothesized relationships by which social risk factors may affect the broad set of health outcomes at issue. The framework is not intended to illustrate the entire universe of potential causes and risks. The framework applies to all Medicare beneficiaries, including disabled beneficiaries and beneficiaries with ESRD, because although the committee acknowledges that the Medicare population is heterogeneous (even among beneficiaries age 65 and older), the committee expects the effect of social risk factors to be similar for all Medicare subpopulations (beneficiaries with disabilities, those with ESRD, and older adults). The committee will revisit this assumption in subsequent reports. Additionally, Medicare coverage and the measures used to assess health care quality and outcomes do not differ for Medicare beneficiaries by origin of entitlement, except for certain measures of ESRD care and outcomes, and thus the health outcomes in the framework are also equally applicable.

Current Medicare quality measures fall within each of the domains embraced by the committee in the expanded definition of “health outcomes.” Table S-1 contains examples of Medicare quality measures currently in use in each of the health care use and outcome domains embraced by the committee in the expanded definition of “health outcomes.”

COMMITTEE PROCESS AND OVERVIEW OF THIS REPORT

The committee comprises expertise in health disparities, social determinants of health, risk adjustment, Medicare programs, health care quality, health system administration, clinical medicine, and health services research. The committee will meet five times over 12 months and issue five brief, consensus reports. In this report, the committee outlines a conceptual framework for how social risk factors could influence health care outcomes and quality measures of relevance to Medicare programs. The committee then presents the results of a literature search to identify those social risk factors that have been shown to influence broad categories of relevant health care outcomes and quality measures. The relevant literature is described generally without an assessment of the quality of each individual study and with no attempt at data integration, such as in a meta-analysis. The identification and description of the literature should not be mistaken for a systematic review that uses a formal system for weighing and describing evidence, such as those used in clinical or public health guideline development. In its findings, the committee uses the term “influence” to describe an association between a social risk factor and a health care use or outcome measure without implying a causal association. Future work of the committee will address the question of whether a specific social factor could be incorporated into Medicare payment programs, the methods to do so, and data needs to accomplish the task.

DEFINITIONS AND FINDINGS FROM THE LITERATURE SEARCH

In this section, the committee defines each of the five social factor domains, as well as health literacy, and summarizes the results of the literature search linking effects of each domain on health care outcomes and quality measures.

FIGURE S-1 Conceptual framework of social risk factors for health care use, outcomes, and cost.

NOTE: This conceptual framework illustrates primary hypothesized conceptual relationships.

TABLE S-1 Health Care Use and Outcome Domains and Example Medicare Quality Measures

| Health Care Use or Outcome Domain | Example Medicare Quality Measures |

| Health Care Use | |

| Clinical Processes of Care |

|

| Utilization |

|

| Outcomes | |

| Resource Use (Costs) Health (Clinical Care) |

|

| Patient Safety |

|

| Patient Experience |

|

NOTE: AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; AMI = acute myocardial infarction; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Socioeconomic Position

Socioeconomic position (SEP) is an indicator of an individual’s absolute and relative position in a socially stratified society. SEP captures a combination of access to material and social resources as well as relative status, meaning prestige- or rank-related characteristics, and is commonly measured through indicators such as income and wealth (with wealth being of special relevance in older individuals), education, and occupation (including occupational history and employment status). To that end, the committee employs the term socioeconomic position, rather than the more commonly used phrase socioeconomic status, because socioeconomic status blurs distinctions between two different aspects of socioeconomic position (actual resources and status) and privileges status over actual resources (Adler et al., 1994; Krieger et al., 1997; Lynch and Kaplan, 2000). SEP over one’s lifetime is a powerful predictor of many health-related processes and outcomes and is often related to outcomes in a dose–response manner. In the medical field, insurance status is also used as a proxy for SEP—for example, dual Medicare–Medicaid eligibility among the Medicare population is often used as a proxy for low income. However, insurance status is generally a very imperfect proxy, because (1) it does not capture the continuum of SEP, (2) it may capture dimensions of health status unmeasured by other data sources, and (3) because it represents insurance status itself, which is distinct from SEP. The committee made the following findings:

- The committee identified literature indicating that income may influence health care utilization, clinical processes of care, costs, health outcomes, and patient experience.

- The committee identified literature indicating that when measured by a proxy of insurance status, income may influence health care utilization, clinical processes of care, and patient experience.

- The committee identified literature indicating that education may influence health care utilization, health outcomes, and patient experience.

- The committee identified literature indicating that occupation may influence health care utilization, health outcomes, and patient experience.

- The committee identified no literature indicating that socioeconomic position may influence patient safety outcomes.

Race, Ethnicity, and Cultural Context

Race and ethnicity are another key social factor. Race and ethnicity are dimensions of a society’s stratification system by which resources, risks, and rewards are distributed. As such, racial and ethnic categories capture a range of dimensions relevant to health, especially those related to social disadvantage (IOM, 2014a; Williams, 1997). These dimensions include access to key social institutions and rewards; behavioral norms and other sociocultural factors; inequality and injustice in the distribution of power, status, and material resources; and psychosocial exposures such as discrimination (Williams, 1997). It is well established that race and ethnic background is often predictive of health care and health outcomes even after accounting for such traditional measures of SEP as income and education (Krieger, 2000; LaVeist, 2005; Williams, 1999; Williams et al., 2010).

A number of factors likely contribute to this “independent” effect of race and ethnicity including

- lack of comparability of a given SEP measure across race/ethnic groups (e.g., income returns to education are well known to vary by race, and income is differentially correlated with wealth by race);

- importance of other exposures such as neighborhood environments that are pattered differently by race even among individuals of apparently similar SEP;

- the importance of race or ethnic specific factors such as discrimination and immigration related factors, including time living in the United States and language proficiency; and

- measurement error in SEP.

Although race and ethnicity reflect many different social circumstances, there can also be important heterogeneity in health within race and ethnic groups, driven for example by SEP heterogeneity or heterogeneity in English language proficiency, country of origin, time in the United States, or other cultural dimensions. The committee made the following findings:

- The committee identified literature indicating that race and ethnicity may influence health care utilization, clinical processes of care, costs, health outcomes, patient safety, and patient experience.

- The committee identified literature indicating that language may influence health care utilization, clinical processes of care, health outcomes, and patient experience.

- The committee identified literature indicating that nativity may influence clinical processes of care and patient experience.

Gender

Gender is known to be related to many health and health care–related outcomes. The committee used the term gender broadly to capture the social dimensions of gender and distinguish these from biological effects of sex. Gender is known to affect a number of health outcomes as well as interactions with the health care system, health care–related processes, and outcomes of health care. Gender or sexual minorities, including individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, and questioning, may also experience differences in health and health care. These disparities may be related to exposure to stigma, discrimination, and violence on the basis of their non-normative identity; barriers to accessing health care, including fear of discrimination from providers; and unhealthy behaviors, especially increased rates of smoking, alcohol use, and substance (IOM, 2011). The committee made the following finding:

- The committee identified literature indicating that gender may influence clinical processes of care and patient experience.

Social Relationships

Social relationships are another important social risk factor. It is well established that many dimensions of social relationships including access to social networks that can provide access to resources (including material and instrumental support) as well as the emotional support available through social relationships can be important to health (Berkman and Glass, 2000; Cohen, 2004; Eng et al., 2002; House et al., 1988). Likewise, social isolation and

loneliness have been shown to have important consequences for health (Berkman and Glass, 2000; Brummett et al., 2001; Cohen, 2004; Eng et al., 2002; House et al., 1988; Wilson et al., 2007). Social relationships may be of special importance to health care access, process and outcomes among older individuals (Cornwell and Waite, 2009; Hawton et al., 2011; Seeman et al., 2001; Tomaka et al., 2006) and persons with ADL and IADL limitations (AARP Public Policy Institute, 2010). Social relationships are most frequently assessed in the health care and health services research literature with three constructs: marital status, living alone, and social support. The committee made the following findings:

- The committee identified literature indicating that marital status may influence health care utilization, clinical processes of care, costs, health outcomes, and patient experience.

- The committee identified literature indicating that social support may influence heath care utilization, clinical processes of care, health outcomes, and patient experience.

- The committee identified literature indicating that living alone may influence health care utilization, clinical processes of care, and health outcomes.

- The committee identified no literature indicating that social relationships may influence patient safety.

Residential and Community Context

The committee uses the term community context to refer to a set of broadly defined characteristics of residential environments that could be important to health and the health care process and its outcomes. Dimensions include the physical environments (e.g., housing, walkability, transportation options, and proximity to services) as well as the social environment (e.g., safety and violence, social disorder, presence of social organizations, and social cohesion) (Diez Roux, 2001; Diez Roux and Mair, 2010). Community context also references the policies, infrastructural resources and opportunity structures that influence individuals’ everyday lives. The SEP or racial and ethnic composition of an area is sometimes used as a proxy for some of these attributes, although it is an imperfect proxy and can also capture unmeasured or imperfectly measured individual-level SEP. Community context may also have special relevance for older persons owing to decreases in mobility with age and for persons with mobility disabilities (Yen et al., 2009). The committee made the following findings:

- The committee identified literature indicating that community composition may influence health care utilization, clinical processes of care, health outcomes, and patient safety.

- The committee identified literature indicating that community context may influence health care utilization, health outcomes, and patient experience.

- The committee identified literature indicating that urbanization may influence health care utilization, clinical processes of care, costs, and patient experience.

Health Literacy

Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions (NASEM, 2015). Although an individual risk factor and not a social factor, the

committee includes health literacy in the framework, because it is specifically mentioned in the IMPACT Act, and is thus of interest to Congress, is affected by social risk factors, and because the literature supports a role for health literacy in health care outcomes and quality measures. The committee also included the related concept of numeracy, the ability to understand information presented in mathematical terms and to use mathematical knowledge and skills in a variety of applications across different settings (IOM, 2014b). The committee made the following finding:

- The committee identified literature indicating that health literacy may influence health care utilization, clinical processes of care, cost, and patient experience.

What is clear at this point is that health literacy and social risk factors (SEP; race, ethnicity, and cultural context; gender; social relationships; and residential and community context) have been shown to influence health care use, costs, and health care outcomes in Medicare beneficiaries. However, some specific factors were found not to influence one or more outcomes. The committee has not yet evaluated the literature for the purpose of identifying the factors that could be incorporated into measures used in Medicare payment programs; that is the focus of the third report from the committee.

AARP Public Policy Institute. 2010. Trends in family caregiving and paid home care for older people with disabilities in the community: Data from the national long-term care survey. http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/ppi/ltc/2010-09-caregiving.pdf (accessed December 7, 2015).

Adler, N. E., T. Boyce, M. A. Chesney, S. Cohen, S. Folkman, R. L. Kahn, and S. L. Syme. 1994. Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. American Psychologist 49(1):15–24.

Berkman, L., and T. Glass. 2000. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bernheim, S. M. 2014. Measuring quality and enacting policy: Readmission rates and socioeconomic factors. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 7(3):350–352.

Brummett, B. H., J. C. Barefoot, I. C. Siegler, N. E. Clapp-Channing, B. L. Lytle, H. B. Bosworth, R. B. Williams, Jr., and D. B. Mark. 2001. Characteristics of socially isolated patients with coronary artery disease who are at elevated risk for mortality. Psychosomatic Medicine 63(2):267–272.

Cohen, S. 2004. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist 59(8):676–684.

Cornwell, E. Y., and L. J. Waite. 2009. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 50(1):31–48.

Diez Roux, A. V. 2001. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. American Journal of Public Health 91(11):1783–1789.

Diez Roux, A. V., and C. Mair. 2010. Neighborhoods and health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1186:125–145.

Eng, P. M., E. B. Rimm, G. Fitzmaurice, and I. Kawachi. 2002. Social ties and change in social ties in relation to subsequent total and cause-specific mortality and coronary heart disease incidence in men. American Journal of Epidemiology 155(8):700–709.

Epstein, A. 2015. Accounting for socioeconomic status in medicare payment programs: ASPE’s work under the IMPACT Act. Presented to the Committee on Accounting for Socioeconomic Status in Medicare Payment Programs, Washington, DC, October 6, 2015.

Fiscella, K., H. R. Burstin, and D. R. Nerenz. 2014. Quality measures and sociodemographic risk factors: To adjust or not to adjust. Journal of the American Medical Association 312(24):2615–2616.

Girotti, M. E., T. Shih, S. Revels, and J. B. Dimick. 2014. Racial disparities in readmissions and site of care for major surgery. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 218(3):423–430.

Grealy, M. R. 2014. Measure under consideration (MUC) comments: Letter to the National Quality Forum: Healthcare Leadership Council, December 5, 2014. http://www.hlc.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/06/HLC_Early-Public-Comment-on-Measures-Under-Consideration.pdf (accessed October 30, 2015).

Hawton, A., C. Green, A. P. Dickens, S. H. Richards, R. S. Taylor, R. Edwards, C. J. Greaves, and J. L. Campbell. 2011. The impact of social isolation on the health status and health-related quality of life of older people. Quality of Life Research 20(1):57–67.

House, J. S., K. R. Landis, and D. Umberson. 1988. Social relationships and health. Science 241(4865):540–545.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2014a. Capturing social and behavioral domains and measures in electronic health records: Phase 2. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2014b. Health literacy and numeracy: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jha, A. K., and A. M. Zaslavsky. 2014. Quality reporting that addresses disparities in health care. Journal of the American Medical Association 312(3):225–226.

Joynt, K. E., and A. K. Jha. 2013. A path forward on Medicare readmissions. New England Journal of Medicine 368(13):1175–1177.

Kertesz, K. 2014. Center for Medicare Advocacy comments on the impact of dual eligibility on MA and Part D quality scores. http://www.medicareadvocacy.org/center-for-medicare-advocacy-comments-on-the-impact-of-dual-eligibility-on-ma-and-part-d-quality-scores (accessed October 30, 2015).

Krieger, N. 2000. Refiguring "race": Epidemiology, racialized biology, and biological expressions of race relations. International Journal of Health Services 30(1): 211-216.

Krieger, N., D. R. Williams, and N. E. Moss. 1997. Measuring social class in us public health research: Concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annual Review of Public Health 18:341–378.

Krumholz, H. M., and S. M. Bernheim. 2014. Considering the role of socioeconomic status in hospital outcomes measures. Annals of Internal Medicine 161(11):833–834.

LaVeist, T. A. 2005. Disentangling race and socioeconomic status: A key to understanding health inequalities. Journal of Urban Health 82(2 Suppl 3):iii26-34.

Lipstein, S. H., and W. C. Dunagan. 2014. The risks of not adjusting performance measures for sociodemographic factors. Annals of Internal Medicine 161(8):594–596.

Lynch, J., and G. Kaplan. 2000. Socioeconomic position. In Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press.

MedPAC (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission). 2013. Chapter 4: Refining the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. In Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system. Washington, DC: MedPAC.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2015. Health literacy: Past, present, and future: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

NQF (National Quality Forum). 2014. Risk adjustment for socioeconomic status or other sociodemographic factors. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum.

O’Kane, M. 2015. Comment on the advance notice of methodological changes for calendar year 2016 for Medicare Advantage call letter.

https://www.ncqa.org/PublicPolicy/CommentLetters/MedicareAdvantage032015.aspx (accessed November 3, 2015).

Pollack, R. 2013. CMS-1599-p, Medicare Program; hospital inpatient prospective payment systems for acute care hospitals and the long-term care hospital prospective payment system and proposed fiscal year 2014 rates; quality reporting requirements for specific providers; hospital conditions of participation; Medicare Program; proposed rule (vol. 78, no. 91): Letter to the CMS Administrator Tavenner. http://www.aha.org/advocacy-issues/letter/2013/130620-cl-cms-1599p.pdf (accessed October 30, 2015).

Renacci, J. B. 2014. Letter to HHS Secretary Burwell and CMS Administrator Tavenner regarding the Medicare Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. http://tinyurl.com/q6shyoc (accessed October 30, 2015).

Rosenthal, M. B. 2008. Beyond pay for performance—Emerging models of provider-payment reform. New England Journal of Medicine 359(12):1197–1200.

Ryan, A. M. 2013. Will value-based purchasing increase disparities in care? New England Journal of Medicine 369(26):2472–2474.

Seeman, T. E., T. M. Lusignolo, M. Albert, and L. Berkman. 2001. Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: Macarthur studies of successful aging. Health Psychology 20(4):243–255.

Tomaka, J., S. Thompson, and R. Palacios. 2006. The relation of social isolation, loneliness, and social support to disease outcomes among the elderly. Journal of Aging and Health 18(3):359–384.

Williams, D. R. 1997. Race and health: Basic questions, emerging directions. Annals of Epidemiology 7(5):322–333.

Williams, D. R. 1999. Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 896:173-188.

Williams, D. R., S. A. Mohammed, J. Leavell, and C. Collins. 2010. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: Complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1186:69-101.

Wilson, R. S., K. R. Krueger, S. E. Arnold, J. A. Schneider, J. F. Kelly, L. L. Barnes, Y. Tang, and D. A. Bennett. 2007. Loneliness and risk of alzheimer disease. Archives of General Psychiatry 64(2):234–240.

Yen, I. H., Y. L. Michael, and L. Perdue. 2009. Neighborhood environment in studies of health of older adults: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 37(5):455–463.

This page intentionally left blank.