3

Organizational Strategies and Processes for Enhancing U.S. Air Force Communication Effectiveness

The foregoing chapters of this report have outlined the rationale for developing a communication strategy for the U.S. Air Force (USAF) and the challenges in doing so, given the wide diversity of the missions and audiences that the Air Force must address. This chapter will explore specific elements of a possible strategy for increasing the effectiveness of USAF communication, with a particular focus on social media. Lessons learned by other large organizations that have faced comparable issues will be presented.

LESSONS LEARNED BY OTHER ORGANIZATIONS

Several professional communicators from major corporations and communication consulting firms briefed the workshop participants on best practices used by their organizations and lessons they have learned through their experiences. These presentations and discussions are summarized in this section, with each lesson learned followed by the discussion around that topic.

Responsibility of Communication Within an Organization

As presented by several participants, communication is everyone’s responsibility in an organization, and that responsibility begins with leadership. Mr. Brian Ames said that Boeing’s strategies “drive a value chain seeking to connect communications with organizational performance.” They outline specific communications roles for executives, managers, and the workforce. In addition, Boeing’s “strategic measurement” of communication is tied to its semi-annual engagement metrics, which are used, in part, to determine management rewards, he said.

Dr. Brian Hoey gave several examples of good organizational communication practices. For example, when NASA has a public relations issue, it puts scientific, management, and public affairs people together in a room and identifies the best spokespeople on that issue.

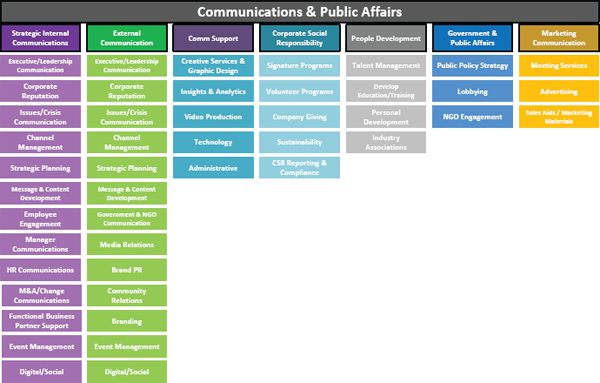

In talking about what the C-suite (senior leadership) wants from the communications function today, Mr. Peter Debreceny of Gagen-MacDonald noted that many communication leaders are not sufficiently versed in the business aspects of what makes the organization succeed. Mr. Debreceny described the typical taxonomy of a corporate communications and public affairs department today, a unit that is responsible for executing all communication and is typically at the level of all other key corporate functions such as marketing and sales or human resources (see Figure 3-1).

FIGURE 3-1 Organization of a typical corporate communications and public affairs office. SOURCE: Peter Debreceny, Gagen-MacDonald, “Strategic Internal Communications: The Current State.” Courtesy of Gagen-MacDonald, copyright 2015.

Organizational Vision and Core Values

Several participants discussed the importance for an organization’s vision and core values to be simple and universally understandable. Ms. Jennie Bledsoe, director of global internal communications for the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company noted, as other participants had, the importance of emphasizing not only the what in communication but also the why.

As an example of the need to be flexible in communicating an organization’s core values, Mr. William Power of Fleishman-Hillard described how IBM shifted its corporate image from that of a technology company, a builder of computers, to an “e-business,” which means that “IBM understands business. We use internet technology as a tool to transform key business processes and help companies succeed.”

Authenticity and Transparency in Communication

Several participants noted that trust is created through face-to-face communication that is both authentic and transparent. In an example of a company merger described by Dr. Hoey, managers helped to overcome resistance and fear on the part of employees by frequent contact (“managing by walking around”). Through frequent travel and teleconferences, they overcame the potential for misalignment of priorities between the two sets of executives. Mr. Debreceny recounted a merger between two companies in which the two communication teams merged to develop a communication strategy 6 months before the merger was publicly announced. Senior executives in both organizations led the strategy development. Ms. Bledsoe agreed with the frequently expressed commentary

that the direct supervisor/manager—what Mr. Debreceny referred to as a “line-of-sight” manager—is “the critical link” between corporate and the employee.

“Leaders need to be open about being open,” Dr. Hoey said. It is essential to be aware of the concerns of employees. “If you can’t be transparent, at least be translucent,” he advised. Identify key “influencers” not in the chain of command to help develop strategy, Dr. Hoey suggested. Ms. Wendi Strong noted that USAA’s leaders meet with such influencers regularly to brief them on changes in management and policy. Mr. Ed Brill stated that one key to deep penetration of social media into IBM’s overall communications is that it strives for transparency in corporate messaging—clarity about company policies and practices—something that has led to employee trust. An authentic voice combined with transparency is a huge corporate shift in internal communication, and it has produced employee trust, he said.

Dr. Vernon Miller, associate professor of communication at Michigan State University, focused on the best ways to maintain a high-reliability organization, such as the Air Force. His observations echoed many of the same ones made independently by the other communications experts at the workshop. For example, excellence requires fostering openness in message sending (disclosure) and receiving (receptivity to feedback) at all levels. In addition, passing along information and insight to one’s direct reports is essential in hierarchical organizations. Regarding the negative external communications about which the Air Force is concerned, he said, “If you invite personnel to be engaged in their work, you must enable constructive, upward feedback. Action, receptivity to feedback, and giving feedback can thwart cynicism and malaise among personnel.”

Like the other corporate presenters, Boeing’s Mr. Ames described a largely “employee-centric” communication culture in which credibility on the part of management and respect for the employee are central. “Credibility is everyone’s job,” he said. “But communication is the first-line champion of it.” However, Mr. Ames noted, one of the communication lessons that Boeing is learning is that “credibility with a diverse work force is a journey.”

Organizational Strategy, Culture, and Structure

Participants discussed the importance of aligning strategy, culture, and structure within an organization and highlighted that an organization’s behavior is as equally important as its communications. Part of the openness that is vital for a successful organization today, Dr. Miller said, is a willingness to discuss real strengths and weaknesses of key operations and processes regularly. He noted that the USAF selects intelligent, capable volunteers and introduces them to USAF core values through onboarding experiences in basic training. However, the most important period of value development, he said, may be during additional skill development training and in initial unit assignments, where the insights of experienced peers can reinforce or undermine the newcomer’s individual development. In his view, “Organizations are always one generation away from extinction. The passing along of values and core knowledge is a necessity, not a luxury.”

In his description of IBM’s shifting its corporate image from computers to e-business, Mr. William Power related that it took a year to educate the workforce about what e-business means. Mr. Power noted that, as part of this education process, IBM conducts “jam sessions,” a blog with a moderator that runs for 24 hours, allowing input from employees around the world. The name itself sounds invigorating and inviting to participants, he said. IBM’s Mr. Brill added that the authentic voice his company has achieved derives from three things: (1) messages are often being written in the first person, (2) weaknesses are disclosed (“not everything is perfect”), and (3) the frequent inclusion of extraneous personal content imparts three-dimensionality.

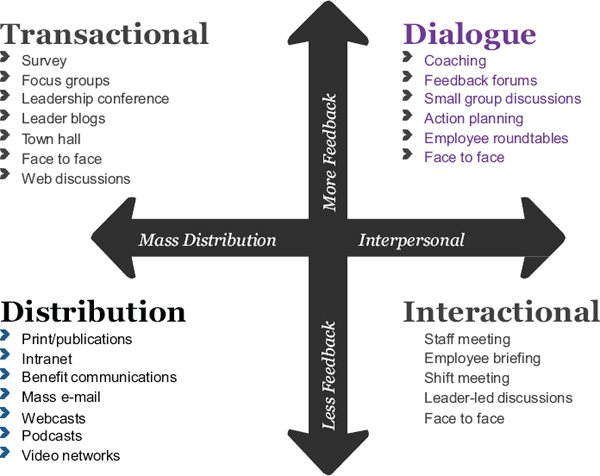

While the fundamentals of communication have not changed, Mr. Debreceny said, there is a difference in the levels of energy and the placement of the emphasis. He pointed out that most of the emphasis now should be on “dialogue,” but “transactional,” “distribution,” and “interactional” communication should still be pursued (see Figure 3-2).

Reaching the Audience

Mr. Debreceny began his presentation with the statement that 85 percent of all organizational digital communications today do not reach the intended recipient. In that context, Mr. Ryan Henary of FedEx Ground spoke

FIGURE 3-2 Elements of communication. SOURCE: Peter Debreceny, Gagen-MacDonald, “Strategic Internal Communications: The Current State.” Courtesy of Gagen-MacDonald, copyright 2015.

about the importance of “tailored messaging”: FedEx Ground tailors communications and tactics by audience, when appropriate. He also recommended asking people what they want to know and how they would like to receive the information—“keep it simple.” A key to their communication strategy is that a simple, unifying message connects FedEx employees worldwide.

For internal social media, Goodyear uses a Microsoft program called Yammer. Because it is inside the company’s firewall, Ms. Bledsoe said, it eased management’s fears about communications potentially being too open. She commented that they addressed its implementation from both the management side and the employee side, giving guidelines to employees regarding what to post and not post and briefing senior managers on the program’s security, uses, and value to the company. Yammer provides a full suite of measurement and analysis tools. The blog is moderated by her staff, and it can search for keywords and alert the moderators to violations of the guidelines. Anonymity is not allowed. Further, if the moderator deletes a post, then it is a “warm delete”; someone from management calls the poster, explains the problem, and helps the person reword the post.

In his presentation, which focused mainly on the use of social media in IBM, Mr. Brill shared four “key takeaways”: (1) there is value in social media, (2) it should focus on objective outcomes, (3) a dedicated strategy is

needed to drive adoption (in which authenticity matters), and (4) the best available communication technologies should be employed throughout the organization.

Communicating with Diverse Audiences

Several participants discussed the importance of tailoring communication channels to audience needs and expectations, both within and across generations. Ms. Bledsoe compared Goodyear’s communication challenges to those of the Air Force: both have diverse employees from different generations at widely dispersed locations, and both use a range of communication tools and technologies to reach these employees. She described the tools that Goodyear currently uses to address these challenges. Among them is a mix of “high touch/high tech channels,” including small-group meetings, toolkits and training for managers (with refreshers for those who display less engagement), a corporate intranet, internal social media, email, both plant and retail newsletters, and advocacy opportunities for their employees.

Maj. Gen. Mari Eder spoke about what she termed “The Millennial Air Force” and the need to “get beyond messaging to a two-way conversation that builds the Air Force narrative.” She described a number of examples of the different ways in which this generation is fluent in communicating using social media and other technologies. For example, she presented that, as of February 2014, a survey showed that 55 percent of American Millennials reported having shared a “selfie” on social media. By contrast, 24 percent of Gen-X respondents had done so; 9 percent of Baby Boomers had; and only 4 percent of the Silent Generation (born before 1946) had shared a selfie. Connecting with peers in an authentic way is extremely important to this younger group, and they expect the same authenticity in communication with their employer.

Mr. Brill said that IBM is analogous to the Air Force in being a multi-pronged, global organization. It finds that about 10 percent of its workforce is active in internal digital communications, while only 3 to 4 percent (approximately 15,000 out of a total workforce of 400,000) is active in external digital communication. It sees that those employees who are most active in communicating are the most upwardly mobile and likely to succeed.

The Relationship Between Internal and External Communication

Participants noted that internal communications often escape organizational boundaries and become external communications. Mr. Debreceny stated that the industry communications environment is undergoing a revolution. The smartphone is the main conduit of this change, he said. Messages now come from the bottom up, rather than the top down—something that most top leaders find difficult to manage. Barriers between stakeholders and their audiences have all but disappeared. He agreed with the other presenters that, in this environment, transparency is essential to minimize the potential for misinformation and misinterpretation.

PUTTING SOCIAL MEDIA TO WORK FOR THE AIR FORCE

During discussions on the use of social media within the Air Force, several participants stated that there have been fundamental shifts away from the corporate (Air Force) “push” of information outward to a focus on the employees’ (Airmen) “pull” for information and their own externalization of information, using social media.

Ms. Lois Kelly, chief executive officer of Foghound, presented the concept of the “threateningness” of social media to status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness (SCARF)1 in the military versus the external communication environment. The autonomy issue is particularly important, in her view. The distinction between “issuing information our way” and “sharing information with people” is crucial. Ms. Kelly noted that USAF social media use is missing the story of Air Power2 advocacy, but is doing better with “team belongingness.” Many participants agreed with Ms. Wendi Strong that it is best for management to admit up-front that “social media is scary,” then

_______________

1 Attributed to Dr. David Rock, Your Brain at Work, Harper Business, 2009.

2 The Air Force Basic Doctrine Volume 1, updated February 27, 2015, defines “Air Power” as “the ability to project military power or influence through the control and exploitation of air, space, and cyberspace to achieve strategic, operational, or tactical objectives.”

address what the threatening elements are and how the Air Force can manage them. The participants noted that the message to senior leadership should be, “We have to do this; so here is the best way to go about it.”

Ms. Kelly noted that an organization needs professional analysts to interpret what social media communications mean to that organization. She described “use filters” as a way to prioritize and select which social media channel to use for different purposes. For example, one of the most important uses of social media is for dealing with a crisis (e.g., breaking news). Ms. Kelly said that Twitter is the best channel for use in these situations. She suggested using scenario planning for crisis situations to help stay in front of the story.

Goodyear’s Ms. Bledsoe related that she had hired a young “reverse mentor” to explain the Millennial generation’s views and communication practices to her. IBM’s Mr. Brill described their “New2Blue” social community of new hires (mostly Millennials); the rest of IBM “watches” them online to learn about them as well as from them. Mr. Debreceny noted that IBM has encouraged every employee to become a social media advocate, but first one has to agree to undergo training. Mr. Brill said that his company has formal social computing guidelines that provide employees with both permission and direction for social communicating; and they all must take a 2-hour course every year to recertify for security issues. Mr. Ed Terpening of the Altimeter Group said that corporate training tends to focus on what not to do. He suggested that more guidance is needed for Airmen on “judgment training—that is, what they can do.”

Mr. Terpening was asked, “How do you assess an organization’s readiness for social media?” He replied that the starting point is research. They take diagnostic information and put it into the context of the client, often using case studies. Gen. Douglas Fraser commented that this is not unlike introducing any new program—there is a need for change in management, training, and guidance.

The committee asked, “What does a successful strategy look like?’ Ms. Kelly replied that there are three things to know and do:

- Identify the desired outcomes in terms of perception and behavioral goals. How do you communicate in new ways to affect perception and behavioral goals using social media?

- Build a “predictive analytics capability” based on measurement that uses analyses of past and current use trends on a specific social media platform to forecast future use patterns.

- Consider the complexity of new technologies. Internal communication based on social media “needs to be easy, blessed with authority . . . and there are privacy issues.”

Ms. Strong noted that one of the true benefits of social media is that it can be measured—real time—using analytical tools. Soon, most organizations will be able to use these “analytics” and social media metrics in a predictive way. Gen. Fraser commented that analytics remove the fear that “I’m not able to control my message as I go into social media.” Accenture Digital’s Mr. Robert Harles added that the predictive element not only helps keep the organization safe, but also tells leadership what they need to know in order to achieve the desired outcomes. It tells them how to fit the message into what decision makers and influencers are thinking, as well as how they are obtaining and using information.

Mr. Harles suggested thinking about social media not only as communication, but also as a strategic element, “allowing you to understand the things going on around you, understand the people you need to recruit, and in general understand how Air Force people are getting their information and using it.” Benefits can be unexpected. For example, Mr. Brill reported that at IBM they find that those employees more actively engaged in internal social media are the best innovators and are “120 percent” more likely to generate innovation.

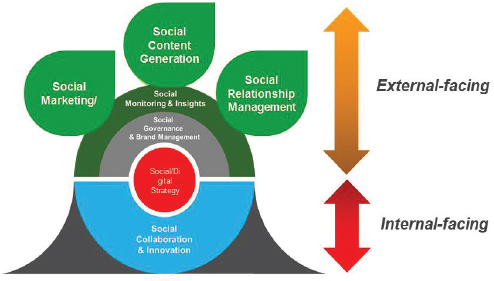

Gen. Fraser summarized this part of the discussion: “Social media with predictive analytics will give me the information I need to understand the world in which I’m trying to navigate. Without it, I’m flying blind. “Mr. Harles added, “You can’t not do this. It’s going to happen—and already is—whether you get involved in it or not. You need to build the social enterprise into the organization and make it strategic” (see Figure 3-3).

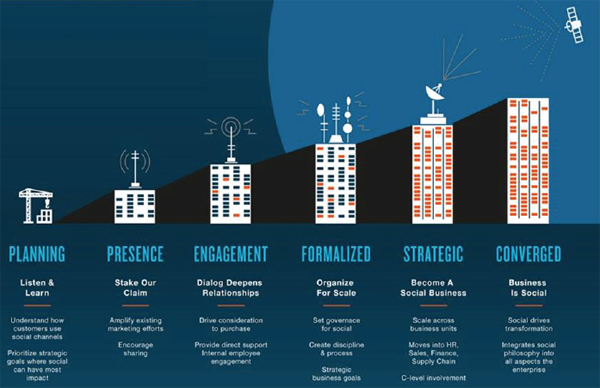

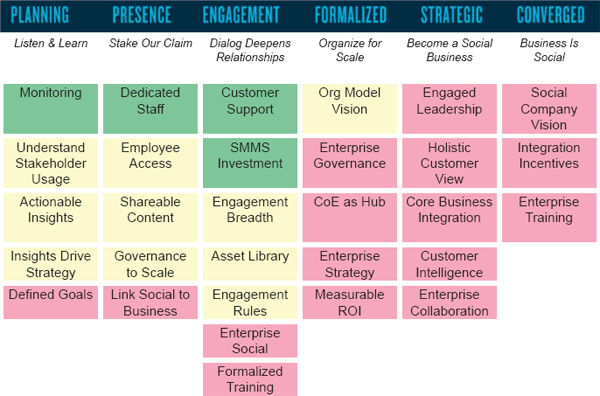

Mr. Terpening described six stages of “social business transformation” (Figure 3-4). His assessment is that the Air Force is somewhere in the “engagement” stage, working toward the “formalized” and “strategic” levels.

Figure 3-5 describes ways of measuring the six stages. In Mr. Terpening’s view, the Air Force meets the requirements shown in green, at least for the current level of maturity. It partially meets the requirements indicated

FIGURE 3-3 Embedding social media into an organization. SOURCE: Robert Harles, Social & Collaboration, Accenture Interactive, “Building the Social Enterprise: US Air Force.” Courtesy of Accenture Interactive.

FIGURE 3-4 Stages in the transformation of an organization and integration of social media. SOURCE: Ed Terpening, Industry Analyst, Altimeter Group, “Social Media Industry Research & Insights to Inform Advanced USAF Strategy.” Courtesy of Altimeter Group, copyright 2015.

FIGURE 3-5 Six stage maturity and readiness approach to measuring organizational progress toward implementing social media. SOURCE: Ed Terpening, Industry Analyst, Altimeter Group, “Social Media Industry Research & Insights to Inform Advanced USAF Strategy.” Courtesy of Altimeter Group, copyright 2015.

in yellow, but more work is needed there. Those shown in red need significant attention, he said. Brig. Gen. Kathleen Cook agreed that the Air Force is currently in a transition phase in dealing with social media. It was noted by several participants that an organization does not need to be at the highest level of maturity and instead should determine the appropriate maturity level based on the needs of, and benefits to, the organization.

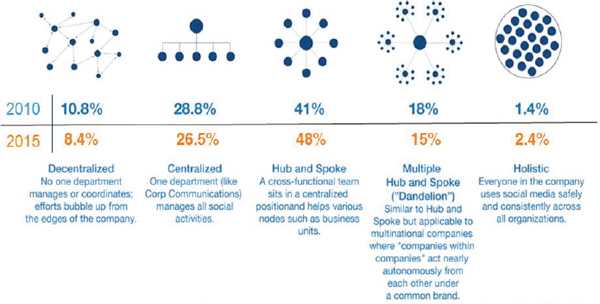

Mr. Terpening’s company prescribes a variety of different social media organizational strategies for different organizations, depending on structure, operations, and needs. For the Air Force, he suggests a “hub-and-spoke” approach (see Figure 3-6). This model is succeeding best for most organizations, he said. In it, a cross-functional team sits in a centralized position and aids various organizational nodes and activities, with all units and all personnel being linked to the USAF social media network.

Many workshop participants recognized that social media will not solve all of the Air Force’s communication problems; however, they are potentially effective tools that have been underutilized. Many of them stated that for greatest effect, social media should be customized to meet the Air Force’s culture and specific needs and implemented in a carefully planned way, utilizing its powerful built-in analytics capabilities, with involvement and oversight by Air Force senior leadership.

Gen. Fraser summarized his reactions to the information presented at the workshop as follows: “The workshop changed my perspective on the value of social media use in an organization—when integrated through a deliberate communications strategy—for enhancing internal communication, for improving workforce collaboration, and for enhancing an organization’s performance.”

FIGURE 3-6 Various organizational models for managing social media. SOURCE: Ed Terpening, Industry Analyst, Altimeter Group, “Social Media Industry Research & Insights to Inform Advanced USAF Strategy.” Courtesy of Altimeter Group, copyright 2015.

Theme 8—Role of Social Media in the Air Force. As noted by Gen. Cook, the USAF does not have a clear policy toward the use of social media, and its use of social media is thus far limited. Many participants noted that internally, social media should be available to all employees to help create a sense of community and connectedness across the diversity of the Air Force while facilitating many core Air Force functions. Externally, they are seen as essential tools for communicating with all audiences and can provide early warning, through analytics, regarding emerging issues and potential conflicts. As Gen. Fraser commented, social media and analytics together can provide the “radar” into the Air Force’s “organizational battlespace” for both internal and external communications. For companies such as IBM, social media have been a driver of innovation. Several participants noted that corporate experience has shown that there will be resistance on the part of senior leadership, but it is essential to engage fully with this new communications reality. Experience has also shown that awareness of the benefits, through training and “reverse mentorship” of senior leaders, will overcome the hesitancy. Formal guidelines and training on what can and cannot be done can reduce the risk of misuse.

POSSIBLE OPTIONS FOR THE USAF IN ORGANIZATION AND PROCESSES

The workshop presentations and discussion with top professional communicators showed that the communication environment within the Air Force has changed in recent years. As Dr. Pamela Drew stated, “There has been a massive shift from the ‘broadcast/push’ corporate-organizational viewpoint to the employee or Airman-centric viewpoint. It has decentralized command and is self-replicating.” Ms. Deborah Westphal said that this is a struggle between control of the message and learning how to live in an environment where there is no control. The challenge, as Dr. Drew pointed out, is to harness that energy through training and, in particular, through the development of a culture of authentic, transparent communication.

Gen. Fraser added “It’s not the people themselves that we’ve lost control of; it’s information. We have to get comfortable with trusting our people to be our best ‘ambassadors.’” He said there is still a chain of command and people are still accountable to the organization, even though they are now passing information along in whatever

way they choose to transmit it. Dr. Drew said that adopting a new approach to communication will work “if you set the rules—that is, ‘If you embarrass the organization you will face consequences.’”

As was repeatedly emphasized by several participants during the workshop, the key management issue with respect to Air Force communication today is that leaders and supervisors need to “take ownership” of communication in all its forms. Leadership, at all levels, matters in enhancing communication.

To give Airmen the information they want regarding policies and decisions, Dr. Hoey recommended providing supervisors and managers with a toolkit—a complete package with briefing materials and other relevant information. However, cautioned Mr. Debreceny, top-level communications require “translation”; they need to be adapted to the user.

As noted previously by some participants, for corporations similar in complexity to the USAF, the responsibility for both internal and external communication is most often held centrally. Execution of communications can occur in a decentralized manner, but only if there is a single point of governance and integration at the highest level. Additionally, many of the participants from industry and academia expressed the view that communications leadership should have a seat at the most senior-level tables and hold senior-level positions commensurate with those of other essential functions.

Lastly, several participants presented information on staffing levels assigned to communication activities. For example, research conducted by Mr. Terpening’s company, Altimeter Group, showed that corporations with more than 50,000 employees typically have about 20 staff assigned to social media alone. Most participants stated that the Air Force communications organization needs to be modernized in terms of organizational structure, processes, and tools and sufficiently staffed and resourced to carry out its modernized functions.