Promoting Food Literacy: Communication Tools and Strategies

“If you want to catch a fish, first learn to think like a fish.”

—R. Craig Lefebvre

“The journey is not to some place [consumers] have not been. The journey is to get them to where they already are.”

—Tom Nagle

Moderated by Wendy Johnson-Askew, Session 3 considered a range of communication and marketing tools and strategies for supporting the public in receiving and embracing scientifically valid information about healthy eating in a way that can lead not only to healthier decisions but also to healthier behaviors. This chapter summarizes the Session 3 presentations and discussion.

To begin the session, Rebecca Ratner, University of Maryland, College Park, explored the effectiveness of guidelines for everyday actions, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) being a prime example. Effective guidelines have two key characteristics, she explained. First, they are memorable, not just immediately after having been exposed but also months later. Second, they are actionable. That is, they are understandable, such that people know what to do and when to do it. Ratner compared the memorability and actionability of the original DGA Food Guide Pyramid, the revised MyPyramid, and the more recent MyPlate; discussed the research that led to MyPlate; and identified key underlying features, such as simplicity, that make a guideline memorable and actionable. Additionally, she stressed the importance of testing messages with target audiences.

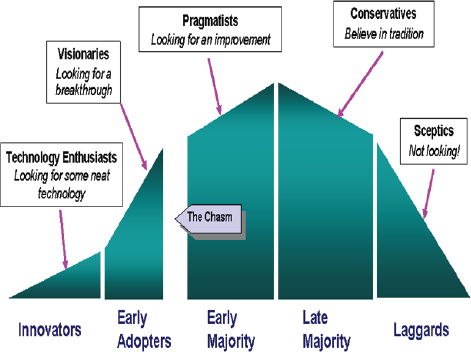

R. Craig Lefebvre, University of South Florida, emphasized the need for researchers to think about population-level interventions, not just individual behavior change interventions, and argued that diffusion theory is a helpful conceptual framework for doing so. He explained that the diffusion-of-innovation model segments the population into innovators, early adopters, the early majority, and laggards, each having different

characteristics and motivations. In his opinion, only when researchers think about the different ways people acquire new behaviors will they be successful in effecting population-level changes with respect to food literacy. He encouraged researchers to go into the field and, rather than confirming a priori hypotheses, tap into people’s shared “mental models.” “If you want to learn how a lion hunts,” he said, “you have to go the jungle, not to the zoo.” Additionally, he emphasized focusing not on the middle of a distribution, which is what researchers typically do, but on the tail ends, that is, the people who are behaving the way one would like them to behave. Focusing on the middle helps describe a problem, he said, but it does not help in understanding how to change behavior. In sum, he said, the question “How can we make practice more science-based?” needs to be turned around. The real question is, “How can we make science more practice-based?”

In her presentation on social norms, Jennifer Bauerle, University of Virginia, echoed the calls of Lefebvre and other speakers to start with the end user or consumer, or, as she put it, meet the audience where they are and say, “Come along with us.” The goal of a social norms approach to changing behavior, she explained, is to reduce the gap between what people are doing and what they think their peers are doing by finding the social norm, holding it up as a mirror, and giving people the space to respond. People learn social norms, such as how to behave when entering an elevator, by watching and listening to other people, she noted. She described the social norms strategy as a positive, inclusive, and empowering approach. In the panel discussion at the end of the session, when asked by moderator Johnson-Askew how a social norms approach could be used to address obesity given that obesity is becoming the norm, Bauerle replied that when the majority of the population is not doing something one wants them to be doing, one should start instead by holding the attitudinal norm up as a mirror (i.e., most people have healthy attitudes) and using it to spur movement on the social norm.

Tom Nagle of Statler Nagler LLC began his presentation by lamenting the very concept of food literacy because it is premised on what he sees as a “wrong-headed” notion that a well-informed citizen will do the right thing—a notion, he argued, that is widely and repeatedly disproved by people’s lifelong behaviors in doing things they know not to be the best or healthiest choices. Elaborating on the complexity of decision making about food alluded to by Sonya Grier (see Chapter 1) and other previous speakers, he observed that people make decisions based on emotions and values, not just rationality and information. He used his company’s “Cans Get You Cooking” marketing campaign as a case study to illustrate how effective messaging does not change people’s values; rather, it puts the desired behavior change in the context of values the consumer already has. Additionally,

he emphasized that effective messaging is not just about the message, but requires what he called a “full marketing architecture.”

In the final presentation of the workshop, Linda Neuhauser, University of California, Berkeley, promoted participatory design as a way to close the gap between the experts who are sending science-based messages about food and nutrition and the consumers who are living complicated lives. As so many other speakers had similarly expressed, she cautioned that communicators will not get far if they fail to engage consumers and learn what they are feeling. Participatory design does just that, she said. She explained that, unlike traditional research, which typically involves defining a single problem and then generating and testing a single solution to that problem, participatory design is a user-centered, iterative process involving the constant and simultaneous defining of problems and generating and testing of ideas. Also unlike traditional research, participatory design involves not the study of what is but the study of being in the future: how to think about the future, how to create that future, and how to evaluate it. Using the “A Cafeteria for Me” project in San Francisco to illustrate effective participatory design, Neuhauser emphasized the importance of thinking big, generating ideas “fearlessly,” and prototyping and testing.

MEMORABLE AND ACTIONABLE HEALTH GUIDELINES1

Ratner’s presentation was based on a 2014 review paper that she and Jason Riis prepared as part of the 2013 Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium titled “The Science of Science Communication II” (Ratner and Riis, 2014). The focus of the article and her presentation was on what makes for an effective health guideline. First, Ratner described what she meant by “guideline.” A guideline, she explained, is information one wants other people—that is, target individuals—to have on actions they need to take repeatedly over time and without having a written checklist in front of them. She clarified that the actions she was talking about were ones that all consumers take every day when making diet-related decisions without consulting a list. Additionally, they are actions that align with what consumers already believe. For example, Ratner said, most people likely believe they should be eating more fruits and vegetables and do not need to be persuaded that this is something they need to do. She explained that the purpose of a guideline is to help them act on that existing belief.

Effective health guidelines have two important features, according to Ratner: (1) memorability and (2) actionability. As she explained, consumers who intend to eat a healthful diet throughout the day need, first, to

______________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Dr. Ratner.

remember what to do (memorability) and, second, be able to actually do it (actionability).

The Memorability and Actionability of the

Dietary Guidelines for Americans

Ratner cited the DGA as an example of a health guideline that was memorable but not actionable when first introduced in 1992. The first DGA was communicated in the form of a food pyramid. Ratner observed that most Americans can remember the gist of that food pyramid. They can remember that it included “horizontal things.” With respect to the parts of and numbers on the pyramid, however, research has shown that the information presented was confusing to consumers. Many did not know what a serving was, for example, or how to interpret the recommended ranges of servings (e.g., “3 to 5 servings”). In fact, Ratner explained, the ranges covered all ages, both sexes, and various levels of exercise. A range of 6 to 11 servings per day, for example, did not mean that an individual should eat between 6 and 11 servings per day. Rather, it meant that some individuals, depending on age, sex, and activity level, should eat 6 servings and others as many as 11.

Based on extensive research, a new DGA, the personalized MyPyramid, was introduced in 2005. To use this guideline, Ratner explained, consumers needed to go to www.mypyramid.gov and enter their age, sex, and typical daily exercise level. Upon entering that information, they would find out precisely how much of each food group they should be eating.

When the MyPyramid DGA was introduced, Ratner and Riis, both trained social psychologists, found it interesting that, despite its being tailored to consumers’ varying sizes, shapes, and ages and being more precise with regard to nutrition, consumers were critiquing the new guideline as being too confusing. She and Riis decided to test, first, MyPyramid’s memorability. Study participants would enter their age, sex, and typical amount of daily exercise and then receive their MyPyramid recommendations based on the entered information. They were asked to study the recommendations well enough so that they would be able to tell them to someone else. Although they were given an unlimited amount of time, the average study time was 30 seconds. Then, just a couple of minutes later, participants were given memory tests and asked to recall what they had just studied. Ratner and Riis found that only one in five participants was able to recall all of the information. When they followed up 1 month later and again asked participants to recall what they had studied, very few people—fewer than 1 percent—were able to recall all the information correctly. “It is a hard task,” Ratner said.

However, the MyPyramid guideline was critiqued more for its lack

of actionability than for its lack of memorability, Ratner recalled. Many consumers did not know, for example, what an ounce was or what an ounce of grain looked like. Consumers also were confused by food items such as pizza and burritos and how to deconstruct them into grains, fruits, vegetables, and other food groups. The most challenging component of the MyPyramid guideline, Ratner explained, was keeping track over the course of a day, for example, of whether one had eaten one’s daily recommended 3½ cups of vegetables. Keeping a running tally is challenging, she said, given what social psychologists know about cognition and memory.

Ratner and Riis set out to see what a more memorable and actionable food and nutrition guideline would look like. They borrowed a plate-based guideline idea from Porter Novelli, a public relations firm in Washington, DC, which had developed the original food pyramid as well as the revised MyPyramid and had been testing plate-based messaging in focus groups. One of the things they liked about plate-based guidelines in terms of actionability was that because most people see plates during meals at least twice per day, the image of plate serves as a “memory trigger” of sorts. Ratner and Riis tested a plate-based guideline that they believed captured one of the more complicated components of MyPyramid. Their half-a-plate guideline instructed individuals to fill half their plate with fruits and vegetables at every meal.

Ratner and Riis conducted a test similar to the one they had used with the MyPyramid guideline. They showed people the half-a-plate guideline, asked them to study it, and then tested their recall both a few minutes later and 1 month later. When participants were tested immediately after studying the guideline, 85 percent were able to recall it. Some people might question why, with such a simple guideline (i.e., fill half your plate with fruits and vegetables at every meal), the recall rate was not 100 percent. Ratner explained that some participants recalled the gist of the guideline (e.g., “eat lots of fruits and vegetables each day”), but not the literal guideline. When the researchers followed up 1 month later, a majority of participants still were able to recall the guideline. Ratner found it interesting that the half-a-plate guideline, being less precise and less comprehensive than the MyPyramid guideline, created all sorts of potential worries with respect to what consumers would put on the other half of the plate, while the MyPyramid guideline was so comprehensive and complete that consumers were unable to absorb it completely. Creating a half-a-plate guideline would require some difficult decisions about which information to omit. Ratner explained that this is an empirical question, one that would require testing to see what people do. For example, are they filling half their plate with fruits and vegetables but the other half with cookies? That would be a problem, Ratner said.

In addition to being memorable, Ratner and Riis found the half-a-plate

guideline to be actionable. People understand what “half” means, Ratner said. It is not as complicated as ounces, and they can see it visually. Also, they do not need to keep a running tally of what they eat over the course of a day. Each meal is a fresh start.

In addition to examining the memorability and actionability of the MyPyramid versus half-a-plate guidelines, Ratner and Riis examined the motivation of consumers to follow the guidelines. They found that overall, the half-a-plate guideline was more motivating than MyPyramid. Even participants who were identified as being interested in nutrition found the MyPyramid guideline complicated and did not really know what to do with it, Ratner noted. In contrast, even people who were identified as not being particularly interested in nutrition were motivated to follow the half-a-plate guideline.

Together, these findings led Ratner and Riis to conclude that the MyPyramid guideline was not, Ratner said, “going to get us where we want to get in terms of consumer behavior change.” The half-a-plate message appeared to be better in many ways.

When the Obama administration decided to revamp the federal government’s food messaging, it reached out to Chip Heath, who knew of Ratner and Riis’s work. As a result, in 2011, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) introduced a plate-based message. It was similar to the plate-based graphic that Porter Novelli had developed several years earlier and sent a more complex message than Ratner and Riis’s half-a-plate graphic. But it was better in many ways than MyPyramid, in Ratner’s opinion, including that it relied on the plate as a visual retrieval cue.

What Makes Guidelines Memorable and Actionable?

Ratner listed several characteristics of memorable and actionable messages. First, messages need to be simple. Examples of simple message are “Got Milk?,” “Stop, drop, and roll,” and “Just do it.” Messages like these have been tested in for-profit settings, and they need to be tested in nutrition settings as well, Ratner argued. She observed that simplicity is important not just because it makes an action more memorable but also because it makes the message less overwhelming and therefore more actionable. She described a study in which she and her colleagues showed one group of people an ad with the message, “How will you stay active today? These running shoes are ready for your toughest workouts every day.” They showed another group the same ad, but it read “toughest workouts every week” instead of “every day.” The researchers found that the “toughest workouts every week” ad was more motivating. Too many consumers felt they could not work out every day. “If something does not seem feasible to individuals,” Ratner said, “they are just not going to be interested.”

Another key characteristic of memorable, actionable messages, Ratner explained, is that the action is easy to visualize. She mentioned a study in which the number of participants who actually took their vitamin (i.e., vitamin C) almost doubled when they received a message indicating when they were to take it (i.e., in the morning) instead of a message that lacked what social psychologists call an “implementation intention” (Sheeran and Orbell, 1999; see also Gallo and Gollwitzer, 2007).

Memorable, actionable messages also have embedded triggers, Ratner noted. Again, she said, the plate in plate-based messages serves as a trigger. When consumers see a plate, it reminds them to think about the guideline. Ratner described a study in which one group of students at Stanford University was shown the message, “Live the healthy way. Eat five fruits and vegetables every day.” Another group was shown the message, “Each and every dining hall tray needs five fruits and vegetables a day.” The researchers found that the first message had no impact on fruit and vegetable consumption, whereas the second significantly increased fruit and vegetable consumption, but only in the dining halls where students ate off trays. The trays needed to be present to remind them of the message, Ratner explained.

Concluding Thoughts

Ratner concluded her presentation by encouraging experts who want to send a message to think about whether their message meets the two criteria of memorability and actionability. She emphasized further the importance of testing messages. “Do not just rely on your own intuition,” she advised. She suggested that those wishing to communicate a guideline test it on their target audience and see whether people can recall it soon afterward, as well as after a delay, and whether the guideline is easy to use.

MARKETING TO EXPAND THE PRACTICE OF BEHAVIORS ASSOCIATED WITH FOOD LITERACY2

Trained as a clinical psychologist, Lefebvre began thinking about how to change the behavior of populations, as opposed to individuals, when he was a postdoctoral fellow and was taking his first public health course (in nutrition epidemiology). Thinking about populations led him to think about marketing, which in turn led him to co-create what is now known as “social marketing.”

Too often, in Lefebvre’s opinion, inadequate attention is paid to what sociologists and others call the “the micro-macro problem,” that is, the notion that changing the behavior of every individual, one by one, will

______________

2 This section summarizes information presented by Dr. Lefebvre.

eventually result in 100 percent of the population doing the “right” thing. “That is absolutely wrong,” he said. Changes occur at multiple levels, and the properties that emerge are not simply the accumulated actions of individuals. Applying the micro-macro problem to food literacy, Lefebvre cautioned against thinking only about how to change the behavior of individuals. He said, “Social change programs need to consider more than one scale of reality at a time.”

Lefebvre explained how diffusion-of-innovation theory is a helpful model for thinking about behaviors associated with food literacy. The theory categorizes the population into five groups: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards (Rogers, 2003). Any behavior usually follows a normal distribution, Lefebvre explained, with a few being innovators, slightly more being early adopters, about one-third of the population being early majority, another one-third being late majority, and the remainder being laggards (Rogers, 2003). With respect to food literacy behaviors, he said, the goal is to get the percentage of people who are engaging in healthy food behaviors as close to 100 percent of the population as possible.

Lefebvre emphasized the importance of keeping in mind the unique characteristics of each of these segments of the population when thinking about the people being served by programs designed to improve food literacy. What changes the behavior of an early adopter, for example, is not the same as what changes the behavior of an early majority individual. Innovators are venturesome, Lefebvre explained. They are already exploring ways to be more food literate and to eat more healthfully. “Innovators you never need to worry about,” Lefebvre said. Early adopters are respected and have the resources and risk tolerance to try new things, he noted. They also are well connected socially and locally. The early majority are deliberate. They are very engaged in their peer networks. They rely on personal familiarity before adoption—they have to see it to believe it. Most important, Lefebvre said, they ask the question, “How does this help me?” The late majority are usually quite skeptical of new things, he noted. And the laggards are traditionalists. Lefebvre remarked that he was focusing on early adopters and the early majority because the relationship between these two groups is a problem most people engaged in population behavior change efforts fail to understand.

All individuals ask themselves five questions when they receive messages about food literacy and nutrition behaviors, Lefebvre explained. First, how is this better than what I currently do? Too often, Lefebvre said, people sending messages forget that members of their target audience are already doing certain things with respect to food and are usually pretty comfortable, if not happy, with doing them. Therefore, he argued, communicators and marketers need to ask themselves how what they are offering is better

than what people are already doing. Second, how is this relevant to the way I go about my everyday life? Third, is it simple enough for me to do? Fourth, can I try it first? And finally, can I watch others and see what happens to them when they do it? While these questions seem simple, Lefebvre said, he questioned how many interventions actually answer them.

The differences between early adopters and the early majority and the “innovation chasm” created by those differences are what drive large-scale campaigns, Lefebvre observed (see Figure 3-1). Using adoption of a new technology, as opposed to a food behavior, as an example, he explained that with most technology innovations, when about 18 to 25 percent of the population is using the technology, one of two things happens: either people stop using the technology and it disappears, or the technology catches fire and takes off. When a technology disappears, he continued, the diffusion curve turns into what is known as a “fad curve”; when it takes off, the curve becomes what is known as an “accelerating curve.” Bridging the chasm between early adopters and the early majority is what makes the dif-

FIGURE 3-1 The “innovation chasm” between early adopters and the early majority in the adoption of a new technology.

SOURCE: Presented by Craig Lefebvre on September 4, 2015; adapted from Moore, 2014. Copyright (c) 1991 by Geoffrey A. Moore. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

ference, he said. He underscored the unique characteristics of early adopters versus the early majority. The early majority is watching the early adopters to see whether the innovation, or the behavior in the case of food literacy, is worth trying and whether the early adopters are having success with it.

“It is not until we begin segmenting and thinking about people in terms of the characteristics people have to acquire new behaviors that we are going to be successful at big population change with respect to food literacy,” Lefebvre argued. This means, in his opinion that experts in the field of food literacy need to change the way they think. “If there is a takeaway from this presentation,” he said, “it is that if we want to improve food literacy and we want to reduce obesity, we have to change ourselves first.”

Changing the Way Researchers Think

Instead of bringing people into experiments, as public health researchers tend to do, most consumer researchers go out into the field and watch people, Lefebvre noted. He remarked that one of his favorite market research sayings is, “If you want to learn how a lion hunts, you have to go to the jungle, not to the zoo.” But even market researchers out in the field usually have certain things in mind, he observed. He showed a cartoon image of a man inside a kitchen washing dishes, trying to scrape food off a plate, and a consumer researcher outside the window watching. The man has a thought bubble filled with the image of a drill and chisel, while the consumer researcher has a thought bubble filled with the image of a bottle of liquid detergent. In this situation, Lefebvre explained, the consumer researcher is trying to come up with ways to sell the bottle of soap to someone who is obviously having a problem cleaning his plate. But the man does not want a stronger dishwashing solution; he wants a power tool or chisel. His problem is not that he wants cleaner dishes; his problem is that he wants to get the food off his plate. This difference between what the consumer and the researcher are thinking is important, Lefebvre said. If the problem people are trying to solve with food literacy cannot be identified, he argued, efforts to sell different kinds of behaviors around nutrition will not be successful.

Motivation is key, Lefebvre stated. Consumers’ motivations need to be understood, he said, as do the values that current and proposed behaviors might create for them. Based on his experience as a psychotherapist, he believes it is rare to be able to change people’s motivations as much as one would like. Perhaps in individual counseling, over the course of months or years, it is possible, he said. But otherwise, he asserted, for the most part one cannot change motivations; rather, one must figure out how to tap into existing motivations. He speculated that most workshop participants who had visited the MyPyramid website had not done so to learn how to

eat more healthfully. “Most of you went there because you were curious,” he said, and that is a different motivation. He stressed the importance of understanding the motivations of people out in “the jungle.” Once those motivations are understood, he suggested, researchers need to generate possible solutions to help people meet their needs, solve their problems, or achieve their dreams.

Another problem with much research, Lefebvre continued, is what is called “the depth deficit.” Many consumer researchers have found that people in focus groups or in experiments lie about their thoughts and experiences—not deliberately, but because they cannot explain why they do what they do. This phenomenon, explained Lefebvre, creates a gap between the way people experience and think about the world and the methods used by most researchers to collect information.

Yet another problem with focus groups and interviews, according to Lefebvre, is that researchers with a priori hypotheses are essentially “leading the witness.” He referred to Sonya Grier’s discussion of the importance of understanding the emotional context of food well-being (see Chapter 1) and stressed that researchers need to assess the emotional, as well as rational or functional, value that people place on specific products, services, and behaviors. Yet in very few focus groups, he observed, do people cry or laugh; most such groups are remarkably flat in tenor, he suggested.

Lefebvre noted that consumer researchers also have identified what is known as the “say-mean gap.” He urged researchers to use methods that allow people to tap into their unconscious processes—“that second level” or automatic level of thinking that guides much of what people do. Additionally, he called for a greater understanding of shared mental models and the context in which people think about food. What are the stories? What are the archetypes? He told the workshop audience how much of his current work involves sending people out with cameras to capture everyday life. Then in focus group discussions, they discuss why they took the pictures they took, what the pictures mean, why certain things are in the pictures, what was not in the frame, and so on. Lefebvre suggested that this is a way to get people to talk about things they normally would not verbalize when asked a question about their motivation (e.g., why they eat the foods they do).

With respect to helping to solve the problem of food literacy, Lefebvre pointed out that the key for consumer researchers is not to confirm hypotheses; rather, the key is to generate insights into consumers and to discover things about them that were not known before. He tells his students that every research project should rock their world and that in the end, they should be thinking about the problem very differently from when they first considered it. The same is true if one wants to change people’s behaviors with respect to food, he suggested. The first thing one must be able to do is

think as they do. “If you want to catch a fish, first learn how to think like a fish,” Lefebvre said.

Understanding the Consumer’s Point of View

Lefebvre suggested that one way to gain insight into the consumer’s point of view is by focusing on positive deviants, that is, the people who are already doing things the way one would like the rest of the population to be doing them. Some people might call these positive deviants the innovators, he noted. They are the people who have figured out for themselves how to make healthy eating part of their normal daily routine. Too often, Lefebvre said, researchers conduct population surveys and try to understand the distribution of a behavior by focusing on individuals who fall within the 95th percentile confidence interval; in other words, they focus on the middle. But the middle provides no insight into how to change behavior, in his opinion; it only helps describe what the problem is. Someone who has not eaten a fruit or vegetable for the past 10 years, he argued, can reveal much more about why people do not eat fruits and vegetables than can someone in the 50th percentile. The same is true of someone who has been eating fruits and vegetables since early childhood, he suggested. Yet these are usually the groups excluded from research. As long as the focus remains on the middle of the distribution, Lefebvre emphasized, researchers are not going to gain insight into how to change behaviors. Only when they start talking to positive deviants, he believes, will they be able to start pushing the diffusion curve.

Once researchers begin to understand what positive deviants are doing “right,” they need to think about not individual but social network interventions, Lefebvre continued. He described obesity as a social disease, with people who are obese clustering together. “Forget the celebrities,” he said. “Let’s talk about groups. . . . People learn by watching other people, not by listening to messages.” As an example of a social network intervention, he cited Koehly and Loscalzo’s (2009) use of peer networks and family support mechanisms to address adolescent obesity.

To illustrate what can be learned from a positive deviant, Lefebvre pointed to Brett Arends, a columnist for The Wall Street Journal, who lived for 6 weeks as though he was participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and had only $4.30 per day to spend on food. “It seemed impossible until I worked out the trick,” Arends wrote in one of his columns. “Then it became surprisingly manageable.” Lefebvre explained how Arends did not eat out, did not eat packaged or processed foods, did not eat energy bars, avoided cheap carbohydrates (e.g., white bread and noodles), and did not purchase coffee. He ate large amounts of peanuts and peanut butter (which cost around $2.50 per pound), eggs (20

cents each), legumes, a cup of milk per day, healthy carbohydrates (e.g., oatmeal, whole-wheat bread that he made at home), bananas, frozen mixed vegetables, and a daily multivitamin. According to Lefebvre, Arends actually gained weight over the course of the 6 weeks. One of Arends’s favorite places to shop for food ended up being the food aisles of drugstores, where what was on sale was on the menu that night. Arends spoke with a nutritionist, but otherwise, no communication campaign helped him do this. The take-home message is that Arends learned a great deal, and others can do so as well, Lefebvre said. Arends wrote, “My experience has changed how I eat. I am amazed at how cheaply one can eat well—and mortified at how much I have spent needlessly over the years.”

Concluding Thoughts

In addition to collecting the kind of information he discussed and putting it together as social marketers do, Lefebvre emphasized the importance of understanding the competition—not just the food companies, but those who send all the other nutrition messages consumers receive. He mentioned a recent Health Affairs study that found that people had not been shopping at a new supermarket built in a low-income, “food desert” neighborhood, leading the researchers to conclude that complementary initiatives were needed to encourage adoption of the new store (Cummins et al., 2014). Lefebvre said, “In my world, we call that marketing.” Other researchers have concluded likewise (Wakefield et al., 2010). In closing, Lefebvre quoted Green and colleagues (2009): “We conclude from this review that applied health sciences research would have a much enhanced probability of influencing policy, professional practice, and public responses if it turned the question around from how we can make practice more science based to how can we make science more practice-based?”

THE SOCIAL NORMS APPROACH: CHANGING BEHAVIOR THROUGH A PARADIGM SHIFT3

Successful interventions express empathy, offer no argumentation, support self-efficacy, and recognize the discrepancy between individuals’ behavior and the normative behavior in the population, Bauerle began. She focused on the last characteristic—the discrepancy, or perception gap, between what people are doing and what they think their peers are doing. She pointed to alcohol use among college students as an example. A 2014 National College Health Assessment (NCHA) Web survey (N = 79,266) showed that individual college students had consumed, on average, 3.39 al-

______________

3 This section summarizes information presented by Dr. Bauerle.

coholic drinks the last time they “partied” or socialized, compared with the 5.57 drinks they thought a typical student at their school had consumed. Similar gaps in perception have been reported in nutrition and with many other public health applications, according to Bauerle.

Bauerle explained how shrinking the gap between perception and reality can be achieved by focusing on the norm. Elevator behavior is a good example of a social norm, she said. When one gets to an elevator, one presses a button, the door opens, one waits for others to exit, one enters, and one again pushes a button. Nobody learns elevator behavior by being taught, Bauerle said. The behavior is an unspoken social rule that people understand by watching, listening, and talking with others. Bauerle suggested that an amusing social experiment is to enter an elevator and, instead of pressing a button, just turn one’s back to the door and stand there. “You will watch everybody get off on the next floor,” she said. “I promise you.”

“We are social beings,” Bauerle continued. She mentioned a landmark study by Solomon Asch, who presented participants with “Exhibit 1,” a drawing of a single line, and “Exhibit 2,” a drawing of three lines, including the line in Exhibit 1. He asked the participants to tell him which of the three lines in Exhibit 2 matched the line in Exhibit 1. This is a fairly simple task, Bauerle observed. But Asch “planted” people in the room to give the wrong answer and then watched what other people would do upon hearing the “plants” give their wrong answers. Often, they would respond with the same wrong answer.

Perceptions of norms thus are important, Bauerle said. Sometimes they can be right, but sometimes they can be wrong, and such misperceptions can be quite damaging. Bauerle suggested that misperceptions occur because whatever stands out is what people focus on. She observed that this reaction is “deep in our biology” because when humans were hunter-gatherers, they evolved to notice something “amiss,” such as when a predator was present. She played a 90-second “selective attention test” video that showed several people wearing either white or black, moving around and passing basketballs to each other (www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJG698U2Mvo [accessed March 17, 2016]). She asked the workshop participants to keep track of how many times the players dressed in white passed a basketball. After the video ended, the participants called out numbers. The correct number was 15. She asked whether anyone had seen anything else—specifically, whether they had seen, in the middle of the video, the person dressed in a gorilla costume walking into and through the group of people passing basketballs. The expectation was that viewers would be so focused on the people in white passing the basketballs that they would not see the gorilla. This exercise, Bauerle explained, demonstrates that whatever one focuses on expands. If what one is focusing on is a perception, regardless of whether it is a correct perception or a misperception, that perception expands.

A social norms approach to intervention involves focusing on people who are doing the things one wants people to be doing, Bauerle explained, and then expanding that perception. The approach involves collecting information to identify the norm, and then holding the norm up like a mirror and giving people the space to make their own choices. It represents a paradigm shift—a new way to bring about behavior change. Instead of assuming, lecturing, or “terrorizing,” Bauerle said, a social norms campaign persuades people by telling them, “This is what we are actually doing. Come along with us.”

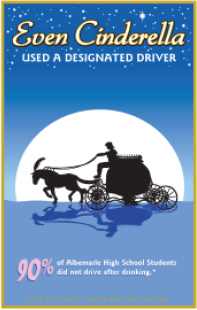

As an example of a social norms campaign, Bauerle described a high school’s campaign to prevent driving after drinking on prom night. Instead of the image of a crashed car, students chose the image of a horse-drawn carriage and text that read, “Even Cinderella used a designated driver” (see Figure 3-2). Bauerle explained that not only did the campaign highlight positive behavior, but it also was based on input from all students, including both the high-risk drinkers and those who drank responsibly. She agreed with Lefebvre that, in her words, “you need everybody in your sandbox.”

Bauerle showed another example of a drinking and driving behavioral norms campaign poster, this one for the state of Montana. It shows a group of young adults playing on an inner tube in the snow, all of them smiling

FIGURE 3-2 Poster designed by high school students as part of a social norms campaign developed in consultation with Jennifer Bauerle to prevent drinking and driving on prom night.

SOURCE: Presented by Jennifer Bauerle on September 4, 2015.

and looking as though they are having fun, with text that reads, “MOST Montana young adults (4 out of 5) don’t drink and drive.” Bauerle did not elaborate, but listed several studies on the use of a social norms approach in the area of food literacy (Burger et al., 2010; Fellner et al., 2009; Goldstein et al., 2008; Higgs, 2013; Mollena et al., 2013).

Bauerle noted that a social norms campaign can be run even when the behavior to be expanded is not the majority behavior, but instead of expanding a social norm, the campaign focuses on and expands an attitudinal norm. The example Bauerle showed was a poster with the image of ice hockey players and text that read, “74% of HWS Student-Athletes believe tobacco use is never a good thing to do.” She noted that studies have shown that social norms campaigns based on attitudinal norms do work. In one study, her research team showed that first-year college students exposed to an attitudinal norms campaign that corrected misperceptions of campus drinking had 24 percent lower odds of having a blood alcohol concentration greater than or equal to 0.08 (p = 0.024) and 22 percent lower odds of suffering at least 2 of 10 possible negative consequences (e.g., injury, fighting, forced sex, unprotected sex) (p = 0.002).

In conclusion, Bauerle emphasized that the most important feature of the social norms approach is that it focuses on being positive, inclusive, and empowering. It is a way to meet an audience where they are and to have them “come along.” Additionally, Bauerle emphasized the importance of experts communicating with each other and learning from each other’s failures. “It’s important to know what does not work so that we don’t redo it,” she said. She also emphasized the importance of making sure that “the message you are giving is the message that they are getting.”

VALUES AND VITTLES: A COMMERCIAL MARKETING PRACTICES CASE HISTORY4

Nagle began by declaring that he “detests” the concept of food literacy because it is premised on the “wrong-headed” notion that a well-informed citizen will do the right thing (despite centuries of evidence to the contrary). That said, people do behave in reasonably understandable ways, in his opinion. He mentioned Dan Ariely’s book Predictably Irrational, which makes the point that people operate on multiple levels that are not about rationality or information (Ariely, 2008). “That is probably at the heart of what I want to talk about today,” he said. He would be talking about values-based messaging, he told the audience, focusing on the case history of a canned food campaign conducted by his firm, Statler Nagle, LLC, which designs marketing programs mainly for industry groups. For

______________

4 This section summarizes information presented by Mr. Nagle.

him, Sonya Grier’s food well-being construct (described in Chapter 1) is a “brilliant” way to encapsulate much of what he believes is important for effective marketing.

Nagle explained that while Consumer Reports is a great magazine for helping consumers decide what kind of toaster to buy, with its descriptions of all the attributes and costs of different brands, it is not the way humans make decisions about health and other important matters. Taking the example of buying a house, a great deal of rational thinking goes into the process, but, he suggested, none of it has any relevance. “You are looking at houses,” he said. “You are walking through neighborhoods. You walk in a house and, in my case, your wife says within 11 seconds, ‘We will live here.’” His wife, he said, may not have been making a fact-based decision but is a smart woman who was making the right choice. When she made that decision, she was operating at a subconscious level of values and emotion in which facts may play a role, but are not determinative. Nagle referred to another book, David Brooks’s The Social Animal, which delves into the subconscious decision-making process and the science behind it (Brooks, 2011). Facts may persuade, Nagle explained, but it is emotions and values that motivate decisions and behavior, and they are a key entry point into effective messaging.

“Cans Get You Cooking” was a campaign that Statler Nagle ran for manufacturers of metal cans for food. Can sales had been in decline for some time, and their continued decline was anticipated, Nagle recalled. Consumer research had revealed that consumers perceived canned foods as being full of preservatives, dull and tasteless, unhealthy, and backward. Consumers also showed high levels of cynicism regarding food labels and ingredient statements indicating that canned foods were preservative-free. An interesting finding from focus group research, Nagle said, was the way consumers responded to being told that home canning was what their grandmothers used to do. That message in particular helped change negative perceptions of canned foods.

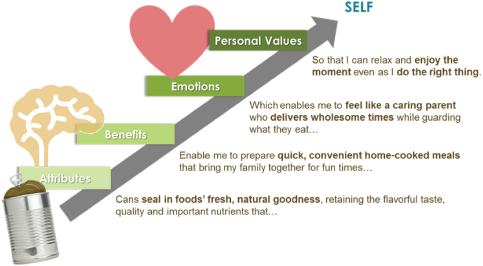

Nagle described the “very powerful force” revealed by the values study of canned foods that he and his team conducted. Values studies link the attributes and benefits of, in this case, canned foods, to the target audience’s emotions and personal values (see Figure 3-3). The target audience in this case was primarily mothers. According to Nagle, the marketers concluded that, from a consumer perspective, the links among the attributes, benefits, emotions, and personal values around canned foods could be described as follows: “Cans seal in foods’ fresh, natural goodness, retaining the flavorful taste, quality and important nutrients [i.e., the attributes] that enable me to prepare quick, convenient home cooked meals that bring my family together for fun times [i.e., benefits], which enables me to feel like a caring parent who delivers wholesome times while guarding what they eat [emo-

FIGURE 3-3 Results of a values study that connected the attributes and benefits of canned foods to the target audience’s emotions and values.

SOURCE: Presented by Tom Nagle on September 4, 2015. Reprinted with permission.

tions] so that I can relax and enjoy the moment even as I do the right thing [personal values].”

The mistake many marketers make, Nagle said, is that they design their campaigns based only on emotions. While he agrees that emotions are important, all four rungs of the “ladder” illustrated in Figure 3-3 need to be communicated, although not necessarily explicitly. They can be communicated in context, such as in pictures. The “magic,” Nagle explained, comes from linking all these different rungs of the ladder so consumers can make the full journey up the ladder, successfully connecting the different layers of benefits to the relevant values. Importantly, he said, “The journey is not to some place they have not been. The journey is to get them to where they already are.” He continued, “We are not changing people’s values. We are not changing people’s emotions. We are putting what we want in terms of behavior change in the context of the values and the emotions they already have.”

The essence of the “Cans Get You Cooking” campaign was helping women be successful mothers and derive the emotional and value benefits that are inherently important to them. In all the consumer research Nagle and others have done, parents have reported feeling better when they prepare home-cooked meals for their children. But preparing home-cooked meals for children 7 days per week is difficult, Nagle pointed out, and using

canned foods makes it easier. Canned foods equal less worry, less guilt, and more enjoyable family time, and give people the ultimate benefit of doing the right thing and being successful parents, he stated.

The initial primary messages of the canned soup campaign were that (1) cans seal in freshness, flavor, nutrition, confidence, and approval; and (2) cans are an ideal tool for creating more—and more successful—meal occasions. These messages were disseminated through multiple avenues, including paid, earned, and owned media; social media; and outreach to nutritionists and grocery store chains. Nagle noted that when his team reached out to registered dieticians, the response was very positive with respect to both the nutritional and “easy solution” aspects of canned foods that were being promoted. On social media, he reported, the increased volume of positive messaging around canned foods was reflected in a dramatic tripling of total mentions and doubling of positive mentions of canned foods.

To determine whether the campaign changed behavior—that is, whether people actually were eating more canned foods—Nagle and his team conducted a tracking survey. They asked consumers not only whether they had heard the message about canned foods, but also whether they had eaten more canned food in the past 6 months. Indeed, the team found what Nagle described as a “marvelous” positive correlation between exposure to outlets for the message and greater reported use of canned foods. Additionally, they found that use of canned foods increased following initiation of the campaign.

Nagle clarified that although social media have made it less expensive to achieve certain communication goals, use of social media is not a strategy. “It is just a tactic,” he said. Still, the results of the survey question related to sharing opinions about canned foods, either online or in person, were interesting, in his opinion. Twenty percent of respondents reported that they had shared an opinion about canned foods in the past 6 months, and among those who had shared, most had positive opinions (81 percent) rather than neutral (9 percent) or negative (10 percent) opinions.

Concluding Thoughts

To conclude his remarks, Nagle discussed what is known in marketing as “the Got Milk? fallacy.” People have the idea that the perfect message, well crafted and well delivered, will change the world. That is wrong, Nagle asserted. He believes the message alone is not enough. Rather, it must be sent all the way through the value chain, with retailers and other value chain participants being engaged in the campaign. For its canned food campaign, Statler Nagle worked not just with the makers of metal cans but also with retailers to change their in-store messaging. Instead of the typical “10 for $10,” Statler Nagle told retailers they needed to send a different canned

food message tied to the benefits ladder, and to deliver that message in as many places as possible—in their aisles, on their shelves, in their circulars, and in their frequent shopper communications and emails. In Nagle’s opinion, this type of full marketing architecture is entirely applicable to public health. The value chain and players may be different, he said, “but at the end of the day, it cannot just be messages.”

USING PARTICIPATORY DESIGN TO IMPROVE LARGE-SCALE FOOD LITERACY5

Mauritania: A Case Study in Participatory Design

Neuhauser listed three ways to advance food literacy: (1) set a big goal; (2) use participatory design; and (3) focus on parents and young children. The emphasis of her presentation was on participatory design, specifically a type of participatory design known as design thinking. Her own interest in participatory design emerged during what she described as a transformative period in her life. When she was awarded her doctorate in nutrition, she was highly enthusiastic about being a nutrition educator and “changing the world.” But she quickly realized that few clients wanted her science-based advice. Her colleagues would tell her just to talk louder, that it was “our job as experts to tell people the best scientific knowledge” and “their job to follow through with it.” Neuhauser began to wonder whether people were unable to connect with that scientific knowledge not because the experts were not persistent enough, but because people live such complicated lives. “We have messages to send, but people have lives to live, and we don’t often bridge the two,” she said.

Neuhauser became so frustrated with not being able to connect with the public that she quit her new career as a nutritionist within 6 months of starting it. She joined the U.S. Department of State (in the area of foreign aid) instead and went to Mauritania in West Africa. At the time, Mauritania had been trying to establish a national vaccination program. Tens of thousands of people had been dying every year from vaccine-preventable diseases, despite the efforts of experts from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization to promote vaccination. Even though Neuhauser and her new colleagues knew what a good vaccination program was supposed to look like, they did not how to develop one that would fit within the complex reality of the lives of people living in Mauritania. Again, she said, she was facing another failed career within 6 months of starting.

In desperation, Neuhauser decided to do something that changed her

______________

5 This section summarizes information presented by Dr. Neuhauser.

life. She decided to “stop being an expert” and go out and rely on the people to say, “Here is how this program could be made to work.” She and her colleagues started traveling around the country and soliciting proposed solutions from people.

Place by place, people began to solve seemingly intractable problems, Neuhauser reported. One important technical problem remained: how to develop a way to keep vaccines cool enough in the Sahara Desert. It was the camel drivers who ended up having the answer (using a network of special veterinary refrigerators), she told the workshop audience—but no one had ever asked them. So after 20 years of failure, diverse population groups redesigned the program so that it successfully covered the vast majority of the country in just 2 years. At that point, Neuhauser said, she decided to devote the rest of her career to learning about and applying participatory design. Today, user-centered design is the focus of the Health Research for Action center at the University of California, Berkeley (where Neuhauser serves as co-principal investigator).

Neuhauser explained that participatory design, in its simplest terms, is an active process in which users transform current conditions into an improved future (Simon, 1996). The emphasis, she said, is on “users,” “transform,” and “future.” Researchers do not always focus on users or the future, in her opinion, and they do not always set the bar high enough to pursue transformation. She explained that participatory design is rooted in the design sciences, a branch of scientific inquiry that emerged in the 1960s within the purview of architects, engineers, and people in other sociotechnical fields. Its epistemological foundation is quite different from what underlies most of the work done by researchers trained in the social and health sciences, she noted. She observed that participatory design is not the study of “what is,” which is what most researchers examine most of the time. “That is how we are trained,” she said. Rather, it is the study of “what might be”—of how to be in the future, how to create that future, and how to evaluate that future.

Typically, Neuhauser continued, researchers define problems based on the literature and then devise an intervention they think relates to those problems. They obtain funding for the proposed intervention, implement it, and finally evaluate it. These interventions are typically effective only half of the time, according to Neuhauser. “This is a very low bar in terms of success,” she opined. The participatory design process is very different (Roschuni, 2012), she noted. It involves two interlocking, simultaneous and ongoing activities: constantly defining and looking for problems, and constantly generating and testing solutions. Neuhauser described the process as highly iterative and user-centered. It is users who are defining the problems, generating the solutions, and constantly redoing both over time.

Design Thinking

Although there are many types of participatory design, one that Neuhauser believes is especially powerful and that has been “taking the world by storm” is design thinking. Developed by David Kelley, who founded the Stanford Design School, or d.school, as well as the spin-off company IDEO, design thinking was first used by engineers, architects, and computer scientists, although businesses have rapidly adopted it. Neuhauser mentioned that Steve Jobs was one of Kelley’s first clients and that the two worked together for many years, using design thinking processes. That collaboration is credited with helping to develop what has become one of the most successful companies in the world, she noted. Today, she observed, design thinking is slowly making its way into the research community. All Stanford University students are required to take a course in design thinking, for example, and she requires all of her students to learn it.

Neuhauser characterized design thinking as a fearless, radical collaboration to create a vision and make it happen. It is a “no holds barred” type of process, she said, involving a number of steps that are taken more or less simultaneously. As defined by the Stanford d.school, the first step is to have empathy, which she described as “actually getting into someone’s shoes.” It means really observing, as an anthropologist does, and understanding what someone is feeling about a particular problem or solution. If one cannot do that, Neuhauser said, one “cannot proceed beyond that first stage.” While this is not the bar that researchers typically set, she noted, it is the bar that design thinkers set. “You have to get to the emotional level,” she emphasized. The second step is to define a big vision based on the kinds of issues being raised by users. The third step is to ideate, that is, generate as many ideas as possible in a fearless way, regardless of how wild or weird they may seem. Neuhauser observed that wild and weird ideas often emerge during this part of the process, but it is such ideas that in the end are most transformative. The next steps are to prototype, then test, and continue to do that until the users are satisfied.

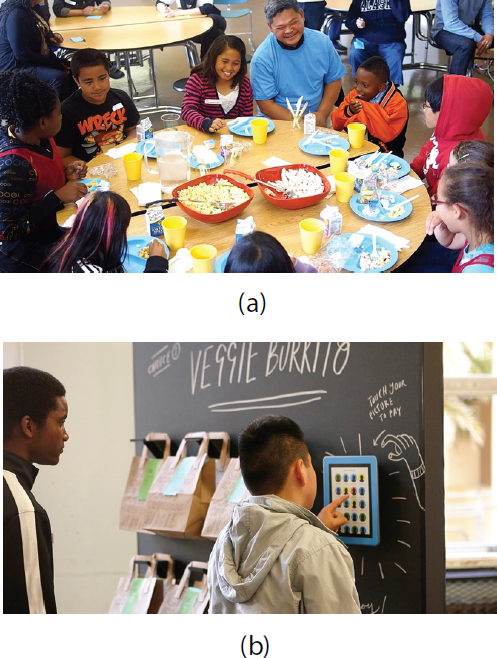

A Cafeteria for Me

Neuhauser described an example of the use of design thinking in the food literacy world: “A Cafeteria for Me” (www.IDEO.com), a school lunch project developed when the San Francisco Unified School District approached IDEO with what it described as a “real problem.” Participation in the district’s school lunch program was poor, she noted, with both students and teachers being dissatisfied, nobody learning anything about food and nutrition, and the school district losing millions of dollars per year. IDEO accepted the challenge and set a vision for a “student-centered, financially

stable system that engages kids in eating good food.” This is an example of a big vision, Neuhauser remarked.

Neuhauser reported that IDEO engaged approximately 1,400 people in its design thinking process, including students, teachers, administrators, local farmers, chefs, entrepreneurs, parents, politicians, and media professionals. All of these people were involved as users in what she described as a “cauldron” of ideas. At the time of the workshop, they had been working together for about 2 years. Neuhauser said she was “absolutely blown away” by some of what was discovered in those first 2 years. For example, as part of their prototyping, the team designed model lunchrooms so that users could have an actual feeling for such a place. The models made what was being proposed seem real, Neuhauser noted, rather than something abstract that existed only on paper. One of the solutions for elementary school lunchrooms was to create family-like situations that allowed for discussion. So instead of the “free-for-all” that existed before, students in some schools now sit down at tables and are served courses (see Figure 3-4a). Additionally, as a result of students saying they did not like waiting in lines because it took up much of their lunch time, some schools now have a system in place whereby the students can pre-order their food (on tablet computers) so that it is ready for pickup at lunchtime (see Figure 3-4b). Additionally, the students designed a mobile cart so their lunches could be delivered to the playground, greatly increasing participation in the lunch program in just a few weeks, according to Neuhauser.

Neuhauser explained that before the school district engaged IDEO, the school lunch program was a failing system, one that people had been trying unsuccessfully for years to improve. But by applying a little design thinking, removing the limits on people’s dreaming, and having them live in the future, “bingo,” she said, “they did it.”

Neuhauser provided workshop participants with several references on participatory design and design science (Neuhauser and Kreps, 2014; Neuhauser et al., 2007, 2009, 2013a,b; Simon, 1996). Additionally, for more information on the “A Cafeteria for Me” program, she referred the participants to https://www.ideo.com/stories/a-cafeteria-designed-for-me (accessed March 17, 2016).

Parenting Education

Neuhauser briefly addressed the third way to advance food literacy mentioned at the beginning of her talk—focusing on parents and young children. “Unless we start really early with parents and young children, we are never going to change anything,” she said. She noted that studies show that because it is very difficult to change behaviors among adults, even teenagers, the best “return on investment” is with young children (Heckman

FIGURE 3-4 Changes in a school lunch program that resulted from a design thinking study. (a) Family-style meals, with food being served in courses. (b) The ability for students to pre-order their food, eliminating their wait time.

SOURCE: Presented by Linda Neuhauser on September 4, 2015; figures courtesy of IDEO (www.IDEO.com).

and Masterov, 2004). She mentioned an intervention study with which she was involved that had a goal of reaching 500,000 new Californian parents every year with an information kit (on parenting) and then expanding the program to other states (Neuhauser, 2010; Neuhauser et al., 2007). She and her collaborators used what she called a “very deep participatory design” process, one that involved constantly making changes based on input from thousands of parents. The program achieved an 87 percent usage rate in California, with significant improvements in parents’ knowledge and behavior (Neuhauser et al., 2007). In addition to being expanded to Arizona, where it has also been highly successful, the program was being expanded to other states and had been adapted for use in Australia.

Neuhauser mentioned another ongoing parenting education initiative with the ambitious goal of reaching 10 million parents in the United States with children aged 0 to 5 years. Again, she and her collaborators are using participatory design. They are learning that parents not only want more information about early brain development, prenatal care, nutrition, and the like, but also want that information communicated via short videos on the Internet, on phone apps, on YouTube, and through other “new media” avenues. In addition to talking with parents, providers, and other users and stakeholders, Neuhauser’s team is working with partners in Hollywood. She described the collaboration as a “big tent” and invited any interested people to “come and design with us.” The expected launch date is late 2016.

Following Neuhauser’s presentation, she and other Session 3 speakers were invited to participate in a panel discussion. Audience members asked a range of questions about communication tools and strategies for promoting food literacy. This section summarizes that discussion.

Studying Population-Level Interventions

Lefebvre had emphasized during his presentation the importance of working with populations as well as with individuals. Johnson-Askew asked him how researchers would design a study of a population-level intervention, given that they tend to be reductionist in their thinking. Would it require a collaborative effort, or could a single study examine both individual- and population-level phenomena? Lefebvre suggested designing a study that would randomize by communities or by media markets, assuming an unlimited budget. In his opinion, there has been very little research demonstrating that segmentation works or that it is critical. He suggested running a classic media campaign in, say, five randomized communities, and then segmenting another five randomized communities. In the

latter communities, the focus in the early months of the campaign would be on the innovators and early adopters and then, about 8 months into the campaign, it would shift to the early and late majorities, with the message changing accordingly. As outcomes, Lefebvre suggested that the study could examine not only whether people being exposed to the two different campaigns received and heard messages differently, but also whether they were behaving differently.

Shifting the Social Norm of Obesity

Johnson-Askew asked Bauerle how she would propose shifting the social norm of obesity. In Johnson-Askew’s opinion, as obesity becomes prevalent, people also are becoming accustomed to seeing fat people. Bauerle explained that if the majority of the population is doing something one does not want them to be doing, one can still conduct a social norms campaign, but with the focus on an attitudinal norm, not the behavioral norm. As she had noted, most people have healthy attitudes. So one can focus on and expand those healthy attitudes, she suggested, which will push against the behavioral norm (in this case, obesity) to get that behavioral norm moving. At least that is what she would recommend as a first step. She commented on the “complicated” nature of the “big answer.”

Upon hearing Bauerle express how complicated it will be to shift norms around obesity, Johnson-Askew reminded the workshop audience that too often, researchers look for a quick answer when the time horizon for solving many such problems is much longer than that for research study funding. Baurle responded that she and her colleagues at the University of Virginia like to tell people, with respect to their social norms research results, “We are a 10-year overnight success.”

Self-Efficacy and Success

In addition to its impact on actionability, Johnson-Askew asked Ratner whether self-efficacy, or an individual’s belief that he or she can do a thing, might also have some impact on memorability. Ratner was unaware of any research on the effect of self-efficacy on memorability, but it made sense to her that this would be the case. She pointed out, however, that some work has been done on what is known as the self-referencing effect, showing that thinking about how something applies to oneself makes it more memorable.

Johnson-Askew opined that feeling like a success, the importance of which Nagle had emphasized during his presentation, is a little different from feeling as though “I can do it.” If the goal of a marketing campaign is to make people feel that they are a success—as was the case with the canned food campaign, which aimed to make mothers feel that they were

doing a good job preparing foods for their families—she asked Nagle what public health experts should be leveraging with their messaging that they are not currently using.

Nagle pointed out that values around success are deeply rooted culturally. The goal is not to change people’s values, he said. Rather, the goal is to connect the behavior to values “they come to the game with” so that individuals see the behavior as a pathway to actualizing their own values. Johnson-Askew suggested then that the goal in public health would be to connect the behavior to people’s willingness to be healthy. But experts in public health do not make that connection very often, she observed. Instead, they devise interventions that entail what they think people should do.

Lefebvre emphasized the importance of understanding not what public health experts’ aspirations are for people but what people’s aspirations are for themselves. In his opinion, people do not aspire to be healthy; people want to be healthy only so they can do all the other things that are important in their lives. He believes that only when public health experts step back and start asking how they can help people be successful in their lives, in whatever way people define success, will public health messages be successful. Asking how to help people live more fulfilling lives is very different from asking how to help them live healthier lives, he suggested. “I don’t buy into aspiring to have a healthier America,” he said.

Funding Participatory Design Research

The “A Cafeteria for Me” program described by Linda Neuhauser was “unbelievable,” in Johnson-Askew’s opinion. She asked Neuhauser about funding for participatory research, given the length of time it takes to build relationships and develop an understanding of a community’s needs. Neuhauser suggested reframing the question and observed that in fact, failure costs much more than success. “We spend billions failing,” she said. In her opinion, design thinking is helping to reframe the confidence funders have in where they put their money. She noted that funders are becoming confident that with design thinking, the outcomes will be transformative. And participatory design attracts many partners, she observed. The “tent” is big, she said, so funding is not as great a problem in her experience.

People Value the Present More Than the Future

A challenge for economists with respect to behavior change, Helen Jensen observed, is that people discount the future. This phenomenon is known as “present value bias.” Jensen cautioned that, when thinking about programs and the choices being offered, it is important to keep in mind that

people value the present more than they do the future. She asked the panelists how future benefits can be brought into present choice more effectively.

Neuhauser reiterated that most traditional research is situated in the present, with people thinking about the way things are now. She suggested that little can be gained by going into a school lunchroom and asking students whether they would like to eat a healthier lunch. But if one asks those students to design something to achieve their “dream lunch,” one gets them to live in the future. And when they live in the future, Neuhauser said, “they will design things that are extraordinary.” She noted that she had only touched the surface of the “A Cafeteria for Me” program and mentioned how the students in that program had also designed ways to work with their local communities to improve food security. They had come up with designs that would actually bring money back into the school. In Neuhauser’s opinion, design science provides good guidance for conducting research with a “future mindset.”

Taking a different perspective, Ratner agreed that most people are not good at valuing the future and suggested that successful interventions are therefore those that focus on present benefits. She suggested that a mobile technology-based social norms approach might be helpful. She imagined using mobile technology to give people feedback about what their neighbors are doing, or eating.

Lefebvre said he has wondered ever since mobile technologies emerged how they can be used to “make the future present.” However, “not everyone future discounts,” he observed. In his opinion, the real question is how to design interventions tailored specifically to those people who do future discount.

Promoting Fruits and Vegetables

Public health experts across the United States have been working for more than 30 years to promote fruits and vegetables, Vivica Kraak, workshop presenter, observed. In fact, she noted, international programs have been modeled on the U.S. “5 a day” program, which is now the “Fruits & Veggies—More Matters” initiative. She asked what can be done to make those messages more meaningful to people and inspire them to eat more fruits and vegetables.

Lefebvre expressed disappointment with how the “5 a day” campaign has evolved. He described what Israel has done with its version of a “5 a day” campaign and how that campaign has been successful. The campaign revolves around what he described as the “food heaven” culture of the birthday party. Through YouTube videos, other social marketing, and other means, the health ministry in Israel campaigned to turn birthday parties into healthy birthday parties, with fruits and vegetables always

present and with less alcohol. According to Lefebvre, the health ministry recently issued a 1-year report indicating that the campaign was probably the most successful it had ever conducted. It was successful, he explained, because of its combined participatory design and social norms approach. Parents and others were invited to help design the campaign and “dream” about their future. The campaign was designed to fit with people’s reality, Lefebvre said. “It was not just a bunch of experts sitting in a conference room saying, ‘Here is how a birthday party should look.’” Plus, Lefebvre continued, it was big. “If you want have a big effect,” he said, “then you have to have a big campaign.”

Educating the Next Generation of Food and Nutrition Communicators

An audience member commented on the new generation of health professionals, including dieticians, physicians, Ph.D.s, and nurses, who have grown up using social media but have not necessarily been trained in how to communicate with the general public or to the media. She wondered how health professionals can be educated in effective communication and how social media connectivity can be leveraged to get messages out.

Nagle observed that it is difficult to tell dieticians and others that they need to stop talking about the facts and start talking to people about “how to be successful in the context of their own personal values.” That takes training of a different sort than nutrition or medicine, he suggested. Bauerle said, “I think we need to step out of our own way because we are not always the best vehicle for the message.” She mentioned a heart health campaign that relied not on health professionals but on hairdressers talking to their clients about heart health. She noted that it was an extremely successful campaign because people were hearing the message from each other. Nagle said to Bauerle, “My guess is, it wasn’t much of a science message from the hairdressers.” “Correct,” Bauerle replied.

In Lefebvre’s opinion, academic programs need not be adding social media or other communication courses to their curricula. What they can do, however, is remind their students that they were people before they became nutritionists or biologists. Lefebvre suggested asking instructors to include graded social media assignments in their courses—for example, have students in a nutrition course start blogs, with part of the course grade being based on how many readers they attract to their blog over the course of a semester. The goal of these assignments, he said, would be not simply to produce blogs, but to build readerships and begin to develop a community of people who are learning how to talk about nutrition in a way that people understand.

This page intentionally left blank.