“Food is so much more than a plate of nutrients. . . . When it’s done right, food is well-being.”

—Sonya Grier

The goal of the first session of the workshop, moderated by Sarah Roller of Kelley Drye, planning committee chair and member of the the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Food Forum, was to describe the current state of the science concerning the role of consumer education, health communications and marketing, commercial brand marketing, health literacy, and other forms of communication in affecting consumer knowledge and behavior with respect to food safety, nutrition, and other health matters.

Food is so much more than a plate of nutrients, Sonya Grier, American University, stated in her opening presentation. Rather, she suggested, it is love; it is nurturance; it is comfort; it is a gift. “When it’s done right, food is well-being,” she said. Grier set the conceptual stage for the remainder of the workshop by arguing that food literacy should be considered within the broader context of food well-being. Decision making related to food is complex, she noted. Many different factors drive people’s choices—not just knowledge about nutrition, but also how one has been socialized around food (e.g., whether one grew up eating dinner at the table or going out for fast food), how food is marketed (which influences attitudes and behaviors), whether and which foods are available (e.g., the proximity of grocery stores), and policies concerning food (e.g., how many fast food restaurants are allowed in one’s neighborhood). In Grier’s opinion, gaining a better understanding of how people behave with respect to food will require examining all these factors and how they interact. The notion of food well-being resonated with many other speakers.

Building on Grier’s talk and drawing on lessons learned from the field

of health literacy, Cynthia Baur, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), explained that food literacy is not only knowledge about food and eating but also a range of skills related to what people understand about and do with the information being communicated. Baur described how decisions about food are not always made rationally or logically; rather, they may happen “unconsciously in a very emotional way.” A goal of food literacy, she suggested, should be to bridge the gap between what experts know and want to communicate and what consumers know and want. But Baur emphasized that communication does not happen by pushing messages at people. It happens, she suggested, when people—the audience or receivers, in communication terms—understand and make meaning from those messages. Closing the communication gap requires starting with the audience, or consumer; thinking about the consumer’s perspective, experience, and needs; and finding solutions that help the consumer, rather than serving the communicators’ organizational or other needs. These steps are supported by communication and health literacy research, Bauer noted.

FOOD LITERACY AS A PATH TO FOOD WELL-BEING1

In discussing food literacy in the broader context of food well-being, Grier spoke about (1) the nature of the challenge being addressed at the workshop, (2) the concept of food well-being as the end goal, (3) the origin and dimensions of the food well-being model, including food literacy as one dimension of food well-being, and (4) the interaction of the different dimensions of food well-being.

The Nature of the Challenge

The complexity of the challenge addressed at the workshop stems from the many different consumer education, scientific communication, and social and commercial marketing factors affecting not just what consumers know about food, Grier explained, but also how they act on that information. “We are talking about a very large and variant terrain,” she said.

Compounding the challenge is what Grier referred to as “the food paradox.” People are increasingly food-centered, with an entire industry having grown around food television programming and celebrity chefs and with the rising popularity of a wide range of eating styles (e.g., veganism, paleo diets, gluten-free foods). Additionally, there has been a growing focus on the relationship of food to health and a shift in ideology so that many people think of food as medicine. Yet at the same time, Grier observed, Americans are spending less time planning meals, preparing food, and eat-

______________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Dr. Grier.

ing together. Therefore, she said, while becoming more interested in food, people are actually becoming more disconnected from it.

Another paradox, Grier observed, is that the population has become increasingly obese even as people have become increasingly obsessed about fat, calories, and body mass index (BMI). For example, people eat entire boxes of fat-free cookies while counting calories. At a global level, obesity and related diseases coexist with hunger and food insecurity. Again, this paradox, or disconnect, points to “a lack of a healthy relationship with food,” Grier said. She emphasized the importance of understanding this unhealthy relationship.

The Concept of Food Well-Being

The concept of food well-being originated at a conference on Transformative Consumer Research, where Grier co-chaired a session on food and health. The session involved a diverse group of 12 international consumer researchers with varied approaches (which included experimentalists, cultural theorists, qualitative researchers, behavioral decision theorists, information processing researchers, and modelers) plus an epidemiologist, who was considered an “out-of-field” researcher. The researchers spent 2 days brainstorming on the state of knowledge in the topic area, Grier reported, highlighting theories, identifying research gaps, and beginning collaboration on a paper based on their deliberations (Block et al., 2011). The out-of-field researcher was epidemiologist Shiriki Kumanyika. Her statement that “No one sits down to eat a plate of nutrients” guided the remainder of the conference, Grier recalled, and led to the emergence of the concept of food well-being: that food provides not only physical but also emotional and psychological nourishment. Grier noted the many rituals associated with food and how eating is “something you do with your family.”

Shifting the paradigm from the notion that food equals health to this notion that food equals well-being appears to be a small shift, but it is one with many implications, Grier explained. Instead of being focused on the functions and medicinal properties of foods, food well-being calls for thinking about how food fits into people’s broader lifestyles. As opposed to a paternalistic view that entails telling people that a food is good or bad, Grier said, food well-being calls for thinking about people’s goals and what they want to get from foods. Rather than restraint and restriction, for example—instead of saying, “Don’t eat this” or “Don’t eat too much of that”—food well-being takes a more positive approach. It involves thinking about how consumers view foods as pleasurable and as an important part of their lives, Grier explained. The focus is not on calories and weight but on how food is embedded in and contributes to people’s lives.

For marketers, Grier noted, food well-being requires thinking about

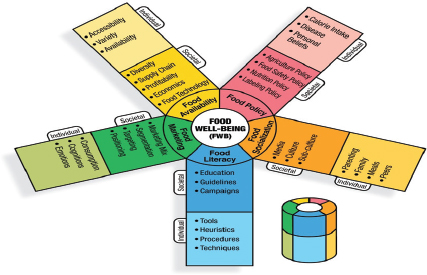

FIGURE 1-1 The food well-being model and its five dimensions.

SOURCE: Presented by Sonya Grier on September 3, 2015. Republished with permission of The Division, from Block et al., 2011, Journal of Public Policy and Marketing; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

the consumer’s relationship with food and how a positive relationship with food is essential to well-being. Additionally, she suggested, food well-being implies a richer definition of food—one that connects multiple ways of thinking about food. For example, although the slow food movement2 and food insecurity may appear to be distantly related concepts, Grier asserted that thinking about food as well-being provides an expanded conceptual framework for connecting such different food-related phenomena and practices.

The Food Well-Being Model

Grier explained that the food well-being model has five core dimensions: (1) food socialization, (2) food marketing, (3) food availability, (4) food policy, and (5) food literacy (see Figure 1-1) (Block et al., 2011). These

______________

2 Slow Food is a grassroots organization founded in Italy in the 1980s that has since spread worldwide. The movement promotes an alternative to fast food through the preservation of traditional and regional cuisine and encourages farming of plants, seeds, and livestock characteristic of the local ecosystem (www.slowfood.com). It was the first established component of the broader slow movement that advocates a cultural shift toward slowing down the pace of life.

five dimensions work together to describe and define a person’s relationship with food, she said. She discussed each in turn.

Food Socialization

Food socialization includes the processes by which people learn about food, Grier explained. It begins early, within one’s family, either implicitly (e.g., parents modeling cooking or eating behaviors such as eating large amounts of candy) or explicitly (e.g., parents telling children that they should not eat too much candy). In addition to the information that is thus passed along, family-level food socialization exerts a normative pressure that helps determine how a person will think about and relate to food in the future, Grier said.

Although these early family-level processes may be the most significant type of food socialization, there are others as well, Grier continued. Consumers live within societal structures, including ethnic rituals, media, and marketing. Grier stressed the importance of considering the interplay between how children are socialized within families and how these broader societal structures provide information and influence behavior.

Food Marketing

Grier described food marketing as the strategic use of product, price, and promotion (i.e., the “marketing mix” minus place) to influence consumer attitudes and behaviors concerning foods. Marketing has an important influence on what people eat, she stated. She explained that people make consumption decisions within an emotional context, often with little cognitive effort or awareness, such that something as simple as a picture on a box of food can influence how much of that food a person eats. She emphasized the need to consider how other factors, not just cognition, are at play in consumers’ decisions, and the emotional properties of food influence what people actually eat. “You have to think about people’s pleasure from food,” she said.

Food marketing influences consumer behavior not just at the individual level but also at the aggregate or societal, level, Grier noted. She pointed to all the meta-messages that consumers receive, or do not receive, from multiple types of ads about certain food products. While consumers see many energy-dense products being advertised, for example, they normally do not see fruits and vegetables being advertised. The aggregate effect of the products being marketed, the types of information provided, and the prices being charged have a major influence on the way people think about those products, Grier asserted. Based on her own research on marketing targeted to particular groups, she observed that these aggregate-level marketing mes-

sages can actually contribute to health disparities by giving different groups of people different types of information. While marketing contributes to the problem, however, she suggested that it can also contribute to the solution. She believes that both commercial marketing practices and social marketing (i.e., the use of traditional commercial marketing practices to achieve social goals) can support food well-being.

Food Availability

Food availability, a third core dimension of food well-being, is separated out from food marketing, Grier explained, because it is so important in terms of people’s access to food. People constantly face multiple decisions as to where they are going to obtain their food (e.g., from the farmers’ market versus different types of grocery stores). There are many different food sources, Grier noted, which vary with respect to prices, convenience, and, sometimes, food quality. Additionally, she said, consumers must select among available food options that vary in processing, taste, and healthfulness.

As with the other dimensions of food well-being, Grier explained, food availability has both individual and societal components. The built environment determines access to healthy foods not just for individuals but for entire neighborhoods. Grier pointed to the many food “deserts” or “swamps” where people have no or limited access to healthy foods. She noted that these neighborhood-level differences in accessibility can have a strong influence on consumers’ ability to achieve well-being in their relationship with food. She observed that, in addition to these neighborhood-level influences, the economic environment influences food availability as well.

Food Policy

The fourth core dimension of food well-being includes policies related to agriculture or food production, food pricing, food safety, and food labeling, all of which have a major impact on whether consumers can achieve food well-being, Grier stated. At the individual level, she explained, policies can impact food well-being by allowing consumers to make informed decisions and give them peace of mind in their choices. At the societal level, policies such as dietary guidelines can contribute not only to food well-being but also to environmental sustainability or, as Grier described it, “societal food well-being.”

Food Literacy

Grier remarked how ample research has shown that knowledge about food and nutrition can improve the quality of consumption choices. “But we also know that knowledge alone is not enough,” she said. She emphasized the importance of motivation, ability, and opportunity to apply that knowledge when making food choices. Considering this broader context, she defined food literacy as “understanding nutrition information and acting on it in a way that is consistent with nutrition goals and with food well-being.”

At the individual level, food literacy has three main components, Grier explained. First is conceptual knowledge, which is the acquisition and comprehension of food-related information (e.g., learning how to prepare food, learning which foods contribute to certain types of outcomes). Most past thinking about food literacy has focused on such conceptual knowledge, Grier suggested. The second main component of individual-level food literacy, she continued, is procedural knowledge. That is, what does one do with ingredients? How does one prepare a meal? How does one cook a particular dish? People learn “scripts” for how to cook foods or how to behave when in a fast food versus a sit-down restaurant, for example, and learning these scripts contributes to the way they understand food. Motivation to participate is the third main component of individual-level food literacy. Grier referred to remarks she had made at the outset of her presentation with respect to people being interested in food but not being motivated enough to do what is necessary to apply their conceptual or procedural knowledge (e.g., being interested enough to buy something but not motivated enough to make it themselves). She noted that many different levels of motivation and barriers come into play in different food-related contexts that prevent consumers from applying their knowledge.

With respect to societal-level food literacy, Grier emphasized that guidelines, campaigns, and educational initiatives serve an important role in informing people about how to incorporate food into their lives. She explained that the food well-being model involves reframing these approaches so they are focused not only on food as health but also on what food means to the target consumer.

Interaction of the Dimensions of Food Well-Being

“Food literacy does not exist alone,” Grier said. Rather, all five core dimensions of food well-being intersect. For example, she said, consider two children, one who grows up in a family that cooks together and eats meals at the dinner table every night, and another whose family goes out every night and buys fast food. These different socialization processes, Grier

explained, lead to different levels of food literacy. They also may affect how children respond to food marketing, as well as how different policies and guidelines influence their choices and behaviors. Grier emphasized the comprehensive understanding that derives from considering the intersection of the dimensions of food well-being.

Grier speculated how some of her own past research might have yielded more comprehensive results if she had considered these different dimensions and their intersection. She mentioned a 2003 ad for McDonald’s with the message, “When will she have her first french fry?” The ad, she recalled, triggered her interest in fast food norms. When she entered the field, most researchers were focused on fast food marketing to children. But she wondered whether marketing to parents might influence children indirectly by socializing them with regard to what is appropriate.

In a cross-sectional study of eight U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) health centers in medically underserved communities, Grier and colleagues (2007) looked at how marketing strategies, product, price, promotion, and access influence parental attitudes and social norms around fast food consumption and how those attitudes and norms, in turn, influence the amount of fast food parents feed their children. The researchers interviewed caregivers of children aged 2 to 12 years and collected the children’s height and weight measurements (for BMI calculations). They found that increased exposure to fast food promotion was associated with parents’ beliefs that eating fast food is normal, and that this social norm (“all my friends feed their kids fast food”) led to their children’s more frequent consumption of fast food. Additionally, they found that, compared with white and Asian parents, black and Hispanic parents reported greater exposure to fast food promotion, greater access to fast food, and higher levels of fast food consumption by their children. Grier suggested that if that study had incorporated a food well-being model—that is, if she and her collaborators had collected information not just on food marketing and availability but also on food literacy (e.g., parents’ skill levels in food preparation), socialization (e.g., how permissive parents were with their children), and policy (e.g., related to zoning and fast food prevalence)—they would have presented a much stronger and larger picture of how the people participating in the study related to food and how interventions could be developed to enhance their food well-being.

Implications and Concluding Thoughts

To summarize, Grier reiterated that a food well-being model highlights the importance of understanding what food means to consumers. She noted that the model incorporates a broad range of influences across disciplines to better organize the complexity of the food decisions people make and

the ability of food to contribute to social, psychological, and physical well-being. It embeds food literacy within the broader context of people’s relationship with food and highlights the need to consider the interrelationships of the different dimensions of food well-being. Grier expressed hope that a food well-being framework would stimulate new ways of thinking about how consumers’ relationships with food can be transformed—through consumers’ own choices, marketers’ practices, and public health efforts and policy initiatives. “We hope that it will help us move beyond just educating consumers about the nutritional aspects of food,” she said, and “to think more critically about the whole plethora of messages that they receive.”

A HEALTH LITERACY PERSPECTIVE ON CONSUMERS’ FOOD EDUCATION, SKILLS, AND BEHAVIOR3

Baur began by suggesting that there are many similarities between the health literacy paradigm and the food well-being model described by Grier, but with differences in terminology.

The Complexity of Health Literacy

Baur posed the question, “What is so confusing or hard to understand about food and nutrition?” She cited several concepts that experts consider when trying to develop messages about food and nutrition, including nutrition quality, dietary intake, food preparation, and healthy eating. She suggested that, although the words “healthy” and “eating,” for example, are not particularly difficult concepts by themselves, “healthy eating” is a complex concept open to different points of view or interpretations.

Moreover, Baur explained, health literacy is not just about confusing or complex words; it is also about numbers, as a great deal of health information is heavily laden with numbers that may be difficult or unfamiliar. She showed the audience some numbers and abbreviations from food products in her own kitchen cupboard: “only 5 g of sugar,” “serving size 2 oz (56 g—about 1/8 box),” “sodium 0 mg 0%,” and “2,000 calorie diet.” “I am somebody who spends a lot of time thinking and studying and learning about health information,” she said. “To be honest, I am not really sure what I am supposed to do with these pieces of information.”

Added to the numeracy challenge, Baur suggested, is that the messages being imparted exist in a complex system. “People are having to make these micro-decisions within the midst of a very complex environment,” she said. She asserted that communicators need to be aware of the “full spectrum”

______________

3 This section summarizes information presented by Dr. Baur.

of what people know and do in relation to food, ranging from being concerned about food safety to balancing eating and physical activity.

Further compounding the challenge of understanding food and nutrition is that food has risks and benefits, Baur observed. Among its risks, food can be contaminated with pathogens, she noted, or places or settings where food is prepared or eaten can potentially expose people to health risks. Additionally, some behaviors can generate additional risks, and certain food choices are associated with risks of poor health. Baur referred to the benefits of food cited by Grier, which include pleasure and enjoyment; good health and nutrition; and the bonding, traditions, and other connections and experiences associated with food. These risks and benefits need to be weighed together, Baur said. Choices about food are not always made on a rational and logical level; they are, she said, “happening unconsciously in a very emotional way.”

Lessons from Health Literacy

For Baur, lessons from health literacy can inform the food literacy discussion, helping social scientists understand why people know less than experts expect and would like them to know, why people do not appear to care much about the food-related messages they receive, and why people are not doing what experts recommend that they do. She reminded the workshop audience that the field of food and nutrition is not the only field in which experts are concerned about what people do not know. Experts in such fields as medicine, public health, and dentistry are equally concerned, she observed, and communicators often are dealing with a large gap between what these experts and lay people understand, expect, and want to happen.

Adult Literacy, Numeracy, and Health Literacy Baselines

At an even more basic level, few adults have no literacy skills at all, Baur explained, and most fall somewhere on a spectrum of skills, ranging from very low to somewhat high. In the most recent study of U.S. English-speaking adults, conducted by the U.S. Department of Education in 2012, the average adult literacy score was 270 on a 500-point scale (Goodman et al., 2013). That score is below the international average of the 23 OECD countries that participated in the study. Only 12 percent of the adult U.S. population scored at the highest level of literacy. Based on the results of this survey, at least 18 percent of the adult U.S. population would struggle with average literacy tasks, such as putting two pieces of information together, paraphrasing something, comparing and contrasting, and drawing a very low-level inference. Most of these average literacy tasks are necessary for

doing many of the things Grier had described with respect to food well-being, Baur observed.

Unfortunately, the outlook on numeracy is not even as good as that on literacy, Baur continued. The average numeracy score on the U.S. Department of Education survey was 253 (out of 500), which again was below the international average. Only 9 percent of respondents scored at the highest level of proficiency. Based on the survey results, at least 30 percent of the adult U.S. population would struggle with average numeracy tasks, which relate to explicit or visual math content with few distractors; two-step calculations with whole numbers and common decimals, percents, and fractions; and simple measurements. Again, according to Baur, these are skills necessary for many of the things Grier had discussed as contributing to food well-being.

The only national assessment of health literacy skills that has been conducted in the United States was part of a 2003 U.S. Department of Education study. The results were published in 2006 (Kutner et al., 2006). The assessment was based on a specific set of tasks related to health and health information. Only 12 percent of those surveyed scored at the highest proficiency level; most (53 percent) scored at an intermediate level; and about one-third scored at a basic (22 percent) or below basic (13 percent) level. An example of an everyday health literacy task is figuring out the cost of a health insurance premium from a form; individuals who could do this successfully were scored as proficient. Bauer remarked that having basic or below basic health literacy skills affects a person’s ability to find, understand, and use health information.

What Is Health Literacy?

Baur described health literacy as encompassing

- how people get information;

- how they process that information cognitively;

- how they understand that information, or the meaning they make of it; and

- what they decide.

She suggested that behavior change should be considered separately from health literacy because people can have many reasons for following or not following health behavior recommendations.

Health literacy builds on general literacy and numeracy by encompassing cultural and contextual factors; beliefs, experiences, and preferences; and knowledge of the body and how it works, as well as knowledge of science and how it works. With respect to science knowledge, Baur said,

“a lot of the information that we try and relay to the public really relies on an implicit understanding of how science works.” Given the data on literacy, numeracy, and health literacy, she questioned the extent of that understanding and how people interpret a statement such as “science supports . . .” and messages about risk. The notion of risk is in almost every message the public receives from health communicators, she observed. But being told that one is “at risk for something” or “at increased risk” invokes potentially conflicting or distracting meanings for people, she noted.

Baur suggested thinking about health literacy from a public health ecological perspective, whereby communication and health literacy are embedded in a complex set of interactions and results. Doing so makes health literacy more difficult to study but better reflects reality, she said, citing the public health ecological model of Maibach and colleagues (2007). In this model, cognition, beliefs, messages, skills, and other individual factors that influence health literacy are part of a larger overall picture that also includes marketing practices, food availability, social norms, and other aggregate-level attributes. Baur noted the complementarity between this model and Grier’s food well-being model.

Baur told the workshop audience she dissuades people from thinking that health literacy can be measured by readability formulas because such formulas are too simplistic. She suggested that, although measuring readability may provide some information about the material, the scores are not helpful when one thinks about communication in terms of “meaning making,” which is a fundamental principle of communication. Again, she said, although “healthy” and “eating” are familiar terms to most people, combining them into “healthy eating” creates a complex and potentially unfamiliar concept that becomes difficult to communicate because of people’s experiences, beliefs, and values.

Baur noted that researchers have reported several different types of outcomes associated with limited health literacy (Berkman et al., 2011). With respect to health outcomes, she said, limited health literacy hinders people’s ability to take medications appropriately and interpret labels and health messages, and is associated with lower health status and quality of life and increased mortality, particularly among seniors (Berkman et al., 2011). With respect to outcomes related to health services, limited health literacy has been associated with more frequent hospitalization and rehospitalization, greater use of emergency care, and lower likelihood of influenza immunization. In terms of knowledge and comprehension, Baur observed, limited health literacy has been associated with less knowledge about almost every health topic studied.

Baur reiterated the importance of starting communication “where people are”—with what people know and can do in the moment. She suggested that health communicators need to consider the literacy and numeracy skills of their audience and then adjust recommendations accordingly. The

education sector is an important partner in helping to make those adjustments, she asserted.

Too often communicators focus on the “push side,” according to Baur. That is, they have a message they want to deliver, they format it, and then “push” it out. But communication does not happen until the communicator and audience reach a shared understanding about the intended meaning of a message, Baur explained, which means a single exposure to information usually is not enough to achieve understanding. When someone is looking at a fact sheet on www.cdc.gov at 11 PM at night, for example, the communicator is not sitting by that person’s side saying, “I did not really mean that. I meant this instead.” Verbal communication through dialogue, in contrast, allows people to say, “I don’t get it. Could you give me an example? Could you show me what you mean? Could you restate it?” Baur emphasized the dynamic nature of communication—written and oral—and the importance of building opportunities into that process to correct for miscommunication and misunderstanding.

Questions to Consider

Based on her work in health literacy, Baur posed a list of questions for workshop participants to consider with regard to food literacy. First, she asked, what do experts think people should know about food, and do experts from different disciplines agree? Baur noted that many different disciplines were represented at the workshop and cautioned that disagreement and lack of clarity about what experts want people to know have several consequences. Multiple, confusing, and potentially conflicting messages are left to the audience to sort out, she noted. People can end up confused and misinformed, throwing up their hands and relying instead on what they already know and what their friends and others in their networks tell them. Baur cautioned that communicators need to be realistic and understand that people are not going to sit down and study materials for 30 minutes. When they go to the CDC website, for example, if they are not provided with relevant information immediately—information that they find interesting, useful, and understandable—they leave the site. Ultimately, Baur observed, if people do not understand a message, they probably will not follow the recommendation. Often when people appear “irrational” or are labeled “illiterate” because they do not understand, she suggested, it is the communicator who is at fault for not presenting the information clearly.

Next, Baur asked, how well do experts’ expectations match people’s interest in knowing and capacity to know, and do experts expect people to absorb too much knowledge that is not useful? Communication research shows that people’s interest in something directly relates to how much attention they will give a communicator. “Attention is really key,” Baur emphasized. “You cannot really deliver a message very effectively if you do

not have people’s attention.” She mentioned psychologist Steven Pinker’s “culture of knowledge” notion—that experts incorrectly believe others know what experts know. When experts’ expectations are misaligned with those of their audience, she explained, people may end up receiving too much irrelevant information. They become confused and, again, rely on prior knowledge, may ignore what experts have told them, and run the risk of being labeled “irrational” or “illiterate.”

Baur listed several skills-related questions worth considering. What do experts think people need to do to eat a healthy diet? That is, what are the skills that people need to translate knowledge into behavior? Do people already have these skills, or do they need to develop them? If the latter, who is going to develop them, and how? Baur explained that health literacy research has shown that people tend to underestimate the number and complexity of tasks necessary to follow directions or recommendations successfully. She cautioned that scientifically accurate recommendations can be behaviorally unrealistic, with people being exposed to messages encouraging behaviors in which they are unable to engage. When a large mismatch occurs, she said, people again end up being labeled “nonadherent,” “noncompliant,” and sometimes even “stupid.”

Baur noted that the CDC uses a tool, the Clear Communication Index (www.cdc.gov/ccindex), to help develop behaviorally realistic communication materials. Although communication has many other dimensions besides clarity, she said, such as interest and motivation, the focus of the Index is on clarity because the CDC wants to ensure that, as a sender of information, it is transmitting what is at least a clear message. She illustrated the use of the Index with an example from food safety, in which what would otherwise be a bundle of everyday food safety behaviors is broken down into four separate, simple steps (see Figure 1-2). Each step is a single-word action: (1) clean, (2) separate, (3) cook, and (4) chill. Each of these steps depends on a mix of knowledge and skills that people must use in the appropriate sequence to ensure food safety.

From a health literacy perspective, said Baur, several research and practice questions about food literacy relate to individual, organizational, and social/environmental levels of analysis. At the individual level, what do people themselves need to do to cultivate the knowledge and skills necessary for eating in health-promoting ways? At the organizational level, how can organizations that prepare and deliver messages ensure that their messages are clearly expressed, relevant, accurate, and supportive of skill development with respect to eating in health-promoting ways? At the social or environmental level, how can environments be designed so that people can navigate food choices and eat in health-promoting ways?

In conclusion, Baur raised two general research questions about the intersection of food literacy and health literacy. First, how much does health

FIGURE 1-2 An everyday “bundle” of food safety behaviors broken down into four simple actions.

SOURCES: Presented by Cynthia Baur on September 3, 2015; CDC, 2015b.

literacy contribute to food knowledge and skills? Second, how much do food knowledge and skills contribute to overall goals related to food and healthy eating? Baur also offered a “final recommendation and caution”: that health literacy insights should be used to highlight audiences’ or end users’ perspectives, experiences, and needs rather than to justify another traditional education campaign. The goal, she said, should be to illuminate practical solutions that help audiences understand and use information, not solutions that serve organizational needs. “Please don’t use health literacy to justify an overly rational or education-heavy solution,” she concluded.

Following Baur’s presentation, Sarah Roller moderated a panel discussion with Grier and Baur. This section summarizes that discussion.

Nutrition Versus Food Safety Messages: Which Are “Easier” to Communicate?

Roller opened the discussion by asking Baur whether there are differences in the communication challenges associated with messages related to nutrition, diet, and health versus messages related to food safety. Specifically, she asked whether it is easier to communicate messages about food safety than those about nutrition, diet, and health. Based on her own involvement with the writing of recall-related information, she observed that such messages are usually fairly simple. Although they may mention

salmonella or listeria, for example, consumers need not know very much about the contaminant to make a decision or take action.

“I don’t think any of it is easy,” Baur replied, but some food safety messages may have greater clarity. Recalls usually involve discrete, one-time-only actions, she noted, such as, “throw out x” or “return x.” With respect to skills, actions, and behaviors, she suggested, telling people they need to do something only once is easier than telling them they need to perform an action, or several actions, multiple times a day or multiple times a week over a lifetime.

Grier added that the way messages are framed—specifically whether they are framed in terms of disease prevention or health promotion—can have an impact on consumer behavior. People are motivated to respond to food safety messages because they do not want to get sick, she noted, whereas messages about eating for health promotion are more challenging. Baur agreed that food safety messages tend not only to be simpler but also to resonate with consumers. She mentioned a colleague’s research findings indicating that people are willing to listen to messages and follow recommended behaviors when the messages relate to protecting their children or families.

Rational Thought, Emotion, and Motivation

An audience member pointed out that billions of dollars are spent on food marketing and that much of this marketing is not aimed at conscious, rational thought. Rather, it is aimed at consumers’ feelings, with the goal of eliciting an emotional reaction, not a synthetic understanding of technical information. The audience member wondered whether “we are missing the boat” by focusing on literacy rather than emotion, and asked if there are better ways to reach consumers.

Grier replied that from a food well-being perspective, designing interventions calls for thinking about more than literacy. She reiterated that literacy exists within the broader context of food well-being and stressed the importance of the interaction of the five dimensions of the food well-being model. People’s understanding of food is also influenced by food marketing, the availability of foods, and the way a person is socialized at home or by the media, she explained. Thinking about all of those factors in combination will require a multidisciplinary effort, in her opinion. She encouraged researchers to step out of their “comfort zones.”

Education, Behavior, and Sending Simple Messages

Tim Caulfield, workshop presenter, asked the panelists whether there are any data on education and food behavior. He noted that the relationship

between education and behavior in other realms, such as complementary and alternative medicine, is complex, and that more education does not necessarily mean more rational behavior. Additionally, he asked whether there are any data supporting the notion that people are more likely to fall back on their own education when messages are complicated. In his opinion, the answer is to send simple, clear messages. But he was curious about what data exist to support that idea.

“I don’t want to leave the impression that a simple, clear message is going to carry the day,” Baur replied. “There is no magic elixir in a simple, clear message.” However, she stated it is difficult to think about other effective communication strategies without having a simple, clear message to send. She observed that often when she deconstructs the pieces of health information, she finds that even the communicators may not be completely clear about the message they are trying to send. She has been involved with a few studies in which she and colleagues have used the CDC’s Clear Communication Index to convert health material with multiple messages or with no one clear message into a design that draws attention to a single main message. She said, “We do all these things to make it almost impossible to miss the main message.” She noted that preliminary evidence from these studies suggests that design makes a big difference in whether people can actually understand and process the information the communicator intends to send. Even after these various clear communication techniques are applied, however, people are still distracted by other things. “Even when I do my absolute best to design something in the clearest way possible using these science-based criteria,” Baur said, “I am not getting 100 percent comprehension in the way that I intend as the sender.” With respect to the role of education, she stated that there is a strong correlation between education and health knowledge, but it is not one for one. She suggested being mindful that relying on print to deliver health information challenges people who lack strong literacy skills—a significant portion of the U.S. adult population.

The Role of Commercial Food Marketing in Fostering a Healthy Relationship with Food

Roller asked Grier whether commercial food marketing has a role to play in fostering a healthy relationship with food. “I think so,” Grier answered. If not, given the magnitude and scope of commercial marketing, she said, “then we are kind of doomed.” The public health infrastructure does not have the resources to reach consumers in the same way, in her opinion. She noted that companies have big data and can use those data to understand smaller segments of the population in ways that allow them to develop better interventions. With their broad reach, moreover, companies

such as Walmart can extend their messaging to people that nonprofit or socially oriented organizations are unable to reach. Food marketing is such a prevalent part of the food environment that if companies do not contribute, Grier suggested, it will be difficult to effect change.

Baur agreed. She emphasized that exposure to messages matters and observed that people are much less likely to be exposed to messages delivered by the CDC, for example, than to those from other sources with which they are more familiar. She said, “I think you could have productive partnerships if you can align the interests.”

Considering an Even Broader Context Than Food Well-Being

Kristen Harrison, workshop moderator, mentioned a book by Everett Rogers, Diffusion of Innovation, in which the author describes a water boiling campaign in Peru. The goal of the campaign was to reduce the pathogen load in the water. The project was a “terrible failure,” Harrison said. It was later discovered that residents in that part of Peru, as in other areas of the world, believed that foods were inherently either cold or hot regardless of their actual temperature. Cold foods were believed to be for hardy people and hot foods for feeble, weak, or recovering people. The boiling of water was believed to turn “raw” water, considered a cold food, into a hot food, even if the water was cooled after it had been boiled. Because of these beliefs, people did not want to drink the boiled water because they did not want to be socially stigmatized. Harrison asked the panelists to take the concept of food well-being one step further and consider its broader “social well-being” context. When social well-being comes into direct conflict with food well-being, as it did with the water boiling campaign in Peru, what can be done to encourage people to make food well-being a priority?

Grier responded that it may not be possible to change people’s priorities with respect to food well-being because at the core of the model, food well-being is about people’s own goals. “I cannot tell you what your goals are about foods,” she said. At the same time, there exists a notion of societal health, along with questions about how individuals can be stewards of societal health. Grier suggested as an important topic for further research identifying interventions that balance individual behavior with societal health.

The Role of Qualitative Research in Gaining a Better Understanding of Food Well-Being

Linda Neuhauser, workshop presenter, asked the speakers about messages that resonate with parents, particularly messages about food well-being. Grier replied that she and her colleagues have not yet done research in that area. She suggested that qualitative research would be the next step

toward understanding how parents perceive food well-being and what type of information they need to make decisions based on that concept. Such research would help in understanding how the concept of food well-being fits in the context of people’s lives, as opposed to embedding it in a preconceived context and studying how people relate to it as part of a survey or experiment. Grier suggested further that the same approach might be a helpful way to begin to answer the question raised by Harrison about food well-being in the broader context of social well-being.

Considering the Complexity of People’s Lives

Wendy Johnson-Askew, workshop moderator, told of being a dietician many years ago and having a patient say to her, “The only label I read is ‘two for a dollar.’” Given the reality of people’s complex lives, she asked how messages that resonate can be developed and how the context of people’s lives can be measured and captured. She mentioned a study showing that individuals prioritize outcomes according to their immediacy. Something that would kill a child, for example, was considered more important than something like obesity with a long time horizon.

Grier called for multidisciplinary teams of researchers and more cross-cultural thinking. People who live in areas where crime is a major issue, for example, may not be thinking about what they are eating. Grier asserted that communicators need to recognize this reality and understand that their messages may need to differ based on the target audience’s context. She suggested that public health experts need to think about segmenting the population, much as marketers do, with respect to literacy, socialization, access, and other factors.

Baur mentioned Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow because it collects 50 years of research on cognitive biases that lead people to make what are often labeled “irrational” decisions. “They are not irrational if you understand why people think about problems the way they do,” she said. She reiterated the importance of starting with where consumers are in their perceptions, beliefs, and values. If her presentation had one main message, she said, it is to be realistic, shed expectations, and “meet people where they are.” In her opinion, researchers have yet to integrate that way of thinking into their projects. She encouraged researchers to ask more complex questions and develop projects that account for more of the many factors that drive people’s decision making.

This page intentionally left blank.