2

Improving Care for Socially At-Risk Populations

PERFORMANCE OF PROVIDERS DISPROPORTIONATELY SERVING SOCIALLY AT-RISK POPULATIONS

As described in the committee’s first report (NASEM, 2016), socially at-risk populations include individuals with social risk factors for poor health outcomes such as low socioeconomic position, social isolation, residing in a disadvantaged neighborhood, identifying as a racial or an ethnic minority, having a non-normative gender or sexual orientation, and having limited health literacy (NASEM, 2016). Although these populations receive care from a wide range of providers, they are disproportionately represented among the patients treated by a small subset of providers, including safety-net hospitals, minority-serving institutions, critical access hospitals, and community health centers (CHCs) (Bach et al., 2004; Jha et al., 2007, 2008). Evidence suggests the performance of these providers may differ systematically from providers serving the general population.

Inpatient Care

Safety-net providers “organize a significant level of health care and other related services to uninsured, Medicaid, and other vulnerable patients” (IOM, 2000, p. 21). Safety-net hospitals defined as those with a high proportion of Medicaid or low-income patients on average provide lower-quality care (i.e., adherence to recommended care processes) for myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, community-acquired pneumonia, and colon cancer (Culler et al., 2010; Goldman et al., 2007; Rhoads et al., 2013; Ross et al., 2007). Patients at safety-net hospitals also report poorer experiences of care compared to patients at non–safety-net hospitals (Chatterjee et al., 2012; Mouch et al., 2014). On the other hand, one study defined safety-net hospitals as members of the National Association of Public Hospitals and Health Systems (now America’s Essential Hospitals), because members self-identify as safety-net providers and have many characteristics of safety-net hospitals, including serving a large proportion of uninsured and Medicaid patients and mostly having public or nonprofit ownership (Marshall et al., 2012). This study found no significant differences in the quality of care for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), pneumonia, and surgical care between safety-net and non–safety-net hospitals (Marshall et al., 2012). Two studies examined trends over time. One study examined disparities in quality of care (Werner et al., 2008), and the other examined disparities in patient experience (Chatterjee et al., 2012); both found that safety-net hospitals improved more slowly compared to non–safety-

net hospitals, resulting in a widening disparity in performance between safety-net and non–safety-net hospitals over time. Disparities in patient safety indicators, mortality rates, and readmission rates at safety-net hospitals compared to non–safety-net hospitals are more mixed (Mouch et al., 2014; Ross et al., 2007, 2012; Wakeam et al., 2014). Given the lack of agreement about the operational definition of a safety-net hospital, differences in measures used to define safety-net hospitals may account for some of the inconsistency in findings (Marshall et al., 2012; McHugh et al., 2009).

Minority-serving institutions are frequently defined in the literature as providers with a proportion of racial and ethnic minority patients in the top decile and are often restricted to blacks or Hispanics. Compared to hospitals with fewer black patients, black-serving hospitals (top decile proportion of black patients) as a group provide lower-quality care for pneumonia, AMI, and lower-extremity vascular procedures (Barnato et al., 2005; Jha et al., 2007; Mayr et al., 2010; Regenbogen et al., 2009). Black-serving hospitals also have poorer patient safety outcomes (Ly et al., 2010), higher readmission rates (Joynt and Jha, 2011; Tsai et al., 2015), and poorer health outcomes for patients with AMI (Barnato et al., 2005; Skinner et al., 2005). Patients at black-serving hospitals also reported poorer experiences of care (Brooks-Carthon et al., 2011). Studies of providers serving high proportions of Hispanics, Asians, and other racial and ethnic minority patients show similar patterns of disparity (Hasnain-Wynia et al., 2010; Jha et al., 2008; Rangrass et al., 2014). Notably, hospitals that disproportionately serve racial and ethnic minority patients perform worse on average regardless of an individual patient’s race (Gaskin et al., 2008; Joynt and Jha, 2011; Lopez and Jha, 2013). In other words, both white and non-white patients at minority-serving institutions receive poorer quality care and have worse outcomes compared to white and black patients at non-minority-serving institutions (Gaskin et al., 2008; Joynt and Jha, 2011; Lopez and Jha, 2013). Evidence on the quality of care at nursing homes with a high proportion of black residents is inconsistent (Chisholm et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2006).

Critical access hospitals refer to rural safety-net providers—specifically, smaller, rural, acute care hospitals eligible for additional federal funding to provide care to patients who reside in rural areas and have difficulty accessing inpatient care (Joynt et al., 2011, 2013). Compared to both non–critical access hospitals generally and to urban acute care hospitals specifically, critical access hospitals provide lower-quality care on average and have higher mortality rates for AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia (Joynt and Jha, 2011; Joynt et al., 2013; Lutfiyya et al., 2007).

Together, the literature described above suggests that hospitals disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations may provide lower-quality care and have worse patient outcomes compared to hospitals serving the general population on average. However, there is also evidence of substantial variation in performance among these providers. For example, Gaskin and colleagues (2011) found that the performance of minority-serving hospitals varied substantially across measures and by race and ethnicity. Additionally, they found both positive and negative associations between the proportion of black discharges and indicators of mortality and patient safety. Other studies have shown that there is substantial overlap in performance between minority-serving hospitals and white-serving hospitals, and substantial numbers of minority-serving hospitals perform well, achieving performance scores on par with the top non–minority-serving hospitals (Jha et al., 2008). At the same time, several studies of low-performing hospitals for care processes for AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia (those performing in the bottom decile or quartile) reported that these hospitals are more likely to serve disproportionate

shares of socially at-risk populations—racial and ethnic minorities and low-income patients—and identify as safety-net hospitals (Girotra et al., 2012; Jha et al., 2011; Popescu et al., 2009).

Ambulatory Care

In contrast to inpatient facilities, literature suggests that the performance of safety-net and minority-serving providers of ambulatory care is more mixed. Safety-net primary care providers include community health centers and minority-serving providers. CHCs, also known as federally qualified health centers, and federally funded health centers provide primary care and preventive services to socially at-risk populations such as Medicaid patients, uninsured patients, migrants, and the homeless. These health centers are eligible for increased reimbursement rates for Medicare and Medicaid (HRSA, n.d.). Several studies reported that patients of CHCs and their look-alikes (providers with similar characteristics but who do not receive federal grant funding) receive equal or higher-quality care and have lower utilization rates (i.e., emergency department [ED] visits, inpatient hospitalizations, preventable hospitalizations, and hospital readmissions) on average compared to patients accessing other providers (Goldman et al., 2012; Laiteerapong et al., 2014; Rothkopf et al., 2011). In contrast, one study reported that patients of physicians who reported high Medicaid case volumes had higher rates of hospitalization for two ambulatory care–sensitive conditions—chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumonia (O’Malley et al., 2007). As for minority-serving primary care providers, Lopez and colleagues (2015) found that Latino patients within a single large academic care network in Massachusetts who received care from primary care practices with a high proportion of Latino patients received higher-quality care for coronary artery disease and congestive heart failure compared to patients receiving care from practices with fewer Latino patients. Sequist and colleagues (2008) reported that the number of black patients treated by a physician was not associated with worse performance among diabetes patients. One study found that the quality of care did not differ between minority-serving and non–minority-serving dialysis facilities, but that patient survival was worse among minority-serving facilities (Hall et al., 2014). Literature from these ambulatory care facilities provides evidence of further variations in the quality of care among providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations.

Publicly Reported Performance Data

The committee considered using publicly reported performance data from providers relevant to Medicare beneficiaries—Medicare Hospital Compare hospital data and Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D Star Ratings health plan data—to identify high-performing providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations. To do so would have engaged the committee in original empirical research, uncommon in reports from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, especially given the time frame the committee faces. The committee identified several challenges to identifying universally high performers. As described in the literature (e.g., Gaskin et al., 2011; Girotra et al., 2012; Jha et al., 2005, 2008; McHugh et al., 2014), there exists substantial variability in performance across measures and practice areas within organizations and across time for all providers. Individual providers perform well and poorly on different measures and in different practice areas (Medicare.gov, n.d.). For example, Girotra and colleagues (2012) found that among all hospitals that reported performance on AMI or on heart failure from 2006 to 2008, 49 and 105 hospitals, respectively, that reported performance data in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital

Compare were consistently high performing from 2006 to 2008, and 88 and 147, respectively, were consistently low performing; only 18 hospitals were consistently high performing, and only 19 hospitals were consistently low performing for both AMI and heart failure. Similarly, Jha and colleagues (2005) found little correlation across measures of AMI, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia, and McHugh and colleagues (2014) found little consistency in performance as measured by either achievement or improvement across three quality domains—ED clinical process measures, inpatient clinical process measures, and patient experience measures.

Moreover, there is little stability in performance over time, such that a high performer one year may perform poorly the next. It is precisely for this reason that researchers frequently aggregate data across several years to establish average performance. Additionally, as CMS notes in a caveat about using the data for patient decision making, a provider’s performance on any individual measure or domain may not generalize to its overall performance (Medicare.gov, n.d.). Likewise, one study used a composite measure covering multiple domains (quality/process of care measures for AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia; 30-day readmission rates, in-hospital mortality; efficiency; patient satisfaction; and two survey-based assessments of patient care quality by chief quality officers and frontline physicians) to identify high-performing hospitals (Shwartz et al., 2011). However, because hospitals varied in their performance across measures and the measures were poorly correlated, hospitals that ranked highly on the composite measure were unlikely to be top performers (top quintile) in individual measures.

Given these challenges, the committee did not embark on original research and depended on the published literature described above. Therefore, the committee was unable to identify high- or low-performing providers if interpreted as universally high or low performers across all measures. As a result, the committee was also unable to identify high- or low-performing providers who disproportionately serve socially at-risk populations. Despite these challenges and as described above (e.g., Gaskin et al., 2011; Goldman et al., 2012; Greenberg et al., 2014; Jha et al., 2008; Laiteerapong et al., 2014; Lopez et al., 2015; Rothkopf et al., 2011; Sequist et al., 2008):

The committee found that some providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations achieved performance that was higher than their peer organizations and on par with the highest performers among all providers.

PRACTICES TO IMPROVE CARE FOR SOCIALLY AT-RISK POPULATIONS

The mechanisms underlying disparities in health care outcomes are complex and include both specific practices that occur during the provider–patient encounter and systemic differences that occur between treatment settings (Hasnain-Wynia et al., 2007, 2010). Disparities in health care outcomes occurring within the treatment setting may arise from differences in the quality of care received, which in turn may result from miscommunication, cultural misunderstanding, discrimination, and bias (IOM, 2003). Disparities in health care outcomes may also be attributable to between-provider mechanisms, which include characteristics of providers as well as mechanisms that lie outside of the care setting. Characteristics of providers serving socially at-risk populations that may drive differences in quality and outcomes include having fewer financial resources (e.g., lower margins, historically lower reimbursement rates) and having fewer and lower-quality clinical/health care resources (e.g., fewer technological resources and lower information technology capacity, fewer and less qualified clinicians) (Appari et al., 2014;

Bach et al., 2004; Blustein et al., 2010; Frimpong et al., 2013; Groeneveld et al., 2005; Jha et al., 2007, 2008; Li et al., 2015). Mechanisms driving disparities in health care outcomes that lie outside of provider settings include barriers to access and financial constraints for disadvantaged persons and differences in case-mix, including patient clinical characteristics and social risk factors (Chien et al., 2007; Jha and Zaslavsky, 2014; Karve et al., 2008; NASEM, 2016). For example, patients who cannot afford co-payments for prescription drugs or office visits may be less likely to keep chronic conditions under control.

Additional systemic factors driving differences between providers that may also be associated with quality of care and in turn health care outcomes include patient preferences for culturally concordant clinicians and the context of a patient’s place of residence such as racial segregation and neighborhood disadvantage (Bach et al., 2004; Dimick et al., 2013; Popescu et al., 2010; Sarrazin et al., 2009). For example, Dimick and colleagues (2013) found that black patients who lived in the most racially segregated areas were more likely than white patients to undergo surgery at low-quality hospitals even though black patients were also more likely on average than white patients to live nearer to higher-quality hospitals. While these different drivers of disparities in health care quality and outcomes can be understood theoretically as static processes, in actuality, they occur in a more dynamic process such that mechanisms at the individual level (e.g., in the patient–provider encounter), health system level (e.g., provider characteristics), and community level (e.g., social risk factors) occur simultaneously and also interact (Gehlert et al., 2008).

The complex, interacting nature of the drivers of variation in the quality of care and health care outcomes makes it difficult to draw clear conclusions about what precisely drives this variation among providers that disproportionately serve socially at-risk populations. Combined with the fact that, as described in the previous section, the committee was unable to identify high- or low-performing providers if interpreted as universally high or low performers across all outcomes, it follows that it is also problematic to then identify practices associated with the performance of universally high- and low-performing providers, let alone among those disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations, and to make comparisons between them. This is consistent with a study of top-performing hospitals in AMI mortality rates, which found that although all hospitals identified precise protocols and practices targeted at reducing mortality among patients with AMI, the authors identified no single shared practice or set of practices that was instrumental or essential to reducing AMI mortality (Curry et al., 2011). Nevertheless, recognizing that some providers have achieved high performance for certain conditions or in certain quality domains, the committee turned to case studies to identify specific practices used either to improve performance or achieve high performance for socially at-risk populations or to mitigate the effects of social risk factors on their patient population’s health outcomes within specific facilities. The committee reviewed both the peer-reviewed and grey literature in order to identify innovations, interventions, and other strategies providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations have implemented to improve care and outcomes for their patients. As described in Chapter 1, the committee reached out to organizations known to conduct research or represent providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations (Alliance of Community Health Plans, America’s Essential Hospitals, America’s Health Insurance Plans, and The Commonwealth Fund) and asked for help identifying relevant case studies, especially those that are not within the peer-reviewed published literature.

The committee reviewed the 60 case studies submitted, as well as the published literature. The case studies and published literature include strategies implemented to improve care and outcomes for socially at-risk populations from a variety of providers, not only those providers disproportionately serving socially at-risk populations. The evidence identified through these searches has substantial limitations. The literature revealed few rigorous (controlled) evaluations, which precluded inferences about causal effects of specific strategies. Moreover, because the case studies describe interventions tailored to a local community context, they are unlikely to be generalizable to providers with different resources and located in different communities. In addition, although the case studies documented concerted efforts to improve care processes and patient outcomes, outcome data were limited and the relative performance of individual providers compared to their peers was not well documented. Given these limitations, the committee was not able to identify “best practices” if interpreted as uniform and universal strategies to provide high-quality care for socially at-risk populations and was not able to make comparisons between high- and low-performing providers, even among case studies. Furthermore, because community context is a central determinant of what is needed, acceptable, and feasible in different configurations of problems and resources, universal and uniform implementation of “best practices” to improve care for all patients within a population and in all settings may not be desirable. As described above, this is consistent with the quality improvement literature. For example a study of top-performing hospitals in AMI mortality rates reported that no single practice or set of practices was essential to achieving high performance (Curry et al., 2011), and leadership and frontline personnel from eight minority-serving institutions identified customizing their approach (compared to using commercially available guides or toolkits) as key to reducing readmissions (Joynt et al., 2014). Likewise, a study identifying best practices for implementing disparities reduction initiatives based on findings from a series of systematic reviews reported that successful interventions “must be individualized to specific contexts, patient populations, and organizational settings” (Chin et al., 2012, pp. 994–995). Nevertheless, as will be described in a subsequent section:

The committee found examples of specific strategies implemented in specific community contexts by providers serving socially at-risk populations with the goal to improve health care quality and health outcomes.

IDENTIFYING SYSTEMS PRACTICES

Committee members identified commonalities from the review of the case studies, informed also by the literature and, in some cases, members’ empirical research or professional experience delivering care to socially at-risk populations. The common themes describe a set of practices delivered within a system of collaborating partners, not to specific health care interventions, and are consonant with research findings from the quality improvement literature and related clinical interventions designed to decrease disparities. Note that “system” as used here is not limited to a single health care organization, but refers more generally to a set of interconnected actors who work together to accomplish a common purpose—in this case to improve health equity and outcomes for socially at-risk populations. In this approach, the system is mainly composed of medical providers as well as partnering social service agencies, public health agencies, community organizations, and the community in which those medical providers are embedded. The medical providers may be formally (i.e., through legal arrangements) or

informally related to the external partners, but all serve the same community or geographic region.

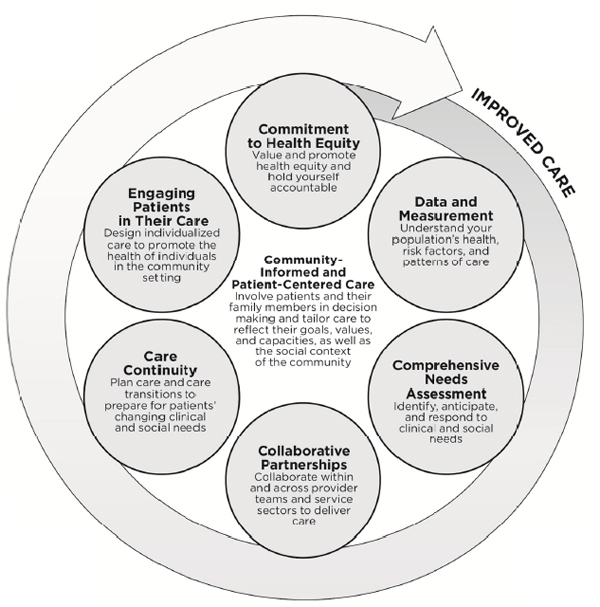

The committee concluded that six community-informed and patient-centered systems practices show promise for improving care for socially at-risk populations:

- Commitment to health equity: Value and promote health equity and hold yourself accountable.

- Data and measurement: Understand your population’s health, risk factors, and patterns of care.

- Comprehensive needs assessment: Identify, anticipate, and respond to clinical and social needs.

- Collaborative partnerships: Collaborate within and across provider teams and service sectors to deliver care.

- Care continuity: Plan care and care transitions to prepare for patients’ changing clinical and social needs.

- Engaging patients in their care: Design individualized care to promote the health of individuals in the community setting.

In the next section, the committee describes the case studies, as well as supporting literature from the quality improvement and disparities-reduction literature, that support the systems practices. It is important to note that these practices together constitute a general approach to identifying and developing best practices for a specific community context and given specific resources. Unlike clinical best practices that are applied to all individuals in a given population and that are derived from systematic reviews of the evidence to identify causal associations, these systems practices are not interventions that can be applied wholesale in every practice setting for every patient and in every community context and be expected to improve quality and outcomes for socially at-risk populations. Rather, a health care system can use these systems practices to conduct routine self-assessments to identify areas to improve care for socially at-risk populations and develop improvement strategies tailored to the system’s specific assets, barriers, needs, and capacities. These practices pertain to all health systems that serve socially at-risk populations.

As shown in Figure 2-1, the committee conceives of this system as grounded in community-informed and patient-centered care and emerging out of a commitment to health equity. This commitment supports and drives the other population-based practices, resulting in individualized care that promotes the health of the patient in his or her community context. Although in reality, a provider simultaneously engages in each system practice, each practice captures a thought process and set of decisions that logically influence the next. For example, a system may already conduct a comprehensive needs assessment, but this assessment will be fundamentally different when driven by a commitment to health equity and when it includes social needs in addition to clinical needs. The value and resources that flow from this commitment drive changes in other processes, such as collaborating with social service agencies in the community, which support enhanced planning for care transitions. Finally, the hard work of providing high-quality care is never done; this systems approach provides a continuous process for improvement.

While these systems practices build on existing models of health care quality improvement, care coordination, care transitions, and patient-centered care, this aspirational and innovative model differs from existing models because it focuses on achieving health equity, incorporates how health systems may address social risk factors, and expands on patient-centered care models to include the broader communities in which patients and health systems are embedded. While other models of care include team-based care (e.g., patient-centered medical home, chronic care model, transitional care and care transitions models) (Coleman et al., 2006; Davis et al., 2005; Naylor et al., 2004; Wagner et al., 1996), these are typically limited to clinical teams, whereas this model also incorporates collaborative partnerships with external organizations, including not only other clinical care providers, but also community organizations and social service and public health agencies to address social risk factors. In sum, these practices make up an approach by which health care systems can promote equitable health outcomes by using data to reveal unmet needs, which are then addressed through collaborative partnerships that coordinate care across time, sites of care, and intensity of needed services to

support patients living in the community to engage in their health care in the context of patient goals and community resources.

Tables 2-1a through 2-1f provide summary descriptions of the six systems practices, example implementation strategies, and considerations for implementation. The individual systems practices are discussed in more detail along with case studies that illustrate how these systems practices have been implemented in specific community contexts in the following sections. The case studies highlighted were selected for the comprehensiveness of their descriptions. As such, they are not a representative sample of strategies used by providers and are inherently interventions tailored to meet the needs of specific populations in specific community contexts. Additionally, particular strategies and their affect on improving health care quality and health outcomes may not be replicable by different providers and in different settings. Furthermore, the case studies date back several years and the practices described may no longer be present in the organization. The intervention strategies provide examples of the types of strategies organizations have used to apply a given systems practice in their organizational setting for specific patient populations and given their specific community context. Appendix A provides examples of implementation strategies and examples of case studies in which these strategies were identified.

TABLE 2-1a Description of Systems Practices to Improve Care for Socially At-Risk Populations and Implementation Considerations: Commitment to Health Equity

| Systems Practice | Description | Example Implementation Strategies | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commitment to health equity: Value and promote health equity and hold yourself accountable | Health care leaders and staff at all levels express a core commitment to valuing and promoting health equity. Health care providers accept accountability for reducing inequities. Strategic decision making considers the impact on equity and has the goal of producing equity as an outcome of the organization’s operations. |

|

Achieving health equity is also interdependent with other goals to achieve a high-performing health system, including redesigning care delivery and aligning financial incentives. Embedding equity as a value in a health system requires leadership and a change in organizational culture. Leadership sets expectations for staff at all levels regarding activities related to equity and provides feedback on achievement. Valuing equity is a practice that permeates each of the other systems practices. |

SOURCES:

a Chin et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2015.

e IOM, 2001.

f Chin et al., 2012; IOM, 2001; Weech-Maldonado et al., 2012.

h Ayanian and Williams 2007; Chin et al. 2012; Jones et al. 2010.

i Chien et al., 2007; Davis et al., 2015; Peek et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2015.

j Personal communication, Susan Knudson (HealthPartners) to Chuck Baumgart (committee member), December 14, 2015.

k Chin, 2016; Chin et al., 2012; Curry et al., 2011; Davis et al., 2015; IOM, 2003; Jones et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2015.

TABLE 2-1b Description of Systems Practices to Improve Care for Socially At-Risk Populations and Implementation Considerations: Data and Measurement

| Systems Practice | Description | Example Implementation Strategies | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data and measurement: Understand your population’s health, risk factors, and patterns of care | Health care providers understand their patterns of performance across different indicators of social risk. Providers know how their performance for socially at-risk populations compares with top-performing peers. | The concentration of socially at-risk patients among a small subset of health care providers means that many providers will be unable to reliably assess disparities with internal data alone. Providers may need to benchmark their performance against peer organizations or population-based measures. |

SOURCES:

a Ayanian and Williams, 2007; Chin et al., 2012; HHS, 2011a; IOM, 2003, 2009; Thorlby et al., 2011.

b Ayanian and Williams, 2007; Chin et al., 2012; HHS, 2011a; Sequist et al., 2008; Thorlby et al., 2011.

c For example, Hostetter and Klein, 2015; Johnson et al., 2015.

TABLE 2-1c Description of Systems Practices to Improve Care for Socially At-Risk Populations and Implementation Considerations: Comprehensive Needs Assessment

| Systems Practice | Description | Example Implementation Strategies | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive needs assessment: Identify, anticipate, and respond to clinical and social needs | Providers analyze performance data, as well as directly engage patients, to identify unmet clinical or social needs. Providers also review the literature and the experiences of peers to identify lessons and anticipate their patient population’s needs. Based on these activities, providers design programs and practices that anticipate and respond to those needs. |

|

Different causal mechanisms may predominate in different contexts. It may be difficult to replicate others’ program results when important contextual features differ. |

SOURCES:

a For example, ACHP, n.d.-c.

b Personal communication, Doug McCarthy (The Commonwealth Fund) to staff, January 12, 2016.

TABLE 2-1d Description of Systems Practices to Improve Care for Socially At-Risk Populations and Implementation Considerations: Collaborative Partnerships

| Systems Practice | Description | Example Implementation Strategies | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative partnerships: Collaborate within and across provider teams and external partners to deliver integrated, coordinated care | Providers create collaborative teams to deliver services with scope, intensity, and scale matched to population needs. Collaborations will often need to span multiple service sectors, such as housing, transportation, and nutrition. Collaborations must be sufficiently integrated to share information and critical insights about patients. |

|

Key questions to identify care partners include Who has the resources and skills to help? What informal relationships can be used as building blocks to create collaborations? What are community partners already doing successfully that can be built on? Collaborations may evolve over time as needs and obstacles become clearer. In addition, effective models of collaboration will differ based on the specific patient needs and community context. |

SOURCES:

a Alley et al., 2016; Corrigan and Fisher, 2014; Fisher, 2008; Greenberg et al., 2014; Huang and Rosenthal, 2014.

b Chin et al., 2007, 2012; Davis et al., 2015; IOM, 2003, 2015d.

c Felland et al., 2013; IOM, 2003, 2015d.

d Cebul et al., 2015; McCarthy et al., 2014; Press et al., 2012.

e Davis et al., 2015; Peek et al., 2007; Sandberg et al., 2014; Schor et al., 2011.

TABLE 2-1e Description of Systems Practices to Improve Care for Socially At-Risk Populations and Implementation Considerations: Care Continuity

| Systems Practice | Description | Example Implementation Strategies | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Care continuity: Plan care and care transitions to prepare for patients’ changing clinical and social needs | Health care providers anticipate and carefully plan patient trajectories through illness progression, across sites of clinical care, between clinical care teams, between health care providers and social service agencies and community organizations, and differing intensity of needed services. Providers design transitions and hand-offs to maintain patient engagement and avoid losses to follow up. |

|

Programs must be prepared for cycles of patient progress and relapse. After successful intervention, providers may need to monitor patients to ensure that progress is maintained, as well as to detect relapse and re-intensify services as needed. |

SOURCES:

a Chin et al., 2012; Davis et al., 2015.

b Chin et al., 2007, 2012; Davis et al., 2015; Masi et al., 2007; Naylor et al., 2011; Peek et al., 2007; Van Voorhees et al., 2007.

c Hostetter and Klein, 2015; IOM, 2015d; Naylor et al., 2011.

d For example, Buchanan et al., 2009; Larimer et al., 2009; Martinez and Burt, 2006; Pirraglia et al., 2011.

TABLE 2-1f Description of Systems Practices to Improve Care for Socially At-Risk Populations and Implementation Considerations: Engaging Patients in Their Care

| Systems Practice | Description | Example Implementation Strategies | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engaging patients in their care: Design individualized care to promote the health of individuals in the community setting | Providers design care to promote functioning in the patient’s home and neighborhood or other chosen environment. For different patients, the same function (e.g., self-management support) could be realized through different forms (e.g., nurse care manager or community health worker) depending on the level of severity and desired site of care (office visits versus phone consultation versus home visits). |

|

Different solutions may be required in different contexts, because causal mechanisms differ or interact in varying ways. For instance, readmissions may be due to inadequate instrumental support (e.g., transportation), undiagnosed behavioral illness, or both. |

SOURCES:

a Itzkowitz et al., 2016; Naylor et al., 2012; Press et al., 2012; Sajid et al., 2012.

b Chin et al., 2012; Hemmige et al., 2012; Masi et al., 2007; Peek et al., 2007; Van Voorhees et al., 2007.

EVIDENCE BASE FOR THE SIX SYSTEMS PRACTICES

Providing community-informed and patient-centered care is a core principle underlying each of the six systems practices described in the following sections. Patient-centered care is a component of high-quality care, but it may be particularly salient to patients with social risk factors who may be at increased risk of receiving lower-quality care and having poorer care experiences (Crawford et al., 2002; IOM, 2001; NASEM, 2016). Patient-centered care reflects the patient’s goals and values (IOM, 2001, 2013a). This means that patients are involved in making decisions about their care and practitioners understand what is practical for the patient to do given the individual patient’s degree of agency and opportunity in daily life (Ferrer et al., 2014, 2016; Joynt et al., 2014). Additionally, providers reduce barriers to accessing care and coordinate care across care settings (and with external partners) (IOM, 2001, 2013a). Although patient-centered care shows promise to improve outcomes, especially with respect to patient experiences and self-management, there remains little evidence on effects on clinical outcomes, use, and costs—in part because it may take time for these benefits to accrue (Crawford et al., 2002; IOM, 2013a; Jackson et al., 2013; Jaen et al., 2010; Rathert et al., 2013).

Community-informed care expands on the principle of patient-centered care to also understand and account for the community context in which a care setting and a patient are embedded. As described in the committee’s first report (NASEM, 2016), community context refers to a set of broadly defined characteristics of residential environments, including physical and social environments, policies, infrastructural resources, and opportunity structures that may be relevant to health and health care outcomes. Because communities can be defined along multiple axes (e.g., geographically defined communities, racial or ethnic communities, and other social groups), health systems may serve multiple, potentially overlapping communities. Communities will vary in the ways they frame issues, the language used to discuss them, and cultural meanings attached to interventions (Hawe et al., 2009). Practicing community-informed care means that health care providers design care with an understanding of the local community’s orientation to different needs and proposed interventions. Providers also design care with a deep understanding of the community environment, including assets, obstacles, key partners, and cultural considerations. The committee chose the term community-informed to connote care that takes account of assets, conditions, and needs in the community where the patient resides, and is agnostic about whether care is “based” in the community.

Practicing community-informed care will require not only recognition of what community needs exist, but also that communities will have different types of needs, which can be met in different ways. In applying each of the systems practices, health care organizations may provide clinical interventions tailored to populations based on social context. Additionally, health care organizations may partner or establish coalitions with social service and public health agencies and community organizations. This may be particularly relevant for organizations with more limited resources. Health care organizations may also intervene directly on social issues—for example, providing supportive housing or opportunities for socialization. Finally, health care organizations may identify social risk factors that the medical or clinical health system cannot address or should not address. For certain social risk factors, presuming that primary solutions lie within the health care sector risks “medicalizing” the factors in undesirable ways if the health care sector acts on them, because they may be better addressed through social policies or interventions rather than through individual medical interventions (Lantz et al., 2007; Woolf and

Braveman, 2011). For example, although patients may have health or social issues related to low educational attainment, these problems may be better addressed through interventions in the education sector than through health care interventions. Identifying how and why a community can or should be engaged will likely be essential to effective community engagement (HHS, 2011b).

Community involvement occurs along a continuum that ranges from simple outreach to a strong, bidirectional relationship with shared leadership (HHS, 2011b). Specific ways in which health care providers can better understand the community they serve and address a community’s needs include soliciting information, guidance, and feedback on program designs, identifying and partnering with community resources, having a significant organizational presence, and investing in the community (e.g., HHS, 2011b; Meyers, 2008). Community-informed health care providers may simply seek input or feedback from community stakeholders about program design. Community-informed health care providers may also seek to know of and align their programs with existing community efforts, such as maintaining a repository of available community-based resources with which the health care provider can partner or to which a provider can refer patients for services (e.g., Joynt et al., 2014; Klein and McCarthy, 2010). Health care providers can also work with existing community assets to collaboratively reach out to socially at-risk populations. Hospitals can provide community-level population health data to facilitate collaborations with the community. Having a significant presence in the community can include having visible, community-based office locations and having staff who reside in and are hired from the community. Investing in the community could include expressing an organizational commitment to support unmet community needs, such as engaging in community service activities in the community or providing charitable care, as well as directly investing in the community, such as hiring staff from the community, providing health-promoting resources such as establishing farmers’ markets in the community, and identifying funding strategies to address population health across health care and social services (Halfon et al., 2014; Meyers, 2008). These varying levels and ways of involving communities are discussed in more detail throughout the next sections on the six systems practices.

Kaiser Permanente is a large, nonprofit integrated managed care organization that provides a case study of a community-informed health system. Kaiser’s comprehensive, multifaceted approach to improving community-level health uses ethnography and interviewing to understand drivers of health disparities; reduces barriers to receiving coordinated, culturally, and linguistically appropriate clinical care; promotes healthy behaviors in the community through targeted dissemination and interventions (e.g., farmers’ markets, partnering with community activists to promote healthy eating and physical activity); and invests in environments supportive of health (Kaiser Permanente, n.d.; Meyers, 2008; Tyson, 2015). Health Share of Oregon’s Community Advisory Council provides an example of a more structured approach to providing community-informed care, and is described in Box 2-1.

Commitment to Health Equity

As described in Chapter 1, health equity means that every person has the opportunity to attain his or her full health potential and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or other socially determined circumstances. Conversely, health inequities refer to unfair differences or inequalities in health, and focus on systematic, often social processes that drive these inequalities, such as the distribution of resources (CDC, 2015). The Institute of Medicine (IOM) previously identified equity as fundamental to high-quality health care (IOM, 2001). The IOM also identified health care organizations together with individual clinicians, patients, and their legal and regulatory contexts as being responsible for eliminating health care disparities (IOM, 2003). However, achieving health equity requires more than providing equitable health care, or the same type of care to all patients regardless of social risk, because this may not be sufficient to reduce health inequities. Indeed, some subpopulations may need more intensive care to achieve the same health outcomes.

Providing high-quality health care for socially at-risk populations may require organizations to embed health equity as a value through organizational commitment and leadership. Embedding health equity as a value of an organization’s culture will likely require commitment from staff in all areas and at all levels of an organization, especially senior leadership. For example, studies of interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities identified top-down commitment from leadership to reducing disparities in health care as essential to effective interventions (Chin et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2010). Similarly, studies of top-performing hospitals, including a systematic review, identified leadership commitment to and involvement in quality improvement as key to achieving high performance (Curry et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2015). Another study of organizational changes to improve the quality of care in safety-net

systems identified organization-wide commitment and support for practice redesigns, including support from leadership, as important to effective practice transformation (VanDeusen-Lukas et al., 2015).

To demonstrate their commitment to equity, organizational leaders, including executives and governance, may need to identify reducing health inequities as an organizational priority, such as by incorporating equity as a value into the organization’s vision, mission, and goals. For example, one study identified incorporating practice redesigns into an organization’s vision, mission, and values as an organizational change important for improving the quality of care in safety-net settings (VanDeusen-Lukas et al., 2015). Organizational leaders can also show their commitment to equity by allocating financial and non-financial resources (including workforce and technology investments discussed below) to achieve equity goals. Studies of high-performing hospitals, including a systematic review, found that providing financial and non-financial resources were critical to improving quality (Curry et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2015). Literature also suggests that achieving health equity is a goal interdependent with other goals to provide high-performing health care, such as redesigning care delivery to provide high-quality care, improving health outcomes and patient experience, and reducing health care costs (American Medical Group Association, 2011; Berwick et al., 2008; Chin et al., 2012; IOM, 2001, 2010). Organizational leaders can further support equity goals by supporting practices targeted at reducing health disparities, incorporating the goal of promoting equity into organizational policies and processes (including quality improvement processes), and by holding staff accountable (Curry et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2015). Specific activities into which leaders can incorporate the aim of achieving health equity to support organizational transformation to achieve a culture of equity may include

- Investing in a diverse workforce to provide culturally concordant and culturally competent care and improved communication;

- Designing interventions to reduce health disparities

- Redesigning care to incorporate equity goals; and

- Setting measurable goals to reduce health disparities and holding staff accountable

Workforce Investments to Promote Health Equity

Initiatives targeted at enhancing workforce capacity to reduce health inequities include investments in additional staff such as hiring language interpreters or clinical and non-clinical staff from diverse backgrounds as well as staff development activities such as providing education, trainings, and other resources for staff (IOM, 2003). Evidence from the quality improvement literature shows that building and maintaining highly qualified staff, recruiting staff who are committed to the organizational vision, and developing talent through mandatory and specialized trainings (such as on evidence-based practice) is important to achieving high performance in hospitals (Taylor et al., 2015). Trainings regarding health equity may address cultural competence to improve communication between patients and providers, social determinants of health to increase awareness of social risk factors and capacity to identify potential unmet social needs, best practices for engaging with language interpreters, and social justice issues such as unconscious bias (American Medical Group Association, 2011). Although evidence is limited (Anderson et al., 2003; Meghani et al., 2009), some evidence suggests that racial concordance between physicians and patients may be associated with better quality of care

and increased patient trust, satisfaction, and intent to adhere (Cooper and Powe, 2004; Street et al., 2008). Similarly, a systematic review found that studies of cultural competency training for health professionals reported no effect to moderately beneficial effects on patient outcomes and no negative effects (Lie et al., 2011). Another more recent study found that hospitals with greater cultural competency (covering commitment from leadership, integration of cultural competency into management and operations, workforce diversity and training, community engagement, patient–provider communication, and care delivery supportive of culturally competent practice) were associated with better patient experiences of care overall and better scores for nurse communication, staff responsiveness, quiet room, and pain control among racial and ethnic minorities (Weech-Maldonado et al., 2012).

Designing Interventions to Reduce Health Inequity

To achieve health equity, health care organizations may need to proactively design interventions to reduce disparities, such as by improving care for certain targeted subpopulations. As described above, providing the same type of care to all patients may not reduce disparities. For example, socially at-risk populations may require more intensive care. A study identifying themes from systematic reviews of interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities found that successful interventions involved the active design of interventions to reduce disparities that were targeted to specific contexts, patient populations, and organizational settings (Chin et al., 2012). This may include designating internal leaders across the organization who are responsible for developing and overseeing a strategic plan to monitor and reduce health disparities. For example, a study of characteristics common to successful practice transformation to improve quality in safety-net systems noted that physician leaders and operational leaders must be engaged to spearhead practice transformations (VanDeusen-Lukas et al., 2015). Similarly, identifying a quality improvement “champion” and creating a quality improvement team comprising staff from all levels was common to successful interventions to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities (Chin et al., 2012). Based on these systematic reviews, the study also identified appointing staff to disparities-reduction initiatives as a best practice for implementing interventions to reduce disparities (Chin et al., 2012).

Redesigning Care to Promote Health Equity

An organization that is committed to achieving equity may need to not only design interventions to reduce health inequities, but also incorporate equity goals into its general organizational practices and procedures. As described above and in the experience of HealthPartners of Minnesota (American Medical Group Association, 2011; see also Box 2-2), incorporating the aim of equitable care in resource allocation, overall strategic planning and individual practices, and accountability processes such as performance reporting are essential to transforming an organizational culture to one that promotes health equity and reduces health disparities (Berwick et al., 2008; Chin et al., 2012; IOM, 2001, 2010). An organization’s strategic plan provides a way to translate the aim of achieving equity in all organizational practices into an actionable strategy in which each practice incorporates the aim of achieving equity (American Medical Group Association, 2011; VanDeusen-Lukas et al., 2015). A study synthesizing lessons from successful interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities based on a series of systematic reviews noted that effective interventions must be integrated with overall quality improvement efforts, rather than be a separate, discrete initiative (Chin et al.,

2012). Thus, valuing equity is a practice that will permeate each of the other systems practices to improve care for socially at-risk populations.

Specific practices to support equity goals include investments in health information technology (HIT) and redesigning care to promote equity. Technology should facilitate identifying socially at-risk patients and populations, as well as their clinical and social needs and assets. HIT investments should also facilitate the provision of data in ways that are easily understood by all levels of staff, including community-level population health data for senior managers and clinic-level data for frontline staff. Here, the population in “population health” refers to all people residing in the provider’s catchment area, or the geographic community it serves, and is not restricted to an enrollee or patient population. These activities are discussed in

more detail in subsequent sections on data and measurement and comprehensive needs assessment. Care should be redesigned to provide integrated, accessible, coordinated, team-based care that links clinical and social interventions to reduce barriers to care and to support the health of patients in the community setting. Although these are acknowledged as good practice for the general population (IOM, 2001, 2013a), they may be especially relevant for socially at-risk populations that have more unhealthy behaviors, more numerous and more complex health needs, more difficulty managing their health and social needs, and more limited health literacy; experience greater barriers to accessing care; may be at increased risk of receiving lower-quality care and having poorer care experiences; and who potentially receive care from multiple providers across a broad range of services (Bachrach et al., 2014; Crawford et al., 2002; Davis et al., 2015; IOM, 2001, 2013a; NASEM, 2016; Schor et al., 2011). Organizations that value equity should pay particular attention to ensure that the design of their care facilitates providing equitable care and promotes equitable health care outcomes.

Because a commitment to health equity acknowledges that social processes drive inequalities in health, to reduce health inequities and improve care for socially at-risk populations, organizations may be motivated to acknowledge the social context of their patient populations and even address social risk factors for poor health outcomes (Bachrach et al., 2014). This may be particularly true in the context of value-based purchasing models that provide economic incentives to do so (Bachrach et al., 2014). To consider and address social risk factors for poor health care outcomes, organizations may need to go beyond providing equitable care within the walls of their health systems to understand, partner with, and in some cases invest in the community in which they are embedded to support health outcomes of the communities they serve (Bachrach et al., 2014; Chin et al., 2012; Schor et al., 2011). Specific practices to redesign care for socially at-risk populations are discussed in more detail in subsequent sections on collaborative partnerships, care continuity, and engaging patients in their care.

Accountability for Health Equity

Effectively reducing health inequities will likely require an organization to accept accountability for its population health outcomes. Because population health is defined at the community level and is not restricted to an enrolled or patient population, organizations are accountable for community-level population health outcomes, not just the outcomes of their patient population. Accountability consists of both internal accountability within the health system and external accountability, such as accountability to third-party payers like Medicare. Accountability within the health system means that everyone within an organization from executive leadership down to frontline staff is accountable for population health outcomes. This requires organizations to acknowledge health disparities between subpopulations, set measurable goals to reduce disparities identified, and ensure these goals are achieved equitably (Ayanian and Williams, 2007).

Organizational leaders can set equity goals by communicating equity as part of their organizational vision, mission, and goals to staff at all levels through orientations and trainings and setting expectations regarding activities and practices staff should perform to reduce disparities. For example, a study identifying best practices for implementing interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities based on common themes identified through systematic reviews of such interventions suggests that organizations can make staff understand their role in reducing disparities by incorporating disparities-reduction training into staff orientations and including responsibilities with respect to disparities reduction into job descriptions (Chin et al.,

2012). Organizational leaders can then ensure that equity goals are met through performance monitoring and reporting and hold staff accountable by evaluating and providing feedback to staff on their achievement on activities related to equity. Studies of interventions to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities found that simply having and providing data on disparities increased awareness about disparities but was not associated with improved outcomes (Sequist et al., 2010; Thorlby et al., 2011). However, a systematic review of interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes found that providing in-person feedback to providers about their performance improved diabetes outcomes for African-American patients (Peek et al., 2007). Similarly, one study found that providing feedback to providers improved care for high-cost Medicare beneficiaries (Davis et al., 2015) and a systematic review of high-performing hospitals identified feedback to address low performance as well as rewarding and recognizing high performance as important to achieving high performance overall (Taylor et al., 2015). In some cases, it may also be appropriate to incorporate disparities-reduction goals into payment incentives and other compensation for management and physicians.1 External accountability can further support the alignment of interdependent goals to also incentivize health equity improvements (Jones et al., 2010).

HealthPartners of Minnesota and Kaiser Permanente provide two case studies of embedding equity as a value in a health system. HealthPartners is a Minnesota-based integrated health care organization that integrated the aim of equitable care into a larger practice transformation and successfully reduced disparities in cancer screenings, heart failure care, and diabetes outcomes2 (American Medical Group Association, 2011). This initiative is described in Box 2-2. Kaiser Permanente (also described in the previous section) made an organizational commitment to reducing health disparities beyond providing equitable health care (Meyers, 2008; Tyson, 2015). Specific initiatives Kaiser Permanente implemented include investing in local communities, Kaiser’s Community Health Initiatives program, and reducing the environmental impact of its facilities (Meyers, 2008). One way in which Kaiser invests in the communities it serves is by partnering with local health departments and public hospitals to invest in HIT and provide technical assistance for implementing quality improvement initiatives in safety-net settings. The Community Health Initiatives program supports increasing food access, such as establishing weekly farmers’ markets at its hospitals and medical office buildings to improve access to healthy foods, and promoting healthy environments, such as supporting health promotion programs in the workplace (Kaiser Permanente, 2015). Efforts to build healthier facilities include infrastructure investments to use more environmentally friendly construction and design elements and minimize the environmental impact of its processes on the local communities. For example, Kaiser replaced the use of regular diesel fuel with more environmentally friendly biodiesel fuel for its supply transportation and courier trucks to reduce harmful emissions and air pollution in its local communities (Meyers, 2008).

Data and Measurement

Measurement is fundamental to quality improvement in health care (Berwick et al., 2008). Health care providers that aim to improve care for their socially at-risk patients maintain not only performance data but also data on the distribution of performance by various indicators

__________________

of social risk. Studies have found that regularly collecting consistent race, ethnicity, and language data among a provider’s patient population and analyzing performance data disaggregated by race, ethnicity, and language to identify existing health disparities within their organizations are critical to effective interventions to reduce disparities (Ayanian and Williams, 2007; Chin et al., 2012; CMS, 2015; HHS, 2011a; Jones et al., 2010; Thorlby et al., 2011). Similarly, a systematic review of high-performing hospitals found that performance monitoring and reporting is essential to improving overall quality of care (Taylor et al., 2015). Together, this literature suggests that collecting consistent data by social risk factors and disaggregating data by indicators of social risk may also be critical for improving care for socially at-risk populations. Although there is little evidence to date that simply collecting and reporting data effectively improves care and reduces disparities, some studies have shown that providing performance data stratified by race and ethnicity increased awareness about disparities; these studies suggest that those who identify disparities may be motivated to seek to understand the drivers of and to reduce disparities (Chin et al., 2012; RWJF, 2011; Sequist et al., 2010).

Because socially at-risk populations are disproportionately represented in a small subset of providers, internal performance data may not be sufficient to reveal health disparities. Health care providers may also need to routinely compare their performance to those of peer organizations and top performers and consider examining community-level health data, such as those identified in coordination with local public health agencies, in addition to population health data on their patients. Early adopters of race and ethnicity data collection and stratified reporting identified a lack of standardized data as a primary challenge to comparing performance to peer organizations (RWJF, 2011; Thorlby et al., 2011). In previous reports, the IOM recommended core metrics for health and health care (IOM, 2015d), population health measures (IOM, 2013b), standardized data on race, ethnicity, and language (IOM, 2009), and social and behavioral domains and measures that may capture additional social risk factors for poor health (IOM, 2015a).

Furthermore, as described in the earlier section on publicly reported performance data, because there is little consistency in top performers across measures, domains, and time (e.g., (Gaskin et al., 2011; Girotra et al., 2012; Jha et al., 2005, 2008; McHugh et al., 2014; Shwartz et al., 2011), it will be important to identify appropriate peers for comparison. Maintaining accurate and complete data may also facilitate the identification of clinical, behavioral, and social needs within a provider’s patient population. Comprehensive needs assessment is discussed in the next section.

Montefiore Health System and Denver Health provide case studies of two safety-net systems that developed analytic tools to better identify socially at-risk patients. Montefiore Health System, a safety-net provider located in the Bronx in New York City, internally developed the Clinical Looking Glass, a data analytics tool to identify and reach out to patients whose conditions are not under control and who have missed follow-up appointments (Hostetter and Klein, 2015). Denver Health, the largest public safety-net provider in Colorado, developed an analytic tool that enhances standard clinical predictive models using a set of rules to segment its patient population into risk tiers matched to clinical and social services and staffing models (Hostetter and Klein, 2015; Johnson et al., 2015). This tool is described in more detail in Box 2-3.

Comprehensive Needs Assessment

Health care providers that seek to improve care for socially at-risk populations periodically may need to conduct comprehensive needs assessments to proactively identify patients at risk. Anticipating patient needs is fundamental to improving care for all patients (IOM, 2001). However, socially at-risk populations are likely to have unmet social needs that affect health care outcomes (NASEM, 2016) that may not be identified through clinical data alone. Thus, comprehensive needs assessments may need to include not only consideration of clinical and behavioral risk factors as is done for the general population, but also social risks that may be related to health care outcomes. As such, comprehensive needs assessments may use clinical risk prediction models, but may also require further analysis of performance and other data (for example, patient-generated data, clinical notes, or physician observations) to identify unmet needs. In addition to needs or deficits, providers should also identify strengths and capacities of patients and communities that can be built on or enhanced (Green and Haines, 2016). Identifying and building on community assets and capacities may be important for sustaining community engagement (HHS, 2011b). Kaiser Permanente’s Colorado region developed a proactive health assessment tool described in Box 2-4 that provides a case study in proactively identifying health risks among Medicare beneficiaries (Kaiser Permanente Colorado, 2014). Among other results, an evaluation of the program found that beneficiaries and their

physicians reported that the tool helped raise potential health risks that otherwise would not have been raised during office visits and that diagnosis and treatment of depression among older beneficiaries increased (ACHP, n.d.-c; Groshek, 2015; Kaiser Permanente Colorado, 2014). In addition to analyzing internal data, health care providers may also review the literature and the experiences of peers to anticipate potential needs and assets in their patient population. However, needs and assets are specific to a particular community context and programs designed for other settings and their results may not be generalizable. Additionally, health care providers can also conduct needs assessments collaboratively with stakeholders from the community, such as local health and public health departments and community organizations. For example, under the Affordable Care Act, nonprofit (tax-exempt) hospitals must conduct a community health needs assessment every 3 years. Recommendations for conducting these assessments suggest that important components include defining the community; building shared ownership of community health and shared commitment to improving community health; data collection using shared measurement; data analysis, including stratified reporting by indicators of social risk, identification of assets, capacities, and unmet needs; defining priorities and a plan to address unmet needs; and engaging the community through continuous communication throughout all stages of the needs assessment and dissemination of results (Barnett, 2011; CDC, 2013; CHA, 2013; Myers and Stoto, 2006; Rosenbaum, 2013).

As implied by these components, results from the needs assessment can help providers to identify the scope, intensity, and scale of needed services. Health care providers may also use the results of these needs assessment activities to prioritize which needs the provider can best meet by balancing factors such as patient priorities based on intensity of need, whether the need is amenable to help from clinical or social interventions, and the health care provider’s own capacity to address a need. Finally, once unmet and potential needs have been identified (and prioritized), health care providers may need to design or identify programs and an implementation strategy to respond to these needs. Examples of practice transformation and other programs are described in the following section on collaborative partnerships.

Collaborative Partnerships

Improving health and health care outcomes for socially at-risk populations will require collaboration within and between care teams within health systems, across clinical settings, and between health systems and external partners, such as community organizations and public health and social service agencies (Bachrach et al., 2014; Schor et al., 2011). While this is also true of improving care for the general population, collaborative partnerships both within and beyond the clinical care setting may be particularly relevant for socially at-risk populations that are likely to have both medically complex conditions and unmet social needs (Bachrach et al., 2014; Schor et al., 2011). Collaboration within health systems internally include practice redesigns to provide integrated, accessible, coordinated care, such as through implementation of a patient-centered medical home (Sandberg et al., 2014; VanDeusen-Lukas et al., 2015; Wagner et al., 2014). Studies, including two systematic reviews, found that implementing a patient-centered medical home shows promise to improve quality of care and patient experiences, while less is known about the effect of implementing a medical home on clinical outcomes, utilization, and costs (Jackson et al., 2013; Jaen et al., 2010; Rathert et al., 2013). However, evidence from implementing the Chronic Care Model and other integrated care delivery models show the potential of such integrated models to improve both quality of care and clinical outcomes (Coleman et al., 2009; Davis et al., 2015). Although much of the evidence on medical homes comes from the general population or patients with chronic illnesses, some safety-net organizations have successfully transformed their practice into medical homes (Wagner et al., 2014).

With respect to specific elements of clinical practice designs that may improve care for socially at-risk populations, strategies to increase access to care that show promise for improving quality of care and patient outcomes include providing same-day appointments; extending practice hours in ambulatory care; using clinical staff such as paramedics and medical assistants and trained, unlicensed lay persons like community health workers and informal caregivers to support care management; and delivering care through new technologies such as mobile screening units and video and telephone consultations that bring clinical care to patients (Felland et al., 2013; IOM, 2015c; McCarthy and Mueller, 2008; Sandberg et al., 2014). Studies have also

reported that multidisciplinary teams have been important to improving care for high-cost Medicare beneficiaries (Davis et al., 2015) and reducing disparities (Chin et al., 2007, 2012; Peek et al., 2007). Furthermore, involving non-physician clinicians in care teams may improve care and reduce disparities. For example, a systematic review of interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes found that nurse- and pharmacist-led interventions showed promise to improve quality of care and health outcomes and potential to reduce disparities (Peek et al., 2007). Studies of high-performing hospitals also identified coordinated, patient-centered care teams and multidisciplinary and multi-level collaboration and communication as important factors for achieving high performance (Curry et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2015).

Whereas the medical home concept pertains principally to primary care settings, health systems may also redesign care across broader medical neighborhoods to coordinate and collaborate with other health care providers regionally (including specialists and hospitals) and in which performance measurement and payment systems are aligned to promote shared accountability for outcomes across the continuum of care (Fisher, 2008; Greenberg et al., 2014; Huang and Rosenthal, 2014; Silow-Carroll and Rodin, 2013; Van Citters et al., 2013). For example, a systematic review of high-performing hospitals identified collaboration and communication with other health services providers (including ambulatory care providers, administrators, and social services) throughout a patient’s care trajectory as a crucial improvement strategy (Taylor et al., 2015). Similarly, a systematic review of interventions to improve asthma outcomes among racial and ethnic minority adults found that Health Resources and Services Administration Health Disparities Collaboratives, established to bring together CHCs to share knowledge and disseminate quality improvement techniques, showed potential to improve quality of care (Press et al., 2012). An evaluation of MetroHealth Care Plus, a CMS waiver program comprising a regional health improvement collaborative of three safety-net organizations in Ohio that enrolled uninsured poor patients and accepted a CMS-approved budget-neutral cap, provides further evidence of the potential for collaborative partnerships to improve not only health care quality and outcomes, but also value. Program results reported improved diabetes outcomes among enrollees with diabetes and reduced hospitalizations among all enrollees (Cebul et al., 2015). Additionally, expenditures for enrollees averaged more than one quarter lower than the budget-neutral cap—$415.05 total per member-month costs for MetroHealth Care Plus compared to $582.41 for the budget-neutral cap or $104 million in actual services provided compared to the $145 million CMS-allowed expenditure cap for all eligible enrollees (Cebul et al., 2015).

Health care providers may also need to partner with community organizations and social service and public health agencies to link clinical interventions to social programs necessary to support healthy individuals, such as mental health services, substance abuse treatment, housing assistance, vocational counseling, legal assistance, and assistance with government benefits (Bachrach et al., 2014; Foubister, 2013; McCarthy and Cohen, 2013; Sandberg et al., 2014; Schor et al., 2011). For example, one study found that including and coordinating care among patients, family members, providers, and social service agencies showed “modest success” at improving care for high-cost, high-risk Medicare beneficiaries (Davis et al., 2015, p.e350). Case studies of three U.S. regions with relatively high performance despite greater poverty compared to other top-performing areas also identified collaboration across a wide variety of stakeholders (e.g., providers, patients, payers, nonprofit community organizations, academic researchers, faith-based groups, educators, etc.) as pivotal to achieving high performance (McCarthy et al., 2014). The case studies also identified shared commitment to increasing access to care for

underserved populations and regional cooperation to invest in and use health information technology as well as engage the community as important to increasing access to care for underserved populations and to achieve high performance overall (McCarthy et al., 2014).

As alluded to in these examples of regional collaboration, government can be an important facilitator of collaborative partnerships by providing leadership, aligning financial incentives (payment reform), promoting shared accountability (through both performance measurement/public reporting and financial accountability), and by facilitating enhanced funding for social risk factors related to health (e.g., through value-based purchasing methods, identifying and coordinating nonprofit community benefit funds, and by aligning non–health sector funding to promote population health) (Chin et al., 2012; Corrigan and Fisher, 2014; IOM, 2014, 2015b; Jones et al., 2010). For example, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene established the Citywide Colon Cancer Control Coalition that convened a wide range of stakeholders in 2003 to implement a multifaceted program, including an annual summit of stakeholders, a public education campaign, outreach and education to health care providers, patient navigator programs, and a quality improvement initiative to successfully increase colon cancer screening among all New York City residents age 50 and older and also to reduce racial and ethnic disparities (Itzkowitz et al., 2016).