5

Innovative Approaches to Measurement

Robert Gibbons (University of Chicago) discussed how computerized adaptive testing can be applied to mental health measurement. He reminded workshop participants of the discussion about the challenge in creating the K6 from 600 items. As part of that effort, six items were derived to produce a score for psychological distress. An alternative to administering the same set of six items to each individual would be to keep the “K600” and use computerized adaptive testing (CAT) to produce a score using a subset of the items, averaging six items—plus or minus two items—that are best suited for each person.

In classic measurement theory, using the K6 as an example, there are six items, measured on an ordinal Likert-type scale. These items are like a series of hurdles in a race and they are added to produce a score. The score is then supposed to be a sufficient statistic to represent something in the universe. If an additional item (another hurdle) is added (to produce a “K7” for example), or the distances between the hurdles are changed, the scores between the two tests are no longer comparable, so everyone is administered the same set of items. By contrast, item response theory (IRT) is more similar to a high jump, with the height of the bars measured in inches. More skilled jumpers could start higher and end up jumping higher than less skilled jumpers, but everyone is still measured using the same metric. IRT is a model-based measurement and enables adaptive testing, where one person can be administered one set of items, and

another person can be administered another set of items, while using the same metric.

Gibbons explained CAT with another metaphor. He asked the workshop participants to imagine a mathematics test that consists of 1,000 items, ranging in difficulty from simple arithmetic to advanced calculus, and two examinees, a fourth grader and a graduate student in statistics at the University of Chicago. Both could take a test consisting of all 1,000 items, and their scores would be very good estimates of their abilities, but this would not be an efficient use of their time. Alternatively, a test of only three items could be administered—one to measure arithmetic, one for algebra, and another one for calculus. This would be more efficient in terms of time, but we would learn very little in terms of their abilities. A better approach would be to start with an intermediate algebra item. If the fourth grader gets it wrong, he or she begins to receive easier items. If the graduate student gets it right, he or she moves to more difficult items. The process continues until the uncertainty in the estimated ability is smaller than a predefined threshold.

To use CAT, a bank of test items is first calibrated using an IRT model that relates properties of the test items (for example, their difficulty and discrimination) to the ability (or other trait) of the examinee. The paradigm shift is that, rather than administering a fixed set of items and allowing precision of measurement to vary between, or even within, individuals, CAT fixes measurement precision and allows the items to vary both in number and in content. The items are adaptively selected out of a much larger bank of items and the starting point of the adaptive testing process can also be informed by prior test results. The precision of the test can be adjusted depending on the application. For example, for an epidemiological study, less precision may be needed than in other situations, so that it would be sufficient to administer fewer items. More precision and more items may be desirable for screening in a primary care setting, while maximum precision and an even larger number of items may be needed in a randomized, controlled trial.

Gibbons said that historically CAT has been applied to unidimensional constructs in educational measurement. What is new about this work is the use of multidimensional IRT models as the foundation for CAT. This has particular advantages when measuring concepts such as depression, which are inherently multidimensional, with items drawn from cognitive or somatic domains, or domains related to mood, suicidality, or functional impairment. He said that the model used in CAT is complex, because different items may have different numbers of categories, different severity thresholds, and different abilities to discriminate high and low levels of the underlying latent variable of interest. The greatest complexity is introduced by the multidimensionality of the items. How-

ever, Gibbons noted, an important by-product of CAT is that the estimates of impairment are accompanied by estimates of uncertainty, which can be used to construct confidence intervals for the point estimates and characterize the resulting precision of the measurements. This is not possible to do in traditional mental health testing.

Gibbons pointed out that depression, and psychiatric rating scales in general (e.g., the K6, the [Patient Health Questionnaire] PHQ-9), work well at the extremes, that is, in differentiating the really depressed people from those who are not depressed. However, in the middle of the distribution, the traditional scales are less precise. With CAT, there is uniform precision because items can continue to be delivered until a desired level of precision is reached for everyone who is responding. This is possible because of the very large item banks.

Gibbons shared some results from his research on depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.1 He pointed out that for depression—using a standard error of 0.3—the precision is about 5 points on a 100-point scale. Table 5-1 shows that with this standard error they were able to maintain a correlation of 0.95 with the 400-item depression bank, using an average of only 12 adaptively administered items. Relaxing the standard error to 0.4, which is about 7 on a 100-point scale, only an average of six items was needed to maintain a correlation of 0.92 with the 400-item bank. The results for anxiety are virtually identical using an average of about 12 items. The correlation for anxiety was 0.94 with a 430-item bank. Bipolar (mania) had a lower correlation of 0.91, using an average of 12 items: the reason may be that the mania items were dichotomous. Generally, polytomous items, ordinal items, or multicategorical items work best in multidimensional IRT-based CAT models.

Gibbons also described work in which he has participated to develop the first computerized adaptive diagnostic screener. He reminded workshop participants that for diagnostic screening the goal is to identify the tipping point between the probability of a positive and a negative diagnosis, while for measurement the goal is to differentiate severity levels. The researchers found that, with an average of four items and a maximum of six items, administered in an average of 36 seconds, they could maintain

________________

1 See Gibbons, R.D., Weiss, D.J., Pilkonis, P.A., Frank, E., Moore, T., Kim, J.B., and Kupfer, D.K. (2012). The CAT-DI: A computerized adaptive test for depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69, 1104-1112.

Gibbons, R.D., Weiss, D.J., Pilkonis, P.A., Frank, E., Moore, T., Kim, J.B., and Kupfer, D.J. (2014). Development of the CAT-ANX: A computerized adaptive test for anxiety. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 187-194.

Achtyes, E.D., Halstead, S., Smart, L., Moore, T., Frank, E., Kupfer, D., and Gibbons, R.D. (2015). Validation of computerized adaptive testing in an outpatient non-academic setting. Psychiatric Services, 66(10), 1091-1096.

TABLE 5-1 Results from Simulated Computerized Adaptive Testing

| Test | Standard Error Term | Correlation | Mean Number of Items | Minimum Number of Items | Maximum Number of Items |

| Depression | 0.30 | 0.95 | 12 | 7 | 22 |

| 0.40 | 0.92 | 6 | 4 | 16 | |

| Anxiety | 0.32 | 0.94 | 12 | 6 | 24 |

| Bipolar Disorder | 0.45 | 0.91 | 12 | 6 | 24 |

SOURCE: Workshop presentation by Robert Gibbons, September 2015.

the sensitivity of 0.95 and specificity of 0.87 of an hour-long face-to-face Structured Clinical Interview for DSM for major depressive disorder.

Gibbons also described an independent validation study that produced similar results.2 He and his colleagues used a highly comorbid community mental health sample (N = 150) and found a sensitivity rate of 0.96 and a specificity rate of 1.0 for major depression disorder in comparison with the control population. Of the people who participated, 97 percent said that the test results accurately reflected their mood, and 86 percent preferred the computer interface to other testing modes. He noted that even older people who had less experience using computers were comfortable using it.

Gibbons also presented new data on detection rates in emergency rooms that involved screening approximately 1,000 people in the emergency department at the University of Chicago. Using a confidence level of over 50 percent, 26 percent of the participants screened positive for major depressive disorder. This proportion dropped to 22 percent with a confidence level of over 90 percent. When the CAT for depression was combined with the CAT diagnostic screener, 7 percent were found to be in the moderate to severe range. In addition, 3 percent had a positive suicide screen, which means ideation, in addition to intent, a plan, or recent suicidal behavior. Gibbons said that these are the people who need treatment, but, remarkably, these patients were not coming to the emergency department for a psychiatric indication. A health services implication of the findings is that the rate of emergency department visits in the past 2 years was three times higher for those who screened in the moderate to severe range than for those who screened in the none to mild range. The

________________

2 Achtyes, E.D., Halstead, S., Smart, L., Moore, T., Frank, E., Kupfer, D., and Gibbons, R.D. (2015). Validation of computerized adaptive testing in an outpatient non-academic setting. Psychiatric Services, 66(10), 1091-1096.

researchers also found the rate of hospitalizations in the past 2 years was four times higher among the moderate to severe positive screens in comparison with the mild to none negative screens. Gibbons suggested that there are enormous financial implications in terms of the service needs of depressed patients who show up in the emergency department for other than psychiatric indication.

Gibbons briefly described a study conducted in Spain and with Latino populations in the United States to examine whether or not the items mean the same thing in different cultures. With an IRT-based system of measurement, it is possible to look at the discrimination parameter and see whether there is differential item functioning. It is also possible to determine whether there are items that are excellent discriminators of high and low levels of depression in one culture but work less well in another culture (e.g., Latino population). Examining detection rates in primary care in Barcelona and Madrid, where depression screens were administered in Spanish, the researchers found similar high rates as in the emergency room study conducted at the University of Chicago.

Gibbons then described possible future directions for CAT in mental health assessments. He said that CAT has important applications for screening and monitoring in primary care; for conducting inexpensive phenotyping for large genome-wide association studies; for psychiatric epidemiology; and in comparative effectiveness and safety studies. Gibbons said he will also be using CAT as part of the Kiddie CAT study to assess the dimensions of depression, anxiety, mania, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. The study involves an item bank of 1,200 items for parents and 1,200 items for children, and the goal is to develop diagnostic screeners and measures for each of the dimensions. CAT can also be applied to autism, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use, and research domain criteria dimensions (see Chapter 2). Gibbons said that CAT can also have a very useful application in military populations, for which the risk of suicide within the first 4 years after discharge is four times higher than the rate in the general population. One advantage of CAT is that the mental health applications can all be used in cloud computing environments, unless there is a reason not to do that, such as when screening for suicide.

Gibbons concluded his presentation with a demonstration of the CAT depression screen and a screen for suicide risk. After administering the test, the results show whether the depression screen was positive or negative and the severity level, along with the associated confidence level and precision. There is also a suicide warning displayed on the results screen. Gibbons noted that after the CAT is administered, a text message and email can be sent to several recipients, such as clinicians or a suicide hotline, as needed.

After the test is completed, it is possible to look up details about the interview, such as what questions were asked of the person, what the summary scores were, and how long it took to answer each question. If some items took longer than the rest, such as the suicide items, a clinician might want to follow up. These are additional unobtrusive measures that systems of measurement such as CAT can provide.

THE PATIENT REPORTED OUTCOME MEASUREMENT SYSTEM

David Cella (Northwestern University) discussed the Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS), a project under the Common Fund, which supports cross-cutting, trans-NIH programs. There was interest in standardizing a range of measures including those for pain, depression, physical function, social and cognitive function, dexterity, as well as other domains across different mental and physical diseases.

The PROMIS Cooperative Group, which operated from 2004 to 2015, was widely considered to be one of the success stories of the Common Fund. The project involved more than 250 investigators and more than 50 protocols, aligned around evolving PROMIS standards. More than 50 grants were funded not only by Common Fund grants, but also by different NIH institutes and other government and nongovernment entities, including the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the Department of Defense, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Army, foundations, and industry.

Across the qualitative and quantitative databases, information was collected from more than 50,000 adults and children. All of the measures are available in English and Spanish, and many subsets of item banks are also available in Chinese and other languages. For adult health measures, there are about 1,500 items, which populate 71 distinct item banks and scales and are available in 20 languages. For pediatric health measures, there are about 280 items that make up about 40 distinct banks and scales in 10 languages.

From the beginning, PROMIS has been domain specific, not disease specific. By definition and by design, the work has focused on measuring traits, attributes, moods, and functional areas that cut across diseases. Cella said that item banks, as Gibbons’ talk illustrated, are a great way to accomplish that. He defined item banks as large collections of items that measure a single domain, which is the specific feeling, function, or perception of interest. The domains cut across diseases.

As starting point for its domain framework, PROMIS uses the World

Health Organization (WHO) tripartite definition of health as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being. PROMIS has also been linked to the more recent WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health model. The domains of physical health are symptoms and function; the domains of mental health are affect, behavior, and cognition; the domains of social health are relationships and function. The item banks are spread across this broad framework, and they are unidimensional, although the PROMIS team has also experimented with multidimensional IRT and for some purposes uses a bifactor model developed by Robert Gibbons.

The goal for the PROMIS metrics is to capture the full spectrum of a concept or domain, such as physical functioning from 0 to 100 (e.g., getting out of bed, standing without losing balance, walking from one room to another, walking a block, jogging for 2 miles, running for 5 miles) and only ask those questions that are relevant. The approach is similar to that for a CAT environment. The metrics for PROMIS have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. The items in almost all cases are referenced to the U.S. general population.

One of the PROMIS tools is the Global Health Scale, which is a 10-item measure that can be thought of as a shorter version of the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12). It is similar to the SF-12 in that it produces a global physical health score and a global mental health score. The index is conceptually comparable to the SF-12 and has the advantage of being free and publicly available. The Global Health Index is derived from item banks using CAT and averages about four or five items per domain. For some domains, for example, depression, very often there are just three items.

Also derived from item banks are fixed length forms of 4 to 10 items that are available “off the shelf,” by individual domain. Short forms can also be customized for specific needs. If enough is known about a population, items can be selected that work better in a given range of the trait that is to be measured. PROMIS also has fixed length forms that cover seven domain health profiles: anxiety, depression, fatigue, pain, sleep, physical function, and role satisfaction. These profiles can also be used as short forms that are pulled from the calibrated item banks. Depending upon the desired sample size and level of precision needed, there are short forms that contain four, six, or eight items per domain.

As an example of how PROMIS is used, Cella said that the American Psychiatric Association is using the PROMIS depression and anxiety short forms in its DSM-5 field trials. In their approach, the PROMIS short forms are administered if screening items are answered with mild symptomatology evident. The PROMIS anxiety and depression short forms used are 6-8 items long, and each question uses a five-point frequency rating (never,

rarely, sometimes, often, always). The t-score can then be identified from a patient’s raw score, as long as all items have been completed. There are also cross-cutting Level 1 and Level 2 measures for child anxiety, depression, sleep, and anger. These cross-cutting measures are recommended to track severity of symptoms over time and as indicators of remission or of exacerbation of symptoms. They are completed at regular intervals, as clinically indicated, and consistently high scores identify an area that needs more detailed assessment, treatment, or follow-up.

Cella noted that a 2013 report3 compared the DSM-5 approach for diagnosis (in other words, the use of information from cross-cutting measures, diagnostic criteria, and diagnostic-specific severity measures) to the DSM-IV approach for various disorders in pediatrics, and found that 80 percent of clinicians reported that, in their clinical experience, the DSM-5 approach was better or much better than the DSM-IV approach. Examining the same question by specific disciplines (i.e., psychiatrists, marriage and family therapists, clinical social workers, and counselors) again showed that about 70 percent of providers preferred the DSM-5 approach. Similar results were observed for adult patients who thought their clinicians would better understand their symptoms.

Cella also discussed how PROMIS measures are being used by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Healthy People 2020 initiative. The measures have been approved for use in Healthy People 2020 and the National Health Interview Survey. The objectives were to increase the proportion of adults who report good or better physical health-related quality of life and to increase the proportion of adults who report good or better mental health-related quality of life. Four PROMIS global mental health items were approved as part of this effort, with excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor as response categories:

- In general, would you say your quality of life is….

- In general, how would you rate your mental health, including mood and ability to think?

- In general, how would you rate your satisfaction with social activities/relationships?

- How often have you been bothered by emotional problems?

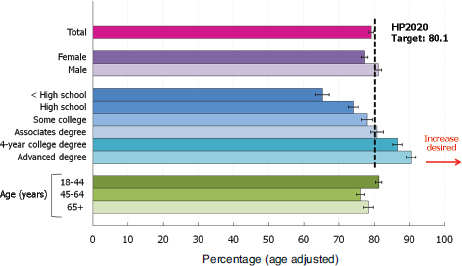

Figure 5-1 shows 2010 NHIS data on the proportion of adults who reported good or better mental health among different demographic groups. The 2020 target that was proposed and approved by the Federal

________________

3 Moscicki, E.K., Clarke, D.E., Kuramoto, S.J., Kraemer, H.C., Narrow, W.E., Kupfer, D.J., and Regier, D.A. (2013). Testing DSM-5 in routine clinical practice settings: Feasibility and clinical utility. Psychiatric Services, 64(10), 952-960.

FIGURE 5-1 Adults who report good or better mental health, by demographic characteristics: 2010.

NOTE: Data (except data by age group) are age adjusted to the 2000 standard population.

SOURCES: Healthy People 2020 Spotlight on Health. Available: https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/HP2020_SpotlightOnHealthHRQOL.pdf [January 2016]. Data from the National Health Interview Survey.

Interagency Working Group is the dotted line in the figure. The current 2010 status is the top magenta line. With regard to mental health, fewer women report good or better mental health than men. Education is a strong predictor of mental health, with a disparity in lower educational levels as shown by below high school, high school, and some college being below the line. People with advanced degrees are above the line. Cella also noted that there is less of an age disparity in mental health than in physical health (not shown in this figure).

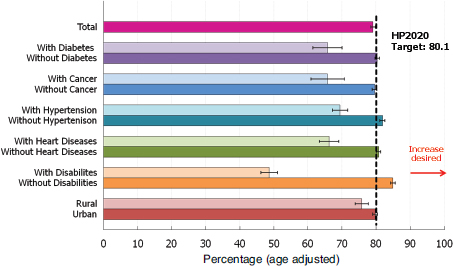

Figure 5-2 also shows adults who reported good or better mental health but compares those with and without different physical disorders. The figure illustrates the mental health disparity among people with and without such conditions as diabetes, cancer, hypertension, heart disease, and, especially, disabilities.

Cella closed his presentation with a discussion of a project called PROsetta Stone. Though funded through the National Cancer Institute, its goal is to develop and apply methods to link the PROMIS measures with other related patient-reported outcome measures in order to have a common, standardized metric. Cella pointed out that the project website

FIGURE 5-2 Adults who report good or better mental health, additional comparisons: 2010.

NOTE: Data are age adjusted to the 2000 standard population.

SOURCES: Healthy People 2020 Spotlight on Health. Available: https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/HP2020_SpotlightOnHealthHRQOL.pdf [January 2016]. Data from the National Health Interview Survey.

has about four or five dozen tables that show different instruments linked and calibrated onto a common metric.4

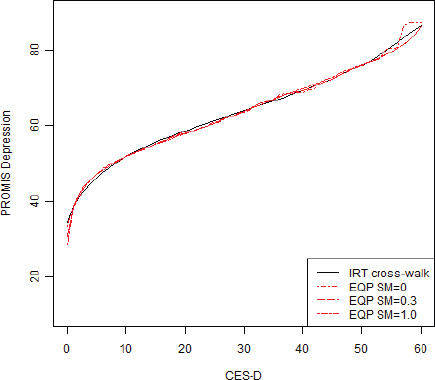

Using the example of depression to link measures, the researchers first coadministered the PROMIS depression measure, the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) measure, the [Patient Health Questionnaire] PHQ-9, and the Beck Depression Inventory-II, then calibrated all of the items. Figure 5-3 shows the cross-walk function between CES-D and PROMIS depression, with the scores mapping on top of one another. This is also true for other metrics.

Cella and his colleagues also produce a raw score to t-score conversion table that shows, for example, a PHQ-9 score and the PROMIS t-score equivalent. A PHQ-9 score of 10, which is moderate, is around 59 on a PROMIS t-score: 60 is a common t-score to use for mild to moderate symptomology and 70 for more severe symptomology, which would be a PHQ-9 score of around 19 or 20. He concluded by saying that the PROMIS team is working with organizations like the National Quality Forum and

________________

4 See http://www.prosettastone.org [December 2015].

FIGURE 5-3 CES-D to PROMIS depression: IRT cross-walk function and equipercentile functions with different levels of smoothing.

NOTES: EQP, equipercentile; sm, post-smoothing. The IRT cross-walk function is based on fixed parameter calibration.

SOURCE: Choi, S.W., Schalet, B., Cook, K.F., and Cella, D. (2014). Establishing a common metric for depressive symptoms: Linking the BDI-II, CES-D, and PHQ-9 to PROMIS depression. Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 513-527. Published by the American Psychological Association, reprinted with permission.

National Committee on Quality Assurance to replace the use of the PHQ-9 with PROMIS metrics.

James Jackson (University of Michigan) asked Cella about the advantages of using PROMIS over the PHQ-9 depression measure. Cella replied that the PHQ-9 was driven by the DSM-IV and developed as a diagnostic tool, but it is now used as an outcome tool. For example, the PROMIS depression metric is on a near-interval level scale, so it is possible to begin to understand this underlying trait in a way that is not tied to DSM-IV

clinical criteria. Regier pointed out that the PHQ-9 does try to integrate the multiple domains of major depression, as opposed to a univariate domain of depression alone. It includes mood, suicide risk, as well as various cognitive issues, which are not part of the depression univariate domain.

Regier then asked Gibbons about whether a multidimensional approach would enable researchers to capture more of the syndromal nature of mental disorders that contain more than just one domain. Gibbons replied that it could be done, but it would depend on what is being measured. Gibbons also commented on the PHQ-9, which he said in some sense is multidimensional, but it is scored with a single-value index. For example, one can have a PHQ-9 score of 13 for 4, 5, or 13 different reasons. In other words, one can have very different symptomology and have the same score. Using multidimensional IRT, it is possible to define the underlying domains from which the items were drawn, in the same way as the authors of the PHQ-9 did. It is also possible to preserve those underlying constructs and either map an unbiased estimate onto the construct of depression or score the individual subdomains and come up with something that is more multidimensional. If depression is composed of cognitive, mood, suicidality, sleep, and two or three other subdomains, it is possible to say that it is really depression, anxiety, and maybe some mania. It also becomes possible to obtain separate scores on each of the subdomains or obtain an overall composite score.

Gibbons also said that as part of one of his current projects he and his colleagues are working with 300 items on depression, mania, and psychosis, and are trying to produce an overall single-value index of severe mental illness that maintains the inherent multidimensionality of the item bank. One could then also score the individual subdomains, but that is not something his team has done yet.

Cella added that the issue of dimensionality is not all science or purely measurement, but also art to some extent. For example, the K6 includes four depression-like items and two anxiety-like items, and it fits an IRT model. However, it is not clear whether it is two-dimensional or one-dimensional. It is possible to make it one-dimensional. In fact, the bifactor model that Gibbons developed helps do that by removing some of the noise to purify the signal and allow content to stay in.

Cella went on to say that, for reasons related to conceptual elegance, PROMIS includes a separate depression/anxiety item bank, because these naturally work together. The assessment of both can be shortened, as Gibbons illustrated. If the depression test is administered, the anxiety test will be shorter because one knows where to start. It might only be shorter by one item because these polytomous items are efficient at determining where someone should start.

Robert Krueger (University of Minnesota) emarked that psychopathology in itself has a structure to it. In work with others, he and his colleagues looked at the structure of mental disorders using data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement.5 They found a meaningful general factor that tends to bifurcate into internalizing and externalizing kinds of presentations, as well as further layers to the structure. Krueger noted that there is some recognition in DSM-5 that mental disorders have an underlying structure. If the goal is to measure overall psychopathology as a construct, he thought it would be possible to develop an efficient CAT method for doing so, and it would be akin to what has been called “distress” throughout the workshop.

Cella said that Gibbons’ work is closer to doing what Krueger referred to than the PROMIS. Gibbons said that PROMIS has developed a very large series of measures to study a wide range of concepts using unidimensional IRT. The fact that it is unidimensional makes it more difficult to build very large item banks. The measures that Gibbons and his colleagues developed for depression, anxiety, and mania that were developed through CAT have been developed, with much larger item banks. The multidimensional IRT makes it possible to maintain that huge item bank, which allows for the adaptive selection of items that are tailored for each person. Because of the huge item bank, they would not be giving the same person the same items over and over again. As the item bank grows, CAT works better than a short-form test because it also provides uniformity of measurement throughout. Gibbons added, however, that it is very expensive to perform the original calibration in order to be able to maintain very large item banks.

Clinical Utility

Mark Olfson (Columbia University) commented that it is clear that the CAT is elegant and that getting to decisions more promptly, with fewer items, has advantages, if it can be integrated into large-scale surveys. However, he wondered whether the goal for both the CAT and the PROMIS is to be introduced into clinical practice. Gibbons replied that the CAT is suitable for the identification of people who need treatment. People who are not identified and not treated tend to consume health care services at high rates and are also at risk for sequelae, such as suicide. Once people are identified, CAT-based measurement is also ideal for

________________

5 Blanco, C., Wall, M.M., He, J-P., Krueger, R.F., Olfson, M., Jin, C.J., Burstein, M., and Merikangas, K.R. (2014). The space of common psychiatric disorders in adolescents: Comorbidity structure and individual latent liabilities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(1), 45-52.

longitudinal assessment to determine whether people are responding to treatment and for making changes to the treatment plan.

Gibbons said that he is working on a project related to depression treatment, where frequent measurements are taken. The PHQ-9 or K6 are not suitable for administration every 30 minutes. When a CAT-based approach is used, two successive measurement occasions would not involve the same items, and thus the threat of response bias is lowered. He also noted that the test-retest reliability of the PHQ-9 is 0.80, and the test-retest reliability for the depression CAT test is 0.92. Despite asking different questions, the reliability of the estimates is improved, because CAT produces more precise estimates of depressive severity than traditional fixed-length tests.

From the perspective of a clinician, Olfson said the reason the PHQ-9 is so popular is its items are questions that clinicians want to ask because of their relevance to the person’s mental health status. Clinicians are not just interested in the dichotomous decision of whether the person passes a threshold or not, which is possible to ascertain more rapidly and efficiently taking advantage of IRT. They want to know, within each of these domains, how well a person is sleeping, what his or her appetite is like, and whether they are having difficulty with decision making; clinicians will intend to follow up on any of the items that are positive. Ultimately, clinicians and patients may not be interested in the underlying construct but rather in probing more deeply about problem areas.

Gibbons said that his experience in working with clinicians has been just the opposite. The CAT helps them explore those areas where there is a density of symptomology. In fact, some clinicians use it as part of the therapeutic process. Patients go through the CAT, and then they review the responses and discuss what they were experiencing and why they answered in a certain way. Gibbons acknowledged that the CAT has some potential limitations. For example, the CAT can produce a valid measure of depression severity without having to ask questions from all possible domains, which means that if a clinician’s goal is to learn about a particular symptom of interest that was not adaptively administered, he or she would have to supplement what was learned from the CAT.

Cella noted that on ClinicalTrials.gov, where people using PROMIS tools have the opportunity to use CAT, custom forms, or off-the-shelf short forms, the choice has been short forms, by a 5-to-1 margin over other options. He said that the reason might be that the CAT technology is not very accessible. There is also the desire of clinicians, clinical researchers, and regulators to want to see the answers to the same questions over time.

Krueger commented that one way to think about this is to consider the breadth of concepts that one would ideally like to cover and the amount of time that is available to cover them. There are many areas that

are important to screen for, at least briefly, and if time is limited, CAT can be enormously useful.

Implications of the CAT’s Precision in Identifying Disorders

Lisa Colpe (National Institute of Mental Health) commented that she was really impressed with the CAT and its precision, especially for measures that reference the past 2 weeks. She wondered whether SAMHSA would have a “duty to treat,” if, based on a CAT method, one could identify people who are in need of treatment, given that the CAT approach can identify people who have the disorder now and not just “within the past year,” as is the case with most national surveys. Typically, in the arena of public health, one does not conduct a screener unless it is possible to also take the next step and either do further assessment or offer treatment.

Gibbons replied that this comes up in his work of suicide screening. His team will only do suicide screening face to face so that if there is an issue, appropriate follow-up can be done. The question is whether something should be done even for untreated depression, and the right answer is, of course, yes, he said, because untreated depression leads to high health care costs and is also associated with a high suicide rate. Colpe said that procedures would have to be developed to address this issue, and perhaps participants could be given the instruction to go to a designated place for assessment or treatment, or could even be directed to an online cognitive behavioral therapy course, as needed.

Dean Kilpatrick (Medical University of South Carolina) said that research studies that involve sensitive topics typically have people available to help out, which is the standard for clinical epidemiological studies or epidemiological studies addressing mental health or substance use issues. Colpe replied that the standard at NIMH is to provide all participants with information about where they could go for treatment if they wanted to do so, after answering questions that are part of a study. However, collecting information about the past 2 weeks is different than asking about the past year, which is more typical for national surveys.

Calibrating for Language and Literacy

Thinking about SAMHSA’s goals, Regier asked whether the PROMIS and the CAT have been calibrated well enough to be adapted to the entire U.S. population, including to specific demographic groups. Along those lines, Neil Russell (SAMHSA) also wanted to know whether the literacy level of the questions has been evaluated.

Gibbons replied that the literacy issue is one of the reasons that the questions are read out loud to the patients by a computer. One advantage

of CAT is that it allows researchers to examine the issue of whether there are cultural differences. For example, if an item is a bad discriminator of high and low levels of depression among Latinos, then the item would not be included. Gibbons and his colleagues are continuing research on this topic to improve the CAT approach.

Use of Computerized Adaptive Testing by Federal Agencies

Stephen Blumberg (National Center for Health Statistics) commented that he considers computerized adaptive testing to be very useful in certain circumstances, but in the interest of transparency, government agencies need to be able to include in their datasets not just the scores, but also every item that the person responded to and exactly how the person responded. This is not impossible, but the documentation may be very extensive. He wondered whether government agencies would find the use of CAT more difficult to justify and whether there are any government agencies that are currently using CAT. Jonaki Bose (SAMHSA) replied that SAMHSA has used adaptive testing and that the National Center for Education Statistics also used it in an early childhood longitudinal study and in the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

Bose added that the transparency issue also raises the question of whether or not SAMHSA would be able to incorporate a proprietary set of questions in their surveys. Blumberg said that at one point NCHS was interested in such a possibility and this was discussed with the heads of all the federal statistical agencies: the conclusion was that a proprietary scale could only be used if it can be disclosed exactly what items are in the scale.

Technology for Administering CAT

Kilpatrick commented that CAT-type approaches have many benefits, but they can be confusing to implement. There would need to be a lot of education, so that people really understood how it works. Even if people understood it well, some might not be convinced about the advantages, given the transparency concerns. He asked whether CAT could be used on a free-standing laptop or tablet without Internet access, if one was interested in integrating it into a survey.

Gibbons replied that the system they have developed is designed for entire health care systems, so it primarily works through the Internet. He explained that their prototype versions are on dedicated computers, but University of Chicago undergraduates administered the tests in emergency departments, using tablets. Tablets were also used to collect data in primary care settings in Barcelona and Madrid, where Internet access

was limited. He added that the team is in discussion with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) about the possible use of CAT, and they plan on giving the VA an executable version of the program that can be uploaded to their computers. Ultimately, from the perspective of Gibbons and his colleagues, the vision would be a cloud computing environment in which CAT could be administered on home computers, tablets, or cell phones.