4

Abilities Required to Manage and Direct the Management of Benefits

As discussed in Chapter 2, the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) uses the term capability to refer to “a beneficiary’s ability to manage or direct the management of his [or] her Social Security funds” (SSA, 2015b). Incapability is a determination by SSA that an individual beneficiary is unable to manage or direct the management of his or her benefits as a result of mental disability or, sometimes, physical disability. Akin to the legal definition of incompetence,1 incapability is a dichotomous determination made by an authoritative body. Making such a determination requires an assessment of the individual’s financial capability.

For SSA to consider an individual capable, he or she must be able either to manage or to direct the management of his or her benefits. Although the abilities required to manage and to direct the management of one’s funds clearly overlap, there are differences as well. Managing one’s own funds means one is fully and independently responsible for managing the funds in a way that routinely meets one’s needs and goals. If one can manage one’s funds, one presumably also can direct the management of the funds. Even if someone is not capable of fully and independently managing his or her own funds, that person may still be capable of directing the management of the funds by someone else. For example, people with a mental impairment may be able to direct another to manage their funds based on their goals, such as

___________________

1 In legal terms, incompetency refers to a determination by the courts that an individual is unable to manage his or her affairs as a result of mental disability or, sometimes, physical disability. SSA uses the term “legally incompetent” to refer to one subset of beneficiaries who will automatically receive a representative payee.

paying rent on time so as not to lose their apartment, even though they themselves are not able to perform the day-to-day tasks necessary to achieve those goals. Similarly, people who are mentally capable of managing their own funds but have a physical impairment, such as quadriplegia or an inability to speak, that makes them physically unable to accomplish the tasks required may still be able to direct someone else to perform those tasks for them.

As discussed in Chapter 1, the committee broadens SSA’s conception of capability to encompass the full realm of one’s finances, defining the term financial capability as managing or directing the management of one’s funds in a way that routinely meets one’s needs and goals. In the context of SSA, financial capability refers to a beneficiary’s managing or directing the management of SSA funds in a way that routinely2 meets his or her basic needs. Financial competence and financial performance both contribute to financial capability (see Figure 1-1 in Chapter 1). This chapter provides a conceptual overview of these components of financial capability and the cognitive and behavioral processes underlying them. It also includes discussion of mental and physical disorders that may affect financial capability. Chapter 5 addresses methods and measures for assessing financial capability.

FINANCIAL COMPETENCE

Financial competence refers to the financial skills one possesses, as demonstrated through financial knowledge and financial judgment, typically assessed in a controlled (e.g., office or clinical) setting. Financial performance refers to one’s degree of success in handling financial demands in the context of the stresses, supports, contextual cues, and resources in one’s actual environment (i.e., the actual use of one’s financial knowledge and judgment in concrete, real-life situations). For example, a person may be fully competent in appreciating the importance of retirement savings, but at the level of performance may not have sufficient self-control, foresight, or planning skills to actually save money for retirement. Individuals must both decide on their financial goals and take the steps necessary to influence the realization of those goals to possess successful financial self-management. Thus, successful financial performance involves intact cognitive and behavioral components. Importantly, these are complex interactions that cannot be reduced to a single score or algorithm. As Lichtenberg (2015) notes, “People are more than the sum of their cognitive abilities.”

___________________

2 The committee recognizes that circumstances and personal preferences at times may require or lead individuals to forgo a basic need, such as food. Nevertheless, individuals’ overall behavior may still reflect an ability to use their benefits to meet their basic needs over time. When that occurs, their needs are being met routinely, in the sense in which that term is used in this report.

Financial Knowledge

The first component of financial competence is financial knowledge, which encompasses the declarative and procedural knowledge required for the effective management of one’s finances. Declarative knowledge refers to knowing that something is the case. As it relates to financial knowledge, declarative knowledge is “the ability to describe facts, concepts, and events related to financial activities” (Marson, 2015; Marson et al., 2000; Moye and Marson, 2007, p. P7), such as arithmetic knowledge (e.g., basic numeracy), semantic and conceptual knowledge of financial terms and associated concepts (e.g., currency values, bills, checks), and knowledge of one’s finances (e.g., how much money one has). Requirements for declarative financial knowledge are evolving with technological advances. For example, successful financial management today may involve the use of ATMs (automated teller machines) and online banking. In some cases (e.g., severe intellectual disability), individuals may never acquire sufficient declarative financial knowledge to be able to manage or direct the management of their finances. In other cases (e.g., neurodegenerative processes such as Alzheimer’s disease or semantic dementia), individuals may lose their semantic and conceptual knowledge of financial terms and concepts (e.g., paying bills, using currency) and other aspects of financial knowledge, including knowledge of their assets, income, and the like.

Procedural knowledge refers to knowing how to do something. Procedural financial knowledge is “the ability to carry out motor based, overlearned practical financial skills and routines such as making change and writing checks,” as well as online banking procedures (Marson, 2015; Marson et al., 2000; Moye and Marson, 2007, p. P7). An individual may possess or retain some level of declarative financial knowledge yet lack or have lost the procedural knowledge required to execute the appropriate behavior. For example, a woman with “more advanced” dementia “was observed to grapple with calculating what payment a cleaner required and how to count the necessary money, nonetheless, she was readily able to identify that he was doing a routine job for the couple and therefore needed to be paid” (Boyle, 2013, p. 559). Such individuals still may be able to direct the management of their financial affairs even though they have lost the procedural knowledge required to perform the actions themselves. On the other hand, a study of individuals with mild cognitive impairment indicated that they retained the purely procedural task of cash transactions, while other performance skills (e.g., bill payment, understanding and using a bank statement) with more complex conceptual components were compromised (Okonkwo et al., 2006).

Financial knowledge is cognitively mediated and influenced by contextual factors related to the environment and the person. Environmental

factors include individuals’ opportunities to acquire the declarative and procedural knowledge required for financial competence. Personal factors include the presence of psychiatric (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder), neurologic (e.g., traumatic brain injury, dementia, mild cognitive impairment, stroke), and other medical (e.g., disorders associated with severe pain, debilitation, or hypoxia) conditions (Marson, 2013) that may affect individuals’ cognitive function. It is worth noting that financial knowledge encompasses a wide range of declarative and procedural knowledge—from basic financial transactions (purchases, bill paying) to investing and compound interest. For SSA’s purposes of determining financial capability, the committee is concerned primarily with the basic knowledge and skills individuals must have to use their benefits to meet their basic needs for food, shelter, and clothing.

Financial Judgment

The second component of financial competence is financial judgment, defined by the committee as possession of the abilities required to make financial decisions and choices that serve the individual’s best interests.3 As discussed in Chapter 1, the committee recognizes the subjective nature of determining an individual’s “best interests” and has adopted the minimally restrictive standard of satisfying the basic needs of food, shelter, and clothing for purposes of this report. The committee understands that personal values will affect the ways in which individuals choose to satisfy their basic needs. In addition, when financial resources are limited, individuals often must decide which of their basic needs will take priority, and personal values will affect those decisions as well.

Decision making in the financial realm, like decision making for medical treatment or for participation in research, can be viewed as a specific area of decision making more broadly. The abilities required to make financial decisions and choices in one’s best interests (financial judgment) can be extrapolated from the extensive literature on decision-making capacity in medical and research contexts. Various authors have postulated requisite components of decision-making capacity for the purpose of consenting to medical treatment (Appelbaum and Grisso, 1988; Drane, 1985; President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1982; Roth et al., 1977; Tepper and Elwork, 1984). During the past 30 years, consensus has formed around

___________________

3Marson and colleagues (2000) identify judgment as the third component, along with declarative and procedural knowledge, of what they call financial capacity. They define judgment as “the ability to make financial decisions consistent with self-interest, in both everyday and also novel or ambiguous situations” (Moye and Marson, 2007, p. P7).

four abilities that are relevant to individuals’ capacity to make treatment decisions (Grisso, 2005, pp. 398-399; see also Charland, 2015; Moye and Marson, 2007)4:

- The ability to communicate a choice refers both to the ability to indicate a choice among a variety of alternatives and to “the ability to maintain and communicate stable choices long enough for them to be implemented” (Appelbaum and Grisso, 1988, p. 1635). This does not mean that a person’s choices may not vary over time, only that repeated, rapid reversals of choice without reasonable justification may indicate impaired decision making. Impaired consciousness, thought disorders, impaired short-term memory, or an extreme degree of ambivalence may disrupt an individual’s ability to communicate reasonably consistent choices (Appelbaum and Grisso, 1988).

- The ability to understand relevant information includes an individual’s abilities to receive and remember information relevant to the decision and to comprehend that information, as well as to understand causal relations, associated risks and benefits, the likelihood of different outcomes, and the individual’s role in the decision-making process (Appelbaum and Grisso, 1988). These abilities may be impaired by deficits in attention, intelligence, and memory.

- The ability to appreciate the relevance of the information extends the notion of a person’s comprehension of relevant information to an appreciation of what that information means for the individual in his or her particular situation. The person recognizes how the information applies to and is significant for his or her own circumstances. Such appreciation includes the values that the individual places on each risk and benefit or potential outcome. The ability to appreciate the relevance of information may be impaired by pathologic distortions or denials stemming from cognitive or affective impairment or a delusional perception of the nature of one’s situation (Appelbaum and Grisso, 1988).

- The ability to manipulate information rationally refers to the use of logical processes to compare and weigh the various risks and benefits associated with different courses of action and to reach

___________________

4 Some authors recognize a stable and minimally consistent set of personal values as a fifth element of decision-making capacity (Buchanan and Brock, 1989, pp. 24-25; Charland, 2015; President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1982, pp. 57-58). Personal values play a role in individuals’ weighing of risks and benefits and selection among alternative choices (Charland, 1998, 2015; President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1982).

conclusions that are logically consistent. A number of factors can affect these processes, including “psychotic thought disorder, delirium and dementia, extreme phobia or panic, anxiety, euphoria, depression, and anger” (Appelbaum and Grisso, 1988, p. 1636).

Although studied in the context of medical decision-making capacity, this model is applicable to other decisional contexts, such as financial decision making, as well.

Lichtenberg (2015) highlights the importance of metacognition and self-awareness in decision making and successful financial interactions. Persons with impaired self-awareness may perceive that they are managing their finances effectively but in fact may be making errors and experiencing negative consequences (Hsu and Willis, 2013; Okonkwo et al., 2008; Williamson et al., 2010). Additionally, there is a risk that those with access to money but with limited decision-making capacity may be vulnerable to undue influence and potential fraud. Self-awareness, the ability to evaluate one’s performance, and the ability to make adjustments in response to feedback are related to executive functioning. Individuals with developmental or acquired brain injuries, as well as those with dementia or severe psychiatric disorders, are vulnerable to impairment of metacognition. Substance use and dependence can lead to difficulties with working memory, impulsivity, planning, problem solving, and decision making. Importantly, some individuals with conditions such as dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease or early frontotemporal dementia may retain basic skills related to financial knowledge but suffer from impaired judgment and the inability to use those skills to meet their needs or protect their interests (Marson, 2013). The cognitive domains relevant to financial competence are reviewed below.

Cognitive Domains Relevant to Financial Competence

The cognitive domains relevant to financial competence (knowledge and judgment) include general cognitive/intellectual ability, attention and vigilance, learning and memory, and executive function (Knight and Marson, 2012; Okonkwo et al., 2006), as well as social cognition and language and communication. These domains should be not viewed as discrete functions but rather as interrelated and overlapping. For example, intact attention is required for an individual to learn and remember information. Thus, although the cognitive domains are discussed separately here, the committee appreciates that the interactions among them are complex, and that noncognitive factors may influence each domain as a whole as well as the “micro-level skills” each entails.

General Cognitive/Intellectual Ability

General cognitive/intellectual ability includes reasoning, problem solving, and meeting cognitive demands of varying complexity (IOM, 2015, p. 146). Intellectual disability affects functioning to varying degrees in three areas: conceptual (e.g., memory, language, reading, writing, math, knowledge acquisition); social (e.g., empathy, social judgment, interpersonal skills, ability to form and to maintain friendships); and practical (e.g., self-management in such areas as money management) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 37). Impaired cognitive/intellectual ability can affect individuals’ acquisition of the math concepts and skills needed for financial competence. Written math skills have been identified as the primary predictor of overall financial competence5 (Sherod et al., 2009).

Attention and Vigilance

Attention and vigilance are essential components of higher levels of multifactorial cognitive processing and memory. The Occupational Information Development Advisory Panel (OIDAP, 2009) established by SSA defines attention and vigilance as constituting the ability to focus sustained attention in an environment with ordinary distractions. Impairments in this domain may result in difficulties in attending to complex input, holding new information in mind, and performing mental calculations (IOM, 2015, p. 148). Poor or fluctuating attention may make an individual incapable of executing mathematical calculations, paying bills, managing a bank statement, making financial decisions, or conducting financial interactions. Impaired attention is common in individuals with psychosis, depression, dementia, brain injuries, and substance use.

Learning and Memory

Learning and memory refer to the ability to acquire, store, and retrieve information (OIDAP, 2009). New information must be encoded and available to remember and use later. Within the financial context, individuals need to remember account balances, income, expenses over a specified time (i.e., month to month), and procedures for paying bills. Memory impairment can negatively affect financial competence, with serious consequences such as forgetting to pay bills, which may lead to eviction, and the inability to track missing funds from a bank account. Verbal memory has been identified as a secondary predictor of financial competence (Sherod et al., 2009).

___________________

5 Although the authors of this study use the term financial capacity, their use of the term, which captures “a range of conceptual, procedural, and judgment skills” (Sherod et al., 2009, p. 259), is similar to the committee’s use of financial competence.

Another study found the central executive component of working memory, which may be impaired in individuals with histories of substance dependence (Bechara and Martin, 2004), to be strongly correlated with basic monetary skills, checkbook management, bank statement management, and bill payment (Earnst et al., 2001). Learning deficits can impair one’s ability to learn the basic skills (e.g., math, manipulating currency) needed to manage finances as well as to acquire new skills, such as how to use an ATM or online banking procedures. Learning and memory deficits are common in those with serious psychiatric disorders, dementia, traumatic brain injuries, and a host of neurologic conditions.

Prospective memory is the process of remembering to perform an action or intention at a future point in time (McDaniel and Einstein, 2000). Prospective memory is directly related to financial competence and performance when an individual must remember to perform a financial task or to make financial decisions that are important to daily living. For example, people may need to remember on the first of the month to pay their rent, utilities, and other bills or transfer money to an account or to conduct some other aspect of financial management. Deficits in prospective memory have been related to declines in financial competence among individuals with Parkinson’s disease (Pirogovsky et al., 2012), as well as to decreased functional performance in HIV-seropositive individuals (Woods et al., 2008). Thus, it is reasonable to consider prospective memory a potentially important factor in the ability to carry out one’s financial obligations.

Kliegel and colleagues (2002) describe four phases of prospective memory: intention formation, intention retention, intention initiation, and intention execution. Planning, as a part of executive functioning, is critical to forming an intention (e.g., I need to pay rent). In this phase, a person focuses on relevant information while ignoring irrelevant details. An interval then occurs between forming the intention and actually performing the task. During this second phase, intention retention, the individual performs other activities while needing to remember the intention, such as paying his or her rent on time. The amount of time that elapses (e.g., the month between rental payments) and the number of other activities vary. In the third phase, the person must initiate fulfillment of the intention at the defined time (e.g., get cash or a check to pay rent on the first of the month). In this complex phase, several high-level executive functions are involved, including monitoring processes, cognitive flexibility, and inhibition. Additionally, cues (e.g., using a calendar or phone reminder) may prompt the individual to begin to execute the intention. In the fourth phase, the person must fully execute the intention (e.g., deliver the cash or check to the intended payee).

Deficits in prospective memory have been widely observed in mild traumatic brain injury and may be observed in the absence of deficits in retrospective memory (Bisiacchi et al., 1996; Palmer and McDonald,

2000). Increasing evidence also indicates that deficits in prospective memory are observed in individuals with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (Hernandez-Cardenache et al., 2014; Karantzoulis et al., 2009; Kazui et al., 2005).

Executive Function

Executive function is a multidimensional construct that overlaps with aspects of attention and memory, as well as many other cognitive domains. Executive function enables individuals to engage in independent, purposeful behavior. Its components include planning, prioritizing, emotional functioning, organizing, reasoning, problem solving, decision making, responding to feedback and error correction, mental flexibility, overriding impulses, and providing inhibition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Elliott, 2003; OIDAP, 2009). Executive function has been identified as a predictor of financial competence (Sherod et al., 2009; see also Earnst et al., 2001; Griffith et al., 2010; Okonkwo et al., 2006). In the context of financial management, it is critical to understanding finances, prioritizing financial obligations, executing multistep behaviors, and directing responsible spending. In financial transactions, individuals need first to understand the concept of paying bills and which bills should be paid. Next, they need to prioritize bills and other financial obligations (e.g., rent, food, clothing, health care). They must then complete multiple steps either to execute online payment or to order and write checks, ensure the deposit of sufficient funds in their bank accounts, buy stamps for mailing, and ultimately mail the bills. Impaired executive function can result in disjointed and disinhibited behavior; impaired judgment, organization, planning, and decision making; and difficulty focusing on more than one task at a time (Elliot, 2003; see also IOM, 2015). In the financial realm, impaired executive function can lead to unnecessary purchases or withdrawals and inability to manage one’s financial commitments.

Social Cognition

Social cognition—the cognitive process responsible for helping individuals make sense of other people and themselves (Fiske and Taylor, 2013)—refers to the encoding, storage, retrieval, and processing of information and action planning with respect to other human beings and the world. Social cognition plays a major role in social and emotional development by enabling individuals to take advantage of being part of a social group (Frith and Frith, 2012). One way in which people make sense of social stimuli is by understanding such indicators as facial expressions, body gestures, physical positioning of groups of people, and tone of voice,

which signal certain perceptions of fear, disgust, security, contentment, guidance or detection of sought-after goals, and the like. Social cognition can be developed through direct instruction, such as that which occurs between a parent and child during the transfer of knowledge about preferences, attitudes, and reactions concerning objects, people, and situations. The individual learns how to avoid danger, differentiate between good and not-so-good others, and problem solve to attain goals (Fiske and Taylor, 2013; Frith and Frith, 2012).

Impaired social cognition can interfere with one’s ability to accurately read social cues that may signal financial schemes, fraudulent activity, identity theft, and the like. Engaging in financial deals or products that “sound too good to be true” may indicate problems with social cognition (among other processes) and contribute to situations in which people with disabilities are susceptible to financial exploitation.

Language and Communication

The domain of language and communication focuses on receptive and expressive language abilities, including the ability to understand spoken or written language, communicate thoughts, and follow directions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; OIDAP, 2009). In the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), the World Health Organization (WHO) distinguishes language from communication, describing the former in terms of mental functioning and the latter in terms of activities (the execution of tasks) and participation (involvement in a life situation) (WHO, 2001) (the ICF framework is discussed in greater detail later in this chapter). The mental functions of language include reception of language (i.e., decoding messages to obtain their meaning), expression of language (i.e., production of meaningful messages), and integrative language functions (i.e., organization of “semantic and symbolic meaning, grammatical structure, and ideas for the production of messages” [WHO, 2001, p. 59]). Abilities related to communication include receiving and producing messages (spoken, nonverbal, written, or formal sign language), carrying on a conversation (“starting, sustaining, and ending a conversation; conversing with one or many people” [WHO, 2001, p. 135]) or discussion (“starting, sustaining, and ending an examination of a matter, with arguments for or against” [WHO, 2001, p. 136], with one or more people), and use of communication devices (e.g., telephones, computers) and techniques (e.g., lip reading) (WHO, 2001). Language and communication are important for the acquisition of mathematical and financial concepts and skills, financial decision making (understanding relevant information and communicating choice), and financial transactions with others.

Summary

The preceding discussion outlines a number of cognitive and behavioral abilities and processes that underlie financial competence. Individuals who are financially competent, in the committee’s use of the term, possess the financial knowledge and skills to manage their finances effectively and to make financial decisions and choices that serve their best interests, at least in a controlled setting. Given the broad range of conceptual, procedural, and judgment (decision-making) skills that underlie financial competence, different types and degrees of cognitive impairment will have varying effects on individuals’ financial competence (see, e.g., Sherod et al., 2009). Depending on how and to what extent a person’s financial competence is affected, he or she may retain financial competence in some areas (e.g., bill paying) but not others (e.g., managing investments). Although such individuals may require assistance in conducting their financial affairs, they nevertheless may be able to direct the management of their funds, as discussed in the following section.

Directing the Management of Funds

Individuals who are financially competent presumably possess the financial knowledge and the conceptual, procedural, and judgment skills required to direct the management of their finances as well as to manage their finances themselves. Nonetheless, financially competent individuals may seek assistance from others in managing their affairs for various reasons, including physical impairments that make it difficult or impossible to complete certain tasks or simply a desire not to complete those tasks themselves because of a lack of time or some other reason. Conversely, people who either do not possess or begin to lose the full complement of cognitive processes and abilities needed for financial competence may still be able to direct the management of their funds.

Various scenarios may arise depending on the areas of cognitive impairment involved. One might retain financial judgment and decision making in terms of making financial choices and setting priorities while having lost the ability to execute such financial tasks as handling money to purchase items (Boyle, 2013). For example, one might know that mortgage, utility, credit card, and other bills must be paid but not be able to keep track of which bills are due when or to execute the steps required to pay them oneself. Alternatively, one might retain the ability to execute day-to-day financial tasks (e.g., transacting purchases, basic banking, bill paying) but have lost the financial judgment skills required for long-term planning or resistance to exploitation or fraud (Marson, 2013).

Some individuals will recognize that they need help and accept or seek

out the needed assistance from a family member, friend, community service organization, or other third party. In such cases, the person may be able to direct the management of his or her funds by asking for assistance in the areas in which it is needed while retaining as much control of the funds as possible. In the case of relatively stable conditions (e.g., long-term sequelae of an acquired brain injury or stroke), the person may be able to direct the management of his or her funds indefinitely. On the other hand, in progressive conditions in which the individual’s cognitive and behavioral capacities will continue to diminish (e.g., dementia), the person may at some point become unable even to direct the management of his or her funds.

One consideration in determining whether an individual is capable of directing the management of funds is whether the person is capable of appointing a proxy decision maker. Research supports the idea that individuals with dementia, for example, retain the capacity to appoint a proxy to make certain types of decisions even when they have lost the capacity to make those decisions themselves (Kim and Appelbaum, 2006; Kim et al., 2011). Capacity to appoint a proxy to make decisions in a certain area, such as management of one’s funds, requires only a general understanding of the nature of the decisions being delegated and trust in someone else to make those decisions (Kim and Appelbaum, 2006). Consistent with the four abilities associated with decision-making capacity, the individual must understand what is at stake in appointing a financial proxy, appreciate how designating such a proxy will affect him or her, indicate a choice about appointing a proxy (or not) and who it should be, and explain the reasoning underlying the choice made (Kim and Appelbaum, 2006).

Even when a proxy has been identified, supported decision making, as discussed in Chapter 3, is one way to preserve an individual’s financial autonomy as long as possible or, in some cases, to develop or restore that autonomy. Supported decision making—“the process of providing support to people whose decision making ability is impaired to enable them to make their own decisions wherever possible” (Davidson et al., 2015)—is an important part of a continuum that ranges from independent to substitute decision making. For beneficiaries, supported decision making could entail appointment of a representative payee who receives and has ultimate control over the individual’s benefits but who engages the beneficiary in decisions about disbursement of the funds to the extent possible. Such an approach is consistent with SSA’s current practice as described in Chapter 2. Alternatively, beneficiaries could receive and have direct control over all or a portion of their benefit payments directly but under the supervision of someone who could assist them with tasks such as budgeting and creating reports to track spending. This approach is consistent with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA’s) supervised direct payment program, described in Chapter 2. Another supported decision-making model is the

Advisor Teller Money Manager intervention, a money management-based substance use treatment intervention, in which therapists assist individuals affected by substance use in budgeting their income by having them go to a therapist to access their funds (Rosen et al., 2008, 2010). The therapist helps the clients manage their money, learn to budget their funds, and work to allocate discretionary funds in ways that reinforce constructive activities and limit substance use.

For individuals with a range of disabilities, supported decision making provides the opportunity to receive the assistance they need and want in order to make decisions about their lives, including how their funds are allocated. It is an approach that highlights interdependence as a typical method of decision making—that is, it is rare that any person makes decisions completely independently (United Nations, 2007). Supported decision making allows individuals who need assistance in managing their funds to decide whether they want to participate actively in decision making related to that process and if they do, to provide input on the types of supports they need and prefer.

Unless someone is appointed to assist them, individuals who are able to direct the management of their funds but require assistance in carrying out financial tasks because of physical or cognitive impairments will need to identify an appropriate person or entity to help them. If they cannot locate appropriate third-party assistance, they will be unable to perform financially in the real world even though they are competent to direct the management of their funds. This scenario illustrates one way in which contextual factors—in this case the absence of someone to assist the individual in managing his or her funds—can affect real-world financial performance and why it is important to take such variables into account when assessing an individual’s financial capability, as discussed in the following section.

FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE

Performance denotes the actual execution of actions situated in specific contexts and environments (Fisher and Griswold, 2014). How one carries out activities may be learned and developed over time or may be the result of novel or immediate circumstances. Financial performance is affected by factors from several domains, such as financial knowledge, behavior (what a person does with that knowledge), outside influences (factors that contribute to the person’s beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors, as well as external supports and barriers), and access (availability and use of appropriate financial products and services) (Sherraden, 2013). Contextual factors can affect an individual’s financial performance in the real world negatively or positively. As discussed earlier, individuals who clearly possess financial competence (knowledge and judgment) in a controlled setting (i.e., clearly

possess the requisite financial knowledge and conceptual, procedural, and judgment skills to manage their finances successfully) nevertheless may not perform well financially when, for example, they are subjected to real-world temptations (e.g., substance use, addiction disorders, impulse purchases, easy credit). Conversely, individuals with impaired financial knowledge or judgment may perform quite successfully if they have supports in place.

The ICF (WHO, 2001, p. 8) conceives of functioning and disability “as a dynamic interaction between health conditions and contextual factors,” which include personal and environmental factors. Personal factors are features of an individual that may affect his or her functioning, such as gender, age, social background, education, and past and current experience (WHO, 2001, p. 17). Environmental factors are factors external to individuals that “make up the physical, social, and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their lives” (WHO, 2001, p. 16). They include one-time or repeated stressors, social supports, financial and emotional resources, opportunities, and barriers.

Personal Factors

An example of personal factors that affect individuals’ financial performance is substance abuse. It impacts financial performance and well-being in a number of ways, including impaired decision making (Bickel et al., 1999; Black and Rosen, 2011; Coffey et al., 2003; Kirby and Petry, 2004; Petry, 2001), increased likelihood of being victimized (Claycomb et al., 2013), failure to maintain stable housing (Drake et al., 1993; Goldfinger et al., 1999; Lipton et al., 2000; North et al., 1998), worsening of psychiatric symptoms and increased risk of hospitalization (Grossman et al., 1997; Rosen et al., 2002; Shaner et al., 1995), and use of benefits to purchase the substances themselves.

Another personal factor that may affect financial performance is one’s mental state. Severe depression, for example, may not compromise one’s financial competence but may negatively affect one’s financial performance. It is important also to take into account fluctuating and fluid capacities and contexts (Lazar et al., 2015a), particularly for those with mental illnesses, as their symptoms, and hence their financial performance, may not remain stable. Changes in medication, medication adherence, and environmental stressors, for example, may alter one’s ability to control impulses, manage anxiety, and resist external pressures (Moye et al., 2005).

Religion is another personal factor that may affect decisions about saving and spending money and shape one’s ideas about the meaning of money and one’s approach to financial management. For example, religious doctrine and thought may emphasize the collective rather than the individual, thus affecting views about the balance of obligations toward oneself and

others; specify obligatory family rituals and gift giving; determine one’s approach to credit and loans; and so forth (Falicov, 2001). Tithing (i.e., donating a percentage of one’s income) to a faith community, for instance, is for some people an important means of fulfilling a religious duty, expressing gratitude, investing in a faith, and promoting social justice and charity. These contributions can constitute a relatively high percentage of one’s income (Marks et al., 2009), and thus may alter one’s material well-being and entail sacrifices. Religious affiliations and values can lead someone with low income to spend money in ways that may not appear “sound” because they do not always contribute to that individual’s financial or material well-being. Unlike other forms of “unsound” spending, however, these expenditures may be intentional, and involve trade-offs that impact spiritual well-being and religious beliefs in a fashion the person deems worthwhile.

Environmental Factors

A number of environmental factors affect not only financial performance but also financial competence. One such factor is socioeconomic status (SES)—a measure of a person’s economic and social position in society that is based on wealth, income, education, and occupation (Capuano and Ramsay, 2011; Kehiaian, 2012). SES impacts the opportunity to gain and demonstrate financial knowledge, skills, and behavior, as well as access to financial products and services and resources and opportunities. Worldwide, financial literacy (i.e., knowledge, skills, attitudes, and motivation) is low, and households with low SES demonstrate even lower financial literacy than those with higher SES (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011). People living in low-income communities typically have less opportunity than their higher-income counterparts to access effective financial instruments (e.g., affordable loans, bank accounts, interest-bearing savings, certificates of deposit) and to gain knowledge of successful financial management principles (i.e., maximizing gains and minimizing losses) (Sherraden, 2013). Conditions of poverty limit people’s opportunities to gain knowledge, skills, and behaviors that lead to more effective financial management, such as paying bills on time (Hilgert et al., 2003), having a low-cost bank account (FDIC, 2014), and having emergency savings on hand (Brobeck, 2008).

Research suggests that people gain knowledge as they gain financial experience, and that observed behaviors of their family and friends and economic socialization, as well as resources in their environment, play an important role in shaping their financial knowledge and behaviors (Hilgert et al., 2003; Payne et al., 2014; Sherraden, 2013). People with low income are at a disadvantage in this regard. Many low-income communities, for example, lack convenient access to banks as a result of the consolidation of the banking industry in the past several decades. Moreover, the incessant

difficulties resulting from scarce financial resources present cognitive challenges; occupy mental bandwidth; and leave people with less mental capacity for other aspects of everyday life, including some—such as avoiding high-interest loans and remembering to pay bills on time—that are central to successful financial performance (Mullainathan and Shafir, 2013).

People with low income are more likely than those with higher income to be unbanked (i.e., not have a bank account) or underbanked (i.e., have a bank account but also use alternative financial services) (Birkenmaier and Fu, 2015). The alternative financial services to which they tend to have convenient access (e.g., check cashing outlets, payday lenders), increasingly meet the needs of low-income communities for transaction and credit banking services, but at significantly higher costs than those of formal financial institutions (Prager, 2014; Stoesz, 2014).

Limited English proficiency, especially among immigrants to the United States, may further limit access to banks and other traditional financial institutions. Monolingual Spanish-speaking people with low income, in particular, have one of the highest unbanked rates in the nation (FDIC, 2014). Such unbanked households are particularly vulnerable to theft, loss, and debt, and face credit and financial security challenges that go beyond issues of individual financial capability (Morgan-Cross and Klawitter, 2011).

Culture also can affect financial performance. “Economic perspectives are produced through, and situated within, particular sociocultural contexts” (Carpenter-Song, 2012). Cultural understanding of what constitutes appropriate management of one’s funds is a product of variations in such factors as people’s perceptions of money and resources, locus of control, decision-making patterns, and help-seeking preferences, as well as access to financial knowledge and services. Values, habits, and beliefs concerning how to spend one’s money and how to use networks for support are culturally embedded. In some cultures, for example, it may be more important to give money as gifts than to spend money on oneself (Carpenter-Song, 2012). Given local cultural values and beliefs, it can be challenging to distinguish between “extravagance” and “wise spending” (Lazar et al., 2015b; Moye et al., 2005).

Such factors as access to formal bank accounts and financial products, networks of family and friends, the helpfulness of caregivers, opportunities offered by employers, life experiences, the stability and adequacy of living arrangements, real or perceived personal safety, and the quality of financial information available, acting individually or in interaction, can affect a person’s financial performance negatively or positively regardless of his or her level of financial competence. For example, people with little financial competence can exhibit positive financial performance with access to (1) helpful family members, friends, or caregivers who educate them about financial matters and help them take advantage of direct deposit of their

checks into a low-cost bank account at a formal financial institution (i.e., one that does not charge unreasonable fees for low balances and pays interest); (2) automatic bill paying for basic necessities (e.g., rent, utilities); and (3) a no-fee prepaid debit card with consumer protections to pay for other necessities, such as food. Other salient environmental factors include a stable living environment, experiencing little to no victimization, and few unexpected events that increase expenses and alter one’s financial situation. In a study of spouse-carers and individuals with dementia, for example, Boyle (2013) found social factors to be highly important to individuals’ financial performance. Those with borderline or diminished capacities could continue participating in making purchases and being engaged in the community given “practical strategies instigated by spouse-carers, such as arranging for purchases to be made on credit” (p. 560). Boyle (2008, 2013) also discusses “assisted autonomy”—strategies that enable people with dementia to utilize their extant capacity and exercise agency. This research highlights the importance of taking noncognitive factors, such as social and emotional supports, into account when assessing and facilitating the financial performance of people with dementia.

Conversely, a person with financial competence may exhibit poor financial performance if he or she (1) receives income through cash or a prepaid card with fees and few or no consumer protections; (2) lacks access to family members, friends, or caregivers who assist with helpful financial information; (3) lacks access to automatic bill paying; (4) lacks access to low-cost, convenient, beneficial financial products and services from a formal financial institution; and (5) lives in a community with conveniently accessed, higher-cost alternative financial services (e.g., check cashers, payday loan stores, auto title companies). The financial performance of a financially competent person also may be negatively affected by residential instability, victimization, and other life experiences (such as a health crisis or loved ones who need cash for their emergencies). Evidence suggests that individuals with the ability to manage their finances may, precisely in contexts of scarcity when careful financial management is critical, show performance difficulties in carrying out those tasks (Shafir, 2015). Emerging literature indicates that the everyday stresses of poverty can make it difficult for people to manage their insufficient resources, avoid highly needed (and often predatory) loans, and resist what may feel like urgent expenditures (Mullainathan and Shafir, 2013).

The Importance of Context

The foregoing discussion makes clear that financial performance is not related solely to an individual’s financial competence, but also is affected by the person’s context. With supports, individuals with seemingly diminished

capacity or judgment may be able to manage their finances effectively. Research in behavioral economics has documented many instances in which small changes in context (e.g., in defaults, in the framing of a problem, in perceived norms) can significantly alter performance (Mullainathan and Shafir, 2013).

To summarize, several types of abilities, including cognitive, perceptual, affective, communicative, and interpersonal, are required for a person to successfully handle the complex demands of managing his or her finances in the context of the challenges, supports, and resources found in his or her environment. These abilities may manifest themselves differently at the levels of competence versus performance. Thus, the person may recognize the need to exercise patience, planning, and impulse control and may even show the requisite abilities in the context of cognitive evaluation in a clinical or laboratory setting, but show diminished financial performance when within an environment rife with fatigue, distraction, stress, and a wide array of temptations. Family and peers, for example, can in some instances provide support and sound advice and in others be a source of stress and bad influence. The abilities necessary to maneuver and succeed in the context of everyday obstacles constitute a level of performance for which a person’s competence provides only one ingredient. Conversely, successful performance reflects adequate financial competence (knowledge and judgment), as well as the ability to implement financial decisions in the real world—that is, the presence of sufficient cognitive, perceptual, affective, communicative, and interpersonal abilities to manage or direct others to manage one’s benefits. Financial performance is, therefore, the best indicator of financial capability. Figure 1-1 in Chapter 1 illustrates the primacy of evidence of financial performance in determining financial capability.

It is important to note that personal and environmental factors may change or fluctuate, thereby affecting an individual’s financial performance. For this reason, it is necessary not only to assess financial performance at a single point in time but also to assess it longitudinally to best estimate a person’s financial capability. In addition, interpretations of evidence regarding beneficiaries’ financial performance can be informed by evidence of their degree of financial competence.

The committee recognizes that there will be cases in which evidence of real-world financial performance is very limited or unavailable. This may be the case, for example, when the person has had no funds to manage or when no third-party informant with knowledge of the person’s performance can be identified. In such cases, evidence of financial competence may be necessary to inform capability determinations. Evidence of financial (in)competence also can help to corroborate, refute, or explain evidence acquired regarding beneficiaries’ financial performance.

PREFERENCE FOR PERFORMANCE IN DETERMINING CAPABILITY

The preference for financial performance in determining financial capability is consistent both with the movement toward conceptualizing disability in terms of the interaction between individuals’ environment and their functional capacity (IOM, 1991, 1997, 2007; WHO, 2001) and with the reform of guardianship laws in the 1990s (Sabatino and Basinger, 2000).

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Framework

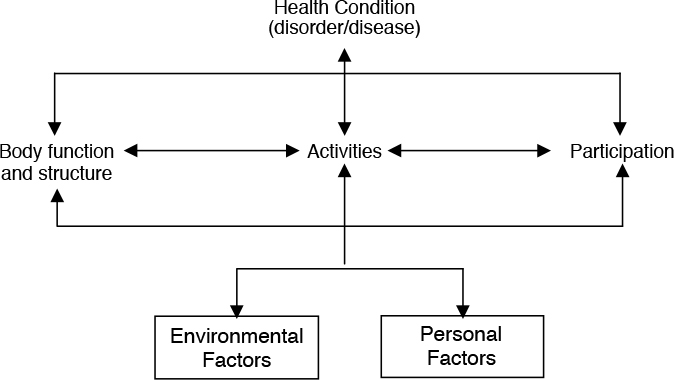

In 2001, WHO released the ICF (WHO, 2001), which was developed through a global consensus-building process. The ICF framework (see Figure 4-1) is similar to the conceptual framework used in this report to understand the concept of financial incapability.

The ICF framework portrays decrements in human functioning as the product of a dynamic interaction among various health conditions, incapacity to perform specific tasks and actions, and environmental and personal contextual factors that affect human behavior in a real-world context. The ICF component that corresponds most closely to the committee’s conceptualization of impaired financial performance is participation

SOURCE: WHO, 2001, p. 18.

restriction, defined as “problems an individual may experience in involvement in life situations” (WHO, 2001, p. 10). Restriction is explained as the “discordance between the observed and expected performance,” where expected performance refers to a “population norm” or standard based on the “experience of people without the specific health condition” (p. 15). Performance is described as “what an individual does in his or her current environment.” This is in contrast to the ICF concept of activity limitation, which denotes limits on a person’s ability to execute a task or action—similar to the committee’s concept of financial competence.

The ICF framework includes the concept of a health condition, a general term for a disease, disorder, injury, trauma, congenital anomaly, or genetic characteristic, the starting point for subsequent development of activity limitation and/or participation restriction (WHO, 2001). As with the conceptual model for the present report, the ICF includes environmental and personal factors as mediating contextual elements. Environmental factors are “all aspects of the external or extrinsic world” that form “the physical, social, and attitudinal circumstances in which people live and conduct their lives” (WHO, 2001, pp. 10, 213). Personal factors include gender, race, age, coping styles, and other individual characteristics that are not classified in the ICF. These contextual factors may act as facilitators or barriers as they affect a person’s activity or participation, much as contextual factors, such as those described in the previous section, can influence a person’s financial performance.

Reforms in Guardianship Law

Guardianship law specifies criteria for a legal determination that an individual is unable to make decisions about his or her person or property and that the state may therefore limit the person’s autonomy and appoint a guardian to protect his or her interests. The criteria for establishing legal incapacity are subject to change based on the “prevailing values, knowledge, and even the economic and political spirit of the time” (Sabatino and Basinger, 2000, p. 121). In the United States, guardianship laws and the criteria they embody have evolved over time. The early laws established determinations based on labels (e.g., “lunatic,” “person of unsound mind”) or behavior (e.g., excessive drinking, gambling, debauchery). Over time, most states adopted a medical approach that included requiring the presence of one or more disabling conditions, often specifying that the conditions “must result in a functional impairment with respect to one’s ability to manage his or her property or person” (Sabatino and Basinger, 2000, p. 123). Gradually, states began to replace that type of broad functional behavior test first with a more specific criterion focused on one’s ability to meet essential needs, such as food, shelter, and safety, and later with a cognitive functioning test. In addition, some states dropped the disabling condition requirement. Although

the 1982 Uniform Guardianship and Protective Proceedings Act retained the disabling condition requirement, it included a test of cognitive functioning. In 1997, the act was revised to remove the disabling condition requirement and incorporate an essential needs standard into the test of cognitive functioning (Sabatino and Basinger, 2000, pp. 126-127):

“Incapacitated person” means an individual who, for reasons other than being a minor, is unable to receive and evaluate information or make or communicate decisions to such an extent that the individual lacks the ability to meet essential requirements for physical health, safety, or self-care, even with appropriate technological assistance. (National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, 1997, sec. 102)

The committee’s preference for a performance-based standard for making determinations of financial capability is consistent with the movement in U.S. guardianship law away from a standard focused on an individual’s medical condition to one focused on a person’s functional ability to meet basic needs. It also is consistent with the ICF framework, which emphasizes real-world functioning (performance) that stems from a complex interplay among an individual’s health conditions, abilities (competence), and contextual factors. Both the evolution of guardianship law and the development of the ICF provide context and support for the committee’s emphasis on financial performance in capability determinations.

MENTAL AND PHYSICAL DISORDERS THAT MAY AFFECT FINANCIAL CAPABILITY

SSA asked the committee to identify specific mental and physical disorders, such as those in SSA’s Listing of Impairments for adults [Part A] (SSA, n.d.-b) or in SSA’s adult Compassionate Allowances templates (SSA, n.d.-a), that by definition preclude capability or that strongly indicate incapability. SSA also requested that the committee identify any mental or physical disorders for which the determination of capability could be made based solely on objective medical evidence.6 While believing that the best

___________________

6 In SSA terms, objective medical evidence refers to medical signs and laboratory findings. Laboratory findings must be demonstrated through “medically acceptable laboratory diagnostic techniques,” among which SSA includes psychological tests (20 CFR § 404.1528). “Signs are anatomical, physiological, or psychological abnormalities which can be observed, apart from [self-reported symptoms]. Signs must be shown by medically acceptable clinical diagnostic techniques. Psychiatric signs are medically demonstrable phenomena that indicate specific psychological abnormalities, e.g., abnormalities of behavior, mood, thought, memory, orientation, development, or perception. They must also be shown by observable facts that can be medically described and evaluated” (20 CFR § 404.1528). “Laboratory findings are anatomical, physiological, or psychological phenomena which can be shown by the use of medically acceptable laboratory diagnostic techniques. Some of these diagnostic techniques

indicators of financial capability are actual knowledge of individuals’ functional performance in their everyday environments and their consistency7 in managing financial matters and making financial decisions that are in their self-interest, the committee appreciates the expediency of a list of mental and physical conditions that preclude capability or that strongly indicate incapability. For a variety of reasons, however, the committee notes that there exist only a very limited number of conditions whose presence can be the sole basis for a capability determination.

To qualify for disability benefits under the Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance program, an applicant must have a physical or mental impairment severe in nature and of such duration that the person is unable to participate in any substantial gainful activity (Wixon and Strand, 2013). A medically determinable physical or mental impairment or combination of impairments is considered severe “if it significantly limits an individual’s physical or mental abilities to do basic work activities” (SSA, 1996). SSA’s Listing of Impairments “describes, for each major body system, impairments considered severe enough to prevent an individual from doing any gainful activity” (SSA, n.d.-c). “Most of the listed impairments are permanent or expected to result in death, or the listing includes a specific statement of duration. For all other listings, the evidence must show that the impairment has lasted or is expected to last for a continuous period of at least 12 months” (SSA, n.d.-c). The Listing of Impairments is organized by major body system and contains criteria for evaluating the severity of a listed impairment. These criteria may include assessments of work-related functioning8 and are designed to identify individuals with impairments that are sufficiently severe to prohibit them from engaging in any kind of “gainful activity” (SSA, n.d.-c). In some cases, an individual has multiple impairments, none of which is, by itself, sufficiently severe to meet the Listing criteria, or an impairment that is not included in the Listing. In such cases, the examiner considers whether the impairment or combination of impairments is medically equal to a listed impairment. If an otherwise qualified applicant’s impairment(s) meets or equals the Listing criteria, the claim is allowed.9

SSA recognizes that some conditions are so severe that they obviously meet its disability standards. The Compassionate Allowances initiative

___________________

include chemical tests, electrophysiological studies (electrocardiogram, electroencephalogram, etc.), roentgenological studies (X-rays), and psychological tests” (20 CFR § 404.1528).

7Consistency in this context means the individual behaves in a manner that adheres to the same or similar principles and intentions across time and situations.

8 For mental disorders, functional limitations are used to assess the severity of the impairment. Paragraph B and C criteria in the Listing of Impairments for mental disorders describe the areas of function that are considered necessary for work (SSA, n.d.-d).

9 All remaining applications move on to the next step in the disability evaluation process.

allows SSA to quickly identify applicants who invariably will qualify for disability benefits under the Listing of Impairments based on objective medical information that it can obtain quickly (SSA, n.d.-a).

In the following section, the committee discusses mental disorders and physical conditions that affect individuals’ cognitive and behavioral capacities and considers whether any of them would categorically preclude financial capability or strongly indicate incapability. In the subsequent section, the committee considers the same questions with respect to physical disorders that do not directly affect an individual’s cognitive capacity.

Disorders with Cognitive Effects

Evaluation of financial capability is important in individuals who have disorders that are severe enough to lead to work-related disability and negatively affect the cognitive domains relevant to financial competence discussed earlier—namely, general cognitive/intellectual ability, attention and vigilance, learning and memory, executive function, social cognition, and language and communication. Although the presence of such disorders raises the need for assessment of financial capability, their diagnosis alone ordinarily is not sufficient for making a capability determination. One difficulty is the variable impact of disorders on the individuals affected; another is the lack of correlation in many cases between the severity of one’s clinical symptoms and one’s functional limitations.

SSA’s evaluation of disability on the basis of mental disorders requires not only documentation of a medically determinable impairment(s) but also consideration of the degree of limitation imposed by the impairment(s) on the applicant’s ability to work, as well as whether these limitations have lasted or are expected to last for a continuous period of at least 12 months (SSA, n.d.-d). SSA’s Listing of Impairments for adults, Section 12.00, “Mental Disorders,” is arranged in nine diagnostic categories: organic mental disorders (12.02); schizophrenic, paranoid, and other psychotic disorders (12.03); affective disorders (12.04); intellectual disability (12.05); anxiety-related disorders (12.06); somatoform disorders (12.07); personality disorders (12.08); substance addiction disorders (12.09); and autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders (12.10).

For most of the diagnostic categories,10 adult applicants will meet a listing if the impairment satisfies the following: (1) the diagnostic description

___________________

10 The structure of the listings for intellectual disability and for substance addiction disorders differs from that of the other mental disorder listings. There are four sets of criteria (Paragraphs A through D) for the intellectual disability listing, and the listing for substance addiction disorders refers to which of the other listings should be used to evaluate the various physical or behavioral changes related to the disorder.

of the mental disorder; (2) specified medical findings—e.g., symptoms (self-report), signs (medically demonstrable), laboratory findings (including psychological test findings)—(Paragraph A criteria); and (3) specified “impairment-related functional limitations that are incompatible with the ability to do any gainful activity” (Paragraph B or Paragraph C criteria) (SSA, n.d.-d). Paragraph A criteria, in conjunction with the diagnostic description, substantiate the presence of the specific mental disorder based on the medical evidence. Paragraph B and Paragraph C criteria list the functional limitations resulting from the mental impairment that preclude the ability to engage in gainful activity. (IOM, 2015, p. 53)11

Many of the conditions that fall into these mental disorder diagnostic categories raise concern about an individual’s ability to manage his or her finances. Other conditions also may cause symptoms that include cognitive effects. For example, disorders associated with severe, unremitting pain (e.g., cancer metastatic to the bones), extreme debilitation (e.g., metastatic cancer, advanced heart failure), hypoxia (e.g., severe obstructive lung disease), and endocrine and metabolic imbalances (e.g., thyrotoxicosis, Addison’s disease, hyponatremia, hyperparathyroidism), as well as certain neurological conditions (e.g., Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease), can affect the capacities relevant to financial capability. The following sections address several broad types of disorders that may impair financial capability, including neurocognitive disorders, such as dementias; neurodevelopmental disorders; psychiatric disorders; substance-related disorders; and traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Neurocognitive Disorders

Neurocognitive disorders, which encompass SSA’s Listing 12.02 (organic mental disorders), include disorders of the brain, such as Alzheimer’s disease, diffuse Lewy body disease, frontotemporal dementia (e.g., Pick’s disease), vascular dementia, multiple system atrophy, and progressive supranuclear palsy, that are associated with cognitive decline (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In addition, some neurological disorders, such as Huntington’s disease or Parkinson’s disease, may progress to result in dementia and decline in cognitive domains. Individuals who are diagnosed with moderate or severe stages of these types of disease typically experience so many difficulties with cognitive function and orientation to time, place, and person, as well as with judgment, that they are unable to carry out many activities of daily living, including management of finances. They frequently require another person to help them with these activities and would be in danger without these supports. Furthermore,

___________________

11 This text has been modified from the prepublication version of the report.

most of these conditions are degenerative; that is, they are characterized by worsening over time. Studies of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease using the Financial Capacity Instrument (Griffith et al., 2003; Marson et al., 2000) indicate that impairment of financial competence appears first in mild cognitive impairment, is already widespread in people with mild Alzheimer’s disease, and is advanced and global in those with moderate levels of such disease (Griffith et al., 2003; Marson et al., 2000; Stoeckel et al., 2013; Triebel et al., 2009).

The Listing of Impairments takes account of the severity of applicants’ impairments with respect to their ability to perform gainful activity. Paragraph B criteria focus on functional limitations in four areas: (1) activities of daily living; (2) social functioning; (3) concentration, persistence, or pace; and (4) episodes of decompensation. To meet the Paragraph B criteria for organic mental disorders, the impairment as specified must result in at least two of the following: (1) marked restriction of activities of daily living; (2) marked difficulties in maintaining social functioning; (3) marked difficulties in maintaining concentration, persistence, or pace; or (4) repeated episodes of decompensation, each of extended duration (SSA, n.d.-e). “Marked” means more than moderate but less than extreme. A marked limitation is one in which “the degree of limitation is such as to interfere seriously with [one’s] ability to function independently, appropriately, effectively, and on a sustained basis (SSA, n.d.-d; see also §§ 404.1520a and 416.920a). Although someone who qualified for disability by meeting the Listing criteria for organic mental disorder might be incapable of managing or directing the management of his or her finances, the disability determination process focuses on individuals’ work-related impairment for the purpose of determining whether they qualify to receive benefits. The impairment threshold for determining disability may reasonably differ from that required to justify interference with beneficiaries’ autonomy with respect to management of their disability payment. As discussed in Chapter 3, the decision to appoint a representative payee must entail weighing the beneficiary’s personal autonomy and preferences against interventions that, while infringing on the beneficiary’s autonomy, are meant to protect his or her best interests. Deeming an adult to be incapable when he or she is not erodes personal liberty, establishes stigma through labeling, leaves the individual open to exploitation, and deprives the person of the freedom to direct personally appropriate actions based on long-held values and preferences. It therefore is reasonable to require a higher threshold of cognitive impairment for capability determination than for disability determination. For this reason, it would be imprudent to attempt to map the level of impairment associated with financial incompetence onto the level of impairment for work-related disability contained in the Listing of Impairments.

There are other difficulties as well with relying solely on diagnosis and medical evidence in making determinations of financial capability. One is the variable impact of disorders on the individuals affected; as noted earlier, different people experience and respond to medical conditions differently. Another is the lack of correlation in many cases between the severity of one’s clinical symptoms and one’s functional limitations. In addition, people may experience variations in their symptoms over time—especially earlier in the course of the illness—such as the fluctuations in cognition, either above or below baseline, that have been observed in people with different types of dementia (Lee et al., 2012). Fluctuations reflecting improved function have been associated with the legal concept of the lucid interval, which refers to a discrete, temporary period of time during which an otherwise incompetent individual is found to have the requisite capacity to execute a valid will (Shulman et al., 2015). However, the developing medical literature on cognitive fluctuation raises questions about the validity of the concept of a lucid interval (Shulman et al., 2015). Specifically, the fluctuations often are of short duration (i.e., seconds or minutes) and are relatively minor (e.g., an improvement over the person’s current baseline rather than to his or her predisease state of lucidity). In addition, the fluctuations affect primarily alertness and attention rather than memory and executive function, which are also important for financial competence (Shulman et al., 2015). At the same time, it should be noted that the nature of these fluctuations differs among types of dementia. In particular, studies have found fluctuations reflecting decrements in cognition in dementia with Lewy bodies to be associated primarily with decreased awareness and attention, while in Alzheimer’s dementia they are associated more with impaired memory (Bradshaw et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2012). Also, the fluctuations in the former condition appear to be more frequent, shorter in duration, and more intense than those observed in the latter (Bradshaw et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2012). In contrast to fluctuating cognition in Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive fluctuations in dementia with Lewy bodies often reflect transient decrements in function, followed by return to a near-normal level of cognitive function (Bradshaw et al., 2004), suggesting that such individuals may retain their financial capability some or most of the time even if they experience transient periods of financial incompetence. Finally, as previously discussed, contextual factors also may support continued successful financial performance in individuals experiencing a level of cognitive impairment sufficient to qualify for SSA disability benefits.

For all of these reasons, diagnosis and medical evidence of impairment alone constitute an insufficient basis for making determinations of financial capability in all but the most severe cases. It is important to note, however, that given the progressive nature of dementias, once an individual with dementia is no longer able to manage or direct the management of his or

her finances, the expectation is that the ability to do so will not return. Similarly, individuals with dementia who are still able to manage or direct the management of their finances are expected to lose that ability as their condition progresses and will need to be reevaluated on a regular basis.

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

The presence of neurodevelopmental disorders such as intellectual disability (Listing 12.05) and autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders (Listing 12.10) also signals the need to evaluate individuals’ financial capability. As noted in Chapter 1, SSA generally presumes that adult beneficiaries are financially capable absent evidence to the contrary. One exception is beneficiaries who meet mental disorder listing for intellectual disability 12.05A or 12.05B (SSA, n.d.-f). Individuals who qualify for disability under 12.05A demonstrate “mental incapacity evidenced by dependence upon others for personal needs (e.g., toileting, eating, dressing, or bathing) and inability to follow directions, such that the use of standardized measures of intellectual functioning is precluded.” Individuals who qualify for disability under 12.05B are those who possess “a valid verbal, performance, or full scale IQ [intelligence quotient] of 59 or less” (SSA, n.d.-f).

It appears clear that individuals who are sufficiently intellectually impaired so as not to be testable using standardized measures of intellectual functioning will also be financially incapable and will require a representative payee. The situation with respect to individuals who have a valid verbal, performance, or full-scale IQ of 59 or less is more complicated.

A small study of individuals with a mean full-scale IQ of 59 (range 50-67) showed performance on a temporal discounting task and a financial decision-making task to be related more strongly to executive functioning than to IQ (Willner et al., 2010a). In the first task, participants were asked to make a series of choices between smaller, more immediate rewards and larger, delayed rewards. The second task presented a series of increasingly complex scenarios in which a choice had to be made. For each scenario, the participants were asked a series of questions to elucidate their performance on five aspects of decision making (identification, understanding, reasoning, appreciation, and communication). Decision making on both tasks (temporal decision making and financial decision making) was based primarily on a single class of information (e.g., delay in reward, amount of reward) rather than a weighing of multiple pieces of information. This suggests that weighing different pieces of information for the purpose of decision making may be problematic for individuals with the participants’ level of intellectual disability. However, the association between difficulties with weighing multiple sources of information and executive function

rather than IQ suggests the possible benefit of psychoeducational strategies in improving decision making (Willner et al., 2010a). It also supports the view that functional assessment of financial performance is a better indicator of financial capability than IQ alone. A study of participants with a mean full-scale IQ of less than 70 (standard deviation [SD] = 5.4) generated similar results. That study found performance on a temporal discounting task among individuals with intellectual disability to be random, and when respondents’ choices were nonrandom (i.e., consistent), they displayed impulsivity. The study also showed that training improved the consistency of decision making among participants and that both initial and post-training performance were related to executive functioning rather than to IQ (Willner et al., 2010b).

The same group also looked at basic financial knowledge (versus understanding or functional ability) in participants with a mean full-scale IQ of 59.1 (SD = 5.1) (Willner et al., 2011). The test comprised a coin recognition task and a cost identification task (estimating the cost of certain items). Most participants identified all of the coins and the cost of an ice cream, but identification of costs for other, more expensive, items was poor. The total scores were significantly correlated “with receptive language ability and performance on memory tests but not with IQ or executive functioning” (Willner et al., 2011, p. 285).