A UNIFYING FRAMEWORK

Based on its review of the literature and multiple calls for action, the committee concludes that there is a need and a demand for a holistic, consistent, coherent structure that aligns education, health, and other sectors to better meet local needs in partnership with communities. This conclusion informed the committee’s vision for inspiring health professionals to engage in action on the social determinants of health while providing an educational structure for understanding a systems-based approach for such action.

Elements of a Unifying Framework

Chapter 3 presents a number of prior frameworks salient to understanding and acting on the social determinants of health. Each has particular strengths that, when combined, fulfill the committee’s vision for better aligning different sectors in educating health professionals to address the social determinants of health in partnership with communities. Overlaying this vision are Frenk and colleagues’ (2010) proposed instructional and institutional reforms for achieving “transformative and interdependent professional education for equity in health” (p. 1953). The actions taken to produce enlightened change agents who are innovative, adaptive, and responsive to the needs of the community is what these authors identify as “transformative learning.”1 Transformative learning, dynamic partnerships, and lifelong learning are fundamental principles underpinning the committee’s framework.

Transformative Learning

Transformative learning is key to addressing the social determinants of health. It involves vital shifts that would move health professional education from a traditional biomedical-centric approach to an approach that can provide a greater understanding of and competencies in addressing complex health systems in an increasingly global and interconnected world. Building upon the work of the Lancet Commission (Frenk et al., 2010), described in Chapter 1, the committee proposes a list of desired education outcomes from transformative learning that include competency to

- search, analyze, and synthesize information for decision making;

- collaborate and partner effectively with others;

___________________

1 For the purposes of this report, the terms “transformative learning” and “transformative education” are considered interchangeable.

- work with, understand, and value the vital role of all players within health systems and other sectors that impact health; and

- apply global efforts addressing health inequities to local priorities and actions.

Dynamic Partnerships

Dynamic partnerships also are key to effectively addressing the social determinants of health. These partnerships entail close working relationships among policy makers, educators, health professionals, community organizations, nonhealth professionals, and community members. Health professionals who are educated under what Frenk and colleagues (2010) term the “traditional model” of education—which focuses more on what is taught and by whom rather than on building relevant competencies—are unlikely to experience the exposure to the broader social, political, and environmental contexts provided by education from a wide array of partners. And innovative methods of education challenge learners to solve problems and make new connections through exposure to other professions, sectors, and populations. The bidirectional linkages formed between communities and educators reinforce equality in the partnership, which can be strengthened through mutual support among communities, educators, and organizations (Tan et al., 2013).

Lifelong Learning

The European Council Resolution on Lifelong Learning (Council of the European Union, 2002) describes lifelong learning as a continuum of learning throughout the life course aimed at “improving knowledge, skills and competences within a personal, civic, social and/or employment-related perspective” (p. C163/2). It involves formal education as well as nonformal and informal learning opportunities, as defined in a 2015 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) report (Yang, 2015). That report describes how lifelong learning, through the development and recognition of learners’ knowledge, skills, and competences, is gaining relevance for poverty reduction, job creation, employment, and social inclusion, all of which represent potential impacts on the social determinants of health.

As part of lifelong learning, nonformal education and informal learning opportunities create space for university–community partnerships to address the social determinants of health. Men’s Sheds, for example, are community-based organizations that began in Australia and have expanded around the world to offer older men a place to use, develop, and share such skills as furniture making (Wilson and Cordier, 2013). Health and social

policy makers use these venues to engage men and promote health and well-being outside of traditional health and care settings (Wilson and Cordier, 2013). Wilson and Cordier propose incorporating the social determinants of health and well-being in study designs to better analyze the health impacts of informal learning in Men’s Sheds. For the health professions, continuing professional development/continuing education and problem-based learning are often regarded as approaches to lifelong learning (FIP, 2014; Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, 2010; Lane, 2008; Wood, 2003).

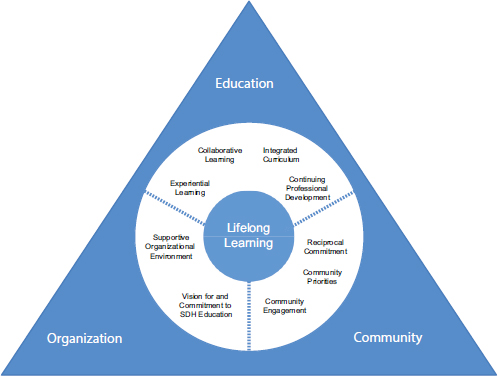

Domains of the Framework

Combining transformative learning, dynamic partnerships, and lifelong learning with key aspects of the frameworks presented in Chapter 3 (i.e., putting the community in charge, public health and systems context, health professional education and collaboration, and monitoring and evaluation), the committee developed a unifying framework for educating health professionals to address the social determinants of health (see Figure 4-1). For the

NOTE: SDH = social determinants of health.

impact of this framework to be fully realized, health professionals will need access to education that builds critical thinking through transformative learning opportunities, from foundational education through continuing professional development. Such education is built around three domains:

- education

- community

- organization

EDUCATION

The sorts of activities the committee believes serve as elements of transformative learning for addressing the social determinants of health go well beyond traditional lecturing. The committee views an approach to such transformative learning as involving creating, through education, highly competent professionals who understand and act on the social determinants of health in ways that advance communities and individuals toward greater health equity. Box 4-1 lists components of that education, which are discussed below.

Experiential Learning

Experiential learning is a vital component of education in how to apply understanding of the social determinants of health (Cené et al., 2010; McIntosh et al., 2008; McNeil et al., 2013). In 1984, Robert Kolb designed the Experiential Learning Cycle, which emphasizes that such education is effective only if learners are fully and openly involved in new experiences without bias and are provided time to reflect upon and observe their experience from many perspectives (Kolb, 1984). It is through experiential opportunities, combined with reflection, that learners develop and strengthen their competency for self-examination of personally held assumptions, values, and beliefs about individuals and populations. Exploration of one’s biases and positions needs to continue throughout life, reaching deeper levels as the health professional matures cognitively, personally, and professionally (El-Sayed and El-Sayed, 2014). Faculty and other educators similarly need to reflect upon their personal views, particularly with respect to the changing student population, which in some cases includes young people whose learning styles differ from those of prior generations and in other cases includes both more mature learners who bring substantial previous work experience and more entrants from overseas (Newman and Peile, 2002; Regan-Smith, 1998).

Applied Learning

Applied learning is a particular form of experiential learning that puts principles into practice through a mixed-methods pedagogical approach. It has a strong educational component that distinguishes it from volunteerism (Schwartzman and Henry, 2009). Given the lack of oversight and accountability in volunteer activities, the value to the community of purely altruistic activities by students and culturally unaware health professionals is suspect, and such activities may even be counterproductive (Caldron et al., 2015). An example of applied learning is service learning that places equal emphasis on service and on learning for the benefit of all parties involved (Furco, 1996).

Community Engagement

Strasser and colleagues (2015) explore relationships between communities and medical education programs. Such relationships have evolved from community-oriented activities in the 1960s and 1970s, to community-based interventions in the 1980s and 1990s, to the twenty-first-century concept of community-engaged education. Community engagement denotes service learning activities that stress reciprocity and interdependence in mutually

beneficial partnerships between academic institutions and the communities in which they reside (Furco, 1996; Sigmon, 1979).

Performance Assessment

Performance assessment of the competency of health professionals, students, and trainees in addressing the social determinants of health entails demonstrating competencies articulated for transformative learning. The expectations for such competencies in performance assessment deepen in complexity as learners mature and progress from foundational education to continuing professional development, and as their experiences with the social determinants of health broaden. The 360-degree multisource feedback model is one method used to garner a wide array of inputs for assessment of professionalism and teaching, as well as for program evaluation (Berk, 2009; Donnon et al., 2014; Richmond et al., 2011).

Collaborative Learning

There are a variety of approaches to collaborative learning (Dillenbourg, 1999). The unifying factor for all of these approaches is an emphasis on group work that involves students co-learning with each other, communities, and health professionals who also learn from each other (Dooly, 2008). In the field of public health, in which learners grow to understand how to address problems within complex systems, learning how to work collaboratively with other professions and other sectors is critical (Carman, 2015; Kickbusch, 2013; Levy et al., 2015; Lomazzi et al., 2016). But all health professionals are increasingly being called upon to work collaboratively with other professions. Engaging students through interprofessional projects in and with communities can help build the capacity of the health workforce for understanding and acting on the social determinants of health.

Problem/Project-Based Learning and Critical Thinking

Problem-based learning is generally viewed by students as beneficial and can promote a desire to learn (Barman et al., 2006; Cónsul-Giribet and Medina-Moya, 2014). Such learning provides opportunities to build competencies in communication, problem solving, teamwork, and collaboration involving mutual respect for others (Wood, 2003). With this pedagogy, learners develop critical thinking skills through learner-centered approaches that reflect real world situations (Ivicek et al., 2011; Shreeve, 2008).

Problem/Project-Based Learning and Student Engagement

At McMaster University, where problem-based learning originated, students are presented with individually designed problems to stimulate and guide their learning. Each problem varies with regard to group sizes and the incorporation of other pedagogy, but each follows a similar process that requires active student engagement through self-study and guidance by educators who establish clear learning objectives for the activity (Walsh, 2005). Problem-based learning has shown positive impacts on critical thinking and movement toward lifelong learning; given the self-directed nature of the activity, however, obtaining its full benefit requires diligence in maintaining the processes involved (Khoiriyah et al., 2015).

Project-based learning is an adaptation of problem-based learning whereby students are challenged to confront real situations so as to acquire a deeper understanding of such situations (Edutopia, 2016; Thomas, 2000). As such, project-based learning can be considered a useful tool for educating health professionals in addressing the social determinants of health in and with communities.

Integrated Curriculum

Multiple perspectives on what constitutes an integrated curriculum have led to varying definitions of the term (Brauer and Ferguson, 2015; Howard et al., 2009; Pearson and Hubball, 2012). Broadening Brauer and Ferguson’s (2015) proposed definition of the term for medical education, the committee considers it to mean an interprofessional approach for delivery of information and experiences that combines basic and applied concepts throughout all years of foundational education.

Interprofessional and Cross-Sectoral2 Curriculum

The development of competencies to engage interprofessionally and across sectors in partnership with communities and community organizations is an important element of transformative learning for addressing the social determinants of health. Providing interprofessional opportunities presents logistical and social challenges (Anderson et al., 2010; Cashman et al., 2004) that are distinct from the challenges of community-engaged learning opportunities (Michener et al., 2012; Strasser et al., 2015). But as the service-learning home visitation program of Florida International

___________________

2 The committee envisions a health workforce that is proactive in addressing and acting on the social determinants of health, and therefore elected to take a cross-sectoral approach rather than the intersectoral approach taken by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Lancet Commission.

University and other such programs demonstrate, the potential gains that accrue from learning from and with other professions and other sectors can be powerful educational tools (Art et al., 2007; Bainbridge et al., 2014; Mihalynuk et al., 2007; Ross et al., 2014). In the case of the Florida International University program, medical, nursing, social work, and law students, plus faculty, work together in addressing patients’ nonhealth needs so as to improve their health. This interprofessional and cross-sectoral outreach to individual community members has resulted in greater adherence to preventive health measures and a tendency to make fewer trips to the emergency room compared with individual households that received minimal intervention (Rock et al., 2014). Some entire programs have been designed around transdisciplinary problem solving in public health, while in other cases, the overall educational strategy has been reshaped to promote competencies across fields through transformative learning and integrated instructional design methods (Frenk et al., 2015; Lawlor et al., 2015).

Longitudinally Organized Curriculum

Creating a longitudinal curriculum for the social determinants of health conveys to students the importance of the topic for their professional development (Doran et al., 2008), and allows learning objectives to build and increase in complexity as students advance in their professional development and maturity. In a review of the literature using the BEME (Best Evidence Medical and Health Professional Education) review guidelines, Thistlethwaite and colleagues (2013) found that for most medical students, longitudinal placements (including both community and hospital placements) varied in length from one half-day per week for 6 months to full-time immersion for more than 12 months. The University of Michigan Medical School organizes a required Poverty in Healthcare curriculum that runs throughout the 4 years of education (Doran et al., 2008).

Continuing Professional Development

Faculty Development

Faculty development is one way in which leadership and organizations can demonstrate their support for educators wishing to offer interprofessional, community-engaged learning. Possessing the skills to offer transformative learning opportunities is essential not only for university faculty but also for community volunteers and preceptors, who are often geographically dispersed, diverse in their backgrounds and experience, and challenged by intense time and resource pressures (Langlois and Thach, 2003). Langlois and Thach suggest practical strategies for overcoming

some of these barriers, such as offering “just in time” training, providing a variety of educational formats, and linking training to continuing education credits.

Toolkits for quality improvement of education in community facilities (Malik et al., 2007), workplace learning, and learning communities may offer additional strategies for skill and knowledge acquisition by university and community-based faculty and volunteers (Chou et al., 2014; Lloyd et al., 2014; O’Sullivan and Irby, 2011). On-site training that allows workers at understaffed organizations to remain at the workplace for training is a viable option, particularly for low-resource settings (Burnett et al., 2015).

Interprofessional Workplace Learning

According to Lloyd and colleagues (2014), learning in the workplace can be formal, as in the case of an invited speaker, or informal, as when peers come together spontaneously to reflect upon an incident. While some have proposed informal workplace learning as a method for interprofessional education, it remains a relatively untapped opportunity for sharing learning across professions (Kitto et al., 2014; Mulder et al., 2010; Nisbet et al., 2013). Making interprofessional workplace learning more integral to everyday practice is a way of supplying busy providers of health care and social support with real-time education and interactions with respect to how social, political, and economic conditions impact the health of individuals and populations. However, insufficient staffing and heavy workloads can impede even informal educational opportunities (Lloyd et al., 2014; Wahab et al., 2014). Leaders who are supported by their organizations can create space to encourage such interactions.

Recommendation

Introducing any of the components discussed above into health professional education would represent a move toward transformative learning, but for maximal impact, the committee makes the following recommendation:

Recommendation 1: Health professional educators should use the framework presented in this report as a guide for creating lifelong learners who appreciate the value of relationships and collaborations for understanding and addressing community-identified needs and for strengthening community assets.

Implementing the committee’s framework would enable health professional students, trainees, educators, practitioners, researchers, and policy makers to understand the social determinants of health. It also would

enable them to form appropriate partnerships for taking action on the social determinants of health by engaging in experiential learning that includes reflective observations; promoting collaborative, interprofessional, and cross-sectoral engagements for addressing the social determinants; and partnering with individuals and communities to address health inequities.

To demonstrate effective implementation of the framework, health professional educators should

- publish literature on analyses of and lessons learned from curricula that offer learning opportunities that are responsive to the evolving needs and assets of local communities; and

- document case studies of health professional advocacy using a health-in-all-policies approach.3

COMMUNITY

Partnerships with communities are an essential part of educating health professionals in the social determinants of health. The community becomes an equal partner in teaching health professionals, faculty, and students about its experiences and how the social determinants have shaped the lives of its members. In this way, community members educate health professionals about the priorities of the community in addressing disparities stemming from the social determinants of health. Through shifts in power from health professionals to community members and organizations, the community shares responsibility for developing strategies for the creation of learning opportunities that can advance health equity based on community priorities. Box 4-2 outlines the three identified domain components that are essential for partnerships with communities.

Reciprocal Commitment

To better understand the goals of service learning and community-based medical education, Hunt and colleagues (2011) conducted a systematic review of the literature. The authors report enthusiasm among educators for employing community-based education as a method for teaching the social determinants of health, but found little evidence that community members were routinely involved in identifying local health priorities. This situation is not unique to medicine. Taylor and Le Riche (2006) looked at the equality of partnerships between service users and carers in social work

___________________

3 “Health in all policies” denotes an approach to policies or reforms that is designed to achieve healthier communities by integrating public health actions with primary care and by pursuing healthy public policies across sectors (WHO, 2008a, 2011a).

education. They suggest that effective strategies are needed for “improving the quality of partnerships working in education, and health and social care practice” (p. 418). However, they also point out that research in this area is lacking, which influenced their findings. One positive finding came from a study of service-learning activities at Morehouse School of Medicine aimed at addressing health disparities among underserved youth and adults (Buckner et al., 2010). These authors define success as the commitment from community organizations to engage in activities with students for multiple years. According to Strasser and colleagues (2015), such reciprocal commitment between communities and universities involves open and level communication with community leaders and members so that assumptions can be challenged in an effort to understand the perspectives of all stakeholders (Strasser et al., 2015).

While service-learning projects and community-based education serve as an effective bridge between the classroom and the community, such programs often train students in how to educate communities instead of empowering communities to educate current and future health professionals. Learning how to educate and learning how to listen are equally important for health professionals, students, and trainees if they are to work effectively in and with communities.

Community Assets

An often-cited study by McKnight and Kretzmann (1990) identifies the “deficiency-oriented social service model” as a source for thinking of

low-income neighborhoods as needy rather than as resources for improving quality of life. The result is a needs assessment that identifies, quantifies, and maps problems faced by a community, such as a high crime rate, low literacy, and poor health outcomes. In contrast, mapping even the poorest community’s assets, capacities, and abilities places within the community the locus of control for building upon existing resources and incorporating new ones. Neighborhood asset mapping is used around the world for actively engaging communities on such topics as obesity (Economos and Irish-Hauser, 2007), diabetes (Kelley et al., 2005), mental health (Selamu et al., 2015), and chronic disease prevention (Santilli et al., 2011). For its chronic disease prevention activity, for example, the Yale School of Public Health employed local high school students to conduct asset mapping. By partnering with youth leadership development organizations, the Yale researchers gained valuable information about community assets while employing youth and gaining entry into what Santilli and colleagues (2011) describe as “some of New Haven’s most research-wary and skeptical neighborhoods” (p. 2209).

In 2005, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation supported development of the Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) Institute’s guide to mobilizing local assets and organizational capacity (Kretzmann et al., 2005). This guide identifies five categories of community assets (see Box 4-3). These categories can guide universities in characterizing community assets in order to strengthen stakeholder partnerships through community engagement.

Willingness to Engage

Community mistrust of academic institutions is an impediment to forming sustainable academic–community partnerships for addressing the social determinants of health that lead to health disparities (Abdulrahim et al., 2010; Christopher et al., 2008; Goldberg-Freeman et al., 2007; Jagosh et al., 2015). Given the history of exploitative research in disadvantaged communities, such mistrust is understandable, but it also impedes valuable research that could eliminate health disparities (Christopher et al., 2008).

Community-based participatory research is an approach to designing studies that builds and maintains community trust through equitable involvement of all partners in the research process (NIH OBSSR, n.d.). With this approach, community members and researchers work together to construct, analyze, interpret, and communicate the study findings. The combination of shared knowledge and a desire for action is the engine for social change that improves community health and reduces health disparities. Numerous groups around the world have used community-based participatory research to build community trust in research aimed at improving health, equity, and quality of life in communities (Abdulrahim et

al., 2010; Metzler et al., 2003; Mosavel et al., 2005; Teufel-Shone et al., 2006; Wallerstein and Duran, 2010).

Networks and Resources

Formal and informal networks provide resources for meeting the daily needs of communities (McLeroy et al., 2003). During the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, the church was frequently identified as a formal pathway to HIV prevention, treatment, and impact mitigation (Campbell et al., 2013a,b; Murray et al., 2011). Other formal networks include schools, businesses, voluntary agencies, and political structures. Within formal structures are informal social networks formed among families, neighborhoods, and populations that share unique characteristics. These informal support systems hold potential solutions to better meeting the needs of community members. However, researchers’ access to these less formal networks require an insider’s understanding of the community (McLeroy et al., 2003). Funneling resources through informal networks arguably strengthens researchers’ access to and collaborations with communities.

Community Priorities

Community-based research differs from community-based participatory research. The former indicates only the locus of the activity, whereas the latter empowers communities to engage fully with the research being undertaken in their community (Blumenthal, 2011). While community-based participatory research is an ethical approach that empowers communities, it does present some risk to the researcher when community priorities do not match those of the researcher or even involve health (Williams et al., 2009). Balancing community priorities with the interests and skill set of the academic researcher requires careful negotiation among all parties, including the organizations funding and supporting the work (Rhodes et al., 2010).

One way to ensure that research reflects community priorities while further enhancing the education of health professionals in the social determinants of health is by conducting health impact assessments (HIAs)—in depth examinations of policies, programs, or projects for their effects on population health (Bhatia et al., 2014; WHO European Centre for Health Policy, 1999). HIAs have been used worldwide within the context of a health-in-all-policies approach to explore potential unintended consequences of policies and initiatives for the health of populations or segments thereof (Collins and Koplan, 2009; Leppo et al., 2013). This cross-sector approach has been adopted by groups throughout the world to improve population health and health equity. With this approach, public policies are analyzed systematically for their potential effects on health determinants. The findings of such analyses can be used to hold policy makers accountable for the health impacts of policies they promote (Leppo et al., 2013). The University of Wisconsin Department of Population Health Sciences incorporated both service learning and HIAs in its master’s-level public health course to generate knowledge, as well as to build a foundation for community partnerships (Feder et al., 2013).

According to Heller and colleagues (2014), “the process of conducting an HIA can build or strengthen relationships between stakeholders and can engage and empower populations who are likely to be affected by a proposal and who may already face poor health outcomes and marginalization. HIAs often recognize the lived experience of those populations as important evidence” (p. 11054). The authors propose incorporating equity considerations into HIA practice so that impacts of policy and planning decisions on population subgroups can be traced and then used to empower marginalized communities so as to promote and protect health equity (Heller et al., 2014). To measure progress toward this goal, the authors developed equity metrics that comprise “a measurement scale, examples of high scoring activities, potential data sources, and example interview ques-

tions to gather data and guide evaluators on scoring each metric” (Heller et al., 2014, p. 11055). The health professions might consider these metrics for use in guiding the development of desired competencies for partnering with communities to address the social determinants of health.

Community Engagement

Increasing the representation of indigenous and minority populations in health professional education and practice is critical to addressing the social determinants of health that lead to health inequities (Curtis et al., 2012; LaVeist and Pierre, 2014). Identification of potential candidates for the health professions starts with secondary school recruitment, although efforts to build the pool of future candidates need to begin much earlier through community engagement activities (McKendall et al., 2014; Phillips and Malone, 2014; WHO, 2006). Curtis and colleagues (2012) describe the recruitment pipeline as beginning with early exposure of young students to health careers and enrichment activities that encourage academic achievement. Next is supporting students through transitions into and within health professional programs, as well as providing institutional, academic, and social assistance to retain students through graduation. Throughout the pipeline, professional workforce development that engages families and communities is particularly important during early exposure to career pathways. Across the entire pipeline are opportunities to involve communities, role models, and mentors in recruiting and retaining locally derived students and faculty from underrepresented communities to enhance workforce diversity and better address the needs and priorities of the communities they represent.

Workforce Diversity

In general, people stay within social networks that resemble their own sociodemographics (Freeman and Huang, 2014; McPherson et al., 2001). This tendency toward homophily results in homogeneous groups with similar backgrounds, cultures, attitudes, and opinions. Homophily has been shown to impact people’s choices of whom to marry and befriend, as well as whom health professionals interact with at work, who collaborates on scientific research and publication, and who is hired (Freeman and Huang, 2014; Mascia et al., 2015; Maume, 2011; McPherson et al., 2001). As a result of closed social and occupational networks, positions are reinforced rather than challenged, which leads to greater group harmony with lower performance gains (Freeman and Huang, 2014; Phillips et al., 2009). For example, publications have been found to have greater impact when produced by a more ethnically diverse research group rather

than a group with little to no diversity (Freeman and Huang, 2014). And exposure to multiple cultures correlates positively with enhanced creativity, provided individuals are open to other perspectives (Hoever et al., 2012; Leung et al., 2008).

Health professional schools are charged with the responsibility of preparing a competent health workforce that can meet the needs of a rapidly changing, racially and ethnically diverse population. Cultural competency training is a common strategy for creating a more culturally and linguistically competent health workforce (AHRQ, 2014). However, another, potentially more direct intervention is to recruit and retain faculty and health workers who reflect the cultural diversity of the community served (Anderson et al., 2003; Kreiner, 2009).

Recruitment and Retention

Having a diverse and inclusive faculty offers students and trainees of all backgrounds role models and mentors with life experiences and cultures similar to their own. However, recruiting and retaining minority and female faculty who themselves may feel unsupported can create barriers to achieving the desired mix of health professional educators, particularly in senior academic positions (Price et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2014; Whittaker et al., 2015). Phillips and Malone (2014) reviewed methods used to increase the racial and ethnic diversity in the nursing profession by recruiting and retaining underrepresented minority groups in undergraduate nursing programs. One of their recommendations is to establish “stronger linkages between nursing practice and the social determinants of health in nursing education and clinical practice” (p. 49). For increasing diversity in medicine, Nivet and Berlin (2014) recommend increasing the scope and effectiveness of pipeline programs to better ensure the success of minority and socioeconomically disadvantaged young people. They point to the successful Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Summer Medical and Dental Education Program, which cultivates local talent through personal as well as academic assistance (RWJF, 2011). Finally, as efforts are under way to assess and address the challenges to increasing the representation of minority students and faculty in the health professions, it is important to stress that successfully recruiting and sustaining a diverse academic workforce will require a shift in the institutional climate with respect to diversity (Butts et al., 2012; Price et al., 2009; Whittaker et al., 2015; Yager et al., 2007).

Recommendation

In reviewing the literature, the committee concluded that there remains a need for health professional schools and organizations to recruit

and admit viable candidates from the pool of eligible4 applicants who have been negatively affected by the social determinants of health. Equal emphasis on retaining these candidates once accepted into the program is essential. Candidates for student, trainee, and faculty positions will ideally be recruited from the local community and will represent the population to be served. In pursuit of this ideal, the committee puts forth the following recommendation:

Recommendation 2: To prepare health professionals to take action on the social determinants of health in, with, and across communities, health professional and educational associations and organizations at the global, regional, and national levels should apply the concepts embodied in the framework in partnering with communities to increase the inclusivity and diversity of the health professional student body and faculty.

To enable action on this recommendation, health professional education and training institutions should support pipelines to higher education in the health professions in underserved communities, thus expanding the pool of viable candidates who have themselves been negatively affected by the social determinants of health.

ORGANIZATION

The Cambridge Dictionary defines “organization” as “a group of people who work together in an organized way for a shared purpose” (Cambridge University Press, 2016). Applying this definition within the context of this report, organizations include but are not limited to universities, schools, religious establishments, governmental and nongovernmental organizations, businesses, hospitals, and clinics.

High-level organizations—those that typically possess funds, prestige, or both—are positioned to set the tone for local organizations that have more direct contact with communities. For example, the call to action by government leaders following the World Conference on Social Determinants of Health that led to the Rio Declaration guided member states such as Canada to take local action to influence and improve the working and living conditions that affect the health and well-being of its citizens (PHAC, 2014). Similarly, national recognition of the need for greater diversity in

___________________

4 The pool of eligible students starts with primary and secondary education to encourage a new generation of health workers who are at the pre-entry stage. It also includes adults who might enter the health workforce from other sectors, and current health workers looking to expand their knowledge or change their employment position.

nursing on the part of U.S. nursing organizations and government nursing divisions led to local initiatives focused on recruiting and retaining underrepresented minority groups in nursing education programs (Dapremont, 2012; Phillips and Malone, 2014).

Lessons learned from the work of Health Canada in promoting equity in the health sector point to the importance of a strong organizational culture for setting priorities to address the causes of disparities (PHAC, 2014). Key factors deemed necessary for initiating and sustaining action on activities addressing the social determinants of health include ethical, moral, and humanist commitments from leaders; well-resourced and -trained staff and partners; and supportive organizational environments (PHAC, 2014; Raphael et al., 2014) (see Box 4-4).

Vision for and Commitment to Education in the Social Determinants of Health

Health professional schools are part of the community they serve and have a unique opportunity to improve the community’s living and working conditions. For example, academic institutions that engage local organizations and community members in offering career pathways to the health professions send a clear message about their commitment to addressing the social determinants of health within their community. And while expanding the diversity of students and faculty in health professional schools is critical, such efforts will have limited impact unless the climate of the institution goes beyond one of diversity to one of inclusivity (Nivet and Berlin, 2014). A culture of inclusivity moves organizations and institutions closer to desired transformative learning environments.

Policies, Strategies, and Program Reviews

Integrating health equity into an organization’s policies, strategies, and program reviews represents a significant step toward an institutional commitment to addressing the underlying causes of social disadvantage and marginalization (PHAC, 2014; PMAC Secretariat, 2014; Redwood-Campbell et al., 2011). To this end, the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA’s) Division of Nursing required its 2013 funding applicants to incorporate the social determinants of health into proposed strategies aimed at diversifying the nursing workforce to improve population health equity (Williams et al., 2014). The funding requirements included developing relevant measures and metrics so programs can be reviewed for their progress toward decreasing health disparities and improving health equity.

Resources

Often through research and grant-funded projects, health professional schools bring to bear financial resources for building partnerships between university and community organizations. The University of British Columbia provides multiple examples of context-specific work undertaken in partnership with community organizations (UBC, n.d.). In these examples, each group contributes unique resources that support mutually agreed-upon goals that benefit all the organizations involved.

Infrastructure and Promotion/Career Pathways

Effective community engagement requires strong commitment from faculty. However, few academic institutions invest in the infrastructure that can enable faculty members to work in and with communities (DiGirolamo et al., 2012; Gelmon et al., 2012; Nokes et al., 2013).

In 2012, a university working group was asked to recommend organizational structures that would better support, enhance, and deepen community engagement and community-engaged scholarship at the university. While the group noted a strong university commitment to community engagement, the existing organizational structures did not enable action on that commitment (UMASS Boston, 2014). The group determined that establishing a coordinating infrastructure to bring different parties together would better enable sustainable partnerships. The group also looked at evaluation of and rewards for faculty working in and with communities. The group, like others, found that the university had insufficient policies to support community engagement as core academic work (Ladhani et al., 2013; Michener et al., 2012; UMASS Boston, 2014).

Direct involvement of university leadership in the development of guidelines for evaluating and rewarding community-engaged scholarship for tenure and promotion paths has been identified as a way of lowering barriers to greater community engagement in addressing the social determinants of health (Marrero et al., 2013). One example is the University of Minnesota, which recently revised its promotion and tenure guidelines to recognize community engagement (Jordan et al., 2012). Others are making similar strides in this area (AAMC, 2002; Bringle et al., 2006; Loyola University Chicago, 2016; UMASS Boston, 2014; USF, 2016). In addition, the need for faculty release time to create, maintain, and sustain equitable partnerships that sometimes take years to cultivate could be factored into tenure decisions (Calleson et al., 2002; Nokes et al., 2013; Seifer et al., 2012).

Supportive Organizational Environment

Academic institutions that support transformative learning environments take advantage of networking opportunities and partnerships for educating students, trainees, and health professionals (Frenk et al., 2010). Such an approach offers learners the opportunity to see and at times experience the world from another’s perspective. In addition, organizations that support experiential opportunities—a key part of transformative learning for addressing the social determinants of health—prepare students for work outside of the predictable environment of the university setting (Holland and Ramaley, 2008). Given the intractable nature of many older institutions of higher learning, small shifts toward transformative learning would represent large steps. More recently established health professional schools are arguably more malleable and have greater flexibility to support more proactive environments for transformative learning, and it would be beneficial to encourage them to do so.

Transformative Learning and Dissemination of Pedagogical Research

Understanding the comparative advantage of each organizational partner is a step toward developing a transformative approach to engagement that can advance both university and community goals (Holland and Ramaley, 2008). One study that examined the role of transformative learning in cross-profession partnerships between campus faculty and county extension educators identified key factors in the success of such learning (Franz, 2002). Among other findings, the author states that a climate of independence mixed with interdependence is important for cross-profession relationship building and partnership formation. The author also asserts that “models of successful staff partnerships need to be identified and lauded across the organization.” Communicating the value of transforma-

tive learning approaches for addressing the social determinants of health legitimizes interprofessional and cross-profession partnerships (Franz, 2002). Promoting and actively disseminating faculty research in this area by means of annual faculty reports, newsletters, and recognition of faculty excellence through chancellor’s awards for distinguished scholarship, teaching, and service can diffuse such messages more broadly within and outside of universities (UMASS Boston, 2014).

Faculty Development/Continuing Professional Development

Academic institutions often provide faculty some form of support for training in teaching and research, but few provide development opportunities for community-engaged faculty members (Jordan et al., 2012). One exception is the University of Massachusetts’ Civic Engagement Scholars Initiative within the university’s Office for Faculty Development. This program supports faculty and departments engaged in redesigning and evaluating courses in the development of effective methods for engaging students in service-learning and community-based research activities that “reinforce classroom learning, foster civic habits and skills, and address community-identified needs” (Martinez-Krawiec, 2013).

Faculty development has been used as a tool for organizations seeking to recruit and retain a diverse workforce (Daley et al., 2006). The Office of Faculty Development at Harvard Medical School, for example, offers a comprehensive program that includes specific activities and events targeted at women and underrepresented minority faculty. Similarly, the Minority Faculty Leadership and Career Development Program at Boston University’s Schools of Medicine and Public Health is a longitudinal leadership and career development program for underrepresented minority faculty (BUSM, 2015). Through self-reflection and assessment, experiential learning, and peer and senior mentorship, the program aims to provide faculty with tools to effect positive change throughout their careers.

Recommendation

The committee encourages organizations to build upon policies, strategies, programs, and structures already in place to transform learning environments such that they align with the framework presented in this report. A first step is to understand how the social determinants of health are reflected within the organization’s founding and guiding policies, strategies, programs, and structures. Therefore, in response to the calls for action from signatories of the Rio Declaration, as well as many individual health professionals and their representative professional and educational organizations, the committee makes the following recommendation:

Recommendation 3: Governments and individual ministries (e.g., signatories of the Rio Declaration), health professional and educational associations and organizations, and community groups should foster an enabling environment that supports and values the integration of the framework’s principles into their mission, culture, and work.

To accomplish this recommendation, national governments, individual ministries, and health professional and educational associations and organizations should review, map, and align their educational and professional vision, mission, and standards to include the social determinants of health as described in the framework. The following actions would demonstrate organizational support for enhancing competency for addressing the social determinants of health:

- Produce and effectively disseminate case studies and evaluations on the use of the framework, integrating lessons learned to build and strengthen work on health professional education in the social determinants of health.

- Work with relevant government bodies to support and promote health professional education in the social determinants of health by aligning policies, planning, and financing and investments.

- Introduce accreditation of health professional education where it does not exist and strengthen it where it does.

- Design and implement continuing professional development programs for faculty and teaching staff that promote health equity and are relevant to the evolving health and health care needs and priorities of local communities.

- Support experiential learning opportunities that are interprofessional and cross-sectoral and involve partnering with communities.

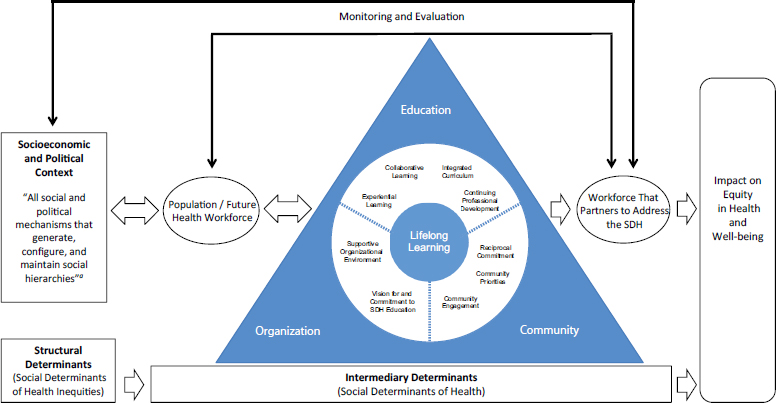

FITTING THE FRAMEWORK INTO A CONCEPTUAL MODEL

Anchoring the framework within a broader societal context can facilitate understanding and uptake of the framework. The committee’s conceptual model (see Figure 4-2) draws on multiple sources to show how strengthening health professional education to address the social determinants of health can produce a competent health workforce able to partner with communities and other sectors to improve the socioeconomic and political conditions that lead to health inequity and diminish health and well-being (Frenk et al., 2010; HHS, 2010; Solar and Irwin, 2010; Sousa et al., 2013; WHO, 2006, 2008b, 2011b).

At the left of the committee’s conceptual model is the socioeconomic and political context, broadly defined as including all social and political

NOTE: SDH = social determinants of health.

a Solar and Irwin, 2010, p. 5.

mechanisms that generate, configure, and maintain social hierarchies. These hierarchies are established through the labor market, the education system, political institutions, and societal and cultural values. Income, education, occupation, social class, gender, and race/ethnicity are the factors that stratify populations and lead to social hierarchies.

Context, structural mechanisms, and the resultant socioeconomic position of individuals are structural determinants, at the lower left of Figure 4-2, and in effect it is these determinants that are referred to as the social determinants of health inequities. The social determinants of health inequities operate through a set of intermediary determinants of health, shown at the bottom of the figure, to shape health outcomes. Intermediary determinants include material and psychosocial circumstances, behavioral and/or biological factors, and the health system (Solar and Irwin, 2010).

Positioned in the center of the model as an intermediary determinant is the committee’s framework for lifelong learning for health professionals in understanding and addressing the social determinants of health. To the left of the framework is the population/future health workforce, which forms the pipeline for the education and production of future health professionals. Through the transformative learning approach described in the framework, health professionals, students, and trainees learn how to establish equal partnerships with communities, other sectors, and other professions for better understanding of and action on the social determinants of health. They also gain competency in addressing health system complexities within an increasingly global and interconnected world. The result is a workforce that partners to address the social determinants of health for the ultimate goal of an impact on equity in health and well-being.

The measurable output of the framework is a diverse and inclusive workforce that partners with other sectors, community organizations, community members, and other health professions to address and act on the social determinants of health. Monitoring and evaluation of this output would track progress on recruitment and retention of a diverse health professional student body and faculty that also mirrors local populations.

BUILDING THE EVIDENCE BASE

The committee’s data collection and literature review efforts made clear that the impact on health professionals, students, and trainees of transformative learning that addresses the social determinants of health to effect the desired outcomes has not been well studied. And while the committee believes that such research would reveal positive impacts, there remains a relative lack of outcome research that goes beyond learning. Despite this research gap, promising educational practices and experiences reveal that community engagement—pursued in a respectful, informed, and sustainable

manner—is critical to the effective education of health professionals in addressing the social determinants of health (Bainbridge et al., 2014; Feder et al., 2013). However, even lessons learned from educational experiences designed to impact the social determinants of health are not well articulated in the literature, nor are they widely disseminated. As a consequence, there remains a need to identify factors and processes that are common to promising practices and experiences to inform the education of health professionals in understanding and acting on the social determinants of health.

Such analyses would go beyond self-examination to include input from community partners to demonstrate objective and subjective impacts. These efforts would inform best practices for transformative learning. Given the need for evidence that learning in and with communities impacts the social determinants of health, the committee makes the following recommendation for building the evidence base:

Recommendation 4: Governments, health professional and educational associations and organizations, and community organizations should use the committee’s framework and model to guide and support evaluation research aimed at identifying and illustrating effective approaches for learning about the social determinants of health in and with communities while improving health outcomes, thereby building the evidence base.

To demonstrate full and equal partnerships, health professional and educational associations and organizations and community partners should prepare their respective networks to engage with one another in a systematic, comprehensive inquiry aimed at building the evidence base.

The committee also proposes an approach that, if undertaken, could provide strategic direction for efforts to build the evidence base in and with communities (see Box 4-5).

MOVING FORWARD

There are many challenges to educating health professionals to understand and act upon the social determinants of health in and with communities. Designing and instituting robust experiences is time-consuming for faculty and others. The process is labor-intensive and requires a strong commitment from the community, whose trust must be gained over time through demonstration of the value of partnerships. Such partnerships are not stagnant; rather, they must be flexible to evolve as community needs and desires change over time. The need for such flexibility can present difficulties for educators, who are often underresourced. Other challenges stem from learners themselves, who may be resistant to community experi-

ences that shift power from the learner or the provider to the community and its members. Finding faculty who understand and can offer effective learning opportunities that demonstrate how the social determinants of health impact individuals, populations, and communities poses an additional challenge.

Despite these challenges, the potential financial, social, and political returns from such an investment in education are great. The first is improved community relations. At a time of community distrust and turmoil, creating strong partnerships that demonstrate support over time could help ease tensions within communities. Second, community interventions could create pathways for young people from underperforming communities to

enter the health professions and give back to their community as providers and role models for future generations. Third, health care providers and their students and trainees could become more effective clinicians by understanding the entire health system and how external economic, financial, and policy forces can impact the home, family, and community in which a patient resides. Fourth, by exposing learners to other professions and other sectors, working in the community could create a broader understanding of health systems and how interactions among partners are essential for impacting individual and population health outcomes, which in turn generates demonstrable cost savings for payers of health care. Finally, in a time of increasing globalization, migration, and mixing of cultures, building a workforce that can work in and with different communities could increase the effectiveness of early interventions that can improve quality of life while decreasing costs associated with interventions undertaken later on.

Support from multiple stakeholders at all levels will be necessary for these benefits to be realized. Garnering that support will require reaching beyond traditional health professional education pedagogy and silos and engaging new players, such as community health workers and other trusted members of the community, in equal partnership to address community concerns while educating health professionals (Johnson et al., 2012; Torres et al., 2014). Planning will also be necessary to engage nonhealth sectors such as education (e.g., at the primary and secondary levels), labor, housing, transportation, urban planning, community development, and public policy.

Financing has traditionally been an obstacle to offering robust opportunities for any of the components of the framework. Finding the necessary resources needs to start with a strong commitment from organizations and leaders based on the realization that without adequate and sustained funding, efforts toward transformative learning will remain predominantly one-off, ad hoc initiatives by motivated but often overburdened, undersupported individuals. Health professionals are in key positions to impact the social determinants of health if they act in a coordinated manner. A detailed description of the financing of health professional education is beyond this committee’s charge; nonetheless, given the critical role of funding in fulfilling the vision of transformative learning set forth in this report, the committee believes it is important to make a few points on this topic.

First, governments and ministries are in a position to redirect incentives for real and sustained community engagement through funding mechanisms, special tax status, and educational requirements. Some governments, ministries, and foundations are also in a position to direct research support toward efforts to demonstrate the value of partnerships for improving certain indicators of success, such as financial savings and the health and well-being of communities across generations.

Second, anyone with a stake in how health professionals are educated and trained can become an advocate for experiential learning addressing the social determinants of health. As discussed in Chapter 1, many groups have called for action on the social determinants of health. Each such group can exert pressure to update curricula to better reflect the world in which health professionals are expected to work. Health professionals trained to be critical thinkers are better positioned to function effectively in today’s world, in which they increasingly must work with others in and outside of the health system. With specific exposure and training in policy, even students and representatives from small organizations and institutions can play a role in advocating for changes in funding to support education that demonstrates value to communities. This advocacy might involve partnerships between community organizations and universities to establish or improve education pipelines so as to increase the representation of community members in education and the local health workforce.

Finally, to advocate effectively for change, it will be necessary to have population-based data demonstrating the value of investments in the education of health professionals in addressing the social determinants of health in and with communities to all stakeholders in terms of finances, health improvements, and quality of life. Despite even the best evidence, however, resistance to change is likely. Forcing a shift in education through accreditation standards could result in health professional education reflecting more of the framework components. However, to achieve transformative learning based on the framework that can create the envisioned systems thinkers and inspired lifelong learners about the social determinants of health, support for educators will be necessary. The lack of such support could result in lackluster or segmented course offerings related to the social determinants of health and even damage to community relations if learning institutions minimally complied with regulations. In this regard, educational leadership could be held accountable through policy and other reviews conducted by advocates such as students and faculty who understood the need for a new paradigm for learning about and acting on the social determinants of health.

In closing, the committee reiterates that passive learning is not sufficient to fully develop the competencies needed by health professionals to understand and address the social determinants of health. To impact health equity, health professionals need to translate knowledge to action, which requires more than accruing knowledge. Health professionals need to develop appropriate skills and attitudes to be advocates for change. Governments, ministries, communities, foundations, and health professional and educational associations all have a role in how health professionals learn to address the social determinants of health. Using the committee’s framework and associated conceptual model as a guide, these groups can visualize how organizations, educational institutions and associations, and communities

can come together to eliminate health inequities through collective actions. The realization of this vision begins with building a competent health workforce that is appropriately educated and trained to address the social determinants of health.

REFERENCES

AAMC (Association of American Medical Colleges). 2002. The scholarship of community engagement: Using promotion and tenure guidelines to support faculty work in communities. https://depts.washington.edu/ccph/pdf_files/AAMC.pdf (accessed September 22, 2016).

Abdulrahim, S., M. El Shareef, M. Alameddine, R. A. Afifi, and S. Hammad. 2010. The potentials and challenges of an academic-community partnership in a low-trust urban context. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 87(6):1017-1020.

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2014. Evidence-based practice center systematic review protocol: Improving cultural competence to reduce health disparities for priority populations. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/573/1934/cultural-competence-protocol-140709.pdf (accessed September 22, 2016).

Anderson, E. S., R. Smith, and L. N. Thorpe. 2010. Learning from lives together: Medical and social work students’ experiences of learning from people with disabilities in the community. Health & Social Care in the Community 18(3):229-240.

Anderson, L. M., S. C. Scrimshaw, M. T. Fullilove, J. E. Fielding, J. Normand, and the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. 2003. Culturally competent healthcare systems. A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 24(Suppl. 3):68-79.

Art, B., L. De Roo, and J. De Maeseneer. 2007. Towards Unity for Health utilising community-oriented primary care in education and practice. Education for Health (Abingdon, England) 20(2):74.

Bainbridge, L., S. Grossman, S. Dharamsi, J. Porter, and V. Wood. 2014. Engagement studios: Students and communities working to address the determinants of health. Education for Health (Abingdon, England) 27(1):78-82.

Barman, A., R. Jaafar, and N. M. Ismail. 2006. Problem-based learning as perceived by dental students in Universiti Sains Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences 13(1):63-67.

Berk, R. A. 2009. Using the 360 degrees multisource feedback model to evaluate teaching and professionalism. Medical Teacher 31(12):1073-1080.

Bhatia, R., L. Farhang, J. Heller, M. Lee, M. Orenstein, M. Richardson, and A. Wernham. 2014. Minimum elements and practice standards for health impact assessment, version 3, September. Oakland, CA: HIA Practice Standards Working Group.

Blumenthal, D. S. 2011. Is community-based participatory research possible? American Journal of Preventive Medicine 40(3):386-389.

Brauer, D. G., and K. J. Ferguson. 2015. The integrated curriculum in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 96. Medical Teacher 37(4):312-322.

Bringle, R. G., J. A. Hatcher, S. Jones, and W. M. Plater. 2006. Sustaining civic engagement: Faculty development, roles, and rewards. Metropolitan Universities 17(1):62-74.

Buckner, A. V., Y. D. Ndjakani, B. Banks, and D. S. Blumenthal. 2010. Using service-learning to teach community health: The Morehouse School of Medicine community health course. Academic Medicine 85(10):1645-1651.

Burnett, S. M., M. K. Mbonye, S. Naikoba, S. Zawedde-Muyanja, S. N. Kinoti, A. Ronald, T. Rubashembusya, K. S. Willis, R. Colebunders, Y. C. Manabe, and M. R. Weaver. 2015. Effect of educational outreach timing and duration on facility performance for infectious disease care in Uganda: A trial with pre-post and cluster randomized controlled components. PLoS ONE 10(9):e0136966.

BUSM (Boston University School of Medicine). 2015. Minority Faculty Leadership & Career Development Program. http://www.bumc.bu.edu/facdev-medicine/facdevprograms/minority-faculty-leadership-career-development-program (accessed September 22, 2016).

Butts, G. C., Y. Hurd, A. G. S. Palermo, D. Delbrune, S. Saran, C. Zony, and T. A. Krulwich. 2012. Role of institutional climate in fostering diversity in biomedical research workforce: A case study. The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, New York 79(4):498-511.

Caldron, P. H., A. Impens, M. Pavlova, and W. Groot. 2015. A systematic review of social, economic and diplomatic aspects of short-term medical missions. BMC Health Services Research 15:380.

Calleson, D. C., S. D. Seifer, and C. Maurana. 2002. Forces affecting community involvement of AHCS: Perspectives of institutional and faculty leaders. Academic Medicine 77(1):72-81.

Cambridge University Press. 2016. Organization. http://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/organization (accessed May 31, 2016).

Campbell, C., K. Scott, M. Nhamo, C. Nyamukapa, C. Madanhire, M. Skovdal, L. Sherr, and S. Gregson. 2013a. Social capital and HIV competent communities: The role of community groups in managing HIV/AIDS in rural Zimbabwe. AIDS Care 25(Suppl. 1):S114-S122.

Campbell, C., M. Nhamo, K. Scott, C. Madanhire, C. Nyamukapa, M. Skovdal, and S. Gregson. 2013b. The role of community conversations in facilitating local HIV competence: Case study from rural Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health 13:354.

Carman, A. L. 2015. Collective impact through public health and academic partnerships: A Kentucky public health accreditation readiness example. Frontiers in Public Health 3:44.

Cashman, S., J. Hale, L. Candib, T. A. Nimiroski, and D. Brookings. 2004. Applying service-learning through a community-academic partnership: Depression screening at a federally funded community health center. Education for Health (Abingdon, England) 17(3):313-322.

Cené, C. W., M. E. Peek, E. Jacobs, and C. R. Horowitz. 2010. Community-based teaching about health disparities: Combining education, scholarship, and community service. Journal of General Internal Medicine 25 (Suppl 2.):S130-S135.

Chou, C. L., K. Hirschmann, A. H. Fortin VII, and P. R. Lichstein. 2014. The impact of a faculty learning community on professional and personal development: The facilitator training program of the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare. Academic Medicine 89(7):1051-1056.

Christopher, S., V. Watts, A. K. H. G. McCormick, and S. Young. 2008. Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. American Journal of Public Health 98(8):1398-1406.

Collins, J., and J. Koplan. 2009. Health impact assessment: A step toward health in all policies. Journal of the American Medical Association 302(3):315-317.

Cónsul-Giribet, M., and J. L. Medina-Moya. 2014. Strengths and weaknesses of problem based learning from the professional perspective of registered nurses. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem 22(5):724-730.

Council of the European Union. 2002. Council resolution of 27 June 2002 on lifelong learning. Official Journal of the European Communities C163/1-C163/3.

Curtis, E., E. Wikaire, K. Stokes, and P. Reid. 2012. Addressing indigenous health workforce inequities: A literature review exploring “best” practice for recruitment into tertiary health programmes. International Journal for Equity in Health 11:13.

Daley, S., D. L. Wingard, and V. Reznik. 2006. Improving the retention of underrepresented minority faculty in academic medicine. Journal of the National Medical Association 98(9):1435-1440.

Dapremont, J. A. 2012. A review of minority recruitment and retention models implemented in undergraduate nursing programs. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 3(2):112-119.

DiGirolamo, A., A. C. Geller, S. A. Tendulkar, P. Patil, and K. Hacker. 2012. Community-based participatory research skills and training needs in a sample of academic researchers from a clinical and translational science center in the northeast. Clinical and Translational Science 5(3):301-305.

Dillenbourg, P. 1999. What do you mean by collaborative learning? In Collaborative-learning: Cognitive and computational approaches, edited by P. Dillenbourg. Oxford, UK: Elsevier. Pp. 1-19.

Donnon, T., A. Al Ansari, S. Al Alawi, and C. Violato. 2014. The reliability, validity, and feasibility of multisource feedback physician assessment: A systematic review. Academic Medicine 89(3):511-516.

Dooly, M. 2008. Constructing knowledge together. In Telecollaborative language learning: A guidebook to moderating intercultural collaboration online, edited by M. Dooly. Bern, NY: Peter Lang. Pp. 21-45.

Doran, K. M., K. Kirley, A. R. Barnosky, J. C. Williams, and J. E. Cheng. 2008. Developing a novel poverty in healthcare curriculum for medical students at the University of Michigan Medical School. Academic Medicine 83(1):5-13.

Economos, C. D., and S. Irish-Hauser. 2007. Community interventions: A brief overview and their application to the obesity epidemic. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 35(1):131-137.

Edutopia. 2016. Project-based learning. http://www.edutopia.org/project-based-learning (accessed January 11, 2016).

El-Sayed, M., and J. El-Sayed. 2014. Achieving lifelong learning outcomes in professional degree programs. International Journal of Process Education 6(1):37-42.

Feder, E., C. Moran, A. Gargano Ahmed, S. Lessem, and R. Steidl. 2013. Limiting retail alcohol outlets in the Greenbush-Vilas neighborhood, Madison, Wisconsin: A health impact assessment. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute.

FIP (International Pharmaceutical Federation). 2014. Continuing professional development/continuing education in pharmacy: Global report. The Hague, The Netherlands: FIP.

Franz, N. K. 2002. Transformative learning in extension staff partnerships: Facilitating personal, joint, and organizational change. Paper presented at Annual Meeting of the Association for Leadership Education, Lexington, KY, July 11-13.

Freeman, R. B., and W. Huang. 2014. Collaboration: Strength in diversity. Nature 513(7518):305.

Frenk, J., L. Chen, Z. A. Bhutta, J. Cohen, N. Crisp, T. Evans, H. Fineberg, P. Garcia, Y. Ke, P. Kelley, B. Kistnasamy, A. Meleis, D. Naylor, A. Pablos-Mendez, S. Reddy, S. Scrimshaw, J. Sepulveda, D. Serwadda, and H. Zurayk. 2010. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 376(9756):1923-1958.

Frenk, J., D. J. Hunter, and I. Lapp. 2015. A renewed vision for higher education in public health. American Journal of Public Health 105(Suppl. 1):S109-S113.

Furco, A. 1996. Service-learning: A balanced approach to experiential education. In Expanding boundaries: Serving and learning, edited by B. Taylor and Corporation for National Service. Washington, DC: Corporation for National Service. Pp. 2-6.

Gelmon, S., K. Ryan, L. Blanchard, and S. D. Seifer. 2012. Building capacity for community-engaged scholarship: Evaluation of the faculty development component of the faculty for the engaged campus initiative. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 16(1):21-45.

Goldberg-Freeman, C., N. E. Kass, P. Tracey, G. Ross, B. Bates-Hopkins, L. Purnell, B. Canniffe, and M. Farfel. 2007. “You’ve got to understand community”: Community perceptions on “breaking the disconnect” between researchers and communities. Progress in Community Health Partnerships 1(3):231-240.

Heller, J., M. L. Givens, T. K. Yuen, S. Gould, M. B. Jandu, E. Bourcier, and T. Choi. 2014. Advancing efforts to achieve health equity: Equity metrics for health impact assessment practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11(11):11054-11064.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2010. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: HHS. http://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/HP2020_brochure_with_LHI_508_FNL.pdf (accessed January 11, 2016).

Hoever, I. J., D. van Knippenberg, W. P. van Ginkel, and H. G. Barkema. 2012. Fostering team creativity: Perspective taking as key to unlocking diversity’s potential. Journal of Applied Physiology 97(5):982-996.

Holland, B., and J. A. Ramaley. 2008. Creating a supportive environment for community-university engagement: Conceptual frameworks. Sydney, New South Wales: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia, Inc. (HERDSA).

Howard, K. M., T. Stewart, W. Woodall, K. Kingsley, and M. Ditmyer. 2009. An integrated curriculum: Evolution, evaluation, and future direction. Journal of Dental Education 73(8):962-971.

Hunt, J. B., C. Bonham, and L. Jones. 2011. Understanding the goals of service learning and community-based medical education: A systematic review. Academic Medicine 86(2):246-251.

Ivicek, K., A. B. de Castro, M. K. Salazar, H. H. Murphy, and M. Keifer. 2011. Using problem-based learning for occupational and environmental health nursing education: Pesticide exposures among migrant agricultural workers. Journal of the American Association of Occupational Health Nurses 59(3):127-133.

Jagosh, J., P. Bush, J. Salsberg, A. Macaulay, T. Greenhalgh, G. Wong, M. Cargo, L. Green, C. Herbert, and P. Pluye. 2015. A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: Partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health 15(1):725.

Johnson, D., P. Saavedra, E. Sun, A. Stageman, D. Grovet, C. Alfero, C. Maynes, B. Skipper, W. Powell, and A. Kaufman. 2012. Community health workers and Medicaid managed care in New Mexico. Journal of Community Health 37(3):563-571.

Jordan, C., W. J. Doherty, R. Jones-Webb, N. Cook, G. Dubrow, and T. J. Mendenhall. 2012. Competency-based faculty development in community-engaged scholarship: A diffusion of innovation approach. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 16(1):65-96.

Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation. 2010. Lifelong learning in medicine and nursing: Final conference report. New York: Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation. http://www.aacn.nche.edu/educationresources/MacyReport.pdf (accessed September 22, 2016).

Kelley, M. A., W. Baldyga, F. Barajas, and M. Rodriguez-Sanchez. 2005. Capturing change in a community-university partnership: The ¡sí se puede! Project. Preventing Chronic Disease 2(2):A22.

Khoiriyah, U., C. Roberts, C. Jorm, and C. P. M. Van der Vleuten. 2015. Enhancing students’ learning in problem based learning: Validation of a self-assessment scale for active learning and critical thinking. BMC Medical Education 15:140.

Kickbusch, I. 2013. A game change in global health: The best is yet to come. Public Health Reviews 35(1).

Kitto, S., J. Goldman, M. H. Schmitt, and C. A. Olson. 2014. Examining the intersections between continuing education, interprofessional education and workplace learning. Journal of Interprofessional Care 28(3):183-185.

Kolb, D. A. 1984. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kreiner, M. 2009. Delivering diversity: Newly regulated midwifery returns to Manitoba, Canada, one community at a time. The Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health 54(1):e1-e10.

Kretzmann, J. P., J. L. McKnight, S. Dobrowolski, D. Puntenney. 2005. Discovering community power: A guide to mobilizing local assets and your organization’s capacity. Evanston, IL: Asset Based Community Development Institute, Northwestern University. http://www.abcdinstitute.org/docs/kelloggabcd.pdf (accessed September 22, 2016).

Ladhani, Z., F. J. Stevens, and A. J. Scherpbier. 2013. Competence, commitment and opportunity: An exploration of faculty views and perceptions on community-based education. BMC Medical Education 13(1):167.

Lane, E. A. 2008. Problem-based learning in veterinary education. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education 35(4):631-636.

Langlois, J. P., and S. B. Thach. 2003. Bringing faculty development to community-based preceptors. Academic Medicine 78(2):150-155.

LaVeist, T. A., and G. Pierre. 2014. Integrating the 3Ds-social determinants, health disparities, and health-care workforce diversity. Public Health Reports-US 129(Suppl. 2):9-14.