Appendix A

Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants of Health

Sara Willems, Ph.D., M.Sc.

Kaatje Van Roy, Ph.D., M.D., M.Sc.

Jan De Maeseneer, Ph.D., M.D.

INTRODUCTION

In 2015, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) convened a committee on educating health professionals to address the social determinants of health. A thorough search of the literature was needed in order for the committee to respond to its statement of task. This paper provides a review of the literature that describes the current practice of educating health professionals to address the social determinants of health in and with communities. Based on these findings, we formulate recommendations on how to strengthen health professional education by addressing the social determinants of health.

METHODS

Data Search

For this study, the Research Library of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine conducted a literature search using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Embase, Proquest, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search terms were developed by IOM staff and study consultants. These search terms can be grouped into three categories: terms related to primary social determinants, to health professions, and to education/learning (see Box A-1).

The date range for the literature search was from 2000 to the present. Both U.S. and international materials were examined. Classroom and

technology education were excluded from the search. The search was conducted between July 9 and July 14, 2015. This initial database search resulted in 297 papers. A team at the Department of Family Medicine and Primary Health Care of Ghent University then conducted an analysis of the identified papers. The team consisted of Sara Willems, master in health promotion and professor in health equity; Kaatje Van Roy, medical doctor, psychologist, and senior researcher; and Jan De Maeseneer, medical doctor, full professor in family medicine, and head of the department.

The team added four papers to the literature review, based on recommendations of consulted experts. Next, all papers were screened using the following inclusion criteria:

- The paper describes a training program for health care students or professionals.

- The described training program includes some form of experiential learning outside the classroom.

- The description of the learning aims, content, or outcome of the program refers to social determinants of health.

The screening was done independently by two researchers and in case of a different score, the paper was discussed until consensus was reached.

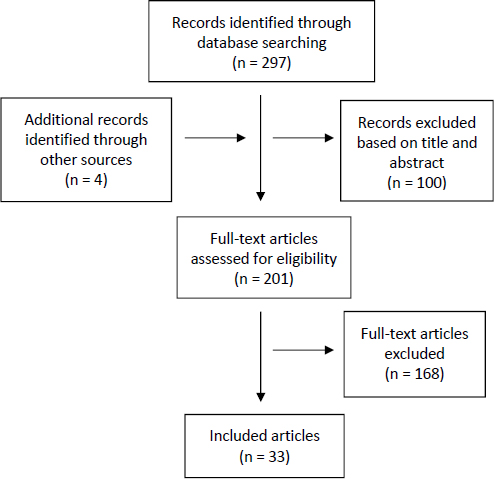

A first screening, based on titles and abstracts, resulted in the exclusion of 100 papers. During a second screening phase based on the full text of the remaining papers, another 168 papers were excluded. This two-phase screening process finally resulted in 33 papers being included in this review (see Figure A-1).

Data Analysis

In line with the research questions of the present study, we designed an analytic instrument that allowed us to extract relevant information from each of the papers in a systematic way. This screening instrument allowed us to categorize the papers in terms of type of paper (e.g., research paper versus descriptive paper) and to extract details about the training program (e.g., duration of the training, the type of community that was involved in the program, information about the participants, the goal and the content of the program, the theoretical framework and pedagogical approach that were used). For the research papers, we also extracted information on the research aim, the method that was used, the number of participants, relevant findings for the present study, etc. The screening tool can be found in Annex A-1 at the end of this appendix.

RESULTS

Global Descriptions of the Programs

Location of the Schools Where the Programs Run

As noted, 33 papers describing training programs for health professional students addressing the social determinants of health in/with the community were found. Two papers reported on programs of the same school. The vast majority of the programs are from the United States (n = 24). The other schools are located in Canada (n = 6), Australia (n = 1), Belgium (n = 1), and Serbia (n = 1).

Type of Students for Which the Program Was Designed

Type of health profession Most programs are designed for medical (n = 10) and nursing (n = 8) students. Other included programs address pharmacy (n = 2), nurse practitioner (n = 1), physician assistant (n = 1), dentistry (n = 1), and art therapy students (n = 1). A considerable number of programs simultaneously involve students from different disciplines, including, for instance, medical, nursing, social work, and/or law students (n = 7). In these mixed groups, interprofessional learning often is an explicit learning objective.

Level Programs aim at students of different levels of training, including undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral. One program provides training to a mix of student levels; the service-learning program at the University of Arizona requires master’s students to complete one course among five,

whereas Ph.D. students are required to complete two of the five (optionally one in co-teaching) (Sabo et al., 2015). Although none of the included programs was designed for health professionals, some programs were designed for students who already had some professional experience, such as registered nurse (R.N.)/bachelor of science in nursing (B.S.N.) students (Ezeonwu et al., 2014). Because of differences in terminology used (e.g., “undergraduate,” “postbaccalaureate,” “senior-level traditional students”), it sometimes proved difficult to evaluate the students’ level.

Place of the Program in the Curriculum

While some programs are an obligatory component of the curriculum, others are elective or even extracurricular. In a limited number of cases, only selected students can attend the program. The selection procedure often comprises a written application exploring students’ interests, previous experiences, and professional goals, sometimes combined with an interview (e.g., Bakshi et al., 2015; Kassam et al., 2013; Meili et al., 2011).

Length and Intensity of the Training

Programs largely vary with regard to their length and intensity. Program lengths range from approximately 1 week (e.g., Art et al., 2008), to over one semester (e.g., Bell and Buelow, 2014) to several years (e.g., Meurer et al., 2011). Furthermore, some of the programs are very intense (e.g., full-time presence in a community during an immersion experience abroad [Kassam et al., 2013; Meili et al., 2011]), while some are much less so (e.g., 1 hour per week [Kelly, 2013]). However, because of a lack of information, it is often difficult to get an encompassing idea of a program’s extent. Moreover, programs vary in the amount of time dedicated to experiential learning versus time that is preserved for nonexperiential learning (more information on course content is provided below).

Communities Involved in the Training

Local communities In most programs, students have learning experiences in local communities. Community agencies and care providers that are involved in the programs comprise homeless shelters, domestic violence shelters, community health centers, schools, AIDS support organizations, substance abuse recovery centers, elderly homes, humanitarian organizations, free clinics, and others. Correspondingly, students work with a large variety of populations, such as low-income populations, homeless people, native populations, migrant populations, and ethnic minority groups.

Communities abroad Some of the included programs provide international experiences to students. These include, for instance, a 6-week immersion in an AIDS support organization in Uganda (Kassam et al., 2013) and a 2-week stay at an indigenous Mayan community in Guatemala (Larson et al., 2010). One of the programs offers highly comprehensive training, including a 6-week stay in an Aboriginal community, a long-term engagement at an urban student-run clinic, and a 6-week stay at a rural hospital in Mozambique (Meili et al., 2011).

Theoretical Framework and Program Goals

Theoretical Framework

Programs are rooted within theoretical frameworks to various extents. Examples of such frameworks include cultural competence, social justice, social responsibility, social accountability, human rights, patient-centered care, and advocacy for patient health.

Program Goals

In many of the included papers, the program goals are more or less clearly stated. However, the extent to which these goals include learning about social determinants of health in an explicit way varies among the papers. Four types of goals were identified:

- The goals explicitly mention the social determinants of health (n = 9) (e.g., “to foster a better understanding of social determinants of health and ways of addressing health disparities” [Dharamsi et al., 2010a]).

- The goals mention health inequity or health disparities (n = 11) (e.g., “to provide the students the skills to plan, implement and evaluate a health disparity project” [Parks et al., 2015]).

- The goals implicitly refer to the social determinants of health (n = 12) (e.g., “to enhance students’ knowledge and understanding of health issues and healthcare practice in rural and underserved communities” [Clithero et al., 2013]).

- Learning about the social determinants of health is not mentioned in the program goals, but appears to be an effect of the program (n = 1) (e.g., “It is evident that the nursing student learned about the influence of poverty on the health of children” [Ogenchuk et al., 2014]).

Some programs do not only define general learning goals but also require the students to outline some individual learning objectives (e.g., Brown et al., 2007; Meurer et al., 2011).

Pedagogical/Educational Approaches

Given the specific inclusion criteria that were used, learning approaches that do not include an experiential component in or with a community were excluded. “Service learning” appeared to be the most commonly used term in the included papers (at times combined with qualifier, as in “community service learning” or “international service learning”). In some papers, the authors provide background information about the way “service learning” is understood. The most commonly encountered understanding of service learning is presented in Box A-2. Another closely related term is “community-based learning.” Other programs (additionally) focus on “interprofessional learning” or “interdisciplinary learning,” in which different types of health students must work together. Less frequently encountered approaches include “community-oriented primary care” (e.g., Art et al., 2008) and “community-based participatory research” (e.g., Parks et al., 2015). Finally, there are some differences with regard to the setting in which learning takes place. Most often, the students spend time working in and with communities. A different approach is student-run clinics that provide health services to underserved neighborhoods or communities (Meili et al., 2011; Sheu et al., 2012).

Program Components

The actual learning experience in the community can take various forms. Often-encountered components include conducting community (health) needs assessment, developing and implementing a project or intervention, organizing educational sessions for community members, and caring for individual patients.

Community needs assessment can be conducted through observation, windshield surveys, a review of demographic and health statistics, interviews with key informants, or focus groups with community members (e.g., Art et al., 2008; Dharamsi et al., 2010a; Ezeonwu et al., 2014; Kruger et al., 2010). Such needs assessment often serves as a first step in a community service learning project. After identifying the community needs, students gather further information and develop—in close collaboration with local community workers—a project that could counter one of these needs (e.g., Dharamsi et al., 2010a; Ezeonwu et al., 2014).

Teaching and interaction with community members are also often part of the program. In some programs, students organize health education sessions for the community members addressing different health-related topics (e.g., Bell and Buelow, 2014; Jarrell et al., 2014; Stanley, 2013; Ward et al., 2007). Getting to know community members and their living conditions includes, for instance, home visits (Art et al., 2008; De Los Santos et al., 2014), reading with children (Kelly, 2013), or art therapy students visiting a shelter for homeless persons and finding out what can be done with the children (Feen-Calligan, 2008). In an international learning experience with indigenous Mayan communities (Larson et al., 2010), students are lodged with families, often confronting daily life issues. One of the programs includes a component called “My Patient,” in which the student follows a patient through his or her contacts with health care services and other health institutions and family settings. After each such visit, the student interviews the patient for at least 45 minutes (Matejic et al., 2012).

Taking care of individual community members is another component of some programs. Care for individual community members includes, for instance, home visits that focus on health education, arrangement of referrals, evaluation and improvement of health literacy, and development of an interprofessional care plan (De Los Santos et al., 2014). In some programs, a specific household or family is followed up by a student or an interprofessional group of students (e.g., De Los Santos et al., 2014; Ward et al., 2007). The Interprofessional Patient Advocacy course (Bell and Buelow, 2014) includes patient advocacy work ranging from helping patients complete applications or recertifications for Medicaid, housing, food stamps, or child care benefits; to providing support to patients with chronic conditions; to assisting in setting up health programs. Another way

students carry out their health advocacy role is, for instance, writing a letter to the editor (Dharamsi et al., 2010a) or presenting survey findings to local key decision makers (Clithero et al., 2013). Profession-related care can also be part of the program. Examples include taking health histories, assisting local physicians with health assessments (Larson et al., 2010), providing foot care to persons in a homeless shelter (Schoon et al., 2012), and filling prescriptions or counseling patients (Brown et al., 2007). Learning to take care of patients and the community can also consist of shadowing a local community physician (Clithero et al., 2013; Kassam et al., 2013).

Sometimes, the experience is integrated into an already existing part of the curriculum. Sharma (2014), for example, describes a program that is integrated into medical residency training. Basically, the program incorporates reflection on the social determinants of health in the residents’ daily work. For instance, the morning briefing is seen as a daily opportunity for discussion of root causes of ill health and is followed by an online blog. Moreover, during daily noon presentations, three additional questions are introduced systematically: (1) How do the social determinants of health pertain to your topic?, (2) How are certain groups at increased risk?, and (3) What are advocacy opportunities for physicians at the clinical or policy level?

In several programs, the experiential learning component is embedded in a broad approach that encompasses lectures, group discussions, workshops to build capacities (Dharamsi et al., 2010a), simulation experiences,1 reading assignments,2 online activities, including discussion fora with peers (e.g., Ezeonwu et al., 2014), presentations (e.g., Bell and Buelow, 2014; Ezeonwu et al., 2014), networking with alumni to promote project and career development (Williams et al., 2012), and research projects (e.g., Bakshi et al., 2015; Mudarikwa et al., 2010; Parks et al., 2015).

Reflective Learning

Personal reflection activities appear to be part of several programs. Several authors emphasize reflection as an indispensable component of true learning (e.g., Brown et al., 2007). According to Kelly (2013, p. 33), “the reflection piece truly separates service learning from volunteerism.” Other authors draw attention to the fact that exposure alone does not guarantee better understanding and may even reinforce prejudice and stereotypes. Ezeonwu and colleagues (2014, p. 278) state that “it is the quality of reflection—thinking about the complex health care issues and using real life experiences to suggest questions for further exploration that transforms service into service

___________________

1 Examples include an online poverty simulation (Bell and Buelow, 2014) and assessing barriers by stepping into the patient’s role (Bussey-Jones et al., 2014).

2 Actual examples of reading assignment texts are provided in Clithero et al. (2013).

learning.” This is also confirmed by students stating that “the process of critical reflection is key to learning” (Dharamsi et al., 2010b). And by analyzing students’ clinical journals, Bell and Buelow (2014) found that patient interactions often were only the start of learning, and that later self-reflection produced a more compelling understanding of the impact of poverty.

Reflection can be achieved in different ways. The range of reflective exercises includes

- keeping a daily reflective journal during the service experience;

- writing a report at the end of the experience;

- preparing a presentation for the trainers, community partners, and/or fellow students;

- discussing with peers face-to-face or on an online forum; and

- photo-journaling.

In some cases, reflection is facilitated by the use of guiding questions (Ogenchuk et al., 2014), instruction to write on structured topics (see Box A-3), or use of the “critical incident technique” (Dharamsi et al., 2010a). Of interest, Kelly (2013, p. 33) notes that for true service learning, (medical) students need to be placed in an experience that is not part of their discipline, “as it allows students to set aside their medical skill sets and knowledge and genuinely focus on the community and the community issues.”

Evaluation and Outcomes of the Programs

Many papers include some sort of evaluation of the program they describe. Such evaluation is obtained by means of quantitative data (n = 4), qualitative data (n = 7), a mix of qualitative and quantitative data (n = 9), or a rather informal and nonsystematic process (n = 8). Quantitative data basically rely on surveys measuring students’ evaluation of and satisfaction with different aspects of the training, their career choices or readiness for interprofessional learning, and their attitudes toward the specific population with which they worked.3 Qualitative data comprise mainly information obtained from students’ reflective journals, focus groups, and interviews (most often with students, sometimes with trainers or community members). The impact of the program on students’ identity, attitudes, cultural competence, etc., is the most prevalent type of qualitative data. Informal and nonsystematic evaluations stem principally from students’ reflective journals and debriefing sessions. Generally, most such data are self-reported (students being asked about their own changes in attitudes or perceptions).

Students’ Attitudes, Awareness, Understanding, and Skills

Frequently, students’ awareness and understanding of the social determinants of health had deepened after the learning experience (e.g., Brown et al., 2007; Loewenson and Hunt, 2011; Schoon et al., 2012). They were able to see the bigger picture (Kruger et al., 2010), became aware of the impact of a lack of resources (Jarrell et al., 2014), and gained more insight into the complexity of the daily reality of community members (e.g., Meili et al., 2011).4 Others bore witness to the fact that abstract concepts had turned into real experiences (Dharamsi et al., 2010b; Meili et al., 2011), as illustrated by this quote from one student: “Had you asked me before this experience what community health is I would have given you a definition. If you ask me now, I’ll give you names, stories, laughs, somberness and actions” (Meili et al., 2011, p. 4). Students also acquired a better apperception of their future role as a health professional (Kruger et al., 2010).

Along with increased awareness and understanding, the learning experience affected students’ attitudes at times. For instance, students showed more positive and nonstigmatizing attitudes toward homeless individuals after participating in structured clinical service-learning rotations with

___________________

3 For example, Medical Student Attitudes Toward the Underserved (MSATU) (Bussey-Jones et al., 2014), Attitudes Toward Homelessness Inventory (ATHI) (Loewenson and Hunt, 2011), Belief in a Just World Scale (JWS), and Attitudes about Poverty and Poor People Scale (APPPS) (Jarrell et al., 2014).

4 For example, by observing the distances the community members need to travel for appropriate health care (Meili et al., 2011).

homeless persons, and reported stronger beliefs, in the potential for viable programs or solutions to address homelessness (Loewenson and Hunt, 2011). Students also challenged their own stereotypes (Dharamsi et al., 2010b), beliefs, and attitudes with regard to the vulnerable populations with which they worked and discovered how much these people “were just like them” (Rasmor et al., 2014; Stanley, 2013). This was in contrast with the findings of another study that service learning can increase students’ empathy toward those who live in poverty while at the same time solidifying perceptions that the poor are different from other members of society (Jarrell et al., 2014). Moreover, changes reported in the papers using quantitative analysis often are not statistically significant (e.g., Clithero et al., 2013; Jarrell et al., 2014; Rasmor et al., 2014; Sheu et al., 2012), so that solid conclusions on the actual effect of the training are difficult to draw.

After the learning experience, students often felt increased comfort in working with specific communities (Brown et al., 2007; Dharamsi et al., 2010a; Ierardi and Goldberg, 2014; Loewenson and Hunt, 2011). Gaining an understanding of the social determinants of health also helped the participants advocate for patients from vulnerable populations (Bakshi et al., 2015).

Interprofessionalism

The training programs that focused on interprofessionalism or interdisciplinarity often achieved their goals: students valued the interdisciplinary work (Art et al., 2008; Ierardi and Goldberg, 2014) and felt more ready for interprofessional learning (Sheu et al., 2012). Moreover, students learned that interdisciplinarity is important in a context of constrained resources (i.e., collaboration is all the more important when the number of professionals is limited) (Meili et al., 2011). Furthermore, O’Brien and colleagues (2014) note that the diversity of students provided a rich experiential base that contributed to monthly reflection sessions.

Long-Term Effects

In several cases, the training had an actual impact on students’ career choices. Programs sometimes appeared to shape the students’ desire to work with underserved populations (Dharamsi et al., 2010a; Meili et al., 2011; O’Brien et al., 2014), although students’ preparedness to contribute to community-based volunteer activities in the future did not always change (Rasmor et al., 2014). Dharamsi and colleagues (2010a) also mention student-reported barriers, such as time limitations and financial obligations. Apart from one study in which students were interviewed 3 or 4 years after the learning experience (Ierardi and Goldberg, 2014), actual long-term

effects could not be assessed, as data were most often gathered immediately after the training.

Most Valued Components

Some papers describe the components students valued most. Students often expressed their preference for interactive, community-based sessions over classroom didactics (Clithero et al., 2013; Meurer et al., 2011), claiming that they were learning more through the former (O’Brien et al., 2014). Students stressed the importance of witnessing and confrontations (Dharamsi et al., 2010a). Among the highest-rated course components for helping to understand their future role as a physician were those involving a physician shadowing experience (Clithero et al., 2013).

Some authors stress the importance of including a variety of training components. Bell and Buelow (2014) state that in their program, “the various experiences were all necessary to ensure achievement of student learning outcomes.” (This program comprises an online poverty simulation, reflection and discussion, several online and in-class lessons with corresponding quizzes, interprofessional team assignments, a home visit, weekly clinical work with reflective journals, and a final team presentation.) Others presume that the reading assignments in their program may explain why even those students who had volunteered in shelters previously experienced growth during the training (Feen-Calligan, 2008).

Need for Guidance

Students need a certain level of guidance with regard to their experiential learning. In one of the programs, students suggested the need to provide more hands-on guidance in planning and implementing the community-based projects (O’Brien et al., 2014). Some papers mention the students’ initial discomfort with having no predetermined protocols (Feen-Calligan, 2008) or their wish for more structure or a guidebook (Dharamsi et al., 2010a). Nonetheless, some students reported that the lack of predetermined protocols helped them really listen to the children with whom they were working (Feen-Calligan, 2008). Other authors even warn that caution is necessary with respect to the information that is provided about the issues a community faces, as this can sometimes lead to forming biases and stereotyping (Kelly, 2013).

Care for the Students

Some of the papers note explicit attention to the students’ well-being. Consideration of students’ well-being is evoked by Kelly (2013, p. 35), who

mentions that “students are generally more comfortable working in pairs, and pairing students together fosters teamwork, confidence, and safety at service-learning sites.” Other authors focus on the fact that the training helped the students protect and foster their idealism (Bakshi et al., 2015) and kept them from becoming cynical (Bakshi et al., 2015; Meili et al., 2011). This was especially the case in elective programs in which the most motivated students were selected to participate.

Nonstudent Evaluations

Almost all papers address the students’ point of view, whereas the point of view of trainers or community members is rarely considered. However, Matejic and colleagues (2012) conducted a quantitative evaluation study involving 1,188 students, 630 patients, and 78 physicians. Remarkably, in this study, patients appeared to be more satisfied with the program than were the students and physicians. Mudarikwa and colleagues (2010) also included the perspective of community educators, who valued the students’ presence and reported some difficulties related to the project. Also of note is that none of the included studies examined the effect of the program on the community’s health.

Cost of the Programs

Most papers include no information on the costs of the program. Occasionally, some information is provided about the size of the workforce required for a program (e.g., Art et al., 2008). O’Brien and colleagues (2014) report that funding constraints limited the number of students that could participate. Some papers mention grants that were available for participating students, mostly to take part in international programs (e.g., Larson et al., 2010; Meili et al., 2011), and occasionally to attend external advocacy skill-building workshops and seminars (Bakshi et al., 2015). In some other cases, program funding was obtained (e.g., Meurer et al., 2011; Sabo et al., 2015).

Difficulties and Bottlenecks

Despite principally positive evaluations, some papers give voice to critical views and describe the difficulties encountered during the program rollout.

Programs often require an enormous amount of time and energy from both the university and the community (Art et al., 2008; Ezeonwu et al., 2014; Kelly, 2013; Sabo et al., 2015). O’Brien and colleagues (2014) state that there is a need to provide salary support to allow faculty and commu-

nity leaders the time for student guidance. Another program (Sabo et al., 2015) engaged doctoral students as co-instructors with the aim of bringing new energy, directions, and partnerships to the course and helping to alleviate potential burnout among faculty and partners. Other logistic difficulties concern, for instance, placement logistics and contextualization of didactic material at community sites (Mudarikwa et al., 2010). Moreover, students working in the community the same day every week was not considered the ideal way to give them insight into day-to-day life in the community (Mudarikwa et al., 2010). Loss of information and continuity as successive student cohorts transitioned in and out of longitudinal projects was also reported (Bakshi et al., 2015).

Some of the papers mention concerns about students’ safety. This was the case, for example, in a program in which students made home visits (Bell and Buelow, 2014). Being accompanied by another student, providing the address and vehicle information to the course faculty, and calling when the visit ended were some of the measures taken to guarantee their safety.

Some authors encountered difficulty in convincing students to participate in the program (Dharamsi et al., 2010b) or to having them keep a reflective journal, although they gradually came to appreciate the latter (Dharamsi et al., 2010b).

CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to obtain an overview of education programs addressing the social determinants of health in and with communities by searching the literature published on this topic. After strict inclusion criteria were applied to the papers in the original database, 33 papers were selected for this review. As mentioned earlier, we found that fewer papers mentioned “social determinants of health” as a goal (n = 9) than mentioned “health inequity” or “health disparity” (n = 11). Unfortunately, “health inequity” and “health disparity” were not included in the search terms. Thus, relevant papers may have been missed. Moreover, time constraints did not allow us to complete this database with screenings of reference lists or with searches for additional information on the Internet (gray literature and possibly relevant websites5). A systematic screening of relevant conference abstract books also was not possible.

The large majority of the programs reviewed (n = 24) are based in the

___________________

5 For example, the websites of Community-Campus Partnerships for Health, https://ccph.memberclicks.net/service-learning (accessed January 15, 2016); Training for Health Equity Network, http://thenetcommunity.org (accessed January 15, 2016); or The Network: Towards Unity for Health, http://www.the-networktufh.org (accessed January 28, 2016).

United States and are focused on medicine (n = 10) and/or nursing students (n = 8). Some programs are obligatory for all students, while others are elective or extracurricular, sometimes available only to selected students. The reasons for allowing only selected students are often not mentioned. Logistic and financial reasons may play a role (Kassam et al., 2013; Meili et al., 2011), as well as ethical reasons (e.g., excluding faculty and students who would participate for personal reasons, thereby harming the community) (Dharamsi et al., 2010b). The particular selection criteria often concern previous experiences, motivations, professional goals, language skills, and quality of reflection and writing (Bakshi et al., 2015; Dharamsi et al., 2010b; Meili et al., 2011), which means that students who are sensitive to the broader social picture often are selected for the programs. The information obtained from the included papers does not allow us to make statements about the impact of a program’s being mandatory or not.

The programs reviewed varied greatly in the length and intensity of the training. Nevertheless, a lack of information often prevented us from getting a clear idea of the amount of time the students spent on each of the program components. Moreover, it was often difficult to conclude whether the programs were integrated in a set of study modules or isolated. Moreover, based on the available information, it was not possible to determine whether it is better to have intense immersion experiences or to distribute the time spent in the communities over a more extended period of time. Examples of both were found among the included papers.

Different types of communities are involved in the programs reviewed. Most often they are located in the same region as the schools, but some schools have partnerships with communities farther away or even abroad. When international learning experiences, additional aspects, such as financial support, logistics, and language barriers, need to be considered. One program (Meili et al., 2011) offered the students a broad range of experiences (including 6 weeks in a rural remote community, two shifts per month in an urban student-run clinic, and 6 weeks in a rural hospital abroad).

Service learning was found to be the most commonly used educational approach. Several authors emphasize its different components, which basically encompass both elements of the term “service learning.” “Service” refers to the fact that a genuine collaboration with the community should be established. Community members should be involved at all stages of the training and should also benefit from the cooperation. It is an ethical obligation to focus on reciprocal benefits and to avoid the risk of students being involved in “social sightseeing” (Art et al., 2008). Examples of community benefits include direct help from community projects or support through advocacy for the community (e.g., students writing a letter to the editor [Dharamsi et al., 2010a] or presenting survey findings to local key decision makers [Clithero et al., 2013]). In addition, Dharamsi and colleagues

(2010a) stress taking a “social justice” approach and not a “charity” approach. This means that the focus should be not on providing direct service to the community members but on understanding and working to change the structural and institutional factors that contribute to health inequities. Therefore, the sustainability of the campus-community partnership is important. In one of the programs (Kruger et al., 2010), the organizers chose to bolster what the community was already doing “rather than to carve out a niche to address unmet needs and risk competing for scarce resources.” The “learning” component of service learning requires not just having students go into to the communities, but stimulating genuine learning among them. This encompasses defining learning goals from the outset, properly preparing students for the learning experience, and guiding them during the community experience. Moreover, reflection is an indispensable component of the training.

Many programs offered a mix of experiential and nonexperiential program components. Experiential learning components included, for instance, conducting community (health) needs assessment, developing and implementing a project or intervention, organizing educational sessions for community members, and caring for individual patients. Nonexperiential learning components included lectures, group discussions, workshops to build capacities, simulation experiences, reading assignments, online activities, presentations, and research projects. Generally, students valued the experiential component highly.

While service-learning experiences appear to be highly valued by educators and students, their effectiveness remains unclear. This observation is in line with the conclusions of Stallwood and Groh (2011) in their systematic review of the evidence on service learning in nursing education. The program evaluation and outcome measurements that are discussed in the present study are generally rather weak and involve considerable risk of various types of biases (e.g., based mainly on self-report, selection of students participating in the program, low numbers of participants, the Hawthorne effect, use of nonvalidated instruments). Moreover, very few papers take the community’s perspective into account and none assess long-term effects.

The papers rarely address recruitment of minority students for the programs. Among the included papers, only Parks and colleagues (2015) addressed this issue by establishing a program at four historically black colleges and universities. Although reflecting a slightly different issue, Clithero and colleagues (2013) report selecting a diverse group of high school seniors who were committed to practicing in New Mexico’s communities of greatest need.

Whether the programs reviewed could easily be replicated is difficult to answer. In many papers, crucial information needed to answer this question is lacking (this may be related partly to the word count restrictions journals

impose on authors). Nevertheless, several papers offer insight into the most important training components, and a few also describe the difficulties encountered (which may be valuable for future program development).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on this review, the following recommendations can be put forward:

-

With regard to the present study

- A further search for other papers to complete this study is needed. Additionally, contacting the authors of some of the most promising programs might be worthwhile.

-

With regard to further development of this type of learning

- Although available information is very limited, overall evaluation of the programs tends to be positive (especially based on qualitative data). This implies that there are arguments to be made for encouraging/favoring further promotion and implementation of these programs.

- Both components of “service learning” should be carefully incorporated into the training.

- An appropriate amount of student guidance should be offered. A good balance is necessary between providing information and guidance on the one hand and allowing for student autonomy and confrontations with real-life conditions on the other.

- Recommendations with regard to the ideal length of training are difficult to make based on the findings of this review. Nevertheless, experiences that are too brief may compromise the reciprocity of the benefits for students and the communities.

- As time constraints are often mentioned among the difficulties encountered, appropriate measures for dealing with this issue should be taken into account, where possible.

-

With regard to future research

- When introducing a new program, a well-considered evaluation protocol relying on solid research methods should be considered from the beginning.

- Efforts should be made to publish the results of this research, as they may inspire other authors. Detailed descriptions of the programs (including the difficulties that were encountered in establishing the program) are recommended.

- Valid and reliable evaluation instruments should be developed.

-

- All parties (students, trainers, and community members) should be involved in the evaluation process.

- Efforts to obtain data on outcomes and long-term effects should be encouraged. Questions of interest include Is there an impact of the program on students’ career choices? Is there an impact on the social determinants of health and on the community’s status? Do programs contribute to increased social accountability of institutions for health professional education? and How does the program affect the community’s health?

-

With regard to ethical considerations

- As vulnerable populations are directly involved in this type of education, ethical considerations are extremely important. They include, for instance, being careful not to reinforce power relations, as may be the case when upper-class students come to help minority populations. Solid support and preparation by experienced, ethically, and culturally sensitive persons, preferably both at the university and in the community, is recommended.

- Sustainability of the collaborations should be carefully considered. Interprofessional and intersectoral approaches may be most effective way to stimulate a sustainable community health impact.

ANNEX A-16: SELF-DESIGNED SCREENING TOOL

| EVALUATION PAPERS IOM STUDY | Paper (Number, Author, Year) |

| ………….……………………………………………………………… | |

| TYPE OF PAPER |

| Type | Full paper - Conference abstract - |

| Content | Research - Only descriptive - |

| PROGRAM |

| Name of school | |

| Location of school | |

| Name of program | |

| Location of training | |

| (which community) | |

| Duration of training: Total | |

| Duration of training: | |

| Community learning part | |

| Program in curriculum | Obligatory / Elective / Extracurricular |

| Participants: Level | Undergraduate students / Postgraduate students / Professionals |

| Participants: Type of | |

| health profession | |

| Participants: Number | |

| Start of program |

| Described Goal of Training |

| Educational approach | |

| Framework/model | |

| SDH explicit aim | Yes / No |

| Focus on SDH | Central / Marginal |

| References to SDH | |

| SDH discussed as outcome |

___________________

6 Part of this Annex A-1, Table A-1, a literature review summary, is available at http://www.nap.edu/catalog/21923.

| Content of Training (Components) |

| IF RESEARCH PAPER | ||

| Type | Quantitative / Qualitative / Mixed |

| Data | |

| Research topic | |

| Number of participants | |

| Main findings (if relevant and not in IOM questions) | |

| Strength of study - limitations |

| IOM QUESTIONS |

| Was education goal obtained? | |

| Was the program successful? | |

| Were there any difficulties? | |

| Might the training be replicated? | |

| Any information about the cost? | |

| Are there any anecdotes that may be included? | |

| Suggestions formulated by authors |

REFERENCES TO BE CHECKED: Yes / No

ESTEEMED VALUE FOR PRESENT STUDY:

REMARKS:

REFERENCES

Art, B., L. De Roo, S. Willems, and J. De Maeseneer. 2008. An interdisciplinary community diagnosis experience in an undergraduate medical curriculum: Development at Ghent University. Academic Medicine 83(7):657-683.

Bakshi, S., A. James, M. O. Hennelly, R. Karani, A. G. Palermo, A. Jakubowski, C. Ciccariello, and H. Atkinson. 2015. The human rights and social justice scholars program: A collaborative model for preclinical training in social medicine. Annals of Global Health 81(2):290-297.

Bell, M. L., and J. R. Buelow. 2014. Teaching students to work with vulnerable populations through a patient advocacy course. Nurse Educator 39(5):236-240.

Brown, B., P. C. Heaton, and A. Wall. 2007. A service-learning elective to promote enhanced understanding of civic, cultural, and social issues and health disparities in pharmacy. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 71(1):6-9.

Bussey-Jones, J. C., M. George, S. Schmidt, J. E. Bracey, M. Tejani, and S. D. Livingston. 2014. Welcome to the neighborhood: Teaching the social determinants of health. Journal of General Internal Medicine 29:S543-S544.

Clithero, A., R. Sapien, J. Kitzes, S. Kalishman, S. Wayne, B. Solan, L. Wagner, and V. Romero-Leggott. 2013. Unique premedical education experience in public health and equity: Combined BA/MD summer practicum. Creative Education 4(7A2):165-170.

De Los Santos, M., C. D. McFarlin, and L. Martin. 2014. Interprofessional education and service learning: A model for the future of health professions education. Journal of Interprofessional Care 28(4):374-375.

Dharamsi, S., N. Espinoza, C. Cramer, M. Amin, L. Bainbridge, and G. Poole. 2010a. Nurturing social responsibility through community service-learning: Lessons learned from a pilot project. Medical Teacher 32(11):905-911.

Dharamsi, S., M. Richards, D. Louie, D. Murray, A. Berland, M. Whitfield, and I. Scott. 2010b. Enhancing medical students’ conceptions of the canmeds health advocate role through international service-learning and critical reflection: A phenomenological study. Medical Teacher 32(12):977-982.

Ezeonwu, M., B. Berkowitz, and F. R. Vlasses. 2014. Using an academic-community partnership model and blended learning to advance community health nursing pedagogy. Public Health Nursing 31(3):272-280.

Feen-Calligan, H. 2008. Service-learning and art therapy in a homeless shelter. Arts in Psychotherapy 35(1):20-33.

Ierardi, F., and E. Goldberg. 2014. Looking back, looking forward: New masters-level creative arts therapists reflect on the professional impact of an interprofessional community health internship. Arts in Psychotherapy 41(4):366-374.

Jarrell, K., J. Ozymy, J. Gallagher, D. Hagler, C. Corral, and A. Hagler. 2014. Constructing the foundations for compassionate care: How service-learning affects nursing students’ attitudes towards the poor. Nurse Education in Practice 14(3):299-303.

Kassam, R., A. Estrada, Y. Huang, B. Bhander, and J. B. Collins. 2013. Addressing cultural competency in pharmacy education through international service learning and community engagement. Pharmacy 1(1):16-33.

Kelly, P. J. 2013. A framework for service learning in physician assistant education that fosters cultural competency. Journal of Physician Assistant Education 24(2):32-37.

Kruger, B. J., C. Roush, B. J. Olinzock, and K. Bloom. 2010. Engaging nursing students in a long-term relationship with a home-base community. Journal of Nursing Education 49(1):10-16.

Larson, K. L., M. Ott, and J. M. Miles. 2010. International cultural immersion: En vivo reflections in cultural competence. Journal of Cultural Diversity 17(2):44-50.

Loewenson, K. M., and R. J. Hunt. 2011. Transforming attitudes of nursing students: Evaluating a service-learning experience. Journal of Nursing Education 50(6):345-349.

Matejic, B., D. Vukovic, M. S. Milicevic, Z. T. Supic, A. J. Vranes, B. Djikanovic, J. Jankovic, and V. Stambolovic. 2012. Student-centred medical education for the future physicians in the community: An experience from Serbia. HealthMED 6(2):517-524.

Meili, R., D. Fuller, and J. Lydiate. 2011. Teaching social accountability by making the links: Qualitative evaluation of student experiences in a service-learning project. Medical Teacher 33(8):659-666.

Meurer, L. N., S. A. Young, J. R. Meurer, S. L. Johnson, I. A. Gilbert, S. Diehr, and Urban and Community Health Pathway Planning Council. 2011. The Urban and Community Health Pathway: Preparing socially responsive physicians through community-engaged learning. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 41(4):S228-S236.

Mudarikwa, R. S., J. A. McDonnell, S. Whyte, E. Villanueva, R. A. Hill, W. Hart, and D. Nestel. 2010. Community-based practice program in a rural medical school: Benefits and challenges. Medical Teacher 32(12):990-996.

O’Brien, M. J., J. M. Garland, K. M. Murphy, S. J. Shuman, R. C. Whitaker, and S. C. Larson. 2014. Training medical students in the social determinants of health: The Health Scholars Program at Puentes de Salud. Advances in Medical Education and Practice 5:307-314.

Ogenchuk, M., S. Spurr, and J. Bally. 2014. Caring for kids where they live: Interprofessional collaboration in teaching and learning in school settings. Nurse Education in Practice 14(3):293-298.

Parks, M. H., L. H. McClellan, and M. L. McGee. 2015. Health disparity intervention through minority collegiate service learning. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 26(1):287-292.

Rasmor, M., S. Kooienga, C. Brown, and T. M. Probst. 2014. United States nurse practitioner students’ attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs working with the uninsured. Nurse Education in Practice 14(6):591-597.

Sabo, S., J. de Zapien, N. Teufel-Shone, C. Rosales, L. Bergsma, and D. Taren. 2015. Service learning: A vehicle for building health equity and eliminating health disparities. American Journal of Public Health 105(Suppl. 1):S38-S43.

Schoon, P. M., B. E. Champlin, and R. J. Hunt. 2012. Developing a sustainable foot care clinic in a homeless shelter within an academic–community partnership. Journal of Nursing Education 51(12):714-718.

Seifer, S. D. 1998. Service-learning: Community-campus partnerships for health professions education. Academic Medicine 73(3):273-277.

Sharma, M.. 2014. Developing an integrated curriculum on the health of marginalized populations: Successes, challenges, and next steps. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 25(2):663-669.

Sheu, L., C. J. Lai, A. D. Coelho, L. D. Lin, P. Zheng, P. Hom, V. Diaz, and P. S. O’Sullivan. 2012. Impact of student-run clinics on preclinical sociocultural and interprofessional attitudes: A prospective cohort analysis. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 23(3):1058-1072.

Stallwood, L. G., and C. J. Groh. 2011. Service-learning in the nursing curriculum: Are we at the level of evidence-based practice? Nursing Education Perspectives 32(5):297-301.

Stanley, M. J. 2013. Teaching about vulnerable populations: Nursing students’ experience in a homeless center. Journal of Nursing Education 52(10):585-588.

Ward, S., M. Blair, F. Henton, H. Jackson, T. Landolt, and K. Mattson. 2007. Service-learning across an accelerated curriculum. Journal of Nursing Education 46(9):427-430.

Williams, B. C., J. S. Perry, A. J. Haig, P. Mullan, and J. Williams. 2012. Building a curricuum in global and domestic health disparities through a longitudinal mentored leadership training program. Journal of General Internal Medicine 27:S552.

This page intentionally left blank.