1

Introduction

Small businesses are an important driver of innovation and economic growth in the United States.1 Despite the challenges of changing global environments and the impacts of the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession, innovative small businesses continue to develop and commercialize new products for the market, improving the health and welfare of Americans while strengthening the nation’s security and competitiveness.2

Created in 1982 through the Small Business Innovation Development Act,3 the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program remains the nation’s largest innovation program for small business. The SBIR program offers competitive awards to support the development and commercialization of innovative technologies by small private-sector businesses.4 At the same time,

___________________

1 See Z. Acs and D. Audretsch, “Innovation in large and small firms: An empirical analysis,” The American Economic Review, 78(4):678-690, 1988. See also Z. Acs and D. Audretsch, Innovation and Small Firms, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991; E. Stam and K. Wennberg, “The roles of R&D in new firm growth,” Small Business Economics, 33:77-89, 2009; E. Fischer and A.R. Reuber, “Support for rapid-growth firms: A comparison of the views of founders, government policymakers, and private sector resource providers,” Journal of Small Business Management, 41(4):346-365, 2003; M. Henrekson and D. Johansson, “Competencies and institutions fostering high-growth firms,” Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 5(1):1-80, 2009.

2 See D. Archibugi, A. Filippetti, and M. Frenz, “Economic crisis and innovation: Is destruction prevailing over accumulation?” Research Policy, 42(2):303-314, 2013. The authors show that “the 2008 economic crisis severely reduced the short-term willingness of firms to invest in innovation” and also that it “led to a concentration of innovative activities within a small group of fast growing new firms and those firms already highly innovative before the crisis.” They conclude that “the companies in pursuit of more explorative strategies towards new product and market developments are those to cope better with the crisis.”

3 Small Business Innovation Development Act of 1982, P.L. 97-219, July 22, 1982.

4 SBIR awards can be made as grants or as contracts. Grants do not require the awardee to provide an agreed deliverable (for contracts this is often a prototype at the end of Phase II). Contracts are also governed by federal contracting regulations, which are considerably more demanding from the small business perspective. Historically, all Department of Defense (DoD) and NASA awards have been contracts, all National Science Foundation (NSF) and most National Institutes of Health (NIH) awards have been grants, and the Department of Energy (DoE) has used both vehicles.

the program provides government agencies with technical and scientific solutions that address their different missions.

Seeking to bridge the gap between basic science and commercialization of resulting innovations, the Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) program, created in 1992 by the Small Business Research and Development Enhancement Act of 19925 seeks to expand joint venture opportunities for small businesses and nonprofit research institutions. Under STTR, a small business receiving an award must collaborate formally with a research institution.

Both the SBIR and STTR programs consist of three phases:

- Phase I provides limited funding (up to $100,000 prior to the 2011 reauthorization and up to $150,000 thereafter) for feasibility studies.

- Phase II provides more substantial funding for further research and development (typically up to $750,000 prior to 2012 and $1 million after the 2011 reauthorization).6

- Phase III reflects commercialization without providing access to any additional SBIR/STTR funding, although funding from other federal government accounts is permitted.

The SBIR program has four congressionally mandated goals: (1) to stimulate technological innovation, (2) to use small business to meet federal research and development (R&D) needs, (3) to foster and encourage participation by minority and disadvantaged persons in technological innovation, and (4) to increase private-sector commercialization derived from federal research and development.7 The goals for the STTR program are to (1) stimulate technological innovation, (2) foster technology transfer through cooperative R&D between small businesses and research institutions, and (3) increase private-sector commercialization of innovations derived from federal R&D.8 Each of the research agencies has sought to pursue these goals in administering their SBIR and STTR programs, utilizing the administrative flexibility built into the general program to address their unique mission needs.9 Agencies with SBIR programs include the Department of Agriculture,

___________________

5 Small Business Research and Development Enhancement Act, P.L. 102-564, Sec. 2941, Oct. 28, 1992.

6 All resource and time constraints imposed by the program are somewhat flexible and are addressed by different agencies in different ways. For example, NIH and to a much lesser degree DoD have provided awards that are much larger than the standard amounts, and NIH has a tradition of offering no-cost extensions to see work completed on an extended timeline.

7 Small Business Innovation Development Act of 1982, P.L. 97-219, Sec. 881, July 22, 1982.

8 Small Business Administration, “About STTR,” https://www.sbir.gov/about/about-sttr, accessed July 9, 2015. Only the first two objectives are embedded in the authorizing legislation, although there is little controversy about the importance of the third, which appears to have been added by the Small Business Administration (SBA) in drafting its governing Policy Guidance for the program.

9 The committee commended this flexibility in its 2008 assessment of the SBIR program. See Finding C, National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, p. 59.

Department of Commerce, Department of Defense (DoD), Department of Education, Department of Energy (DoE), Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Department of Homeland Security, Department of Transportation, Environmental Protection Agency, NASA, and the National Science Foundation (NSF). Of these, DoD, NSF, DoE, DHHS, and NASA also have STTR programs.

At DoE, differences between the SBIR and STTR programs are summarized in the guidance document provided for potential applicants:

- STTR requires a formal collaboration between the small business concern (SBC) and a research institution (RI). The latter include colleges, universities, federal R&D laboratories, and other nonprofit research organizations.

- SBIR requires that the Principal Investigator (PI) be primarily employed by the SBC; STTR permits the PI to work only part time at the SBC, which, in turn, permits university faculty members to retain their faculty positions while acting as PI.

- SBIR requires that at least two-thirds of the Phase I and at least one-half of the Phase II R&D be conducted by the SBC; for both Phase I and II, STTR requires the SBC to perform at least 40 percent of the research and the RI at least 30 percent.10

As discussed in Chapter 2, DoE effectively operates SBIR and STTR as a unified program: it releases a unified solicitation, and companies can apply simultaneously for SBIR and STTR funding.

In fiscal year (FY) 2015, across DoE, 18 percent of Phase I SBIR/STTR applications resulted in an award, making it a highly competitive program. Also in FY 2015, 60 percent of Phase II applications were successful.11 As a result, about 11 percent of DoE Phase I applications can be expected to result in a Phase II award. Before the 2011 reauthorization, Phase II awards could be awarded only to projects that had successfully completed Phase I, but after the reauthorization, Phase II awards could be awarded without meeting that requirement.

Over time, through a series of reauthorizations described in the pages that follow, SBIR/STTR legislation has required those federal agencies with extramural R&D budgets in excess of $100 million to set aside a growing percentage of their budgets for the SBIR program, and those with extramural R&D budgets in excess of $1 billion to set aside a growing percentage of their budgets for the STTR program (see Table 1-2). By FY 2012, the 11 federal agencies administering the SBIR/STTR programs were disbursing $2.4 billion

___________________

10 Manny Oliver, “DOE’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs,” DoE Webinar, December 4, 2015, p. 6.

11 Data provided by DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office.

TABLE 1-1 Agencies Currently Participating in the SBIR and STTR Programs

| Agency | SBIR Participant | STTR Participant |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Agriculture | X | |

| Department of Commerce | X | |

| Department of Defense | X | X |

| Department of Education | X | |

| Department of Energy | X | X |

| Department of Health and Human Servicesa | X | X |

| Department of Homeland Security | X | |

| Department of Transportation | X | |

| Environmental Protection Agency | X | |

| National Aeronautics and Space Administration | X | X |

| National Science Foundation | X | X |

a The Institutes and Centers at the National Institutes of Health; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Food and Drug Administration (FDA); and the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) each operates its own SBIR and STTR programs.

SOURCE: Small Business Administration.

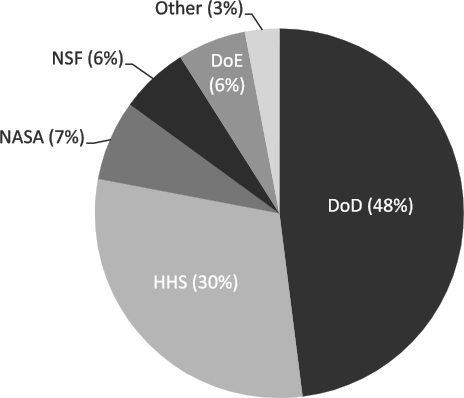

a year.12 As shown in Figure 1-1, 5 agencies administer greater than 96 percent of SBIR/STTR funds: Department of Defense (DoD), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) particularly the National Institutes of Health [NIH]), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), National Science Foundation (NSF), and Department of Energy (DoE). Aggregate award amounts for the five largest agencies for FY 2012 are provided in Table 1-2.

In December 2011, Congress reauthorized the SBIR/STTR programs for an additional 6 years,13 with a number of important modifications. Many of these modifications—for example, changes in standard award size—were consistent with or followed recommendations made in a 2008 National Research Council (NRC)14 report on the SBIR program, a study mandated as part of the program’s 2000 reauthorization.15 The 2011 reauthorization also called for further studies by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.16

___________________

12 Small Business Association, SBIR/STTR annual report, http://www.sbir.gov/, accessed July 2015. FY2012 is the most recent year for which SBA publishes comparative data across agencies.

13 Sec. 5137 of P.L. 112-81.

14 Effective July 1, 2015, the institution is called the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. References in this report to the National Research Council or NRC are used in an historic context identifying programs prior to July 1, 2015.

15 National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program. The National Research Council’s first-round assessment of the SBIR program was mandated in the SBIR Reauthorization Act of 2000, P.L. Law 106-554, Appendix I-H.R. 5667, Sec. 108.

16 The National Defense Reauthorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012, P.L. 112-81, Sec. 5137.

TABLE 1-2 SBIR/STTR Funding by the Five Principal Funding Agencies, FY 2012

| Agency | Sum of Award Amounts (Dollars) |

|---|---|

| Department of Defense | 1,013,041,252 |

| Department of Energy | 201,954,290 |

| Department of Health and Human Servicesa | 774,065,517 |

| National Aeronautics and Space Administration | 159,122,575 |

| National Science Foundation | 130,236,977 |

| Total | 2,278,420,611 |

a The Institutes and Centers at the National Institutes of Health; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Food and Drug Administration (FDA); and the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) each operates its own SBIR and STTR programs.

SOURCE: SBA awards database, https://www.sbir.gov/sbirsearch/award/all, accessed January 6, 2016.17

NOTE: The Institutes and Centers at the National Institutes of Health; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Food and Drug Administration (FDA); and the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) each operates its own SBIR and STTR programs.

SOURCE: Small Business Administration, FY 2012 SBIR/STTR annual report, http://www.sbir.gov, accessed January 4, 2016.

___________________

17 It is a matter of some concern that SBA has not updated the SBIR/STTR annual reports available to the public. All of the agencies have reported FY 2015 data, and it is unclear why SBA has not provided what are relatively simple reports in a timely manner.

The National Academies’ first-round assessment resulted in 11 publications including the 2008 report referenced above. (See Box 1-1 for a listing of the 11 publications).

This introduction provides general context for analysis of the program developments and transitions described in the remainder of the report. The first section of the introduction provides an overview of the history and structure of the SBIR and STTR programs across the federal government. This is followed

by a summary of the major changes mandated through the 2011 reauthorization and the subsequent Small Business Administration (SBA) Policy Directive; a review of the program’s advantages and limitations, in particular the challenges faced by entrepreneurs using (and seeking to use) the program and by agency officials running the program; and a summary of the technical challenges facing this assessment and our recommended solutions to those challenges.

PROGRAM HISTORY AND STRUCTURE18

A review of the programs’ origins and legislative history provides context to its place in the U.S innovation landscape. During the 1980s, the perceived decline in U.S. competitiveness due to Japanese industrial growth in sectors traditionally dominated by U.S. firms—autos, steel, and semiconductors—led to concerns about future economic growth in the United States.19 A key concern was the perceived failure of American industry “to translate its research prowess into commercial advantage.”20 Although the United States enjoyed dominance in basic research—much of which was federally funded—applying this research to the development of innovative products and technologies remained a challenge. As the great corporate laboratories of the post-war period were buffeted by change, new models such as the cooperative model utilized by Japanese keiretsu seemed to offer greater sources of dynamism and more competitive firms.

At the same time, new evidence emerged to indicate that small businesses were an increasingly important source of both innovation and job creation.21 This evidence reinforced recommendations from federal commissions dating back to the 1960s; that is, federal R&D funding should

___________________

18 Parts of this section are based on the National Academies’ previous report on the NIH SBIR program: National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the National Institutes of Health, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009.

19 See J. Alic, “Evaluating competitiveness at the office of technology assessment,” Technology in Society, 9(1):1-17, 1987, for a review of how these issues emerged and evolved within the context of a series of analyses at a Congressional agency.

20D.C. Mowery, “America’s industrial resurgence (?): An overview,” in D.C. Mowery, ed., U.S. Industry in 2000: Studies in Competitive Performance, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1999, p. 1. Other studies highlighting poor economic performance in the 1980s include M.L. Dertouzos et al., Made in America: The MIT Commission on Industrial Productivity, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1989; and O. Eckstein, DRI Report on U.S. Manufacturing Industries, New York: McGraw Hill, 1984.

21 See S.J. Davis, J. Haltiwanger, and S. Schuh, Small Business and Job Creation: Dissecting the Myth and Reassessing the Facts, Working Paper No. 4492, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1993. According to Per Davidsson, these methodological fallacies, however, “ha [ve] not had a major influence on the empirically based conclusion that small firms are overrepresented in job creation.” See P. Davidsson, “Methodological concerns in the estimation of job creation in different firm size classes,” Working Paper, Jönköping International Business School, 1996.

provide more support for innovative small businesses (which was opposed by traditional recipients of government R&D funding).22

Early-stage financial support for high-risk technologies with commercial promise was first advanced within an agency by Roland Tibbetts at NSF. In 1976, Mr. Tibbetts advocated for shifting some NSF funding to innovative technology-based small businesses. NSF adopted this initiative first, and after a period of analysis and discussion, the Reagan administration supported an expansion of this initiative across the federal government. Congress then passed the Small Business Innovation Research Development Act of 1982, which established the SBIR program.

Initially, the SBIR program required agencies with extramural R&D budgets in excess of $100 million23 to set aside 0.2 percent of their funds for SBIR. Program funding totaled $45 million in the program’s first year of operation (1983). Over the next 6 years, the set-aside grew to 1.25 percent.24

The SBIR Reauthorizations of 1992 and 2000

The SBIR program approached reauthorization in 1992 amid continued worries about the ability of U.S. firms to commercialize inventions (see Box 1-2). Finding that “U.S. technological performance is challenged less in the creation of new technologies than in their commercialization and adoption,” the National Academies recommended an increase in SBIR funding as a means to improve the economy’s ability to adopt and commercialize new technologies.25

The Small Business Research and Development Enhancement Act (P.L. 102-564) reauthorized the SBIR program until September 30, 2000, and doubled the set-aside rate to 2.5 percent. The legislation also more strongly emphasized the need for commercialization of SBIR-funded technologies.26 Legislative language explicitly highlighted commercial potential as a criterion for awarding SBIR contracts and grants.

___________________

22 For an overview of the origins and history of the SBIR program, see G. Brown and J. Turner, “The federal role in small business research,” Issues in Science and Technology, Summer 1999, pp. 51-58.

23 That is, those agencies spending more than $100 million on research conducted outside agency laboratories.

24 Additional information regarding SBIR’s legislative history can be accessed from the Library of Congress. See http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d097:SN00881:@@@L.

25 See National Research Council, The Government Role in Civilian Technology: Building a New Alliance, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1992, p. 29.

26 Small Business Research and Development Enhancement Act, P.L. 102-564, Sec. 2941, Oct. 28, 1992. See also R. Archibald and D. Finifter, “Evaluation of the Department of Defense Small Business Innovation Research program and the Fast Track Initiative: A balanced approach,” in National Research Council, The Small Business Innovation Research Program: An Assessment of the Department of Defense Fast Track Initiative, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000, pp. 211-250.

At the same time, Congress expanded the SBIR program’s purposes to “emphasize the program’s goal of increasing private sector commercialization developed through federal research and development and to improve the federal government’s dissemination of information concerning the small business innovation, particularly with regard to woman-owned business concerns and by socially and economically disadvantaged small business concerns.”27

Established by the Small Business Technology Transfer Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-564, Title II), the STTR program was reauthorized until 2001 by the Small Business Reauthorization Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-135) and reauthorized again until September 30, 2009, by the Small Business Technology Transfer Program Reauthorization Act of 2001 (P.L. 107-50).

As explained below, the SBIR/STTR Reauthorization Act of 2011 included a number of changes to the SBIR/STTR programs, including increases in the set-asides over the next 6 years and expanded eligibility for STTR awardees to take part in technical assistance programs.

The 2011 SBIR/STTR Reauthorization

The anticipated 2008 reauthorization was delayed in large part by a disagreement between long-time program participants and their advocates in the small business community and proponents of expanded access for venture-backed firms, particularly in biotechnology where proponents argued that the

___________________

27 Small Business Research and Development Enhancement Act, P.L. 102-564, Sec. 2941, Oct. 28, 1992.

standard path to commercial success includes venture funding at some point.28 Other issues were also difficult to resolve, but the conflict over participation of venture-backed companies dominated the process29 following an administrative decision to exclude these firms more systematically.30

After a much extended discussion, passage of the National Defense Act of December 2011 reauthorized the SBIR and STTR programs through FY 2017.31 The new law maintained much of the core structure of both programs but made some important changes, which were to be implemented via the SBA’s subsequent Policy Guidance.32

The eventual compromise on the venture funding issue allowed (but did not require) agencies to award up to 25 percent at NIH, DoE, and NSF, or 15 percent at the other awarding agencies of their SBIR grants or contracts to firms that benefit from private, venture capital investment. It is too early in the implementation process to gauge the impact of this change.

The reauthorization made changes in the SBIR program that were recommended in prior National Academies reports.33 These included the following:

- Increased award size limits

- Expanded program size

- Enhanced agency flexibility—for example for Phase I awardees from other agencies to be eligible for Phase II awards or to add a second Phase II

- Improved incentives for the utilization of SBIR technologies in agency acquisition programs

- Explicit requirements for better connecting prime contractors with SBIR awardees

- Substantial emphasis on developing a more data-driven culture, which has led to several major reforms, including the following:

- adding numerous areas of expanded reporting

- extending the National Academies’ evaluation program

___________________

28D.C. Specht, “Recent SBIR extension debate reveals venture capital influence,” Procurement Law, 45:1, 2009.

29W.H. Schacht, “The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program: Reauthorization efforts," Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, 2008.

30A. Bouchie, “Increasing number of companies found ineligible for SBIR funding,” Nature Biotechnology, 21(10):1121-1122, 2003.

31 SBIR/STTR Reauthorization Act of 2011, P.L. 112-81, Dec. 31, 2011.

32 See SBA post, S. Greene, “Implementing the SBIR and STTR Reauthorizations: Our Plan of Attack,” February 21, 2012, http://www.sbir.gov/news/implementing-sbir-and-sttr-reauthorizationour-plan-attack.

33 See Appendix B for a list of the major changes to the SBIR program resulting from the 2011 Reauthorization Act. For a report from the first-round assessment focused specifically on venture funding, see National Research Council, Venture Funding and the NIH SBIR Program, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009.

-

- adding further evaluation, such as by the Government Accountability Office and Comptroller General

- tasking the SBA with creating a unified platform for the collection of data

- Expanded management resources (through provisions permitting use of up to 3 percent of program funds for [defined] management purposes)

- Expanded commercialization support (through provisions providing companies with direct access to commercialization support funding and through approval of the approaches piloted in Commercialization Pilot Programs)

- Options for agencies to add flexibility by developing other pilot programs—for example, to allow awardees to skip Phase I and apply for a Phase II award directly or for DoE to support a new Phase 0 pilot program

The reauthorization also made changes that were not mentioned in previous reports of the National Academies. These included the following:

- Expansion of the STTR program

- Limitations on agency flexibility—particularly in the provision of larger awards

- Introduction of commercialization benchmarks for companies, which must be met if companies are to remain in the program. These benchmarks are to be established by each agency.

Other clauses of the legislation affect operational issues, such as the definition of specific terms (such as “Phase III”), continued and expanded evaluation by the National Academies, mandated reports from the Comptroller General on combating fraud and abuse within the program, and protection of small firms’ intellectual property within the program.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH ON SBIR

Prior to the National Academies’ first-round assessment, there had been few internal assessments of the agency programs, and external studies, most notably by the General Accounting Office and the SBA, focused on specific aspects or components of the SBIR and STTR programs.34 The academic

___________________

34 An important step in the evaluation of the program has been to identify existing evaluations of the program. These include U.S. Government Accounting Office, Federal Research: Small Business Innovation Research Shows Success But Can Be Strengthened, Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office, 1992; and U.S. Government Accounting Office, Evaluation of Small Business Innovation Can Be Strengthened, Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office,

literature on SBIR was also limited,35 except for an assessment in the 1990s by Joshua Lerner of the Harvard Business School who found “that SBIR awardees grew significantly faster than a matched set of firms over a ten-year period.”36

To help fill this assessment gap and to learn about a large, relatively under-evaluated program, the NRC’s Committee for Government-Industry Partnerships for the Development of New Technologies (GIP, which preceded the NRC’s first-round congressionally mandated study of the SBIR) convened a workshop to discuss the SBIR program’s history and rationale, review existing research, and identify areas for further research and program improvements.37 In addition, in its report on the SBIR Fast Track Program at the Department of Defense, the GIP committee found that the SBIR program contributed to mission goals by funding “valuable innovative projects.”38 It concluded that a significant number of these projects would not have been undertaken absent SBIR funding39 and that DoD’s Fast Track program encouraged the commercialization of new technologies40 and the entry of new firms into the program.41 The GIP committee also found that the SBIR program improved both the development and utilization of human capital and the diffusion of technological knowledge.42 Case studies provided some evidence that the knowledge and human capital generated by the SBIR program have positive economic value, which spills over into other firms through the movement of people and ideas.43 Furthermore, by acting as a “certifier” of promising new technologies, SBIR awards encourage further private-sector investment in an award-winning firm’s technology.44

It may be suggested that private sources of financing, such as early-stage seed capital firms and venture capital firms, can meet the need that is met by SBIR/STTR. However, both theoretical and empirical work on the process of innovation suggests that the private sector alone tends to underinvest in early-stage, high-risk innovation. Venture capital firms, early-stage seed companies

___________________

1999. There is also a 1999 unpublished SBA study on the commercialization of SBIR that surveys Phase II awards from 1983 to 1993 among non-DoD agencies.

35 Early examples of evaluations of the SBIR program include S. Myers, R. L. Stern, and M. L. Rorke, A Study of the Small Business Innovation Research Program, Lake Forest, IL: Mohawk Research Corporation, 1983; and Price Waterhouse, Survey of Small High-tech Businesses Shows Federal SBIR Awards Spurring Job Growth, Commercial Sales, Washington, DC: Small Business High Technology Institute, 1985.

36 See J. Lerner, “The government as venture capitalist: The long-run effects of the SBIR program,” Journal of Business, 72(3), 1999.

37 See National Research Council, The Small Business Innovation Research Program: Challenges and Opportunities, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1999.

38 National Research Council, An Assessment of the DoD SBIR Fast Track Initiative. See Chapter III: Recommendations and Findings, p. 32.

39 Ibid, p. 32.

40 Ibid, p. 33.

41 Ibid, p. 34.

42 Ibid, p. 33.

43 Ibid, p. 33.

44 Ibid, p. 33.

and other private financing sources tend to delay their investments until technical and business risks have been reduced. Venture capital funding waxes and wanes, and none of these are substitutes for SBIR/STTR.45 The fact that SBIR/STTR programs are the subject of multiple congressional objectives beyond commercialization only increases the likelihood that private funding sources are not analogous to SBIR and STTR.

THE ROUND-ONE STUDY OF SBIR

The 2000 SBIR reauthorization mandated that the NRC complete a comprehensive assessment of the SBIR program.46 This assessment of the SBIR programs at DoD, NIH, NASA, NSF, and DoE began in 2002 and was conducted in three steps. As a first step, the committee authoring this study developed a research methodology47 and gathered information about the program by convening workshops where officials at the relevant federal agencies described their program operations, challenges, and accomplishments. These meetings highlighted the important differences in agency goals, practices, and evaluations. They also served to describe the evaluation challenges that arise from the diversity in program objectives and practices.48

The committee implemented the research methodology during the second step. As set out in the methodology, multiple data collection modalities were deployed. These included the first large-scale survey of SBIR recipients. Case studies of a wide variety of SBIR firms were also developed. The committee then evaluated the results and developed the findings and recommendations presented in this report for improving the effectiveness of the SBIR program. It is important to stress that the respondents to the survey represented a subset of all awardees, and is biased towards the opinions of those who did respond.49

During the third step, the committee reported on the program through a series of publications in 2004-2009: five individual volumes on the five major funding agencies and an additional overview volume titled An Assessment of the SBIR Program.50 Together, these reports provided the first detailed and comprehensive review of the SBIR program and, as noted above, served as an important input into SBIR reauthorization prior to December 2011 (see Box 1-1).

___________________

45Lewis Branscomb, Kenneth Morse, and Michael Roberts, Managing Technical Risk and Understanding Private Sector Decision Making on Early Stage Technology-based Projects, NIST GCR 00-787, April 2000.

46 SBIR Reauthorization Act of 2000, P.L. 106-554, Appendix I-H.R. 5667, Sec. 108.

47National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2004.

48 Adapted from National Research Council, SBIR: Program Diversity and Assessment Challenges, Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2004.

49 Averaged survey response data is reported to the nearest whole number.

50 National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program.

THE CURRENT, SECOND-ROUND STUDY: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

The set of reports from the National Academies’ first-round study of the SBIR program found that the program was, overall, “sound in concept and effective in practice.”51 Furthermore, in its review of the DoE SBIR program, the committee concluded, “The DoE SBIR program is making significant progress in achieving the congressional goals for the program.”52 The current study, described in the Statement of Task in Box 1-3, provides a second snapshot to measure the program’s progress against its legislative goals.

This volume partially addresses the Statement of Task. It is supplemented by a number of workshops and other publications (See Box 1-4). For example, the committee convened workshops on the participation of women and minorities in SBIR/STTR (February 2013), the evolving role of university participation in the program (February 2014), the relationship between state innovation programs and SBIR (October 2014—see Box 1-5), the STTR program (May 2015), the economics of entrepreneurship in relation to SBIR (June 2015), and the challenge of commercialization of SBIR and STTR technologies (April 2016). The National Academies also published a report on Innovation, Diversity, and Success in the SBIR/STTR Programs, based on the 2013 workshop.

The current volume is focused on updating the National Academies’ 2009 assessment of the DoE SBIR program, by updating data, providing new descriptions of recent programs and developments, and providing fresh company case studies. Guided by this Statement of Task, the committee sought answers to questions such as the following:

- Are there initiatives and programs within DoE that have made a significant difference to outcomes and in particular to the commercialization of SBIR-/STTR-funded technologies?

- Can they be replicated and expanded?

- What are the main barriers to meeting Congressional objectives more fully?

- What program adjustments would better support commercialization?

- Are there tools that would expand utilization of the SBIR and STTR by woman- and minority-owned firms and participation by female and minority principal investigators?

- Can links with universities be improved? In what ways and to what effect?

- Are there aspects of the program that make it less attractive to small firms? Could they be addressed?

___________________

51 Ibid., p. 54.

52National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program at the Department of Energy, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2008, p. 4.

- What can be done to expand access in underserved states while maintaining the competitive character of the program?

- Can the program generate better data on both process and outcomes and use those data to fine-tune program management?

STUDY METHODOLOGY

The SBIR/STTR programs are unique in terms of scale and mission focus. In addition, the evidence suggests that there are no truly comparable programs in the United States, and those in other countries operate in such different ways that their relevance is limited.53 Thus, it is difficult to identify comparable programs to SBIR/STTR against which to benchmark their results.

Assessing the DoE SBIR/STTR programs is challenging for other reasons as well. Unlike DoD and NASA, SBIR/STTR awards at DoE—although they may help to generate tools and capabilities for agency use—have their primary function as supporting technologies that will be adopted outside the

___________________

53 See National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, workshop on “Learning from Each Other: U.S. European Perspectives on Small Business Innovation Programs,” Washington, DC, March 19, 2015.

agency, largely in the private sector. Thus success cannot be measured by internal sales of product to the agency alone.

The DoE SBIR/STTR programs are highly centralized in terms of management, but it is highly decentralized in terms of agency uses of the program and the kinds of topics that are funded. Although the SBIR/STTR Program Office sets policy, closely manages the topic development, solicitation, application, and award processes, and provides ongoing support for contracts and commercialization, each program area determines award funding separately. Program areas may have different views of the program and different approaches to their responsibilities. Therefore, generalizations about the DoE SBIR/STTR programs must be made with care.

Focus on Legislative Objectives

It is important to note at the outset that this volume—and this study—do not seek to provide a comprehensive review of the value of the SBIR/STTR programs, in particular measured against other possible alternative uses of federal funding. Such a review is beyond the committee’s scope. Rather, the committee’s work is focused on assessing the extent to which the DoE SBIR/STTR programs have met the congressional objectives set for the programs, in particular whether recent initiatives have improved program outcomes, and to provide recommendations for further improvements to the programs.54

Therefore, as in the first-round study, the objective of this second-round study is “not to consider if SBIR should exist or not”—Congress and the President have already decided affirmatively on this question, most recently in the 2011 reauthorization of the program.55 Rather, this study is charged with “providing assessment-based findings of the benefits and costs of SBIR [and STTR]. . . to improve public understanding of the program, as well as recommendations to improve the program’s effectiveness.” As with the first-round committee, this committee “will not seek to compare the value of one area with other areas; this task is the prerogative of the Congress and the Administration acting through the agencies. Instead, the study is concerned with the effective review of each area.”56

Defining Commercialization

Among the varied congressional objectives for the SBIR/STTR programs described above, measuring commercialization offers practical and

___________________

54 These limited objectives are consistent with the methodology developed by the committee. See National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology.

55 National Defense Authorization Act of 2012 (NDAA) HR.1540, Title LI.

56 National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology.

definitional challenges. As described in Chapter 5, several different definitions of commercialization can be used to discuss the SBIR/STTR programs. The committee concluded that it is important to use more than one definition. For example, a simple measure of the percentage of funded projects that reach the marketplace is not a conclusive indicator of commercial success.

In the private sector, commercial success over the long term requires profitability. However, in the short term, the path to successful commercialization can involve many different aspects of commercial activity, from product rollout to licensing to patenting to acquisition. Even during new product rollout, companies often do not generate immediate profits. In this

report the committee uses multiple metrics to measure commercial activity (see Chapter 5).

Quantitative Assessment Methods

More practically, several issues relate to the application of quantitative assessment methods, including decisions about which kinds of program participants should be targeted for survey deployment, the number of responses that are appropriate, selection bias, nonresponse bias, the design and implementation of survey questionnaires, and the level of statistical evidence required for drawing conclusions in this case. These and other issues were discussed at a workshop described in a 2004 report.57 In addition, as noted above, a peer-reviewed report on study methodology completed by the first-round committee provided the baseline for the initial study and for follow-on studies—including this one.58

Survey Development

For the current study, a survey of SBIR and STTR award recipients was developed and deployed in 2014, a necessity given DoE’s decision to not provide quantitative outcomes data on privacy grounds. This survey was based closely on previous surveys, particularly the 2005 survey that focused exclusively on SBIR, but nonetheless it included significant improvements.59 The description of the survey and improvements, including a discussion of the survey outreach and response, are documented in Appendix A of this report. Most notably, the committee made an ambitious but ultimately unsuccessful effort to develop a comparison group to provide context and a benchmark for analyzing results (this effort is also discussed in Appendix A).

The 2014 Survey developed for this assessment delves more deeply into the demographics of the program. It also includes questions about the role of agency liaisons, who deal with contract operations and thereby provide a link between individual projects and DoE. Furthermore, it provides unique opportunities to collect qualitative views on the program and recommendations for improvement from recipients. The survey was deployed from December 2014 to April 2015 and generated 269 responses from DoE Phase II SBIR/STTR award recipients. It is an important component of the research conducted for this volume.

___________________

57 National Research Council, The Small Business Innovation Research Program: Program Diversity and Assessment Challenges.

58 National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology.

59 The survey carried out as part of this study was administered in 2014, and the survey completed as part of the National Academies’ first-round assessment of SBIR was administered in 2005. In this volume, all survey references are to the 2014 survey unless noted otherwise.

The committee chose to focus the survey on Phase II awards rather than Phase I awards because Phase II-funded projects are expected to have business plans and to have progress toward commercialization. Thus, it is reasonable to expect a survey based on Phase II to show more evidence of commercial activity than one based on Phase I or a combination of both phases.60 The focus on Phase II awards reflects the effects of a “weeding out” of projects which were not pursued by the companies for further SBIR/STTR funding. It also reflects the effects of a “weeding out” of projects which were deemed not worthy of additional funding by the SBIR/STTR funding process in cases where the Phase I work provided the answer being sought by the agency. The focus on Phase II seems reasonable given the interest in commercialization.

Appendix A provides a detailed discussion of the issues related to quantitative methodologies, a review of potential biases, and a list of the challenges of tracking commercial outcomes.61 The committee recognizes that there are significant limitations on the conclusions that can be drawn from this quantitative assessment, and this recognition is reflected in the wording of the findings and recommendations (Chapter 8).62 Limitations include the lack of a randomly drawn comparison group, likely biases in the survey results, and a focus only on Phase II awards. At the same time, drawing on quantitative analysis is a crucial component of the overall study, particularly given the need to identify and assess outcomes that are only to be found by querying individual projects and participating companies.

A Complement of Approaches

Partly because of these limitations, the committee stresses the importance of utilizing a complement of research modalities.63 Although quantitative assessment represents the bedrock of the committee’s research and provides insights and evidence that could not be generated through any other modality, it is, in and of itself, insufficient to address the multiple questions

___________________

60 In a working paper, Sabrina Howell employs regression discontinuity analysis to examine the impact of DoE SBIR awards. Utilizing application data from DoE, she compared firms just above and below the cutoff for receiving an award. She found that receipt of a Phase I award “approximately doubles” the chance of later receiving VC funding, increases patenting, and is associated with greater commercialization. Phase II awards, on the other hand, she found to have “tiny or negative effects on VC finance,” limited impact on patents, and no effect on reaching revenue. Howell’s data were limited to SBIR awards in the EERE and the Fossil Energy offices and included applicants over a longer time period. Also, Phase II awards require a significant length of time for companies to realize outcomes. Sabrina Howell, “DOE SBIR Evaluation: Impact of Small Grants on Subsequent Venture Capital Investment, Patenting, and Achieving Revenue,” Paper presented at the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Workshop on the Economics of Entrepreneurship, June 29, 2015.

61 Panel III of the committee’s April 12, 2016, workshop on “SBIR/STTR and the Commercialization Challenge” focused specifically on tracking SBIR/STTR commercialization outcomes.

62 For further discussion of potential sources of survey bias, see boxes 5-1 and A-1.

63 National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology.

posed in this analysis. Consequently, the committee undertook a series of additional activities:

- Case studies. The committee conducted in-depth case studies of 12 DoE SBIR/STTR award recipients. These companies were geographically and demographically diverse, funded by different program areas at DoE, focused on different kinds of technologies, and at different stages of the company lifecycle. Lessons learned from the case studies are described in Chapter 7, and the cases themselves are included as Appendix E.

- Workshops. The committee conducted workshops, including workshops to discuss the participation of women and minorities in SBIR/STTR, the role of universities in SBIR/STTR, and the challenge of commercializing SBIR/STTR technologies,64 to allow stakeholders, agency staff, and academic experts to provide insights into program operations, as well as to identify issues that should be addressed.

- Analysis of agency data. As appropriate, the committee analyzed and included data from DoE that cover various aspects of SBIR/STTR activities.

- Open-ended responses from SBIR/STTR recipients. For the first time, the committee collected textual responses in the survey. The comments received from 192 recipients are addressed in Chapter 7.

- Agency consultations. The committee engaged in discussions with agency staff about the operation of their programs and the challenges they face.

- Literature review. Since the start of the committee’s research in this area, a number of academic and policy papers have been published addressing various aspects of the SBIR/STTR programs, many drawing from the survey and other data made available by the National Academies. In addition, other organizations—such as the Government Accountability Office—have reviewed specific parts of the SBIR/STTR programs. The committee has incorporated references to their work, where useful, into its analysis. The committee also

___________________

64 Workshops convened by the committee as part of the overall analysis include NASA Small Business Innovation Research Program Assessment: Second Phase Analysis, January 28, 2010; Early-Stage Capital in the United States: Moving Research Across the Valley of Death and the Role of SBIR, April 16, 2010; Early-Stage Capital for Innovation—SBIR: Beyond Phase II, January 27, 2011; NASA’s SBIR Community: Opportunities and Challenges, June 21, 2011; Innovation, Diversity, and Success in the SBIR/STTR Programs, February 7, 2013; Commercializing University Research: The Role of SBIR and STTR, February 5, 2014; SBIR/STTR & the Role of States Programs, October 7, 2014; Workshop on the Small Business Technology Transfer Program, May 1, 2015; Economics of Entrepreneurship, June 29, 2015; and SBIR/STTR and the Commercialization Challenge, April 12, 2016. Each of these workshops was held in Washington, DC.

convened a workshop to learn more about new academic analysis of SBIR and STTR.65

Data Sources and Limitations

Multiple research modalities are especially important because limitations still exist in the data collected for the SBIR/STTR programs. As described in Chapter 5, DoE has not made its outcomes data available to the National Academies, which means that the National Academies’ 2014 Survey provides the only available quantitative data on SBIR/STTR outcomes and processes at DoE.

Cooperation with DoE

The committee received substantial cooperation from the DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office and other DoE staff. Agency staff and researchers deployed by the committee engaged in numerous discussions, and DoE provided data, papers, and presentations.

In summary, within the limitations described, the study utilizes a complement of tools to ensure that a wide spectrum of perspectives and expertise is reflected in the findings and recommendations. Appendix A provides an overview of the methodological approaches, data sources, and survey tools used in this study.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

Analyses and findings are organized as follows. Chapter 2 provides a review of program operations, describing the program in some detail and addressing a range of issues related to program management. Chapter 3 describes and analyzes agency initiatives that have been developed and implemented over the past 8 to 10 years. Chapter 4 reviews DoE data concerning applications and awards to the program, drawing out demographic and geographic differences as well as previous experience with the program. Chapter 5 provides a quantitative assessment of the program, drawing primarily on the National Academies’ 2014 Survey in the absence of data from DoE. Chapter 6 addresses the congressional mandate to foster the participation of women and minorities, drawing on data and other material from DoE and from the 2014 Survey. Chapter 7 draws on company case studies and on the textual responses from survey respondents to provide a qualitative picture of program operations, issues, and possible solutions. Chapter 8 provides the findings and recommendations from the study.

___________________

65 National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Workshop on Economics of Entrepreneurship, Washington, DC, June 29, 2015.

The report’s appendixes provide additional information. Appendix A sets out an overview of the methodological approaches, data sources, and survey tools used in this assessment. Appendix B describes key changes to the SBIR program from the 2011 reauthorization. Appendix C reproduces the 2014 Survey instrument. Appendix D lists research institutions identified by survey respondents as participating in DoE SBIR/STTR awards. Appendix E presents the case studies of selected firms with DoE awards. Appendix F serves as an annex to Chapter 5. Appendix G provides a glossary of acronyms used, and Appendix H provides a list of references.