2

Program Management

This chapter reviews key features of the DoE SBIR/STTR programs1 and highlights issues and concerns about their management. It introduces program initiatives launched by DoE, though these efforts are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3. The analysis found in this chapter is based on discussions with DoE staff, information from the 2014 Survey2 and from company case studies, and documentation provided by DoE.

The DoE SBIR/STTR programs serve the Office of Science (SC) divisions and Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) and other applied energy programs. This includes the Office of Science research programs—Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR), Basic Energy Sciences (BES), Biological and Environmental Research (BER), Fusion Energy Sciences (FES), High Energy Physics (HEP), and Nuclear Physics (NP), (collectively, the “science divisions”). The DoE SBIR/STTR programs also serve DoE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE), Office of Fossil Energy (FE), Office of Nuclear Energy (NE), and Office of Electricity Delivery and Energy Reliability (collectively, the “applied programs”), as well as the Office of Defense Nuclear Proliferation (DNP) and the Office of Environmental Management (EM). For fiscal year (FY) 2015, Congress allocated a total of approximately $6.6 billion to the SC divisions and EERE. Of this, less than $2 billion, or 29 percent, went to EERE. Within the Office of Science, BES received 26 percent, and HEP 12 percent (see Table 2-1).

___________________

1 The SBIR and STTR programs are operated in as unified manner as possible at DoE, and in this chapter the discussion covers both SBIR and STTR, designated collectively as “SBIR/STTR” unless specifically described otherwise.

2 As noted in greater detail at the beginning of Chapter 5, the overall target population for the survey reported in this chapter is DoE SBIR and STTR Phase II awards made during the period FY20012010, and most response data are reported at the project level. See Box 5-1 and Appendix A for a description of filters applied to the starting population. Averaged survey response data are reported to the nearest whole number.

TABLE 2-1 Total Funding Allocations for the Office of Science (SC) Divisions and the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE), FY 2015

| Office of Science (SC) Division | Amount of Funding (Millions of Dollars) | Percentage of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR) | 541 | 8.2 |

| Basic Energy Sciences (BES) | 1,733 | 26.2 |

| Biological and Environmental Research (BER) | 592 | 8.9 |

| Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) | 468 | 7.1 |

| High Energy Physics (HEP) | 766 | 11.6 |

| Nuclear Physics (NP) | 595 | 9.0 |

| Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) | 1,924 | 29.1 |

| Total: SC + EERE | 6,619 |

SOURCE: Congressional Research Service and the Department of Energy.

Each SC division and each applied programs of EERE and the other offices listed previously is invited to suggest topics and subtopics, and SBIR/STTR funding for each is largely aligned with its extramural funding. In essence, the set-asides for SBIR and STTR are applied to the extramural budgets of each participating science division and applied program, and the resulting funding amounts are approximately equal to the amount of funding available for SBIR/STTR topics related to their interests.

DOE SBIR/STTR STAFFING

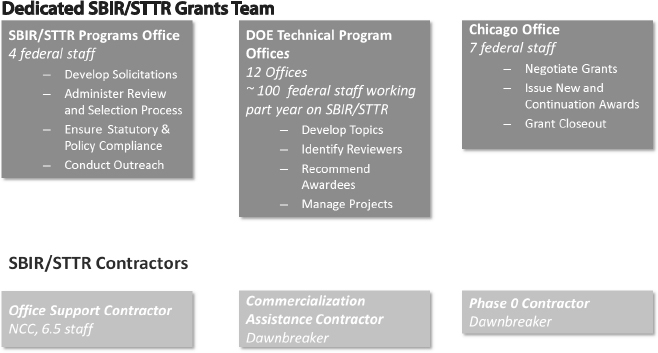

The DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office employs five full-time staff (one more in FY 2016 than in FY 2015), which represents a small portion of the workforce assigned to the program throughout DoE. The Program Office publishes solicitations, ensures compliance with program timelines and legislative requirements, and conducts outreach. Figure 2-1 shows the various components of the DoE SBIR/STTR programs as of FY 2015, including the DoE SBIR/STTR grants team depicted in the upper row of boxes, and the SBIR/STTR program contractors depicted in the lower row of boxes.

Approximately 100 federal staff in the program offices of the participating science divisions and applied programs manage the program’s technical aspects. These include technical points of contact (TPOCs) prior to the Phase I award and after an award is made. Also included are technical topic managers (TTMs) who develop topics and subtopics (which are approved by the SBIR/STTR Program Office), identify reviewers, discuss possible proposals with applicants, and recommend projects for an award, as well as Technical Project Managers (TPMs). As indicated, DoE uses a variety of titles for its technical topic and program managers and points of contact. The titles may be overlapping and a single person may serve one or all of these functions. For

SOURCE: DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office.

simplicity, we will refer to those functionally filling such positions as Topic Managers (TMs).

In recent years, the contracts support operation has changed. To improve the speed of throughput and to reduce difficulties caused by contract officers who are not familiar with the intricacies of SBIR and STTR awards, the contracts office has assigned seven full-time staff to the program. According to the Program Office, this change has significantly reduced the amount of time needed to finalize and process contracts.

Listed in Figure 2-1 in the contractor boxes is “Dawnbreaker,” a private contractor that provides two types of support services to the DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office: Advice to firms seeking to apply to the DoE program, i.e., “Phase 0 support,” and support services are to assist Phase I recipients plan for Phase II, and to provide commercialization assistance to Phase II awardees.

OUTREACH AND APPLICATION SUPPORT

DoE recognizes that it can derive significant agency-wide value from outreach activities to attract promising companies and technologies to the program. To this end, DoE participates in bus tours sponsored by the Small Business Administration (SBA) and in professional conferences and the national SBIR conference. However, it considers electronic communication to be the preferred approach to generate applications from companies that have not previously applied to the SBIR and STTR programs.

Digital Outreach

During the past few years, DoE has developed an extensive outreach program organized primarily around the digital delivery of information, notably through a library of webinars and an enhanced SBIR/STTR website and has emphasized efforts to drive traffic to these resources. The DoE SBIR/STTR website provides considerable material to help potential applicants understand eligibility criteria, nuances of the program, and the process for application. New potential applicants are strongly encouraged to review the 1.5-hour Overview Webinar, which covers all the basic information needed to apply for an SBIR or STTR award. The PowerPoint presentation underpinning the webinar is available separately. Beginning in March 2013, DoE also began to host technical webinars that focus on specific technology areas; in April 2013, it launched a webinar series on funding opportunities, focusing on application-related questions; and in 2015, it launched a webinar series that focuses on the technical aspects of application budgeting, beginning with indirect rates.

In acknowledgment of the increasing complexity of the application process, the homepage of the DoE SBIR/STTR website provides quick links to other online systems with which applicants must register: DoE’s Portfolio Analysis and Management System (PAMS), grants.gov, The U.S. government’s System for Award Management (SAM), SBIR.gov, and Dunn and Bradstreet (D&B). As with other agencies, a potential applicant can no longer apply to DoE before forming a company; however, in most U.S. states, a company can now be formed rapidly and at low cost online.

New Program Entrants

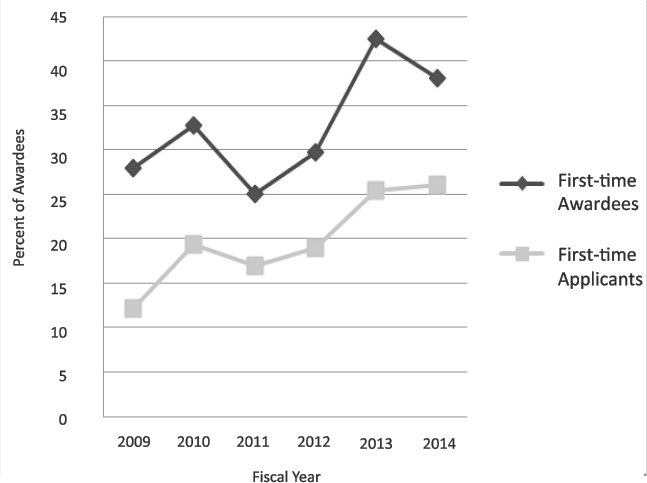

To maintain a robust program that serves a broad base of small businesses, it is considered important to ensure that the SBIR/STTR program attracts new applicants and that a substantial share of funding goes to companies without previous awards. Data provided by DoE and shown in Figure 2-2 indicate that new applicants constitute a growing percentage of the applicant pool—doubling from FY 2009 to FY 2014. The share of Phase I awards to companies that had not previously won a DoE SBIR/STTR award also increased significantly during this time period, to about 40 percent in FY 2013-2014. Therefore, there is evidence that DoE’s recent efforts to better inform potential applicants about the application process have been successful.

SOLICITATION TOPICS

Topic development at the DoE SBIR program3 is highly decentralized: individual topic managers in the science divisions and in the applied programs

___________________

3 The process has changed little in recent years. See National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the Department of Energy, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2008, pp. 94-95.

SOURCE: DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office.

have their own procedures for developing a list of topics for an upcoming solicitation, and the SC divisions have their own mechanisms for prioritizing amongst topics.

Each science division participates in one solicitation annually, separated into two releases to ease the workload in assessing applications and negotiating contracts. For the first of the two FY 2016 releases, science divisions ASCR, BER, BES, and NP participated, generating a total of 25 topics. The other science divisions and applied programs will participate in Release 2.

Narrow Topics

Each topic usually includes two to six subtopics, many of which are highly specific. For example, the FY 2016 solicitation included a call for “single bounce monolithic axis symmetric x-ray mirror optics with parabolic surface profile.”4 This degree of specification has been criticized by some company executives as potentially excluding other important technologies that may be a

___________________

4 DoE FY2016 SBIR/STTR Solicitation Release 1, Topic 5.

better fit for company expertise and easier to commercialize but that do not quite fit the specification.

Balancing Technical vs. Commercial Potential

Discussions with both program participants and company executives about the topic development process reinforced concern about a lack of commercial potential for some topics, especially those sponsored by the science divisions. Agency interviews indicated that most subtopics within the science divisions are generated by academic scientists at the National Laboratories. The SBIR/STTR Program Office performs some screening for commercial potential, but the effectiveness of this process is unclear. In addition, a number of company representatives interviewed for this study observed that DoE topics were often not focused on commercially valuable technologies—a point that is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5. On the other hand, topics can also emerge from consultations with small business concerns (SBCs). DoE’s SBIR/STTR Program Executive, Dr. Manuel Oliver, described a case in which an SBC initiated a subtopic that was accepted but did not win the resulting competition.

Structural Issues

The tension between aligning topics with the scientific interests of DoE scientists and engineers versus aligning topic selection for commercial potential partly reflects the source of funds within the SBIR/STTR program. Each division’s contribution of SBIR/STTR funding is proportionate to its share of extra-mural research funding: HEP, for example, oversees the allocation of approximately 11 percent of the SBIR/STTR funds because that is approximately equal to the percentage it receives of all DoE extra-mural research funds. HEP selects topics for SBIR/STTR projects to be funded out of approximately 11 percent of SBIR/STTR funds. This allocation of funding and influence over topic selection ignores systematic differences in commercial potential among the science divisions and the applied programs: commercial opportunities in high energy physics are not nearly as compelling as they are in renewable energy or fossil fuels because markets in high energy physics are smaller and needs are more specialized. For example, many research division topics support development of new scientific instruments, which, although valuable themselves, tend not to represent a large commercial market.

Dr. Oliver observed that in the past, funding was provided to the highest-scoring applications, regardless of division or program. However, this approach led to complaints from some staff in the science divisions, who believed that their reviewers were more critical and therefore scored applicants lower. The current system evolved in response to those complaints.

Open Subtopics

In part to address the criticism of overly constrained topics/subtopics, the science divisions and most of the applied programs now offer an “other” subtopic for most topics. Therefore, applicants to all the science divisions and some of the applied programs who have a technology that fits within the broad topic but is not within the more specialized subtopics are now able to apply. All of the topics published under the first FY 2016 release (in which ASCR, BES, BER, and NP participated) included an “other” subtopic, and SBIR/STTR Program Manager, Manny Oliver, said that initial tracking of “other” subtopics indicated that for the science divisions, “other” topics were drawing 7 to 9 percent of applications.

According to the DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office, only EERE does not now offer the opportunity of an “other” subtopic category. According to agency staff, EERE has gone one step further by deliberately narrowing its topics to ensure that the numbers of applications will decline to manageable levels. Discussions with program participants and company executives, referenced above, had indicated their concern about EERE’s use of overly specific topics because this practice threatened to limit their ability to apply, and, if they did apply, to limit their commercial potential.

Staffing Constraints

Reportedly EERE’s principal reason for not offering an “other” option is because of concerns that this would cause it to be overwhelmed with applications. Indicative that having an open subtopic might drastically increase the number of applicants was the fact recalled by Dr. Oliver that when EERE had previously published an “other” subtopic, more than 50 percent of all EERE applications were submitted in the “other” subtopic area. This response from companies also provides evidence supporting the view that the published topics are relatively narrow, and that potentially valuable technologies are likely being excluded from program funding.

The apparent imbalance between funding patterns and commercial opportunities leaves EERE in a conflicted position: EERE understands the important goal of commercialization to increase benefits from the SBIR/STTR programs. EERE participates in outreach activities to promote applications. At the same time, EERE believes it does not have the manpower to review a potential flood of applications or the dollars to fund many of the high-quality applications it would likely receive in response to having an open subtopic category

Substantial and sometimes rapid technological change is occurring across the energy sector: the options opened up by renewables, fracking, nuclear energy, and efforts to develop cleaner fossil fuels have driven significant commercial investments. However, DoE and its SBIR/STTR programs remain structured around more traditional views of the energy sector. The narrowness

of the opening for applications is clear. For example, in the FY 2016 funding round, EERE offered two subtopics within solar energy:

- Controls and systems for on-site consumption of solar energy. Within this subtopic, a number of areas of interest are identified: Areas of interest include, but are not limited to: (1) automated and predictive analytics applied to building load controls; (2) automated design tools for the development of integrated PV generation, load controls, electric vehicles and/or stationary storage, (3) intelligent controls for the charging and discharging of storage systems; (4) techniques and methods for incorporating short-term weather projections; (5) rapid, efficient, and safe installation of behind-the-meter storage, controls, and generation; and (6) techniques and methods for monetizing integrated PV, load response, and storage in electricity markets.

- Shared Solar Energy Development Tools. Areas of interest include, but are not limited to: (1) development of new platforms that reduce the cost of customer acquisition for shared solar hosts and participants; and (2) data collection, billing, and project management automation.5

Notably, both subtopics are open to applications within the defined technical area that is not listed as one of the “areas of interest.” However, potential applications in areas outside the two defined subtopics are not eligible for funding.

Topics from Science vs. Applied Divisions

Topics within the science divisions in large measure remain unchanged from year to year, and in some cases subtopics remain unchanged or similar as well. Comparing the topics and subtopics in FY 2015 and FY 2016 (for Release 2), there were 6 new topics out of 32 (mostly in topics managed by the office of defense nuclear nonproliferation), while there were 52 new subtopics out of 186 total (30 percent). Fusion Energy and Nuclear Energy were the offices with the highest percentage of identical subtopics. However, in some areas, there was 100 percent change between years.

In the applied programs, however, subtopics do change annually. In FY 2015, for example, in EERE there were five solar energy subtopics:

- Analytical and Numerical Modeling and Data Aggregation

- Concentrating Solar Power: Novel Solar Collectors

- Concentrating Solar Thermal Desalination

- Grid Performance and Reliability

- Labor Efficiencies through Hardware Innovation6

___________________

5 DoE SBIR/STTR Topics FY2016 Phase I Release 2, November 23, 2015, pp. 50-51.

6 DoE SBIR/STTR Topics FY2015 Phase I Release 2, November 23, 2014, p. 59.

In contrast, in EERE in FY 2016 there were only the two subtopics noted previously, both of which were entirely different from the 2015 subtopics.

- Controls and Systems for the On-Site Consumption of Solar

- Shared Solar Energy Development Tools7

In both cases, the solar topics reflect technical needs identified in the context of a large DoE/EERE solar initiative—the SunShot Initiative.8 Yet, while DoE solar topics for at least 2015 and 2016 have been based on needs identified by the SunShot initiative, the subtopics changed and became more restrictive.

Overall, although the need to tailor the number of applications to the resources available is understandable, the approach adopted by EERE and more broadly by DoE in the distribution of funds means that potentially significant technologies are excluded from the SBIR/STTR programs before their value can be assessed.

THE APPLICATION PROCESS

Eligibility

The SBIR/STTR programs are in practice no longer open to individual applicants who do not have a registered company. Applicants must register with a number of government or government-mandated databases before they can apply for funding. They must have an Employer Identification Number (EIN) from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), register on the primary government grants website (grants.gov) and the System for Award Management (SAM), have a DUNS number from Dunn and Bradstreet, and finally register with DoE’s electronic management grants system (Portfolio Analysis and Management System, or PAMS). The reality, therefore, is that applicants must complete a considerable amount of paperwork and display a certain degree of commitment before they can apply for funding, as is true for all the major SBIR-awarding agencies.

Timeline

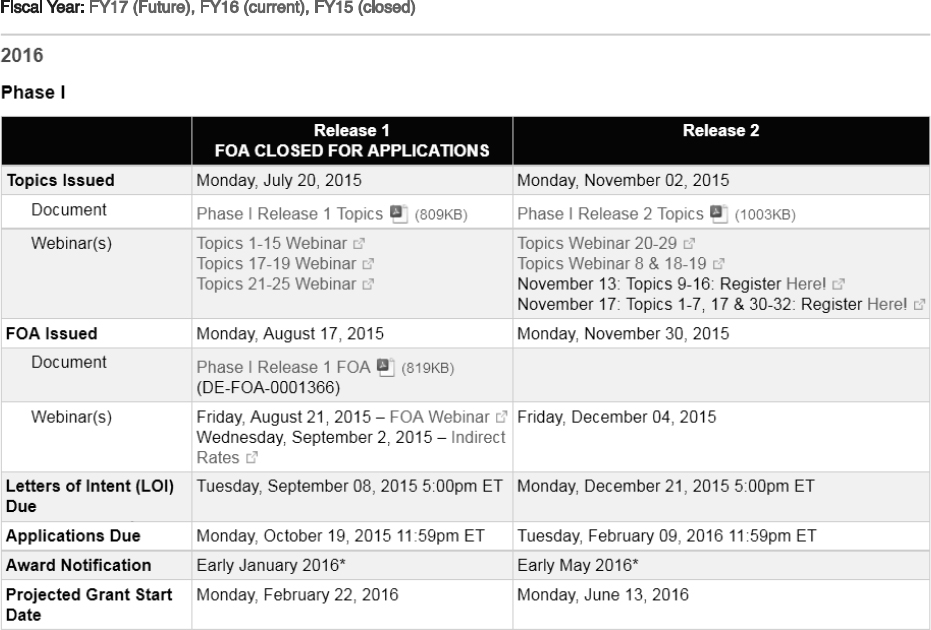

The DoE application process follows a tight and transparent timeline that is readily available to applicants (see Figure 2-3). According to DoE, the

___________________

7 DoE SBIR/STTR Phase I release 2 topics, November 2015, p.51. http://science.energy.gov/~/media/sbir/pdf/TechnicalTopics/FY2016_Phase_1_Release_2_Topics_Combined.pdf.

8 The SunShot Initiative works in partnership with industry, academia, national laboratories, and other stakeholders to achieve subsidy-free, cost-competitive solar power by 2020. The potential pathways, barriers, and implications of achieving the SunShot Initiative price-reduction targets and resulting market penetration levels are examined in the SunShot Vision Study. (http://www1.eere.energy.gov/solar/sunshot/vision_study.html).

deadlines are posted on the DoE SBIR/STTR website 1 year in advance so that potential applicants have time to fully prepare (see Figure 2-4).

Applicants have approximately 1 month between the date that the topics are released and the date that the Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) is released. This period provides potential applicants with an opportunity to connect with subtopic managers to discuss technical elements of a proposed project and to become familiar with the somewhat complex application process now required by all federal SBIR agencies.

DoE has made efforts in recent years to compress the timeline and, at the same time, to allot companies more time to develop higher quality proposals. DoE claims to be now making decisions within 90 days of the application deadline.9

Unpublished data provided to the committee from an interagency working group that recently reviewed award timelines at all the SBIR/STTR agencies revealed that DoE has significantly improved its Phase I award selection time (defined as the lag between Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) and award announcement), down from about 160 days in FY 2011 to below the 90-day benchmark mandated by SBA in FY 2013. DoE almost met the 90-day benchmark for Phase II selection by 2011 and continued to make improvements in 2012 and 2013.10

Letters of Intent

After the FOA is released, applicants have about 3 weeks to develop a letter of intent (LOI) (see Box 2-1). DoE limits the number of LOIs to 10 per company per solicitation, which therefore also limits the total number of applications from a single company. According to DoE, the intended purpose of LOIs is to assign appropriate technical reviewers; not to weed out weak proposals. The distribution of LOIs will signal the likely pattern of Phase I applications downstream.

DoE responds to LOIs, but only to indicate whether the proposed project is responsive to the topic. Although projects deemed nonresponsive can still apply, this step in the process may cause some potential applicants to decide to not apply. Thus, the limitation on LOIs to 10 and the DoE response to LOIs that may indicate that they are not considered responsive to topic, in effect, may reduce the number of applications from what they otherwise would have been. This may sharpen companies’ focus on identifying what they want to submit, and reduce the burden on the DoE reviewer process. The final Phase I application is due 5 weeks after the LOI is due and must be submitted electronically.

___________________

9 Manny Oliver, “DoE’s SBIR and STTR Programs,” DoE Webinar, December 4, 2015, p. 45.

10 See Chapter 3, “Program Initiatives,” for a more detailed analysis.

SOURCE: DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office.

SOURCE: DoE website. Accessed November 11, 2015.

The Program Office provided quantitative details about the effect of the LOI process on application patterns (see Figure 2-5). Of the 2,852 LOIs received in FY 2014, 572 (21 percent) were deemed unresponsive to the topic. Of these, 97 (17 percent) applied for funding anyway, and, of these, 8 percent received an award (about one-half the rate of the applicants with responsive LOIs). Thirty percent of applicants with responsive LOIs did not apply, so the actual impact of the LOI process can be estimated: assuming that all applicants submitting an LOI were equally likely to apply, a negative response led to a substantial reduction in the proportion of LOIs from that group resulting in applications. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that a negative response to the LOI has a significant impact on the decision to apply.

Technical and Commercialization Plans

DoE provides an Instruction Guide for would-be applicants to use in preparing an SBIR/STTR Phase I grant application.11 For preparing Fast-Track and Phase II guidance, DoE refers applicants to the respective Funding Opportunity Announcement.

___________________

11 DoE, Instructions for Completing a DOE SBIR/STTR Phase I Grant Application. See http://science.energy.gov/~/media/sbir/pdf/Application_Resources/Application_Guide.pdf.

In addition to the various forms and data entries, a Phase I application contains a project narrative describing the problem or situation that is being addressed and how it will be addressed, including the proposed technology and related research design, research objectives, and methods and technical approach to be used. The applicant is asked to provide enough background information that the importance of the problem/opportunity is clear, and to provide enough information on the technical approach to make it clear how the proposed research will address the problem or take advantage of the opportunity.

Project Narrative

The project narrative also describes commercial potential of the proposed project, in terms of expected future applications and/or public benefits if the project is continued into Phase II and beyond. The applicant is asked to discuss the technical, economic, social, and other benefits to the public as a whole that are anticipated if the project is successful and is carried forward. The applicant is asked to describe the resultant product or process, the likelihood that it could lead to a marketable product, the significance of the market, and the identity of specific groups in the commercial and public sectors that would likely benefit from projected results.

Revenue Forecast

While acknowledging that Phase I commercialization plans will vary greatly with technology and application—such as for delivering improved technologies into existing markets versus delivering new technologies into emerging markets, DoE requires a revenue forecast over a 10-year period mandatory for Phase I applications.12 This requirement is aimed at ensuring that companies do not find their proposed market to be too small for commercial operations after completion of Phase II. This is an interesting effort by DoE to balance the need to ensure that companies are working on technologies with potential commercial viability with the obvious difficulties of forecasting revenues for products that in some cases will not enter markets for many years.

Commercialization Plan

Phase II, including Phase IIB, applications require more substantial commercialization plans. Review of Phase IIB applications (discussed in Chapter 3) is more closely focused on commercial potential: 50 percent of the numerical weighting is assigned to impact, and two reviewers evaluate the commercialization plan.

___________________

12 DoE provided a detailed Phase I commercialization plan as an example. See http://science.energy.gov/~/media/sbir/pdf/docs/ExamplePhaseICommercializationPlan61112.pdf.

The Review Process

The review process begins with an administrative review by the SBIR/STTR Program Office to ensure that the application includes all the relevant materials. After passing this initial screening, the application is forwarded to the TM who initiated the relevant subtopic.

There are four criteria for award selection:

(1) the significance of the technical and/or economic benefits of the proposed work, if successful, (2) the likelihood that the proposed work could lead to a marketable product or process, (3) the likelihood that the project could attract further development funding after the SBIR or STTR project ends and (4) the appropriateness of the data management plan for the proposed work.

Selection Criteria

Commercial potential is considered under criterion number two. Although, as described above, some commercialization information is required for Phase I, a full-scale commercialization plan is required for Phase II. Four selection criteria apply to commercialization potential: (1) Market Opportunity, (2) Company/Team, (3) Competition/Intellectual Property, (4) Finance and Revenue Model. For many years, technology transfer staff at the National Laboratories reviewed these plans, but the Program Office determined that this work was not an appropriate use of their time and contracted with a commercial third-party to conduct the commercialization plan reviews.

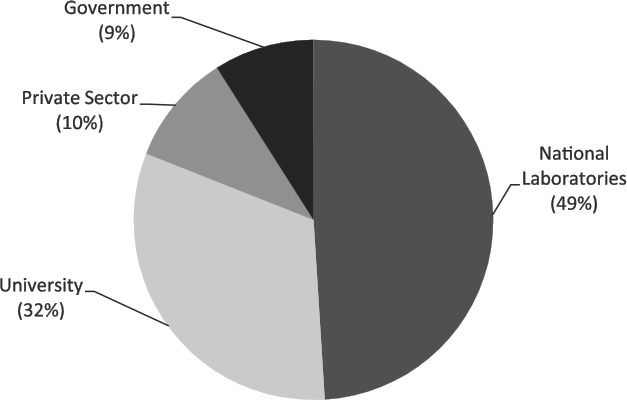

Three reviewers are assigned to each Phase I and each Phase II application. Dr. Oliver said that about 50 percent of the reviewers are from National Laboratories, 30 percent are from universities, and 20 percent are from the private sector or other federal agencies (see Figure 2-5).

The Scoring System

Each reviewer generates a separate score for each of the four scoring criteria. Unlike NIH, there is no opportunity to discuss scores or develop a consensus. For each category, the proposal is rated as not acceptable, acceptable, or outstanding—and these are translated into a numerical scoring system with a very limited set of numbers corresponding to each descriptive rating. The numerical scores are averaged to generate an aggregate score for the proposal, which is reviewed by the TM who provides an independent score. If the TM score differs from the reviewers’ average score, then the TM must provide a written justification for the difference in any of the three scoring categories. This justification is especially important when the TM is recommending the project for funding, according to Dr. Oliver.

SOURCE: Manny Oliver, “DoE’s SBIR and STTR Programs,” DoE Webinar, December 4, 2015, p. 46.

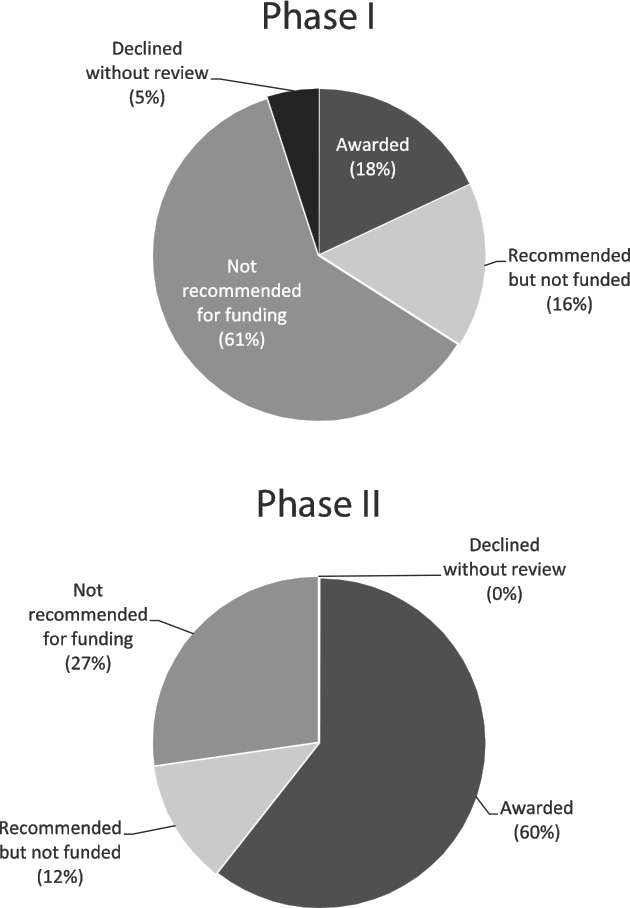

The limited scoring system significantly impacts the process and applicants’ perception of the process. First, projects that do not receive an outstanding score in all three categories cannot easily recover. A maximum score for impact is unlikely to outweigh a less than favorable capabilities score. Second, there may be a lack of distinction among numerical scores of projects scored as outstanding (see Figure 2-6), while at the same time there is not enough funding to support all of the projects scored as outstanding. Almost as many Phase I applications are recommended but not funded (16 percent) as are recommended and funded (18 percent). Twelve percent of Phase II awards are recommended but not funded. From the applicant’s perspective, learning that they received a score of “outstanding” and did not receive funding, while others with the same score did receive funding would likely be perceived as a lack of transparency and possible unfairness. A clear statement of selection criteria, a more nuanced scoring system that indicates ranking among proposals, and announcement of where the funding cut-off occurred, such as some aspects of the selection process used at NIH, helps prevent perceptions that the selection process lacks transparency and fairness.13

___________________

13 For an overview of the selection process at the National Institutes of Health, see National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, SBIR/STTR at the National Institutes of Health, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2015, pp. 41-50.

SOURCE: Manny Oliver, “DoE’s SBIR and STTR Programs,” DoE Webinar, December 4, 2015.

Internal Ranking

At the conclusion of the initial review process, the TM initiates an internal ranking process for applications, first for the subtopic and then—in conjunction with other subtopic managers—for the topic overall. TM rankings are then aggregated across a program area and reviewed by senior management (often an Assistant Secretary, although the precise staff assigned varies by division). At the end of the review, a final ranking is provided by each science division and applied program. The DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office then provides a funding cut-off for the program, which is applied to the final ranking. There is room for some adjustment, particularly in the case of small programs whose funding might be rounded up to the next whole award (e.g., up from funding 1.2 awards to funding 2 awards).

Since DoE’s deployment of the PAMS system in FY2013, DOE has made reviewer comments available online for all applicants.

AWARDS MANAGEMENT

DoE has moved from the paper-driven process described in the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2008 report14 to a completely electronic application and awards management system, an adapted version of the system in use at NASA and provided by REI, a third-party contractor.

In addition, DoE has changed its organizational structure for managing applications and handling SBIR/STTR contracts. Previously, the Program Office utilized staff in the Chicago DoE contracting operation on an ad hoc basis to process applications and awards. In some cases, the staff were not familiar with SBIR/STTR,15 and the Program Office incurred additional training costs to ensure that the number of staff assigned part time to SBIR/STTR were sufficiently familiar with the program. In 2012, the Program Office arranged to have contracts staff in Chicago dedicated to the SBIR/STTR Programs. This arrangement was made possible in part by the decision to release two annual solicitations, with some divisions participating in the spring and the others in the fall.

The resulting steadier workflow has allowed for dedicated staff, and the arrangement appears to be working well: overall, interviewees and 2014 Survey respondents had a strongly favorable view of awards management at DoE. They observed that deadlines were clear and generally met and that payment procedures were rapid and effective.

___________________

14 National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the Department of Energy.

15 See Appendix E for some cases in which this caused considerable difficulties.

AWARDS TRACKING AND EVALUATION

DoE has tracked program outcomes for a number of years through post-award surveys. These surveys were first deployed on paper and now via the web. The surveys have been deployed periodically (not annually), and the next planned survey has been delayed until all awards data are available for incorporation. The Program Office anticipates that it will be deployed shortly. Program managers will be able to use the internal DoE awards tracking database (PAMS) to view selection decisions and outcomes by company and by technology, and to follow progress and patterns of success at the division/program level.

Because outcomes data collected in PAMS were not made available to the committee due to issues of privacy, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of this approach and options for improving it. It is also difficult to determine how widely the existing data are utilized for program management. The Program Office clearly has plans for more extensive utilization and has hired one new staff member in this area.

COMMERCIALIZATION SUPPORT

DoE provides commercialization support for awardees through a $1.5 million annual contract with Dawnbreaker, a third-party service provider. Through a range of services, Dawnbreaker provides assistance to companies to write Phase I proposals, to Phase I companies to write Phase II proposals, and to Phase II companies to improve their commercialization plans. Commercialization support provided by DoE is described in detail in Chapter 3.

STTR

To the maximum extent possible the DoE STTR program is operated in parallel with the SBIR program, as indicated by the previous combined treatment. There is no separate solicitation; the topics are identical for both programs; application and award deadlines are identical; and companies can apply simultaneously to SBIR and STTR, leaving it to DoE staff to determine which program is more suitable. DoE has explicitly stated that it has no separate strategic objective for the STTR program and would prefer that the programs be combined if feasible. However, mandatory differences between the programs remain:

- STTR requires that the SBC enter into a formal partnership with a research institution (RI), which includes an agreement with respect to intellectual property (IP).

- STTR requires that at least 30 percent of the work be done by the RI and at least 40 percent by the SBC.

- STTR eliminates the SBIR requirement that the principal investigator (PI) on the project work at least 51 percent time for the SBC.

- DoE provides additional time for STTR Phase I (9 months instead of 6 months).16

DoE manages the STTR and SBIR programs as being administratively and functionally identical, which reduces administrative overhead. While aware of the congressionally-mandated differences between the programs, the agency does not see any significant or strategic distinctions between them. Small businesses in both programs collaborate with RIs, and only a small percentage of STTR awards go to PIs employed primarily by an RI.

DoE offers one Phase I STTR solicitation from each participating science division and applied program annually, split into two releases. Uniquely among the funding agencies, both Phase I and Phase II applicants can apply to either program or to both using a single application—as long as they meet the qualifications for both. Approximately as many applicants select both SBIR and STTR as select just one of them.

Annual funding for STTR is about $25 million. Awards are highly competitive, with a success rate of about 10 percent for STTR Phase I and 50 percent for STTR Phase II. DoE offers the same performance period and award size for both programs. Phase I awards last 9 months for either $150,000 or $225,000. Phase II awards last 24 months, and may be for $1 million or $1.5 million.

The DoE SBIR and STTR programs have recently increased their emphasis on the commercialization of funded technologies. Because the programs focus on providing seed capital for early-stage research and development (R&D) with commercial potential, SBIR/STTR Phase I and Phase II applications must provide an initial evaluation of commercial potential. Awards are, like those at other agencies, comparable in size to large early stage angel investment. However, both programs will deliberately accept greater risk than will angel investors, in support of the agency mission.

Although STTR is designed to encourage collaborations between small companies and RIs, many DoE SBIR projects exhibit collaborations as well. More than one-half of all Phase II SBIR projects include some funding for RIs, and overall about 9 percent of SBIR funding goes to RIs.17

The STTR program supports an extensive set of collaborations with DoE National Laboratories, which on average partner on about one-third of DoE’s STTR projects. According to the DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office, their share has varied—from a high of 80 percent in FY 1999 to a low of 13 percent in FY 2014, while averaging about a third.18

___________________

16 Manny Oliver, “The DoE STTR Program,” presentation at the NAS STTR Workshop, May 1, 2015; discussions with DoE staff; and other material provided by DoE.

17 Manny Oliver, private communication.

18 See Chapter 3 (Program Initiatives) for a further discussion of National Labs and STTR.

Principal investigators (PIs) for DoE projects mostly come from SBCs, with only 13 percent coming from RIs (including a small number primarily employed at National Laboratories)—even though STTR permits the PI to be primarily employed at the RI. In FY 2014, 3 out of 35 STTR PIs were employed at the RI.19

Like the other agencies, DoE has followed the 2011 reauthorization law to permit awardees to switch between SBIR and STTR when entering Phase II. DoE has found that some STTR Phase I awardees are switching from STTR to SBIR during Phase II, but not the reverse. Since the program permitted such a switch in FY 2011, 10 out of 83 STTR Phase I awardees applying for Phase II funding sought SBIR Phase II funding, and 4 received it. 20

SBIR/STTR PROCESS ISSUES

To build on the analysis provided in the National Academies 2008 report21 on the DoE SBIR program, the current assessment sought to identify additional information about the process of implementing SBIR/STTR awards, with a view to providing management with more detailed information about program operations. This section considers several operational aspects of the program.

Funding Gaps

In some cases, the flow of funding from DoE to the awardee can be interrupted between phases of an SBIR/STTR award. This problem is especially challenging for small firms, which are less likely than larger firms to have other funding sources to keep projects alive until Phase II funding arrives. In recent years, DoE has tried to address the problems of funding gaps. Sixty-five percent of SBIR and STTR respondents indicated that they had experienced a gap between the end of Phase I and the start of Phase II for the surveyed award.22 As shown in Table 2-2, this funding gap can have a range of consequences for the company. Fifty-nine percent of respondents reported that they stopped work altogether during this period, while 35 percent worked at a reduced level of effort. Five percent maintained or increased the pace of their work. Aside from the obvious direct impact of delayed projects, funding gaps can have long-term consequences, especially for smaller companies, where in some cases there is insufficient work to retain key project staff during the gap period.

DoE has largely addressed the funding gap by shortening the timeline between the end of Phase I and the beginning of Phase II. It has not utilized

___________________

19 Manny Oliver, private communication.

20 Ibid.

21 National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the Department of Energy.

22 2014 Survey, Question 22.

TABLE 2-2 DoE SBIR and STTR: Effects of Funding Gaps Between Phase I and Phase II, Reported by 2014 Survey Respondents

| Percentage of Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | SBIR Awardees | STTR Awardees | |

| Stopped work on this project during funding gap | 59 | 61 | 48 |

| Continued work at reduced pace during funding gap | 35 | 33 | 48 |

| Continued work at pace equal to or greater than Phase I pace during funding gap | 5 | 5 | 9 |

| Received gap funding between Phase I and Phase II | 1 | 1 | |

| Company ceased all operations during funding gap | 1 | 1 | |

| Other | 2 | 2 | |

| N = Number of Respondents Reporting a Gap Between Phase I and Phase II | 167 | 144 | 23 |

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 23.

some of the tools available for this purpose at other agencies; for example, NIH allows companies to work at their own risk, recouping costs expended on Phase II work during the gap if the Phase II is eventually awarded.

Ease of Application

The 2014 Survey also sought to probe more deeply into award recipient perspectives on application and award management. One question concerned the degree of difficulty involved in applying for a Phase II award compared with applications to other federal programs. As shown in Table 2-3, 31 percent of respondents reported that the application process was easier or much easier than for other sources of federal funding, and 15 percent of respondents indicated that it was more difficult or much more difficult.

Amount of Funding

Although there are obvious limitations to the utility of asking recipients whether the amount of money provided was sufficient for the surveyed project, there is at least some value in determining the extent of positive responses. It should also be noted that the funding amounts changed during the period covered by the survey. As shown in Table 2-4, in this case 66 percent of respondents said the amount was about right or more than enough, and 34 percent said that the amount was insufficient.

TABLE 2-3 Ease of Application for SBIR and STTR at DoE, Reported by 2014 Survey Respondents

| Percentage of Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | SBIR Awardees | STTR Awardees | |

| Much easier than applying for other federal awards | 14 | 14 | 10 |

| Easier | 17 | 18 | 13 |

| About the same | 44 | 44 | 40 |

| More difficult | 10 | 9 | 17 |

| Much more difficult | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| Not sure, not applicable, or not familiar with other Federal awards or funding | 11 | 10 | 17 |

| N (Number of Respondents) | 246 | 216 | 30 |

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 53.

TABLE 2-4 Adequacy of Phase II Funding, Reported by 2014 Survey Respondents

| Percentage of Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | SBIR Awardees | STTR Awardees | |

| More than enough | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| About the right amount | 65 | 65 | 63 |

| Not enough | 34 | 34 | 37 |

| N (Number of Respondents) | 248 | 218 | 30 |

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 54.

Size of Awards

Although awardees often suggest in other contexts (e.g., case study interviews) that the size of awards should be increased, especially before the recent changes were made during reauthorization, the 2014 Survey asked directly about the possible trade-off between the size of awards and the number of awards—the trade-off being that unless agency funding for SBIR or STTR programs increases, larger awards inevitably imply fewer awards. In the context of that trade-off, a majority of respondents did not believe that increases in award size would be appropriate (see Table 2-5).

Program Size

The survey also asked about the possible expansion of the SBIR/STTR programs. Perhaps not surprising, about two-thirds of respondents overall indicated that they would support an increase in program size, even if funding were taken from other federal programs that they value. (See Table 2-6.)

TABLE 2-5 Preference for Larger but Fewer Awards, Reported by 2014 Survey Respondents

| Percentage of Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | SBIR Awardees | STTR Awardees | |

| Yes | 21 | 23 | 10 |

| No | 57 | 56 | 57 |

| Not sure | 23 | 21 | 33 |

| N (Number of Respondents) | 248 | 218 | 30 |

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 55.

TABLE 2-6 Views on changing the Size of the SBIR/STTR Program, Reported by 2014 Survey Respondents

| Percentage of Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | SBIR Awardees | STTR Awardees | |

| Expanded (with equivalent funding taken from other federal research programs you benefit from and value) | 67 | 67 | 70 |

| Kept at about the current level | 32 | 32 | 30 |

| Reduced (with equivalent funding applied to other federal research programs you benefit from and value) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Eliminated (with equivalent funding applied to other federal research programs you benefit from and value) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| N (Number of Respondents) | 246 | 216 | 30 |

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 56.

Working with Topic Managers

Interviews with Project Managers have suggested that a critical factor affecting the success of SBIR and STTR projects may be the relationship between the awardee and the DoE Topic Manager (TM).23 The 2014 Survey of award winners asked a series of questions aimed at identifying ways in which this relationship might be improved.

Engagement with TMs

Respondents were asked to indicate how often they engaged with their TM. Thirty-nine percent reported annual contact, and 44 percent reported quarterly contact (see Table 2-7).

___________________

23 As was explained earlier in this chapter, DoE uses a variety of titles for the technical manager of a topic or subtopic. In this report, we refer to all those functionally filling this position as Topic Managers (TMs).

TABLE 2-7 Frequency of SBIR and STTR Contact with DoE TMs, Reported by 2014 Survey Respondents

| Percentage of Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | SBIR Awardees | STTR Awardees | |

| Weekly | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Monthly | 15 | 16 | 10 |

| Quarterly | 44 | 45 | 40 |

| Annually | 39 | 37 | 50 |

| N (Number of Respondents) | 239 | 209 | 30 |

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 59.

Another survey question asked about the ease or difficulty that respondents had in contacting their DoE TMs, and another asked if the TM had sufficient time to spend on their project. In response, 88 percent of respondents reported that it was easy or very easy to contact the TM when necessary,24 and only 7 percent reported that the TM had insufficient time to spend on their project.25

At some agencies, the rotation of program managers has been a problem for awardee companies, especially where the program manager has a function in connecting the company to Phase III opportunities within the agency. In general, however, TM rotation has not seemed a serious problem at DoE; only 17 percent of respondents indicated that their TM was replaced during the Phase II award.26

Value of the TM to the Company

Interviews indicated that some TMs have had very positive effects on their awardee companies, while others have been of little help. The survey attempted to gauge the distribution of utility by asking respondents how helpful the TM was to their project (see Table 2-8). Overall, 40 percent of respondents scored TM usefulness at 4 or 5 on a 5-point scale, with 5 being invaluable. Conversely, 29 percent scored usefulness at 1 or 2.

TM Technical Understanding of SBIR/STTR

One important role of the TM is to provide technical advice to the awardee about the operations of the SBIR/STTR. It is fairly complex, so a technically knowledgeable TM can be of great use, especially to companies that are new to the program. The survey therefore asked respondents about their views on the TM’s technical capacity with regard to SBIR/STTR. Overall,

___________________

24 2014 Survey, Question 65.

25 2014 Survey, Question 67.

26 2014 Survey, Question 66.

TABLE 2-8 Usefulness of the TM, Reported by 2014 Survey Respondents

| Percentage of Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | SBIR Awardees | STTR Awardees | |

| Invaluable (5) | 15 | 16 | 10 |

| 4 | 26 | 26 | 23 |

| 3 | 30 | 31 | 30 |

| 2 | 16 | 17 | 13 |

| No help (1) | 13 | 11 | 23 |

| N (Number of Respondents) | 240 | 210 | 30 |

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 60.

respondents appeared satisfied; almost three-quarters indicated that their TM was extremely knowledgeable or quite knowledgeable about SBIR/STTR. Only 6 percent of respondents indicated that the TM was not at all knowledgeable, while 74 percent said that the TM was extremely or quite knowledgeable.27

At some agencies, TMs or the equivalent provide support also for Phase II proposals. At DoE, this function is primarily outsourced to Dawnbreaker, so it is not surprising that only about a one-quarter of survey respondents indicated that the TM was very or somewhat helpful regarding Phase II proposals and awards.28

Because TMs are usually technically knowledgeable about the science and engineering involved in the award, they can sometimes provide valuable direct insights. Twenty percent of respondents indicated that they received substantial technical help from the TM, while 58 percent indicated that they received little or none.29 TMs may also be in a position to introduce awardees to technical staff at research institutions (including National Laboratories) who may be able to provide critical technical support. About one-quarter of respondents indicated that this was the case for their project.30

BEYOND PHASE II

Commercialization initiatives, discussed in detail in Chapter 3, seek to provide additional support for companies as they seek to commercialize beyond the SBIR program’s second phase. However, despite the new initiatives, the support that DoE offers beyond Phase II is limited. In particular, no programs are in place to link SBIR/STTR projects to potential uses inside DoE at the National Laboratories. A number of company executives interviewed for this report described their difficulties in persuading DoE programs to adopt

___________________

27 2014 Survey, Question 61.

28 2014 Survey, Question 62.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

technologies that they had apparently sponsored through SBIR. For example, the technologies developed by Vista Clara were in part designed to help with the cleanup of contaminated groundwater, an important priority for DoE. Yet, there is no program in place to connect the company and its technology to DoE groundwater programs. In fact, the company’s strong connections to the nuclear cleanup of the Hanford Site in southeastern Washington State, overseen by two DoE Offices, have resulted in no sales, because the cleanup there is led by a third-party contractor (analogous to a Department of Defense prime) with no obligations or connections to the SBIR/STTR program.31

The DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office has been run on a very lean basis.32 As a result, the office has limited its focus to the operation of the program itself, now with additional emphasis on outreach and support during Phase I and Phase II. These priorities are understandable and appropriate. However, other agencies have developed initiatives that link SBIR/STTR technologies to market opportunities in the sectors relevant to the agency, and there is no reason why DoE could not profitably follow their example. Navy operates the Navy Opportunity Forum, Air Force hosts a series of transition meetings between large companies and SBCs, and NASA maintains online access to SBIR/STTR technologies.

Technology Transfer Opportunities

In 2013, DoE began a new technology transfer initiative, using the SBIR and STTR programs to transition technology developed at DoE National Laboratories and universities to the marketplace. To accomplish this, DoE began setting aside a number of awards for Technology Transfer Opportunities (TTOs), which are subtopics for which National Laboratories offer technologies that could be appropriate for transition into a SBIR- or STTR-related project.33 Because the agency is prohibited by statute34 from using only the STTR program to foster technology transfer from its laboratories, it uses both SBIR and STTR, and doing so creates a range of new opportunities for collaboration between companies and RIs. The number of TTO subtopics and awards are listed in Table 2-9. Subtopics are written to describe the state of the existing technology at the lab and to underscore the point that the opportunity here is to find a commercial partner. This is, in contrast to standard topics where the opportunity is to develop a new technology to address a defined problem.

___________________

31 See Appendix E (Case Studies).

32 See National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the Department of Energy.

33 Subtopics for Technology Transfer Opportunities are published in the standard SBIR/STTR solicitation.

34 See Commerce and Trade Law 2015 (Annotated): USC Title 15. See also “The STTR Program at the Department of Energy,” Presentation by Manny Oliver, Director, DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office, National Academies Workshop on the STTR Program, Washington, DC, May 1, 2015.

TABLE 2-9 Adoption of Technology Transfer Opportunities (TTOs) at DoE, FY2013-15

| TTO subtopics | FY I Awards | FY II Awards | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FY 2013 | 18 | 2 | 0 |

| FY 2014 | 33 | 8 | 1 |

| FY 2015 | 31 | 8 | 3 |

SOURCE: DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office.

SBIR/STTR and the National Laboratories

At DoE, many STTR awards in particular involve partnerships with DoE National Laboratories. This is not the case for other agencies, although all have at least some STTR awards for which a National Laboratories is the Research Institution partner. Much of the discussion in this section focuses on STTR linkages between SBC's and National Laboratories. As shown in Table 2-10, DoE’s 17 National Laboratories are sponsored by six different programs within DoE. Partnerships with the National Laboratories account for a substantial percentage of all the STTR partnerships between SBCs and RIs at DoE. Partnerships with National Laboratories account for about one-third of all Phase I and Phase II RI partnerships (see Table 2-11).

Partnerships with National Laboratories account for 28 percent of STTR Phase I research partnerships and 33 percent of Phase II partnerships. DoE should consider exploring whether partnering with a National Lab is associated with a higher success rate for applications, given the potential for conflicts of interest. The fact that the most applied of the laboratories—National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL)—account for a relatively low percentage of partnerships, suggests that partnering with the laboratories may be driven more to access very specialized technologies (such as accelerators) and related markets than it is to more generalized technologies.

Although disputed by DoE, some of the conclusions about management of the national laboratories are also reflected in comments from interviewees for this study and from survey respondents. A number of reports have highlighted what are perceived as growing issues in DoE management of the laboratories, that is, multilayered management with inflexible rules. The National Academy of Public Administration, for example, concluded in 2013 that DoE management of lab operations “...not only define the deliverables and due dates [of lab work and research] but are very prescriptive about the interim steps to be followed to complete the work assignment.”35 Also in 2013, a joint bipartisan study by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, Center for American Progress, and Heritage Foundation found that “DoE has replaced contractor

___________________

35 National Academy of Public Administration, “Positioning DoE’s Labs for the Future,” Washington, DC: NAPA, January 2013, p. 23.

TABLE 2-10 Location and Sponsoring Program for DoE National Laboratories, FY 2015

| DoE Sponsoring Agency | DoE Lab | Location |

|---|---|---|

| National Nuclear Security Administration | Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory | Livermore, California |

| Los Alamos National Laboratory | Los Alamos, New Mexico | |

| Sandia National Laboratory | Albuquerque, New Mexico | |

| Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy | National Renewable Energy Laboratory | Golden, Colorado |

| Office of Environmental Management | Savannah River National Laboratory | Aiken, South Carolina |

| Office of Fossil Energy | National Energy Technology Laboratory | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Morgantown, West Virginia |

| Office of Nuclear Energy | Idaho National Laboratory | Idaho Falls, Idaho |

| Office of Science | Ames Laboratory | Ames, Iowa |

| Argonne National Laboratory | Argonne, Illinois | |

| Brookhaven National Laboratory | Upton, New York | |

| Fermi National Laboratory | Batavia, Illinois | |

| Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory | Berkeley, California | |

| Oak Ridge National Laboratory | Oak Ridge, Tennessee | |

| Pacific Northwest National Laboratory | Richland, Washington | |

| Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory | Princeton, New Jersey | |

| SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory | Menlo Park, California | |

| Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility | Newport News, Virginia |

SOURCE: Adapted from Matthew Stepp, Sean Pool, Nick Loris, and John Spencer, Turning the Page: Reimagining the National Laboratories in the 21st Century, ITIF Center for American Progress and the Heritage Foundation, June 2013, Figure 1.

accountability with direct regulation of lab decisions—including hiring, worker compensation, facility safety, travel, and project management.”36 While this report is not the appropriate venue for reviewing lab management in general, it seems worthwhile to consider relevant findings of the interviews and survey.

Linking SBCs and National Laboratories

Linking SBCs and National Laboratories involves substantial structural difficulties. The latter are usually operated by government contractors—nonprofits such as Battelle—rather than directly by government staff. For the National Laboratories, even a Phase II STTR award is a small amount of money. Thus, although scientific staff may be enthusiastic about working with an SBC

___________________

36Matthew Stepp, Sean Pool, Nick Loris, and John Spencer, Turning the Page: Reimagining the National Labs in the 21st Century, ITIF Center for American Progress and the Heritage Foundation, June 2013.

TABLE 2-11 SBC-National Laboratories Collaborations Under STTR at DoE, FY 2000-2013

| Research Institution | Phase II | Phase I |

|---|---|---|

| Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory | 12 | 23 |

| Argonne National Laboratory | 8 | 21 |

| Oak Ridge National Laboratory | 8 | 16 |

| Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility | 8 | 11 |

| Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory | 5 | 10 |

| Pacific Northwest National Laboratory | 4 | 10 |

| Brookhaven National Laboratory | 6 | 8 |

| SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory | 5 | 8 |

| Los Alamos National Laboratory | 2 | 6 |

| Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory | 2 | 5 |

| Sandia National Laboratories | 1 | 3 |

| Idaho National Laboratory | 1 | 2 |

| National Renewable Energy Laboratory | 1 | 2 |

| Total SBC-National Laboratories Collaborations | 63 | 125 |

| Total number of STTR awards | 187 | 448 |

| Total number of research institution partners | 90 | 155 |

SOURCE: Data provided by DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office.

on an exciting project, administrators may see a burden rather than an opportunity. Administrative costs for the lab can effectively swallow all of the funding that might be provided to the lab under a Phase I award. In addition, although more than one-half of DoE SBIR/STTR reviewers are from the National Laboratories, these staff also play a powerful role in determining topics. DoE should consider evaluating reviews to compare scores for SBCs that do and do not collaborate with the laboratories.

Few Incentives

More generally, there are few incentives for National Laboratories to collaborate with SBCs. Sixteen of the 17 laboratories are government-owned but contractor-operated (GOCOs). In theory this arrangement provides incentives for contractors to run the laboratories efficiently while offering enhanced government oversight compared to private-sector laboratories contracted by the government. DoE staff in onsite offices oversee the laboratories, and officers approve all lab research agreements. As noted in Appendix E, Dr. Warburton (XIA), one of our case studies, said that, in the best of cases, the lab scientists view STTR as a means of supporting their research program, in exchange for providing the company with technical support. In other cases, lab staff view the program as a means to generate funds and often are not interested in commercial outcomes or even their partner’s interests.

Teaming Agreements

In addition, lab procedures are cumbersome. All teaming agreements require a cooperative research and development agreement (CRADA), and in the case of SBIR/STTR, each phase requires a separate CRADA. Furthermore, although the basic structure of the CRADA almost always follows the standard Stevenson-Wydler model contract, according to Dr. Johnson (Muons case study in Appendix E). Any change to the statement of work must be approved not only by the lab staff but also by the DoE cognizant officer who controls lab activities on behalf of DoE.

Cumbersome procedures can lead to substantial delays. In fact, as Dr. Johnson pointed out, CRADA approvals can take months. As a result, small companies working with National Laboratories must develop mechanisms for managing substantial volatility in funding flows, which could be disastrous. He also noted that delays by the lab in approving a change to the statement of work could result in the lab and the SBC working on different timelines, and therefore the lab being as much as a year behind the agreed timeline.

Other Challenges

Working with the National Laboratories presents other challenges as well. Several interviewees explained that, because the laboratories are fundamentally research organizations, they work on principles oriented around the free exchange of information and ideas, eventually leading to peer-reviewed publication of scientific and technical advances. The SBC may, however, need to maintain closer control of IP developed under an STTR award, either through patents or trade secrets, and this need to control the flow of information can create significant cultural tensions with normal lab operations. Dr. Warburton (XIA) noted that each lab has its own culture; XIA worked quite successfully with Pacific Northwest National Lab and Lawrence Livermore National Lab, but not with other laboratories.

Several survey respondents and interviewees noted that STTR agreements with National Laboratories were less enforceable than SBIR subcontracts. Under SBIR, the SBC can simply refuse to pay or switch to another supplier if the lab fails to deliver the technology or work. Whereas, under STTR, the SBC is committed to the RI for the entire Phase I/Phase II cycle and has no recourse if the RI fails to deliver. As Dr. Johnson (Muons) noted, in such circumstances, the SBC would have to do the work itself—it could not fire or sanction the RI. Dr. Warburton (XIA) said that his company’s collaboration with Brookhaven National Laboratory was especially poor, with no accountability for the project at the lab. The lab’s role was to develop a specific mechanism, but it did not deliver.37

___________________

37 See Appendix E (Case Studies).

Still, case study interviewees and 2014 Survey respondents provided cases of highly successful STTR partnerships with National Laboratories. These seemed especially likely to succeed if the SBC had a deep understanding of the lab. In several cases—such as found in the Muons case study—at least one SBC executive had worked for many years within the National Lab in question and therefore was highly knowledgeable about lab culture and procedures.

Positive Outcomes from STTR Collaborations

Finally, multiple positive outcomes from STTR collaborations with the National Laboratories were in evidence. When working with the National Laboratories, some companies view commercial success as only a component of their mission. Dr. Johnson (Muons) said that his company focuses on serving the technical needs of DoE and in particular the Laboratories, much like some SBIR companies serve DoD. He believed, based in part on his extensive experience as a lab employee, that a small firm could provide creative solutions that were difficult or impossible inside the Laboratories.38 Dr. Ives (CCR) said that his company partnered with the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory to improve the performance of cavity resonators used in linear accelerators. Stronger electric fields within the resonators means accelerators can be shorter, potentially saving millions of dollars in construction costs. However, these cost savings did not show up in the commercialization data.39

It is worth noting that some survey respondents see significant changes in the Laboratories’ attitudes toward STTR. Dr. Johnson (Muons), for example, observed that the Laboratories have traditionally viewed STTR (and SBIR) as a tax on research funding, but this perspective has changed in recent years. His view is that the Laboratories have become more interested in finding ways to use STTR (and SBIR) awards to meet their technical needs.40

CONCLUSIONS

DoE and in particular the DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office has substantially improved program management since the previous National Academies report in 2008. These improvements include:

- the shift to electronic submission

- considerably shorter time lines for applications and awards

- better connections to topic managers

- introduction of commercialization support in several areas

- perhaps the best SBIR/STTR website for applicants

___________________

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid.

40 Ibid.

- a new series of webinars which explain the application process in considerable detail

- introduction of a dedicated contracts operation

- introduction of several significant pilot programs based on best practice at other agencies (discussed in Chapter 3)

Collectively, these improvements have made a positive difference to applicants and awardees. From the point of award to the end of Phase II DoE now has what is largely a state-of-the-art operation.

Areas for potential improvement can be found prior to the Phase I award and to the end of the Phase II award. Some concerns emerge about the topics available for funding: in some cases, topics and subtopics repeat, where it may be that other areas deserve to be examined for funding. In other cases, the topics and subtopics may change too drastically to quickly to build innovation in a target area.

For EERE, the absence of open topics and the narrowness of some of the published topics means that significant opportunities for funding important innovations may be missed. The narrowness of topic definition at EERE is driven in part by the way funding is allocated across divisions and programs, and as noted in the 2008 National Academies report, this allocation may match poorly with opportunities to significant commercialization. Another factor that appears to drive the narrowness of topic definition at EERE is a deliberate effort to constrain the number of proposals. There are doubtlessly alternative, constructive methods of holding the numbers of proposals to manageable levels—while including an open topic—that are more consistent with improving the quality of proposals and enabling those with higher commercial potential. One such method used by other programs is to constrain the number of proposals per company to a level that will cause the companies to exercise greater selectivity in their submissions, while aligning submissions more closely with their technical expertise and market opportunities.

Another area for improvement is in providing a more transparent selection process that is fair both in practice and in terms of applicant perceptions. The selection criteria should be clear, easily accessible, and consistently applied; the scoring process should allow sufficient distinction among a large number of proposals to facilitate a clear ranking. Feedback to applicants should be informative and to the point.

There also possibilities for improvement after the end of Phase II. The transition to Phase III is quite challenging for many projects, and DoE should be looking for opportunities to connect SBIR/STTR projects to follow-on funding from elsewhere in DoE. This does not seem to be the case today and is therefore an area for possible improvement.