3

DoE Initiatives

Since the 2011 reauthorization of the SBIR/STTR programs, the DoE SBIR/STTR programs have initiated a number of reforms aimed at improving program outcomes and processes in the following areas:

- Outreach

- Applications and the selection process

- Support for improved commercialization outcomes

This chapter addresses each of these areas, as well as other areas where more limited progress has been made.

OUTREACH

As noted in Chapter 2, DoE recognizes that it can derive significant agency-wide value from outreach activities and the ability to attract promising companies and technologies into the program.

Electronic Outreach

During the past few years, DoE has developed an extensive outreach program organized primarily around the delivery of digital information, notably through a library of webinars and efforts to drive traffic to these resources. Since 2012 Dawnbreaker, a third-party training organization, has maintained the website on DoE’s behalf. The site offers more than 30 detailed tutorials on various aspects of the program—for example, determining whether SBIR or STTR is appropriate, understanding indirect rates, and contacting topic managers. These tutorials provide an extraordinarily detailed roadmap for addressing a range of issues. For example, the tutorial on contacting the Topic Manager (TM) explains why this step is important, the best ways to contact the TM, a preparatory chart to prepare for a phone call, and a number of explanatory

video clips. Although it is, according to program staff, often difficult to persuade potential applicants to take full advantage of the available material, DoE has developed an impressive library of materials supporting outreach. Applicants who use them will be well positioned, other things equal, to improve their chances of obtaining funding.

In early 2013, the Program Office started two webinar series. The first, which focuses on specific technology areas, is led by TMs and therefore provides companies with a direct connection to DoE specialists. The second focuses on funding opportunities, in particular application-related questions. In 2015, the Program Office started another series that focuses on the more technical aspects of application budgeting, beginning with indirect rates. According to Program Office staff, these three series of webinars are a highly efficient way of reaching new applicants and providing answers to questions from both new and returning would-be applicants.

All webinars are archived on the DoE website, and SBIR/STTR program management notes that playback of archived webinars has proven to be a useful outreach tool because more viewers playback webinars than attend live webinars. Table 3-1 shows the take-up of webinar offerings during FY 2014 and FY 2015. DoE offered seven webinars in FY 2014 and nine in FY 2015. More than 2,000 participants attended the webinars live, and approximately 3,500 viewed the webinars through the playback mechanism. Compared to professional conferences, where program management often has limited access to participant lists and relies on the collection of business cards or similar small-scale outreach, webinars—the lists of those who accessed outreach materials by attending live webinars and watching outreach materials via recorded webinars made available through playback—provided for a more direct connection of TMs to potential applicants.

More generally, Program Office staff believe that the web-based focus is highly efficient in terms of reaching potential applicants and providing clear and specific information, compared to more traditional forms of outreach.

Phase 0

As of September 2014, DoE is providing additional support for new applicants through a pilot Phase 0 program, funded through the SBIR Administrative Fund Pilot program. The program is explicitly designed to enhance the participation of underrepresented groups, defined by DoE as

- underrepresented states,

- woman-owned businesses, or

- minority-owned businesses1

___________________

1 DoE uses the definition of “minority” provided by SBA, which is discussed further in Chapter 6 of this report.

TABLE 3-1 Numbers of Potential Applicants Attending DoE Webinars or Viewing Them Via Playback, FY 2014-2015

| Year Title | Date | Number of Potential Applicants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered Attended Playbacks | |||||

| FY 2014 | FY14 Phase I Rel 1 Topics 29-40 (HE/NP) | 7/24/2013 | 164 | 64 | 30 |

| FY14 Phase I Release I FOA | 8/16/2013 | 504 | 295 | 321 | |

| FY14 Sequential Phase II Rel 1 | 10/30/2013 | 91 | |||

| FY14 Phase I Rel 2 Topics 1-8 & 22 | 11/4/2013 | 228 | 144 | 361 | |

| FY14 Phase I Rel 2 Topics 10-21 | 11/5/2013 | 92 | 63 | 150 | |

| FY14 Phase I Release 2 FOA | 12/3/2013 | 486 | 285 | 178 | |

| FY14 Sequential Phase II Rel 2 | 2/20/2014 | 44 | 35 | 32 | |

| Total | 1,518 | 886 | 1,163 | ||

| FY 2015 | FY15 Phase I Rel 1 Topics 1-16 | 7/22/2014 | 453 | 294 | 307 |

| FY15 Phase I Rel 1 Topics 19-26 | 7/23/2014 | 263 | 124 | 125 | |

| FY15 Phase I Release 1 FOA | 8/15/2014 | 310 | 169 | 213 | |

| FY15 Phase I Rel 2 Topics 1-9 | 11/4/2014 | 133 | 61 | 50 | |

| FY15 Phase I Rel 2 Topics 20-25 | 11/5/2014 | 144 | 67 | 36 | |

| FY15 Phase I Rel 2 Topics 26-33 | 11/6/2014 | 129 | 71 | 117 | |

| FY15 Phase I Rel 2 Topics 10-19 | 11/7/2014 | 377 | 186 | 384 | |

| FY15 Phase I Release 2 FOA | 12/1/2014 | 360 | 237 | 1,013 | |

| FY15 Phase II Release 2 FOA | 2/1/2015 | 51 | 37 | 56 | |

| Total | 2,220 | 1,246 | 2,301 | ||

SOURCE: DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office.

The program is “modeled after and carried out in conjunction with” state Phase 0 programs.2 Managed by Dawnbreaker under a $1 million annual contract, the program provides a range of services to applicants who meet one of the four target criteria listed in Chapter 2; have not received a DoE SBIR/STTR award during the past 3 years; and have not received technical assistance for a similar technology from DoE for the past 2 years.3

Services are available once the Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) has been published by DoE and on a first-come, first-served basis until funding is exhausted. According to Dawnbreaker, the program is expected to

___________________

2 Manny Oliver, “Improving DOE’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs,” presentation to National Academies, October 20, 2015. See also National Research Council, Workshop on “SBIR/STTR & the Role of State Programs,” Washington, DC, October 7, 2014.

3 DoE identifies the following states as underserved: AK, DC, GA, HI, IA, ID, IN, KS, LA, ME, MN, MS, MT, NC, ND, NE, NY, OK, PA, PR, RI, SC, SD, WA, WI.

serve between 40 and 100 eligible applicants per release. Services are free of charge to the participating company and fall into the following categories.

- Letter of Intent (LOI) review. DoE is unique among the other agencies in requesting a 500 word LOI, due approximately 1 month after release of the FOA. Dawnbreaker assists applicants in developing a well-developed, two-page description of the technology and its application.

- Phase I proposal preparation, review, and submission assistance. Dawnbreaker provides program applicants with a coach who provides initial advice; helps the company establish and maintain a schedule for proposal preparation; and provides feedback as an independent reviewer of the draft proposal.

- Market research assistance. Although DoE requires only limited commercialization plans for Phase I applications, it requires revenue projections over a 10-year period. A preliminary market assessment may provide companies with insights into different potential applications, or identify the existence of strong competing products already in the market. According to Dawnbreaker, eligible applicants may be provided with one relevant Frost and Sullivan report.

- Small business development training and mentoring. The Dawnbreaker business coach can align services with the company’s needs. For example, newly formed companies may require assistance with firm structure and initial sources of support. More established firms might require guidance on business models and strategies. Technical leaders of newly formed companies may not yet be experienced in effectively presenting their ideas to investors, and Dawnbreaker’s coaching and advice may help.

- Technology advice and consultation. The program provides up to 3 hours of technical consultant time for feedback on the technical work plan or other technical issues.

- Intellectual property consultation. Because even a Phase I proposal requires some attention to intellectual property, the program provides access to legal counsel.

- Indirect rates and financials. To prepare a budget, an applicant must address the issue of indirect rates. The Dawnbreaker consultant helps applicants to understand indirect rates and to develop an appropriate rate structure for the DoE proposal, although the budget itself is prepared by the applicant.

- Travel assistance. Small business can be reimbursed for pre-approved, relevant travel expenses subject to federal travel guidelines. The travel must be germane to securing a Phase I SBIR/STTR award. This component is primarily aimed at supporting travel to meet with staff at DoE or the National Laboratories.

It is too early to develop definitive conclusions about the DoE Phase 0 program, and initial data are mixed. Table 3-2 summarizes participation and milestone achievement for the first intake of Phase 0 participants for DoE’s spring 2015 solicitation. Of the 69 initial participants, 54 developed LOIs that were deemed responsive, and all subsequent awardees were among this group. Dawnbreaker provided help to all participants. Eventually, 47 of the 69 applied for funding, and 7 were successful. Because the average overall success at DoE is 18 percent, 7 awards from 47 applications is not an unusual result. A further breakdown (not shown in the table) reveals that 4 of the 7 awards were from companies located in underrepresented states. No awards were to woman-owned firms, and the three minority-owned firms were Asian owned, so there were no awards for firms owned by African Americans, Hispanic Americans, or Native Americans.

The first round of Phase 0 focused primarily on supporting companies that were new to the program and were already interested in applying. Manny Oliver, SBIR/STTR Program Manager, indicated that, if possible, subsequent rounds will seek to attract new participants, especially from underrepresented groups, who have not yet contacted the program.

TABLE 3-2 Participation and Milestones for DoE Phase 0, Spring 2015

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Total Phase 0 Participants | 69 | ||

| Participants with Responsive LOIs | 54 | 78% | (of Total Participants) |

|

Applied |

41 | 76% | (of Responsive) |

|

No LOI Support |

21 | 39% | (of Responsive) |

|

Other Phase 0 Support |

20 | 37% | (of Responsive) |

|

Did Not Apply |

13 | 24% | (of Responsive) |

|

No LOI Support |

2 | ||

|

Other Phase 0 Support |

12 | ||

| Unresponsive | 15 | 22% | (of Total Participants) |

|

Applied |

6 | 40% | (of Unresponsive) |

|

No LOI Support |

3 | 20% | (of Unresponsive) |

|

Other Phase 0 Support |

3 | 20% | (of Unresponsive) |

|

Did Not Apply |

9 | 60% | (of Unresponsive) |

|

No LOI Support |

2 | ||

|

Other Phase 0 Support |

7 | ||

| Applied | 47 | 68% | (of Total Participants) |

| Did Not Apply | 22 | 32% | (of Total Participants) |

| Awards | 7 | 10% | (of Total Participants) |

SOURCE: DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office.

APPLICATION AND SELECTION PROCESS

During the past few years, DoE has made a number of changes to the application and selection processes. Taken together, these changes constitute a significant improvement in the process for many applicants, although in some cases they raise concerns about program balance between commercialization and innovation, and between outreach to increase applications and constraints to limit applications. They also raise concerns about the balance between managing reviewer loads and applicant perceptions of transparency and fairness.

Increased Commercialization Emphasis

DoE has placed an increasing emphasis on commercial outcomes from SBIR/STTR, as reflected in several areas. TMs are encouraged to ensure that their subtopics will support technologies that are commercially viable. This emphasis is also expected to be reflected in the applications themselves (this important issue is discussed in Chapter 2). Phase I applicants are now required to provide a commercialization plan that is sufficiently detailed to estimate technology-related revenues 10 years into the future, an approach identified by DoE as a best practice initiated at the National Science Foundation (NSF). Several companies interviewed for case studies observed that such projections will likely be highly inaccurate and that Phase I is designed to establish technical feasibility, long before commercialization occurs. However, other case study interviewees suggested that focusing on commercial targets at the earliest stage has important benefits: the increased emphasis on commercialization may encourage some companies to be more selective in the subtopics they pursue.

Phase II applicants are now required to provide a much more detailed and extended commercialization plan, including specific revenue calculations, which is reviewed by commercialization experts hired by DoE. Although there were some complaints about the quality of these reviews, the new process underscores DoE’s expectation that SBIR/STTR projects in Phase II will focus on commercialization.

Not meeting the new commercialization requirements can block further funding for a company. The process generates several potential “red flags” of applications with low commercial potential:

- Poor commercialization history

- Low revenue forecast (based on Phase I commercialization plan)

- Low commercial potential review score (based on Phase II commercialization plan)

Applications with red flags are ineligible for funding unless a DoE program manager provides sufficient justification. Because solicitations are highly competitive, it seems likely that red flags will result in exclusion from funding.

Finally, DoE has adopted another best practice, this time from NASA: it now limits companies to no more than 10 applications per solicitation. This change has according to case study interviewees made an impact; some welcomed it because it forced them to focus on their most promising technologies.

Fast Track

In FY 2013, DoE implemented a Fast Track program similar to that in place at NIH. Under Fast Track, companies can apply for a unified Phase I-Phase II award, in which Phase II proceeds automatically if the company meets predetermined technical milestones.

The program is designed to help companies accelerate development by eliminating the gap between Phase I and Phase II. The DoE Fast Track program allows for 6 to 9 months for Phase I activities and 24 months for Phase II activities and requires a Phase II commercialization plan (the Phase I plan is not required). DoE notes that this approach may not be suitable for companies with limited commercialization experience. Some topics, notably those from the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE), do not permit Fast Track.

The advantages of Fast Track are obvious—companies can work under less uncertainty, and, where implemented, Fast Track has the effect of eliminating the average 5-month gap between the end of Phase I and the beginning of Phase II at DoE.

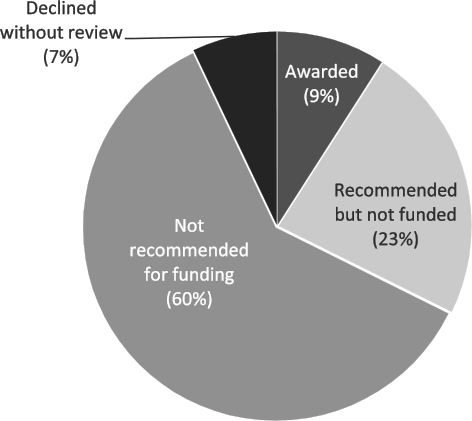

DoE Fast Track covers only 3 to 5 percent of DoE SBIR/STTR awards. DoE Fast Track applications have a success rate about one-half that of Phase I applications (9 percent). Also, a higher percentage of Fast Track awards than of Phase I applications are recommended but not funded (23 percent of DoE Fast Track are recommended but not funded) (See Figure 3-1).

Improved Process Timelines

DoE has made a concerted effort to improve processing timelines for both Phase I and Phase II. In part an effort to meet statutory guidelines under reauthorization and Small Business Administration (SBA) policy guidance, the changes also increase the time available to companies to develop their ideas and establish collaborations after the topics are published.

Figures 3-2 and 3-3 were deleted at press time. These figures were originally on pages 76 and 77, which are now intentionally blank to avoid renumbering the entire report.

SOURCE: DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office.

The compressed schedule has important immediate benefits: (1) companies with limited resources do not have to wait as long for funding flows to begin, and (2) the additional time between the funding announcement and the application deadline allows companies to generate better quality applications.

Much of the improvement can be attributed to the establishment of a dedicated SBIR/STTR contracts team with seven full-time staff in the DoE Chicago offices. Prior to this change, contracts were often handled by staff with little experience or training with SBIR/STTR awards, which frequently resulted in more difficult negotiations and unnecessary delays. The new dedicated team has significantly streamlined the process.

SUPPORT FOR IMPROVED COMMERCIALIZATION OUTCOMES

DoE has a taken several steps to improve commercialization outcomes from the SBIR/STTR programs.

Sequential Phase II Awards

Since FY 2014, DoE has taken advantage of the new flexibility provided under the 2011 congressional reauthorization to offer sequential

This page intentionally left blank.

This page intentionally left blank.

Phase II awards. Sequential Phase II awards are aimed at providing additional R&D funding for mature existing Phase II promising technologies that are not yet ready for the market. DoE provides two kinds of sequential Phase II awards:

- Phase IIA provides the small business concern (SBC) with a small amount of additional funding to complete a Phase II project that was not completed by the original award expiration date.

- Phase IIB is modeled on Phase IIB at other agencies, notably NSF and NIH, and is designed to provide more substantial transition funding. However, unlike NSF, which requires Phase IIB SBC applicants to secure matching funds from other sources in order to be eligible for the NSF IIB grant, DoE Phase IIB awards do not require matching funds of any kind from the SBC.

Technology Transfer Opportunities (TTOs)

DoE has made new efforts to support technology transition from National Laboratories to the commercial marketplace. In FY 2013, DoE began to set aside a number of awards for Technology Transfer Opportunities (TTOs): subtopics for which National Laboratories offer technologies that could be appropriate for transition, designed to attract SBCs as commercialization partners. In contrast, most National Laboratories’ participation in SBIR has been limited to providing technical expertise and equipment to SBCs as they develop and test their technologies.

TTOs are published in the standard SBIR/STTR solicitation, but these are more tightly focused than standard topics. This is not surprising because TTOs are designed for a technology that already exists and could be commercialized, rather than a technology that is needed but not yet developed. Awardees benefit both from the SBIR/STTR award and from a license to the technology provided through DoE.

Table 3-3 shows the adoption of the TTO pathway since its inception in FY 2013. Many TTOs do not result in an award and only a small percentage result in a Phase II award. It will be worth considering whether participation is useful for National Laboratories as the program evolves over time.

TABLE 3-3 Adoption of TTOs by SBCs at DoE through the SBIR/STTR, FY 2013-2015

| TTO subtopics | FY I Awards | FY II Awards | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FY 2013 | 18 | 2 | 0 |

| FY 2014 | 33 | 8 | 1 |

| FY 2015 | 31 | 8 | 3 |

SOURCE: DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office.

SBIR/STTR Assistance for Commercialization/Marketing

A company has two options for obtaining assistance from SBIR/STTR to develop its commercialization/marketing efforts: (1) It can choose to participate in the DoE Commercialization Assistance Program (CAP), or (2) it can choose instead to apply for a lump sum amount (currently $5,000) per Phase I award to spend on its own commercialization/marketing efforts. The second option, Opting out of the CAP, was newly offered under the December 2011 reauthorization, and must be done prior to a company submitting its Phase I application. Approximately 95-98 percent of DoE awardees have chosen to participate in CAP, while 3-5 percent have chosen to Opt-out of CAP and take the lump-sum amount.

Commercialization Assistance Program

DoE has steadily improved CAP, which it offers through a third-party contractor, Dawnbreaker.4 Currently, all assistance for CAP is provided by Dawnbreaker through two support contracts (approximately $2.5 million, through administrative pilot program funding). Under Dawnbreaker’s current contract, which expires in March 2017, participating companies can access the services they need up to a budget of $5,000 annually per project, which is paid by DoE to Dawnbreaker once the selected services have been delivered.

This pay-for-service model replaced a previous effort that simply provided a lump sum to Dawnbreaker on an annual basis. The new model incentivizes Dawnbreaker to actively market its services to SBIR/STTR companies, and to make sure that the services are tailored to the specific needs of the company—a startup is, for example, likely to have very different needs than an established company seeking to enter a new market. Money remaining in the $5,000 annual budget per project that is not spent on Dawnbreaker services is returned to the SBIR/STTR programs at DoE, and funding from the first year of a Phase II award cannot be rolled over into the second year.

Phase I CAP Assistance

Phase I assistance focuses on providing a Commercialization Readiness Assessment, which is primarily designed to help the company develop an effective commercialization plan for its Phase II proposal. The start of Phase I services is deliberately delayed, to permit companies to focus primarily on their

___________________

4 Dawnbreaker, founded by Dr. Jenny Servo in 1990, provides a range of services to federal agencies and to small businesses. It has worked with more than 7,500 companies in both civilian and defense markets.

R&D during the initial stages of Phase I. The CAP begins about 5 months before Phase II applications are due.5

A Business Acceleration Manager is assigned from Dawnbreaker to each participating company, and after each company signs Dawnbreaker’s Non Disclosure Agreement (NDA), approved by DoE, it can receive services which can include:

- A Commercialization Readiness Assessment (CRA)

- Market Research

- Series of Specialty Webinars

- Business mentoring organized around the development of the Phase II Commercialization Plan (CP)

A focus is to assist the companies to develop the 15-page commercialization plan for inclusion in the Phase II application.

Phase II CAP Assistance

A much more extensive menu of options is available from Dawnbreaker for Phase II awardees. The extensive menu of available service items includes some items that are rarely used. DoE has not asked Dawnbreaker to remove the rarely used items on the grounds that if the capacity is available, it may be useful for a few companies even if it is not a core service. Services that are used less frequently include:

- Financials assessment (scientists prefer to avoid this)

- Licensing and negotiating IP (companies may not be ready for this)

- Development of a trade show booth (trade shows are much less popular now)

According to DoE staff, services used by almost all Phase II program participants include:

- Additional Commercialization Readiness Assessment (CRA). This provides information needed to select other services.

- Frost and Sullivan marketing reports

- Market research (primary and customized)

- Competitor analysis

- Business mentoring (a maximum number of hours are provided)

- Developing network contacts

___________________

5 Dawnbreaker, DOE SBIR/STTR, Commercialization Assistance Program (CAP): Services ForPhase I and Phase II Awardees, http://science.energy.gov/~/media/sbir/powerpoint/DOE_CAP_Overview_Presentation.pptx, accessed November 14, 2015.

Dawnbreaker, in association with DoE, also introduces new or expanded services as demand changes. For example, companies have in recent years sought help to develop more professional websites, a service that is now available to them.

In general, the services are expected to provide the assistance that companies need to be able to step up and improve their capacity, rather than leaning on Dawnbreaker for an extended period. DoE program staff noted that $5,000 annually is not sufficient to provide a higher level of service and that there are benefits to encouraging firms to take responsibility for commercialization themselves. Thus, for example, Dawnbreaker provides introductions of companies to potential investors, but that is the extent of their support in that area.

Effectiveness of the Commercialization Assistance Program

There are three sources of data on general program outcomes and on commercialization that, together, can shed light on the effectiveness of CAP: (1) Dawnbreaker summary reports of data from surveys it conducts 6, 12, and 18 months after the end of Phase II on commercialization results (not publicly available), (2) reports on commercialization outcomes required of companies for all previous SBIR/STTR projects (including those funded by other agencies) when applying for DoE SBIR/STTR funding, and (3) a DoE annual survey conducted from FY 2012 to FY 2014 of all Phase II awardees 5 years after the initiation of Phase I (i.e., approximately 2 years after the conclusion of the Phase II award).6

So far, there is no conclusive information about the impact of the CAP. One reason is that, until recently, the DoE SBIR/STTR Program Office has not had the manpower available to undertake a detailed analysis of the data. Moreover, DoE did not wish to over rely on the summary raw data compiled by Dawnbreaker about its own effectiveness. However, as new staff members have been hired, we are informed that DoE now plans to undertake an evaluation of CAP.

Despite the limited information about the impact of the CAP, the wide menu of available services and the use of a third-party provider with extensive expertise in this area appear to be positive steps. Furthermore, the use of an innovative contracting structure to incentivize the provider is, we believe, unique among SBIR/STTR agencies, and seems another promising step. The expected improvement in data collection and analytics related to the commercialization program and quantitative analysis of the data would be an additional welcomed and positive step toward understanding CAP effectiveness.

___________________

6 This DoE annual survey required and received approval from the Office of Management and Budget pursuant to the Paperwork Reduction Act.

OTHER INITIATIVES

DoE is the first agency to take advantage of the flexibility provided by the reauthorization legislation to permit companies to use up to $15,000 in Phase II funding for patenting expenses. This is a significant initiative, and one that company case study interviewees welcomed. Because the cost of patenting new technology can be prohibitive for small businesses, especially when they have not yet generated revenue, this initiative is potentially valuable.

CONCLUSIONS

The initiatives described in this chapter, many drawing from best practices at other agencies, reflect efforts to improve the DoE SBIR/STTR programs. Fast Track, Phase IIB, and third-party commercialization support were adopted directly from NSF, and Phase IIA closely resembles the availability of supplementary funding at NIH. Another beneficial initiative has been the introduction of an open period between the release of topics and the FOA (similar to a practice at the Department of Defense). The open period permits companies to explore possible applications in detail with technical staff.

DoE has also developed its own initiatives. These include the division of the solicitation into two releases annually, which has been an important facilitator of the compressed timelines and improved efficiency. The use of two releases allows DoE to assign dedicated staff to the contracting process. DoE’s electronic outreach is state of the art and a potentially important model for other agencies. The extensive use of webinars is unique among the major SBIR/STTR agencies, and DoE’s approach to outreach is appropriate and likely to be both cost-effective and successful. DoE’s use of letters of intent is a further innovation used for topic identification. A similar program exists at NSF, although perhaps with different program objectives. Survey responses and interviewee comments indicate that SBCs approve of the LOI process, and the data show that, in addition to identifying topic/subtopic, the LOI process inadvertently also has been found to be a way to reduce the burden on both reviewers and companies as it serves to reduce the number of applications.7

Finally, it is anticipated that evidence about the overall effectiveness of CAP will soon become available.

___________________

7 As was noted in Chapter 2, constraining the number of applications per company would seem a more efficient and less biasing method of limiting the number of applications while raising quality and facilitating commercialization than over-constraining topics and subtopics in conjunction with the LOI to reduce applications.