1

Introduction

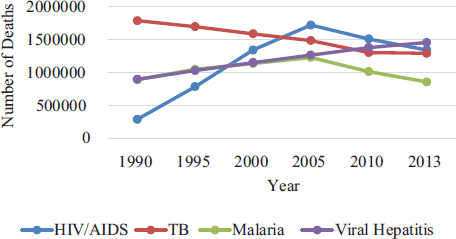

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver, often caused by a virus. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) cause the majority of hepatitis in the United States and worldwide. The two diseases together account for more than 1 million deaths per year, including 78 percent of the world’s hepatocellular carcinoma, the most common type of liver cancer, and 55 percent of fatal cirrhosis (WHO, 2016b). In 2013, viral hepatitis surpassed HIV and AIDS to become the seventh leading cause of death in the world (WHO, 2016a) (see Box 1-1 and Figure 1-1). Table 1-1 gives more information on the key characteristics of the two diseases.

SOURCE: IHME, 2016.

TABLE 1-1 Key Characteristics of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C

| Hepatitis B | Hepatitis C | |

| Causative Agent | Partially double-stranded DNA virus | Enveloped, positive-strand RNA virus |

| Hepadnaviridae family | Hepacavirus genus, Flaviviridae family | |

| Statistics | In the United States, there are an estimated 0.7-1.4 million people chronically infected with HBV, with approximately 19,800 new infections every yeara | In the United States, there are an estimated 2.7-4.7 million people chronically infected with HCV, with approximately 29,700 new infections every yeara |

| Routes of Transmissiond | Contact with infectious blood, semen, and other body fluids; transmitted througha

|

Contact with infectious blood, primarily througha

|

Less commonly throughc

|

||

Less commonly through

|

||

| Persons at Riskd |

|

|

| Hepatitis B | Hepatitis C | |

| Persons at Risk (continued) |

|

|

| Potential for Chronic Infection |

Among newly infected, persons, chronic infection occurs inb

|

Chronic infection develops in 75-85 percent of newly infected personsc |

| Clinical Outcomes | ||

NOTES: HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus. d In no particular order.

SOURCES: Adapted from IOM, 2010, with updated information from a CDC, 2015e; b CDC, 2015a; c CDC, 2016.

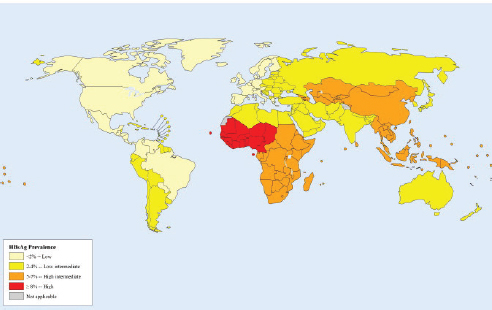

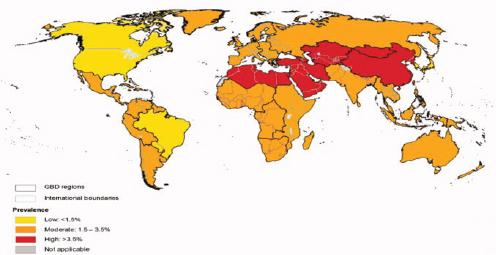

THE GLOBAL BURDEN OF HEPATITIS B AND C VIRUS INFECTIONS

The prevalence of chronic hepatitis B is highest in East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (see Figure 1-2), where people are commonly infected via mother-to-child transmission at birth, or in early childhood through exposure to infected blood usually from an infected family member or another child. In places with a low prevalence of hepatitis B, such as North America and Western Europe, the virus is more commonly transmitted through injection drug use and unprotected sex, while immigrants from hepatitis B-endemic countries are the major source of chronic infection. Chronic hepatitis C is most prevalent in the Middle East and Asia (see Figure 1-3), where unsafe medical injection and transfusion practices are the major source of infection. In North American and Western Europe, injection drug use is the main transmission route for HCV infection.

SOURCE: Ott et al., 2012.

NOTES: Estimates are derived from a meta-analysis of data from 232 studies published between 1997-2007 and NHANES data up to 2010. Point prevalence estimates are calculated using regional population age weights.

SOURCE: Mohd Hanafiah et al., 2013.

Viral Hepatitis in the United States

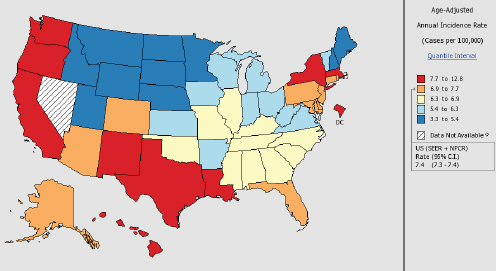

In the United States hepatitis B and C accounted for about 20,000 deaths annually between 2009 and 2013 (CDC, 2013). The CDC estimates that between 700,000 and 1.4 million people have chronic hepatitis B in the United States; the same source gives a chronic hepatitis C prevalence of 2.7 to 3.9 million, though both estimates are thought to be low (CDC, 2011, 2015b). The two diseases together account for over a third of liver transplantations (Luu, 2015). By 2013 estimates, the viruses cause an estimated 61 percent of the nation’s hepatocellular carcinoma, the most common form of liver cancer (IHME, 2016). Liver cancer, in turn, is the fastest rising cause of cancer deaths in the United States; its incidence has tripled since the early 1980s (El-Serag and Kanwal, 2014). While Asian-American men have the highest age-adjusted incidence of liver cancer, other ethnic groups have seen rapid proportional increases, as have people aged 45-60, and people in southern states (see Figure 1-4).

Action against hepatitis B and C is difficult, in part because the diseases are often asymptomatic until the later stages. Research suggests approximately two-thirds of people infected with hepatitis B are not aware of their

NOTES: Created by statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov on 01/11/2016 8:58 am. Data on the United States does not include data from Nevada. State Cancer Registries may provide more current or more local data. Data presented on the State Cancer Profiles website may differ from statistics reported by the State Cancer Registries.

† Incidence rates (cases per 100,000 population per year) are age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population (19 age groups: <1, 1-4, 5-9,… 80-84, 85+). Rates are for invasive cancer only (except for bladder which is invasive and in situ) or unless otherwise specified. Rates calculated using SEER*Stat. Population counts for denominators are based on census populations as modified by National Cancer Institute. The 1969-2013 population data is used incidence rates.

Data not available for this combination of geography, statistics, age and race/ethnicity.

Data not available for this combination of geography, statistics, age and race/ethnicity.SOURCES: State Cancer Registries, 2016; U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2016.

condition (Cohen et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2007). Similarly, about half of those infected with hepatitis C are unaware of their condition (Volk et al., 2009). Without medical management and appropriate antiviral treatment, chronic hepatitis B carries a 15 to 25 percent risk of serious liver conditions (CDC, 2015a). Over time, chronic hepatitis C greatly increases risk of death. Over 18 years of follow-up, the liver-related mortality rate for chronically infected HCV patients is more than 12 percent, compared to less than 1 percent for people without chronic HCV infection (Lee et al., 2012). Chronic hepatitis B or C also increases the risk of liver cancer (Lai and Yuen, 2013).

To complicate the matter, chronic hepatitis B and C take a disproportionate toll on minority groups and the foreign-born, for whom there may be barriers to seeking treatment. Half of all hepatitis B patients in the United States are Asian-American or Pacific Islander, though this group accounts for only about 5 percent of the population; among African immigrants the prevalence of infection is about 1 in 10 (HHS, 2014; Hoeffel et al., 2012; Mitchell et al., 2011). Hepatitis C infection shows similar disparities. American Indians and Alaskan Natives have the highest incidence of acute hepatitis C of any racial or ethnic group, and African-Americans, who make up only 12 percent of the US population, account for 22 percent of chronic hepatitis C infections (CDC, 2013; HHS, 2014). Viral hepatitis can affect people marginalized in other ways. The use of injection drugs is the principle risk factor for hepatitis C (Zibbell, 2015). Though it is difficult to estimate the disease burden among people who inject drugs, recent surveys among active drug injectors suggest about a third of those under 30 and as many as 70 to 90 percent of those over 30 have chronic hepatitis C (CDC, 2016).

A vaccine against hepatitis B has been available since the 1980s, though the most recent national survey suggests adult coverage rates of only 25 percent (CDC, 2015d; Chen, 2010). Developments in curative therapy for hepatitis C are more recent. As of 2014, oral, direct-acting antiviral regimens of relatively short duration make cure1 possible in 95 percent of patients and are associated with few adverse effects (Feld et al., 2015; Foster et al., 2015). Together these advances have encouraged global interest in action against viral hepatitis, reflected in the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, which mention viral hepatitis, along with HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria, as a disease to be actively combatted by 2030 (United Nations, 2014). The World Health Assembly has issued two statements on viral hepatitis in only three years; in 2014 member states requested that the World Health Organization (WHO) examine the feasibility of hepatitis B and C elimination (World Health Assembly, 2014). By January 2016, 24 countries had developed national viral hepatitis actions plans; 19 other countries have plans in development (WHO, 2016a).

___________________

1Sustained virologic response and cure are used synonymously. When interferon treatments were standard of care for hepatitis C, sustained virologic response was defined as negative viral load 24 weeks after cessation of therapy. With direct-acting antivirals, this timeframe is shortened to 12 weeks. The 12-week mark is recognized as the endpoint for cure by the Food and Drug Administration because of the high concordance between sustained virologic response at 12 and 24 weeks (FDA, 2013).

THE COMMITTEE’S CHARGE

The elimination of hepatitis B and C is a topic of particular concern to the Division of Viral Hepatitis at the CDC and the Office of Minority Health in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The US government’s 2014 interagency action plan on viral hepatitis lays out four national goals to be achieved by 2020, shown in Box 1-2. Both offices are involved in the global discussion on hepatitis B and C elimination and also work on elimination programs for specific populations, including the elimination of hepatitis C from the Cherokee Nation and the Republic of Georgia (Mitruka et al., 2015). Given this context and the growing international momentum for action against viral hepatitis, the offices sought guidance from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on the feasibility of eliminating hepatitis B and C from the United States.

The study sponsors directed the committee to work in two phases and produce two reports. This report, the first of the pair, examines the feasibility of hepatitis B and C elimination in the United States. The phase two report, to be published in 2017, will outline a strategy for meeting the elimination goals discussed in this report. Box 1-3 shows the statement of task for both projects, though this report is limited to the phase one task.

The Committee’s Approach to Its Charge

To address the charge laid out in Box 1-3, the committee reviewed the available evidence on the burden of hepatitis B and C, the screening, treatment, and management of chronic infection, and scientific and logistical ob-

stacles to elimination. They drew on published literature and presentations from expert speakers as well as information about federal and state viral hepatitis programs. Members of the public submitted written testimony to the committee, which was also taken into account (available from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Public Access Records Office, PARO@nas.edu).

The committee met twice to prepare this report; see Appendixes A and B for the meeting agendas. In closed session, the group evaluated the evidence and deliberated on the feasibility of eliminating hepatitis B and C from the United States; members discussed the implications and feasibility of disease control, elimination, and eradication goals. Based on expert opinion, the committee came to conclusions regarding the feasibility of disease elimination. As the two diseases have widely different viral origins, natural histories, epidemiological features, and clinical management, the committee dealt with the elimination question separately for each disease. The remainder of this chapter gives background and context for understanding disease elimination and explains the committee’s conclusions about a suitable disease elimination goal. Chapter 2 discusses hepatitis B elimination, and the critical factors necessary to end transmission and reduce morbidity and mortality from the disease. Chapter 3 deals with the same questions for hepatitis C.

DISEASE CONTROL, ELIMINATION, AND ERADICATION

The elimination of important infectious disease from society is a goal dating to at least the eighteenth century, when Edward Jenner envisioned ridding the world of smallpox through widespread vaccination. Programs initiated in the early and middle parts of the 20th century to eradicate yellow fever, yaws, and malaria, while unsuccessful, improved understanding of the epidemiological and biological features that make a disease a candidate for eradication. When, in 1966, the World Health Assembly resolved to eradicate smallpox from the Earth, it was clear that eradication meant preventing any new cases of smallpox in the world; the surveillance and documentation system developed to support that goal left no room for a single infection.

Smallpox eradication emboldened policy makers; it seemed at the time that other human and animal diseases might be equally susceptible (Hopkins, 2009). In 1988, the International Task Force on Disease Eradication began systematic evaluation of the qualities that make a disease eradicable (The Carter Center, 2016b; Tulchinsky and Varavikova, 2009). In addition to scientific characteristics of the disease and available countermeasures, the group weighed social considerations such as political will and perceived burden of disease (see Box 1-4). After reviewing 94 infectious diseases, they found only six2 suitable for eradication (CDC, 1993). None of these has since been eradicated, though guinea worm disease is close (The

___________________

2 Guinea worm disease, polio, lymphatic filariasis, mumps, rubella, and pork tapeworm.

Carter Center, 2016a). The discussion also quickly made it clear that different people could have widely different ideas of what disease eradication, elimination, and control might mean, raising interest in standard definitions of the relevant terms.

Clarifying the hierarchy of different public health efforts was a goal of the 1998 Dahlem Conference, which proposed mutually exclusive definitions for terms relevant to disease eradication. These definitions overlap with those of the earlier task force, especially in their understanding of disease eradication and control (both shown in Box 1-5). The Dahlem definitions emphasize the zero goal of disease elimination, while the earlier understanding left room for controlling the disease to the point of no longer being a public health problem.

In 2010, another expert panel revisited the concepts of disease elimination at the request of the WHO Executive Board (WHO, 2010). But

since that meeting, the use of the terms defined in Box 1-5 has grown only more inconsistent. Such confusion causes problems in program evaluation. Without a clear idea of the level of control sought, it is difficult to judge a program’s progress, or even know what information the surveillance system should supply. In the smallpox example, the goal of no new cases without continued vaccination was possible because of the disease’s recognizable clinical presentation, the lack of chronic infection or silent transmission, the absence of a nonhuman reservoir in nature, and the availability of a highly effective vaccine. On the other hand, the Pan American Health Organization’s measles elimination program, which aimed to end measles transmission in the Americas, recognized that endemic measles in other parts of the world would inevitably lead to periodic reintroduction to the Americas (Andrus et al., 2011). The program therefore needed a sensitive surveillance system and a laboratory network for distinguishing endemic cases from imported ones. Similarly, ongoing work in global polio eradication struggles with asymptomatic infection and silent transmission, to say nothing of the difficulty distinguishing wild-type virus infection from vaccine-derived infection. Measuring the success of both measles and polio eradication depend on sophisticated virological surveillance.

The elimination of viral hepatitis poses its own challenges, both in defining what qualifies as elimination and in monitoring progress toward the goal. Both HBV and HCV can be cleared after introduction by the host’s immune response. Among those people who acquire chronic infection, the majority of cases become clinically apparent only decades later. For these reasons, as well as those discussed earlier (the diseases’ different origins, natural histories, epidemiological features, and clinical management), it is necessary to consider the feasibility of eliminating acute infection, chronic infection, and the clinical sequelae of such infections (including liver disease, liver cancer, and death) separately for each disease.

It is also important to remember that both viruses are endemic abroad, so their elimination from the United States would exist against a background of constant reimportation. Perfect vaccination could, in theory, eliminate transmission of HBV, but it would take two generations. In the meantime, there is no cure for the millions of people already infected. The new direct-acting antivirals that cure HCV infection are increasingly available, but still unlikely to reach all of the world’s hepatitis C-infected people anytime soon. Any strategy to eliminate hepatitis B and C from the United States would also have to account for the imported cases and for transmission attributable to people born abroad.

In setting elimination goals for hepatitis B and C, the committee considered the challenges of identifying prevalent and incident cases and the related problem of monitoring progress toward the goal of disease reduc-

tion. It also acknowledged the devastating consequences of both infections and the power of the global momentum for action against viral hepatitis. With this in mind, the committee concluded that disease control—defined as a reduction in the incidence and prevalence of hepatitis B and C and their sequelae with ongoing control measures required—is feasible in the relatively short term. It also saw value in setting a goal to eliminate the public health problem of these diseases; in this case, elimination refers to cessation of transmission in the United States, allowing that the infections may remain but their particularly undesirable clinical manifestations prevented entirely. In its discussion of elimination the committee emphasized reducing the manifestations of HBV and HCV infection to a level that is no longer a public health problem. For the committee’s purposes, a public health problem may be defined as a disease that by virtue of transmission or morbidity or mortality commands attention as a major threat to the health of the community.

The committee’s reliance on the 1998 interpretation of disease elimination is made in consideration of the epidemiological and clinical presentation of hepatitis B and C, and in an effort to balance the momentum for disease elimination against the real limitations of surveillance and treatment of these infections. The flexible target, already clear in the WHO plan, is more suitable to this question than a hard target of zero incidence or prevalence. For reasons discussed later in this report, hepatitis B patients can expect to live long lives with chronic infection and die of unrelated causes; ending deaths from hepatitis C could be managed far more easily than completely ending transmission of the virus. Disease elimination, or in this case elimination of the public health problem, is still a powerful motivator and one that can be embraced without overpromising or setting the program up for failure.

The committee appreciates the simplicity and motivational value of a zero-target elimination program. Barring major unforeseen scientific advances in treatment or prevention in both the United States and the world’s HBV- and HCV-endemic countries, such a hard goal does not seem feasible. The point at which hepatitis B and C are no longer public health problems might be somewhat open to interpretation. Not every state health officer or politician will have the same view of what constitutes a public health problem, but identifying cut points for such a determination is outside the scope of this report. In any case, to understand when a disease ceases to be a public health problem depends entirely on knowing the disease burden in the population. Monitoring any progress toward the elimination of hepatitis B and C will depend on better systems for surveillance.

Strategies for Hepatitis B and C Surveillance

Disease surveillance systems provide essential intelligence on the magnitude and distribution of a disease. Such data informs strategies for prevention and allocation of treatment resources. A functional disease surveillance system allows health departments to estimate the burden of disease, where and who it strikes, and to describe its natural history. Surveillance systems can monitor for the evolution of mutations or changes in virulence, identify outbreaks, evaluate prevention and control programs, and identify future research priorities (Thacker, 2000).

When surveillance systems are strong, potential outbreaks can be averted. Poor disease surveillance, in contrast, can cause public health disasters such as the 2014 Ebola outbreak and the reemergence of polio in parts of Africa (Hagan et al., 2015). Surveillance failures happen in rich countries too. In January 2015 state health officers identified an outbreak of HIV in rural Indiana (Conrad et al., 2015). Injection drug use drove the outbreak, and 84.4 percent of cases were found to be co-infected with HCV (Conrad et al., 2015). It is possible that better attention to hepatitis C surveillance might have helped identify this outbreak earlier. Reporting new cases of viral hepatitis, or any infectious disease, to the state or local health department allows for an accurate understanding of disease burden, eases case management, contributes to a better understanding of the disease’s transmission routes, and helps to identify outbreaks and monitor progress toward public health goals (Kirkey et al., 2013; Thacker, 2000).

Viral hepatitis is not a well-funded target for public health surveillance (CDC, 2013). Only seven jurisdictions in the United States (five states and two cities) have CDC funding for viral hepatitis surveillance (CDC, 2015c). The CDC and Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists set national guidelines on classifying and reporting acute and chronic infections, but state and local health departments are responsible for implementing these guidelines in the field and for feeding information to the national surveillance network (Church et al., 2014). Not all jurisdictions require reporting of chronic HBV or HCV infection, and when they do the reporting format is not standardized so valuable data are often missing (Church et al., 2014). Some health departments use automated, web-based systems, but such systems are expensive to buy and to maintain. Even when different jurisdictions use the same system, the configuration is adapted to local reporting policies. The CDC’s standardized reporting system is a good base program, available across the country, but it does not allow for more advanced surveillance practice.

Underreporting is common in cases of viral hepatitis, in part because the diseases affect people who may be out of contact with the health system: people born abroad, racial and ethnic minorities, people who inject drugs

or have been in prison. The building, global momentum for elimination of hepatitis B and C is cause enough to revisit the barriers.

Without better understanding of the burden of viral hepatitis, it will not be possible to make efficient use of the resources available to fight it. Expanded sentinel surveillance in high-risk clinical practices would give better understanding of current trends. Technology can also complement surveillance data. Geospatial imaging and mining of electronic health data has potential for disease surveillance, especially in hard-to-reach populations.

Key Findings and Conclusions

- Viral hepatitis is the seventh leading cause of death in the world. Hepatitis B and C cause the majority these deaths. The two diseases account for over a million deaths a year, about 20,000 of which are in the United States.

- Hepatitis B and C infections are asymptomatic until the later stages. About two-thirds and half of people infected with hepatitis B and C respectively do not know of their condition.

- Both infections are borne disproportionately by racial and ethnic minorities and by socially marginalized groups such as people who inject drugs.

- HBV vaccine conveys 95 percent immunity in three doses. New HCV treatments can cure 95 percent of infections. Taken together, these developments have encouraged international momentum for action against viral hepatitis.

- The elimination of hepatitis B and C poses challenges, both in defining what qualifies as elimination and in monitoring progress toward that goal.

- It is feasible in the relatively short term to control hepatitis B and C—meaning to reduce their incidence and prevalence.

- Eliminating the public health problem of hepatitis B and C—meaning that the diseases may remain but transmission will stop and the most undesirable manifestations prevented completely—is also feasible, but considerable barriers face any elimination program.

REFERENCES

Andrus, J. K., C. A. de Quadros, C. C. Solorzano, M. R. Periago, and D. A. Henderson. 2011. Measles and rubella eradication in the americas. Vaccine 29(Suppl 4):D91-D96.

The Carter Center. 2016a. Guinea worm disease: Worldwide case totals. http://www.cartercenter.org/health/guinea_worm/case-totals.html (accessed February 16, 2016).

The Carter Center. 2016b. International task force for disease eradication. http://www.cartercenter.org/health/itfde/index.html (accessed January 20, 2016).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 1992. Update: International task force for disease eradication, 1990 and 1991. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report CDC Surveillance Summaries 41(03):40-42.

CDC. 1993. Recommendations of the international task force for disease eradication. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report CDC Surveillance Summaries 42(16):i-38.

CDC. 2011. Hepatitis C virus infection among adolescents and young adults: Massachusetts, 2002-2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60(17):537.

CDC. 2013. Viral hepatitis surveillance: United States, 2013. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

CDC. 2015a. Hepatitis B FAQs for health professionals. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/hbvfaq.htm#overview (accessed January 14, 2016).

CDC. 2015b. Statistics and surveillance. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics (accessed March 14, 2016).

CDC. 2015c. Surveillance for viral hepatitis—United States, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2013surveillance (accessed February, 8, 2016).

CDC. 2015d. Vaccination coverage among adults, excluding influenza vaccination—United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report CDC Surveillance Summaries 64(04):95-102.

CDC. 2015e. Viral hepatitis. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/abc/index.htm (accessed January 14, 2016).

CDC. 2016. Hepatitis C FAQs for health professionals. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm#section1 (accessed January 14, 2016).

Chen, D. S. 2010. Toward elimination and eradication of hepatitis B. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 25(1):19-25.

Church, D. R., G. A. Haney, M. Klevens, and A. DeMaria, Jr. 2014. Surveillance of viral hepatitis infections. In Concepts and methods in infectious disease surveillance, edited by N. M. M’ikanatha and J. K. Iskander. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Cohen, C., S. D. Holmberg, B. J. McMahon, J. M. Block, C. L. Brosgart, R. G. Gish, W. T. London, and T. M. Block. 2011. Is chronic hepatitis B being undertreated in the United States? Journal of Viral Hepatitis 18(6):377-383.

Conrad, C., H. M. Bradley, D. Broz, S. Buddha, E. L. Chapman, R. R. Galang, D. Hillman, J. Hon, K. W. Hoover, M. R. Patel, A. Perez, P. J. Peters, P. Pontones, J. C. Roseberry, M. Sandoval, J. Shields, J. Walthall, D. Waterhouse, P. J. Weidle, H. Wu, and J. M. Duwve. 2015. Community outbreak of HIV infection linked to injection drug use of oxymorphone—Indiana, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report CDC Surveillance Summaries 64(16):443-444.

Cooke, G., M. Lemoine, M. Thursz, C. Gore, T. Swan, A. Kamarulzaman, P. DuCros, and N. Ford. 2013. Viral hepatitis and the global burden of disease: A need to regroup. Journal of Viral Hepatitis 20(9):600-601.

Dowdle, W. R. 1998. The principles of disease elimination and eradication. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 76(Suppl 2):22.

El-Serag, H. B., and F. Kanwal. 2014. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: Where are we? Where do we go? Hepatology 60(5):1767-1775.

FDA (Food and Drug Administration). 2013. Guidance for industry: Chronic hepatitis C virus infection: Developing direct-acting antiviral drugs for treatment. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

Feld, J. J., I. M. Jacobson, C. Hézode, T. Asselah, P. J. Ruane, N. Gruener, A. Abergel, A. Mangia, C.-L. Lai, H. L. Y. Chan, F. Mazzotta, C. Moreno, E. Yoshida, S. D. Shafran, W. J. Towner, T. T. Tran, J. McNally, A. Osinusi, E. Svarovskaia, Y. Zhu, D. M. Brainard, J. G. McHutchison, K. Agarwal, and S. Zeuzem. 2015. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 infection. New England Journal of Medicine 373(27):2599-2607.

Foster, G. R., N. Afdhal, S. K. Roberts, N. Bräu, E. J. Gane, S. Pianko, E. Lawitz, A. Thompson, M. L. Shiffman, C. Cooper, W. J. Towner, B. Conway, P. Ruane, M. Bourlière, T. Asselah, T. Berg, S. Zeuzem, W. Rosenberg, K. Agarwal, C. A. M. Stedman, H. Mo, H. Dvory-Sobol, L. Han, J. Wang, J. McNally, A. Osinusi, D. M. Brainard, J. G. McHutchison, F. Mazzotta, T. T. Tran, S. C. Gordon, K. Patel, N. Reau, A. Mangia, and M. Sulkowski. 2015. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for HCV genotype 2 and 3 infection. New England Journal of Medicine 373(27):2608-2617.

Hagan, J. E., S. G. F. Wassilak, A. S. Craig, R. H. Tangermann, O. M. Diop, C. C. Burns, and A. Quddus. 2015. Progress toward polio eradication—worldwide, 2014-2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report CDC Surveillance Summaries 64(19):527-531.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2014. Action plan for the prevention, care, & treatment of viral hepatitis. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

Hoeffel, E. M., S. Rastogi, M. O. Kim, and H. Shahid. 2012. The Asian population: 2010. Washington, DC: Department of Commerce.

Hopkins, D. R. 2009. The allure of eradication. Global Health 1(3):14-16.

IHME (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation). 2015. GBD compare. http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-mortality (accessed February 23, 2016).

IHME. 2016. Global burden of disease study 2013 (GBD 2013) data downloads—full results. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/global-burden-disease-study-2013-gbd-2013-data-downloads-full-results (accessed March 14, 2016).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2010. Hepatitis and liver cancer: A national stragey for prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kirkey, K., K. MacMaster, A. Suryaprasad, F. Xu, M. Klevens, H. Roberts, A. Moorman, S. Holmberg, and J. Webeck. 2013. Completeness of reporting of chronic hepatitis B and C virus infections—Michigan, 1995-2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report CDC Surveillance Summaries 62(06):99-102.

Lai, C.-L., and M.-F. Yuen. 2013. Prevention of hepatitis B virus–related hepatocellular carcinoma with antiviral therapy. Hepatology 57(1):399-408.

Lee, M.-H., H.-I. Yang, S.-N. Lu, C.-L. Jen, S.-L. You, L.-Y. Wang, C.-H. Wang, W. J. Chen, and C.-J. Chen. 2012. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection increases mortality from hepatic and extrahepatic diseases: A community-based long-term prospective study. Journal of Infectious Diseases 206(4):469-477.

Lin, S. Y., E. T. Chang, and S. K. So. 2007. Why we should routinely screen Asian American adults for hepatitis B: A cross-sectional study of Asians in California. Hepatology 46(4):1034-1040.

Luu, L. 2015. Liver transplants. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/776313-overview (accessed January 14, 2016).

Mitchell, T., G. L. Armstrong, D. J. Hu, A. Wasley, and J. A. Painter. 2011. The increasing burden of imported chronic hepatitis B—United States, 1974-2008. PLoS ONE 6(12):e27717.

Mitruka, K., T. Tsertsvadze, M. Butsashvili, A. Gamkrelidze, P. Sabelashvili, E. Adamia, M. Chokheli, J. Drobeniuc, L. Hagan, A. M. Harris, T. Jiqia, A. Kasradze, S. Ko, V. Qerashvili, L. Sharvadze, I. Tskhomelidze, V. Kvaratskhelia, J. Morgan, J. W. Ward, and F. Averhoff. 2015. Launch of a nationwide hepatitis C elimination program—Georgia, April 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report CDC Surveillance Summaries 64(28):753-757.

Mohd Hanafiah, K., J. Groeger, A. D. Flaxman, and S. T. Wiersma. 2013. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: New estimates of age specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology 57(4):1333-1342.

Ott, J., G. Stevens, J. Groeger, and S. Wiersma. 2012. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: New estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine 30(12):2212-2219.

Thacker, S. M. 2000. Historical development. In Principles and practice of public health surveillance, edited by L. M. Lee, S. M. Teutsch, S. B. Thacker, and M. E. St. Louis. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Tulchinsky, T. H., and E. Varavikova. 2009. The new public health. Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA: Elsevier/Academic Press.

United Nations. 2014 August 12. Open working group proposal for sustainable development goals. Paper presented at United Nations General Assembly, New York.

U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. 2016. United States cancer statistics: 1999-2012. http://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/map/map.withimage.php?00&001&035&00&0&01&0 &1&5&0#results (accessed January 15, 2016).

Volk, M. L., R. Tocco, S. Saini, and A. S. F. Lok. 2009. Public health impact of antiviral therapy for hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology 50(6):1750-1755.

WHO (World Health Organization). 2010. Disease eradication in the context of global health in the 21st century. Paper read at Ernst Strungmann Forum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, August 29-September 3, 2010.

WHO. 2016a (unpublished). The case for investing in the elimination of hepatitis B and C as public health problems by 2030.

WHO. 2016b. Hepatitis: Frequently asked questions. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/hepatitis/world_hepatitis_day/question_answer/en/ (accessed January 14, 2016).

World Health Assembly. 2014. Hepatitis. Paper read at 67th World Health Assembly, May 24, Geneva, Switzerland.

Zibbell, J. E. 2015. Hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs in the United States. https://www.aids.gov/pdf/hcv_in_pwid_webinar.pdf (accessed February 17, 2016).

This page intentionally left blank.