3

Modifiable Risk and

Protective Factors Associated with

Overweight and Obesity Through Age 5

The second panel of the workshop included five presentations that progressed through the maternal–child life course to explore modifiable risk and protective factors for obesity. The first looked at pregnancy; the

second at breastfeeding; the third at complementary feeding; the fourth at responsive feeding; and the fifth at sleep, activity, and sedentary behavior. Together, these presentations described a wide range of opportunities for countering obesity in the first 5 years of life.

PREGNANCY FACTORS IN RELATION TO CHILDHOOD OBESITY

Lisa Bodnar, associate professor in the Departments of Epidemiology and Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health and School of Medicine, took as her point of departure the idea that, as pointed out in the previous chapter, pregnancy is an especially powerful opportunity for the promotion of healthy eating and physical activity behaviors among women (Phelan, 2010). Pregnant women are highly motivated to improve their health and the health of their infants, and this is a period of their lives when they are particularly likely to adopt new behaviors (Phelan, 2010). Pregnant women also have frequent contact with their health care providers. According to Bodnar, all of these features of pregnancy offer opportunities for intervention.

Bodnar discussed four factors that have a potentially causal relationship with childhood obesity: maternal prepregnancy body mass index (BMI), weight gain in pregnancy, gestational diabetes, and smoking in pregnancy.

Bodnar cited a study of approximately 8,500 low-income families in Ohio in which birth certificate data were linked to measured weights and heights obtained through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) at 2, 3, and 4 years of age (Whitaker, 2004). The result was what she called an “elegant dose–response relationship” between a mother’s prepregnancy BMI and the likelihood that her child would be obese at these ages. The children of mothers who were obese or severely obese before they became pregnant had a three- to fourfold increased risk of obesity. A number of subsequent studies have demonstrated this relationship, Bodnar noted. A meta-analysis by Yu and colleagues (2013) compared underweight, overweight, and obese women with normal-weight women and found that the children of overweight and obese women have about a twofold increased risk of becoming overweight or obese later in life.

The pathways through which maternal obesity may contribute to childhood obesity are complex, said Bodnar, involving both the metabolic programming of risk and the sharing of genes and behaviors. “We haven’t really been able to tease apart which is more important,” she said. “It is likely that they all play a role.”

Bodnar also pointed out that prepregnancy BMI is difficult to modify because nearly half of pregnancies are unplanned or mistimed (Finer and Zolna, 2011), and most women who are planning a pregnancy do not seek

preconception care (Robbins et al., 2014). “Seeking preconception care may not even be on their radar,” she said. Also, she noted, few women who are obese know that their weight can have immediate consequences for their children (Nitert et al., 2011).

After conception, Bodnar continued, the focus of research turns toward influences that occur during pregnancy, one of which is the amount of weight a woman gains during gestation. In 2009 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the National Research Council (NRC) published modified gestational weight gain recommendations that incorporate prepregnancy BMI (IOM and NRC, 2009). The recommended weight gain for a normal-weight woman is 25 to 35 pounds, whereas that for an obese woman is 11 to 20 pounds. Any gain above these upper ranges is generally considered excessive, Bodnar said.

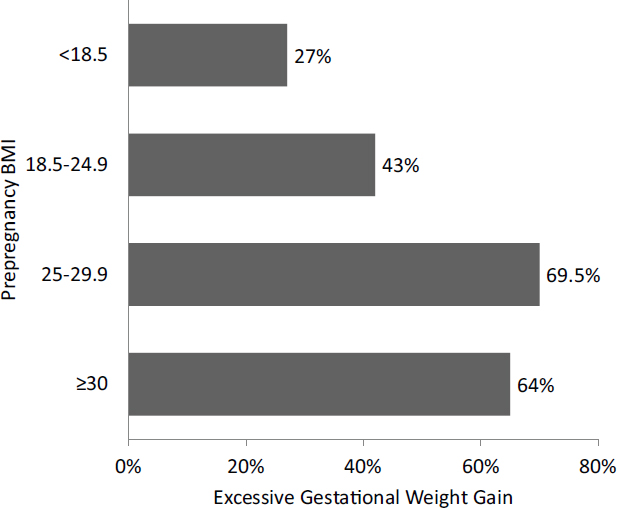

Excessive gestational weight gain is common among U.S. women, Bodnar observed. Even among normal-weight women, 43 percent gain too much weight during their pregnancies (Truong et al., 2015) (see Figure 3-1). Among overweight and obese women, 65 to 70 percent exceed the IOM and NRC recommendations for weight gain during their pregnancies (Truong et al., 2015), Bodnar noted. When Oken and colleagues (2007) followed about 1,000 mother–child pairs for 3 years, they found positive relationships between total pregnancy weight gain and the children’s BMI z-scores, triceps skinfold thicknesses, and systolic blood pressure at age 3 years.

Bodnar cited a meta-analysis of 12 different studies by Mamun and colleagues (2014), which found that children born to mothers who gained more than the recommended amount of weight during pregnancy had a 40 percent increased risk of developing obesity in their lifetime. The magnitude of this risk varied over time: children less than 5 years of age had about a 90 percent increase in the risk of childhood obesity when their mothers gained too much weight during pregnancy, while children aged 5-18 also showed this association, although it was less strong (only about a 30 percent increase in risk), and for adults (older than 18), the increase in risk was 47 percent.

Weight gain during pregnancy entails a unique balancing act, Bodnar noted. Women who gain too little weight during pregnancy have an increased risk of preterm birth and of having babies who are small for gestational age (IOM and NRC, 2009), she said, while those who gain too much weight have an increased risk of their children being obese (Mamun et al., 2014).

Another consideration, Bodnar noted, is that women who gain too much weight during pregnancy have a tendency to retain that weight postpartum (Viswanathan et al., 2008). If they have subsequent pregnancies, these women are more likely to start pregnancy overweight, which further increases their risk of gaining too much weight during pregnancy (IOM and NRC, 2009; Pérez-Escamilla and Kac, 2013). With each successive

SOURCES: Presented by Lisa Bodnar on October 6, 2015 (adapted and reprinted with permission from Truong et al., 2015).

pregnancy, the likelihood of this obesity cycle increases (Pérez-Escamilla and Kac, 2013).

Interventions to reduce gestational weight gain have shown mixed results, Bodnar reported. A recent meta-analysis reviewed 49 randomized controlled trials involving more than 11,000 pregnant women who engaged in interventions that included dieting, exercise, or some combination of the two (Muktabhant et al., 2015). Bodnar noted that these interventions reduced the risk of excessive weight gain during pregnancy by about 20 percent, but the effect on the risk of macrosomia (excessive birth weight for length of gestation) in the women’s babies was smaller and not statistically significant, although the effect was stronger for women who were overweight, obese, or at risk of gestational diabetes. No studies have yet looked at the effects of interventions on childhood obesity, and “this is an important gap that needs to be addressed,” Bodnar said.

Turning to the third factor introduced at the beginning of her presentation, Bodnar observed that gestational diabetes is related to fetal overnutrition, which may influence obesity in children (Catalano and Hauguel-de Mouzon, 2011). Mothers with gestational diabetes are more likely to have children with higher birth weights and greater fetal adiposity, although this relationship is significantly diminished when maternal prepregnancy BMI is accounted for (Kim et al., 2012). Bodnar noted that nearly half of gestational diabetes cases are thought to be attributable to overweight and obesity, and the incidence of gestational diabetes is strongly associated with prepregnancy BMI (Kim et al., 2010).

Bodnar cited a meta-analysis by Philipps and colleagues (2011) that found that mothers with all types of gestational diabetes (onset both before and during pregnancy) had children with higher BMI z-scores. When these results were adjusted for prepregnancy BMI, she noted, the association was significantly attenuated. Another meta-review (Kim et al., 2012) resulted in similar conclusions, although the sample sizes of individual studies have tended to be small, and few have used direct measures of adiposity in children. Maternal BMI appears to be a stronger factor than gestational diabetes in childhood obesity, Bodnar said, but “there is still work to be done in this area.”

Moving to a fourth factor with a potentially causal relationship with childhood obesity, Bodnar stated that smoking in pregnancy is consistently associated with an increased risk of childhood obesity (Ino, 2010; Oken et al., 2008). She observed that there are two mechanisms thought to explain this association. The first is that children born to smoking mothers may experience a period of postnatal catch-up growth, following their slower growth in utero (Ong, 2006). The second is that maternal smoking may affect appetite regulation, food preferences, or nutrient metabolism in offspring (Ayres et al., 2011; Behl et al., 2013; Ino, 2010). Bodnar reported that Oken and colleagues (2008) summarized 14 studies of maternal smoking in children aged 3 to 33 years and found a 50 percent increase in the risk of childhood obesity among the children of mothers who smoked during their pregnancies, after adjusting for maternal BMI and other factors. Ino (2010) found similar results.

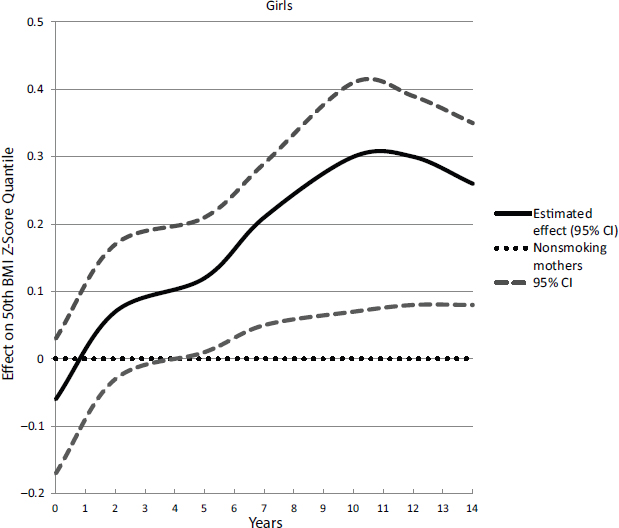

Bodnar highlighted a longitudinal study by Riedel and colleagues (2014) that followed about 1,000 children, some exposed to smoking in utero and some not, to see how their relative weights changed over time. The researchers found that, among girls born to smoking mothers, overall BMI z-scores were lower at birth compared with babies born to nonsmokers, but by 4 and 5 years of age, their BMI z-scores were higher than those of their unexposed peers (see Figure 3-2). Bodnar noted that related research has found that exposure to secondhand smoke during pregnancy increases the risk for childhood obesity (Griffiths et al., 2010; Raum et al., 2011).

NOTE: CI = confidence interval.

SOURCES: Presented by Lisa Bodnar on October 6, 2015 (reproduced with permission from Riedel et al., 2014).

Many important knowledge gaps exist in the understanding of maternal influences on childhood obesity operating during pregnancy, said Bodnar. She cited the need for specific markers, such as maternal body composition, fat distribution, diet, and metabolic changes in pregnancy. Another major question, she suggested, is how early-life nutrition and physical activity, as well as exposure to chemicals during pregnancy, may modify the long-term risk of obesity (Heindel and vom Saal, 2009; Symonds et al., 2013).

BREASTFEEDING AND THE RISK OF CHILDHOOD OBESITY

Breastfeeding may protect against childhood obesity for several possible reasons, observed Rafael Pérez-Escamilla, professor of epidemiology,

Yale School of Public Health. Breastfed babies may be better able to self-regulate their energy intake using cues related to changes in milk composition during feeding, he said, and mothers using formula may be more likely to overfeed their babies because they have more control over that process than is the case when a baby self-regulates intake (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 1995). He noted that breast milk has a lower protein content than infant formula, which may protect against higher insulin levels and greater obesity risk (Koletzko et al., 2009). Echoing a point made earlier by Mennella, moreover, he observed that, depending on maternal diet, breastfed babies are exposed to a greater diversity of flavors, which may positively affect their taste preferences for fruits, vegetables, and other foods lower in energy density if their mothers consume those foods (Mennella, 2014). Finally, he said, suboptimal infant feeding patterns using formula may lead to excessive weight gain during infancy, which is likely to increase the risk of childhood obesity (Dewey, 1998; Pérez-Escamilla and Kac, 2013).

Pérez-Escamilla reported on two recent meta-analyses assessing the epidemiological evidence behind the hypothesis that breastfeeding offers protection against the development of childhood obesity. In a meta-analysis of 105 studies, Horta and colleagues (2015) found a significant reduction—26 percent—in the odds of children becoming obese later in life if they were breastfed as infants. This systematic review covered evidence from low-, middle-, and high-income countries and did not impose restrictions on the experimental or observational designs allowed, and the studies varied widely on such attributes as breastfeeding modalities and comparison groups. The range of ages at which obesity was assessed was 1 to more than 20 years, with the effect varying by age. Also, the larger the sample size included in the study, the lower was the effect size detected, and there were differences between children born before and after 1980, perhaps related to differences in formula composition, contended Pérez-Escamilla. Cohort studies tended to show the smallest effect size (odds ratio [OR] = 0.79) relative to case-control (OR = 0.68) and cross-sectional studies (OR = 0.67), he noted. In addition, the greater the adjustment for confounding, the smaller was the effect size. Effect sizes were almost identical across high- and middle- to low-income countries, Pérez-Escamilla reported, and exclusive breastfeeding tended to produce the strongest protection. Looking only at the studies of the highest possible quality, the review found an effect size of just 13 percent reduction in risk.

In the second meta-analysis, Giugliani and colleagues (2015) looked at 35 studies, but only 12 of them reported BMI or weight-for-length (or -height). Of these, 10 were randomized controlled trials, and two were quasi-experimental. The studies covered high-, middle-, and low-income countries and a wide variety of interventions and ages. Although the evidence from these studies must be interpreted with caution, Pérez-

Escamilla said, the benefits appeared to be somewhat higher in high-income versus lower-income countries. Smaller sample sizes also tended to yield greater effects, he observed. The authors did find a modest reduction in the risk of childhood obesity as a function of maternal exposure to a breastfeeding promotion program in low- and middle-income countries. Pérez-Escamilla noted that although the effect size was small—a reduction of just 0.06 z-score mean difference in BMI or weight-for-length (or height)—it is statistically significant.

Beyerlein and von Kries (2011) found that only among children in the highest BMI percentiles was breastfeeding associated with a lower BMI compared with formula feeding, suggesting that children with a greater propensity for obesity may benefit the most from breastfeeding, contended Pérez-Escamilla. Subsequent studies (e.g., Dedoussis et al., 2011), he noted, have found that particular alleles in the fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene may help explain why breastfeeding protection is stronger among babies with a genetic propensity to become obese. This genetic predisposition may indeed be impacted by breastfeeding, he suggested. Abarin and colleagues (2012) found that, among boys with the FTO gene propensity for obesity, there was a dose–response relationship between how long they received only breast milk and the degree of protection against childhood obesity they received by 14 years of age. Among the boys who had this genomic propensity, Pérez-Escamilla said, none were overweight if they had received only breast milk for 5 months, compared with half of the boys who received only breast milk for less than 2 months.

Pérez-Escamilla made several recommendations for additional research. He pointed to the need for prospective studies that would carefully measure the duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Genomic propensities are a promising area for future epidemiological and basic mechanistic research, he contended, along with the effects of breastfeeding as a function of other maternal–child life-course factors, including prepregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, and the timing of the introduction and the type of complementary feeding (Daniels et al., 2015a; Pérez-Escamilla and Bermúdez, 2012). He also noted that researchers generally do not correct for the effects of diet and physical activity between the period of breastfeeding and the time of anthropometric measurement, which he characterized as a “huge gap that needs to be filled.”

In conclusion, said Pérez-Escamilla, breastfeeding is associated with prevention of childhood obesity in the general population, with a stronger association among children with a genomic propensity to become obese. The effect size is small, but this is not surprising, he suggested, given the constellation of factors that influence obesity. “Breastfeeding protection, promotion, and support should form a part of childhood obesity prevention strategies,” he asserted. “Thankfully, we have a fair number of

evidence-based strategies that work at both the facility and the community level, and some that work at the macro-environment [level], protecting the ability of moms who wish to breastfeed their babies.” These include the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (Pérez-Escamilla, 2007), peer counseling (Chapman et al., 2010), and breastfeeding protection policies (Hawkins et al., 2013; Smith-Gagen et al., 2014).

COMPLEMENTARY FEEDING

Gestation and the first 2 years of life shape metabolic, immunologic, sensory, behavioral, developmental, and growth parameters for the rest of a person’s life, observed Jose Saavedra, global chief medical officer, Nestlé Nutrition, and associate professor of pediatrics, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. He described the work of Dattilo and colleagues (2012), who sought to identify comprehensively those actionable, modifiable factors associated with overweight during this critical period. Modifiable factors were defined as feeding and related dietary, environmental, or behavioral practices that could potentially be modified by parents and caregivers, with interventions beginning at birth.

Surprisingly, the factors that are significantly subject to the direct influence of parents and caregivers, and have been associated with childhood obesity in the first 2 years of life are not numerous, Saavedra pointed out. Those related to food and diet include

- lack of breastfeeding,

- early introduction (before 4 months of age) of complementary foods,

- high intake of sweetened beverages, and

- low intake of fruits and vegetables.

Those related to feeding and behaviors include

- lack of breastfeeding;

- lack of responsive feeding practices by caregivers, including low attention to hunger and satiety cues and the use of overly restrictive, controlling, rewarding, or pressure feeding;

- low total and nocturnal sleep;

- lack of family meals;

- television/screen viewing time; and

- low active play.

Saavedra focused on the modifiable factors related to complementary feeding. Two large studies in the United States have looked at infant feed-

ing and care practices in the first year of life, he reported. One was the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPS II), a longitudinal assessment conducted using food frequency questionnaires delivered by mail from 2005 to 2007 to examine infant feeding and feeding transitions during the first year of life (CDC, 2015c). The study started with a group of about 4,000 pregnant women and followed about 2,000 of them and their infants until they reached 12 months of age, with higher-risk groups underrepresented. The second large study was the Nestlé Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study (FITS), conducted in 2002 and 2008, which included nationally representative samples aged 0-4 years. Diet was assessed cross-sectionally in households using a 24-hour dietary recall survey carried out by phone (Nestlé, 2014). The IFPS II found extremely dynamic feeding patterns in the first few months of life, Saaverda said (Grummer-Strawn et al., 2008). The period between the end of 3 months of age and the beginning of 5 months of age, in particular, is extremely dynamic, he noted. At the beginning of this period, 20 percent of infants have already been exposed to complementary foods; by the end of the period, this figure rises to 40 percent (Fein et al., 2008; Grummer-Strom et al., 2008). The FITS reinforced the dynamic change in both the amount and the variety of solid foods introduced within a brief time period (Siega-Riz et al., 2010).

Drawing from these and other studies, Saavedra reported that the early introduction of solid foods, before age 4 months, is seen in children who are not initially breastfed; those who are not breastfed until 6 months of age; and those who are born of less educated, single, young mothers living in the eastern rather than the western United States and participating in WIC (Clayton et al., 2013; Fein et al., 2008; Grummer-Strawn et al., 2008). Drawing from IFPS II data (Clayton et al., 2013), Saavedra stated that the following reasons for the early introduction of solid food are most commonly cited:

- “My baby was old enough to begin to eat solid food.” (88.9 percent)

- “My baby seemed hungry a lot of the time.” (71.4 percent)

- “My baby wanted the food I ate or in other ways showed an interest in solid food.” (66.8 percent)

- “I wanted to feed my baby something in addition to breast milk or formula.” (64.8 percent)

- “It would help my baby sleep longer at night.” (46.4 percent)

- “A doctor or health care professional said my baby should begin eating solid food.” (55.5 percent).

Saavedra called particular attention to the final reason, related to inadequate advice from health care professionals. “We have some of ourselves to blame for the lack of understanding and poor education we provide with

regard to when complementary food introduction could or should be happening,” he asserted.

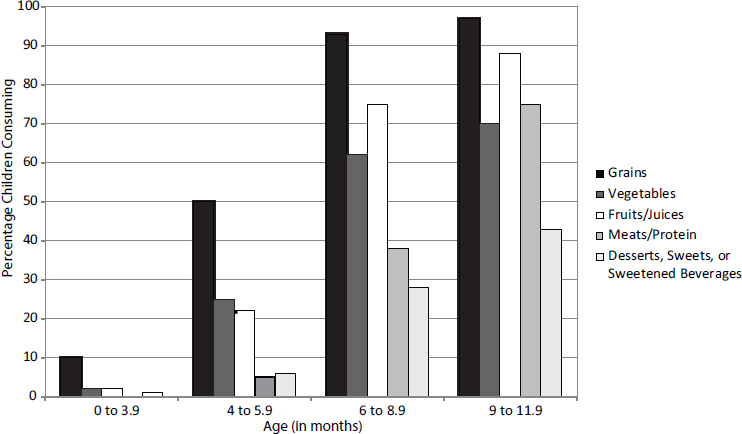

Grains tend to be the first food introduced, noted Saavedra, with the gradual addition of vegetables; fruits and juices; meats; and sweets, sweetened beverages, and desserts (Siega-Riz et al., 2010) (see Figure 3-3). He added that the results of the FITS show that average energy intake in North America is higher than estimated requirements throughout the first 4 years of life. Average protein intake also is considerably higher than estimated requirements. So, too, is the intake of saturated fat, Saavedra said, with about three-quarters of children in the third and fourth years of life exceeding dietary guidelines for this nutrient. Moreover, more than 80 percent of children exceed the upper limit for sodium by the fourth year of life. At the same time, virtually no children reach the current recommendation for fiber intake during this period (Butte et al., 2010). “We probably need to modify our expectations with regard to fiber intake targets, as they seem unreachable even with adequate food choices,” Saavedra suggested. He continued, “That said, fiber highly correlates with the energy density of the diets. The higher the fiber intake, particularly when fruits and vegetables are consumed as fruits and vegetables and not as extracts, juices, or beverages, the energy density of the diet significantly goes down, and the total energy intake by the child also goes down. Fiber intake may be important not for the purposes of meeting [the recommendation], per se, but for the

SOURCES: Presented by Jose Saavedra on October 6, 2015 (reprinted with permission, Siega-Riz et al., 2010).

purposes of decreasing the energy density [which] contributes to a lower energy intake.”

On any given day, once complementary feeding has been initiated, Saavedra reported, 30 to 40 percent of children aged 6 months and older do not eat a vegetable, and 20 to 35 percent of children in this age group do not eat a fruit (Fox et al., 2010; Siega-Riz et al., 2010). Yet after their first birthdays, 70 to 90 percent of children are fed some type of sweet, with sweetened beverages constituting about a quarter of this intake. More than a third of the calorie increase from ages 6 to 48 months is attributable to sweets and sweetened beverages, including candy, ice cream, sweet rolls, pie, cake, and cookies (Fox et al., 2010), which “could potentially explain a huge part of the problem,” said Saavedra. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages in infancy almost doubles the odds of consuming them at age 6, he noted (Pan et al., 2014). Also, by 4 years of age, the majority of toddlers eat at a fast food restaurant one to three times per week (Briefel et al., 2015). “Again, when you look at . . . the energy density, the nutrient density, and the density as it relates to saturated fat, we have, obviously, a problem,” Saavedra asserted. He reported data from the FITS that on average, less than 10 percent of the energy for a 4-year-old comes from fruits and vegetables. Finally, with respect to the portion of total calories contributed by each food group, he noted that the pattern is clearly set before 2 years of age. Despite changes in total energy consumption and a growing number of food options with age, the relative energy contribution of each food group remains the same, he said, suggesting that this pattern will remain unchanged for life.

Saavedra finished by saying, “The most important messages are [we] need to start educational interventions much earlier than what we have been paying attention to.” Echoing a point made in Mennella’s presentation (see Chapter 2), he went on to say that it is important to take advantage of the fact that a child’s first few months of life are the time when families are most receptive to education in adopting behaviors, particularly related to dietary patterns.

During the discussion period, Saavedra made an interesting point with regard to the food introduced to children during the first year of life. In North America relative to many other parts of the world, many more vegetables and fruits are commercially available for infants and children, and the majority of them no longer have added sugar and salt. However, the table food parents introduce to infants and toddlers tends to have much more added sugar and salt, Saavedra said, not only in the United States but elsewhere as well. Furthermore, these early food offerings can establish patterns of food intake that are difficult to change later in life.

Saavedra also suggested that parents need better education in bottle feeding. For example, infants receiving breast milk exclusively in a bottle may actually gain more weight than infants receiving formula in

a bottle. Compared with the natural maternal–child bidirectional feedback mechanisms of breastfeeding, bottle feeding can easily override infants’ satiety signals if parents are not familiar with or educated in their infants’ hunger and satiety cues.

Changing behaviors is difficult, Saavedra acknowledged, but again, the birth of a child is a receptive time for a mother to change her behaviors or induce a behavior in a child. The target messages are not numerous, and just a few could make a big difference, he asserted. They include breastfeeding, not introducing solids before 4 months of age, increasing the child’s consumption of fruits and vegetables, and decreasing the consumption of sweets and sweetened beverages. Saavedra ended by saying, “The key messages are not many, [and] education on these messages is feasible. And it can be made accessible and scalable, particularly if we make full use of current technology. If we work together, a good part of the solution is within our reach.”

RESPONSIVE PARENTING

For most of history, food scarcity was the context in which parenting behaviors developed, said Leann Birch, William P. Flatt professor, Department of Foods and Nutrition, University of Georgia. Food availability was unpredictable, food choice was limited, palatability was questionable, and energy and nutrient densities were low in the foods that were available. “There are still many people in the world who are living in this situation,” Birch noted.

Many of the traditional parenting practices that developed in this context, Birch said, are still the default options today. These practices include feeding in response to infant crying regardless of the reason, trying to get children to eat large portions, requiring that they finish what is on their plate, having them eat even when they say they are not hungry, and believing that a big baby is a healthy baby. The problem, said Birch, is that in the current obesogenic environment, these practices may place children at increased risk for rapid weight gain and obesity.

One potential way to change these traditional feeding practices is to use what is called responsive parenting, Birch asserted. A long-established concept in the developmental literature, she explained, responsive parenting entails prompt, developmentally appropriate responses that are contingent on a child’s behavior and needs. Mothers are encouraged to learn to recognize infant cues, whether their babies are hungry or distressed for some other reason, and then are taught alternative soothing strategies to use depending on the cues. For example, parents are encouraged to try minimal interventions first to see whether the baby will settle and go back to sleep. If the baby is still fussy, feeding is a reasonable response.

Responsive parenting is meant to foster the development of self-regulation and promote cognitive, social, and emotional development, Birch observed. “The infant begins to learn that the world is a predictable place in which their actions have an effect,” she said.

Birch posed the question of whether responsive parenting can affect rapid weight gain and obesity risk early in life. The existing evidence is intriguing, she said, but still scant. First, evidence from randomized controlled trials shows that responsive parenting is modifiable. For example, Landry and colleagues (2006) showed that a parenting intervention known as the Play and Learning Strategies1 increased mothers’ contingent responsiveness compared with a control group. Birch noted that responsive parenting also has been positively associated with cognitive, social, and emotional growth in children (Eshel et al., 2006), particularly the development of self-regulatory skills. She explained that self-regulation involves a number of overlapping constructs, including self-control, willpower, effortful control, delay of gratification, emotion regulation, executive function, and inhibitory control (Anzman-Frasca et al., 2015). Multiple aspects of self-regulation could be important in avoiding excessive intake in the current food environment, she stated.

Birch and her colleagues have been studying whether responsive parenting can reduce obesity risk (Paul et al., 2011, 2014; Savage et al., 2015). In a randomized controlled trial known as SLIMTIME (SLeeping and Intake Methods Taught to Infants and Mothers Early in Life Trial), they followed 160 first-time mothers and infants to see whether responsive parenting can affect the primary outcome of infant weight gain and such secondary outcomes as sleep duration, night feedings, and the use of feeding to soothe. The study had a two-by-two intervention design. The three intervention groups received either a soothe or sleep intervention in which mothers were taught to discriminate between hunger and other sources of infant distress and to use soothing strategies in response to fussiness, particularly at night; a feeding intervention in which mothers were instructed to delay complementary foods until 4 months, avoid putting infant cereal into bottles, and pay attention to hunger and satiety cues; or both. A fourth group did not receive either intervention.

One observation, Birch reported, was that mothers in the SLIMTIME intervention groups were less likely than those in the control group to report encouraging their infants to finish the bottle, although even in the intervention groups, half the mothers were still doing so. The researchers also saw differences in early emotion regulation, which emerges around the end of the first year of life. Compared with the control group, the responsive parenting infants were better able to regulate their negative emotions

___________________

1 See https://www.childrenslearninginstitute.org/programs/play-and-learning-strategies-pals (accessed April 20, 2016).

to recover from being upset, fussing, and crying during a toy removal task (Anzman-Frasca et al., 2013). Babies in the intervention groups also were fed less in the middle of the night and were sleeping a bit longer than those in the control group (Paul et al., 2011). “They are learning to self-soothe, to calm themselves down, to settle, and not elicit the parent to give them a feeding,” said Birch.

The SLIMTIME trial produced differences in weight-for-length percentiles at 1 year, when the intervention ended (Paul et al., 2011), with the greatest effects being among children who received the intervention focused both on the introduction of solids into the diet and on soothing and sleeping. “It took both of those things to move the needle on weight-for-length percentiles at 1 year,” said Birch.

Birch described an ongoing trial known as INSIGHT (Intervention Nurses Starting Infants Growing on Healthy Trajectories), in which the responsive parenting intervention has been expanded to include helping babies sleep longer, dealing with fussy babies, interacting with babies when they are awake and alert, and other parenting practices (Paul et al., 2014). According to preliminary data from this trial, she said, on average (based on a Kolmogorov Smirnov two-sample test, p < 0.01), infants in the parenting intervention have less rapid weight gain from birth to 28 weeks and have lower weight-for-length percentiles at 1 year of age (Savage et al., 2015). Based on these results, “responsive parenting can make a noticeable difference in early rapid weight gain,” Birch asserted, although “whether we will have longer-term effects still remains to be seen.”

Many questions still surround this work, Birch noted. Does responsive parenting have collateral benefits for other aspects of child development? Are the results generalizable to higher-risk samples? Can designs be more resource-efficient and effective? Does the dose, timing, or mode of intervention delivery have powerful effects? What are the long-term effects?

In both the SLIMTIME and INSIGHT trials, Birch explained, the interventions were delivered very early in life by research nurses, an expensive approach that is unlikely to be scalable. Also, she noted, the trials involved first-time parents, who may be more open to new behaviors than mothers who already have children. In response to a question, she responded that her study has gathered data on the mothers’ employment and use of day care, as well as on their weights and diets, but these data have not yet been analyzed.

SLEEP, ACTIVITY, AND SEDENTARY BEHAVIOR

“There was never a child so lovely . . . but his mother was glad to get him to sleep.”

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Despite Emerson’s timeless description of the pleasures of an infant sleeping, the rising prevalence of childhood obesity has been paralleled by secular trends of shorter sleep durations in children, observed Elsie Taveras, division chief of general academic pediatrics and director of pediatric population health management, Massachusetts General Hospital for Children; associate professor of pediatrics and population medicine, Harvard Medical School; and associate professor of nutrition, Harvard School of Public Health. She cited a meta-analysis of almost 700,000 children from 20 countries, encompassing more than 100 years of data, in which Matricciani and colleagues (2012) found that, on average, children today sleep about 20-25 minutes less each day than their parents did when they were the same age. Across childhood, she noted, evidence suggests a decrease in sleep duration over the past 20 years, due in part to later bedtimes (Dollman et al., 2007; Iglowstein et al., 2003). “As some of us who are on call and leave the hospital late at night can attest to, there are very young children who are awake way too late at night,” said Taveras. Similar secular trends of insufficient sleep are occurring among adults, she noted.

Taveras observed that infants and toddlers in the lowest quartile of sleep are more likely to be put to bed asleep versus drowsy or awake (National Sleep Foundation, 2004). As was also noted by Birch, these children may not be learning to self-regulate their own sleep as effectively as others. Older children in the lower quartile of sleep are more likely to share a room or bed, are more likely to drink one or more caffeinated beverages during the day, and are more likely to have a television in the room where they sleep (National Sleep Foundation, 2004).

Evidence from the adult literature has shown a strong correlation between obesity in the United States and the increasing prevalence of adults who report insufficient sleep, said Taveras. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the same states that have the highest prevalence of obesity2 also have the highest prevalence of adults who perceive themselves as sleeping too little,3 and the pooled odds ratio for short sleep duration and obesity in adults is 1.55 (Cappuccio et al., 2008). Furthermore, Taveras noted, insufficient sleep duration in adults is associated with many adverse health conditions, including cancer, obesity, diabetes, and coronary heart disease, as well as all-cause mortality and lower life expectancy (Ayas et al., 2003; Gangwisch et al., 2006; King et al., 2008; Kripke et al., 2002; Patel and Hu, 2008; Patel et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2007).

___________________

2 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2014 data: www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalencemaps.html (accessed April 20, 2016).

3 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2008 data: www.cdc.gov/sleep/data_statistics.html (accessed April 20, 2016).

Taveras reported that a systematic review of 29 studies by Hart and colleagues (2011) suggested that both short sleep and later bedtimes in infants and children were associated with an increased risk for becoming or being overweight or obese. Some debate still surrounds this issue, she noted. Some studies have found an inverse association between sleep duration and adiposity in infancy, others have had null findings, and at least one randomized controlled trial of an infant sleep intervention showed no effect on future overweight (Klingenberg et al., 2013); however, other studies have found an inverse association between sleep duration and weight in children (Hart et al., 2011; Patel and Hu, 2008).

Taveras’s own work with a large cohort of infants and toddlers has found a relationship between sleeping less than 12 hours per day in infancy and higher BMI z-scores and increased odds of obesity at 3 to 5 years of age (Taveras et al., 2008). In follow-up studies of these same children, the highest prevalence of obesity in mid-childhood—when the children were 7 to 9 years of age—was seen among those who had the most exposure to insufficient sleep across infancy and early childhood (Taveras et al., 2014). According to Taveras, “It might not just be insufficient sleep in infancy but insufficient sleep in infancy and throughout early childhood that persists to affect BMI and potentially metabolic syndrome in mid-childhood.”

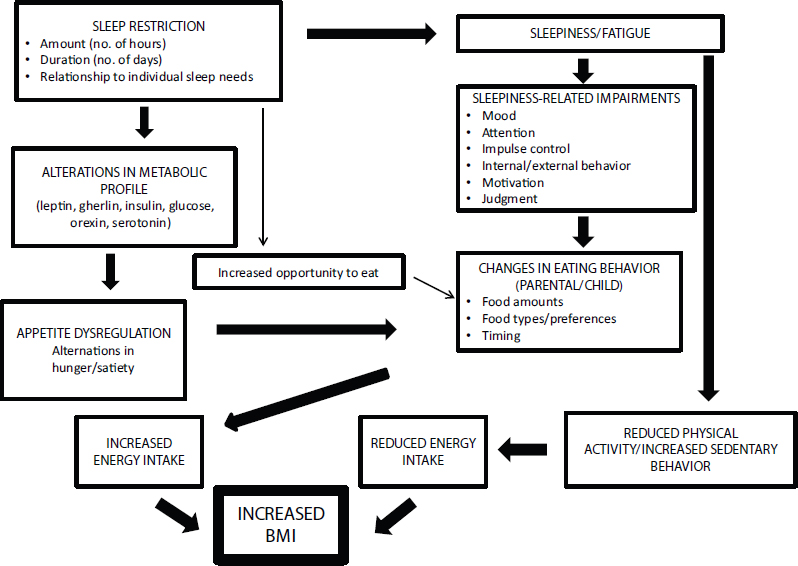

Most findings on the potential mechanisms underlying sleep and obesity relate to older children, but Taveras explained that among the possibilities are alterations in metabolic functioning, alterations in appetite hormones, and fatigue that affects the ability to participate in physical activity (see Figure 3-4) (also see Hart et al., 2011). Yet much remains unknown about the mechanisms relating too little sleep in infancy to rapid weight gain and obesity, she noted. Most studies have focused on sleep duration and have not examined other features of sleep, such as quality, timing, consolidation, regularity, ecology, and circadian alignment. Validated and objective measures of sleep characteristics are needed, Taveras asserted, rather than sole reliance on parental reports. Although good evidence exists for the efficacy of behavioral interventions in improving features of sleep in infancy, she observed, randomized controlled trials testing the effects of these interventions on future adiposity are lacking.

Shifting her attention to physical activity and sedentary behavior, Taveras pointed out that children are programmed to enjoy physical activity, but many environments and policies discourage such activity. Little is known about the normal range of physical activity and sedentary behavior in infancy and its association with energy balance, she noted. For example, only one study has quantified an association between infant screen time and childhood overweight. This study, involving 3,610 preschool children, found no association between television viewing in infancy and child obesity (Heppe et al., 2013), despite the robust literature on older children and

NOTE: BMI = body mass index.

SOURCES: Presented by Elsie Taveras on October 6, 2015 (with permission from Judith Owens, M.D., M.P.H., Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School).

adolescents relating television viewing and obesity. In addition, accurate measurement of infant activity remains a major challenge, Taveras suggested, although some work has successfully used accelerometry for this purpose (van Cauwenberghe et al., 2011).

According to Taveras, the evidence linking motor behaviors in infancy with adiposity is limited and observational. A longitudinal study of 741 mother–infant dyads found that none of the milestones of rolling over, sitting up, crawling, or walking were associated with BMI z-scores, though later age at walking was associated with greater overall adiposity at age 3 (Benjamin Neelon et al., 2012). A longitudinal study of low-income African American mother–infant dyads assessed from 3 to 18 months found that delayed infant motor development was associated with overweight and high subcutaneous fat (Slining et al., 2010). However, Taveras noted, no published randomized controlled trials have evaluated the effect of a physical activity intervention in infancy on increasing accelerometry-measured physical activity or preventing obesity, although the evidence on the inverse relationship between television viewing and physical activity among children 2 to 5 years of age is strong.

Among children aged 2 years and older, Taveras observed, studies that have tracked activity and sedentary behavior using accelerometers have demonstrated a consistent protective relationship of greater physical activity levels and less television viewing with decreased risk of obesity and other measures of adiposity (Monasta et al., 2010). “The robust association later in childhood means we really should be focusing on these behaviors early in life,” she suggested.

Finally, Taveras talked briefly about the early-life origins of racial and ethnic disparities in childhood obesity. Although, as noted in Chapter 1, some promising signs have appeared in the latest data, obesity remains at historically high levels among children, and some population groups are much more affected than others. As discussed in Chapter 2, among children 2 to 5 years old in the United States, 18 percent of Hispanic boys and 15 percent of Hispanic girls are obese, compared with a population average of 8.4 percent (Ogden et al., 2014). Among children aged 6 to 11, the corresponding percentages are 28.6 percent, 23.4 percent, and 17.7 percent (Ogden et al., 2014). Disparities also may exist before age 2 but may be partly disguised by methodological issues, Taveras suggested, such as the difficulty of obtaining accurate measurements. “If already, by 2 to 5 years of age, we have Hispanic children having five times the prevalence of obesity as their white counterparts, it means that those disparities are emerging early in life,” she said.

Taveras reported that childhood obesity has a number of determinants, many discussed by previous speakers, including

- gestational weight gain and gestational diabetes;

- maternal smoking during pregnancy;

- accelerated infant weight gain;

- breastfeeding;

- sleep duration and quality;

- television viewing and television sets in bedrooms;

- responsiveness to infant hunger and satiety cues;

- parental feeding practices;

- eating in the absence of hunger;

- portion sizes;

- fast food intake;

- ingestion of sugar-sweetened beverages;

- physical activity; and

- sociocultural factors, including the availability of opportunities for recreation.

With respect to almost every single one of these early-life risk factors, Taveras noted, black and Hispanic children have a higher prevalence of behaviors in early life that pose a risk for obesity (Taveras et al., 2010). In fact, when these risk factors are accounted for epidemiologically, they explain all of the disparities observed among population groups, she said. Based on some of that evidence, the report of a White House Task Force on Childhood Obesity suggests that racial and ethnic disparities in obesity may be explained in part by differences in risk factors during the prenatal period and early life (White House Taskforce on Childhood Obesity, 2010).

DISCUSSION SESSION: GUIDELINES FOR YOUNG CHILDREN

The discussion session addressed the development of dietary and other guidelines for young children. Saavedra pointed out that guidelines currently under development by the U.S. Department of Agriculture will go well beyond diet to encompass other indicators of healthy growth, such as physical activity and other behaviors. Although food is a critical factor, he said, “it is important to take a much more holistic approach as it relates to the guidelines, especially from zero to 2, if not from zero to 4.” The development of such guidelines will be a “huge step forward,” suggested Pérez-Escamilla. The dietary and physical activity guidelines for infants and toddlers, which should be completed by 2020, will fill “a huge gap that we know exists based on the maternal–child life course obesity cycle,” he said.