4

Effective Interventions: What Works?

In the third panel of the workshop, four presenters provided an overview of what is known about effective interventions in the early childhood years. The topics covered included interventions in pregnancy and the first 2 years of life to prevent childhood overweight and obesity, the role of pediatricians in obesity prevention, the potential of early care and education to stem obesity, and family-focused interventions in the home setting.

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS IN PREGNANCY AND THE FIRST 2 YEARS OF LIFE

Elsie Taveras of Massachusetts General Hospital for Children and Harvard Medical School, who gave the final presentation of the second panel, opened the third panel by reviewing interventions in pregnancy and the first 2 years of life that work to prevent childhood overweight and obesity. She and her colleagues conducted a systematic review of 34 completed studies of 26 such interventions (Blake-Lamb et al., 2016). Nine of these interventions, she reported, were found to be effective in improving childhood weight status. She and her colleagues also examined ongoing studies of such interventions summarized in the ClinicalTrials.gov database, noting a substantial increase in the number that were based in clinics and that were targeted at the individual level.

The interventions that worked were focused primarily on individual- or family-level behavior changes, Taveras observed. Interventions in homes, clinical settings, or group sessions held in community-based settings were equally effective. Taveras described four examples, one of which was the SLeeping and Intake Methods Taught to Infants and Mothers Early in Life Trial, described by Leann Birch during the workshop’s second panel (see Chapter 3).

The second example was the Healthy Beginnings Trial, which looked at 667 first-time mothers and their infants in socially and economically disadvantaged areas of Sydney, Australia (Wen et al., 2012, 2015). Taveras reported that community nurses conducted eight home visits lasting 1 to 2 hours, one occurring prenatally and the other seven in the first 2 years of life. The targets of the interventions were breastfeeding, infant feeding and activity, family nutrition, and activity. At 2 years of age, body mass index (BMI) was 0.29 kg/m2 lower on average in the intervention group compared with controls. By 5 years of age, however, there were no sustained effects on BMI or on dietary behaviors, quality of life, physical activity, or television viewing time. This was one of several interventions that worked in the short term but were not sustained in the long term after they ended, said Taveras.

The NOURISH randomized controlled trials recruited 698 first-time mothers and their healthy-term infants (Daniels et al., 2012a,b). As described by Taveras, two 3-month group education modules starting at ages 4-6 months and 13-16 months delivered a skills-based program focused on parenting practices that mediate children’s early feeding experiences and that include protective complementary feeding. When the interventions ended at 13-16 months, the intervention group had an average BMI z-score that was lower by 0.23 to 0.42 compared with the controls. At 2 to 5 years, the researchers found increased use of protective feeding practices but no difference in BMI z-score or prevalence of overweight or obesity. “Do we

define that as working?” asked Taveras. “I think so, with the caveat that I will mention later, which is maybe we need to think about this in a life-course approach, and as some intervention activities end, others need to be picked up to sustain those effects.”

Finally, Taveras described the Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project for Babies (STRIP), a longitudinal randomized controlled trial in which more than 1,000 infants and their families were randomized at 7 months of age to intervention and control groups (Simell et al., 2000). The intervention group received individualized dietary and lifestyle counseling at clinic visits every 1 to 3 months until the children were 2 years of age, twice per year until they turned 7, and yearly until they were 10, with a focus on diet and physical activity. At the outcome period of age 10 years, 10.2 percent of the intervention girls and 18.8 percent of the control girls were overweight; the boys showed no difference in percentages overweight.

Taveras also described several interventions that did not work. For example, protein-enriched formulas actually increased the risk of childhood obesity in the studies that she and her colleagues reviewed (Blake-Lamb et al., 2016). Also, none of the interventions focused only on pregnancy resulted in improved childhood obesity outcomes (Blake-Lamb et al., 2016).

Taveras cited several lessons learned from her review. First, obesity prevention programs need to be continued or maintained during the early childhood years and beyond, she said. This observation highlights the importance of a life-course approach, she suggested, with risk-reducing interventions being conducted over time in the settings where children spend their time.

The second lesson Taveras cited has to do with the role of eco (particularly environmental)-social (particularly family) contexts in the planning and sustainability of some interventions. “The most effective interventions were those that focused on the family and that attempted to change the environment,” she said.

The existing literature has a number of gaps, Taveras pointed out. None of the studies intervened on maternal prepregnancy BMI or prenatal tobacco exposure. “We need to try to find a way to reach women who are intending to become pregnant,” Taveras suggested, which is difficult since so many pregnancies are unplanned.

Taveras also mentioned that many infant feeding interventions have focused solely on breastfeeding, few have assisted women who were formula feeding, and none have focused on infants’ intake of sugar-sweetened beverages. She said, “We do a disservice to those women who have chosen to not breastfeed, to not be able to counsel them on responsiveness, or even how they can prevent obesity among their children who are being bottle or formula fed.”

Taveras pointed out further that systems-level and community-based interventions are underrepresented in the literature, although ongoing trials entail more of these kinds of interventions. In addition, null results tend not to be published, she observed, which limits the ability to generalize about what does not work.

Finally, Taveras mentioned that few interventions are attempting to change the social context or upstream influences on obesity, such as government policies (for example, food subsidies) and private-sector practices (for example, fast food marketing). Moreover, she asserted that, in general, most interventions are of suboptimal quality.

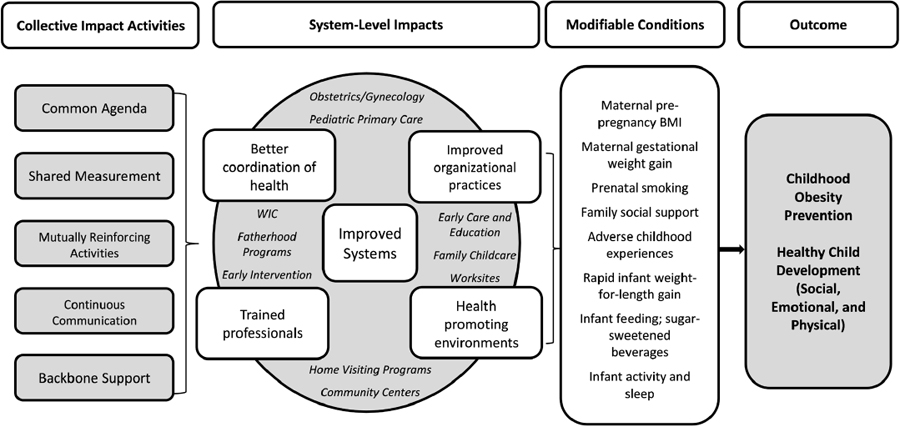

Taveras concluded her presentation by decrying the siloing of work on early childhood development, obesity prevention, and health promotion. As a pediatrician, she sees obesity prevention and child development as completely intertwined. “Focusing on obesity prevention shouldn’t mean that we don’t take the opportunity to also work on healthy child development when we have the opportunity in this critical period of life,” she argued. Accumulating evidence is showing that adverse early childhood experiences have effects on children’s development not just in the short term but in the long term as well. Initiatives focused on child development could take advantage of critical periods to lay a foundation for good nutrition, physical activity, sleep, and other important health behaviors. For example, Taveras is involved in an intervention in community health centers in the Boston area designed to change how families interface with all the different programs and settings—such as obstetrics and gynecology clinics, pediatric clinics, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), fatherhood programs, early child care and education, worksites, home visiting programs, and community centers—that affect not only obesity but also social, emotional, and physical development (see Figure 4-1). “Novel interventions that operate at systems levels hold promise for improving early life obesity prevention efforts,” she observed.

A CLINICIAN’S PERSPECTIVE ON INTERVENTIONS EFFECTIVE IN EARLY CHILDHOOD

As with interventions focused on the first 2 years of life, few interventions have focused on the prevention of obesity for children aged 2 to 5 years, observed Ian Paul, professor of pediatrics and public health sciences, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine; and chief of the Division of Academic General Pediatrics and vice chair of clinical affairs in the Department of Pediatrics, Penn State Hershey Children’s Hospital. However, interventions with motivational interviewing as a key component have had some success in the treatment of overweight, he observed. For example, Resnicow and colleagues (2015) used a Pediatric Research in Office

NOTE: BMI = body mass index; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

SOURCES: Presented by Elsie Taveras on October 6, 2015 (Blake-Lamb et al., 2016).

Settings network to conduct a 2-year trial of three groups of children 2 to 8 years old who were overweight or obese: one group that received usual care, one that received a motivational interviewing intervention, and a third that received a motivational interviewing intervention plus the attention of a registered dietitian. BMI improved in all three groups, with the members of the group that received both interventions showing the greatest improvement over 2 years.

“My talk would have been pretty short,” noted Paul, if not for the release of a recent report from the American Academy of Pediatrics. According to that report, “Pediatricians should use a longitudinal, developmentally appropriate life-course approach to help identify children early on the path to obesity and base prevention efforts on family dynamics and reduction in high-risk dietary and activity behaviors” (Daniels et al., 2015b, p. e275). “That sounds great,” said Paul. “Fortunately, they did also give us some specifics.” He then broke the report’s recommendations down into several categories (Daniels et al., 2015b).

First, pediatricians should identify children at risk, Paul said. For this purpose, they should use growth charts, prenatal risk factors, behavioral risk factors, and other measures.

Second, Paul said, pediatricians should educate. They should screen for knowledge about healthy diets and portion sizes; the risks of sedentary behavior; the role of WIC and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); and online resources, such as choosemyplate.gov.

Third, suggested Paul, pediatricians should help manage the food and activity environment by, for example, screening for risky behaviors. Examples of such behaviors include the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. If that behavior is identified, Paul said, pediatricians should suggest zero-calorie beverage alternatives.

Finally, Paul observed that the American Academy of Pediatrics has suggested that pediatricians should encourage self-monitoring (Daniels et al., 2015b). For example, families can keep diaries showing what behaviors are contributing to an obesogenic environment rather than a healthy environment. As with many issues in pediatrics, Paul suggested, “We want it to be a family-focused intervention. As we have heard before, obesity is not just a child problem. It is often a family problem.”

Pediatricians have a number of advantages in reaching out to children and families, Paul noted. They have good access to children and their parents or guardians, they are a trusted source of health information, and they can link families to community resources. However, Paul also listed the many barriers pediatricians face. They have time and space constraints, such as limited availability of clinic rooms. Appointments are short, typically just 15 to 20 minutes. Families must spend extra time to make more visits to pediatricians, and travel is difficult for some families. Physician

care is relatively expensive, and reimbursement for obesity-related care has been poor. Pediatricians do not always feel equipped to handle issues involving obesity prevention or even obesity treatment. They often lack knowledge or experience in preventing obesity for young children, and especially from birth to age 5, it can be difficult to convince families that there is a problem. As Paul noted, “We have heard about the chubby baby is a healthy baby. A lot of that goes on. Even for myself, when I look at a child that is 3 or 4 years old as the BMI curve hits its nadir [and] a child is at the 95th percentile, it is hard for me to . . . tell the parents that the child has a problem.”

The difficulty for pediatricians becomes clear, Paul suggested, if one examines the third edition of Bright Futures, which lists several priorities for a 2-year well child visit, including assessment of language development, temperament and behavior, toilet training, television viewing, and safety (Hagan et al., 2008). But none of the visits in years 2 through 41 lists diet or nutrition as a priority, he observed. Similarly, the questionnaire for parents from Bright Futures includes one question about food insecurity and whether a child is eating iron-rich foods, but no others related to nutrition or obesity prevention guidance. According to Paul, this omission suggests there is only so much pediatricians can cover in a single, annual office visit.

Paul stated that pediatricians use weight-for-length and BMI growth charts for every patient. Although many pediatricians have not used BMI growth charts in the past, some evidence indicates that this situation is changing. “However,” he said, “I can assure you that the weight-for-length chart for children under age 2 is almost never being used by pediatricians.” He noted that the American Academy of Pediatrics has set a clear criterion for infant overweight: weight-for-length equal to or greater than the 95th percentile (Daniels et al., 2015b). “Maybe that will cause [pediatricians] to pay some attention to [weight-for-length],” Paul suggested.

Paul closed by pointing to several hopeful signs. Quality improvement is becoming pervasive across U.S. hospitals, he noted, and it is moving from the inpatient to the outpatient setting. He suggested that the use of electronic health records could be leveraged to improve the delivery of primary care related to obesity—for example, by displaying high BMI or rapid weight gain as an alarm value. Previsit or waiting room surveys could be automatically loaded into the electronic record so that risky behaviors would be highlighted when the physician entered a visiting room.

New models of care could deliver primary care more efficiently and give pediatricians more face time with families, Paul noted. For example,

___________________

1 Early childhood tools: https://brightfutures.aap.org/materials-and-tools/tool-and-resourcekit/Pages/Early-Childhood-Tools.aspx (accessed April 20, 2016).

centering care2—a model of group health care entailing the three main components of assessment, education, and support—is starting to move from prenatal care into pediatric well child care, especially during the first year or two after birth (e.g., Mittal, 2011; Page et al., 2010). Pediatricians and dietitians also could partner with community programs such as WIC and farmers markets, Paul suggested. Communications between pediatricians and obstetricians could improve to encourage breastfeeding and smoking cessation during pregnancy, he added. Both groups also could communicate better with child care providers, which almost never happens today, Paul noted.

As a final example of partnering, Paul mentioned NET-Works (Now Everybody Together for Amazing and Healthful Kids Study), a randomized controlled trial involving an intervention that integrates home, community, primary care, and neighborhood strategies (Sherwood et al., 2013). The goal is to promote healthy behaviors, healthful eating, and activity and to prevent overweight and obesity among preschool-aged children. “I like this model because the primary care provider has a very defined role,” said Paul. “It is respectful of the lots of other things that a pediatrician has to do during a visit.”

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS IN EARLY CARE AND EDUCATION

More than 60 percent of U.S. children are in some kind of regular child care arrangement (Laughlin, 2013), stated Dianne Ward, professor of nutrition, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina. Collectively referred to as early care and education (ECE), these arrangements may be child care centers, family homes, Head Start programs, or prekindergarten programs. Children also may be in unlicensed or license-exempt care provided by neighbors, relatives, or friends.

“The ECE area has been identified as a missed opportunity” for obesity prevention, said Ward (Story et al., 2006). She noted that the experiences children have in these settings can affect health outcomes, diet, and physical activity. As reported by Reynolds and colleagues (2013), the ECE setting provides a spectrum of opportunities and multiple levels for the promotion of healthy practices (see Figure 4-2). At the most upstream level, Ward noted that public policies can affect the quality of young children’s experience in the ECE setting in many ways (Kakietek et al., 2014; Stephens et al., 2014; Wright et al., 2015). Licensure and standards for licensed facilities are one example, she said. Another is quality rating and improvement systems, including nutrition and physical activity standards. Block grant funding provided by the federal government to states can be tied to higher

___________________

2 See https://www.centeringhealthcare.org (accessed April 20, 2016).

SOURCES: (a) CDC, n.d.; (b) as presented by Dianne Ward on October 6, 2015 (Sallis et al., 2008).

quality and enhanced standards. And individual states have learning standards for ECE settings. “If we could include specific nutrition and physical activity standards,” Ward suggested, “this is another way that we might be able to affect what children experience.”

At the organizational level, policies and practices within facilities could influence the foods and beverages served, the amount of physical activity provided, and the amount of time spent in sedentary activities, Ward said (Alkon et al., 2014; Bonis et al., 2014; Drummond et al., 2009; Finch et al., 2012; Natale et al., 2014; Ward et al., 2008). Efforts to achieve an external ECE certification or rating also can enhance the experiences children have (Dowda et al., 2009).

Ward noted that a number of existing curricula used in ECE facilities focus on nutrition or physical activity. Although the data in this area are somewhat weaker, she argued that they cumulatively reveal an important impact. Also, she observed, providing structured physical activity lessons increases overall physical activity and fundamental motor skills, and training and technical assistance contribute to teachers’ ability to provide physical activity lessons (Alhassan et al., 2012; Annesi et al., 2013; Fitzgibbon et al., 2011; Parish et al., 2007; Reilly et al., 2006; Specker et al., 2004). Improvements in the quality of the outdoor play environment can include open areas, looping cycle pathways, grass hills, portable play equipment, and more space per child (Bower et al., 2008; Cosco et al., 2010; Nicaise et al., 2012). Other physical activity modifications with potential include providing more vigorous activity (Collings et al., 2013); reducing sedentary time (for example, having no chairs at some tables and taking regular breaks from sitting) (Hinkley et al., 2015); providing energizers during lessons (such as activity breaks) (Webster et al., 2015); and embedding physical activities within circle time, centers, and transitions (Kirk et al., 2013). Also at the organizational level, eating-related modifications with potential, Ward observed, include providing fruits or vegetables prior to main offerings; offering regular food tasting and cooking opportunities; creating a garden at an ECE program; instituting firm policies on foods brought from home, including food for celebrations; and using family-style dining (Mikkelsen et al., 2014; Ward and Erinosho, 2014).

Several research gaps in these areas need to be filled, Ward stated. The role of vigorous physical activity and its impact on the body composition of preschool-aged children needs to be explored, she said, as do the issues of reducing sedentary time and using energizers to provide elementary school children with more activity. Space limitations are a problem in most facilities, she noted, especially in urban facilities or in inclement weather, which may make it impossible to go outside. The role of teachers and the health of staff in developing healthy feeding and activity practices is still uncertain, she added, as is how best to engage parents.

At the interpersonal level, Ward noted, staff can promote healthy eating through role modeling, praising, providing informal education, prompting, using responsive feeding practices, and not using food as a treat or bribe. Although some evidence indicates that the way ECE professionals interact with children is directly associated with how children eat and what they consume, research gaps still exist in this area, she said. She added that even less is known about the role of ECE professionals in physical activity, with some evidence indicating that joining in play and being a role model are associated with more activity among children. “We need to do more research in this area,” she asserted, “particularly about providing informal education, prompting, and not punishing children for being active.”

Ward stated that an important issue that has not been well explored is how to engage parents in supporting the role of the ECE setting in the development of healthy eating patterns and regular physical activity. Some interventions have involved attempting to achieve parent engagement in a passive way by sending home newsletters or other notices, but Ward noted that a more effective approach is to incite some sort of response from parents. She suggested that good examples include the Hip Hop to Health, Jr. program (Fitzgibbon et al., 2011) and the Healthy Caregivers–Healthy Children (HC2) program (Natale et al., 2014).

Another area that needs additional consideration and research, Ward argued, is the health of child care providers, although the impact of their behaviors and health on children is largely unknown. Most ECE staff are low-income wage earners, she observed, garnering about minimum wage in many states. She noted that the few studies of their health that exist present a poor picture marked by obesity, poor diets, inactivity, stress, sleep irregularities, smoking, and other negative health behaviors and outcomes. “Yet these are the same people we ask to be role models, to be leaders, and to be educators with our children,” she observed.

Efforts are needed at all five levels—public policy, community, organizational, interpersonal, and the child—said Ward. Although opportunities exist at each level, she suggested that interventions that target multiple levels may be more successful. The Hip Hop to Health, Jr. program, for example, includes both an educational component focused on healthy eating and regular physical activity and a parent component. Over its 10 years of operation, it has shown a number of positive outcomes, Ward noted (Fitzgibbon et al., 2005, 2011).

Partnering between ECE settings and public health professionals through the use of licensure, ECE standards, and professional organizations provides many opportunities for progress, Ward said. Other opportunities include creating and distributing training opportunities in healthy eating and physical activity for ECE teachers; developing partnerships with

parents to support ECE; and offering comprehensive wellness programs for children, ECE staff, and families.

Ward concluded by pointing to several additional research gaps. Little is known about how to promote healthy eating and regular physical activity in family child care settings, she observed. Although some trials in this area are currently in progress, little of this work is looking at infant and toddler programs. And the effects of vigorous physical activity need to be explored to see whether that emphasis should be reintroduced to the ECE setting, Ward suggested.

EFFECTIVE INTERVENTIONS IN THE HOME SETTING

Since 2012 at least 16 randomized controlled trials of family-focused interventions for reducing obesity in children 5 years old or less have been completed, and another 9 are currently in progress or have results pending, noted Kirsten Davison, associate professor of nutrition, Harvard School of Public Health. These interventions involve repeated interactions with parents to modify parenting approaches and change child outcomes. “This research is increasing rapidly,” Davison said. She divided this research into three categories: promotion of healthy lifestyles, the combination of healthy lifestyles and parenting skills, and interventions targeting broader family life (reviewed by Sung-Chan et al., 2013).

In the first category, Davison said, are interventions focused on the family food environment, media rules, parents’ own diets, physical activity, and other components of a healthy lifestyle. Interventions target the timing of the introduction of solids, limits on sugar-sweetened beverages, having the television off during meals, meal-time routines, parental diet and modeling of physical activity, repeated exposure to vegetables, and the promotion of child motor development. Completed studies involving such interventions include Barkin et al. (2012), Campbell et al. (2013), Daniels et al. (2012b), Fitzgibbon et al. (2011), Schroeder et al. (2015), and Skouteris et al. (2010), while those with results pending include de Vries et al. (2015), Delisle et al. (2015), Eneli et al. (2015), Horodynski et al. (2011), and Sobko et al. (2011). Interestingly, said Davison, most studies conducted outside the United States fall into this category, while the other two categories consist mainly of U.S. studies.

The second category, said Davison, extends these interventions to include, for example, responsive parenting, child sleep routines, parenting style, child emotional regulation, and co-parenting. Completed studies in this area include Haines et al. (2013), Østbye et al. (2012), Paul et al. (2011), and Wen et al. (2012), while those with results pending include Paul and Birch (2012) and Ward et al. (2011).

The third category of interventions does not target obesity, Davison

observed, but could have effects on weight. For example, Brotman and colleagues (2012) focused on the prevention of conduct disorder among children in high-risk families, but one long-term outcome of this intervention was reductions in weight gain over time. Similarly, in studies discussed at conferences of the Society of Prevention Research on such topics as conduct disorder and antisocial behavior, changes in child BMI often have occurred, even when the researchers were not expecting such an outcome. “We are going to find multiple examples of this,” said Davison, although she characterized them as “harder to find.”

Davison drew several general conclusions from the studies of family-focused interventions. Six of the studies showed significant effects on child BMI, she noted, which is consistent with results of a meta-analysis by Yavuz and colleagues (2015). Similarly, a majority of the studies found significant effects on the mediator of interest. All four that involved a home setting showed significant effects on BMI, whereas the studies that involved a community setting had more mixed results. Also, the studies that involved low-income populations and racial and ethnic minorities were more successful than those that involved other populations. The length of the intervention did not have a noteworthy effect on the results, Davison said, and the studies with short-term follow-ups tended to show a greater effect than those with longer-term follow-ups. In fact, she observed, most of the studies that followed participants for more than 1 year found little long-term effect on weight.

One clear research gap noted by Davison is the development of sustainable family interventions whose effects are maintained. “Most programs focus on a specific cluster of behaviors and tend to be quite narrowly focused, in general, on diet and physical activity,” she said. “There may be real opportunities in partnering with people looking at different outcomes, whether it be oral health, child developmental disorders, and so forth.” In addition, she observed, most programs work with highly selected samples and are limited to a single setting. Family retention is a challenge, with dropout rates ranging from 32 percent to 73 percent (Skelton et al., 2011). Also, “what about dads?” Davison asked. “If we counted the number of times we have mentioned the word mother today and the times we have mentioned father, this is going to be a very disproportionate characterization. There is a great need for research in this particular area,” she argued. Davison described a preliminary content analysis of approximately 500 papers on parenting and childhood obesity published over the past 5 years, for example, only 9 percent of which present any results for fathers.

Davison concluded by describing a cluster of opportunities for further study of family-focused interventions. The first is an increased emphasis on translational research and the value of pragmatic trials, she suggested, which could lead to sustainable interventions. Likewise, she sees great

potential for integrating interventions into systems of care such as Head Start or school-based health centers to reduce selection bias and sustain intervention effects. Multisetting family-focused interventions are in progress, she noted, and there is increasing interest in engaging in fathers. “A real marker of this would be the release of an RFA [request for applications] focused on fathers,” she said. Finally, the integration of social media and web applications into family interventions could be considered to increase family engagement and reduce attrition.

DISCUSSION SESSION

Integrating Across Levels

During the discussion period, the panelists turned their attention to how to connect different interventions across settings, age levels, and institutions.

Taveras cited an approach she and her team have taken to initiate an intervention in a clinical setting and then continue it outside the clinic through community health workers, health coaches, and others (Taveras et al., 2015a,b). “We are also using quite a bit of social media and mobile technology to reach families outside of the clinical setting where, frankly, behavior change happens,” she said. “It doesn’t happen when they are seeing me in the clinic.” She argued that the designers of interventions need to think more creatively about reaching families in the settings where they spend much of their time.

Davison in turn cited the care demonstration projects, which have the objective of linking interventions across community sectors, including health care and community public health (Davison et al., 2015; Taveras et al., 2015a). Linking these sectors is a tremendous challenge, she said. Up-front planning and consistent messaging and materials across sectors are important, she added, along with heavy reliance on media. Community coalitions and regular opportunities for champions in different sectors to connect have potential in this area, she suggested.

Paul reiterated that “there is only so much that can be done in the pediatric office.” If pediatricians have a defined role, he suggested, community partnerships can reinforce the messages and behaviors they convey. He also mentioned the importance of the dose of an intervention. “A couple of exposures to messages over a short period of time are unlikely to have a sustained effect,” he said; rather, having a sustained effect requires multiple exposures over a longer time period.

Ward noted that professionals have opportunities to communicate with families, but they also need support from others, such as Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) consultants. Taveras, too, cited “missed opportunities to work within existing structures.” For example, she noted,

none of the systems-level interventions from pregnancy to age 2 have included the WIC program. “WIC is such a huge opportunity for children at high risk,” she said. “We are not working on childhood obesity in home visiting curricula. We are not engaging fatherhood programs. . . . We have to work at a systems level. We are really not doing that currently.”

In addition, Paul pointed to poor communication among sectors. Primary care physicians and child care professionals rarely interact. The WIC program “is giving messages that may be the same or different from what the parents are hearing from pediatricians,” Paul said. “For a lot of families, that can be very confusing. Who do I accept the information from? It would seem that the different aspects of early child health would have some way to communicate with each other, but we don’t.”

Ward observed that ECE professionals are receptive to wellness promotion opportunities, both for children and for themselves. A supportive environment and reinforcement of the efforts they make can help staff promote healthy nutrition and physical activity, she asserted.

Messaging and Empowerment

In response to a question about the messages that need to be sent, Paul said, “There is not a single silver bullet here as far as the message. There are various messages.” The message may need to be different for different communities and different racial or ethnic groups based on the norms of their culture, he added, and repeated messages from diverse stakeholders from different sectors of the environment across the life course may be needed to make a difference.

Paul also cited the effectiveness of a health literacy approach with very simple messages that use pictures. But he pointed out as well that different families have different issues: in one a child might drink soda all day, while in another a child might drink water but have four Pop-Tarts for breakfast. “There is not a one-size-fits-all intervention,” he argued.

Taveras observed that when parents and children are asked about the messages that would be most effective in changing their behaviors, the answers received are surprising. In a study of children with obesity who managed to return to a healthy weight, for example, the children said some of the things that motivated them were teasing about social stigmatization and peer relationships (Sharifi et al., 2015). Children want to fit into the clothing that other children their age fit into, Taveras observed. They do not want to shop for clothing at plus-size stores. They do not want to have to swim with a shirt on to hide their gynecomastia. “We sometimes fail to see that the answer to how to get families and children to change is by engaging those parents and children in helping us with the solution,” Taveras suggested.

Davison urged the leading public health organizations to develop a set of messages they all endorse. “If we have multiple organizations really pushing that, we will start to see those messages permeate consistently,” she asserted.

Ward mentioned efforts to get parents and ECE professionals to talk with each other. “The vast majority of parents are trying and want the best for their children, [but] they are a bit conflicted about how to get there,” she observed. She suggested that perhaps messages that relate to brain promotion through better food and physical activity could motivate parents in ways that current messages, such as having smaller portion sizes, do not.

Paul pointed to what he called stealth interventions. “Every new parent wants their baby to sleep as long as they can, myself included,” he said. “If we know that short sleep duration or poor sleep hygiene is a risk factor for childhood obesity and later obesity, and if we focus on the thing that is desirable to parents such as prolonging sleep duration, parents want that. . . . That is going to be better received than talking about obesity prevention [for] a 2-month-old.”

Roundtable member Shiriki Kumanyika of the University of Pennsylvania pointed to the onslaught of messaging that runs counter to efforts to control obesity. Messaging is needed that enables parents to “push back, to push the demand curve the other way [and] ultimately change the environment and then the dose,” she suggested.

Davison mentioned a pilot intervention in which she and her colleagues focused not on traditional diet and physical activity behaviors but on, for example, conflict resolution skills, media literacy, and parent resource empowerment (the ability to identify resources in the community that could benefit the family and then advocate for access to those resources) (Davison et al., 2013). “That is one example of how [parents] can push back and explicitly seek out those things,” she said.