5

Promising and Innovative Cross-Sector Solutions

During the workshop’s final panel, four presenters and the workshop participants in general looked across sectors to identify promising solutions to the problem of obesity in young children.

PROGRAMS AT THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

Diet-related disease and obesity have largely replaced malnutrition as the clinical consequence of food insecurity and hunger in the United States,

observed Kevin Concannon, under secretary for food, nutrition, and consumer services, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). USDA addresses both diet-related disease and food insecurity through 15 different programs, including the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP); and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

WIC, which began in Pineville, Kentucky, in 1974, is designed to safeguard the health of low-income, nutritionally at-risk women who are pregnant and postpartum, as well as the health of infants and young children. Today, WIC operates through 1,900 local agencies and 10,000 clinic sites nationwide, providing evidence-based supplemental food packages to more than 8 million participants monthly. About half of the infants born in the United States now participate in the program, Concannon observed. “The public health significance of WIC cannot be overstated,” he asserted.

Concannon explained that the WIC food packages, which were updated in 2009 to align with recommendations of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, emphasize fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and low-fat or nonfat milk and milk alternatives. In addition to the monthly food packages, WIC participants receive tailored nutrition education, breastfeeding education and support, counseling, and health promotion.

WIC has demonstrated a long-standing positive impact on breastfeeding rates, dietary intake, health outcomes, and health care costs, Concannon said. Since the food package was revised, WIC participants have been consuming more fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy products and less whole milk—diets with increased fiber and decreased saturated fat (Chiasson et al., 2013). According to Concannon, low-income communities have greater access to whole grains, fruits, and vegetables as a result of the changes. In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stated that the program has likely played an important role in the recent leveling off or decline in obesity rates among low-income preschoolers in 19 of the 43 states and territories that were studied (May et al., 2013). More robust information on WIC’s impact on early childhood obesity also is being gathered, Concannon noted. For example, USDA is in the midst of the longitudinal WIC Infant and Toddler Feeding Practices Study II (discussed by Jose Saavedra during the workshop’s second panel; see Chapter 3), which is following a nationally representative sample of infants who began WIC participation at birth through their fifth birthday.

Concannon particularly emphasized the potential to link WIC more closely to federally qualified health centers and other health care centers. At the local level, he said, many WIC clinics are collocated with public health care centers and health departments to facilitate integrated services. The

National Association of Community Health Centers reports that more than 1,200 health centers are operating through more than 9,000 delivery sites and are serving more than 22 million people each year, 10 percent of whom are children under age 5 (National Association of Community Health Centers, 2014). Additionally, Concannon reported that WIC has collaborated with the Arkansas Children’s Medical Center on a variety of research projects; has worked with pediatricians in Pennsylvania to optimize primary prevention of obesity; and has established clinics in four hospitals in the Southwest, including an Indian Health Service hospital.

Turning to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, Concannon explained that the current guidelines, which are published jointly by USDA and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services every 5 years, apply to children aged 3 years and older. At the time of the workshop, the next iteration of guidelines was about to be released. However, Concannon observed, work was under way to make recommendations for the period of pregnancy through 24 months of age as input for the committee working on the 2020 guidelines. “The current process is not one of developing but of beginning to assess the science,” he said. “The work on incorporating tailored advice for infants, toddlers, and women during pregnancy and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans is a separate process and will begin once the 2020 committee is in place.” Also under way at the time of the workshop was an update to the meal requirements for CACFP, which Concannon called “another important step forward.”

Two recent changes in law are driving efforts to strengthen USDA programs in health care settings, Concannon noted. The first is the SNAP nutrition education program, which includes $400 million in nutrition education grants to states spent annually under SNAP. The law now allows USDA grantees to promote policy systems and environmental change strategies and interventions to prevent obesity, Concannon observed, which will strengthen obesity prevention efforts in many feeding programs. The second change in law is the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which requires nonprofit hospitals to undertake community benefit programs based on community needs assessments. “Nutrition initiatives and assistance programs are ripe for inclusion,” said Concannon. “When I am on the road meeting with not-for-profit groups, I invariably bring this up as an area of opportunity.”

Even before the ACA community benefits requirement, Concannon noted, many health care organizations were partnering with USDA programs through SNAP. For example, since 2010 Blue Cross Minnesota has offered Market Bucks, a dollar-for-dollar match for each dollar SNAP participants spend on fresh produce using Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) cards. As another example, Concannon explained that some hospitals and health care complexes, such as Our Lady of the Lake Children’s Hospital in Baton

Rouge, Louisiana, and the Children’s Hospital in Arkansas, have established summer meal sites for all local children 18 and younger. In addition, major health care systems in the country, including the Cleveland Clinic, the Mayo Clinic, and ProMedica, have, he said, “taken the issue of food insecurity and obesity to heart and are engaging across several of our program fronts with community-based agencies, schools, child care centers, and food banks.”

Concannon also touched briefly on the importance of leadership. Drawing on his previous experience as a state director, he noted that some states take less advantage of the food and nutrition programs at USDA than others, even though they have the same opportunities to do so. “I am urging my colleagues within Food and Nutrition Consumer Services to, first and foremost, give state governments the opportunity to engage to participate,” he said. “If states are not engaged to participate, go looking for the health care systems, for the partnerships with counties, for other colleagues and other federal agencies to reach in to pursue some of these goals. The needs are severe that are out there. Strong leadership (and experience) can be successful even in challenging political environments.”

The United States still faces many challenges in food security and nutrition, Concannon concluded. For its part, he said, USDA is working “diligently to cross-sector our partnerships in an effort to leverage resources and enhance our public health impact.”

OBESITY PREVENTION IN NEW YORK CITY

According to Jeni Clapp, director of Healthy Eating Initiatives, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, obesity is responsible for more than 5,000 deaths annually in New York City, second only to tobacco as a cause of preventable deaths (according to a 2012 internal analysis by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Bureau of Epidemiology Services, and Bureau of Vital Statistics). Hospitalizations among adults with diabetes accounted for 24 percent of all hospitalizations in 2011 (Chamany et al., 2013), she reported, and the financial cost of obesity to New York City taxpayers is estimated to be about $1,500 per household per year (calculated based on Trogdon et al., 2012). “Needless to say, for a local health department, there are a lot of reasons why we want to address obesity,” she said.

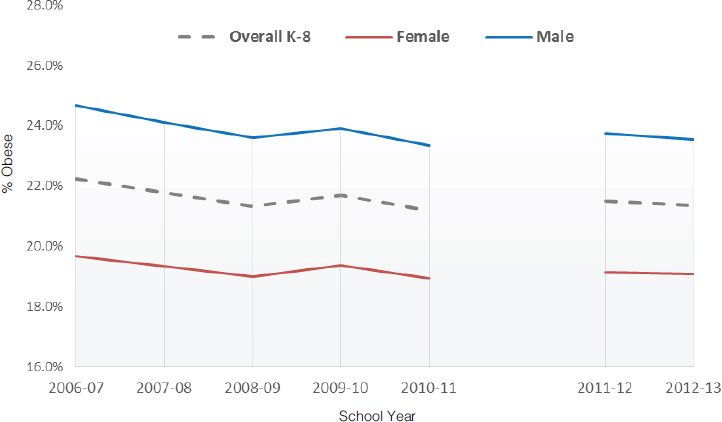

Clapp noted that obesity among K-8 students in New York City public schools is high but, as with the national trends cited in Chapter 1, has plateaued or slightly declined in recent years (see Figure 5-1). Efforts to reduce obesity in New York City have shown “promising results” among individuals with severe obesity (Day et al., 2014), she said, with the decline in severe obesity outpacing the decline in obesity generally. The reasons for the decline are not clear, said Clapp.

SOURCES: Presented by Jeni Clapp on October 6, 2015 (reprinted with permission, The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2014).

In 2005 the New York Department of Education implemented New York City FITNESSGRAM®, Clapp reported, and a partnership with the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene has yielded a database in which the height and weight of individual students can be tracked over time. This database, which Clapp noted contains more than 2.5 million records for nearly 950,000 unique students, has revealed greater reductions in obesity among non-Hispanic white and Asian-Pacific Islander children than among Hispanic and non-Hispanic black children, and greater reductions in low-poverty than in high-poverty neighborhoods (Berger et al., 2011). As a result, she explained, the obesity epidemic is continuing to affect disproportionately communities that are already experiencing health and economic disparities. “We still have a lot of work to do,” she asserted.

The health department in New York City is charged with improving the public’s health, Clapp noted. To this end, it focuses on meeting individuals where they are, improving their knowledge, augmenting their skills, and boosting the amount of money they have to spend on improving their health. It also tries to improve the environment in which people live, including stores, restaurants, marketing, and other factors that affect food decisions. “If you want an apple and you know that an apple is a

healthy snack, but the store nearby doesn’t sell it or the cost is relatively expensive or the quality is poor, you are a lot less likely to get that apple,” said Clapp. “Same thing with exercise. If there is not a gym or park nearby or it is expensive or your street doesn’t feel safe to you, you are much less likely to get that exercise. . . . We can’t control what happens everywhere, but we have a bit of control over public spaces and spaces that we regulate. We want to make those spaces the gold standard of health.”

Clapp described one such example of how New York City is addressing early childhood obesity. Approximately 2,000 public and private group child care centers in New York City care for about 130,000 children aged 0 to 5. The New York City Board of Health has long held independent regulatory authority over these centers, Clapp explained. In 2006 the Department of Health proposed to the Board of Health that it amend Article 47 of the city’s health code to establish requirements for healthful beverages, to strengthen requirements for physical activity, and to limit children’s screen time. An evaluation of the 2007 changes to Article 47 indicated that compliance was high, Clapp said.

In 2015, Clapp noted, Article 47 was amended again to update the screen time, nutrition, and physical activity requirements. She explained that the 2015 update reduced the amount of screen time allowed for children aged 2 years and older from 60 minutes per day to no more than 30 minutes per week, which is consistent with research findings; changed to 2 years the age at which 100 percent juice is permitted and reduced the amount to 4 ounces, which is consistent with CACFP recommendations; and decreased the amount of continuous sedentary time allowed for children from 60 minutes to 30 minutes except during scheduled rest, which is consistent with the IOM recommendations.

The Article 47 updates had champions at multiple levels of government, Clapp noted, and the changes could be made through regulation rather than through new legislation. Child care staff received education and training on structured physical activity and healthy eating to support the changes, particularly in low-income neighborhoods, she noted. In addition, food procurement standards for all city agencies that purchase and serve food or beverages, which cover about 250 million meals served by the city annually, were established to encompass nutrition criteria that include sodium limits, calorie limits, and fiber guidelines. “What this meant is that the message we were conveying wasn’t just to child care centers,” Clapp said. “It was a change that was happening across the city.” Complementary initiatives could help change the environment and shift social norms, she argued. “Incremental change is okay,” she stated. “We may not have all of the answers, but that doesn’t mean we can’t tackle some.”

Clapp reported that an evaluation looking at obesity prevalence among 3- and 4-year-old children enrolled in WIC, comparing high- and low-risk neighborhoods in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Manhattan, found a reduction

in prevalence after the 2007 Article 47 amendments were implemented, as well as a narrowing of disparities between high- and low-risk neighborhoods in the Bronx and Manhattan (Sekhobo et al., 2014). The relationship of these trends to compliance with Article 47 is unknown, Clapp noted, but research suggests that the trends may be due to the intensive assistance offered in high-poverty neighborhoods. “City-wide policies may be working in tandem with policies at other levels of government to change the food and physical activity environment for low-income preschool children,” she observed.

The policies affecting child care centers are part of a broader movement, Clapp noted. For example, policies to reduce the consumption of sugary drinks in New York City include not only the child care provisions but also the food procurement standards for city agencies, day camp regulations, and the city’s unsuccessful 2013 attempt to cap portion sizes. These local efforts have been supported by federal policies, changes in other jurisdictions, and hard-hitting media campaigns, Clapp said. As an example of the latter, she pointed to portion caps being featured on the television program Parks and Recreation, which drew a great deal of attention across the country and raised the visibility of the issue.

Clapp outlined several takeaway messages from the experience in New York City. First, she said, innovations are prioritized based on evidence, scalability, and sustainability—although she noted that the city also has taken some risks to innovate. Second, having supportive mayors who are committed to public health and poverty reduction has given city officials the freedom and support to pursue these initiatives. Third, efforts have been focused on neighborhoods where health outcomes are worst, with messages being reinforced through a combination of policies, programming, education, and media. Policies can set a benchmark, Clapp noted, with each new policy change raising the bar for the next set of changes. Finally, she suggested, the layering of policies and initiatives at different levels has bolstered the message of making the healthier choice the easier choice. “It continues to be the North Star for us,” she said.

In response to a question about how compliance with wellness policies is measured and enforced, Clapp said the approach in New York City is an extension of the public health model with respect to health and safety. It extends inspection, violation, and enforcement mechanisms to obesity and chronic disease, she said. Inspectors go into child care centers at least once a year, providing data for evaluation and further refinement of the approach.

OBESITY PREVENTION THROUGH HEALTH CARE PARTNERSHIPS

As a nonprofit pediatric health system, the Nemours Children’s Health System has a vested interest in the health of children, said Allison

Gertel-Rosenberg, the system’s director of national prevention and practice. Nemours offers pediatric clinical care, research, education, advocacy, and prevention programs, with the goals of improving child health and well-being and leveraging its own clinical and population health expertise.

In recent years, Nemours has been focusing on child health promotion and disease prevention to address the root causes of health, said Gertel-Rosenberg, with preventing childhood obesity and emotional and behavioral health problems being the first initiatives. In part, it has pursued this goal by complementing and expanding the reach of clinicians using a community-based approach. This approach reflects the fact that messages regarding healthy eating and physical activity need to extend across the life cycle, Gertel-Rosenberg observed, with consistent messaging from all of the key influencers in children’s lives, including parents, early care and education (ECE) providers, and physicians. “It is not this one thing or this one place that is going to do it,” she said. “It is the multitude of actions and how we work with our partners across those sectors [and] across that life span for the child.”

Key elements of Nemours’ strategy, explained Gertel-Rosenberg, are to define geographic populations and a shared outcome; establish multisector partnerships where children live, learn, and play; pursue policy and practice changes; develop social marketing campaigns; leverage technology; and serve as an integrator that works intentionally and systematically across sectors to improve health and well-being. She pointed out that many people at the workshop were fortunate to work in positions in which they could help think across sectors and break down silos. “Making the connections that need to happen and thinking through what synergistic effects can occur when we aren’t focused on one place or one time is an optimal role for us to play,” she said.

Gertel-Rosenberg reported that Nemours has undertaken a wide variety of programs to spread and scale healthy eating and active living in ECE settings. Through these programs, she noted, it can affect the lives of 800,000 children representing multiple populations. Nemours also has worked with many partners, such as the Sesame Workshop, with which it developed a toolkit using the Sesame Street characters to influence children in ECE settings. Most important, Gertel-Rosenberg asserted, ECE providers need turnkey solutions that are easy to implement so they do not need to struggle to figure out how to make something work.

Gertel-Rosenberg also suggested that efforts in formal ECE settings need to be coordinated with family providers, which typically do not have large enough staffs to spare people to attend a learning session. “We are thinking about how we can support these changes, how we can support these providers, and [how the] lessons we have learned can be taken forward and put into place in other initiatives that are going on around the country,” she said.

Nemours also has established learning collaboratives to enable peers to learn from each other, Gertel-Rosenberg noted. The system worked with the CDC to spread these collaboratives to 10 sites in nine states so as to leverage its investments. “This is a great example of initiatives that may start small and may look different as we spread and scale them,” Gertel-Rosenberg observed. “If you look at what we implemented in Delaware, it probably looks very different than what we have implemented in, say, California or in New Jersey, but it has the flavor.”

Changes in both policy and practice are stronger than either alone, Gertel-Rosenberg asserted. Federal levers, state levers, and local context all provide opportunities to achieve change. Furthermore, the changes accomplished benefit not just the current cohort of children but future cohorts as well, and staff become empowered to serve as role models. “For a lot of folks, it might be the first time that they are gardening. It might be the first time that they are talking about getting down on the floor, or going outside to play with the kids in their care,” Gertel-Rosenberg explained. “But when they are doing it, they are learning what it means, how to do it, and taking that to heart and figuring out what the next point of implementation is.”

Gertel-Rosenberg drew several lessons from her experiences:

- These programs represent an investment of time. “This is not something that we have gone into lightly,” she noted. “We thought a lot about how we can leverage their investments.”

- State organizations need more organizational capacity and bandwidth to manage and implement large projects.

- State organizations do not naturally think about weaving projects into existing initiatives (such as the CDC’s Spectrum of Opportunity). “The more that we can do to weave, make those connections happen, and figure out where the push buttons are, the better we are,” she argued.

- Asking center staff to become leaders and train their entire center is innovative, and it requires time and coaching to develop peer leaders and leadership teams.

- Buy-in and sustainability typically require balancing fidelity to a national model with state and local customization. “Figuring out what the key components are that need to be replicated is important, and then figuring out where key concepts can be tweaked, if you will, to fit the context of the local communities or states,” she explained.

- There are no perfect trainers; those strong in ECE tend to be weak in health and vice versa, which argues for pairing trainers that have strengths in each. The most important skill is relationship building and coaching with center teams.

- Technology can be a barrier. “We should be pushing on technology, but we should also be recognizing that technology may be a barrier,” she said. “We don’t want to turn people off to participation by putting high barriers into place.”

- Programs are often overwhelmed by the number of “quality improvement” efforts.

- Programs find it difficult to participate because of competing time demands (to attend sessions and do homework, for example). Many programs do not even have regular staff meetings.

- “Lunch box” programs in which children bring their food with them entail unique challenges, since they require that parents be more directly involved.

- Efforts to involve parents and support changes at home need to be more intentional.

THREE LESSONS FOR OBESITY PREVENTION

In the last formal presentation of the workshop, Terry Huang, professor at City University of New York School of Public Health, shared three lessons he has learned through his cross-sectoral work on obesity prevention.

The first is that building trust is “absolutely key.” This lesson “seems so simple, yet in practice is so hard,” Huang noted. Building trust takes time, resources, effort, and strategy, he said, yet this area “gets the least amount of attention by the biomedical and public health enterprise.”

For several years, Huang has been involved with a project focused on renovating and rebuilding a school that uses an innovative design to promote health. Many sectors have been involved in the project, including education, public health, design, and architecture. Evidence and theories related to healthy eating and physical activity have been translated into design strategies and language that designers and architects can use. Design thinking also has been extracted and adapted for a range of public health applications beyond this school building project. “Through this ongoing collaborative example, I have come to appreciate how much it takes to work across sectors,” Huang said. He also has been involved with an initiative at the National Institutes of Health involving a series of forums focused on building trust that have brought together sectors including the food and beverage industry, the media, public health, government, and academia to develop an environment in which the parties can devise innovative solutions for moving forward. “Again, that process taught me so much about how hard it is to actually do this work, but yet how important it is if we [are] to embark on a multistakeholder approach toward obesity,” Huang explained. Such forums, of which the roundtable that convened this workshop is an

example, can align the capacity of stakeholders with the complexity of the task, he argued.

The second lesson, Huang said, is the importance of partnerships, which, he asserted, can effectively leverage both collaboration and competition. Collaboration and competition may appear to be incompatible, he noted, but in the business world they can be structured on different levels to create a virtuous circle that leads to great innovation. In the ECE settings, for example, collaboration can occur at the local level while friendly competition at the state or regional level spurs widespread improvement, he suggested. “As teams become better at getting collaborative people to join them, they become more competitive over time,” he said. For example, teams with diverse and collaborative players allow their members to be creative and to innovate while they compete for resources tied to particular public health goals. Teams that lose out in a competition then can be reconfigured to sustain coordinated distribution of work, Huang explained.

The final lesson Huang cited is the need to continually reassess and reset the goals of the system. In the school design project he described, for example, the original goal of promoting healthy eating and active living has evolved to the larger goal of fostering a culture that is imbued simultaneously with the values of learning, sustainability, and well-being. “We have these low-income children who are now going home during summer recess and saying how much they miss school,” Huang noted. “If I can keep these kids all in school throughout the academic year and get them involved in the summer, there are all sorts of great things that will happen for [them] down the road apart from health impacts.”

These lessons derive in part from what Huang called “translational systems science”—the idea that insights from diverse fields and disciplines about complex systems can inform innovative public health solutions. This idea, he argued, provides alternative ways of organizing the roadmap going forward beyond traditional biomedical thinking. For example, he has been working with the health department in Victoria, Australia, to launch a systems-oriented change initiative designed to transform the prevention system. This initiative has scaled up the systems thinking capacity of the department’s prevention workforce, he asserted, while also creating a network of distributed actions and functionalities throughout the components of the prevention system, both at the local level and vertically between the local and state levels. The most important issue may not be the dose of a particular program delivered, suggested Huang, but the strategy behind the dose, as evidenced by the importance of aligning the capacity of the actors and the complexity of the task.

As another example of translational systems science, Huang called attention to the work that needs to be done to shift social norms and create a demand for obesity prevention, healthy places, healthy products, and

healthy policies. Such shifts in demand make it more likely that advantageous policies will be adopted and prove beneficial, he argued. In turn, resetting the goals of the system leads to new research questions, new strategies, and new ways to understand and affect complex systems. “Many of those are very different than what we are dedicating our time and resources to right now,” Huang noted.

DISCUSSION SESSION

Creating Systems Change Across Sectors

In the discussion session, the panelists and the panel moderator discussed an issue at the heart of the Roundtable on Obesity Solutions: transcending place-based success stories to create the kinds of systems change needed for a sustainable solution. As was observed by moderator Lisel Loy, director of the Nutrition and Physical Activity Initiative at the Bipartisan Policy Center, bringing together talent from all of the sectors involved poses many challenges. “We are talking about building personal relationships,” she said. “We are talking about investing the time it takes to build trust across sectors, among people who don’t work together very often. We are talking about patience for incremental change. It is not all going to come at once. We are talking about site-specific and local changes, because that is the nature of the beast. There is no one size fits all. There is no off-the-shelf answer.”

Gertel-Rosenberg observed that leadership is key to moving forward. Leaders exist in different places in different communities, she noted. If change is to be systemic rather than episodic, leaders need a “bookshelf” of options from which people, organizations, and communities can select. By using a combination of the best options and by incorporating feedback loops to change or strengthen those options, Gertel-Rosenberg asserted, different parts of interconnected complex systems can move forward coherently.

Huang offered three options for synthesis of efforts. First, he suggested that public health education should train people not just for academia or city health departments but for a much wider variety of roles, “to create agents of change across sectors.” Preparing students to assume leadership roles in all industries and all sectors calls fundamental aspects of pedagogy into question, Huang argued.

Huang’s second suggestion was that leadership needs to be part of community readiness. To address obesity, he argued, communities need to be ready to address health as an issue. “If we actually spent more time and effort on building up community readiness, that [would] go a long way in changing the leadership landscape locally and nationally,” he said.

Finally, Huang suggested the need to create demand-side strategies that can help integrate bottom-up pressure and top-down strategies. A parallel, he believes, comes from the gay marriage movement in the United States. “If you look into the literature and the archives of how the U.S. gay marriage movement came about,” he said, “there are clear lessons for how we can get better organized. So much of the outcome of a social movement like the gay marriage movement in the U.S. is a shift in leadership, with a coordinated and distributed action plan.”

Fostering Sustainability

Related to the discussion of systems change was an exchange regarding how to create “business plans” that make initiatives sustainable and therefore impactful. Loy pointed out that a systems approach can engage the sectors that have a stake in the outcome of an initiative so that they make up-front investments in both changing systems and delivering outcomes, because change is in their interest. In particular, where health and wellness interventions intersect with the health care delivery system, she suggested, great potential exists to create sustainable financing models. In the context of the shift toward more value-based and integrated systems of care, she asserted, prevention can be embedded within coordinated systems that are based in the outcomes public health advocates share with business to bring new funding streams to the table.

Added Huang, “There can be no sustainable business model if our definition of a multistakeholder approach is limited only to the public sector or the academic sector.” The private sector must be involved in crafting long-term solutions, he argued. Business initiatives geared toward health can be profitable, he noted, even for the food and beverage companies, but “a strategic, coordinated, and managed effort with clear accountability mechanisms built in” is required. As an example, he cited the need for a cohesive effort across the public, private, and academic sectors to shift social norms, whether around portion sizes, the value of healthy products, or the pleasure of wellness.

Gertel-Rosenberg pointed to a dual strategy that, unfortunately, may require a double payment at the beginning, when resources are needed both for the current reality and for what will happen in the future. The challenge is to combine current investments with thinking about the potential long-term roles for organizations, whether in the health care or education sector. “We have devised a system where, if one sector gains, another loses,” Gertel-Rosenberg noted. “There is going to have to be a shifting of the norms, a broadening of the pie, if you will, where a redistribution is not a loss but rather a gain across shared goals and expectations.”

Finally, Concannon observed that the ACA is helping to create a sus-

tainable set of strategies for communities based on the reality that prevention saves money in the acute care system. “That is a plus on the health care side,” he said, “but it is also a plus for the industries and businesses that are paying [insurance] premiums.” Similarly, he noted, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act is creating systemic change in school meals, partly as a result of government’s engaging other organizations at the state and local levels. “We are trying to see what else can we do at the state level,” he said. “You can’t solve the hunger problem in this country with food programs. You need a much fuller commitment to engaging people in constructive ways so they have incomes.”