1

Introduction

The loss of hearing—be it gradual or acute, mild or severe, present since birth or acquired in older age—can have significant effects on one’s communication abilities, quality of life, social participation, and health. Despite this, many people with hearing loss do not seek or receive hearing health care. The reasons are numerous, complex, and often interconnected. For some, hearing health care is not affordable. For others, the appropriate services are difficult to access, or individuals do not know how or where to access them. Others may not want to deal with the stigma that they and society may associate with needing hearing health care and obtaining that care. Still others do not recognize they need hearing health care, as hearing loss is an invisible health condition that often worsens gradually over time. Finally, others do not believe that anything can be done to help them or feel that the perceived benefit or value of the service or technology will not be significant enough to overcome the perceived barriers to access.

In the United States, an estimated 30 million individuals (12.7 percent of Americans ages 12 years or older) have hearing loss.1 Globally, hearing loss has been identified as the fifth leading cause of years lived with disability (Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators, 2015). The unmet need for hearing health care is high. Estimates of hearing aid use are that 67 to 86 percent of adults who might benefit from hearing aids do not use

___________________

1 The study, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, found that these estimates of bilateral hearing loss increase to 48.1 million Americans (20.3 percent) when those with unilateral hearing loss were included (Lin et al., 2011).

them.2 Data on the use of hearing health care are difficult to obtain given the current structure of the hearing health care model.

Successful delivery of hearing health care enables individuals with hearing loss to have the freedom to communicate in their environments in ways that are culturally appropriate for them and that preserve their dignity and function. Key goals in improving hearing health care are that it be affordable, accessible, effective, accountable, person centered, person directed, and transparent while being supported by a larger society that prioritizes communication, reduces stigma, and provides social and environmental supports for hearing health. Embracing such a system goes well beyond the medical model and acknowledges and demonstrates respect for individuals’ needs, concerns, and goals.

SCOPE OF THE STUDY AND STUDY PROCESS

This report examines the hearing health care system, with a focus on nonsurgical technologies and services, and offers recommendations for improving the access to, the affordability of, and the quality of hearing health care for adults of all ages.

To address the study’s statement of task (see Box 1-1), the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine appointed a 17-member committee with expertise in hearing health care services, audiology, otology, hearing loss advocacy, primary care, geriatrics, health economics, technology policy and law, and epidemiology. Brief biographies for each of the 17 members of the committee can be found in Appendix B. The study was sponsored by (alphabetically) the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Defense, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Food and Drug Administration, the Hearing Loss Association of America, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

The committee held six meetings during the course of its work; the first four meetings included public sessions with speakers providing their expertise on a variety of topics relevant to the statement of task (see Appendix A). The committee also held a public conference call with invited speakers. In addition, the committee gathered information from the scientific literature and reviewed information submitted by members of the public and from various agencies and organizations.

___________________

2 These estimates are based on studies of hearing aid use in older Americans. Bainbridge and Ramachandran (2014) reported that 33.1 percent of potential hearing aid candidates (70 years and older) reported using hearing aids. Chien and Lin (2012) reported that 14.2 percent of Americans with hearing loss (50 years and older) use hearing aids.

OVERVIEW OF HEARING AND HEARING LOSS

Sound is produced by waves of air pressure that vary in frequency, amplitude, and direction. When working without impairment, the human auditory system—through a series of complex processes that are carried out in the ear and the brain—can quickly detect, distinguish, and interpret complex mixtures of sound waves from spoken, musical, and other types of audible communications (see Box 1-2).

Two dimensions of sound are its frequency (roughly analogous to pitch, measured in hertz [Hz]) and its intensity (the main determinant of the loudness of the sound measured in decibels [dB]) (see Table 1-1). Typically, humans can hear sounds from low to high pitch with frequencies between 20 and 20,000 Hz and at levels as low as 0 dB hearing level3 (dB HL). At high levels of intensity (and depending on the duration of the sound and proximity to the source) there is a risk of permanent or temporary pain or damage to hearing ability (CDC, 2015a). Results of a hearing test are shown in an audiogram, which is a graph that shows the lowest levels in each ear that an individual is able to hear sounds at each of several different frequencies. Other tests of hearing may also be conducted to differentiate between various causes of hearing loss and to better understand an individual’s communication challenges and needs (see Chapter 3).

The World Health Organization defines hearing loss as “not able to hear as well as someone with normal hearing—hearing thresholds of 25 dB HL or better in both ears” (WHO, 2015). The threshold is the minimum sound level at which an individual can detect any sound. Hearing loss is often cat-

___________________

3 The term “dB hearing level” (db HL) is a unit of sound used for pure tone audiograms and is referenced to levels of normal hearing specified in national and international standards. Decibel measurements may also be provided using sound pressure level measures, a logarithmic measure of sound pressure relative to a reference value.

TABLE 1-1

Examples of Sound Frequencies and Intensities

| Sound Frequencies (measured in hertz [Hz]) | |

|---|---|

| 250 to 1,000 | Vowel sounds, such as the short “o” in the word “hot” |

| 1,500 to 6,000 | Consonant sounds, such as “s,” “h,” and “f” |

| 20 to 20,000 | Typical range of human hearing |

| Sound Intensities (measured in decibels [dB]) | |

| 10 | Normal breathing |

| 25 to 30 | Whisper |

| 45 to 60 | Typical talking |

| 85 | Lawnmower |

| 90 | Sounds can become uncomfortable to hear |

| 110 to 140 | Rock concert (varies) |

| 120 or louder | Sounds may be painful |

| 0 to 140 | Typical range of human hearing |

SOURCES: CDC, 2015a; NIDCD, 2010.

egorized as mild, moderate, severe, or profound. Individuals with mild to moderate hearing loss may develop strategies to improve communication, such as facing the speaker or speech (lip) reading, and they may use hearing aids and hearing assistive technologies. Hearing aids are the most widely used intervention for adults with mild to severe sensorineural hearing loss. People with severe to profound hearing loss may be candidates for cochlear implants (a surgical intervention not addressed by this committee).

The committee focused on hearing loss, the major population-based hearing concern in adults, but recognized that there are a number of other conditions, such as tinnitus, which affect hearing health. Many of the recommendations in this report will be of benefit to the care of a range of hearing-related conditions.

Causes and Types of Hearing Loss

Hearing loss can be present from birth or can have an onset at any age. The causes of hearing loss are often categorized based on whether they are congenital or acquired. Congenital causes are those that lead to hearing loss or deafness at birth or soon thereafter. Examples of congenital causes of hearing loss or deafness are genetic syndromes; maternal rubella, syphilis,

or certain other infections during pregnancy; low birth weight; lack of oxygen at birth; certain drugs used during pregnancy (e.g., aminoglycosides, cytotoxic drugs, antimalarial drugs, and diuretics); and severe jaundice in the neonatal period (birth to 1 month). Genetic factors are responsible for an estimated 50 to 60 percent of childhood hearing loss in developed countries (Morton and Nance, 2006). Universal newborn hearing screening has been the standard of care throughout the United States since the early 1990s (CDC, 2015b; Morton and Nance, 2006).

Acquired hearing loss may be sudden or gradual in onset and may be caused by meningitis; measles and mumps; otosclerosis (progressive fusion of the ossicles of the middle ear); chronic ear infections; autoimmune or inflammatory disorders; fluid or infection in the ear (otitis media); tympanic membrane (ear drum) thickening or perforations; the use of some antibiotic, antimalarial, or cancer chemotherapeutic medications; some head injuries or other trauma; long-term exposure to excessive noise; cerumen (ear wax) or foreign bodies blocking the ear canal; or aging (presbycusis) (WHO, 2015). Some of these conditions (including otitis media, ear canal blockages, and some forms of otosclerosis) can result in conductive hearing loss, which affects the outer or middle ear, and are often medically or surgically treated. Sudden or fluctuating forms of sensorineural hearing loss may improve with medical or surgical treatment. However, most sensorineural hearing loss is the result of permanent changes to the cochlea, auditory nerve, or central auditory nervous system and cannot be repaired using current medical or surgical interventions. Thus, the most common interventions for sensorineural hearing loss are those that amplify sound to provide sufficient audibility of speech and other sounds. These interventions may include technologies, such as hearing aids and hearing assistive technologies, and auditory rehabilitation services, including auditory and speech perception, speech (lip) reading training, and training to improve communication and coping strategies.

Age-related hearing loss (presbycusis) has been documented in many mammalian species and is characterized in humans by increased hearing thresholds, the impaired processing of higher-level sounds (including reduced frequency and temporal resolution), and difficulty understanding speech, especially in noisy or complex listening environments (Yamasoba et al., 2013). The primary pathology of the process is unknown, but age-related hearing loss is a cumulative disorder which may involve both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including genetic mutations, the degeneration of cellular structures in the cochlear lateral wall, age-related loss of auditory nerve fibers, and neural changes in the brain affecting signal processing and interpretation. All of these affect the ability of the inner ear and higher neural centers to process acoustic signals and effectively separate the primary speech signal from interfering speech and noise. Regardless

of which auditory pathways are affected, the functional consequences will likely include an inability to hear some sounds (particularly high-frequency sounds); an inability to understand subtle differences in spoken words (e.g., “desk” and “debt”), especially in noisy environments; a poorer ability to process acoustic information quickly; and difficulty identifying sources of sound (Roth, 2015; Yamasoba et al., 2013). Generally, individuals present with symmetrical loss which is more apparent with high-frequency sounds and which is commonly more severe in men than in women (Van Eyken et al., 2007; see Chapter 2). Age-related hearing loss is very common, but its rate varies across populations (see Chapter 2), and some people retain excellent hearing well into late ages. There is strong evidence that genetic susceptibility contributes to the variation (Cruickshanks et al., 2010). The etiology of age-related hearing loss is not known, but there is emerging evidence that many potentially modifiable factors (e.g., smoking, adiposity, and vascular disease) are associated with the risk of developing age-related hearing loss (see Chapter 2).

DEFINITIONS AND TERMINOLOGY

As it began its work, the committee recognized the need to determine and then convey the definitions it was using for the key terms in its charge (“affordability” and “accessibility”) as well as for various hearing-related terms used in the report. This report uses the term “hearing health care” to encompass the range of services (e.g., diagnosis and evaluation, auditory rehabilitation; see Chapter 3) and hearing technologies (hearing aids and hearing assistive technologies; see Chapter 4) relevant to hearing loss. The committee viewed hearing health care through the social-ecological model (discussed later in this chapter) to emphasize the multiple levels of support and action needed throughout society to promote hearing and communication and reduce hearing loss and its effects. For the purposes of this report the term “hearing health care professionals” is used broadly to encompass those who work in hearing health care (including audiologists, hearing instrument specialists, and otolaryngologists). The term is used throughout the report primarily for ease—that is, one collective term rather than listing each group repeatedly throughout the report—and is not meant to imply any other meaning outside of the report context. The committee also notes that its use of the phrase “mild to moderate hearing loss” is inclusive of the spectrum from mild through moderate hearing loss.

Defining Affordability and Accessibility

Because the committee’s charge focused on improving the affordability and accessibility of hearing health care, clear definitions of these two

terms are critical to the discussions in this report. Access has been defined as “the timely use of personal health services to achieve the best possible health outcomes” (IOM, 1993, p. 33). This definition focuses on both the use of appropriate health services and on improved health outcomes from such services. The 1993 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report goes on to state, “The test of equity of access involves determining whether there are systematic differences in use and outcome among groups in society and whether these differences are the result of financial or other barriers to care” (IOM, 1993, p. 33). Thus, affordability is a part of access. If health care—be it determining the need for health care, visits to the health care provider, or the prescribed treatment—is too expensive for the individuals affected, it will not be accessible. The definition of access used by Healthy People 2020 incorporates four components: reimbursement coverage, services, timeliness, and workforce (HHS, 2015). As will be discussed in this report, if hearing health care (services and technologies) is to become truly accessible, it will be vital to address the geographic, language, and cost barriers to such care.

It is challenging to define affordability in the context of a specific product or service. Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines afford as “to be able to pay for (something); to be able to do (something) without having problems or being seriously harmed” and affordable as being “within someone’s ability to pay; reasonably priced” (Merriam-Webster, 2015). Affordability at the individual or family level thus largely depends on household income versus necessary expenditures. For example, the Department of Housing and Urban Development notes that families who “pay more than 30 percent of their income for housing are considered cost burdened and may have difficulty affording necessities such as food, clothing, transportation and medical care” (HUD, 2015). An estimated 12 million U.S. households (renter and homeowner) pay more than 50 percent of their annual income for housing (HUD, 2015).

As discussed in Chapters 4 and 5, the price of hearing aids (often bundled with the price for hearing health care services) have often been cited as deterrents to purchase and access, and because there is a general lack of options for hearing health care coverage for most adults (e.g., private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid) these products and services are not affordable for many potential users. The median household income in the United States was estimated by the U.S. Census Bureau to be $53,657 in 2014, with 33.7 percent of all American households having an annual income of less than $35,000 (DeNavas-Walt and Proctor, 2015). Among Medicare beneficiaries, half had an annual income below $24,150 in 2014 (Jacobson et al., 2015). The decision of whether to purchase hearing aids and the associated services (often the initial price is several thousand dollars or more, plus there are ongoing maintenance and, eventually, replacement costs; see

Chapter 5) must compete with decisions about whether to purchase other necessities. Thus, many individuals must make choices about what will fit into their budget and may forego hearing health care to meet other needs.

Hearing-Related Terminology

The hearing abilities of individuals can vary widely across the life span. Some individuals are born without the ability to hear any sound, while others may experience hearing loss either acutely or gradually, with the extent of the hearing loss ranging from mild to profound. Thus, appropriately defining and categorizing those various abilities and their effects on communication can be a challenge.

Individuals who are considered to be deaf generally have profound loss of hearing at most or all frequencies. The term “deaf” when used with a capital “d,” Deaf, often is used to refer to a community and culture of individuals who share a language (American Sign Language) and cultural values and priorities (NAD, 2015; Padden and Humphries, 1988). How individuals choose to refer to themselves is often influenced by the type and nature of the individual’s hearing challenges, age of onset of hearing loss, preferred communication methods, personal preferences, and support community (NAD, 2015).

The term “hearing impaired” has been used extensively, especially by professionals who use it as a single term to cover all types and degrees of hearing loss, but for the individual with hearing loss the term may bring with it the connotation of focusing on limitations and functional challenges (NAD, 2015). Although the term “hearing loss” is generally used to indicate hearing function that is poorer than normal in the population, the term may not apply to individuals who were born with some degree of hearing difficulties that remain unchanged over time, as they did not lose an ability they never had (NAD, 2015). The term “hard of hearing” has also been used, often as a way of differentiating the degree of hearing loss from deafness (e.g., “deaf or hard of hearing”), but the committee did not find it to be descriptive of the condition.

This report makes every attempt to use hearing-related terms in a manner that is conscientious and respectful of all people who are touched by hearing-related challenges. The committee’s task (see Box 1-1) is to focus on adults who use nonsurgical methods to address their hearing conditions; therefore, the committee chose to primarily use the term “hearing loss,” while acknowledging that some people who use hearing aids or other nonsurgical services and technologies have had hearing difficulties since birth. The report addresses issues of importance to individuals with deafness and to the Deaf community; however, deafness is not the focus of this report.

Another question of terminology relates to the different roles people are in when they address hearing loss and interact with hearing health care professionals. A person with hearing loss may at various times be a patient seeking care and treatment options, a consumer making purchasing decisions, or an individual participating in his or her community and seeking the best ways to meet his or her communication needs. A person can be in one, two, or all three of these roles at the same time. The committee uses the terms interchangeably to some extent, while trying to use the terms as appropriately as possible in a given context.

WHY FOCUS ON ACCESSIBILITY AND AFFORDABILITY OF HEARING HEALTH CARE NOW?

Hearing health care is in the midst of many of the same major challenges that the health care system, public health, and society in general are now facing. The following overview briefly explores several reasons why there is a critical need for a comprehensive study of hearing health care focused on improving its accessibility and affordability. Many of the issues discussed here are examined in greater depth in the chapters that follow.

Changing Demographics: Intersection of Hearing Loss and Aging

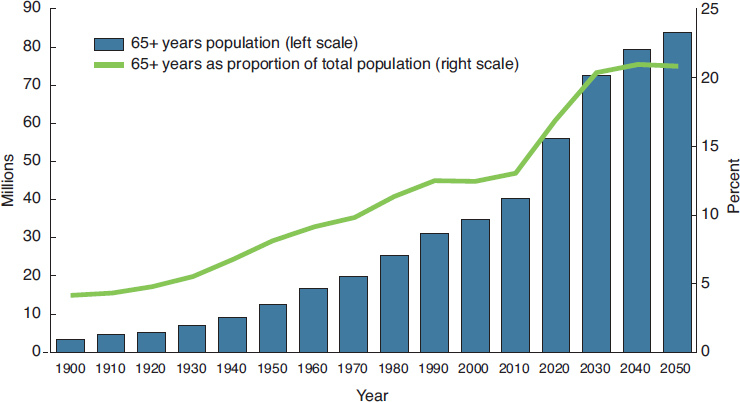

In the United States, as in many other countries, the median age of the population is increasing, and older individuals are living increasingly longer, during which time aging-associated chronic conditions—and, often, multiple such conditions in a given individual—may emerge and challenge health and social systems (Halter et al., 2009). As a result, it is likely that larger numbers of people will have hearing loss and require and seek care in the coming years. The demographic composition of the U.S. population has been influenced by several factors, including increased life expectancy, improved health care and nutrition, and changes in birth and mortality rates. In 1900, 4.1 percent of the U.S. population (just more than 3 million people) was 65 years or older; by 2012 that age group accounted for 13.7 percent of the population (more than 40 million people); and it is projected that by 2060, individuals 65 years and older will constitute 24 percent of the U.S. population (see Figure 1-1; ACL, 2016; Colby and Ortman, 2015; West et al., 2014). Similar aging trends are occurring around the world (NIA and WHO, 2011).

Hearing loss is a common chronic disability in older adults, can escalate with age, especially in those over 80 years of age (see Chapter 2), and its effects on verbal communication and, as a consequence, on social interactions and functional limitations have serious public health implications. Limitations in activity associated with chronic conditions, including hearing

SOURCE: West et al., 2014.

loss, affect greater numbers of older adults as age increases, and the functional impact of hearing loss may be magnified by the coexistence of other such conditions. As the population ages, more people may have moderate to severe hearing loss, which could require more services and potentially more complex services.

Recognizing Hearing Loss as a Public Health Priority and a Societal Responsibility

Long seen as an issue for individuals (and to some extent their families and friends), there is a growing realization that hearing loss is a significant public health concern that is influenced and affected by decisions and actions at multiple levels of society. Loss of hearing may lead to a reduction in quality of life due to communication challenges that can affect interactions with others and that have the potential for effects on cognition, behavior, and other aspects of health (see Chapter 2). However, the application of successful strategies to overcome the functional challenges of hearing loss and enhance communication capabilities can increase an individual’s participation in meaningful activities (see more on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health in Chapter 3).

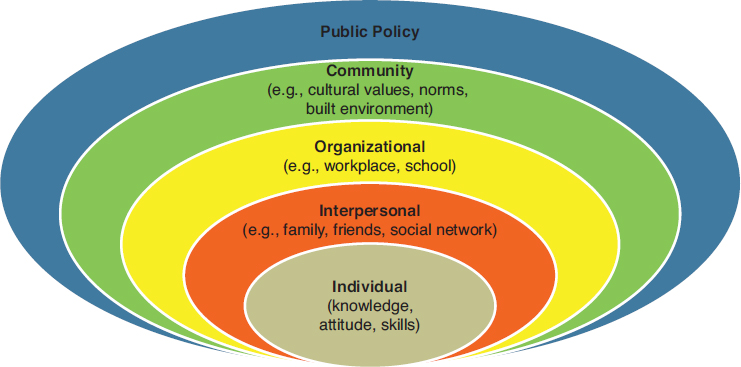

Centered on the individual, the social-ecological model (see Figure 1-2) illustrates the relationships and interactions among personal and environmental factors across society that play a role in hearing health: indi-

SOURCE: NIH, 2016. Reprinted with permission.

vidual; family, friends, and other interpersonal relationships (including peer-support groups); organizational (including supports through school, post-secondary education, and workplace); community (ranging from the built environment and acoustics in public spaces to destigmatizing hearing loss); and public policy and regulation (regulations on technologies or policies regarding health insurance coverage or other issues).

The social-ecological model has been more fully developed for other health issues, such as obesity prevention, where factors outside of the individual (e.g., available foods, access to opportunities for physical activity, and public policies on school lunches) play a role in choices, behaviors, and actions (CDC, 2013; IOM, 2005). The relevance of this model to hearing loss can be found in the breadth of responsibilities and actions that encompass successful hearing health care. The committee emphasizes the social-ecological model throughout this report, with particular attention in Chapter 6 to the multiple levels of supports and actions involved in hearing health care.

Rapidly Changing Technologies

The pace of technology change and adoption is accelerating at ever-increasing rates (McGrath, 2013). As discussed in Chapter 4, hearing-related technologies are rapidly evolving and moving toward more wearable and integrated systems. Recently, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology released a report on devices and products for older

adults who have mild to moderate hearing loss in which they noted “the unnecessarily high price of hearing aids for individuals and the conspicuously slow pace of innovation by their manufacturers compared with other consumer electronics” (PCAST, 2015, p. 9; also see Chapter 4).

“Hearables” is a relatively new term used to denote a wide range of hearing- and ear-based technologies with various and often multiple purposes which include communication, entertainment, fitness tracking, and physiologic measures in addition to enhancing hearing capabilities. Technologies specific to hearing include hearing aids as well as personal sound amplification products and hearing assistive technologies that connect the user with the television, the telephone, and public sound systems. It is critical that all sectors of hearing health care are fully engaged in these advances and are fully utilizing effective technologies to improve hearing and communication and to assure interoperability and connectivity. These new opportunities and technologies necessitate a call for a critical review of current policies and approaches and increased attention to fully informing the public, particularly those with hearing loss, about the range and capabilities of the options.

Changes in Health Care Paradigms

The hearing health care system is largely unknown to or difficult to penetrate by the general public. Routes for accessing hearing health care go through both business-driven and health care-driven pathways, with sparse information available on the appropriate pathways for individuals to gain access to the services and technologies best suited to meet their needs (see Chapter 3). Health care in general is also undergoing transformations that can propel hearing health care forward, and priorities have been identified which can be applied and incorporated into hearing health care (see Box 1-3).

Efforts are focused on patient-centered care that is evidence-based with attention to quality, safety, and value. Team-based care is also a priority, with teams that include the patient and family in addition to the relevant health care professionals. Principles identified as key to team-based health care are shared goals, clear roles, mutual trust, effective communication, and measurable processes and outcomes in a continuous loop of improvement (Mitchell et al., 2012). Additionally, emphasis on a learning health care system will be of great benefit to hearing health care. As defined, a learning health care system is “one in which science and informatics, patient–clinician partnerships, incentives, and culture are aligned to promote and enable continuous and real-time improvement in both the effectiveness and efficiency of care” (IOM, 2013, p. 17).

Health care encompasses a broad network with widely varying resources and skills applied to a vast array of health concerns. Neverthe-

less, progress is being made and efforts put forward that coordinate and integrate hearing health care into the evolving broader health care system. Hearing health care, throughout all of its diverse professional and patient care pathways, offers a wealth of opportunities for fully engaging in changing the paradigms and embracing the quality measures and actions that can improve care for individuals with hearing loss. Opportunities include the exploration and evaluation of diverse delivery and payment systems (see Chapters 3 and 5).

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

In examining the complex issues around hearing loss in adults and hearing health care, the committee developed a set of principles that helped shape its work.

- Prioritize the needs of individuals with hearing loss—The committee’s priority was concern for individuals with hearing loss and, in particular, on ensuring that these individuals have opportunities for accessible and affordable services and technologies to meet their communication needs. Accordingly, the committee’s work focused solely on what it deemed best for consumers/patients/individuals and not on meeting the needs of specific professions or industries.

- Emphasize hearing as a public health concern with societal responsibilities and effects—Actions needed to improve hearing and promote communications for individuals with hearing loss require a public health approach that involves efforts across multiple levels of communities and society. The impacts of hearing loss on individuals, families, and society require broad attention to this public health issue, including reducing the stigma often associated with hearing loss. Efforts to improve hearing environments and promote communication can yield benefits for all members of society.

- Move toward equity and transparency—Opportunities for improving hearing health care will require that services and products are available to those who need them across the socioeconomic and geographic spectra. Options for selecting those services and products need to be provided in transparent and itemized formats that meet the various health literacy levels of all adults and with data that compare effectiveness based on outcomes and cost using peer-reviewed research.

- Recognize that hearing loss may require a range of solutions—No one solution will work for everyone with hearing loss, and therefore the committee emphasizes the range of needs, solutions, and opportunities across the various levels of severity in hearing loss, types of hearing loss, and ways to mitigate hearing loss, maximize hearing, and improve the hearing environment. The goal is a person-centered, person-directed continuum of care across the life span.

- Improve outcomes with a focus on value, quality, and safety—Changes are occurring at a rapid rate in hearing health care technologies and in the delivery of hearing health care services, and actions will be required to ensure that these efforts are coordinated, safe, evaluated, and focused on best practices that provide value in improving hearing and communication capabilities for individuals with hearing loss.

- Work toward an integrated approach that provides options—The committee provides an approach to hearing health care that integrates services and technologies as appropriate to meet each person’s needs. Accessibility, affordability, and awareness are some of the key barriers that contribute to individuals not being able to optimally use hearing health care. Hearing aids and hearing assistive technologies are tools that benefit from careful and unbiased diagnostic and functional assessments of an individual’s needs and that can be supplemented by auditory rehabilitation services as appropriate. Creating a variety of options can help enable individuals with hearing loss overcome the specific barriers they face.

ORGANIZATION OF THIS REPORT

This report covers the breadth of the committee’s statement of task. Chapter 2 focuses on population-based studies and provides an overview of the evidence on the extent and impact of hearing loss. The focus of Chapter 3 is on hearing health care services, with overviews of the range of hearing health care professionals and the services they provide and with particular attention paid to improving the accessibility of hearing health care services. Hearing technologies are the area of emphasis in Chapter 4, which includes details on current regulations and the committee’s recommendations for change. The affordability of hearing health care (technologies and services) is examined in Chapter 5, with discussions of current coverage and exploration of the opportunities to make hearing health care more affordable. Chapter 6 explores issues spanning multiple areas of the community and society that affect access to and use of hearing health care. The report concludes in Chapter 7 with a call to action on hearing health care that will require efforts and collaborations across the range of involved parties, including individuals; families; health care professionals and organizations; employers; insurers; hearing technology industries; government agencies at the local, state, and federal levels; and the general public.

REFERENCES

ACL (Administration for Community Living). 2016. Administration on Aging (AoA): The older population. http://www.aoa.acl.gov/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2013/3.aspx (accessed March 14, 2016).

Bainbridge, K. E., and V. Ramachandran. 2014. Hearing aid use among older U.S. adults: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2006 and 2009–2010. Ear and Hearing 35(3):289-294.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) 2013. Social ecologic model. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/health_equity/addressingtheissue.html (accessed January 11, 2016).

CDC. 2015a. Hearing loss in children: About sound. http://www.cdc.gov/nc/bddd/hearingloss/sound.html (accessed December 21, 2015).

CDC. 2015b. Hearing loss in children: Data and statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/data.html (accessed November 2, 2015).

Chien, W., and F. R. Lin. 2012. Prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine 172(3):292-293.

Colby, S. L., and J. M. Ortman. 2015. Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf (accessed December 3, 2015).

Conners, B. W. 2003. Chapter 13: Sensory transduction. In Medical physiology, 1st ed., edited by W. F. Boron and E. L. Boulpaep. Philadelphia: Saunders. Pp. 325-358.

Cruickshanks, K. J., W. Zhan, and W. Zhong. 2010. Epidemiology of age-related hearing impairment. In The aging auditory system: Perceptual characterization and neural basis of presbycusis, edited by S. Gordon-Salant, R. Frisina, A. N. Popper, and R. R. Fay. New York: Springer. Pp. 259-274.

DeNavas-Walt, C., and B. D. Proctor. 2015. Income and poverty in the United States: 2014. Current Population Reports P60-252. http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p60-252.pdf (accessed February 18, 2016).

Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. 2015. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386(9995):743-800.

Halter, J. B., J. G. Ouslander, M. E. Tinetti, S. Studenski, K. P. High, S. Asthana, and W. R. Hazzard. 2009. Hazzard’s geriatric medicine and gerontology, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

HHS (Department of Health and Human Services). 2015. Healthy People 2020 topics and objectives: Access to health services. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/Access-to-Health-Services (accessed February 6, 2016).

HUD (Department of Housing and Urban Development). 2015. Affordable housing. http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/program_offices/comm_planning/affordablehousing (accessed December 30, 2015).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1993. Access to health care in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

IOM. 2004. Hearing loss: Determining eligibility for Social Security benefits. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2005. Preventing childhood obesity: Health in the balance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2013. Best care at lower cost: The path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Jacobson, G., C. Swoope, and T. Neuman. 2015. Income and assets of Medicare beneficiaries, 2014-2030. http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-income-and-assets-of-medicare-beneficiaries-2014-2030 (accessed March 28, 2016).

Lin, F. R., J. K. Niparko, and L. Ferrucci. 2011. Hearing loss prevalance in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine 171(20):1851-1853.

McGrath, R. 2013. The pace of technology adoption is speeding up. Harvard Business Review, November. https://hbr.org/2013/11/the-pace-of-technology-adoption-is-speeding-up (accessed December 4, 2015).

Merriam-Webster, Inc. 2015. Dictionary. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/affordable (accessed December 30, 2015).

Mitchell, P., M. Wynia, R. Golden, B. McNellis, S. Okun, C. E. Webb, V. Rohrbach, and I. Von Kohorn. 2012. Core principles and values of effective team-based health care. Discussion paper, Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC. http://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/VSRT-Team-Based-Care-Principles-Values.pdf (accessed April 5, 2016).

Morton, C. C., and W. E. Nance. 2006. Newborn hearing screening—A silent revolution. New England Journal of Medicine 354(20):2151-2164.

NAD (National Association of the Deaf). 2015. Community and culture—Frequently asked questions. https://nad.org/issues/american-sign-language/community-and-culture-faq (accessed December 21, 2015).

NIA (National Institute on Aging) and WHO (World Health Organization). 2011. Global health and aging. NIH Publication 11-7737. https://d2cauhfh6h4x0p.cloudfront.net/s3fs-public/global_health_and_aging.pdf (accessed December 3, 2015).

NIDCD (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders). 2010. Common sounds. http://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/education/teachers/pages/common_sounds.aspx (accessed February 8, 2016).

NIDCD. 2014. NIDCD fact sheet: Noise-induced hearing loss. https//www.nidcd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Documents/health/hearing/NIDCD-Noise-Induced-Hearing-Loss.pdf (accessed April 4, 2016).

NIDCD. 2015. NIDCD fact sheet: Hearing and balance. How do we hear? https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Documents/health/images/howdowehear-_pdf_version.pdf (accessed April 4, 2016).

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2016. Social and behavioral theories: Social ecological model adapted from U. Bronfenbrenner, 1977. http://www.esourceresearch.org/Default.aspx?TabId=736 (accessed March 14, 2016).

Padden, C., and T. Humphries. 1988. Deaf in America: Voices from a culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

PCAST (President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology). 2015. Aging America & hearing loss: Imperative of improved hearing technologies. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/microsites/ostp/PCAST/pcast_hearing_tech_letterreport_final3.pdf (accessed February 7, 2016).

Roth, T. N. 2015. Chapter 20: Aging of the auditory system. In Handbook of clinical neurology, Vol. 29, 3rd series, edited by G. G. Celesia and G. Hickok. Edinburgh: Elsevier.

Van Eyken, E., G. Van Camp, and L. Van Laer. 2007. The complexity of age-related hearing impairment: Contributing environmental and genetic factors. Audiology & Neurology 12(6):345-358.

West, L. A., S. Cole, D. Goodkind, and W. He. 2014. 65+ in the United States: 2010. U.S. Census Bureau special studies. http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p23-212.pdf (accessed December 3, 2015).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2015. Deafness and hearing loss fact sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs300/en (accessed October 23, 2015).

Yamasoba, T., F. R. Lin, S. Someya, A. Kashio, T. Sakamoto, and K. Kondo. 2013. Current concepts in age-related hearing loss: Epidemiology and mechanistic pathways. Hearing Research 303:30-38.