7

Toward a High-Quality Clinical Eye and Vision Service Delivery System

Encouraging high-quality eye and vision care is one component of a comprehensive population health approach to reduce vision impairment in the United States. As defined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), quality care must be safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient-centered (IOM, 2001). Currently, the clinical eye and vision service delivery system faces several challenges to achieving these goals. Multiple and sometimes conflicting clinical practice guidelines create different standards from which to measure and improve quality and clear, consistent public messaging about what care is needed when. Limited integration among and between clinical and public health services, combined with insufficient cross-disciplinary training of the workforce, may negatively affect diagnosis and follow-up care. Inadequate health care services research on the vision care system further hampers the ability to improve care quality through application of continuous quality improvement programs.

This chapter focuses on improving the quality and consistency of eye and vision care in the United States. The first section discusses the importance of consistent evidence-based guidelines to inform care seeking and providing behaviors, especially in the context of vision screenings and comprehensive eye examinations. The second section examines the role of continuous quality improvement initiatives in promoting high-quality eye and vision care. The third section explores potential integrated models of care to promote detection and diagnosis of vision problems and subsequent referral to eye care providers. The state of, and need for, cross-disciplinary education of the public health, eye care, and broader clinical workforce is described in the final section, with a focus on training to promote cultural

competency, leadership, teamwork, and awareness of the interrelations between eye and vision health, general health, and population health.

THE NEED FOR EVIDENCE-BASED GUIDELINES: ESTABLISHING THE BASELINE

Evidence-based guidelines are an important foundational element to anchor a population health approach that advances eye and vision health. First, they provide guidance based on sound, objective evidence that a variety of care providers can use to improve the uniformity of messaging about, and the quality of, patient care. Second, they establish a baseline from which to measure improvement in care processes and patient health outcomes. Third, they promote a culture of accountability by enabling performance comparisons and encouraging the uniform adoption of best practices.

To promote clear and consistent messaging about whom needs what care and when, it is important that a single set of evidence-based guidelines be available to the public, especially in the context of vision screenings and comprehensive eye examinations. Evidence-based guidelines released by the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Optometric Association (AOA), which are based on a review of the literature, serve to guide the members of the respective organizations in the treatment and management of eye diseases.1 These organizations use some of the same literature from which to develop their guidelines and, in many cases, offer consistent guidelines or recommendations. However, there are important differences, especially on topics related to the frequency of exams, specific types of treatments, and the use of screenings. These differences may be due to a confluence of factors, including guideline development processes, evidentiary standards, and professional emphasis of optometrists and ophthalmologists.

This section is intended to describe some of the current inconsistencies and challenges related to clinical practice guidelines in eye and vision health and to reiterate the standards to which clinical practice guidelines should be held. This section does not endorse any particular set of professional guidelines nor make conclusions about the quality of evidence supporting any specific guideline.

___________________

1 Clinical practice guidelines developed by AAO are referred to as “Preferred Practice Pattern® guidelines,” whereas clinical practice guidelines developed by AOA are referred to as “Clinical Practice Guidelines” or “Optometric Clinical Practice Guidelines.” Throughout this report, AAO and AOA clinical practice guidelines will be referred to as “guidelines,” or, wherever the distinction is pertinent, as “evidence-based guidelines” or “consensus-based guidelines.”

Distinguishing Comprehensive Eye Examinations from Vision Screenings

A comprehensive eye examination is a dilated eye examination that may include a series of assessments and procedures to evaluate the eyes and visual system, assess eye and vision health and related systemic health conditions, characterize the impact of disease or abnormal conditions on the function and status of the visual system, and provide treatment and follow-up options (see Chapter 1). Eye examinations can detect incipient eye disease before the onset of visual symptoms. Eye examinations can also detect chronic conditions, such as diabetes and multiple sclerosis (Crews et al., 2016; Frohman et al., 2008). Schaneman and colleagues (2010) conducted a retrospective, claims-based analysis of employed adults living in the United States, and found that individuals who detected a chronic disease through an eye examination had lower first-year health plan costs and fewer missed work days and were less likely to terminate employment than individuals who did not detect chronic conditions early through eye examinations.

Eye examinations are performed by ophthalmologists and optometrists and usually include taking a patient history, assessing the patient’s visual functioning (e.g., visual acuity, field of vision, eye movements), observing indicators of eye health (e.g., intraocular pressure), and examining the state of the pupil, iris, cornea, lens, optic nerve, retina, and other parts of the eye after dilation (AAO, 2012a). Eye providers may also perform the procedures listed in Box 7-1, along with cover tests, color blindness tests, depth perception tests, and other supplementary tests. Comprehensive eye examinations may last 45 to 90 minutes, and may require the use of photoropters, keratometers, tonometers, gonioscopy, diagnostic testing, and anesthetic and pupillary dilating eye drops (AAO, 2012a, 2016c; AOA, 2015d).

Vision screenings are tools that allows for the possible identification but not diagnosis of eye disease and conditions. Screenings are available for a variety of diseases and conditions, such as refractive error, eye problems in children, diabetic retinopathy, and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (AAPOS, 2014; Garg and Davis, 2009; Jain et al., 2006). Vision screenings can be used by both optometrists and ophthalmologists, as well as by other health care professionals, as a public health tool in community settings to identify potential vision problems early and to assist in the collection of evidence-based population vision health data (AAPOS, 2014). Vision screenings are used to identify issues with visual functioning or symptoms suggestive of an eye disease or condition. Box 7-2 lists a number of examples of common vision screening tests.

There is significant debate among professional and advocacy organizations about the role of vision screenings in clinical eye and vision care. Comprehensive eye examinations and vision screenings have different

strengths and weaknesses, and each serves a different role in the promotion of eye and vision health. In general, the findings of eye examinations are more complete, accurate, precise, and broader in scope than the results of vision screening. A comprehensive eye exam is more sensitive and specific and can precisely measure the extent—and identify the cause—of decreased visual acuity and the presence of eye disease and disorders and conditions of the eye and visual system, in addition to providing other assessments of eye health and functioning. The costs of comprehensive eye examinations are briefly mentioned in Chapter 6.

On the other hand, vision screenings have the potential to improve eye and vision health through potentially less expensive and resource-intensive

means of identifying specific vision problems, especially in children. For example, visual acuity tests using a letter or symbol chart, autorefractor, or photoscreener can be performed in a few minutes by a school nurse at no cost to the patient, or by primary care providers as part of a comprehensive physical examination. However, the effectiveness of vision screening as a diagnostic tool varies among patient populations, and depends on the screening tools used and the diseases or conditions targeted by screening (Chou et al., 2016a,b; USPSTF, 2011). Furthermore, studies have reported low or inconsistent rates of referral and follow-up care for individuals with abnormal screening results (Hartmann et al., 2006; Hered and Wood, 2013; Kemper et al., 2011).

The cost-effectiveness of screening can be sensitive to the eye disease or conditions and vision impairment risk profile of the targeted population, the screening interval, the diagnostic accuracy of screening tools, the staffing models used in a screening program, the rate of follow-up after abnormal screening results, the efficacy of available clinical treatments, and numerous other factors. Research on these and other issues is needed, but remains limited (Azuara-Blanco et al., 2016; Blumberg et al., 2014; Burr et al., 2007; Ladapo et al., 2012). The cost-effectiveness of vision screenings and comprehensive eye examinations is considered further in Chapter 6.

Conflicting study results and relatively limited research on the cost-effectiveness of vision screenings for specific eye diseases and conditions and comprehensive eye examinations for asymptomatic patients can also impede efforts to align existing guidelines (see, e.g., AHRQ, 2012; Burr et al., 2007; Gangwani et al., 2014; Jones and Edwards, 2010; Karnon et al., 2008; Rein et al., 2012a,b).

Advancing Evidence-Based Guidelines

Guidelines for Comprehensive Eye Examinations

Although comprehensive eye examinations are generally accepted as the gold standard in clinical vision care to most accurately identify and diagnose eye and vision problems, different professional groups often disagree on the age and frequency at which different patient groups should specific services. Both the American Academy of Ophthalmology and AOA recommend that at-risk populations receive more frequent eye exams. For example, the American Academy of Ophthalmology and AOA guidelines and/or policy statements both indicate that the frequency of age-related eye examinations should increase with advancing age, but AOA supports shorter intervals for testing at each age (AAO, 2015a; AOA, 2015d). In addition, AOA recommends that persons ages 18 to 39 without symptoms or risk factors be seen at least every 2 years, whereas the American

Academy of Ophthalmology states that “a routine comprehensive annual adult eye examination in individuals under age 40 unnecessarily escalates the cost of eye care” and is not indicated without specific risk factors or symptoms (AAO, 2015a; AOA, 2015d). Table 7-1 compares AAO and AOA guidelines on the frequency of comprehensive eye examinations for patients by age group with and without risk factors or symptoms.

TABLE 7-1 Comparison of AAO and AOA Guidelines for Frequency of Comprehensive Eye Examinations for Adults

| AAO | AOA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages | Without Risk Factors or Symptomsa | Higher Risk Groupsb | Ages | Without Risk Factors or Symptomsc | At-Risk Groupsd |

| Adults under age 40 | 5–10 yearse | Every 1–2 years | 18–39 | At least every 2 yearsf | At least annually or as recommended |

| 40–54 | Every 2–4 yearsg | Every 1–3 years | 40–64 | At least every 2 yearsh | At least annually or as recommended |

| 55–64 | Every 1–3 years | Every 1–2 years | |||

| 65 and older | Every 1–2 years | Every 1–2 years | 65 and older | Annuallyh | At least annually or as recommended |

a Intervals in this column apply to individuals who lack “symptoms or other indications following the initial comprehensive medical eye evaluation.” These intervals account for “the relationship between increasing age and the risk of asymptomatic or undiagnosed disease” (AAO, 2016c).

b Intervals in this column apply to individuals with glaucoma risk factors. The recommended frequency of eye exams varies among eye disease risk factors (AAO, 2016c).

c Intervals in this column apply to “asymptomatic, low risk” individuals (AOA, 2015d).

d Intervals in this column apply to “[p]ersons who notice vision changes, those at higher risk for the development of eye and vision problems, and individuals with a family history of eye disease.” AOA states that “adult patients should be advised by their doctor to seek eye care more frequently than the recommended re-examination interval if new ocular, visual, or systemic health problems develop” (AOA, 2015d).

e AAO states that “routine comprehensive annual adult eye examination in individuals under the age of 40 unnecessarily escalates the cost of eye care” and is not indicated without specific risk factors or symptoms (AAO, 2015a).

f AOA Consensus-Based Action Statement (AOA, 2015d).

g AAO states that “[a]dults with no signs or risk factors for eye disease should receive a comprehensive medical eye evaluation at age 40 if they have not previously received one” (AAO, 2016c).

h AOA Evidence-Based Action Statement (AOA, 2015d).

SOURCES: AAO, 2015a, 2016c; AOA, 2015d.

Guidelines for pediatric populations may also differ. For example, AOA guidelines on pediatric eye and vision examinations recommend comprehensive eye examinations for both asymptomatic/risk-free and at-risk pediatric patients. Table 7-2 details AOA recommendations on the frequency of pediatric eye examinations. By comparison, the American Academy of Ophthalmology states that “[c]omprehensive eye examinations are not necessary (but can be performed) for healthy asymptomatic children who have passed an acceptable vision screening test, have no subjective visual symptoms, and have no personal or familial risk factors for eye disease” (AAO, 2012b). It further recommends eye examinations for children who “fail a vision screening, are untestable, have a vision complaint or an observed abnormal visual behavior, or are at risk for the development of eye problems” and, where appropriate, for children with learning disabilities to rule out the presence of eye and vision problems, and for children with intellectual disabilities, neuropsychological conditions, or behavioral issues that cause them to be otherwise untestable (AAO, 2012b).

The American Academy of Ophthalmology and AOA guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of specific eye diseases may also vary in terms of the recommended frequency of eye care. For example, the American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines on primary open-angle glaucoma

TABLE 7-2 AOA Recommended Frequency of Comprehensive Eye Examinations for Pediatric Patients

| Age | Asymptomatic/Risk-Free | At-Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Birth to 24 months | At 6 months of age | At 6 months of age or as recommended |

| 2–5 years | At 3 years of age | At 3 years of age or as recommended |

| 6–18 years | Before first grade and every 2 years thereafter | Annually or as recommended |

NOTES: AOA states that “[t]he extent to which a child is at risk for the development of eye and vision problems determines the appropriate re-evaluation schedule. Individuals with ocular signs and symptoms require prompt examination. Furthermore, the presence of certain risk factors may necessitate more frequent examinations, based on professional judgement” (AOA, 2002). According to AOA, the factors placing an infant, toddler, or child at significant risk for visual impairment include “prematurity, low birth weight, prolonged supplemental oxygen, or grade III or IV intraventricular hemorrhage; a family history of retinoblastoma, congenital cataracts, or metabolic or genetic disease; infection of mother during pregnancy (e.g., rubella, toxoplasmosis, venereal disease, herpes, cytomegalovirus, or human immunodeficiency virus); difficult or assisted labor, which may be associated with fetal distress or low Apgar scores; high refractive error; strabismus; anisometropia; known or suspected central nervous system dysfunction evidenced by developmental delay, cerebral palsy, dysmorphic features, seizures, or hydrocephalus” (AOA, 2002).

SOURCE: AOA, 2002.

recommend follow-up evaluations for glaucoma patients from every 1 to 2 months to at least once every 12 months, depending on the duration of control of intraocular pressure (IOP), the extent of progression of glaucomatous damage, and whether the patient’s target IOP is reached (AAO, 2015b). By comparison, the frequency of follow-up glaucoma evaluations recommended by AOA varies by patient status and the stability and severity of disease, ranging from weekly or biweekly evaluations for new glaucoma patients or patients with unstable IOP, progressing optic nerve damage, or visual field loss, to once every 6 to 12 months for suspected cases of glaucoma, depending on a particular patient’s risk (AOA, 2011).2

Vision Screening Guidelines

Guidelines specific to vision screenings may also differ and, in some instances, even contradict one another. In a joint policy statement on pediatric vision screenings in community, school, and primary care settings, the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (AAPOS) stated that “routine comprehensive professional eye examinations performed on normal asymptomatic children have no proven medical benefit” (AAO, 2013, p. 3). Instead, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Association of Certified Orthoptists (AACO), AAPOS, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology jointly recommended that pediatricians assess the visual system beginning in infancy and continuing at regular intervals throughout childhood and adolescence. They also suggested that serial visual system screenings in the medical home, using validated techniques, could provide an effective mechanism for the detection and subsequent referral of potentially treatable visual system disorders (AAP et al., 2016). Table 7-3 details the joint pediatric vision screening recommendations.

Conversely, AOA does not generally recommend vision screenings (AOA, 2015d, 2016c). AOA argues that screening is not effective in detecting eye and vision health problems (AOA, 2016c). Moreover, AOA argues

___________________

2 According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology and AOA guidelines on primary open-angle glaucoma, care of patients with glaucoma includes initial and follow-up glaucoma evaluations (AAO, 2015b; AOA, 2011). Initial glaucoma evaluations include many of components of a comprehensive eye examination in addition to procedures or tests specific to diagnosis of glaucoma. For follow-up glaucoma evaluations, the American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines state that evaluation involves “clinical examination of the patient, including optic nerve head assessment (with periodic color stereophotography or computerized imaging of the optic nerve and retinal nerve fiber layer structure) and visual field assessment” (AAO, 2015b, p. 76). AOA guidelines state that follow-up evaluations are similar to the initial evaluation and may include patient history, visual acuity, blood pressure and pulse, biomicroscopy, tonometry, gonioscopy, optic nerve assessment, nerve fiber layer assessment, fundus photography, and automated perimetry, among other procedures (AOA, 2011).

TABLE 7-3 AAP, AAO, AAPOS, and AACO Joint Recommendations on Frequency of Visual System Assessment in Asymptomatic Infants, Children, and Young Adults by Pediatricians

| Assessment | Newborn to 6 Months | 6–12 Months | 1–3 Years | 4–5 Years | 6 Years and Older |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ocular history | X | X | X | X | X |

| External inspection of lids and eyes | X | X | X | X | X |

| Red reflex testing | X | X | X | X | X |

| Pupil examination | X | X | X | X | X |

| Ocular motility assessment | X | X | X | X | |

| Instrument-based screening when available | Xa | X | X | Xb | |

| Visual acuity fixate and follow response | Xc | X | X | ||

| Visual acuity age-appropriate optotype assessment | Xd | X | X |

a AAO recommends instrument-based screening at age 6 months. However, the rate of false-positive results is high for this age group, and the likelihood of ophthalmic intervention is low. A future AAO policy statement will likely reconcile what appears to be a discrepancy.

b Instrument-based screening at any age is suggested if the care provider is unable to test visual acuity monocularly with age-appropriate optotypes.

c The development of fixating on and following a target should occur by 6 months of age; children who do not meet this milestone should be referred.

d Visual acuity screening may be attempted in cooperative 3-year-old children.

SOURCE: AAP et al., 2016.

that vision screening promotes a “false sense of security” and delays treatment for individuals with eye diseases or conditions (AOA, 2016c). Draft guidelines on pediatric eye and vision examination currently available on AOA’s website for comment state that “age-appropriate examination strategies should be used” for infants and toddlers, whereas preschool-age and school-age children are more cooperative with traditional eye and vision tests, although some modifications may still be necessary (AOA, 2016, p. 13). AOA guidelines on the care of patients with amblyopia state that “screening for causes of form deprivation amblyopia should be conducted by the infant’s primary care physician within the first 4 to 6 weeks after birth, and children at risk should be monitored yearly throughout the sensitive developmental period (birth to 6 to 8 years of age)” (AOA, 2004, p. 12). AOA is currently updating its clinical practice guidelines, many of which are almost 15 years old, to better reflect recent research.3 Again, the import of these examples is not to endorse or criticize a particular set of

___________________

3 Personal communication, R. Peele, American Optometric Association, September 6, 2016.

guidelines, but rather to highlight conflicting information available to the public and health care providers.

Lack of guideline consistency is exacerbated by separate guidelines for primary care providers and related evidentiary standards. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) issues evidence-based recommendations that assess the balance of benefits and harms of preventative services provided to asymptomatic patients in a primary care setting or by a primary care clinician (USPSTF, 2016a).4 In 2013, the USPSTF concluded that current evidence “was insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) in adults,” citing the inadequacy of available evidence (USPSTF, 2013).5 USPSTF found no studies that directly evaluated the impact of glaucoma screening on the prevention of visual field loss, vision impairment, or worsened quality of life, nor any direct evidence demonstrating screening-related harm. Evidence on the accuracy of glaucoma screening was inadequate, and the risks of inaccurate diagnosis associated with glaucoma screening were recognized (Moyer, 2013; USPSTF, 2013). Similar conclusions were reached regarding visual acuity screening of asymptomatic adults ages 65 and older (USPSTF, 2016a). The USPSTF concluded that “evidence [was] insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for impaired visual acuity in older adults” (USPSTF, 2016c, p. 908). In particular, although evidence supporting the benefits of early treatment of refractive error, cataracts, and AMD was deemed adequate, three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found no association between visual acuity screening of adults ages 65 and older and improved clinical outcomes (Chou et al., 2016b; USPSTF, 2016c).

In contrast, visual acuity screening by a primary care provider of all children ages 3 to 5 years to detect amblyopia or amblyopia risk factors received a B grade recommendation (USPSTF, 2011). The USPSTF found adequate evidence that the early treatment of amblyopia is associated with improved vision outcomes and that vision screening tools are reasonably

___________________

4 USPSTF recommendations are graded according to the strength of evidence identified by literature review. Grade A recommendations are used when “[t]here is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial.” Grade B recommendations are used when “[t]here is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.” Grade C and D recommendations are used when there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is small or there is evidence of harm or lack of benefit (USPSTF, 2016b). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 permits the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to authorize Medicare coverage of preventative services that receive an A or B grade from the USPSTF. Therefore, although the USPSTF does not account for the cost of a service when assessing its benefits and harms, its recommendations nevertheless have consequences for Medicare payment policy and care access (Lesser et al., 2011).

5 USPSTF I statements are used when “[e]vidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined” (USPSTF, 2016b).

accurate at detecting refractive error, strabismus, and amblyopia. There was limited evidence on the harms of screening. Although a literature review found limited direct evidence supporting the comparative benefit of screening over not screening in pediatric populations, USPSTF noted that good evidence supporting the accuracy of screening methods and the effectiveness of treatments suggests that screening is more likely to lead to improved eye health than no screening (Chou et al., 2011; USPSTF, 2011). USPSTF I statements include information on clinical considerations (e.g., potential preventable burden, potential harm of the intervention, costs, and current practice) in an effort to provide guidance to primary care providers in the absence of a recommendation (Petitti et al., 2009).

Some experts have criticized the USPSTF methodology, especially when rigorous evidentiary standards contribute to the proliferation of I statements that provide limited clinical guidance. For example, Lee (2016) noted that the methodological and financial challenges of conducting an RCT on the impact of visual acuity screening among asymptomatic older adults poses a barrier to the production of evidence that could lead to a conclusive recommendation. Parke and colleagues (2016), commenting on the same recommendation, noted that the review discounted strong evidence on the negative health consequences of vision impairment. Others have noted that the high standards for evidence quality and the narrow focus of questions informing USPSTF literature reviews limit the scope of recommendations and their value as tools to guide clinical decisions (Donahue and Ruben, 2011; Sommer, 2016).

Developing a unified set of evidence-based clinical and rehabilitation guidelines could serve to guide payment policies and address inconsistencies, coverage gaps, and duplicative or wasteful spending. Recent initial attempts by the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, and the American Academy of Optometry to foster such unification through joint educational initiatives or integrated care delivery have highlighted the opportunity for providers to engage one another and promote quality, efficient care (AAO/AAO, 2013; Bailey, 2013).

Assessing the Quality of Guidelines for Eye and Vision Care

In its 2011 report Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust, the IOM highlighted the need for a set of standards that clinical guidelines must meet in order to be trustworthy and serve as a framework for provider decision making (IOM, 2011b). This will require systematic reviews of the evidence, including research question identification, adherence to evidentiary standards, and a compilation of all findings that meets the standard (IOM, 2011a,b). According to the IOM, the evidence should be used to

establish guidelines, which are reviewed and updated every 3 to 5 years (IOM, 2011a). This will require an ongoing commitment to a rigorous evidence-based guideline development process and greater collaboration among professional groups. Box 7-3 includes a list of specific standards from which to assess guideline quality.

Unfortunately, limited research suggests that many existing guidelines, in general, do not meet these standards. For example, a 2012 review of 114 guidelines found that only 49.1 percent met more than half of 18 selected IOM standards (Kung et al., 2012). Other assessment tools, such as the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II instrument, can be used to assess the quality of guidelines in terms of their scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence.6 Several peer-reviewed evaluations of the quality of AAO guidelines are available (Wu et al., 2015a,b,c,d; Young et al., 2015). The committee did not find any similar assessments of AOA guidelines in the published literature. Although the committee was not constituted to evaluate or identify the most effective tools for evaluating guidelines for eye and vision health, it is important that the development of evidence-based guidelines adhere to particular standards, to the extent possible, to ensure robust and comprehensive support for recommended actions.

___________________

6 The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) and AGREE II instruments are frequently used in clinical practice guideline (CPG) evaluations. All CPG evaluations referred to in this report use AGREE or AGREE II. See Brouwers et al. (2010) for a description and comparison of the tools.

The committee acknowledges efforts within the eye and vision field to improve professional guidelines. The American Academy of Ophthalmology and AOA have made efforts to improve and ensure the quality of their respective guidelines. According to Lum and colleagues (2016), the American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines are “based on the best available scientific data as interpreted by panels of knowledgeable physicians and methodologists”—in cases where data are not persuasive, guideline development groups must “rely on both their collective experience and the evaluation of current evidence” (p. 928). The American Academy of Ophthalmology guideline development process includes the identification, limitation, and management of conflicts of interest through an adherence to codes set by the Council of Medical Specialty Societies, and review by several medical societies and relevant patient organizations. The American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines use standardized methods to grade the quality of individual studies, the quality of the body of evidence supporting recommendations, and the strength of recommendations.7 Barring revisions, the American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines are valid for 5 years after their release date (AAO, 2016e). As of May 2016, 22 AAO Preferred Practice Pattern® guidelines were listed on the AAO website (AAO, 2016a).

AOA has developed 18 consensus-based guidelines and two evidence-based guidelines, Eye Care of the Patient with Diabetes Mellitus, and the Comprehensive Adult Eye and Vision Examination (AOA, 2014, 2015d).8 AOA has created a 14-step process for developing evidence-based guidelines and states that its Evidence-Based Optometry Committee is revising optometric guidelines in response to the IOM standards for trustworthy guidelines (AOA, 2015c, 2016a). AOA evidence-based guidelines use scales to grade the strength of evidence and recommendations and offer a guideline development process that includes steps to manage conflicts of interest and allow for peer and public review (AOA, 2014, 2015d).9 AOA evidence-based guidelines state that the guidelines should be revised every 2 to 5 years (AOA, 2014, 2015d). Unfortunately, statements in AOA consensus-

___________________

7 AAO uses the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation methods for grading evidence quality and recommendation strength. For details, see the Methods and Key to Ratings section of an AAO Preferred Practice Pattern guideline.

8 At the time of writing, a third clinical practice guideline (Comprehensive Pediatric Eye and Vision Examination) was under revision, and a draft version of the document was available for peer and public review.

9 The evidence and recommendation grading tools as described in the AOA evidence-based guidelines on Eye Care of the Patient with Diabetes Mellitus and on Comprehensive Adult Eye and Vision Examination are not identical. For details, see the How to Use This Guideline sections of these guidelines.

based guidelines, such as the guidelines on Pediatric Eye and Vision Examination, do not always provide information on the graded strength of this evidence or of the statements it supports (AOA, 2002). Similarly, the AOA consensus guidelines on Pediatric Eye and Vision Examination do not include information on the guideline development process, including methods of literature review, management of conflicts of interest, or external review (AOA, 2002). AOA consensus-based guidelines, such as the guidelines on Pediatric Eye and Vision Examination, state that the guidelines will be reviewed periodically and revised as needed (AOA, 2002).10

Improving the Consistency of Eye and Vision Care Guidelines

Coming to consensus on recommended care is critical to create clear messaging that targets both patients and non–eye care providers about the need for regular eye care services. From a population health perspective, prioritizations for guideline development should be influenced by the number of people affected, the severity and reversibility of vision loss that can occur, the diversity with which the condition is currently managed, the number of health care professionals who typically engage with patients about a specific disease or condition, and the breadth of the literature currently available. This might be of most relevance for guidance on the frequency of eye examinations and may be supported by federal guidance on what factors (e.g., frequency, severity, preventability, treatability, difference between current and optimal practice) should be used in consensus-based and evidence-based recommendations.

A collaborative and inclusive working group would be useful to establish a single set of guidelines that are coherent, comprehensive, and clear about what services are required at what intervals, and how best to connect patients to necessary follow-up care. The process for conducting a systematic review of existing evidence and distilling guidelines from that evidence is a lengthy process, and collaboration throughout the eye and vision care field (including federal and state governmental entities that focus on eye and vision health) will be paramount. This collaborative process can also help identify research gaps to promote a shared research agenda.

___________________

10 The AOA consensus-based guideline on Care of the Patient with Learning Related Vision Problems states that the guideline “will be reviewed periodically” (AOA, 2008, p. ii). All other consensus-based guidelines state that the guideline will be “will be reviewed periodically and revised as needed.”

ASSESSING QUALITY AND IMPROVEMENT INITIATIVES

Focusing on quality improvement as an overarching goal can help standardize and promote high-quality care; in turn, high-quality care can address factors that contribute to poor and inequitable eye and vision health care. Continuous quality improvement (CQI) is a “process-based, data-driven approach to improving the quality of a product or service through iterative cycles of action and evaluation” (RWJF, 2012, p. 1). Rather than a short-term, single-issue quality improvement and assurance initiative, CQI focuses on correcting the root causes of systemic issues through an iterative quality improvement process. This process complements the public health wheel (see Chapter 1), which depicts population health as an iterative process of assessment, policy development, and assurance.

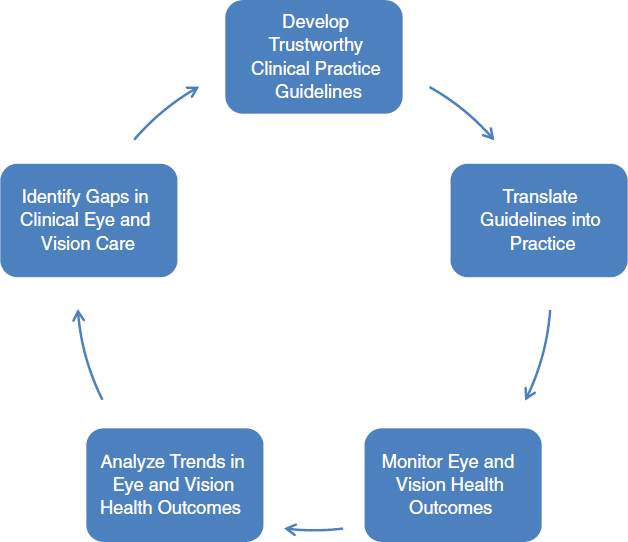

Figure 7-1 presents a common CQI framework adapted for eye and vision care. In this figure, the CQI process is a five-step process: guideline development, practice change, performance monitoring, surveillance and data analysis, and identification of opportunities for improvement. An adherence to established guidelines provides the baseline from which to

SOURCE: Adapted from Kneib, 2009.

measure impact on health outcomes and improvement over time. Development of evidence-based guidelines requires sufficient research and data. The rapid and accurate translation of guidelines into daily practice may require the development and provision of educational materials and training programs informed by translational and implementation science. Tracking patient outcomes and process and performance measures of the health care system requires a broad set of surveillance and monitoring tools, including electronic health records (EHRs). Data analysis may require the expertise of statisticians, epidemiologists, health informaticians, and other public health and quality improvement specialists. Identifying opportunities for improved patient outcomes and health care system performance can then inform revisions of evidence-based guidelines, which can help accelerate policy changes that better support eye and vision health.

An effective CQI process requires organizational champions and committed leadership. A number of government agencies, educational organizations, and professional groups are involved in CQI activities or efforts that could facilitate a CQI process, to improve the quality of eye and vision care. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) is one of a number of agencies and organizations that provide guidance and tools to help stakeholders design, implement, sustain, and spread quality improvement within a health care system (HRSA, 2011). Toolkits have been developed to promote CQI in eye and vision health (Brien Holden Vision Institute, 2016). AOA and the American Academy of Ophthalmology have launched patient registries as part of larger quality improvement efforts (AAO, 2016b; AOA, 2015b).11 Patient registries can promote improvements in care quality by enabling providers to assess the effectiveness of treatment, analyze their performance for improvement opportunities, and monitor patient outcomes. Data from patient registries may also be used to inform policy, monitor the effectiveness of treatments across populations, and identify public health issues (Kent, 2015). The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has employed its Quality Enhancement Research Initiative to identify opportunities for improving eye care and preventing vision loss among veterans with diabetes (Krein et al., 2008). The Diabetes Recognition Program of the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) recognizes physicians for complying with diabetes care quality measures, which include the appropriate referral of diabetic patients for eye examination (NCQA, 2016b). In January 2016, HRSA announced a funding opportunity for rural providers to participate in a Small Health Care Provider Quality Improvement Program, and it listed eye exams for diabetic patients as an optional quality measure (HRSA, 2016b). Although evidence

___________________

11 See Chapter 4 for further detail on the AOA and American Academy of Ophthalmology registries.

on the impact of these efforts and programs on eye care quality and patient outcomes is limited, their existence points to an increased emphasis on CQI in eye and vision care. These efforts can be used as a foundation from which to implement subsequent CQI initiatives.

Quality improvement is also being explicitly built into grants that support eye and vision health in communities. For example, the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality has partnered with the National Center for Children’s Vision & Eye Health at Prevent Blindness on a 3-year, HRSA-funded project to support the development of comprehensive and coordinated approaches to children’s vision and eye health in five states (NICHQ, 2015). The project will employ quality improvement (QI) principles and practices to strengthen statewide partnerships and stakeholder coordination, increase accessibility of eye care in remote communities, increase early detection and treatment of eye diseases, establish state-level surveillance, and implement accountability measures (NICHQ, 2015). As more eye and vision professionals participate in accountable care organizations or other pay-for-performance initiatives in the value-driven health care landscape, CQI will play an increasingly important role in clinical eye and vision care.

A number of organizations, including the National Quality Forum (NQF), Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement, NCQA, and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, have identified and developed, or evaluated and endorsed, quality improvement measures and metrics that can be used for CQI activities (AHRQ, 2016a; AMA, 2016; NCQA, 2016a; NQF, 2016c). The NQF has endorsed several quality measures related to counseling and eye examinations for patients with AMD, eye examination and follow-up care for patients with diabetic retinopathy, examination of the optic nerve head and treatment outcomes for patients with glaucoma, and complications and outcomes after cataract surgery.12 Unfortunately, NQF has not endorsed—and the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse does not list—other measures related to eye and vision care, including those pertaining to vision screening and the subsequent referral and follow-up of adult patients, referral to vision rehabilitation and support services for patients with irreversible vision impairment, correction of identified

___________________

12 NQF-endorsed, eye care–related quality measures include Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Optic Nerve Evaluation (NQF-0086); Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Dilated Macular Examination (NQF-0087); Diabetic Retinopathy: Documentation of Presence or Absence of Macular Edema and Level of Severity of Retinopathy (NQF-0088); Diabetic Retinopathy: Communication with the Physician Managing Ongoing Diabetes Care (NQF-0089); Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Reduction of Intraocular Pressure by 15% or Documentation of a Plan of Care (NQF-0563); Cataracts: Complications Within 30 Days Following Cataract Surgery Requiring Additional Surgical Procedures (NQF-0564); Cataracts: 20/40 or Better Visual Acuity Within 90 Days Following Cataract Surgery (NQF-0565); and Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Counseling on Antioxidant Supplement (NQF-0566).

refractive error, or patient counseling on modifiable risk factors for eye disease. To support the CQI process, research to build the evidence base informing these and other quality these measures will need to be pursued.

Pursuing a CQI research agenda will require collaboration among investigators working in multiple areas, as well as the dedication of funding, tools, and facilities. It will also require a population health surveillance system capable of collecting data on myriad facets of the vision care system and the populations and communities it serves (see Chapter 4). These surveillance data are necessary for the implementation of a successful CQI program to improve the performance of the vision care system.

PROMOTING DIAGNOSIS AND FOLLOW-UP CARE TRANSITIONS THROUGH INTEGRATION

Identifying who needs what care at what time is only part of the equation to promoting appropriate eye care. In many cases, especially in the context of vision screening, additional follow-up care will be necessary to provide prescription lenses or other types of clinical treatments or monitoring. Despite advances in the clinical treatments for major eye diseases that have dramatically improved population eye and vision health, many barriers to care delivery remain. Structural separations between optometry, ophthalmology, and primary care may contribute to inconsistent referral practices, poor communication, inappropriate or delayed referrals, and interruptions in care continuity, as reported in studies assessing the state of primary care–specialty referrals (Mehrotra et al., 2011; Wiggins et al., 2013). The integration of primary care and eye and vision care, as modeled in the patient-centered medical home and accountable care organizations, holds potential as a strategy for improving coordination and communication between providers in primary care and those in eye and vision care. EHRs and other health informatics tools can contribute to integration by enabling secure data sharing among providers.

Referrals Within and Across Professional Lines

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), collaborative practice occurs when “multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds provide comprehensive services by working with patients, their families, caregivers, and communities to deliver the highest quality of care across settings” (WHO, 2010, p. 13). Beyond simply raising public awareness about the roles, competencies, and services of eye and vision care professionals and ensuring an adequate workforce to meet patient needs (see Chapter 6), it is important to recognize that eye and vision health is the domain of all types of health care providers. For example, eye and

vision care providers can help identify risk factors as well as detect and help manage many chronic diseases. For example, comprehensive dilated eye exams can detect retinal vascular changes that may suggest hypertension or diabetes, reveal cholesterol plaques within retinal arteries that indicate risk of stroke, and detect tumors, among other things (Chous and Knabel, 2014). Similarly, by providing vision screenings and referring patients as appropriate to eye and vision care providers, primary care providers can help identify potentially vision-threatening problems and refer patients to an ophthalmologist or optometrist for a comprehensive eye examination to make a definitive diagnosis, establishing productive and ongoing professional relationships. An investigation of the referral patterns of 136 family physicians found that referrals to ophthalmologists were more likely than referrals to other medical specialties to result in long-term (as compared to short-term) referrals or consultations and in the transfer of patient management (Starfield et al., 2002). However, the study also found that family physicians referred patients with diabetes to ophthalmologists in only 27 of 56 cases, with remaining referrals directed primarily to endocrinologists and nutritionists.

Eye and vision health is also relevant to health care providers beyond primary care physicians. Often, vision impairment is a manifestation or consequence of a disease that requires the expertise of other health care specialists involved in the coordination of care. For example, visual impairment is a key symptom of multiple sclerosis (Balcer et al., 2015). The American Academy of Neurology’s current practice parameter on the diagnostic assessment of children with cerebral palsy notes that vision impairment and disorders of ocular motility occur in 28 percent of children with cerebral palsy and recommends that this patient population receive vision screenings (Ashwal et al., 2004). Endocrinology is another specialty that frequently intersects with vision care, particularly in diabetes management.

Physician assistants and nurse practitioners provide at least 11 percent of all outpatient medical services in the United States, and are more likely to practice in rural areas than primary care physicians (16 percent versus 11 percent) (AHRQ, 2014a; Hooker and Everett, 2012). The inclusion of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in patient care is associated with decreased health care costs, higher-quality care, and improved patient outcomes (Hooker and Everett, 2012; Reuben et al., 2013; Roblin et al., 2004). However, research indicates that nurse practitioners or physician assistants seldom practice in ophthalmology. The 2013 Annual Survey Report of the American Academy of Physician Assistants found that only 10 out of 15,798 responding physician assistants worked in ophthalmology as a primary specialty (AAPA, 2014). A report by the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) on nurse practitioner practice environments did not include ophthalmology as a subspecialty in which nurse practitioners actively

practiced (AANP, 2015). In addition, specialty certification and postgraduate training focused on ophthalmology is not available for nurse practitioners or physician assistants. The AANP Certification Program does not offer certification in ophthalmic care (AANPCP, 2016). The National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants offers specialty certifications, but not in ophthalmology (NCCPA, 2016). The Association of Postgraduate Physician Assistant Programs compiles a list of current postgraduate programs; although none of these programs focuses specifically on ophthalmology, several programs include clinical or surgical rotations in ophthalmology (APPAP, 2016).13 For registered nurses specializing in ophthalmic care, certification through the National Certifying Board for Ophthalmic Registered Nurses is available but not required (ASORN, 2016).

Unfortunately, referrals to ophthalmologists and optometrists from other health care professionals remain suboptimal, for various reasons. Holley and Lee (2010) interviewed focus groups of nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and rural and academic primary care physicians in order to identify barriers to referring patients to eye care. The three most commonly cited barriers were “no/little feedback from eye care providers” (27.5 percent of comments), followed by “patient’s lack of finances/insurance coverage” (25.5 percent), and “difficulty in scheduling ophthalmology appointments” (15.7 percent) (p. 1867).14 The most common suggestions for improving referral to eye care involved implementing shared electronic medical records (26.5 percent of comments), improving eye care provider communication and feedback (22.4 percent), and having ophthalmologists in primary care clinics on an intermittent basis (18.4 percent) (Holley and Lee, 2010).15 Thus, there is an opportunity for both eye care professionals and the medical establishment to capitalize on shared interests and concern for patients. By considering referrals to be part of whole patient care, health care providers contribute to practices that may lead to improvements across multiple measures of health.

___________________

13 The Emergency Medicine physician assistant (PA) residency at Johns Hopkins University, the PA Postgraduate Fellowship in Emergency Medicine at Albany Medical Center, the Emergency Medicine PA Residency at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Fresno, the Surgery Physician Assistant Fellowship at the Texas Children’s Hospital, and the Emergency Medicine PA/Nurse Practitioner (NP) Residency Program at Yale New Haven Hospital all include clinical or surgical rotations in ophthalmology (APPAP, 2016).

14 Percentages are calculated. Out of 51 total comments, 14 were categorized as “No/little feedback from eye care providers” [(14/51) × 100 = 27.5 percent], 13 were categorized as “Patient’s lack of finances/insurance coverage” [(13/51) × 100 = 25.5 percent], and 8 were categorized as “Difficulty in scheduling ophthalmology appointment” [(8/51) × 100 = 15.7 percent].

15 Percentages are calculated. Out of 49 total comments, 13 were categorized as “Implement electronic medical records” [(13/49) × 100 = 26.5 percent], 11 were categorized as “Better communication/feedback from ECPs” [(11/49) × 100 = 22.4 percent], and 9 were categorized as “Have ophthalmologists in primary care clinic on certain days” [(9/49) × 100 = 18.4 percent].

Models of Integrated Eye and Vision Care in the United States

Integrated models of care improve efficiencies within the medical establishment to facilitate coordinated, patient-centered care across multiple providers in a time when the increasing prevalence of chronic conditions, such as chronic vision impairment, and age-related diseases require more value-conscious health care systems. For purposes of this report, the term “integrated care” refers to any model of care designed to promote collaborative practice for the purposes of improving eye and vision care access and quality.

Unfortunately, the research on the distribution, frequency, cost, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of models of integrated vision care in the United States is limited. A number of studies have documented international efforts to improve referral patterns between general practitioners, ophthalmologists, and optometrists and to implement referral-only diagnostic services for patients with common eye diseases in order to improve the referral process and reduce costs and patient load on secondary and tertiary services. These efforts have met with some success (Bourne et al., 2010; Jamous et al., 2015; Mandalos et al., 2012; Voyatzis et al., 2014). Several of these studies have highlighted the need for new or additional training to effectively implement referral centers. Although these studies can be instructional in identifying factors to consider when designing interventions within the United States, they have limited applicability in the United States because of the differences in how health care systems are structured.

Several recent international investigations have highlighted the success of integrated care models at decreasing the costs of health care, increasing the efficiency of health systems, and improving patient outcomes. For example, an RTC conducted in the Netherlands compared different methods of monitoring glaucoma patients and found that eye care provided to stable glaucoma patients and patients at risk of glaucoma by ophthalmic technicians and optometrists working in hospital-based glaucoma follow-up units was equal in quality and lower in cost than care provided by hospital-based residents and ophthalmologists specializing in glaucoma care (Holtzer-Goor et al., 2010).16 Compared to monitoring of stable glaucoma patients and patients at-risk of glaucoma by glaucoma specialists (i.e., ophthalmologists specializing in glaucoma) and residents, monitoring of these patients by a

___________________

16 Care quality was measured in terms of provider compliance to a predetermined care protocol; multiple indicators of patient satisfaction; the stability of the patient according to practitioner, as measured by changes in the duration of intervals between patient visits; difference between IOP at baseline and at study conclusion; examination results; and the number of treatment changes. There were no statistically significant differences between the care provided by glaucoma specialists or residents and the care provided by optometrists and ophthalmic technicians for any of the care quality measures. Patients randomized to receive care from the glaucoma follow-up unit were seen by an ophthalmologist every third visit, or sooner if necessary.

glaucoma follow-up unit staffed by optometrists and ophthalmic technicians was associated with a high probability of reduced costs of care to the patient (78 percent probability of reduced costs of care), to the hospital (98 percent probability of reduced costs of care), to the health care system (87 percent probability of reduced costs of care), and to society as a whole (84 percent to 89 percent probability of reduced costs of care) (Holtzer-Goor et al., 2010). A subsequent study of the same integrated care model found that care provided in the glaucoma follow-up unit adhered closely to treatment protocols and was preferred by patients (Holtzer-Goor et al., 2016).

A study performed in Belgium compared the efficiency and efficacy of “lean” care pathways for cataract surgery and perioperative care, where the management of uncomplicated cases was shared by ophthalmologists, optometrists, and nurses, to the efficiency and efficacy of traditional pathways, where ophthalmologists managed nearly all elements of care (van Vliet et al., 2010). In the traditional care pathway, the eye examination and pre-assessment (e.g., health check, patient-reported medical history) were performed during separate patient visits to the hospital, and the formulation of the surgical care plan and the next-day post-surgery review required visits by all patients. In the “lean” care pathway, the eye examination and pre-assessment were performed in a single patient visit to the hospital, and the formulation of the surgical plan and next-day post-surgery review did not require patient visits in cases where ocular comorbidities and perioperative complications were not present. The minimum number of patient visits to the hospital decreased from five in the traditional care pathway to three in the lean care pathway. Compared to patients in the traditional pathway, those in the “lean” care pathway required on average significantly fewer hospital visits. Compared to the traditional care pathway, the “lean” care pathway also allowed ophthalmologists to treat significantly more patients in the same amount of time, and the authors suggest that further gains in efficiency might be achieved through greater adherence to the design of the “lean” care pathway (van Vliet et al., 2010).

In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service’s Chronic Eye Care Services Programme supported eight pilot projects that sought to improve care pathways for the treatment of glaucoma, AMD, and vision impairment through better integration of the eye care workforce (McLeod et al., 2006). Together, these findings suggest that the integration of clinical eye and vision care services holds promise for lowering costs, improving patient satisfaction, promoting adherence to guidelines, and ensuring efficient and effective care. It is important to note that while these studies can serve as examples, they may have limited applicability to the U.S. system because of differences in the health care systems, in the scopes of practices of eye care providers, and in the patient populations in these countries compared to those in the United States. The committee was unable to identify

peer-reviewed studies that described how U.S.-based integrated optometrist-ophthalmologist models are organized or operated, their associated costs and cost-effectiveness, or their impact on eye and vision health care and patient outcomes. Existing articles in trade publications only acknowledge that these models exist and are viable from a business perspective, although evidence supporting these claims may be insufficient. This is a much needed area of research. One potential strategy for developing an evidence base would be to conduct demonstration projects testing different models of eye and vision care organization, operation, and payment.

Incorporating Vision and Eye Health into Emerging Medical Models of Care

According to the American College of Physicians, the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) is a “care delivery model whereby patient treatment is coordinated through their primary care physician to ensure they receive the necessary care when and where they need it, in a manner they can understand” (ACP, 2016). The model emphasizes services that are comprehensive, patient-centered, coordinated, accessible, safe, and of high quality (AHRQ, 2016b). A review of peer-reviewed studies, government reports, industry studies, and independent federal program evaluations found that PCMH programs have been associated with reductions in cost and in the unnecessary use of health care services, and may also lead to improvements in patient satisfaction, quality-of-care metrics, and access to primary care services (Nielsen et al., 2016). Examples of PCMH programs that have resulted in improved patient health and care quality, reduced readmissions rates, reduced care costs, and/or short-term return on investments include the New York-Presbyterian Regional Health Collaborative, the Pennsylvania Chronic Care Initiative, and Illinois Medicaid’s Illinois Health Connect and Your Healthcare Plus program (Carrillo et al., 2014; Friedberg et al., 2014; Phillips et al., 2014).

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has developed a unique PCMH model called the Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT). The provider team includes a primary care provider, a nurse care manager, a clinical associate, and an administrative clerk. Specialty care, including vision care, is provided through referral (VA, 2016). Studies of the PACT program suggest that PACT implementation is associated with significant improvements in the proportion of acute care patients contacted within 2 days of hospital discharge (Werner et al., 2014). PACT implementation has also been associated with a significant increase in the overall rate of telephone-based encounters between providers and patients, in the proportion of patients seen within 7 days of desired appointment date, and in the proportion of same day appointment requests accommodated (Rosland et al.,

2013). Among 913 VHA primary care clinics, greater progress in the PACT implementation process was associated with higher patient satisfaction, lower staff burnout rates, lower hospital admission rates for some ambulatory conditions, lower emergency department usage rates, and improved performance on 41 of 48 clinical quality measures (Nelson et al., 2014).

Despite the success of PACT and other PCMH models at reducing health care costs and improving some measures of care quality and access, it is not clear what impact these models have had on eye health, as research on the impact of the PCMH model on eye care is limited. However, studies on the impact of the PCMH model on comprehensive diabetes care—a component of which is annual dilated eye exams—can provide clues to the quality of eye care received within a PCMH. Kern and colleagues (2014) compared quality of patient care provided by physicians practicing in PCMHs established over the course of a 3-year study to that provided by physicians not practicing in a PCMH and who used either paper-based patient health records or an EHR. Quality of care was assessed using 10 quality measures, including provision of dilated eye examinations for patients with diabetes. At baseline, no significant differences in the percentage of patients with diabetes who were receiving dilated eye examinations existed between groups. By the end of the study, the proportion of patients with diabetes receiving dilated eye examinations was significantly higher among those receiving care from physicians practicing in a PCMH compared to those receiving care from physicians not practicing in a PCMH. Over the course of the study, performance on the dilated eye examination quality measure was 3–4 percent higher for physicians practicing in PCMHs than for physicians not practicing in PCMHs (Kern et al., 2014). A follow-up study found that although the overall care quality was similar between physician groups, patients with diabetes who were receiving care from physicians in PCMHs were still more likely to have eye exams than patients with diabetes who were receiving care from other physicians (Kern et al., 2016). Another study found that diabetic patients of primary care physicians who did not formally practice within a PCMH but who adhered closely to key features of the PCMH model were more likely to have received an eye exam in the previous year than diabetic patients of primary care physicians who adhered less closely to the PCMH model (Stevens et al., 2014).17 These studies demonstrate the positive impact of the PMCH model of care on the provision of diabetic eye exams, and suggest the possibility that the PCMH model’s emphasis on coordinated, team-based care

___________________

17 Physician adherence to features of PCMH was based on patient responses to the Primary Care Assessment Tools (PCAT) Adult Expanded. A one-point increase in a physician’s overall PCAT score was associated with 1.88 higher odds of his or her patients having received an eye exam in the previous year (Stevens et al., 2014).

that is comprehensive, patient-centered, and high-quality could also benefit other aspects of eye care.

The PCMH model may not always promote the quality of eye and vision care. Among a core set of clinical quality measures recommended by the Patient-Centered Medical Home Evaluators’ Collaborative for evaluating and comparing the effectiveness of PCMH programs, the sole vision-related measure was the percentage of patients ages 18 to 75 with type 1 or 2 diabetes who received a retinal eye exam as a component of comprehensive diabetes care (Rosenthal et al., 2012).18 The 2014 Standards and Guidelines for NCQA’s Patient-Centered Medical Home, which provide guidance for assessing the quality of care offered by practices using the PCMH model, do not explicitly require the collection of vision-related clinical data, the inclusion of vision-specific components within the patient health assessment, or the use of vision screenings except where recommended by major public health agencies or organizations (NCQA, 2014b). Thus, while the PCMH model of care represents an opportunity for improved integration of eye and primary care, the inclusion of more eye care services and additional eye care professionals on the team should be studied to determine how it would affect the quality of eye and vision care in PCMH programs.

Providing high-quality, accessible, and patient-centered care requires coordination between primary care providers practicing in the PCMH and clinical and nonclinical providers and services operating outside the medical home.19 The concept of the “medical neighborhood” was developed to account for the role that this broader set of services plays in achieving the goals of the PMCH, and the NCQA Patient-Centered Specialty Practice (PCSP) Recognition Program was developed to recognize and support specialty practices that seek to improve the quality of specialty care through coordination with primary care, performance measurement, and

___________________

18 In addition to the core set of clinical quality measures, the collaborative also recommended that PCMH program evaluators select a group of clinical quality measures from a list that included measures related to adolescent well-child visits, well-child visits in the first 15 months of life, and well-child visits in the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth years of life. American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines require eye care to be included as part of the physical exam component of these visits (AAP, 2008a,b,c).

19 AHRQ has conceived the medical neighborhood as a “PCMH and the constellation of other clinicians providing health care services to patients within it, along with community and social service organizations and State and local public health agencies” (AHRQ, 2011, p. 5). NCQA has identified specialty practices, accountable care organizations, behavioral health, public health, work site and retail clinics, and pharmacies as members of the medical neighborhood (NCQA, 2014a).

other means (Fisher, 2008; Huang and Rosenthal, 2014; NCQA, 2016d).20 Ophthalmologists, but not optometrists, are eligible to participate in the PCSP Recognition Program (NCQA, 2016c).21 Excluding optometrists from participating in the PCSP program may eliminate the contribution of a critical cohort of eye care providers and may limit the degree to which eye and vision care can be easily incorporated into specific PCMH models and medical neighborhoods.

Accountable care organizations (ACOs) offer another path to integration of primary care and specialty medical services. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) describes ACOs as “groups of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers, who come together voluntarily to give coordinated high quality care” (CMS, 2015b). Initiatives such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program and the Pioneer and Next Generation ACO Models seek to improve the quality of patient care while lowering health care costs (CMS, 2015c,d, 2016b). Achieving these twin goals may require extensive data sharing, transitioning to value-based payment policies, using quality measures to monitor provider performance and patient outcomes, and the coordination of providers and services, among other strategies.

The fact that there is a limited amount of research on the impacts of ACOs on eye and vision health may in part be the consequence of limitations in the reporting requirements for ACOs. ACOs participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program are required to report quality data, and they must meet established quality performance standards set by CMS in order to be eligible to receive shared savings (CMS, 2016a). Since performance year 2012, quality measures related to diabetes care have been included among the quality performance measures CMS requires ACOs to report; however, a measure related to the provision of diabetic eye exams was not included among these until performance year 2015 (CMS, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015a, 2016a). For performance years 2015 and 2016, ACO performance on the provision of diabetic eye exams will be reported as a composite measure with ACO performance on control of hemoglobin A1c

___________________

20 The objectives of the PCSP Recognition Program are to enhance coordination between primary care and specialty care, strengthen relationships between primary care clinicians and clinicians outside the primary care specialties, improve the experience of patients accessing specialty care, align requirements with processes demonstrated to improve quality and eliminate waste, encourage practices to use performance measurement and results to drive improvement; and identify requirements appropriate for various specialty practices seeking recognition for excellent care integration within the medical home (NCQA, 2016e).

21 Other clinicians who are eligible to participate in the PCSP Recognition Program include nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and certified nurse midwives, as well as doctoral or master’s-level psychologists, social workers, and marriage and family counselors who are state licensed or certified (NCQA, 2016c).

levels among diabetic patients.22 Data for ACO performance on this composite measure were not available at the time of writing. The addition of eye care–related quality measures to the set of measures that CMS requires ACOs to report could provide useful data on how ACOs affect eye care quality and access.

As the population ages, and chronic eye disease and other vision problems become increasingly prevalent, demand for models of care capable of meeting national eye and vision health needs will continue to grow. More research is needed to understand how the medical field can work as a cohesive and coordinated unit, achieving better value and health outcomes. For example, it is important to determine how PCMHs, ACOs, and other integrated models of care that promote collaborative practice—as well as the policies that inform their organization, adoption, and performance monitoring and quality improvement activities—can be adapted to best meet current and future eye and vision health needs. Strategies and actions to better support integration of clinical eye and vision services with vision rehabilitation, social services, public health departments, and other stakeholders are also needed. More health services research and evaluation of existing programs will be essential to guide these efforts.

Role of Health Informatics

Advances in health information technology, particularly the implementation of EHRs, have the potential to optimize care delivery, enhance quality and safety in a number of ways, and ultimately improve patient outcomes (Blumenthal and Tavenner, 2010). Implementing EHR systems can ensure that providers have access to up-to-date, relevant clinical patient information at the point of care (Chiang et al., 2011). It can also facilitate information exchange across care settings, thereby improving communication and coordination between primary care providers and eye care providers (e.g., optometrists, ophthalmologists) or other specialists treating comorbidities. This would theoretically reduce the duplication of various laboratory tests or imaging and lessen the risk of treatment errors. The data in EHRs can also be used to prioritize, justify, and analyze public health activities by identifying and tracking eye disease and vision impairment—and interventions to prevent and reduce the same—at the population level.

___________________

22 CMS-required quality performance measures on diabetic eye exams and control of hemoglobin A1c levels are based on NQF-endorsed quality measures. NQF-0055: “The percentage of members 18 to 75 years of age with diabetes (type 1 and type 2) who had an eye exam (retinal) performed” (NQF, 2016a). NQF-0059: “The percentage of patients 18–75 years of age with diabetes (type 1 and type 2) whose most recent HbA1c level during the measurement year was greater than 9.0% (poor control) or was missing a result, or if an HbA1c test was not done during the measurement year” (NQF, 2016b).

For this reason, EHRs can be powerful tools for informing public health practice and improving public health.

EHR use has grown considerably in recent years. From 2001 to 2014 the proportion of office-based physicians who used any type of EHR system increased from 18.0 percent to 82.8 percent, and the proportion of office-based physicians who reported having an EHR system that met the criteria for a basic EHR system increased significantly from 11.0 percent in 2006 to 50.5 percent in 2014 (CDC, 2015; Hsiao, 2014).23 However, EHR use among ophthalmologists is low compared with most other medical specialties, with only 15.0 percent and 34.7 percent of ophthalmologists reporting EHR use in 2003 and 2010, respectively, compared with 13.7 percent and 64.2 percent in 2003 and 2010 for general or family medicine. In multivariate analysis, ophthalmologists had lower odds of using EHRs than any other of 13 specialties except psychiatry and dermatology (Kokkonen et al., 2013). A 2012 survey of 492 ophthalmologists found that 32 percent of ophthalmology practices in the United States had adopted EHR systems, and another 31 percent planned to do so within 2 years (Boland et al., 2013). A 2015 survey by AOA found that 17 percent and 49 percent of responding optometrists planned to achieve criteria for, respectively, stage 1 and stage 2 meaningful use in 2015. The survey also found that 66 percent of responding optometrists used complete EHRs, as defined by the AOA (AOA, 2015a).24 Adoption among both groups is increasing: EHR adoption among surveyed ophthalmologists doubled from 2007 to 2011 and increased by 3 percent from 2014 to 2015 among surveyed optometrists (AOA, 2015a; Boland et al., 2013).

The adoption of EHRs by eye care specialists may be impeded by concerns about its effects on the quality of clinical documentation. Sanders and colleagues (2013) compared the effects of a paper-based health record system to those of an EHR system on the clinical documentation habits of ophthalmologists assessing patients with AMD, glaucoma, and pigmented choroidal lesions. For all three diseases, the paper-based system was associated with significantly fewer complete examination findings and critical

___________________

23 According to Hsiao (2014), a basic EHR system is one that has each of the following features: “patient history and demographics, patient problem lists, physician clinical notes, [a] comprehensive list of patients’ medications and allergies, computerized orders for prescriptions, and [the] ability to view laboratory and imaging results electronically.”

24 Complete EHRs were defined as those that included both practice management and patient health information systems. Practice management systems were defined as “electronic software packages that track and maintain information such as: patient demographics, scheduling, billing, insurance, and recall.” Patient health information systems were defined as “electronic software packages that maintain health information such as: exam data, testing, images and prescriptions” (AOA, 2015a, p. 1).