9

Eye and Vision Health:

Recommendations and a Path to Action

The long-term goal of a population health approach for eye and vision health would be to transform vision impairment from an exceedingly common to a rare condition, at the same time reducing the associated health inequities. A population health approach comprises multiple actors who work separately and cooperatively to influence multiple determinants of health. These collaborations also allow governmental public health entities to fulfill their core functions: assessment (i.e., monitoring communities to identify and characterize public health needs and priorities); policy development (i.e., the use of scientific evidence to guide decisions about, and the design and implementation of, actions and policies that address population health issues); and assurance (i.e., ensuring that stakeholders have the resources necessary to achieve established process and outcome goals) (IOM, 1988). However, as discussed in Chapter 5, implementing population-level improvements is the responsibility of the entire population health system, including all the healthy system’s stakeholders. Figure 5-1 in particular highlighted the relevant partners that are critical to the effort of advancing population health objectives, including the community, other government agencies, the education sector, nonprofit organizations, the media, employers and businesses, and the clinical care system.

There are steps that can be taken right now to significantly reduce the burden of vision impairment within the next few years, based on current knowledge and available treatments. To ensure that populations, especially underserved and at-risk populations, know to seek and have access to timely and high-quality eye and vision care, coordinated efforts are needed to expand the footprint of eye care and vision services beyond the offices

of eye and vision care providers. There are also actions that individuals and communities can take to create social and built environments that actively and passively promote healthy eye behaviors.

But current knowledge is not enough to produce optimal eye and vision health. At present, there is no long-term investment in surveillance and research to identify the most at-risk populations, associated risk and protective factors, cost-effective treatments, and efficient health care and public health system models to expand access to care. Moreover, the emphasis in eye and vision care research has shifted away from more population-based studies that focus on the translation of clinical research into effective practice and the evaluation of specific interventions and programs to promote population health to research that focuses on the pathophysiology of disease and new treatments. While this is an important aspect of biomedical research, it must be balanced against the need for interventions that have a larger population health impact.

Achieving the twin goals of improving eye and vision health and increasing health equity will require progress along multiple fronts and, in particular, national and state efforts to ensure that resources and knowledge are available and communicated to help implement actions within communities. A population health strategy to promote eye and vision health will have many layered components that influence behaviors across the human lifespan and policies and environments across an array of topics and settings. Some components will target changes that require minimal investment, such as wearing sunglasses or protective eyewear in hazardous work environments or certain recreational activities. Other changes will require sustained support from extensive partnerships that capitalize on the different strengths of the public and private sectors. Developing support for the policies, programs, and resources to generate these changes at the federal, state, and local levels will necessitate a different mindset about the role of eye and vision health promotion in daily activities and formal prioritization in national, state, and local population health strategic goals and programs.

This chapter presents a roadmap to advancing eye health. In particular, it proposes recommendations that represent key steps along the path to optimal eye and vision health of populations and to the long-term functionality of those with vision impairment. This chapter concludes by providing examples of the types of activities that different stakeholders can pursue. The examples flow from the committee’s recommendations to advance sustained progress toward a culture of eye and vision health.

TRANSLATING A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK INTO ACTION: RECOMMENDATIONS

In its statement of task, the committee was asked to “examine the core principles and public health strategies to reduce visual impairment and promote eye health in the United States,” including short- and long-term strategies to prioritize eye and vision health through collaborative actions across a variety of topics, settings, and different sectors of communities and levels of government (see Box 1-1, Chapter 1). At its heart, the committee’s statement of task assumes that there is an unmet need that exists for individuals, families, and communities to improve eye and vision health across the lifespan of individuals. By default, the task also assumes a need to establish the conditions that will allow community participants and leaders to evaluate and weigh vision impairment in their communities against other health priorities and also consider how programs that focus on vision impairment could enhance programs aimed at other health issues.

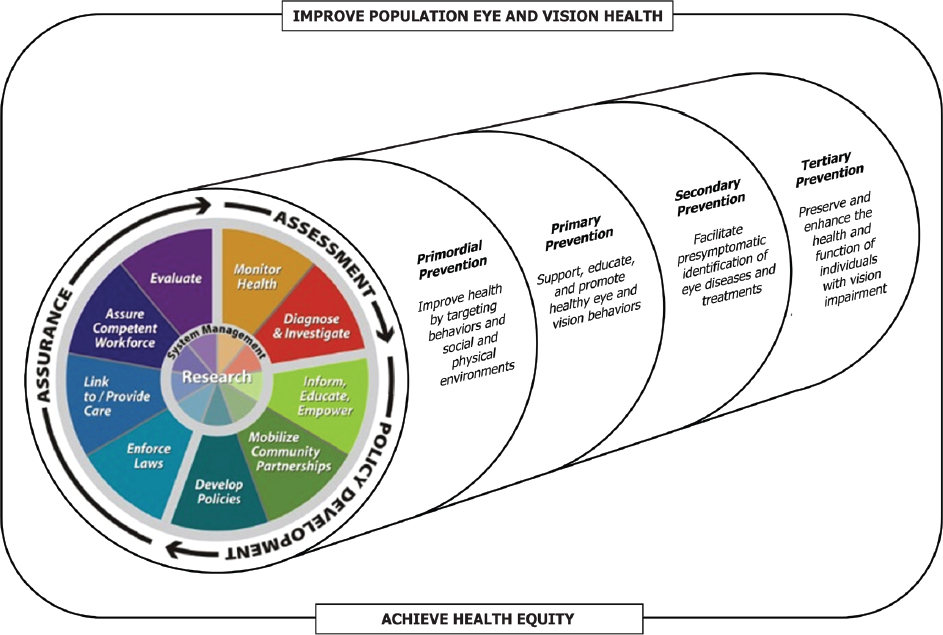

To guide its deliberations, the committee developed a conceptual framework for action to achieve the ultimate outcome—improved population eye and vision health and health equity (see Figure 9-1). The committee’s recommendations are organized by the five core action areas: (1) facilitating public awareness through timely access to accurate and locally relevant information; (2) generating evidence to guide policy decisions and evidence-based actions; (3) expanding access to clinical care; (4) enhancing public health capacities to support vision-related activities; and (5) promoting community actions that encourage eye and vision healthy environments. These action areas, which are described below, provide the framework by which the committee introduces its recommendations. The eight guiding principles defined in Chapter 1 should guide all actions within the framework for action—that is, they should be population-centered, collaborative, culturally competent, community-tailored, evidence-based, integrated, standardized, and adequately resourced.

Many of the following nine recommendations are broadly framed but are critical to establishing conditions that will support a sustainable population health initiative that achieves a long-term reduction in vision impairment and its consequences. These recommendations provide the foundational support for other, more specific actions by stakeholder groups, as described in the concluding section of this chapter and throughout this report. The result could establish new policies and practices that will have an impact on other dimensions of health and quality of life (QOL) in the United States.

FACILITATE PUBLIC AWARENESS THROUGH TIMELY ACCESS TO ACCURATE AND LOCALLY RELEVANT INFORMATION

Establish Eye and Vision Health as a National Priority

The process of vision loss can affect anyone at any time and may occur suddenly and completely—for example, from injury—or may progress over time, with permanent structural damage leading to progressive changes in eye function until more pronounced deficits become noticeable. The resulting vision impairment—the functional limitation of the eye or visual system that results from vision loss—remains an unmet and urgent public health threat in the United States (HHS, 2015; NEI/NIH, 2004; USPSTF, 2009). In the United States, more than 4.24 million adults ages 40 and older suffer from uncorrectable vision impairment and blindness (Varma et al., 2016), and more than 2.155 million children and young adults have uncorrectable vision impairment (Wittenborn et al., 2013). Millions more experience vision impairment from uncorrected refractive error and cataracts (CDC, 2015c; Varma et al., 2016; Wittenborn and Rein, 2016). In 2011, the total estimated direct and indirect costs of vision impairment and eye disease were $138 billion (Wittenborn and Rein, 2013). These costs will only increase as the United States’ population ages, and these costs are projected to consume an ever greater proportion of the gross domestic product (Varma et al., 2016).

According to a recent online poll, 88 percent of the 2,044 respondents surveyed identified good vision as vital to maintaining overall health, and 47 percent rated losing their vision compared to loss of limb, memory, hearing, or speech as “potentially having the greatest effect on their day-to-day life” (Scott et al., 2016, p. E3). Despite the public’s perception of the importance of good vision, millions of people continue to grapple with undiagnosed or untreated vision impairment (CDC, 2015d; Varma et al., 2016; Wittenborn and Rein, 2016). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) supports a number of federal programs and institutes, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Vision Health Initiative (VHI) and the National Eye Institute’s (NEI’s) National Eye Health and Education Program (NEHEP), that focus on vision loss and fund various activities to combat the effects of poor eye and vision health on at-risk populations (CDC, 2015a). Yet, eye and vision health remain relatively absent from national health priority lists, including efforts to stem the impact of chronic diseases.

A number of factors contribute to the absence of focused and sustained programmatic investment that translates into widespread action. Historically, eye care was considered separate from the more general field of medicine, and various tensions between different eye care professionals continue to contribute to the fragmentation of eye care, which excludes eye health from conversations about broader strategies to improve and measure the overall health of populations. The lack of coordination within or across

federal agencies further dissipates the presence of eye and vision health as a public health issue on the national stage. Greater national and directed attention is needed to raise awareness among public health practitioners, health professionals, policy makers, and the public about the importance of eye and vision health as an indicator of health equity and overall health and as a key factor affecting QOL.

A Call to Action “is a science-based document to stimulate action nationwide to solve a major public health problem” (U.S. Surgeon General, n.d.). HHS, most often through the Office of the Surgeon General, uses calls to action to draw attention to important public health issues, including promotion of walking and walkable communities, the prevention of skin cancer and suicide, improving the health and wellness of persons with disabilities, promoting oral health, and the reduction of underage drinking (U.S. Surgeon General, n.d.). These documents, along with other reports, are often used to establish a baseline from which to measure improvement in particular areas (e.g., Anstev et al., 2011; Mertz and Mouradian, 2009; U.S. Surgeon General, 2014).

Vision loss and impairment qualify as a public health problem, based on the CDC’s definition, in that they: (1) affect a large number of people; (2) impose large morbidity, QOL, and cost burdens; (3) the severity of the problem is increasing and is predicted to continue increasing; (4) the public perceives the problem to be a threat; and (5) community or public health-level interventions are feasible (CDC, 2009). Similarly, the NEI, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), and the World Health Organization have identified vision impairment in various populations as national or global public health problems (HHS, 2015; NEI/NIH, 2004; WHO, 2015). Moreover, most causes of vision impairment are chronic, continuously present, and require ongoing management over the lifespan of an individual to maintain the activities of daily living. A greater federal presence, is needed to elevate eye and vision health as a population health focus among the general public and different sectors of society.

Recommendation 1

The Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should issue a Call to Action to motivate nationwide action toward achieving a reduction in the burden of vision impairment across the lifespan of people in the United States. Specifically, this Call to Action should establish goals to:

- Eliminate correctable and avoidable vision impairment by 2030,

- Delay the onset and progression of unavoidable chronic eye diseases and conditions,

- Minimize the impact of chronic vision impairment, and

- Achieve eye and vision health equity by improving care in underserved populations.

A Call to Action is needed to harness the collective voice of the nation’s population health system (including the governmental public health systems, clinical care systems, employers and businesses, media, nonprofit organizations, education sectors, other government agencies, and communities) to initiate nationwide actions that emphasize eye and vision health promotion. In pursing the Call to Action, the Secretary should leverage the expertise of the Surgeon General of the United States. These Calls to Action usually include a description of the public health problem, a vision statement, general goals, and key actions to support these goals. They also usually summarize the scientific evidence currently available to support behavior change, and they may include additional resources, such as checklists and guides for different stakeholders (U.S. Surgeon General, n.d.). At a minimum, the highlighted actions in a Call to Action should reflect the goals articulated by the committee and should focus on changing perceptions; overcoming barriers; building a science base around primordial, primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention; increasing clinical and public health diversity, capacity, and flexibility; and increasing collaboration.

The specificity provided in the committee’s recommendation is meant to fuel conversations about what should be technically possible and what is feasible at what stage. For example, by definition, correctable and avoidable vision impairment should be something that can be eliminated. There are, of course, limitations in resources that may affect the ability to reach this goal. Similar considerations exist for slowing the progression of vision loss or improving the function of people with vision impairment through access to high-quality treatments or services. However, in setting this high bar against which to measure success, the committee hopes to stimulate innovative thinking about how to use the available resources more wisely and to encourage debate about the role that eye and vision health should play in broader initiatives to support healthy environments and reduce health inequities in the United States. This Call to Action sets the stage for the remaining recommendations.

Promoting Greater Public Awareness

Enhancing public knowledge about a health threat is a fundamental first step in informing discussions that promote behavior change across multiple determinants of health and aligning health policies with general public health interests. Unfortunately, lack of awareness of vision and eye health issues remains “a major public health concern,” especially in the context of linking patients into care and attempting to make population-level

changes in behavior and health practice (Bailey et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2012). Individuals are often unaware of what the most common threats to vision are, how the physiological progression of many eye diseases occurs, early signs of vision loss, and what steps can be taken to reduce the risk of vision-threatening eye disease, conditions, and events and the impact of subsequent vision loss (Alexander et al., 2008; Chou et al., 2014; Lam and Leat, 2015; NEI/LCIF, 2008; Varano et al., 2015). Combined with the asymptomatic nature of many eye diseases and conditions, this lack of awareness can have significant ramifications on overall health.

Although rarely adequate by themselves, public awareness campaigns can be an effective tool for improving knowledge about key messages related to health within populations (Bray et al., 2015; Oto et al., 2011) and are one essential part of an effective population health strategy. Zambelli-Weiner and colleagues (2012) state that public health strategies, which include efforts “to enhance awareness, to promote education, and to increase access to successful prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation services among populations at risk for poor vision outcomes can improve vision health in the United States and globally” (pp. S23–S24). Many current education initiatives and programs focus on particular etiologies of vision impairment among the most at-risk populations. For example, the NEHEP includes vision education programs focusing on people living in Hispanic/Latino communities; people at risk for glaucoma, diabetic eye disease, and age-related conditions; and people living with low vision (NEI/NIH, 2015). Although these topics and populations are important, elevating the status of eye and vision health at a national level will require much broader messaging that emphasizes eye and vision health across the lifespan.

Achieving the goals outlined in Recommendation 1 will require having reliable, consistent, evidence-based information that is available and accessible by a variety of stakeholders to increase overall knowledge and to support policies, practices, and behaviors that promote good eye and vision health, encourage appropriate care to correct or slow progression of a vision-threatening disease or condition, or improve function when vision impairment is uncorrectable. This approach must target various audiences and consider a wide range of factors affecting eye and vision health in communities, including individual-directed strategies, mass media campaigns, and environmental and policy changes across multiple settings within defined geographic areas (e.g., city, state, province, or country).

Recommendation 2

The Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in collaboration with other federal agencies and departments, nonprofit and for-profit organizations, professional organizations, employers, state and

local public health agencies, and the media, should launch a coordinated public awareness campaign to promote policies and practices that encourage eye and vision health across the lifespan, reduce vision impairment, and promote health equity. This campaign should target various stakeholders including the general population, care providers and caretakers, public health practitioners, policy makers, employers, and community and patient liaisons and representatives.

A coordinated public awareness campaign should focus on topics such as the various risk and protective factors across the lifespan for the major causes of vision loss, the link between eye and vision health and other measures of health (such as chronic conditions, subsequent injury, and psychological issues), vision loss as a chronic condition, when and how to access eye care and rehabilitative and support services (see Recommendation 5), and the impact of the social and built environments on one’s ability to maintain optimal health and visual function following significant vision loss. For example, messages could target private businesses to convince them to cultivate healthy workplace design and practices that take into account screen time, lighting conditions, or other interventions and accommodations that can improve or preserve eye health and visual functioning. Moreover, the public awareness campaign should also target eye care professionals and public health practitioners, emphasizing the connection between eye and vision health and public health practice and how to translate clinical language into evidence-based policies, including those that eliminate the artificial divide that exists between eye and vision health and general medical care. These messages could be combined with similar messages about other sensory health issues, such as hearing loss.

To meet the goals outlined in recommendation 1, a successful public awareness campaign must emphasize a variety of activities, coordinated and supported by various groups, to enhance public awareness around specific needs for knowledge about eye and vision health across the lifespan. For example:

- The CDC and the NEI, in consultation with professional organizations, state and local public health departments, and patient advocacy groups, should enhance the development and impact of vision health education materials that appear in multiple formats and are tailored to diverse audiences.

- National and state departments of labor, national and local labor unions, and nonprofit organizations working in the sphere of labor and worker rights should incorporate educational programs on eye safety and vision-related employee rights into larger advocacy and worker education agendas.

- Governmental public health departments and population health research centers, in collaboration with the American Public Health Association and the Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health, should jointly fund and develop post-professional training on eye and vision health for public health practitioners and researchers involved in public health surveillance activities; such training is needed to augment the capacity of public health actors and surveillance systems to address eye and vision health issues.

- HHS and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, in collaboration with experts in the field of vision rehabilitation, should develop educational materials and provide technical assistance for private and public employers to prioritize the vision health of employees, support work practices and environments that are conducive to preservation of visual functioning, and ensure that workplace accommodations for visually impaired employees meet Americans with Disabilities Act standards.

- Nonprofit organizations dedicated to eye health and disease should partner with HHS and other agencies to support a public awareness campaign and use the campaign to springboard additional efforts in at-risk and disease-specific communities.

- Nonprofit organizations providing resources for at-risk individuals (who are at risk due to socioeconomic reasons, cognitive, physical or mental health issues, or geographic reasons) should participate in the dissemination of material about the importance of eye and vision health from the public awareness campaign in an effort to target populations that are often not reached by the efforts of most campaigns.

GENERATE EVIDENCE TO GUIDE POLICY DECISIONS AND EVIDENCE-BASED ACTIONS

Enhancing Vision Surveillance

Surveillance is “the ongoing systematic collection, analysis and interpretation of health-related data essential to the planning, implementation, and evaluation of public health practice, closely integrated with the timely dissemination of these data to those who need to know” (Thacker and Berkelman, 1988, p. 164). By this definition, no system for the surveillance of eye disease or vision impairment and blindness exists.

Vision impairment and blindness are appropriate targets for surveillance because they adversely affect a large portion of the population, affect populations unequally, can be improved by treatment and preventive efforts, and will become an increasing burden as the population ages (NEI/NIH, 2004; Saaddine et al., 2003). A comprehensive, nationally representative surveillance system for eye and vision health is needed to make it possible to better understand the epidemiological patterns, risk factors, comorbidities, and costs associated with vision loss. Such data will allow health care professionals and public health decision makers to better characterize the nature and extent of the public health burden; risk factors and at-risk populations; disparities in access, care, and outcomes; and successful interventions (West and Lee, 2012).

The absence of a comprehensive, sustainably implemented and funded surveillance system with validated measures, verifiable data, and interoperable databases creates challenges for population vision health. Key among these is the inability to determine the prevalence and costs of eye disease and vision impairment; to identify at-risk groups, barriers to care access, and health disparities; and to assess the effectiveness of treatments and therapies and the availability and adequacy of vision care system resources at the national, state, and local levels.

Recommendation 3

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) should develop a coordinated surveillance system for eye and vision health in the United States. To advise and assist with the design of the system, the CDC should convene a task force comprising government, nonprofit and for-profit organizations, professional organizations, academic researchers, and the health care and public health sectors. The design of this system should include, but not be limited to:

- Developing and standardizing definitions for population-based studies, particularly definitions of clinical vision loss and functional vision impairment;

- Identifying and validating surveillance and quality-of-care measures to characterize vision-related outcomes, resources, and capacities within different communities and populations;

- Integrating eye-health outcomes, objective clinical measures, and risk/protective factors into existing clinical-health and population-health data collection forms and systems (e.g., chronic disease questionnaires, community health assessments, electronic health records, national and state health surveys, Medicare’s health risk assessment, and databases); and

- Analyzing, interpreting, and disseminating information to the public in a timely and transparent manner.

Implementing a coherent surveillance system of eye and vision health will require a long-term commitment from the CDC and its partners. Most existing national vision surveillance activities consist of modules that supplement pre-existing surveys. These surveys are not ideal (e.g., they are reliant on self-report items rather than objective clinical data, and they fail to capture key populations of interest), but they are a good place from which to begin enhanced surveillance efforts. Currently, material specific to eye and vision health is under consideration for inclusion in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. The committee encourages inclusion of an eye-specific component within the next versions of these surveys.

In the long term, a more comprehensive approach to eye and vision health surveillance is needed to allow for a better and more accurate characterization of the population burden of eye disease and conditions and resulting vision impairment in the United States, with special emphasis on the need to identify the most at-risk and burdened populations. Surveillance efforts should be real-time and include a focus on at-risk communities and populations and should identify the root causes of disparities in vision health and care and the trends in vision health and care over time. Using a “big data” approach, the CDC should also gather eye and vision data in the various disease-specific registries managed by nonprofits, clinicians, companies, and government entities.

The CDC has already taken steps toward this goal by funding a grant that will “develop, test, and implement a vision and eye health surveillance system, using existing surveys, as well as administrative and electronic data sources” (CDC, 2015b). The grant was awarded in summer 2015, and the research it is funding is currently in the planning stages. The committee applauds these efforts and urges government contractors to inform the deliberations and consider the conclusions of the recommended task force. The task force should focus on the development of standardized definitions for all relevant terms used in surveillance, including “vision

impairment,” “visual functioning,” and “vision-related quality of life,” among others. Information technology should also focus on the development of standardized, validated, and verifiable measures; a strategy for transitioning from subjective and self-reported measures to objective measures; and the identification of existing data collection efforts, such as the community health risk assessments developed by nonprofit and public hospitals and health risk assessments performed by providers, that could incorporate standardized eye health metrics into existing forms and databases. The use of standardized vision health modules as supplements to existing surveys and surveillance efforts should also be promoted. Opportunities to develop and implement an eye disease registry capitalizing on the growing power and availability of electronic health records should be explored along with the specification of metrics for quality of care improvement.

Expanding Knowledge Related to Eye and Vision Health

Understanding the factors that affect the risk of vision impairment for different populations, the barriers to accessing care, interventions to prevent visual impairment and maintain eye function, and ways to improve the quality of care is fundamental to designing and identifying opportunities that minimize vision loss now and that will result in new knowledge and strategies to further reduce the long-term impact of vision impairment. HHS supports a number of federal programs and institutes that focus on vision loss and fund various activities to combat the effects of poor eye and vision health on at-risk populations (CDC, 2015a). The CDC and the NEI, as well as many other federal agencies, departments, and institutes have supported programs and initiatives to improve eye and vision health in different capacities and populations (ACL, n.d.; CDC, 2009; CMS, 2015; DoD, 2016; DOL, n.d.; >ED, n.d.; HHS, 2015; HUD, 2016; Indian Health Service, 2008; NEI/NIH, 2015; Office of Head Start, 2015; USDA, 2015; VA, n.d.). Nonprofit organizations, professional groups, and private entities have bolstered these efforts through their own research and activities, including important and considerable collaborations with federal and state governments.

Despite these activities, eye and vision health are insufficiently represented as a programmatic focus in federal government programs overall, and existing research programs lack coordination within and across federal agencies and institutes. Moreover, significant research and knowledge gaps persist concerning eye and vision health, as documented throughout this report. This is particularly true about nonclinical research areas, i.e., more traditional public health focused research on primordial and primary prevention. Establishing a unified research agenda with larger financial and programmatic support to develop and advance knowledge about eye and

vision health can maximize efficiencies and build on the strengths of established programs across a broad portfolio of topics and programs, which must include more than basic and clinical research.

The fundamental need to understand how upstream determinants of health affect the development of vision loss and impairment and how best to diagnose and treat eye diseases and conditions within different populations requires a more comprehensive approach to eye and vision health research, which in turn should strengthen both the public health and clinical response to vision loss in the long term. Moreover, knowledge about the prevalence of, incidence of, causes of, and risk and protective factors for vision impairment is severely lacking, as is an understanding of the impact of specific interventions to improve outcomes from vision impairment. Many entities have made notable efforts to enhance research to inform eye and vision health practice and outcomes, including the CDC’s VHI, the NEI, Research to Prevent Blindness, Prevent Blindness, and many other national and state-level programs (see Chapter 3). However, these efforts lack coordination and a single research agenda that explains how these efforts as a whole can be used to enhance understanding and inform decisions related to eye and vision health at the federal, state, and local levels (CDC, 2009; NEI/NIH, 2015; Prevent Blindness, 2016; Research to Prevent Blindness, 2016).

Recommendation 4

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should create an interagency workgroup, including a wide range of public, private, and community stakeholders, to develop a common research agenda and coordinated eye and vision health research and demonstration grant programs that target the leading causes, consequences, and unmet needs of vision impairment. This research agenda should include, but not be limited to:

- Population-based epidemiologic and clinical research on the major causes and risks and protective factors for vision impairment, with a special emphasis on longitudinal studies of the major causes of vision impairment;

- Health services research, focused on patient-centered care processes, comparative-effectiveness and economic evaluation of clinical interventions, and innovative models of care delivery to improve access to appropriate diagnostics, follow-up treatment, and rehabilitation services, particularly among high-risk populations;

- Population health services research to reduce eye and vision health disparities, focusing on effective interventions that promote eye healthy environments and conditions, especially for underserved populations; and

- Research and development on emerging preventive, diagnostic, therapeutic, and treatment strategies and technologies, including efforts to improve the design and sensitivity of different screening protocols.

A research agenda that supports population health efforts to promote eye and vision health necessarily will include a broad portfolio of topics and programs, which must include more than basic and clinical research. An understanding of (1) the factors that affect the risk of vision impairment for different populations, (2) the barriers to accessing care, (3) effective interventions to prevent visual impairment and maintain eye function, and (4) ways to improve the quality of care is fundamental to designing and identifying opportunities that will minimize vision loss now and produce new knowledge and strategies to further reduce the long-term impact of vision impairment.

A common research agenda would allow for maximum efficiencies and reduce duplicative efforts and investments in research across diverse disciplines and focus areas. This will be essential at the beginning of a national effort to reprioritize eye and vision health because sustained and larger financial and programmatic support for such research is more likely to occur in the long term with better evidence. Although the committee believes that both sufficient evidence, as documented throughout this report, and also common sense support the conclusion that eye and vision health is an essential underpinning of the overall health of communities, more robust and recent research can help clarify the most important risk and protective factors associated with specific eye diseases, conditions, and injuries in order to guide decision making and programmatic emphasis at various levels and in different settings to enhance the value of future investments in eye and vision health. Demonstration projects are needed to test the most cost-effective ways to meet the eye care needs of underserved areas (e.g., testing incentives for provider practice, specialized training for providers already in the area, and the use of novel screening technologies). Vision rehabilitation is another area where significant evidence gaps were identified (see Chapter 8); filling in these gaps is a high priority in order to guide policies and community efforts intended to reduce the societal cost of chronic vision impairment.

Population health services research should focus on barriers to performance on the part of local and state health departments and should explore methods used in jurisdictions where public health agency efforts have been successful (and have failed) in advancing eye and vision health. Health services research should include programs and support to promote the interpretation and dissemination of research findings to various audiences. This could include tests of models of dissemination of information and best practices, including administrative best practices and funding procedures,

to determine which are the speediest at improving the adoption of new methods, processes, and outcomes. To this end, the interagency workforce should include expertise on translational research and implementation science in order to improve the vision care system’s response to the findings of new health services and public health services and epidemiological research and to speed the adoption of novel treatments, therapies, and technologies and models of care and reimbursement.

The committee suggests that research on examination and screening should prioritize the development of evidence to support guideline formation (see Recommendation 5) for high-risk groups, including children in age groups with a high prevalence of risk factors for amblyopia and strabismus and individuals diagnosed with diabetes. Similarly, research on best-practice guidelines should prioritize referral patterns of primary care and primary eye care provider groups, because these groups see the greatest number of patients and represent the first step in the continuum of care.

The committee acknowledges that the research agenda as outlined is very broad and that priorities under each bullet should be set based on available resources and greatest need in terms of research gaps. However, it is important that each bullet be addressed as part of a comprehensive approach to eye and vision health. Consideration should be given to innovative research methodologies and strategies to improve efficiency.

EXPAND ACCESS TO APPROPRIATE CLINICAL CARE

Establishing Unified, Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines

Professional guidelines are an important tool to advance policies and practices that promote high-quality care for everyone. As discussed in Chapter 7, guidelines are often used to educate the public as well as public health and health care professionals about the foundational elements of value-driven payment policies, and they are used as baselines from which to measure quality improvement and enhanced accountability for care processes and patient health outcomes. Unfortunately, no single set of clinical practice guidelines or measures in eye and vision care exists, and there are marked

discrepancies in the current screening and eye examination guidelines for asymptomatic people. This often reflects the absence of robust research and political tensions within the field of eye and vision health. Available guidelines provide inconsistent recommendations concerning essential measures. For example, the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Optometric Association disagree on the appropriate frequency of eye examinations, with the former recommending less frequent eye examinations (e.g., AAO, 2015; AOA, 2015). In the case of vision screening, evidence-based recommendations from USPSTF, which focuses on primary care practice, calls for vision screening of children ages 3 to 5 only (USPSTF, 2009), whereas consensus-based recommendations from the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (AAPOS), and the National Expert Panel recommend screening for additional age groups (AAO, 2014; AAPOS, 2014; Cotter et al., 2015; Hartmann et al., 2015). The American Academy of Ophthalmology and AAPOS, but not USPSTF, recommend specific screening tests (AAO, 2012; AAPOS, 2014). Uncertainty as to the appropriate frequencies of testing may lead to either unnecessary or inadequate care, while discrepancies and contradictions among recommendations contribute to patient and provider confusion concerning the standards of care.

Recommendation 5

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should convene one or more panels—comprising members of professional organizations, researchers, public health practitioners, patients, and other stakeholders—to develop a single set of evidence-based clinical and rehabilitation practice guidelines and measures that can be used by eye care professionals, other care providers, and public health professionals to prevent, screen for, detect, monitor, diagnose, and treat eye and vision problems. These guidelines and supporting evidence should be used to drive payment policies, including coverage determinations for corrective lenses and visual assistive devices following a diagnosed medical condition (e.g., refractive error).

Evidence-based guidelines provide guidance based on objective evidence for a variety of care providers to improve the uniformity and quality of the care they deliver to patients. For example, the recommended guidelines should be used to guide decisions related to payment policies, and health insurance coverage determinations for comprehensive eye examinations,1 preventive services and treatments (including corrective

___________________

1 The committee defines a comprehensive eye examination as a dilated eye examination that may include a range of other tests, in addition to the dilation of the pupil to see the retinal structures (or back of the eye).

lenses), and rehabilitation (including assistive devices). Particular attention needs to be paid to assuring that essential services and treatments are affordable, particularly for the most vulnerable populations. Recommended guidelines would also establish a uniform baseline from which to measure improvement in care processes and patient health outcomes. This should include an evaluation of health care provider adherence to guidelines. Finally, the guidelines promote accountability by a multitude of factors by enabling performance comparisons and the appropriate use of evidence-based technology by including health care system, provider, geographic area, and population characteristics.

Guidelines should include, but not be limited to (1) the schedule and components of comprehensive eye examinations; (2) the appropriateness of particular diagnostic, treatment, and management strategies for specific eye diseases and conditions; and (3) criteria to facilitate appropriate followup care, both within and external to eye and vision care, and to ensure a continuum of health care that is focused on the specific eye health needs and the overall health of populations. These guidelines should apply to both the general practice of medicine and to eye care specifically, with an emphasis on steps to increase the integration of services to promote both eye and vision health and overall health. Updates to the guidelines should occur periodically, and the process should include a mechanism by which critical data findings can be incorporated into or recognized in addendums to guidelines prior to the formal guideline updates.

It is important that the development of evidence-based guidelines adhere to particular standards, to the extent possible, so as to ensure robust and comprehensive support for recommended actions. These standards can include the Institute of Medicine standards for trustworthy guidelines (IOM, 2011a) or other assessment tools (see Brouwers et al., 2010, for a description and comparison of some available tools). Assessment can include stakeholder involvement (including patient representatives), rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, editorial independence, disclosed external review methods, economic considerations, the roles of the guideline development group members, disclosed search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria for the evidence review, or the outcomes of public input.

There will be challenges in implementing this recommendation. Part of the problem in advancing eye health, as pointed out in report text, is that the professional groups involved in eye and vision care have differences in guidelines. This recommendation represents a necessary and essential first step to align the interests of the eye and vision field through an exercise that will not only improve clarity for the public, but also provide an evidence-based platform from which to advocate for necessary and overdue payment

policies and research that can reduce disparities in eye and vision health for the most vulnerable members of society.

Enhancing Eye and Vision Health in Professional Training and Education

Historical divisions within the vision care system, combined with the specialization of eye care to the extent that it essentially operates as a “siloed” service rather than an incorporated component of primary health care, has led to a lack of vision health–related content in traditional health care professional training, public health education, and quality monitoring. Similarly, cross-disciplinary training in public health is generally underrepresented in formal education and certification programs for providers working in optometry, ophthalmology, and vision rehabilitation. Limited knowledge of the roles and competencies of other vision health professions and tensions surrounding the scope of practice undermine efforts to integrate vision care with other health care services, diminish the timeliness and quality of care by hindering appropriate referral practices, and generally inhibit an interprofessional culture of collaboration and coordination among ophthalmologists, optometrists, primary care physicians, and providers working in vision rehabilitation. Thus, fragmentation is both a cause and consequence of the lapses in the health care and public health education system.

To cultivate professional relationships and collaboration that will advance eye and vision health across medicine and beyond clinical care, it will be important to establish common expertise that can align overarching objectives and action among health professionals. The CDC has noted the need to elevate ophthalmic education in medical curriculums (CDC, 2009; Shah et al., 2014). With a greater focus on population health in clinical care (Berwick et al., 2008), new skills will be needed to ensure that health care professionals understand the types of patient experiences and data that are relevant to population health activities, including the moral imperative to reduce inequities in both health and health care. Moreover, population health practitioners should be familiar with eye and vision health, its risk factors, and the relationship between vision loss and other chronic health conditions. Translating this knowledge into meaningful patient interactions will require cultivating trust among different patient populations, providers, and public health practitioners.

Cultural competency helps build concordance between patients and health care providers by challenging providers to think outside of their strict biomedical constructs and respond to the cultural barriers that inevitably arise because of patients’ diverse belief systems and views about health, health care, and health care providers. The continuing development, implementation, and evaluation of cultural competence programs, training

modules, and educational tools designed to improve the affective dimensions of communication and clinical behavior, combined with an increasing diversity in the health care workforce, can help increase patient–provider concordance and reduce implicit bias, which will not only help with the public health challenge of eliminating ethnic and cultural disparities but also address various contributors to health outcomes that affect the health of vulnerable populations (Elam and Lee, 2013; IOM, 2003b; Sabin and Greenwald, 2012).

Recommendation 6

To enable the health care and public health workforce to meet the eye care needs of a changing population and to coordinate responses to vision-related health threats, professional education programs should proactively recruit and educate a diverse workforce and incorporate prevention and detection of visual impairments, population health, and team care coordination as part of core competencies in applicable medical and professional education and training curricula. Individual curricula should emphasize proficiency in culturally competent care for all populations.

In essence, this recommendation is about creating a common language that can help advance communication and strategic planning among groups that have not traditionally worked together in the same capacity as with other public health priority areas. There are three targets of this recommendation. First, eye care professionals need to be knowledgeable about the basics of public health and how eye and vision health relate to other measures of well-being and health. Ophthalmology residencies should include practical experiences in interdisciplinary settings, including community health centers. Optometry programs should include education in public health fundamentals and practical experiences working in primary care settings.

Second, other health care providers need to understand the importance of eye and vision health in maintaining the overall health of their patient populations and the role that eye care can play in identifying non-eye-related diseases and conditions. The training of primary care physicians should include developing competency at identifying vision impairment and the need for eye care as well as teaching them to be familiar with the underlying determinants of health, especially those that are risk factors for vision loss among vulnerable and at-risk populations.

Third, public health practitioners need to understand the basics of eye health and how it relates to programs that are eye and vision health specific; or how eye and vision health metrics can either complement or improve existing programs for related chronic diseases or health conditions. All public health programs should include modules on the vision care system and on the roles of other providers in that system. Training should emphasize

the role of public health experts as coordinators and conveners of stakeholders in systems lacking integration. Research is needed to determine how best to utilize the eye and vision care, primary care, and public health workforces. Incentives and technologies to optimize workforce capacity should be identified and employed. In all of these efforts, patients and advocates should be involved to offer real-world patient-reported experiences and outcomes.

In addition to having basic knowledge about eye health and related risk and protective factors, health professional school students should be knowledgeable about population health approaches and about the roles and competencies of public health experts and vision rehabilitation therapists and other types of therapists in vision care. Training for vision rehabilitation and other vision therapists should include practical experiences working as part of an interdisciplinary rehabilitation team as well as instruction in the competencies and roles of physical and occupational therapists, orientation and mobility specialists, and optometrists and ophthalmologists.

As one potential enforcement mechanism, federal funding for training programs could be contingent upon these steps being taken and on the adoption and presentation of the curricula based on federal consensus guidelines.

ENHANCE PUBLIC HEALTH CAPACITIES TO SUPPORT VISION-RELATED ACTIVITIES

Integrating Eye and Vision Care

Population health approaches focus on the broad determinants of health, which include the social and environmental determinants of health across a lifespan, which in turn include (1) innate individual traits (e.g., age, sex, race, genetics); (2) individual behaviors; (3) social, family, and community networks; (4) living and working conditions (e.g., psychosocial factors, employment status and occupational factors, socioeconomic status, and health care services); and (5) broad social, economic, cultural, health,

and environmental conditions and policies at the global, national, state, and local levels (e.g., economic inequality, urbanization, mobility, and cultural values) (IOM, 2003a). Responsibility for improving population health has never been the sole province of governmental public health departments. Governmental public health departments must work with and through other stakeholders, including other government agencies, the clinical care system, employers and businesses, media, nonprofit organizations, the education sector, and the community to reach established goals (IOM, 2003a, 2011b). Successful health promotion in eye and vision health will require innovative partnerships that engage in a variety of activities that advance different objectives within population health.

Integrating public health and local health care systems is an important strategy to improve community health (CDC, 2007). A well-functioning medical care system can expand access to appropriate eye and vision care services, allowing public health agencies to focus on preventive policies and action and assurance. Such preventive actions include linking people to needed care, assessing care quality, and promoting community support and policy and environmental conditions that maximize health (IOM, 2003a). Public health agencies and departments can also extend the reach of health care services through vision-specific programs. Unfortunately, there has been insufficient partnering to coordinate existing and emerging programs, policies, and quality improvement activities that either directly or indirectly affect eye and vision health.

Recommendation 7

State and local public health departments should partner with health care systems to align public health and clinical practice objectives, programs, and strategies about eye and vision health to:

- Enhance community health needs assessments, surveys, health impact assessments, and quality improvement metrics;

- Identify and eliminate barriers within health care and public health systems to eye care, especially comprehensive eye exams, appropriate screenings, and follow-up services, and items and services intended to improve the functioning of individuals with vision impairment;

- Include public health and clinical expertise related to eye and vision health on oversight committees, advisory boards, expert panels, and staff, as appropriate;

- Encourage physicians and health professionals to ask and engage in discussions about eye and vision health as part of patients’ regular office visits; and

- Incorporate eye health and chronic vision impairment into existing quality improvement, injury and infection control, and behavioral change programs related to comorbid chronic conditions, community health, and the elimination of health disparities.

Opportunities to realize and support the integration of health care and public health systems can take many forms. Health care organizations and providers can benefit from public health expertise related to existing population health databases covering eye and vision health, assessment tools, existing community relationships, and existing knowledge and resources in order to incorporate eye and vision health into existing programs or extend vision services to populations in need of targeted preventative, clinical, or rehabilitative care. Public health departments can convene the partners and support the integration of the various capabilities around a shared vision and shared goals. Public health departments can also use the clinical expertise of health care workers to design better measures for vision surveillance, to conduct screenings, and to raise patient awareness of eye disease through counseling and health education. Federal guidelines may be a useful tactic for promoting harmonization among states and promoting a shared governance model to encourage long-term sustainability. Specific opportunities for effective collaboration include

- Local public health departments should identify populations at increased risk of developing eye disease and design vision screening initiatives targeting them for intervention. Ophthalmologists, optometrists, school nurses, and other health care professionals should ensure the quality of these efforts by performing screenings, referring patients for follow-up care, and educating patients on eye disease.

- Local public health departments should work to strengthen relations among primary care providers, eye care providers, health care professionals working in vision rehabilitation, social services, and other community health workers in order to improve the continuity, timeliness, and adequacy of eye care.

- Public health departments should lead the development and dissemination of health education materials that educate patients on making changes to lifestyle risk factors for eye disease, on health impacts, on the need for eye exams, and on treatments, and they should clarify best practices for clinicians.

- Ophthalmologists, optometrists, and primary care physicians should collaborate with biostatisticians and epidemiologists in public health departments on the identification of key indicators of eye and vision health and on the development of surveys and other surveillance tools that accurately measure these indicators.

- Health informaticians should aid health care organizations and public health departments in efforts to develop shared data systems that allow clinicians to tailor patient education and outreach to identified vision health risks and that allow epidemiologists to monitor changes in disease prevalence and adapt public health programs and policies to community needs.

Effective partnerships to advance eye and vision health will require a strong, effective governmental member at each locus of government (local, state, or federal). This is resource intensive and requires a long-term commitment of senior leadership and interest among nongovernmental partners to develop, implement, and evaluate the gains and efficiencies over time for different populations.

Enhancing State and Local Capacities

State health departments can make substantial contributions to national vision health efforts. First, their involvement in the planning process helps to develop realistic action plans and ensure that the appropriate high risk populations are targeted. State health departments provide an important link between federal and community programs, which can incorporate vision health strategies where appropriate. Second, state and local health departments are the logical, local conveners for collaborations between a variety of community stakeholders and surveillance efforts related to eye and vision health.

Advancing eye and vision health as a programmatic focus will require more than simply asking governmental public health agencies and departments to place greater emphasis on the topic. Governmental public health professionals are responsible for a wide range of activities and programs that face dwindling resources in the face of increasing demand. Unfortunately, current state and local public health agencies and departments struggle to meet state mandates and requirements in the face of declining public investment, limited political power, and competition (Jacobson et al., 2015). The result is that other, more traditional public health activities, such as surveillance, health promotion, and policy development (including tracking underlying social and environmental conditions as well as eye and vision health) do not receive adequate attention or resources (Brooks et al., 2009; Honoré and Schlechte, 2007; Jacobson et al., 2015).

Federal agencies charged with various responsibilities to promote public health are uniquely situated to provide the needed resources and expertise that will allow state and local health departments to incorporate eye and vision health as a programmatic focus. For example, in 2016, the CDC implemented a vision grant program, in partnership with state-based

chronic disease programs and other clinical and nonclinical stakeholders “to engage in strategic initiatives or activities designed to improve vision and eye health” (NACDD, 2016). The current grant program will award three states an average of $25,000 toward the development of activities that (1) “achieve the overall goal of advancing vision loss and eye health as public health priorities”; (2) “implement a vision and eye health intervention that focuses” on characterizing the burden of eye disease or vision loss, promotes systems change, or implements interventions related to eye and vision health; and (3) focus on sustainability beyond the initial funding period (NACDD, 2016).

Unfortunately, public health strategies to promote eye and vision health are rarely supported as a categorical focus or even as part of chronic disease programs in most state and local health departments because of limitations in resources and shifting priorities. The programmatic emphasis in governmental public health departments typically complements national public health priority lists, which do not typically include eye and vision health or chronic vision impairment (e.g., CDC, 2015d). Moreover, the degree of flexibility in how state and local governments use federal grant funds varies (CBO, 2013). In the absence of increased funding for public health overall, establishing eye and vision health as a stand-alone programmatic focus will require additional and dedicated resources beyond those currently available as well as technical support from federal public health entities and established partners.

Recommendation 8

To build state and local public health capacity, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention should prioritize and expand its vision grant program, in partnership with state-based chronic disease programs and other clinical and nonclinical stakeholders, to:

- Design, implement, and evaluate programs for the primary prevention of conditions leading to visual impairment, including policies to reduce eye injuries;

- Develop and evaluate policies and systems that facilitate access to, and utilization of, patient-centered vision care and rehabilitation services, including integration and coordination among care providers; and

- Develop and evaluate initiatives to improve environments and socioeconomic conditions that underpin good eye and vision health and reduce eye injuries in communities.

Grant opportunities offered to state health departments can be used in a variety of ways to support specific vision preservation activities in local

health departments or other organizations or encourage these activities as part of a more comprehensive strategy in partnership with other groups. Some states are actively encouraging a systematic community health assessment and planning process to be completed on a regular basis, and they can offer guidance and tools in what to look for in the community, available data sources that can be consulted in the assessment, and metrics for ongoing evaluation and quality assurance related to eye and vision health. Again, this recommendation emphasizes the need for a coherent and comprehensive program to account for primary prevention activities, for access and utilization of health care services to reduce vision impairment and improve function following vision loss, and for a focus on establishing environments that can affect the eye and vision health of a broader population.

The prioritization and expansion of the CDC’s vision grant program may require more than the provision of additional resources. Currently, VHI resides within the Division of Diabetes Translation (CDC, 2016). The committee has no opinion on the exact placement of VHI within the CDC. However, the organizational location should offer, for example, visibility, sufficient staffing, integration with other chronic disease activities, expertise in insurance coverage, surveillance, and policy and programmatic expertise. Furthermore, VHI should continue to integrate with other components of the CDC and work with state, local, and other stakeholders. This could enhance the capabilities to offer technical assistance, scientific bases for collaboration among stakeholders, aid in translating science into strategic activities, and advice on issues related to vision loss and vision impairment on a much larger scale than currently exists under VHI (CDC, 2015a).

PROMOTE COMMUNITY ACTIONS THAT ENCOURAGE EYE- AND VISION-HEALTHY ENVIRONMENTS

Living with vision impairment or having a loved one with uncorrectable vision impairment, especially when it is severe, has the potential to affect many aspects of everyday life and has been associated with a diminished QOL, including independence (see Chapter 3). Vision loss has

been associated with serious health comorbidities such as depression, anxiety, low self-esteem and insecurity, social isolation, stress, mental fatigue, cognitive decline and dementia, reduced mobility, falls, and mortality (see Chapter 3). The impact that vision loss has on function and QOL varies according to numerous factors, including the built environment, social support, access to health care and rehabilitation services, attitude, preferences, and socioeconomic factors. How these factors affect the occurrence, severity, and impact of vision loss differs for individuals and communities. This situation requires communities to engage in broad-based discussions with different stakeholders, including elected officials and public health departments, to determine how national level policies, data, and programs can be implemented at the local level.

Eye and vision health is a community issue—the needs, adequacy of resources, and priorities will vary based on population characteristics, cultures, and values. It is important that community stakeholders (businesses, advocacy organizations, neighborhood groups, local health and public health departments, religious organizations, professional organizations, school boards and faculty, parent support groups, health care providers, eye care providers, etc.) be actively consulted and engaged in options to translate and implement national goals into workable community action plans to reduce the burden of vision loss and the functioning of populations with vision impairment across different community settings.

Recommendation 9

Communities should work with state and local health departments to translate a broad national agenda to promote eye and vision health into well-defined actions. These actions should encourage policies and conditions that improve eye and vision health and foster environments to minimize the impact of vision impairment, considering the community’s needs, resources, and cultural identity. These actions should:

- Improve eye and vision health awareness among different social groups within communities;

- Engage community organizations and groups to promote eye and vision health awareness in daily activities;

- Establish and enforce laws and policies intended to promote eye safety and the functioning of people with vision impairment;

- Identify the need for, and community-level barriers to, vision-related services and resources in their communities; and

- Adopt policies and create community networks that support the design of built environments and the establishment of social environments that promote eye and vision health and independent functioning.

A key role for the governmental public health departments is to act as conveners of the different stakeholders who then develop and implement action plans that may complement national initiatives and that reflect a community’s needs and goals. Local health departments are a natural resource for communities (including, but not limited to, government agencies, elected officials, policy makers, local nonprofit organizations, community health centers, educators, religious organizations, employers, fraternal organizations, municipal sports leagues, and other stakeholder groups) to engage when exploring the needs and resources available to combat avoidable vision impairment and the impacts of vision loss in their communities. For example, health departments can play an important role in the built environment (i.e., the physical environment constructed by human activity) (e.g., Perdue et al., 2003). They are also uniquely positioned to bring together different stakeholders within communities to begin discussions about strategies to improve different community settings and environments (including the social, economic, and built environments) and how to measure the impact of community investment.

Communities must feel comfortable in expressing the values and goals that are most relevant to them, especially in the context of establishing local actions that respond to a national agenda. Depending on the characteristics of specific populations within those communities, some actions will be more or less relevant. For example, in communities with older populations, an emphasis on programs to improve the detection and treatment of age-related eye diseases and conditions may be more applicable. In communities with school-aged children and young adults, instituting visual acuity screenings and comprehensive eye examinations in schools and developing policies to promote wearing personal protective equipment may be more relevant.

Communities must also consider the broad range of factors that affect eye and vision health, including multiple determinants of health, when deciding not only what actions to take but also who should be involved in discussions that lead to decisions about priority actions. For example, strategies related to the built environment would benefit from input from local architecture firms and community planning experts, in addition to input from more traditional public health practitioners. Input could include identifying barriers and opportunities related to public awareness about the burden of poor eye and vision health; leveraging laws and policies designed to promote function; and utilizing resources drawn from a wide range of contributors (e.g., local religious organizations, nonprofit organizations, schools, workplaces, and sports leagues) to promote access to eye and vision services. It is important that these discussions be as broad and inclusive as possible and not to overlook the personal perspectives of

those with vision impairment in order to promote the kind of change that will eventually lead to new social norms concerning eye and vision health.

Community collaborations with public health departments should provide a safe venue in which to promote shared experiences and expertise, create effective platforms for communication, and develop action plans and program or initiative evaluations that contribute to both local and national dialogues and collective action. Public health departments could produce materials and informational resources based on member input, which could be used to facilitate action in other neighboring communities. For example, action strategies targeting different stakeholders and community needs would be more effective if these strategies were part of a comprehensive plan to improve eye and vision health statewide.

RECOMMENDATIONS IN ACTION: EXAMPLES FOR IMPLEMENTATION

“As an approach, population health focuses on the interrelated conditions and factors that influence the health of populations over the life course, identifies systematic variations in their patterns of occurrence, and applies the resulting knowledge to develop and implement policies and actions to improve the health and well-being of those populations” (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2007). To this end, the committee’s recommendations are visionary and are meant to set in motion a variety of broad-based actions that can contribute to the prioritization of eye and vision health at national, state, and local levels. This has the benefit of encouraging coordinated actions that can sustain a larger movement. But it also has drawbacks—most notably, it does not provide discrete, recommended actions for the range of stakeholders at every level and across every dimension of eye and vision health that are essential to the successful promotion of eye and vision health.

In Chapter 1, the committee proposed a model for action (see Figure 9-2), which suggested that the 10 essential health services of public health assessment, policy development, and assurance extended across four categories of prevention, including primordial, primary, secondary, and tertiary activities. The 10 services each are part of one of three core population health functions: assessment (i.e., monitoring communities to identify and characterize public health needs and priorities), policy development (i.e., the use of scientific evidence to guide the design and implementation of programs and policies to address public health issues), and assurance (i.e., policy development and enforcement, ensuring that health and public health systems have the resources to implement programs, and evaluating the health impacts of interventions) (CDC, 2007; IOM, 1988). In the context of eye and vision health and the committee’s charge, these actions

SOURCE: Adapted from CDC, 2014.

include short- and long-term strategies to address the overarching determinants of health (primordial prevention); efforts to support, educate, and promote healthy eye and vision behaviors (primary prevention); efforts to facilitate the pre-symptomatic identification of eye diseases and treatments (secondary prevention); and efforts to preserve and enhance the health and functioning of individuals with vision impairment (tertiary prevention).

The committee’s recommendations are broad, intended to promote competencies and foundational evidence that can advance long-term improvements in eye and vision health in the United States. The challenges facing eye and vision health in the United States, particularly those associated with identified research gaps, the resources to establish eye and vision health as a public health programmatic focus, the formation of partnerships, and guidelines to inform the public about necessary services, will require a long-term commitment to promote competencies and foundational evidence that can guide specific action in the future.

To complement this approach, the committee also developed a stakeholder action table (see addendum to this chapter) to provide illustrative examples of activities that could logically flow from the committee’s much broader recommendations. These actions are organized by key stakeholder groups, which include payers, professional groups, patient advocacy groups, state and local public health departments, private industry, community groups, and federal agencies, particularly the CDC and the National Institutes of Health. Within these groups, there are actions related to assessment, policy development, and assurance across the four stages of prevention: primordial, primary, secondary, and tertiary (see Figure 9-2); and many could easily be classified in other categories. The examples provided are not recommendations per se. Rather they are meant to stimulate discussion among stakeholders about the potential actions stakeholders can take by public health function and stages of prevention as part of a comprehensive and cohesive approach to improve eye and vision health and reduce health inequities in the United States.

CONCLUSION

Vision impairment is a significant public health problem that affects the health, economic well-being, and productivity of individuals, families, and society as a whole. The focus of population health approaches to eye and vision health should be on creating the conditions in which people can have the fullest capacity to see and that enable individuals to achieve their full potential. Despite evidence that vision impairment increases the risk of mortality and morbidity from other chronic conditions and related injuries and is associated with a reduced QOL, eye and vision health is

not adequately recognized as a population health priority, so public health action has been extremely limited.

Achieving the twin goals of improving eye and vision health and increasing health equity will require action by a wide range of stakeholders at the national, state, and local levels. In the context of eye and vision health and the committee’s charge, these actions will need to include short- and long-term strategies to address the overarching determinants of health (primordial prevention), as well as efforts to support, educate, and promote healthy eye and vision behaviors (primary prevention); to facilitate pre-symptomatic identification of eye diseases and treatments (secondary prevention); and to preserve and enhance the health and functioning of individuals with vision impairment (tertiary prevention).

To effectively promote eye and vision health and reduce vision impairment, sustained action across all stakeholders and levels of government will be necessary. It will require (1) better and constant surveillance; (2) policy, program, and funding incentives to stimulate and reinforce the adoption of best practices; (3) constant quality improvement experiments in all sectors in the area of vision health to discover and disseminate what works and what does not; (4) research to discover new means of prevention, rehabilitation, and treatment; (5) changes in personal and professional behavior and their surrounding systems so that they no longer reinforce current problems and instead constantly reinforce and reward making the right and best things the easiest things to do; (6) education and training for current and future workforces to improve behavior and practice; and (7) a change in political dynamics at the local, state, and federal levels to give priority once again to a broadened sense of “national and personal responsibility.” Anchoring eye and vision health promotion in terms of prevention stages will allow the nation to reevaluate eye and vision health improvement as not only a valued outcome in and of itself, but also a strategy by which to achieve better health equity more broadly among populations.

REFERENCES