1

Introduction

Avoidable vision impairment occurs too frequently in the United States and is the logical result of a series of outdated assumptions, missed opportunities, and manifold shortfalls in public health policy and health care delivery. The ability to see affects how human beings perceive and interpret the world. The sense of sight is critically important to an individual’s communication, physical health, independence and mobility, social engagement, educational and employment opportunities, socioeconomic status, and performance of daily activities, such as reading, driving a car, and caring for family members (Alberti et al., 2014; Bowers et al., 2009; Bronstad et al., 2013; Brown et al., 2014; Rahi et al., 2009; Sengupta et al., 2014; Whitson et al., 2007, 2014; Wood et al., 2012). Uncorrectable vision impairment can lead to a progressive inability to participate in family, social, and community activities and is associated with a higher prevalence of chronic health conditions, death, falls and injuries, social isolation, depression, and other psychological problems (Court et al., 2014; Crewe et al., 2013; Crews et al., 2016a,b; Kulmala et al., 2008, 2012; Lord, 2006; Rees et al., 2010; van Landingham et al., 2014). In early childhood, any condition that prevents an eye from focusing clearly (e.g., misalignment of the eyes, pronounced differences in refractive error between the two eyes, or obstruction or deformation of the light into the eye) may result in physiological alterations to the visual pathway that can lead to ongoing visual impairments (Birch, 2013; Davidson and Quinn, 2011). This can significantly affect an infant’s or child’s development and health, restricting participation in social, physical, and educational activities and, later, employment opportunities (Davidson and Quinn, 2011).

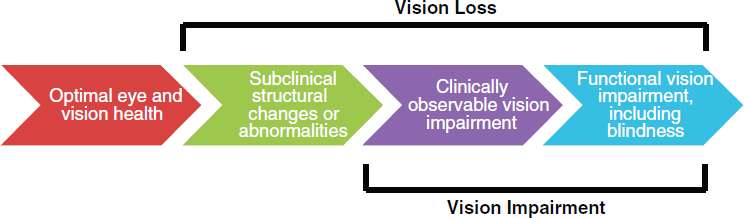

Vision loss,1 the process by which physiological changes or damage to the structure of the eye or visual information processing structures in the brain occurs, results in compromised subclinical or clinical function of the eye or visual processing system. Vision loss may occur suddenly and completely, for example from injury, or may subtly evolve over time, with permanent structural damage leading to progressive changes in eye function until more pronounced deficits become noticeable. Vision impairment, defined in this report as a measure of the functional limitation of the eye or visual system that results from vision loss, remains an unmet and important public health threat and is largely attributable to a few conditions or diseases in the United States.

No reliable data exist on the number of people affected by all causes of vision impairment in the United States. One model, based on a review of 12 major epidemiological studies and the 2010 U.S. Census population, estimates that approximately 90 million of the 142 million adults over the age of 40 in the United States experienced vision problems attributable to vision impairment, blindness, refractive error (i.e., myopia and hyperopia), age-related macular degeneration (AMD),2 cataract, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma (Prevent Blindness, 2012a).3 Refractive error alone affected more than 48 million people over age 12 in the United States (Prevent Blindness, 2012c). Presbyopia, an age-related condition that affects the ability to focus clearly on near objects, affects almost everyone entering the middle-age years (Petrash, 2013). As demographic trends change (i.e., the “silver tsunami”) in the United States, the prevalence of all forms of vision impairment is also projected to increase (Varma et al., 2016). Actions to evaluate, monitor, and protect eye and vision health should begin early in life, but the systems and policies to encourage these behaviors in a fair and equitable manner are lacking.

The prevalence of vision loss, as well as the severity of subsequent vision impairment, varies across geographic areas by etiology, age, race and ethnicity, and gender, putting certain populations at higher risk for specific types of vision loss (Congdon et al., 2004; Kirtland et al., 2015; Qiu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2012). Increased risk for poor eye and vision health is also associated with broader social, economic, cultural, health, and environmental conditions, which may contribute to greater overall health disparities (Cumberland et al., 2016; Ulldemolins et al., 2012; Zambelli-Weiner et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). Conversely, the promotion of

___________________

1 The committee adopted these definitions of vision loss and vision impairment to help facilitate discussion of eye and vision health in the context of population health. Justifications for these definitions are discussed in this chapter.

2 The estimate for AMD includes individuals age 50 and older.

3 This statistic was corrected following release of the prepublication copy of the report.

eye and vision health may positively influence many other social ailments, including poverty, increasing health care costs, and avoidable mortality and morbidity (Christ et al., 2014; Kirtland et al., 2015; Lee, 2003; Rahi et al., 2009; Rein, 2013). Identifying high-risk populations for certain types of vision loss can help target limited resources, tailor effective interventions, and promote policies that better achieve eye and vision health and improve population health equity.

The economic impact of chronic vision loss on individuals and society is substantial. One national study commissioned by Prevent Blindness found that direct medical expenses, other direct expenses, loss of productivity and other indirect costs for visual disorders across all age groups were approximately $139 billion in 2013 dollars (Wittenborn and Rein, 2013), with direct costs for the under-40 population reaching $14.5 billion dollars (Wittenborn et al., 2013). Time spent by caregivers also increases substantially as vision decreases, averaging between 5.8 hours per week and 94.1 hours per week for persons with vision impairment, depending on the severity of vision loss (Köberlein et al., 2013). Moreover, chronic vision loss can amplify the adverse effects of other chronic illnesses and is associated with an increased risk for all-cause and injury-related mortality (Christ et al., 2014; Crews et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2002, 2003). Yet as a chronic condition, vision impairment is rarely supported as a categorical focus or even as part of chronic disease programs (e.g., a single eye health metric) in most state and local health departments because of resource limitations and competing priorities.

Some of the most notable successes in preventing vision loss have been anchored in population health strategies (e.g., CDC, 2015b; Kumaresan, 2005; Rao, 2015). Preventing injury, infection, and underlying chronic disease could have substantial effects on protecting or maintaining eye and vision health. For example, estimates suggest implementing policies that better encourage the use of protective eyewear could reduce work- and sports-related eye injuries by as much as 90 percent (Dang, 2016). Similarly, programs designed to reduce the prevalence of diabetes would also necessarily reduce the prevalence and incidence of diabetic retinopathy.

Early diagnosis and appropriate access to high-quality treatment could improve the trajectory of modifiable or correctable vision impairment by either slowing the progression of specific diseases or conditions or correcting the vision impairment itself. Uncorrected vision impairment (i.e., the proportion of overall vision impairment that could be improved through currently available treatments) may represent the clearest opportunity to improve eye and vision health in the United States based on current knowledge and the relative effectiveness of specific treatments. Millions of people over the age of 12 years live with uncorrected refractive error in the United States, with estimates ranging anywhere from 8.2 million (Varma et al.,

2016) to 11.0 million (CDC, 2015d) to 15.9 million (Wittenborn and Rein, 2016).4 Similarly, cataracts are largely treatable, yet vision impairment from uncorrected cataracts remains problematic, especially for certain minority populations (Shahbazi et al., 2015; Sommer et al., 1991; Wittenborn and Rein, 2016). Programs and payment policies targeting access to appropriate screenings, comprehensive eye examinations,5 and follow-up care (including coverage of corrective lenses) could improve eye and vision health, especially among populations with lower economic status and poor health.

Uncorrectable vision impairment (i.e., the amount of vision impairment that remains after appropriate treatment or intervention)6 affects approximately 4.2 million adults over the age of 40 (Prevent Blindness, 2012a; Varma et al., 2016) and another 2.155 million children and adults under age 39 each year in the United States (Wittenborn et al., 2013).7 Prevalence in the over-40 population is projected to rise to 8.96 million by 2050, as demographic trends change (i.e., the coming of the “silver tsunami”) in the United States (Varma et al., 2016). Information about, and access to, interventions that can improve or maintain the function of people with vision impairment are often limited (Overbury and Wittich, 2011; Walter et al., 2004). Population health approaches targeting uncorrectable vision impairment often focus on improving functionality, productivity, and independence through access to visual assistive devices, vision rehabilitation services, and reasonable accommodations—although earlier access to effective treatments may prevent the progression of modifiable to uncorrectable vision impairment for certain conditions and diseases.

This report proposes a conceptual framework to advance eye and vision health as a population health priority among various—and sometimes competing—stakeholders in pursuit of improved eye and vision health

___________________

4 The committee commissioned an analysis, which was not available in the current literature, to establish the preventable burden of vision impairment in the United States from five conditions (diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, refractive error, cataracts, and AMD). Estimates are based on a variety of sources (including population surveys and compilations of population-based studies) and reflect the best available public data. The committee presents only the results related to cataracts and uncorrected refractive error in this report because the analyses are most robust for these conditions. Chapter 3 provides a more in-depth description of the study’s assumptions and limitations, which are also documented in the commissioned paper itself (Wittenborn and Rein, 2016). This citation was added post release.

5 For this report, the committee defines a comprehensive eye examination as a dilated eye examination that may include other tests.

6 Uncorrectable vision impairment is often defined in terms of visual acuity (e.g., Prevent Blindness, 2012b; Varma et al., 2016).

7 These figures combine estimates for vision impairment and blindness. Each of these studies defines vision impairment and blindness separately and in terms of visual acuity in the best corrected and better seeing eye (Prevent Blindness, 2012b; Varma et al., 2016, p. E3; Wittenborn and Rein, 2016).

and health equity in the United States. This report also introduces a model for action that highlights different activities that a range of stakeholders must undertake and provides specific examples of how population health strategies can be translated into cohesive action at federal, state, and local levels. Initial public- and private-sector investment has helped identify the chief information gaps and provided a more nuanced understanding of the connection between eye and vision health and other measures of overall health, but more is needed. Implementing a coherent and comprehensive response to address the burden of vision loss will be challenging, but it is achievable.

STATEMENT OF TASK AND SCOPE OF STUDY

In 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Eye Institute (NEI), along with the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the American Academy of Optometry, the American Optometric Association, the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, the National Alliance for Eye and Vision Research, the National Center for Children’s Vision and Eye Health, Prevent Blindness, and Research to Prevent Blindness asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to conduct a consensus study on the current and potential roles of public health in addressing the burden of blindness and vision impairment, and the conditions, diseases, and injuries that cause them. Specifically, the Committee on Public Health Approaches to Reduce Vision Impairment and Promote Eye Health was asked to characterize the public health burden of major eye diseases, as well as the state of surveillance systems used to measure this burden; to examine existing models of vision care and eye disease prevention; to identify evidence-based health promotion interventions for vision care and encourage their development and utilization; and to develop strategies to promote collaboration among stakeholders in vision care in order to reduce the burden of low vision through the coordinated deployment of public health resources (see Box 1-1).

To respond to this task, the National Academies convened a committee of 15 experts with experience in population health and epidemiology, ophthalmology, optometry, health economics, gerontology, pediatrics, health disparities and behaviors, health law and policy, public policy and public–private partnerships, consumer and research advocacy, vision rehabilitation, and the care of complex, chronic disability (see Appendix A for the committee biographies). In addition to reviewing relevant literature, the committee held five meetings, including two public workshops and one public session (see Appendix B for the workshop agendas) to obtain input from an array of experts and stakeholders who informed the committee’s deliberations and final report. Throughout the course of this study, report

sponsors provided substantial cooperation, support, and responsiveness as the committee sought additional information for its deliberations.

Given the broad range of activities and partnerships explicitly mentioned in its charge, the wide array of current practices in eye care delivery, and the range of factors that can influence eyesight, the committee interpreted its statement of task as requesting it to target “population health” approaches, and the committee uses this term throughout this report. The term “public health,” which is often interpreted as being restricted to the actions of federal, state, and local health departments, is used in the context of governmental public health agencies.

It is important to note that the committee was not charged with defining appropriate scope of practice for various eye care professionals or endorsing specific clinical practice guidelines for various diseases and conditions. The report discusses these topics only in the context of needing consensus when ambiguity or inconsistency affects clear communication and makes it unclear what care should be provided, when, and by whom. The topic is also discussed when identifying key areas where additional evidence is needed.

CORE PRINCIPLES

To respond to its statement of task and anchor its analysis, the committee identified eight core principles to guide sustainable actions that can improve eye and vision health and health equity in the United States:

- Adequately Resourced. Resources must be available to allow communities to translate clinical and population health research findings into evidence-based practice in communities.

- Collaborative. The promotion of eye and vision health and environments outcomes will require cooperation, participation, and responsibility on the part of the public and institutional stakeholders (government, business, employers, the public, health care providers, and others).

- Community Tailored. Eye and vision health is local. The priorities and interventions related to vision impairment and population health must be assessed according to individual communities needs, resources, and values.

- Culturally Competent. The clinical and public health workforces must be adequately educated and trained to support eye and vision health in culturally diverse communities.

- Evidence-based. Community-based and clinical interventions to improve eye and vision health must be evidence-based in order

-

to establish efficacy as well as to gather information with which to guide other communities.

- Integrated. Eye and vision health should be integrated into current and future population health initiatives.

- Population-centered. In order to be effective policies and actions to improve population eye and vision health should support and respect the needs, identity, dignity, and circumstances of those populations being served.

- Standardized. Efforts to improve eye and vision health must be based on a common language that can help to unite stakeholders and make it easier to aggregate surveillance and research datasets.

DEFINITION OF KEY TERMS IN EYE AND VISION HEALTH

Various terms are used throughout the literature to signal different types and severities of vision impairment. Inconsistent definitions make it difficult to search for and compare relevant literature, and they also create confusion in trying to explain the nature, scope, impact, and treatment of eye and vision health. In fact, when conducting literature searches related to eye and vision health, the committee had to include a wide array of terms such as vision loss, vision impairment, visual impairment, blindness, eye health, vision health, and low vision (in addition to specific diseases or conditions) in an attempt to capture all relevant studies.

Even specific terms may not be defined or measured consistently. For example, although historically the term “low vision” has referred to some presentation of the visual system or range of vision outside of what may be considered “normal,” the term continues to be used in many different ways by different stakeholders. The NEI defines low vision as a visual impairment that is not correctable by standard eyeglasses, contact lenses, medication, or surgery and that interferes with the ability to perform everyday activities (NEI/NIH, 2008). In the context of rehabilitation services, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services defines “low vision” as a best-corrected visual acuity of less than 20/60 in the better-seeing eye, including diagnosis codes ranging from “moderate visual impairment” (less than 20/60) to “total blindness” (no perception of light) as well as visual field defects, such as hemianopsias, generalized constriction, and central scotomas, as listed in the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition–Clinical Modification Manual (ICD-9) (AHRQ, 2004). During the past decade, the term “vision impairment” was introduced with the intention of replacing the term “low vision” to better describe the continuum of eye and vision problems and subsequent vision loss (Dandona and Dandona, 2006).

Similarly, some studies define “blindness” as the “total loss of sight,” or the inability to perceive any light (i.e., no light perception) (e.g., Bastable,

2016, p. 307; Joseph and Robinson, 2012, p. 21). However, “statutory blindness” under U.S. Social Security laws is defined as “central visual acuity of 20/200 or less in the better eye with the use of a correcting lens” and/or when the “widest diameter of the [eye’s] visual field subtends an angle no greater than 20 degrees.”8 The World Health Organization defines blindness as best corrected visual acuity of less than 20/400 in the better-seeing eye (WHO, n.d.). Regardless of the differences in the acuity threshold, many studies and organizations have criticized both approaches because defining blindness in terms of “best corrected” means that policy makers, public health officials, and health care leaders may overlook a large number of persons with vision impairment who technically could correct their vision problems, such as refractive error, but may not practically be able to do so for various socioeconomic reasons (WHO, n.d.). Another group that may be overlooked are persons whose vision is significantly compromised in other aspects that do not affect visual acuity (e.g., visual processing), described later in this chapter. The committee agrees with the argument that these definitions of blindness leave out many people with visual impairments who should be considered as blind, and it supports efforts to revise this definition under the ICD-10.

To provide greater clarity and consistency in its analysis and recommendations throughout this report, the committee defined specific key terms, which are provided in Table 1-1 along with functional descriptions. The committee chose to define “vision loss” as a process because it emphasizes the importance of approaching vision impairment as the result of a series of decisions, exposures, or circumstances—many of which can potentially be altered to affect the trajectory of the severity of vision impairment across the lifespan. This definition is meant to encourage people to step back and consider the promotion of eye and vision health, rather than simply the treatment of observable eye conditions and diseases. Similarly, vision impairment was defined broadly as a measure of the type and severity of vision loss, which includes blindness. As a general matter, optimizing the eye and vision health of a population should not be based on artificial segmentations of populations as defined by observed outcomes. When analyzing the impact and severity of vision impairment by race, ethnicity, gender, age, and geographic unit, among other risk factors, it is important to track and consider the full range of vision impairment (including uncorrectable and uncorrected) associated with a disease, condition, or event because it can reveal opportunities to reduce inequities. Moreover, categorizing populations based on the severity of vision impairment unnecessarily divides a constituency that must be united to advocate for necessary changes to

___________________

8 Social Security Act § 216(i)(1)(B).

TABLE 1-1 Definitions of Key Terms Related to Eye and Vision Health

| Term | Clinical Definition | Functional Description |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic vision impairment | A vision impairment that is present and must be managed over the lifespan to maintain the activities of daily living. | A vision impairment whose causes or effects cannot be reversed or eliminated by corrective lenses,a medication, or surgery. As a result, health care interventions will be necessary over the course of a person’s life. |

| Comprehensive eye examination | A dilated eye examination that may include a series of assessments and procedures to evaluate the eyes and visual system, assess eye and vision health and related systemic health conditions, characterize the impact of disease or abnormal conditions on the function and status of the visual system, and provide treatment and follow-up options. | An in-person clinical encounter between an eye doctor and an individual intended to diagnose and treat any eye disease or condition that might lead to visual impairment, reduce visual function or eye discomfort, and connect the person with other needed clinical and nonclinical services to improve or maximize personal independence and promote health. The dilated eye examination may lead to referrals for other health care and nonclinical services or suggest future eye and vision care to avoid or slow progression of vision impairment. |

| Eye and vision health | Creating the conditions where people can have the fullest capacity to see and that enable them to achieve their full potential. | |

| Legal blindness (as defined in the United States) | Visual acuity of 20/200 or less in the better eye with the best possible correction and/or a visual field of 20 degrees or less.b | A person sees at 20 feet what a person with normal vision sees at 200 feet, and/or a person sees a visual field of 20 degrees or less in the better field. |

| Total blindness | Total loss of sight | The inability to perceive any light; e.g., total visual impairment. |

| Vision impairment | A measure of the type and severity of clinical or functional limitation of one or both eyes or visual information processing structures in the brain. | A measure of the type and severity of limitations in vision, including blindness. Vision impairment can range from mild to total (blindness) and can range from impairments in visual acuity to visual field to other aspects of the eyes and/or visual system. |

| Term | Clinical Definition | Functional Description |

|---|---|---|

| Vision loss | The process by which physiological changes or structural, neurological, or acquired damage to the structure or function of one or both eyes or visual information processing structures in the brain occurs, resulting in vision impairment. | The process by which eyesight deteriorates. A loss of sight can be affected by many different structures or functions within the eye or brain (see Chapter 2), which can affect one or more dimensions of eye and vision health. In many cases, individuals do not notice the changes that occur until their inability to see begins to affect every day activities. Vision loss is often chronic, progressive, and/or irreversible. |

| Vision screenings | A tool that allows for the possible identification, but not diagnosis, of eye disease and conditions. | A method to identify potential problems or irregularities with the visual system so that a referral can be made to an appropriate eye care professional for further evaluation and treatment. |

| Visual acuity | A number that indicates the sharpness or clarity of vision, measured by the ability to discern objects at a given distance according to a fixed standard. | A measure reflecting the distance between the eye and an object at which the object becomes blurry. Visual acuity is a term used to describe the quality of the image perceived. |

| Visual field | The total area an individual can see off to the side without moving the eye. | Visual field is a term used to describe the “window” that each eye provides to see the world. Visual field describes the extent of the visual system’s window on our environment. It can be used to describe partial or total impairments within the window through which we see the world, and is a component of the visual system that is used in determining legal (statutory) blindness and, often, driver’s licensure eligibility. |

a The committee has defined a corrective lens as “a lens worn in front of the eye, usually to correct a refractive error. Examples of corrective lenses include glasses (which include lenses and frames) and contact lenses” (see Appendix C).

b Social Security Act § 216(i)(1)(B).

advance eye and vision health and reduce the impact of different types and severities of vision impairment, as described throughout this report.

The committee recognizes that it is necessary to distinguish between individuals with less severe vision impairment from those who are blind (however this is defined) for the enforcement of specific regulations and policies, such as disability law and Medicare payment policies, and for specific surveillance purposes and programmatic emphasis. The committee did not attempt to define the contexts in which specific clinical definitions of specific diseases or severity of vision loss should be used, although the committee notes that inconsistencies across policies, programs, and studies require additional attention.

The continuum of eye and vision health (see Figure 1-1) includes the maintenance of good eye and vision health, as well as the prevention or mitigation of vision loss. It is a continuum that highlights subclinical and observable processes to yield important points of intervention for population health strategies that are aimed at reducing or delaying a wide range of vision impairments and related consequences.

The most effective policies and interventions take into account the specific etiology and causation of vision loss as well as the availability of treatments or therapies for resulting vision impairment. It is worth noting that the term “vision loss” has been applied to the circumstances in which an individual has experienced a deleterious change from some previous visual ability and that it implicitly recognizes the sense of “loss” associated with such a decline in vision. By contrast, an individual with congenital or very early-life blindness may not perceive vision impairment as a loss, which will affect that individual’s level of interest in—and willingness to accept—treatments meant to reverse or treat vision impairment. It is important to note that when the committee uses “vision loss” it does not imply that the impairment has been acquired (as opposed to congenital), but rather the committee equates vision loss with the underlying physiological processes associated with sight.

Types of Vision Impairment

The degree of vision impairment is characterized by a variety of diagnostic measures, which are affected by numerous diseases and conditions described in greater detail in Chapter 2. The public is probably most familiar with visual acuity tests, which are often associated with identifying letters or symbols on a chart (e.g., a Snellen chart) that become progressively smaller until the letters or symbols are no longer legible to the patient. The resulting fraction (e.g., 20 over 20, 20 over 600) compares the vision of a given individual with that of a person with normal vision; an individual has 20/50 vision, for example, if he or she can make out an object at a distance of 20 feet that a person with normal vision can make out from 50 feet; the ratio is representative of the clarity of a visual image perceived by that individual (NLM, 2016). Table 1-2 provides a description and examples of how different visual acuities could affect functional ability. These interpretations are not standardized across populations and should not be interpreted to mean that two people with the same measured acuity will see the same thing. However, it is important to have a general understanding of how visual acuity loosely translates into measures of function and the population health burden of vision impairment, especially in the context of uncorrected refractive error.

Serious vision impairments can also manifest as problems with contrast sensitivity, visual field loss (i.e., loss of part of the usual visual field), seeing two images (i.e., double vision), extreme sensitivity to light (i.e., photophobia), visual distortion (e.g., blind spots, haloing around an object or light), color blindness, visual perceptual difficulties, or any combination of these conditions. The impact that different aspects of vision have on daily function varies. For example, color blindness affects one’s ability to select matching clothes, distinguish different driving signs and signals, or join the Air Force. Significant visual acuity problems make it difficult to see objects in one’s house or to navigate city streets or sidewalks safely. Decreasing peripheral vision can result in tunnel vision, which can affect the ability to see things around a person and can create problems with driving or cause one to run into stationary obstacles (e.g., doorframes) while walking. Problems with contrast sensitivity can make it difficult to interpret the significance of different types of shading (e.g., shadows versus stairs), read poorly contrasted text on posters or classroom slides, to move comfortably from a bright to a dark environment or vice versa, or to perceive the presence of an object in front of a similarly shaded background. For a vast majority of people with these conditions, the resulting vision impairment is continuously present and must be managed over the lifespan, which has important implications for public policies concerning health care delivery, community

TABLE 1-2 Description of Functional Ability Based on the Snellen Chart

| Snellen (“Customary”) Distance Visual Acuity | Level of Vision Impairment | How Might My Vision Change If Uncorrectable?a | Examples of Patient Outcomes at This Levelb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20/10 to 20/25 | Range of normal vision | NA | NA |

| 20/30 to 20/60b,c | Near-normal vision |

|

|

| 20/70 to 20/160 | Moderate visual impairment |

In addition to the above…

|

In addition to the above…

|

| Snellen (“Customary”) Distance Visual Acuity | Level of Vision Impairment | How Might My Vision Change If Uncorrectable?a | Examples of Patient Outcomes at This Levelb |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| 20/200 to 20/400 (and/or visual field limitation of 20 degrees or less in better eye) | Severe visual impairment; includes “legal blindness” |

In addition to the above…

|

In addition to the above…

|

| 20/500 to 20/1,000 | Profound visual impairment |

In addition to the above…

|

In addition to the above…

|

| Snellen (“Customary”) Distance Visual Acuity | Level of Vision Impairment | How Might My Vision Change If Uncorrectable?a | Examples of Patient Outcomes at This Levelb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acuity less than 20/1,000 Includes hand motion, light projection, and light perception (and/or visual field of 5 degrees or less in better eye) | Near total visual impairment |

In addition to the above…

|

In addition to the above…

|

| No light perception | Total visual impairment; i.e., blindness |

|

|

a Changes in vision and function are common examples, but may not be the same across individual patients.

b Early changes and/or fluctuations in visual acuity in this range are often ignored and may go unnoticed.

c Changing customary spectacle or contact lens prescriptions, as well as surgical and/or pharmaceutical intervention(s), does not fully restore visual acuity to the normal range normal range. Exceptions include prescription of lenses for uncorrected refractive error and surgical removal of cataract, both of which customarily provide improvements in visual acuity.

SOURCE: Adapted from AOA, 2007.

design, messaging for public awareness and education campaigns, health professional education, and research prioritization and support.

A POPULATION HEALTH APPROACH TO IMPROVE EYE AND VISION HEALTH AND REDUCE VISION IMPAIRMENT

It is easy to overlook (and perhaps forget) that some of the most notable successes in preventing vision loss have been anchored in population health strategies. International blindness prevention programs have significantly reduced blindness from diseases such as vitamin A deficiency and onchocerciasis (i.e., river blindness) (Rao, 2015). In the United States, the enforcement of regulations aimed at promoting safe workplaces by the

Occupational Safety and Health Administration and efforts to improve the standardization of personal protective equipment (including safety glasses) through such federal entities as the National Personal Protective Technology Lab have vastly reduced occupational eye injuries, although more improvement is needed (BLS, 2012; CDC, 2015e). Trachoma, once widespread and a reason for denying entry to infected immigrants, is now virtually eliminated in the United States (Kumaresan, 2005). Gonococcal conjunctivitis is also now rarely seen in newborns, as most hospitals are required by state law to apply antibiotic drops or ointment to a newborn’s eyes to prevent the disease (CDC, 2015b). Still, eye and vision health remains important in the context of some communicable diseases, such as the Ebola or rubella viruses, which can, respectively, remain in the eye for significant periods of time or affect the developing vision system of unborn children (CDC, 2015c; Varkey et al., 2015). Beyond vision loss itself, eye and vision health can also serve as an indicator for other chronic conditions, such as diabetes or multiple sclerosis, and of brain tumors, particularly those affecting the pituitary gland (Crews et al., 2016b; Frohman et al., 2008; Prasad, 2013). Unfortunately, many health-related policies and practices still reflect antiquated positions that do not adequately reflect the connection between eye and vision health (along with other sensory organs) and the promotion of overall health.

During the past few decades, many experts and policy makers have argued for a broader approach to improving the eye and vision health of the nation. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the NEI, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), and the World Health Organization (WHO) have defined vision impairment and blindness as national or global public health problems.9 The CDC has also identified vision loss as a public health problem, funding a variety of activities to combat the effects of poor eye and vision health on at-risk populations.10 In 2007 the CDC published the report Improving the Nation’s Vision Health: A Coordinated Public Health Approach, which identified three key public health activities: assessment (surveillance and epidemiology), application

___________________

9 Healthy People 2020, a project of HHS through the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, lists vision loss as a major public health concern (HHS, 2015). The NEI has called vision loss a major public health problem (NEI/NIH, 2004). WHO identifies blindness and vision impairment, and the diseases that cause them, as public health problems (WHO, 2015a). The USPSTF identifies impairment of visual acuity as a serious public health problem among older adults (USPSTF, 2009).

10 Per the CDC, there are five definitional features of a public health problem: (1) the problem affects a large number of people; (2) the problem imposes large morbidity, quality of life, and cost burdens; (3) the severity of the problem is increasing and is predicted to continue increasing; (4) the public perceives the problem to be a threat; (5) community or public health-level interventions to the problem are feasible (CDC, 2009b).

(applied public health research), and action (integrating vision health into programs and policy) (CDC, 2007). The report also proposed eight core elements to improve the nation’s health: engaging key national partners, collaborating with state and local health departments, implementing vision surveillance and evaluation systems, eliminating eye health disparities by focusing on at-risk populations, integrating vision health interventions into existing public health programs including systems and policy changes that support vision health, addressing the role of behavior in protecting and optimizing vision health, assuring professional workforce development, and establishing an applied public health research agenda for vision. Following the release of that report, the CDC launched the Vision Health Initiative (VHI) to promote vision health and quality of life for all populations, throughout all life stages, by preventing and controlling eye disease, eye injury, and vision loss resulting in disability (CDC, 2015a). Many of the recommendations and actions included in the 2007 report and in various VHI activities are discussed in this report—these are important concepts.

Despite these efforts, eye and vision health remain notably absent as a population health priority in the overarching public health and health care systems. It is also underrepresented in strategic plans that address the impact of chronic diseases and conditions within the United States. This has resulted in having insufficient evidence to guide decisions about policies that affect resource allocation to advance research, health care and rehabilitation service delivery, public health priorities and interventions. It has also impeded opportunities to emphasize efficiency, value, and the role of collaboration in improving the eye and vision health—a critical aspect of overall health—for general and patient populations.

Multiple Determinants of Eye and Vision Health

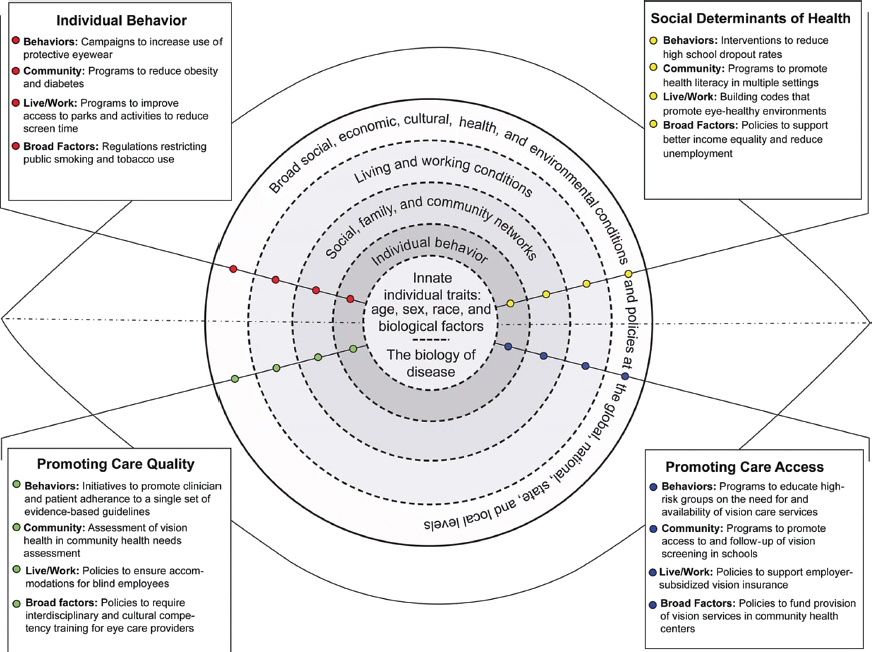

Eye and vision health of individuals and populations are affected by multiple determinants, including (1) innate individual traits (e.g., age, sex, race, and biological factors); (2) individual behaviors; (3) social, family, and community networks; (4) living and working conditions; and (5) broad social, economic, cultural, health, and environmental conditions and policies, which are each part of larger social and physical environments (IOM, 2003). Some of these determinants are modifiable, whereas others are not. For example, in the context of eye and vision health, genetics and the aging process itself may predispose populations to specific types of eye diseases and conditions. Conversely, exposure to ultraviolet sunlight, which is associated with an increased risk of cataracts, can be mitigated through the use of protective eyewear or window tinting.

Interactions among determinants of health may have impacts at the community or individual level, and understanding the relationships among

these determinants is important to achieving the greatest benefit. Lower socioeconomic status can limit access to healthy living environments and also to health care services. Food policies may contribute to the obesity epidemic, which is linked to the other chronic conditions, such as diabetes, which affect the eyes. It is important to note that, within this approach, health care services are only one component of the “living and working conditions” that affect health. The majority of health determinants exist outside the clinical care system (Braveman and Gottlieb, 2014; McGinnis et al., 2002), which provides a wide range of opportunities and environments in which vision health can be influenced. Figure 1-2 provides examples of specific risk and protective factors by health determinant category, which may be the targets of a broad population health approach to improving eye and vision health across the lifespan. Many other examples are provided throughout this report.

A Conceptual Framework to Bridge Public Health and Clinical Approaches to Eye and Vision Health

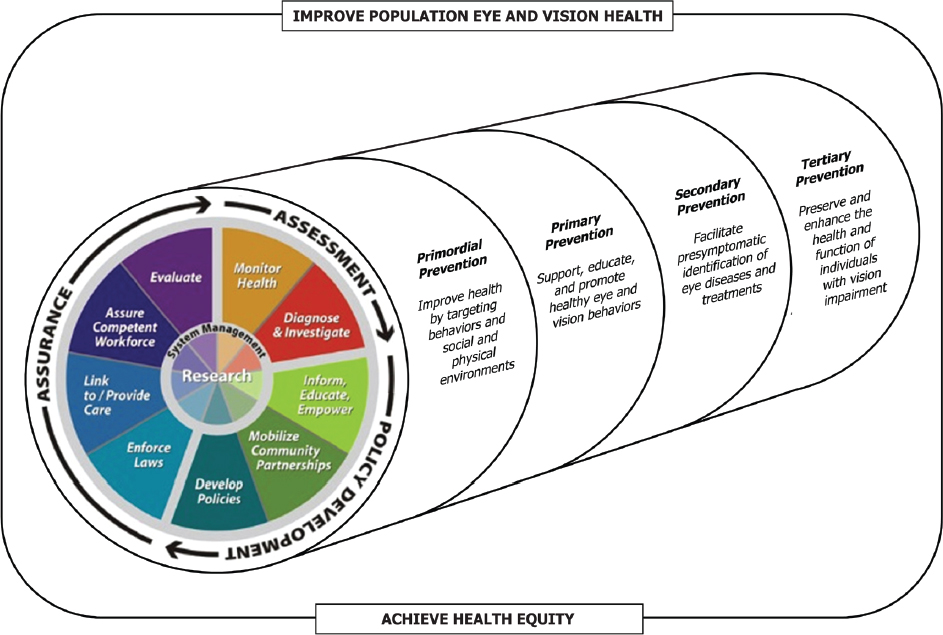

“[Public health’s] purpose is to monitor and evaluate health status as well as to devise strategies and interventions designed to ease the burden of injury, disease, and disability and, more generally, to promote the public’s health and safety” (Gostin et al., 2007, p. 7). More generally, the purpose of public health is to create the conditions whereby people can be healthy and achieve their full potential (WHO, 1986). This purpose is advanced through three population health functions: (1) assessment (i.e., monitoring communities to identify and characterize public health needs and priorities), (2) policy development (i.e., the use of scientific evidence to guide the design and implementation of programs and policies to address public health issues), and (3) assurance (i.e., policy development and enforcement, ensuring that health and public health systems have the resources to implement programs, and evaluating the health impacts of interventions) (CDC, 2007; IOM, 1988). Each function comprises 10 essential public health services, as developed by the Core Public Health Functions Steering Committee more than two decades ago (CDC, 2014). Box 1-2 presents these services in the context of eye and vision health. These services represent a full spectrum of activities and are part of a continuous process, which is centered around ongoing research to generate new knowledge that informs decision making and future iterations of interventions and initiatives.

In contrast to clinical care, which focuses on treating individual patients, population health systems concentrate on health risks to populations, addressing underlying determinants of health that affect not only specific health outcomes but also the circumstances that allow populations to make healthy choices and live in healthy environments. Because population

SOURCE: Adapted from IOM, 2003, p. 52.

health focuses on all determinants of health, the responsibility for improving population health has never been the sole province of any one actor or stakeholder. Implementing a population health approach for eye and vision health requires a robust effort and collaboration from multiple stakeholders, including government agencies, businesses, the community, health care providers, the media, and academia (IOM, 2003, 2011).

In the context of eye and vision health, a large amount of attention has focused on the access to and utilization of health care services, which is not typical of many other population health initiatives, such as efforts to combat obesity or reduce tobacco use. However, early and appropriate access to eye care and rehabilitation services will be an important component of any comprehensive population health approach to reduce the severity of vision impairment and the impact of vision impairment on quality of life. For example, comprehensive eye examinations may help identify eye and vision diseases and conditions before a patient notices symptoms (CDC, 2009a; Li et al., 2013). Differences in professional guidelines and medical insurance coverage related to who should receive what service at what frequency present a significant barrier to developing a systematic

approach to ensuring that those who need services receive them. Vision acuity screenings in community settings can identify school-aged children who have uncorrected refractive error, but the odds of receiving inadequate refractive correction remain significantly higher for Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic blacks than for whites, with the greatest disparities observed for the 12- to 19-year-old age group (Qiu et al., 2014). Although clinical care interventions and rehabilitation are available to improve or maintain the function of people living with vision impairment, knowledge about and access to these services is limited (Lam and Leat, 2015; Overbury and Wittich, 2011). Many public and private health insurance policies, including Medicare, do not cover periodic eye examinations for functionally asymptomatic or low-risk patients, corrective lenses, and visual assistive devices. In many cases, members of the public must purchase additional insurance or pay out of pocket for these services and items. These policies and circumstances contribute to inequities that already affect populations with lower socioeconomic status and poor health (DeVoe et al., 2007; Yip et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2013).

The committee noted that the relative success of clinical treatments, combined with the exclusion of eye and vision health from general health policy discussions and the resulting relative lack of shared expertise between public health professionals and eye care providers, has contributed to miscommunications and misconceptions about what represents a population health approach and how this approach relates to clinical care in eye and vision health. Even in its statement of work, the committee was asked to focus on mitigating the effects of vision impairment, a critical but downstream effect of vision loss that is not typically the focus of prevention efforts, which characteristically focus on more upstream determinants of health. As a result, it became important for the committee to develop a conceptual framework that illustrated the relationship between more traditional population health focuses and eye care.

Figure 1-3 presents a diagram of a cylinder, which can be used to conceptualize a comprehensive population health approach to improving eye and vision health and achieving health equity. The cylinder, which consists of the core public health functions, spans four sequential stages of prevention. Primordial prevention addresses broad health determinants and behaviors to minimize future health threats by targeting the environmental, economic, social, physical, and cultural factors that increase the risk of poor eye health. It may include such considerations as health literacy, housing, education, income, the availability of health care insurance, or policies to support healthy diets. Primary prevention seeks to support, educate, and promote healthy eye and vision behaviors that decrease the risk of poor eye and vision health. Examples in vision impairment include

SOURCE: Adapted from CDC, 2014.

using protective eyewear, spending adequate time outdoors, preventing and managing chronic conditions that predispose populations to vision loss, and ensuring adequate levels of light indoors for near-work activity. Secondary prevention facilitates the pre-symptomatic identification of eye diseases and treatments in order to slow or stop the progression of a disease or condition. Examples include screenings for children to detect and treat amblyopia and its risk factors and having a comprehensive eye examination to detect subclinical changes in the eye for glaucoma or diabetic retinopathy. Tertiary prevention includes activities designed to preserve and enhance the health, function, and quality of life of individuals with vision impairment. Examples include wearing properly corrected eyewear, improving medication adherence for glaucoma, and providing access to rehabilitation services, social support, or assistive devices. In this framework, vision impairment itself, regardless of the disease(s) or injury that caused it, is treated as a chronic condition in its own right.

Anchoring eye and vision health promotion in terms of the stages of prevention allows the nation to reevaluate eye and vision health improvement as not only a valued outcome in and of itself, but also as a potential public health tool with which to promote health equity more broadly among populations. Moreover, because the three public health functions and 10 essential health services address each prevention stage, this conceptual framework inherently creates a checklist from which to populate and evaluate a comprehensive public health approach to eye and vision health. That is, within each prevention stage, there will be actions related to assessment, assurance, and policy development that various stakeholders can pursue as part of a larger effort. This effort will take coordination and collaboration. A key role for governmental public health departments will be to serve as a convener of these stakeholders to develop and implement action plans that best reflect a community’s needs and goals.

This framework was also useful in structuring this report. In addition to introducing the committee’s statement of task, this chapter provides the committee’s guiding principles, defines key terms related to vision health, and proposes a new conceptual model to guide thinking about vision health as a population health priority. Chapter 2 describes the epidemiology of vision loss in the United States. Chapter 3 discusses the impact of vision loss and how that applies to current public health priorities. Chapter 4 explores the strengths and weaknesses of surveillance tools and systems and research databases to track and measure that burden. Chapter 5 examines the impact that individual health behaviors and community environments can have on the eye health and overall health of populations and reviews strategies to encourage collaboration and action at the community level. Chapter 6

examines the access to clinical services in terms of the distribution of the eye and vision workforce, and the coverage of health care services. Chapter 7 describes efforts to improve the quality and efficiency of clinical care. Chapter 8 focuses on efforts to improve the health and independence of individuals with chronic vision impairments and blindness. Finally, Chapter 9 proposes a model for action and recommendations for improving vision eye and vision health.

CONCLUSION

Vision impairment significantly affects the health, finances, and productivity of individuals, families, and society as a whole. Despite evidence that vision impairment increases the risk of mortality and morbidity from other chronic conditions and related injuries and is associated with a reduced quality of life, eye and vision health are not adequately recognized as a population health priority or as a means by which to achieve better health equity. This report attempts to answer “Why not?” by ascertaining what is known about the burden and epidemiology of vision loss, its risk factors, effective treatments and interventions to maintain or improve function, and population health strategies to introduce and sustain the prioritization of eye and vision health across communities. The report also serves as a call to action to make eye and vision health governmental public health and population health priorities.

A population health approach to eye and vision health must take into account the programs, policies, and systems needed to create the conditions where people can have the fullest capacity to see and that enable them to achieve their full potential. The long-term goal of a population health approach in eye and vision health is to transform vision impairment from an exceedingly common to a rare condition, reducing related health inequities. Given the genetic and biological components of many eye diseases and conditions, the occurrence of eye injuries, and the aging process itself, populations will never be without vision impairment. Nevertheless, this goal establishes a new platform from which to identify important players, define influential behaviors, and allocate resources in a manner that sustains and protects the eye and vision health of different populations. Anchoring population health in terms of prevention more broadly also creates an opportunity for the nation to reevaluate how it values eye and vision health and how this can be translated into daily activities, community discussions, and public policy.

Achieving the twin goals of improving eye and vision health and increasing health equity will require action by a wide range of stakeholders at the

national, state, and local levels. This chapter proposed guiding principles and a conceptual framework to guide and coordinate these actions. An effective population health approach to eye and vision health must address each of three public health functions (i.e., assessment, policy development, and assurance) across the four stages of prevention, which focus on sequential but narrowing opportunities for intervention across the continuum of eye and vision health. Prevention and early access to effective eye care is critical to avoiding, identifying, monitoring, and treating many eye diseases and conditions that can lead to vision impairment across the lifespan. Short- and long-term population health strategies should also account for the broad determinants of health, including policies that influence individual behaviors, safe and healthy environments and conditions, and their potential impact on eye and vision health. Good eye and vision health can reduce health disparities, but promoting optimal conditions for eye and vision health can alleviate many other social ailments, including poverty, other health inequities, increasing health care costs, and avoidable mortality and morbidity. The evidence provided throughout this report provides important context for the committee’s recommendations, which logically flow from the chapter conclusions. Establishing conditions and policies that promote population eye and vision health and minimize preventable and correctible vision impairment is an essential, timely, and achievable objective—an objective that is necessary to fuel broad actions and sustain the overall quality of life, function, and productivity of the nation.

REFERENCES

AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). 2004. Vision rehabilitation for elderly individuals with low vision or blindness. Rockville, MD: AHRQ. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coverage/DeterminationProcess/Downloads/id95TA.pdf (accessed March 29, 2016).

Alberti, C. F., E. Peli, and A. R. Bowers. 2014. Driving with hemianopia: III. Detection of stationary and approaching pedestrians in a simulator. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 55(1):368–374.

AOA (American Optometric Association). 2007. Care of the patient with visual impairment (low vision rehabilitation). St. Louis, MO: AOA. http://www.aoa.org/documents/optometrists/CPG-14.pdf (accessed June 1, 2016).

Bastable, S. B. 2016. Essentials of patient education. 2nd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett.

Birch, E. E. 2013. Amblyopia and binocular vision. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 33:67–84.

BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics). 2012. Injuries, illnesses, and fatalities. http://www.bls.gov/iif (accessed June 1, 2016).

Bowers, A. R., A. J. Mandel, R. B. Goldstein, and E. Peli. 2009. Driving with hemianopia, I: Detection performance in a driving simulator. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 50(11):5137–5147.

Braveman, P., and L. Gottlieb. 2014. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports 129(Suppl 2):19–31.

Bronstad, P. M., A. R. Bowers, A. Albu, R. Goldstein, and E. Peli. 2013. Driving with central field loss I: Effect of central scotomas on responses to hazards. JAMA Ophthalmology 131(3):303–309.

Brown, J. C., J. E. Goldstein, T. L. Chan, R. Massof, P. Ramulu, and the Low Vision Research Network Study Group. 2014. Characterizing functional complaints in patients seeking outpatient low-vision services in the United States. Ophthalmology 121(8):1655–1662, e1651.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2007. Improving the nation’s vision health: A coordinated public health approach. Atlanta, GA: CDC.

———. 2009a. Vision Health Initiative—Eye health tips. http://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/basic_information/eye_health_tips.htm (accessed October 7, 2015).

———. 2009b. Why is vision loss a public health problem? http://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/basic_information/vision_loss.htm (accessed October 7, 2015).

———. 2014. The public health system and the 10 essential public health services. http://www.cdc.gov/nphpsp/essentialservices.html (accessed March, 2016).

———. 2015a. About us. http://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/about/index.htm (accessed March 30, 2016).

———. 2015b. Conjunctivitis (pink eye) in newborns. http://www.cdc.gov/conjunctivitis/newborns.html (accessed March 30, 2016).

———. 2015c. Epidemiology and prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. 13th ed. Edited by J. Hamborsky, A. Kroger, and C. Wolfe. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation.

———. 2015d. National data. http://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/data/national.htm (accessed May 26, 2016).

———. 2015e. The work-related injury statistics query system. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/wisards/workrisqs (accessed August 5, 2016).

Christ, S. L., D. D. Zheng, B. K. Swenor, B. L. Lam, S. K. West, S. L. Tannenbaum, B. E. Muñoz, and D. J. Lee. 2014. Longitudinal relationships among visual acuity, daily functional status, and mortality: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. JAMA Ophthalmology 132(12):1400–1406.

Congdon, N., B. O’Colmain, C. C. Klaver, R. Klein, B. Munoz, D. S. Friedman, J. Kempen, H. R. Taylor, and P. Mitchell. 2004. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Archives of Ophthalmology 122(4):477–485.

Court, H., G. McLean, B. Guthrie, S. W. Mercer, and D. J. Smith. 2014. Visual impairment is associated with physical and mental comorbidities in older adults: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medicine 12:181.

Crewe, J. M., N. Morlet, W. H. Morgan, K. Spilsbury, A. S. Mukhtar, A. Clark, and J. B. Semmens. 2013. Mortality and hospital morbidity of working-age blind. British Journal of Ophthalmology 97(12):1579–1585.

Crews, J. E., G. C. Jones, and J. H. Kim. 2006. Double jeopardy: The effects of comorbid conditions among older people with vision loss. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness 100:824–848.

Crews, J. E., C.-F. Chiu-Fung Chou, J. A. Stevens, and J. B. Saadine. 2016a. Falls among persons aged > 65 years with and without severe vision impairment—United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 65(17):433–437.

Crews, J. E., C. F. Chou, M. M. Zack, X. Zhang, K. M. Bullard, A. R. Morse, and J. B. Saaddine. 2016b. The association of health-related quality of life with severity of visual impairment among people aged 40–64 years: Findings from the 2006–2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Ophthalmic Epidemiology 23(3):145–153.

Cumberland, P. M., J. S. Rahi, for the UK Biobank Eye and Vision Consortium. 2016. Visual function, social position, and health and life changes: The UK Biobank Study. JAMA Ophthalmology 134(9):959–966.

Dandona, L., and R. Dandona. 2006. Revision of visual impairment definitions in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases. BMC Medicine 4:7.

Dang, S. 2015. Eye injuries at work. http://www.aao.org/eye-health/tips-prevention/injuries-work (accessed February 16, 2016).

Davidson, S., and G. E. Quinn. 2011. The impact of pediatric vision disorders in adulthood. Pediatrics 127(2):334–339.

DeVoe, J. E., A. Baez, H. Angier, L. Krois, C. Edlund, and P. A. Carney. 2007. Insurance + access ≠ health care: Typology of barriers to health care access for low-income families. Annals of Family Medicine 5(6):511–518.

Frohman, E. M., J. G. Fujimoto, T. C. Frohman, P. A. Calabresi, G. Cutter, and L. J. Balcer. 2008. Optical coherence tomography: A window into the mechanisms of multiple sclerosis. Nature Clinical Practice Neurology 4(12):664–675.

Gostin, L. O. 2007. A theory and definition of public health law. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Law Center.

HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2015. Healthy people 2020 topics and objectives: Vision. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/vision (accessed October 7, 2015).

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 1988. The future of public health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

———. 2003. The future of the public’s health in the 21st century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

———. 2011. For the public’s health: The role of measurement in action and accountability. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Joseph, M.-A. M., and M. Robinson. 2012. Vocational experiences of college-educated individuals with visual impairments. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling 43(4):21.

Kirtland, K. A., J. B. Saaddine, L. S. Geiss, T. J. Thompson, M. F. Cotch, and P. P. Lee. 2015. Geographic disparity of severe vision loss—United States, 2009–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64(19):513–517.

Köberlein, J., K. Beifus, C. Schaffert, and R. P. Finger. 2013. The economic burden of visual impairment and blindness: A systematic review. BMJ Open 3(11):e003471.

Kulmala, J., P. Era, O. Pärssinen, R. Sakari, S. Sipilä, T. Rantanen, and E. Heikkinen. 2008. Lowered vision as a risk factor for injurious accidents in older people. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 20(1):25–30.

Kulmala, J., S. Sipilä, K. Tiainen, O. Pärssinen, M. Koskenvuo, J. Kaprio, and T. Rantanen. 2012. Vision in relation to lower extremity deficit in older women: Cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 24(5):461–467.

Kumaresan, J. 2005. Can blinding trachoma be eliminated by 20/20? Eye 19(10):1067–1073.

Lam, N., and S. J. Leat. 2015. Reprint of: Barriers to accessing low-vision care: The patient’s perspective. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology/Journal Canadien d’Ophtalmologie 50:S34–S39.

Lee, D. J., O. Gómez-Marín, B. L. Lam, and D. D. Zheng. 2002. Visual acuity impairment and mortality in U.S. adults. Archives of Ophthalmology 120(11):1544–1550.

———. 2003. Visual impairment and unintentional injury mortality: The National Health Interview Survey 1986–1994. American Journal of Ophthalmology 136(6):1152–1154.

Li, L.-H., A. Li, J.-Y. Zhao, G.-M. Zhang, J.-B. Mao, and P. J. Rychwalski. 2013. Finding of perinatal ocular examination performed on 3573, healthy full-term newborns. British Journal of Ophthalmology 97(5):588–591.

Lord, S. R. 2006. Visual risk factors for falls in older people. Age and Ageing 35(Suppl 2): ii42–ii45.

McGinnis, J. M., P. Williams-Russo, and J. R. Knickman. 2002. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Affairs (Millwood) 21(2):78–93.

NEI/NIH (National Eye Institute/National Institutes of Health). 2004. Vision statement and mission—National Plan For Eye and Vision Research [NEI strategic planning]. https://nei.nih.gov/strategicplanning/np_vision (accessed February 4, 2016).

———. 2008. Low vision. http://www.nei.nih.gov/health/lowvision (accessed February 16, 2016).

NLM (U.S. National Library of Medicine). 2016. Visual acuity test. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003396.htm (accessed August 5, 2016).

Overbury, O., and W. Wittich. 2011. Barriers to low vision rehabilitation: The Montreal Barriers Study. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 52(12):8933–8938.

Petrash, J. M. 2013. Aging and age-related diseases of the ocular lens and vitreous body. Investigative Ophthalmology and VisualScience 54(14):ORSF54–ORSF59.

Prasad, S. 2013. Visual problems due to pituitary tumors. http://www.brighamandwomens.org/Departments_and_Services/neurology/services/NeuroOphthamology/PituitaryTumor.aspx (accessed April 1, 2016).

Prevent Blindness. 2012a. Vision problems in the U.S. http://www.visionproblemsus.org (accessed February 12, 2016).

———. 2012b. Vision problems in the U.S.: Methods and sources. http://www.visionproblemsus.org/introduction/methods-and-sources.html (accessed July 5, 2016).

———. 2012c. Vision problems in the U.S.: Refractive error. http://www.visionproblemsus.org/refractive-error.html (accessed February 12, 2016).

Qiu, M., S. Y. Wang, K. Singh, and S. C. Lin. 2014. Racial disparities in uncorrected and undercorrected refractive error in the United States. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 55(10):6996–7005.

Rahi, J. S., P. M. Cumberland, and C. S. Peckham. 2009. Visual function in working-age adults: Early life influences and associations with health and social outcomes. Ophthalmology 116(10):1866–1871.

Rao, G. 2015. The Barrie Jones Lecture—Eye care for the neglected population: Challenges and solutions. Eye 29(1):30–45.

Rees, G., H. W. Tee, M. Marella, E. Fenwick, M. Dirani, and E. L. Lamoureux. 2010. Vision-specific distress and depressive symptoms in people with vision impairment. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 51(6):2891–2896.

Rein, D. B. 2013. Vision problems are a leading source of modifiable health expenditures. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 54(14):ORSF18–ORSF22.

Sengupta, S., S. W. van Landingham, S. D. Solomon, D. V. Do, D. S. Friedman, and P. Y. Ramulu. 2014. Driving habits in older patients with central vision loss. Ophthalmology 121(3):727–732.

Shahbazi, S., J. Studnicki, and C. W. Warner-Hillard. 2015. A cross-sectional retrospective analysis of the racial and geographic variations in cataract surgery. PLoS ONE 10(11):e0142459.

Sommer, A., J. M. Tielsch, J. Katz, H. A. Quigley, J. D. Gottsch, J. C. Javitt, J. F. Martone, R. M. Royall, K. A. Witt, and S. Ezrine. 1991. Racial differences in the cause-specific prevalence of blindness in East Baltimore. New England Journal of Medicine 325(20):1412–1417.

Ulldemolins, A. R., V. C. Lansingh, L. Guisasola Valencia, M. J. Carter, and K. A. Eckert. 2012. Social inequalities in blindness and visual impairment: A review of social determinants. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 60(5):368–375.

USPSTF (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force). 2009. Final recommendation statement—impaired visual acuity in older adults: Screening. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/impaired-visual-acuity-in-olderadults-screening (accessed October 7, 2015).

van Landingham, S. W., R. W. Massof, E. Chan, D. S. Friedman, and P. Y. Ramulu. 2014. Fear of falling in age-related macular degeneration. BMC Ophthalmology 14:1–10.

Varkey, J. B., J. G. Shantha, I. Crozier, C. S. Kraft, G. M. Lyon, A. K. Mehta, G. Kumar, J. R. Smith, M. H. Kainulainen, S. Whitmer, U. Ströher, T. M. Uyeki, B. S. Ribner, and S. Yeh. 2015. Persistence of Ebola virus in ocular fluid during convalescence. New England Journal of Medicine 372(25):2423–2427.

Varma, R., T. S. Vajaranant, B. Burkemper, S. Wu, M. Torres, C. Hsu, F. Choudhury, R. McKean-Cowdin. 2016. Visual impairment and blindness in adults in the United States: Demographic and geographic variations from 2015 to 2050. JAMA Ophthalmology 134(7):802–809.

Walter, C., R. Althouse, H. Humble, M. Leys, and J. Odom. 2004. West Virginia survey of visual health: Low vision and barriers to access. Visual Impairment Research 6(1):53–71.

Whitson, H. E., S. W. Cousins, B. M. Burchett, C. F. Hybels, C. F. Pieper, and H. J. Cohen. 2007. The combined effect of visual impairment and cognitive impairment on disability in older people. Journal of the American Geriatric Society 55(6):885–891.

Whitson, H. E., R. Malhotra, A. Chan, D. B. Matchar, and T. Ostbye. 2014. Comorbid visual and cognitive impairment: Relationship with disability status and self-rated health among older Singaporeans. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 26(3):310–319.

WHO (World Health Organization). 1986. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en (accessed October 7, 2015).

———. 2015. Blindness: Vision 2020—the global initiative for the elimination of avoidable blindness. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs213/en (accessed October 7, 2015).

———. n.d. Change the definition of blindness. http://www.who.int/blindness/Change%20the%20Definition%20of%20Blindness.pdf (accessed May 18, 2016).

Wittenborn, J., and D. Rein. 2013. Cost of vision problems: The economic burden of vision loss and eye disorders in the United States. Chicago, IL: NORC at the University of Chicago.

———. 2016. The potential costs and benefits of treatment for undiagnosed eye disorders. Paper prepared for the Committee on Public Health Approaches to Reduce Vision Impairment and Promote Eye Health. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2016/UndiagnosedEyeDisordersCommissionedPaper.pdf (accessed September 15, 2016).

Wittenborn, J., X. Zhang, C. W. Feagan, W. L. Crouse, S. Shrestha, A. R. Kemper, T. J. Hoerger, J. B. Saaddine, and the Vision Cost-Effectiveness Study Group. 2013. The economic burden of vision loss and eye disorders among the United States population younger than 40 years. Ophthalmology 120(9):1728–1735.

Wood, J. M., P. F. Lacherez, and K. J. Anstey. 2012. Not all older adults have insight into their driving abilities: Evidence from an on-road assessment and implications for policy. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 68(5):559–566.

Yip, J. L., R. Luben, A. P. Khawaja, D. C. Broadway, N. Wareham, K. T. Khaw, and P. J. Foster. 2014. Area deprivation, individual socioeconomic status and low vision in the Epic-Norfolk Eye Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 68(3):204–210.

Zambelli-Weiner, A., J. E. Crews, and D. S. Friedman. 2012. Disparities in adult vision health in the United States. American Journal of Ophthalmology 154(6 Suppl):S23–S30, e21.

Zhang, X., M. F. Cotch, A. Ryskulova, S. A. Primo, P. Nair, C. F. Chou, L. S. Geiss, L. E. Barker, A. F. Elliott, J. E. Crews, and J. B. Saaddine. 2012. Vision health disparities in the United States by race/ethnicity, education, and economic status: Findings from two nationally representative surveys. American Journal of Ophthalmology 154(6):53–62.

Zhang, X., G. L. Beckles, C. F. Chou, J. B. Saaddine, M. R. Wilson, P. P. Lee, N. Parvathy, A. Ryskulova, and L. S. Geiss. 2013. Socioeconomic disparity in use of eye care services among U.S. adults with age-related eye diseases: National Health Interview Survey, 2002 and 2008. JAMA Ophthalmology 131(9):1198–1206.