6

Key Lessons for Programs and Policies

Although, as discussed in the preceding chapter, significant challenges are entailed in developing and sustaining a skilled technical workforce, there is evidence for a variety of solutions that work by encouraging and facilitating collaborative partnerships across local employers; community colleges; high schools; universities; and local, state, and federal government agencies. These initiatives also can create the right incentives for employers and workers to remain engaged and vested in their local market for skilled technical work. This chapter reviews some leading programs and policies focused on achieving these ends.

Section 6.1 looks at how better to link students to skilled technical education and training opportunities and improve success rates, recognizing that students face substantial challenges in navigating, paying for, and completing such programs. Section 6.2 considers strategies for better linking secondary and postsecondary education and training, including early college schools, career academies, and dual-enrollment programs. Section 6.3 examines the links between postsecondary educational organizations and employers; the discussion encompasses strategic centers of excellence at community and technical colleges and sector-specific training programs. Section 6.4 looks at employer training programs, including the role of employers in developing apprenticeships, as well as efforts by labor unions to foster joint labor–management programs. Section 6.5 considers efforts to improve the collection, analysis, dissemination, and widespread use of data that can be used to improve the linkages discussed in the preceding section. Section 6.6 examines other policy initiatives aimed at improving career and technical education (CTE), including those focused on portable credentials and licenses, standardized credentials, licensing reforms, and competency models. Finally, Section 6.7 provides conclusions.

The polycentric nature of the skilled technical workforce development system in the United States provides the opportunity for many simultaneous policy and partnership experiments. This, in turn, makes it possible for civic

leaders to examine the needs of their communities, study the experiences of others, and develop initiatives that address the identified needs.1 Assessing these initiatives remains a challenge, however. While this report cites research pertaining to the variety of initiatives under way across the United States, the large size and complexity of the U.S. workforce development system makes it difficult to survey, evaluate, and monitor these initiatives comprehensively. The effectiveness of any particular strategy can depend not only on the validity of its concept and the rigor of its implementation but also on the presence of complementary linkages with other components of the system. Thus while this chapter highlights an array of noteworthy initiatives to develop and sustain a skilled technical workforce and presents evidence (where available) of their impacts, it is important to note that in many cases, research on these initiatives has not yet been conducted, and therefore their relative value and potential impacts have not yet been assessed.

6.1 LINKING STUDENTS TO SKILLED TECHNICAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES AND IMPROVING SUCCESS RATES

As discussed in Chapter 5, evidence shows high economic and social benefits of completing postsecondary education and training, but a number of factors inhibit students from either choosing or completing this course of preparation. This section reviews the evidence on the effectiveness of policy measures aimed at encouraging enrollment in skilled technical education and training and improving completion rates. These policy measures include those focused on improved counseling services, financing strategies, wraparound services, improved remediation, improved outcomes for adult learners, leveraging of online learning, and improved incentives for completion at the community college level.

Although this chapter focuses on public 2-year institutions (community colleges), many private for-profit institutions offer similar education and training programs (see Chapter 4). While for-profit institutions can help meet the demand for skilled technical education and training, the evidence suggests that completion rates, default rates, and labor market outcomes are worse for for-profit than for public 2-year institutions (Deming et al., 2013).

__________________

1 The National Center on Education and the Economy and the National Conference on State Legislatures have formed a study group to investigate top-performing education jurisdictions. For information, see NCEE (2017).

6.1.1 Improved Counseling Services

There appears to be widespread consensus among education experts that policy makers, educators, and employers need to do a better job of helping students and adult workers understand the link between education and training programs and employment. The Accelerated Study in Associate Programs (ASAP) at the City University of New York (CUNY), discussed further below, provides evidence that advising, career services, and tutoring play an important role in improving completion rates (Scrivener et al., 2015).2 Career guidance is particularly important for skilled technical workforce development to counter the common perception that the only path to lifelong occupational success is through immediate entry into a 4-year college and advanced degree programs (see Chapter 5).

Some analysts believe that without career counseling and reliable occupational information, students pay insufficient attention to labor market trends when choosing a field of study (Long et al., 2014). When industries and occupations are changing, it is particularly challenging for students and job seekers to identify viable career options and the associated education and training requirements. At the same time, data suggest that K-12 schools, postsecondary schools, and worker assistance agencies have reduced support for counselors and advisors because of budget pressures and changing priorities (Good and Strong, 2015). Inadequate occupational guidance potentially increases the costs of education and training, creates imbalances in labor markets, and reduces returns on investment in skilled technical workforce development.

Research suggests that One Stop Career Centers often provide the type of career advising that is lacking in many educational institutions, and a variety of collaborations can be encouraged, depending upon local requirements (Holzer, 2015b). Under new provisions in the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), states can rethink and expand the reach of these job centers to better serve a broad range of clients. For example, some states have purchased online job databases such as Help Wanted OnLine® to help their One Stop Career Centers better match job seekers with jobs. Nearly a quarter of One Stop Career Centers are now located on college campuses, and even more are deploying staff

__________________

2Scrivener and colleagues (2015) used randomized controlled trials to evaluate the impact of ASAP over a 3-year period compared with the usual services and courses provided at CUNY, finding that graduation rates within 3 years nearly doubled. Along with these student services, students were required to be full-time students and were provided additional financial support, such as tuition waiver, free use of textbooks, and cards for free public transportation. The ASAP program has student-advisor ratios between 60:1 and 80:1. A study of two colleges in northern Ohio found that enhanced academic counseling with an average of a 160:1 student-adviser ratio had only modest short-term effects (Scrivener and Coghlan, 2011).

to campuses on a part-time basis. States also can take steps to reform job center metrics to better reflect the quality of advising activities rather than the number of referrals.

In addition to improving completion rates, counseling and career services can increase enrollment in skilled technical education and training where the returns are higher. As discussed in Chapter 5, however, many parents, students, and workers perceive career preparation programs such as CTE to be associated with lower socioeconomic status and lower career ambitions (see, e.g., Herian, 2010). If the challenges of skilled technical workforce development are to be addressed effectively, this perception must be changed so that programs to provide job skills and training are no longer viewed as a substitute for college but as a robust way to contextualize academic learning.

The best education and training programs prepare students to enter the workforce and pursue lifelong learning by encouraging the development of general technical skills, occupational skills, and “soft skills” that make for reliable and collegial employees (Bronson, 2007). However, the current overemphasis on 4-year college-preparatory curricula may inhibit students from receiving the workplace training necessary to acquire soft skills and from learning enough technical content to become skilled workers (see Bolli and Hof, 2014; Bolli and Renold, 2015). Thus, students may need to receive counseling even before entering community college so that they realize the potential gains from pursuing this training.

Instead of offering a program solely designed to prepare students for 4-year college programs, then, another option is to prepare them by developing technical skills and then help them prepare for and choose among postsecondary education and training and career alternatives. This emphasis on a strong technical foundation can improve public perceptions of career preparation programs, enhance the employment prospects of graduates, and develop a better workforce.

6.1.2 Financing Strategies

As discussed in Chapter 5, the rising costs of community college and inadequate financial aid can be a barrier to completion for many low-income students. Some federal aid, such as Pell Grants, is limited to undergraduate students in for-credit programs and is not available for students taking continuing education classes, even when they are earning a certificate (Greenhouse, 2013). An evaluation of two colleges in New Orleans found that providing financial aid tied to academic benchmarks to supplement other financial aid increased the likelihood that students enrolled full-time and earned more credits (Scrivener and Coghlan, 2011). Although only a small fraction of students in the ASAP program received tuition waivers, it may be that the availability of such financial support increased full-time enrollment in CUNY colleges by reducing worry about future financial aid (Scrivener et al., 2015). In

addition to the direct costs of community college, students have to weigh foregone earnings when in school and the need to balance college and work for many parents.

Braiding Strategies

Some states are seeking to combine public resources to support postsecondary education and training programs using “braiding strategies,” which merge public dollars for a common purpose while keeping categorical funds distinct. For example, Oregon’s Career Pathways Statewide Initiative braids Perkins Act, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Workforce Investment Act (WIA), and state general funds to finance career pathways programs in the postsecondary education system. In Arkansas, the Career Pathways Initiative (CPI) has partnered with the local division of child care and early childhood education offices to connect students to state subsidies for child care (Hoffman and Reindl, 2011). In addition, CPI students are assigned a tutor and a counselor to help them address any issues and obtain other services.

Lifelong Learning

Some states also are experimenting with strategies for ensuring that U.S. workers and employers continue to invest in education and training throughout the career span. Maine, for example, is experimenting with portable, employee-owned Lifelong Learning Accounts (LILAs) that permit employees, employers, and the state to pool funds for continual worker education and training (Hoffman and Reindl, 2011). LILAs, which are managed by the Maine Finance Authority, can be used for postsecondary education and training courses as well as books and supplies. In addition, LILA holders have access to career counselors.3

6.1.3 Wraparound Services

Providing education, training, and opportunity often is insufficient to ensure success for many youth and adult learners, many of whom are unfamiliar with school processes and policies or need help meeting family, work, and financial responsibilities. “Wraparound” student support services at the postsecondary level, such as those described in Box 6-1, can be particularly beneficial for low-income and first-generation students, who may not have the resources or social networks to navigate the higher education system and to persist to complete their degree programs. A recent study of the ASAP program

__________________

3 For information about Maine’s LILAs, see www.bos.frb.org/commdev/c&b/index.htm (accessed March 21, 2017).

at CUNY, discussed earlier, suggests that focusing on wraparound services can improve returns on investment in skilled technical education and training. The program offers full-time students intensive advising and tutoring, priority in registering for oversubscribed courses, free transportation, free textbooks, and a waiver that covers any shortfall between schooling costs and financial aid. A randomized controlled trial of the program showed significant positive outcomes. The program nearly doubled the share of students graduating within 3 years, increased the share enrolling in a 4-year college, and provided a satisfactory return on investment. The program was estimated to have increased per-student costs by 60 percent, or about $5,400 a year. However, the near doubling of graduation rates means that CUNY actually spent more than 10 percent less per college degree (Dynarski, 2015).4

Wraparound services may be standard and comprehensive or operate on a piecemeal or smaller scale, depending on local requirements. An example of a small-scale program is Massachusetts Bunker Hill Community College’s (BHCC) emergency assistance fund.5 This fund provides small one-time grants

__________________

4 Some experts argue that wraparound services are important at the secondary as well as the postsecondary level. The committee believes this is an important issue; however, a detailed examination of secondary education is beyond the scope of this study.

5 For information about the fund, see http://www.bhcc.mass.edu/emergencyassistancefund (accessed March 21, 2017).

to students for emergencies that occur during the semester and may cause them to drop out of college, such as a lost or stolen laptop, a medical emergency, or a car accident. Students who document such a need may receive up to $1,000 to help them get back on their feet and stay in school. In fiscal year 2012, the fund assisted 147 students and disbursed more than $100,000; the average grant was about $700. BHCC reports that the retention rate for students receiving assistance through the fund is 31 percent higher than that for the entire student population.

6.1.4 Improved Remediation

As discussed in Chapter 5, students who need to take remedial courses relative to those who do not are more likely to drop out of a postsecondary program. Nearly two-thirds of students entering community college are asked to take either remedial English or math classes (NCES, 2016a). Students who need to take two or three remedial classes in a subject are unlikely ever to complete a college-level class in that subject (Bailey and Jaggars, 2016). In addition, there is some evidence that the remediation is not effective: one study found that the vast majority (72 percent) of students who ignored the referral to a remedial class ended up completing the college-level class, compared with only 27 percent of students who complied with the referral (Bailey et al., 2010).

Reducing the Need for Remediation

As discussed in Chapter 5, many students entering college are assigned to noncredit developmental courses that increase the costs and lengthen the time for obtaining a degree. Some analysts are questioning the way students’ readiness is assessed and whether the need for developmental coursework is as prevalent as some have assumed.6 Improving readiness assessments could be a low-cost, high-benefit intervention to increase college access for many students. For example, using high school transcript information—either instead of or in addition to test scores—could significantly reduce the prevalence of assignment errors (Scott-Clayton et al., 2012).

__________________

6 Many public colleges and universities use a computerized test, known as ACCUPLACER, to assess students’ skills in mathematics, writing, and reading. However, recent research has found that under current test-based policies, about one in four test takers in mathematics and one in three test takers in English are assigned improperly to developmental courses. In addition to inaccurate assessments, the value of the developmental coursework has been challenged. For example, many community colleges require students to pass Algebra I before taking for-credit classes even in fields in which this mathematics track is not required.

The following subsections review evidence that integrating remediation into skills training classes, as well as using accelerated remedial coursework, can improve completion rates. Methods of reducing the need for remedial classes, including improving elementary and secondary education and better integrating secondary and postsecondary education, are then discussed.

Integrating Remediation

Schools can do a better job of assessing student readiness for postsecondary education and training and of designing more appropriate and cost-effective prerequisite requirements. Moreover, several studies indicate that it is possible to integrate academic preparation for postsecondary education and training with technical training to motivate students and to hasten readiness for skilled technical occupations (see, e.g., Hoffman and Reindl, 2011; Howington et al., 2015; Wachen et al., 2012).

Readiness can be improved by integrating developmental content into courses that are offered for credit instead of delivering it as a stand-alone course (see Bettinger et al., 2013).7 The state of Washington’s Integrated Basic Education and Skills Training (I-BEST) program, for example, offers academic instruction in the context of technical education (Hoffman and Reindl, 2011). Adult literacy and career-technical instructors co-teach courses that provide students with developmental support while they earn credit toward a certificate or degree. A multiyear evaluation of I-BEST found that when developmental instruction was combined with for-credit classes, students developed basic skills more closely tied to their field of study, were more likely to persist in their coursework, and did not waste financial resources on noncredit coursework (Wachen et al., 2012, using outcomes of I-BEST students matched to those of students with similar characteristics). The evidence also indicates that I-BEST students earn nearly twice as many college credits as non-I-BEST students and are more likely to earn occupational certifications. Moreover, the program’s benefits and costs have been estimated to be approximately equal, suggesting that such programs can be designed so that no additional resources are needed to achieve better results (Wachen et al., 2012).

Several other states have launched integrated programs to help students develop more quickly the skills they need to obtain postsecondary credentials. The Minnesota Training, Resources and Credentialing for Pathways to Sustainable Employment program (FastTRAC), for example, uses a modular approach to attaining credentials that is modeled on the Washington I-BEST program (Hoffman and Reindl, 2011).

__________________

7 Some of the approaches discussed in this section also serve as examples of articulating career pathways, which is discussed in more detail in a later section of this chapter.

Similarly, the state of Illinois created a plan to help adults quickly obtain a postsecondary degree valued by employers through “bridge” programs in community colleges located across the state (Hoffman and Reindl, 2011). These programs help students bridge the gap between their secondary education and the academic skills needed to succeed in postsecondary training. Students enrolled in bridge programs simultaneously receive academic and occupational instruction, which provides important context for learning.

The Florida College and Career Readiness Initiative (FCCRI) is another statewide program that assesses the college readiness of high school juniors and for those assessed as not ready for college, provides them with instruction as high school seniors (Mokher et al., 2014). A similar bridge program launched by LaGuardia Community College targets high school dropouts. This adult education program provides a bridge to a General Educational Development (GED) credential and continued postsecondary training. An evaluation by researchers at MDRC showed that bridge students at LaGuardia Community College were more likely to have passed the GED exam and enrolled in college relative to students in traditional GED preparation courses (Martin and Broadus, 2013).

Accelerating Remediation

In addition to integrating remedial classes with skills training and linking it to the students’ fields of interest, providing accelerated remedial courses or co-requisite classes may reduce the incidence of students dropping out before completing required remedial courses. Acceleration strategies can include tailoring the curriculum to eliminate unnecessary topics, accelerating the pace of the remedial classes to reduce the number of dropout points, or linking college-level enrollment to a companion remedial class. Evidence from the Community College of Baltimore’s Accelerated Learning Program revealed that students taking co-requisite and sequential remedial classes had the same pass rates for the college-level classes, but that students taking the co-requisite classes were able to accrue college-level credits more quickly. And Tennessee’s co-requisite program showed a much higher rate of passing the college-level math and writing sequences (Bailey and Jaggars, 2016).

6.1.5 Improved Outcomes for Adult Learners

Community colleges serve adult learners in addition to students who enter immediately after graduating from high school. As discussed in Chapter 4, a significant portion of community college students are aged 30 and older. Career pathways, described below, focus on these adult learners. They entail linking two or more systems to improve education and training outcomes in a process known as “articulation” (King and Prince, 2015). There is some evidence that career pathway programs have significant impacts on employment and earnings

that tend to be longer-lasting than those of typical workforce programs, including higher wages and increased employment (Smith and King, 2011). While these results are not based on rigorous experimental evidence, randomized controlled trials of these programs are ongoing.

Career pathways are “roadmaps” of the education and training required to attain credentials associated with success in specific industries, often used to guide linked learning, sector strategies, talent management, and career pipeline initiatives. This approach has been adopted in several states.

Career pathways are typically targeted to meet the demands of local labor markets. The programs and resources of local community colleges, workforce development agencies, and social service providers are integrated to create structured sequences of education, training, and on-the-job learning in strategically important occupational areas (Alssid et al., 2002). Ideally, career pathways offer “a series of connected education and training programs and support services that enable individuals to secure employment within a specific industry or occupational sector, and to advance over time to successively higher levels of education and employment in that sector” (Jenkins and Spence, 2006, p. 2). They also often involve bridge programs to address the skill deficiencies of participants and the challenge of moving them along an accelerated pathway.

Several states, including Arkansas, Montana, Oregon, Virginia, and Washington, have developed statewide career pathways initiatives that are relevant for secondary and postsecondary education (Hoffman and Reindl, 2011). One often-cited example is that of Shifting Gears, launched in 2007 with the support of the Joyce Foundation and matching funds in six states (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin). This initiative prioritized industry and occupational sectors that offer skilled technical jobs; broke down longer diploma and degree requirements into shorter certificate models; and offered classes at a wider variety of places, days, and times (Strawn, 2010). In Minnesota, the Shifting Gears program evolved into the FastTRAC Adult Career Pathway partnership, which combined multiple federal, state, and philanthropic funds to serve 3,385 individuals between 2009 and 2012.8

Similar programs, created through the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP)-led Alliance for Quality Career Pathways (AQCP) Framework 1.0, focus on connecting adult learners with needed remediation and then getting them into training programs. To develop AQCP Framework 1.0, CLASP worked jointly with 10 states—Arkansas, California, Illinois, Kentucky, Massachusetts,

__________________

8 Self-reported data indicate that 88 percent of these individuals completed industry-recognized credentials and/or credits. Among those exiting the program, 57 percent entered employment, and of those, 84.8 percent retained employment for at least 6 months. Among those with wages over the entire year, exiters earned on average $21,080 annually, a 33 percent increase over their annual earnings in the year prior to enrollment (Choitz et al., 2015).

Minnesota, Oregon, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin—thereby establishing a common understanding of quality career pathways and systems.9 The framework provides criteria, indicators, and metrics for use in evaluating and creating state and local career pathways (CLASP, 2014).

6.1.6 Leveraging of Online Learning

Technology developments that support online learning make it possible for educators to create flexible learning environments that accelerate education and training, as well as facilitate the development of knowledge and practice communities that can be sustained over time using social media.

Distance education goes back decades, and many postsecondary programs are now delivering courses online. The Center for Adult Learning in Louisiana (CALL), for example, offers 13 online programs in accelerated formats for adult learners. Operated jointly by the Louisiana Board of Regents and the Southern Regional Education Board, CALL specifically targets adults and is provided exclusively online to accommodate the schedules of working students. Courses are taught in 4- and 8-week formats. Time to degree completion is accelerated through prior learning assessments, which offer students college credit for work, volunteer, or life experiences (Hoffman and Reindl, 2011). All CALL students are eligible for financial aid and are provided a range of support services. Similarly, a pilot training program funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) trained Navy recruits and unemployed veterans with no previous technical experience to perform at or above the competency level of a 10-year information technology (IT) expert with only 16 weeks of intensive online training (The White House, 2014). Still another example is a cross-state experiment in creating a virtual university that enrolls students from 50 states in the Western Governors University (WGU), a nonprofit online university (The White House, 2014). WGU, which costs approximately $6,000 per year and is nationally and regionally accredited, offers a competency-based curriculum that enables progress toward a degree based on demonstrated skills rather than number of credit hours.10

The rise of online education, particularly the recent growth of massive open online courses (MOOCs), makes it possible to increase the scale, interactivity, sophistication, and personalization of distance learning, as well as to enhance the learning experience. For example, Coursera and edX, two

__________________

9 For information on the CLASP initiative, see CLASP (2014).

10 Competency-based learning, which focuses on helping students master content, awarding credit, and permitting progress based on competency, can be considered a strategy for K-16 reform. For a definition of competency-based learning and an overview of issues and contemporary debates, see the entry on competency-based learning in The Glossary of Education Reform (Great Schools Partnership, 2014).

popular MOOC platforms, have more than 15 million enrollees from nearly 200 countries (Willcox et al., 2016). However, education research historically has focused on learning in the classroom and is only just beginning to consider the role and impact of online learning. A recent study by researchers affiliated with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Online Education Policy Initiative argues that if the proliferation of online learning is properly understood and leveraged, it can serve as a catalyst for reform in postsecondary education and training, although it cannot and should not replace teachers (Willcox et al., 2016) (see Box 6-2).

6.1.7 Improved Incentives for Completion at the Community College Level

Some states are already strengthening incentives for community colleges to respond to the skills needed in the labor market and to improve completion

rates. Community colleges traditionally have received state-level funding based on the number of enrolled students. As of July 2015, however, 32 states had implemented funding formulas that allocate a portion of a college’s funding based on such indicators as course completion, time to degree, transfer rates, the number of degrees awarded, and the number of low-income and minority graduates (NCSL, 2015). Yet it may be that reliance on these academic performance-based funding requirements will lead to more selective admissions criteria (Kelchen and Stedrak, 2016) or lowered standards for completion (Courty and Marschke, 2011). State policy makers thus might do better to attempt to create better incentives for improved completion rates by linking funding to employment metrics, such as earnings of students after graduation, or to metrics focused on increasing enrollment and completion for students who obtain credentials that are in high demand among employers or offer higher returns on investment (Holzer, 2015a).

6.2 LINKING SECONDARY AND POSTSECONDARY EDUCATION AND TRAINING

Better integration of academic and technical education and training can improve the quality of postsecondary education and training and increase the return on investment in education and training for skilled technical occupations (DOL et al., 2014). As discussed in Chapter 5, inadequate preparation in primary and secondary school may be a large part of the reason that students fail to complete their education. Strategies for reforming postsecondary education and training include creating flexible and integrated learning environments, particularly in community colleges and technical schools, and reassessing the readiness of students for postsecondary education and training and prerequisite requirements and programs.

In his paper commissioned for this study, Stern (2015) suggests that a better approach to secondary education is to prepare all high school students for both employment and a full range of postsecondary education and training options, and to avoid making assumptions about future education and training attainment or segregating students on this basis.11 In his opinion, the coursework required for 4-year college admission can and should be available to all students willing to put in the effort. He argues that high school students should master a sequence of academic and CTE coursework that will help them earn a living

__________________

11 This is not a new proposal. The School-to-Work Opportunities Act of 1994 (STWOA) embraced a similar philosophy and provided funds for activities classified as work-based learning, school-based learning, or connecting activities. For reviews of the challenges associated with implementing STWOA, see, for example, Hollenbeck (1997) and Neumark (2004).

regardless of whether they pursue or complete a 4-year college degree. He outlines several design principles to “make [secondary education] real and make it fair” (see Box 6-3).

Stern’s findings also are relevant for state and federal policy makers. Citing a 2013 study by the National Association of State Directors of Career Technical Education Consortium and the Independent Advisory Panel for the 2014 National Assessment of Career and Technical Education, Stern calls for changing CTE standards (which now tend to be course-specific and geared toward preparing students for particular jobs) so they are aligned with a set of broader career clusters and pathways. He also makes the case that the pending reauthorization of the Perkins Act provides an opportunity for federal policy makers to eliminate bureaucratic rules that effectively maintain CTE as a silo of isolated activities and to better integrate CTE across several education reform efforts. In addition, a variety of programs, discussed in the next section, link secondary and postsecondary education and training with particular employers.

Clear linkages between secondary and postsecondary institutions can help students transition from secondary to postsecondary education and later, from education to employment. These linkages can improve student preparedness, reduce the costs of education and training, help students learn about college programs and processes, build critical social networks and supports, and improve returns on investments (Karp, 2015b). Programs designed to improve these linkages include early college schools, career academies, and dual- or concurrent-enrollment programs, discussed below.

6.2.1 Early College Schools

Early college schools integrate high school and college education and training in a rigorous yet supportive environment.12 Each such school requires a collaborative partnership between a school district and a 2- or 4-year postsecondary school. One example is the P-Tech model, described in Box 6-4.

Most early college schools enroll a higher percentage of minority students relative to their corresponding school district and state, with an average of 60 percent of students coming from low-income families. Over the past decade, early college schools have produced significant outcomes for low-income youth, first-generation college students, and minority students. Based on a study of 100 representative early college high schools, for example, about 90 percent of early college students graduated high school, a figure 12 percentage points higher than the national average of 78 percent. Of the 2,600 early college

__________________

12 The committee’s definition of early college programs embraces both 2- and 4-year postsecondary educational programs, which include “middle college” programs.

graduates who enrolled in postsecondary education and training, only 14 percent enrolled in coursework to prepare them for college-level work, compared with 23 percent nationwide. In addition, the majority of early college students earned college credit in high school, and 30 percent earned an associate’s degree with their diploma. Early college school graduates thus were able to start their careers without college debt or with less debt than is typical (Webb and Gerwin, 2014).

The states of Michigan and New York have been at the forefront of the early college movement; however, a variety of programmatic models for early college schools have emerged.13 With the help of more than $130 million in private start-up funds, the number of early college schools has grown from 3 in 2002 to 280 in 2014, serving more than 80,000 students and producing more than 5,000 graduates. Start-up costs range from $125,000 to establish an early college program within an existing high school, to $500,000 to establish a program on a college campus, to more than $3.5 million to establish a separate stand-alone early college charter school. Early college schools receive anywhere from $90,000 to $400,000 in grants from the coalition of funders that sponsors the national Early College High School Initiative. For programs established within existing high schools, these grants cover about 70 to 80 percent of start-up costs. Public school districts provide the ongoing operating budget for each early college school as they do for traditional high schools.

The Pathways to Prosperity program is another example of an initiative that links high school CTE with postsecondary education and training. In 2012, the Harvard Graduate School of Education and Jobs for the Future created the Pathways to Prosperity Network to help state, regional, and local educators, employers, and intermediary organizations build and scale up career pathways initiatives that span grades 9-14. The network’s 2014 report indicates that at that time, the network included 10 states: Arizona, California, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, Missouri, New York, Ohio, and Tennessee (Jobs for the Future, 2014).

6.2.2 Career Academies

Career academies are small learning communities within schools that provide a college-preparatory curriculum with a career-related theme.14 In some

__________________

13 Examples of other models include middle college programs such as the Secondary Technical Education Program (STEP) in the Anoka-Hennepin School District in Minnesota and Washtenaw Technical Middle College (WTMC) in Washtenaw, Michigan. For information on the STEP program, see http://www.anoka.k12.mn.us/domain/2247 (accessed March 22, 2017). For information on WTMC, see http://www.themiddlecollege.org (accessed March 22, 2017). For an overview of early college models and student experience, see Barnett et al. (2015).

14 See, for example, Kemple (2008) and Castellano et al. (2012). Some analysts argue that evidence of the benefits of career academies may be overstated because of bias

cases, these academies can generate large improvements in earnings for students for many years beyond graduation. In addition, many of these academies have demonstrated the ability to maintain mathematics and science instruction at high levels (Castellano et al., 2012).

Initiated in 1969 in Philadelphia with the Electric Academy at Edison High School, career academies in the United States now number more than 7,000 and cover a wide range of career areas (see, e.g., Stern et al., 2010).15 One model is the National Academy Foundation (NAF), described in Box 6-5, which partners with educators at existing high schools, businesses, and civic leaders in high-need communities across the United States (see Orr et al., 2004, for a review of NAF’s work). Other models for career academies include the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB) High Schools That Work; High Tech High; and regional technical centers in such states as Ohio, Massachusetts, and Washington.16

6.2.3 Dual- or Concurrent-Enrollment Programs

Dual- or concurrent-enrollment programs, also known as dual-credit technical programs, provide opportunities for high school students to take college-level courses free of charge and simultaneously earn credit toward high school completion and a college degree. Emerging from local practice in the 1980s, these programs have evolved without guidelines, regulation, or a policy framework, which has resulted in wide variation in state practices.17 Recent years have seen a movement to learn from, accredit, and provide practice guidelines for these programs. As of the 2015-2016 school year, there were 97 accredited concurrent-enrollment programs nationwide: 59 at 2-year public colleges, 29 at 4-year public universities, and 9 at 4-year private colleges and universities (Scheffel, 2016).

One advantage of dual- or concurrent-enrollment programs is that they respond to local and state education and training needs (Scheffel, 2016). For example, if community leaders and elected officials in a specific location launch

__________________

introduced by self-selection, which is difficult to control for in research studies. For example, effects may be stronger for boys than for girls and for those in certain types of programs, such as information and communication technologies.

15 For additional background and resources, see Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy (n.d.).

16 For more information, see SREB High Schools That Work, http://www.sreb.org/abouthstw and High Tech High, http://www.hightechhigh.org/about.

17 For a report that explores how states regulate and ensure the quality of dual-credit programs, see Taylor et al. (2015). The authors indicate that programs in Minnesota are an exception: the state was an early adopter of dual-credit programs in the 1980s and provided educators with a policy framework to guide their efforts.

an economic development initiative related to a particular industry, concurrent-enrollment courses can be designed and offered to help students learn technical skills and prepare them for a certificate or degree program that will meet the demands of local employers. Concurrent-enrollment courses also can be adapted to new programs and fields at the 4-year college level.

Of course, this localized approach also brings variation in quality. Even so, the evidence to date suggests that concurrent-enrollment programs have positive impacts for both students and society (Krueger, 2006). In her paper commissioned for this study, Karp (2015b) points out that when properly leveraged, these programs can help the United States achieve its postsecondary education goals by strategically linking high schools and colleges, stimulating educators to rethink how education is structured and delivered, and forcing operational change at the organizational level.

6.3 LINKING TRAINING AND WORK

Many employers are seeking to partner more closely with community or technical colleges. Similarly, many educators are seeking to partner with employers to develop more relevant education and training programs. These educational institution–employer partnerships have the potential to create better-integrated learning environments and meet local employers’ skill requirements. The idea is that employers will provide input on courses and curricula and will contribute to ensuring that students acquire skills that will lead directly to a job upon graduation.

Flexible and integrated learning environments for skilled technical occupations involve the alignment of community and technical college education and training with economic development objectives and opportunities, as well as the creation of modular, short-term programs that can be stacked over time; delivered in a variety of ways; and integrated with skills, academic, and occupational certification programs (see Box 6-6). Effecting these types of changes requires that community and technical colleges build effective partnerships with employers, industry and trade associations, and labor unions.

These partnerships are modestly supported by the federal government. For example, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Trade Adjustment Assistance Community College and Career Training (TAACCCT) grant program provides 256 grants totaling $1.9 billion over 4 years, authorized under the 2010 Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act. TAACCCT helps community colleges and other eligible institutions of higher education expand and improve their education and career training programs. The Department of Labor implements the TAACCCT program in partnership with the U.S. Department of Education.18

There is evidence that certain of these programs raise earnings for at-risk students, often in technical fields, when they integrate classroom training with workplace experience in a particular sector or employer. Examples of these programs include strategic centers of excellence at community and technical colleges and sector-specific training programs involving partnerships between training providers, often community colleges, and employers and trade associations in a single industry.

__________________

18 For an overview of the evidence on federally funded education and training programs, see DOL et al. (2014).

6.3.1 Strategic Centers of Excellence at Community and Technical Colleges

Centers of excellence at community and technical colleges are designed to foster flexible and integrative learning in strategically important local industries. In 2004-2005, for example, the Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges created 10 centers of excellence to serve as integrators and catalysts for economic and workforce development in the state’s leading industries.19 The centers were placed on college campuses through a competitive application process and codified into state statute in 2008 (WA HB1323). They are intended to serve as a point of contact and resource hub for industry trends, best practices, innovative curriculum, and professional development. (See Box 6-7 for details on one of the centers.) Core foci of these centers include the following:

- Economic Development Focus. Serve as partners with various state and local agencies and regional, national, and global organizations to support economic vitality and competitiveness in Washington’s driver industries.

- Industry-Sector Strategy Focus. Collaboratively build, expand, and leverage industry, labor, and community and technical college partnerships to support and promote responsive, rigorous, and relevant workforce education and training.

- Education, Innovation, and Efficiency Focus. Leverage resources and educational partnerships to create efficiencies and support development of curriculum and innovative delivery of educational strategies to build a diverse and competitive workforce.

- Workforce Supply and Demand Focus. Research, analyze, and disseminate information related to training capacity, skill gaps, trends, and best practices within each industry sector to support a viable new and incumbent workforce. (Washington State Centers of Excellence, 2017)

__________________

19 These industries include aerospace and advanced manufacturing, agriculture, allied health, education, construction, clean energy, global trade, homeland security, information technology, and marine manufacturing. For more information, see Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges’ (2017).

6.3.2 Sector-Specific Strategies

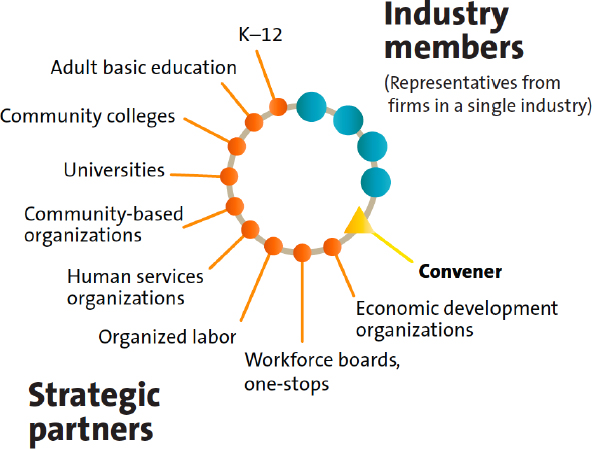

Sector initiatives or partnerships (also known as sector employment programs) are regional partnerships in which a training provider agrees to prepare individuals to work in a specific industry with the expectation that the employers in that industry will hire them. In this way, sector-based strategies integrate the interests of employers, educational institutions, industries, labor, and community organizations to focus on the workforce needs of a strategically important industry within a regional labor market (see Figure 6-1). The training provider is sometimes a community college (e.g., AMTECH) and sometimes a stand-alone training institution (e.g., Per Scholas, described below).

Proponents, which include the National Governors Association (NGA) and the National Skills Coalition, argue that sector strategies can address current and emerging skill gaps; facilitate coordination across city, county, and state lines; and better align programs and resources to improve effectiveness and return on investment (NGA, 2013). Local, state, and federal government agencies that function as champions and conveners of sector-based partnerships can play a constructive role in facilitating skilled technical workforce development.

SOURCE: NGA, 2013.

Evaluations of sector partnerships suggest they have the potential to produce positive outcomes for youth and adults (Maguire et al., 2010; Roder and Elliott, 2014). Using randomized controlled trials, Maguire and colleagues (2010) found that 2 years after the sector-focused training programs they examined (Wisconsin Regional Training Partnership, JVS-Boston, and Per Scholas) ended, workers were earning about $4,500 more than those who did not participate in the sector-specific training (Maguire et al., 2010). One example, Per Scholas in the Bronx, New York, offers on-site training in IT in a 15-week program. An evaluation of Per Scholas showed large and consistent impacts on employment and earnings more than 2 years following the training (Hendra et al., 2016). However, little is known about the long-term impacts of these programs, particularly as workers change jobs and industries restructure, or what is required to build and sustain such partnerships over time. One recent study did use randomized controlled trials to track the long-term outcomes of Project

QUEST, which provides training in several in-demand occupations in San Antonio, with results to be released shortly.20

The NGA’s Center for Best Practices estimates that 1,000 sector partnerships currently are operating across the country and that more than half the nation’s states are exploring or implementing sector strategies (Maguire et al., 2010; Roder and Elliott, 2014). The center traces the origin of the concept to community-based efforts to connect workers to jobs in local industries in the 1980s. In 2010, at the conclusion of a 4-year state sector strategy project led by the NGA, the Corporation for a Skilled Workforce (CSW), and the National Network of Sector Partners (discussed below), more than 25 states were at various stages of implementing sector strategies and funding local initiatives.

In addition, over the past 10 years, the U.S. Department of Labor has funded several initiatives that are consistent with sector strategy principles, including the Sectoral Demonstration Project; the High Growth Training Initiative; the Community Based Job Training Initiative; WIRED; and several American Recovery and Reinvestment Act grants, such as State Energy Sector Partnerships, Energy Training Partnerships, Pathways out of Poverty, and other High Growth and Emerging Industry grants. And under WIOA, local workforce boards are required to use industry sector strategies to carry out training strategies.

Local and national foundations also are supporting the sector strategy concept. The National Fund for Workforce Solutions initiative, for example, involves 22 regional workforce funder collaborations, more than 80 workforce partnerships, and 200 funders. A national association, the National Network of Sector Partners, provides a way for partnerships across the country to connect and learn from each other. In June 2015, the Joyce Foundation announced that it will invest in the Business Leaders United Commitment to Action, which aims to expand the number of sector partnerships by more than 30 percent across all 50 states and to facilitate conversations between local business leaders and federal policy makers about how private, philanthropic, and public dollars can be leveraged to replicate and sustain these partnerships nationally (see Joyce Foundation, 2011).

The NGA, the CSW, and the National Skills Coalition maintain a clearinghouse for state-level sector strategy information.21 Although all state sector strategies are based on the same basic principles, they each reflect local preferences and priorities. One way in which these differences are expressed is in who convenes the partnerships and how. In some states, for example, sector partnerships have been convened by civic leaders in business, community

__________________

20 For a recent review of sector-based training strategies, see Holzer (2015b). See also Elliott and Roder (forthcoming).

21 See http://www.sectorstrategies.org (accessed March 22, 2017).

service, or government, while in others, they have been convened by community colleges or economic development authorities.

6.4 EMPLOYER-BASED TRAINING PROGRAMS

This section reviews training provided by employers to workers through apprenticeship and joint labor–management programs. In many cases, this employer-sponsored training includes coursework at community colleges. American labor unions also have in many instances encouraged their members to support workplace education and training programs as a way to improve workers’ employment security and help them adjust to changing workplace conditions. Connections between employers and workers can be improved as well through better communication of information about the value of credentials and licenses.

6.4.1 Apprenticeship Programs

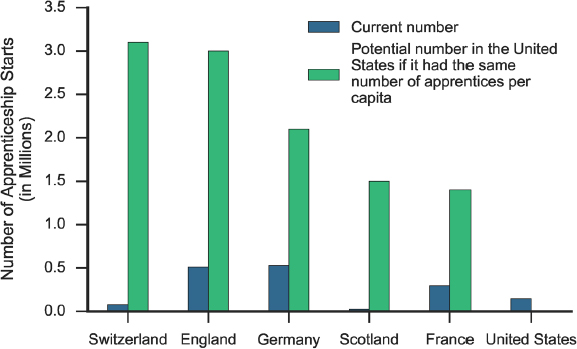

As discussed in Chapter 4, apprenticeships combine occupational education and training with paid on-the-job work experience. Apprenticeships can be either registered or unregistered; approximately 400,000 active apprentices currently are registered with the Department of Labor. Some analysts assert that apprenticeship programs are an underutilized workforce development strategy in the United States (see, e.g., Ayres and Gurwitz, 2014). As Figure 6-2 shows, for example, the number of apprenticeship starts in the United States in 2012 was low relative to the numbers in other developed countries with well-developed apprenticeship programs, such as England, Switzerland, Germany, France, and Scotland.

A number of states have developed apprenticeship programs over the past 10 years, although the impact of such programs has not been rigorously evaluated (see, e.g., Lerman, 2010; Reed et al., 2012). In an effort to close skilled workforce gaps, for example, several programs, such as the Michigan Advanced Technician Training Program (MAT2), the Kentucky Federation for Advanced Manufacturing Education (KY FAME), and Apprenticeship Carolina in South Carolina, have created incentives to expand apprenticeships in their state’s strategically important industries (see the description of Apprenticeship Carolina in Box 6-8).22 The most interesting of these state models move beyond

__________________

22 For information about these programs, see MAT2, http://www.mitalent.org/mat2; KY FAME, http://kyfame.com; and Apprenticeship Carolina, http://www.apprenticeshipcarolina.com.

SOURCE: Adapted from material published by the Center for American Progress. See Ayres, S., and E. Gurwitz. 2014. The underuse of apprenticeships in America. Washington, DC: The Center for American Progress (www.americanprogress.org).

time-based workplace training to integrate dual-learning principles whereby academic courses are linked to workplace training and standardized competency-based certifications.

Many newer forms of apprenticeship in the United States include coursework at a local community college, which leads to an associate’s degree. Employer sponsors provide at least 2,000 hours of paid work per year in the relevant occupation and arrange for their apprentices to receive approximately 150 hours of related instruction. The average apprenticeship lasts 4 years, and

apprentices earn an average of $161,000 during the course of their apprenticeship.

Given the benefits of apprenticeship and the underutilization of these programs noted above, some analysts have suggested that complementary policies and processes that make it convenient and cost-effective for employers to design and implement such programs may be necessary. Currently, it can take as long as 2 years to obtain approval for a new apprenticeship program in some states. Some have suggested offering tax subsidies to employers as a way to offset the costs of developing a new apprenticeship program (Lerman, 2010).

Yet while there is considerable enthusiasm for expanding the apprenticeship concept in the United States, including its extension to a wider range of occupations, some experts caution against directly importing apprenticeship programs from other countries into the United States at a national level.23 They argue that significant institutional differences between the United States and other developed countries make it difficult to replicate other countries’ policies and programs. In addition to the much larger size of the U.S. economy relative to those of European nations, they note the differences in national governance structures and workforce development traditions.24 Countries such as Germany and Switzerland, for example, have stronger traditions as well as formal organizations in place that support employer involvement in education and training. Also in contrast with the policies of many other developed countries, U.S. federal and state-level policies require that most students and workers bear a significant portion of the cost of postsecondary education.

Even so, it may be that the structures of education and workforce policies and programs in some U.S. states are similar in some respects to those found in other developed countries. In such instances, there may be opportunities for state-level policy makers to learn from such countries as Denmark, Germany, Sweden, and Switzerland. Based on the review by Messing-Mathie (2015) commissioned for this study, Box 6-9 lists some key lessons that can be learned from the experience of foreign apprenticeship programs. Further comparative studies, based on a robust methodology, would increase understanding of apprenticeships, the contexts within which they are effective, and the current barriers to their expansion.

__________________

23 Panel 6 at the committee’s 2015 symposium covered the topic of apprenticeships. Presentations, Andrea Messing-Mathie’s paper on apprenticeships, and a webcast of discussions can be found at http://nas.edu/SkilledTechnicalWorkforce.

24 For an overview of the issues, see the section on apprenticeship in Chapter 4. For a comprehensive review of theories, evidence, and comparative issues, see Wolter and Ryan (2011).

6.4.2 Joint Labor–Management Programs

Unions have a prescribed role in job training programs under WIOA, and they have a long history of designing and implementing innovative and effective education and job training programs that potentially can benefit workers, businesses, and local communities. From the earliest days of American trade unions, workers have organized to advocate for local public school systems, and they have been instrumental in the passage of federal vocational education legislation (Stacey and Charner, 1982). Craft unions developed in the 19th century and masters- and journey-level workers created apprenticeship systems that set minimum time periods for training, wage levels, and education requirements (Rorabaugh, 1986). As production and service delivery were expanded and restructured in the 20th century, distinct spheres of influence for managers and workers emerged. Enterprise owners and their professional managers sought to control strategic decision making on

investments, the use of technology, the organization of work, and requirements for technical skills. Workers organized into industrial and service unions to negotiate wage and benefit levels, personnel management practices, and other procedural and process issues salient to the economic interests of their members, including education and training (Thomas and Kochan, 1992).

As the nature and organization of work have continued to evolve, the AFL-CIO, a federation of American labor unions, has encouraged its members to directly sponsor workplace education and training programs as a way of improving workers’ employment security and helping them advance on the job and adjust to changing workplace conditions. In a recent report on these issues, the AFL-CIO argues that many U.S. unions have embraced this challenge and are increasingly collaborating with management to create joint programs and workplace education and training systems, and then institutionalizing these changes through collective bargaining (AFL-CIO, 2016). Box 6-10 describes one example—the Wisconsin AFL-CIO Regional Training Partnership.

More research is needed on joint labor–management strategies for establishing workplace learning systems and on community-based workforce and

economic development initiatives. However, several innovative programs could provide inspiration for skilled technical workforce development in a wide range of areas, including health care, manufacturing, construction, and transportation, and could be adapted to meet the requirements of the nation’s regions (see AFL-CIO, 2016, for an overview of some of these programs). Box 6-11 describes one example of such an innovative technical workforce development program.

6.4.3 The Push for Talent Pipelines

Complementing efforts by labor groups, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation—through its affiliation with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and its federation of more than 3 million employers nationwide—has called upon the business community to play a leadership role in developing a workforce that will meet its strategic business needs (see Box 6-12) (U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, 2014). Working with large employers such as IBM, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation promotes the use of supply chain management principles to create “talent pipelines.” This approach involves linking workforce development requirements to business strategy, as well as reconceptualizing and reorganizing workforce development to nurture and sustain talent, enabling it to evolve to meet business needs over time.

Seeking to address the challenges of skilled technical workforce development, some employers have signed up to participate in the Skills for America’s Future program, a federal initiative designed to foster partnerships between employers and community colleges. In addition, some employers recognize that their employees need support services to improve their skills and pursue education and training opportunities. These employers are fostering a culture that supports continual learning and are adjusting work schedules and assisting employees with child care, transportation, tuition, and other types of expenses. As discussed above and in Chapter 4, data on the extent and effectiveness of these initiatives are scarce, and more research is needed in this area.

6.5 IMPROVING LINKAGES THROUGH BETTER DATA

Better data and better analyses of data are needed to make progress in understanding and addressing the challenges of skilled technical workforce development. Nearly all of the strategies discussed in this report have the potential to improve the flow of information indirectly. Efforts to improve the quality and delivery of skills education and training, for example, will inherently expose students to more information about careers and the education and training required to pursue them. Similarly, better integration across different parts of the workforce development system through dual-enrollment programs, early college schools, sector-based strategies, and career pathways will necessarily involve the sharing of information across educational institutions and employers.

6.5.1 Data Challenges

Extensive gaps exist in the data on technical workforce education and training, as pointed out by Rebecca Rust of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics at the committee’s 2015 symposium. Speaking at the same event, John Dorrer of Jobs for the Future argued that analysts need to improve their ability to mine newly emerging digital jobs databases, as well as existing databases, and called for additional investment in research, particularly policy-relevant research. Courtney Brown of Lumina stated that more data and analyses are needed to understand credentials, career pathways, and supply and demand dynamics in labor markets. Other participants expressed related concerns about the challenges associated with improving labor market data and research, such as privacy laws that can inhibit data sharing, the time and costs associated with information management, and the potential for false or misleading associations that can arise from poorly designed big data repositories and analyses. An additional challenge is ensuring that training programs and educational institutions can use the data collected to keep programs up to date and enable them to evolve with the changing skills required by employers.

Given the complex coordination challenges faced by policy makers, individuals, educators, employers, industry and trade associations, labor unions, and other civic organizations, improvements in the flow of information in skilled technical labor markets are clearly needed. The remainder of this section provides examples of different types of experiments currently under way to improve technical workforce development by identifying and addressing existing information deficits.

6.5.2 Using Big Data

Advances in mathematics, statistics, and the computational sciences make it possible to capture, augment, and analyze data from a broad range of very

different sources. Several contributors to this study argued that applying these developments to policy analysis and research on skilled technical workforce development can provide policy makers with a stronger factual basis for decision making (see Reamer, 2015, for an overview of the issues and findings). In addition, advances in data analytics and information technologies can be used to help consumers make better decisions and create incentives to improve the quality of education and training options.

In the era of big data and new digital tools for collecting information, private firms have learned to mine the web to aggregate or crowdsource data from existing sources. Online job posting and searching, for example, which began in the early 1990s, provides a rich source of data for analysts, researchers, and labor market participants. Software and analytic tools can be designed to crawl through these data, analyze the content, and generate aggregate statistics on job vacancies more often and at finer occupational and geographic scales relative to traditional employer surveys such as the Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS).25

Researchers at Georgetown University estimate that 60 to 70 percent of job postings are now posted online (Carnevale et al., 2014, 2015). However, they state that online job ads may not capture all job openings in all locations. Their analyses suggest that online job ads tend to be biased toward industries and occupations that seek high-skilled workers and workers with 4-year degrees. In their view, data on online job ads are useful in measuring labor demand and honing in on previously inaccessible variables, but these data have limitations. They urge users to exercise caution and utilize this tool in conjunction with traditional data sources. While noting these concerns, contributors to this study highlighted the need for researchers to use a broader set of analytic tools and develop new methodologies to take advantage of the proliferation of online databases.26

6.5.3 Crowdsourcing Information

A primary example of crowdsourced labor market data is the data collected by Burning Glass Technologies (BGT), one of the leading vendors of data on

__________________

25 JOLTS is a monthly survey of employers that was developed to provide information on job openings, hires, and separations. Each month the JOLTS sample consists of approximately 16,000 businesses drawn from 8 million establishments represented in the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages. The publicly available data provide a measure of labor demand across broad industry classifications at the national level or overall aggregate labor demand for four quadrants of the nation.

26 See, for example, the paper by Reamer (2015) commissioned for this study, presentations and discussion in Panel 10 of the committee’s 2015 symposium, and presentations made to the committee in February 2016 at http://nas.edu/SkilledTechnicalWorkforce.

online job ads.27 These data include detailed information on current online job openings updated daily from such sources as job boards, newspapers, government agencies, and employer sites (Burning Glass, 2017). The data provided by BGT allow geographic analysis of occupation-level labor demand by education level and experience level over time. Moreover, the data collection process used by BGT yields a robust representation of hiring in real time.

Such crowdsourcing databases provide valuable information that can be used by educational institutions and workforce development boards. Colleges and technical schools, for example, can use these data to examine the labor market in real time and align their programs with the marketplace, giving students crucial information as they seek jobs. Similarly, labor exchanges in 14 states currently use BGT data to connect workers and employers more efficiently while providing pathways and tools that help workers identify viable careers.

These tools are valuable and increasingly used, but as discussed in the previous section, online data and analytic tools have limitations. For-profit companies own some analytic strategies, such as those offered by BGT, and their data and tools are proprietary. Therefore, maintaining publicly available data and analytic tools, which is encouraged under WIOA and requires federal, state, and local coordination, remains important.

6.5.4 Recent Initiatives

Web-Based Tools

Other web-based tools have enabled private firms to collect data from participants in a variety of markets, including the labor market. For example, Glassdoor, an online jobs and recruiting site with a crowdsourced database, has launched a new open-source map that enables job seekers to see where there are open jobs county by county across the country (The White House, 2014).28 Workers provide information about their experience in interviewing with and working for employer organizations, and registered employers promote job opportunities to potential workers. The database is available online and via mobile applications to registered users.

Public Data Warehouses

The U.S. Department of Labor has supported state efforts to develop the data infrastructures needed to create or improve longitudinal data systems that

__________________

27 Similar data are also collected by Conference Board via its Help Wanted OnLine series.

28 For information about Glassdoor, see http://www.glassdoor.com/index.htm (accessed March 22, 2017).

link employment and earnings data with education, employment service, and training data over time (Davis et al., 2014). Integrating data from K-20 and workforce experience and then warehousing these data allows for the creation of consumer applications that estimate return on investments in education and training. In November 2010, the U.S. Department of Labor launched the Workforce Data Quality Initiative (WDQI), which has provided more than $30 million in grants to 29 states.

Consumer Report Cards

Recently, U.S. Department of Labor grants have focused on creating consumer report card systems (CRCSs).29 As of this writing, five WDQI states—Florida, Minnesota, New Jersey, Virginia, and Washington—had existing CRCSs. Among these states, the structure of the state website and how it is used are generally similar, with each system displaying outcome data for individual programs (Davis et al., 2014).

For example, the New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development partnered with the State University of New Jersey John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers to create a consumer report card website that provides information on occupational training programs in the state (Davis et al., 2014).30 State laws require “training programs at for-profit, public 2-year, and some public 4-year schools that receive state or federal workforce funding to submit records to the state for all of their students” (The White House, 2014). The website makes it possible for students to search by occupation, location, or key word for schools and organizations that provide job training. Students can compare training providers by location, cost, outcomes, and length of training. A results section displays information about former program participants, such as employment rates, retention rates, and average earnings over time.

As another example, Florida continues to expand the longitudinal administrative data infrastructure it developed in the 1970s to integrate K-20 education and workforce data. This infrastructure supports the Florida CRCS—Smart College Choices—which makes it possible to assess and analyze participation in and outcomes of all education and training programs in the state.

__________________

29 WIOA requires eligible training providers, including community colleges, to provide similar consumer/outcome data in the form of a “report card” at the program level.

30 For additional information about the New Jersey Consumer Report Card, see http://www.nj.gov/education/cte/ppcs/students/OnliConRC.shtml. WIOA requires local workforce systems to create career pathways for in-demand industries in the local workforce area. The Department of Labor, Department of Education, and Department of Health and Human Services have agreed upon a framework for career pathways to facilitate meeting this requirement.

Florida’s CRCS provides basic information about education and training programs at the state’s 28 community colleges and 11 public universities. The state is currently preparing to expand the system to include additional institutions and provide more detail about existing options. Consumers can compare such institutional outcomes as completion, continuance, and employment rates and estimated earnings.

6.6 OTHER POLICY INITIATIVES

In addition to linking the key actors in the workforce training and education ecosystem, some policy initiatives help improve the portability and wider recognition of acquired technical skills. Roadmaps that link selected competencies also can help guide students and workers through the education and training they need to address the needs of local industries.

6.6.1 Portable Credentials and Licenses

The NGA’s Center for Best Practices observes that up to 40 percent of community college students enroll in multiple institutions within a 6-year period (The White House, 2014). Efforts to transfer education and training accomplishments and licenses across education and training programs, employers, industries, and geographic boundaries can improve the quality of postsecondary education and training, reduce costs, and improve returns on investment (The White House, 2015, Chapter 2).

To improve the portability of credentials, some states are crafting credit-transfer agreements across their postsecondary systems. The state of Tennessee, for example, “expanded its credit-transfer agreement between 2-year colleges and the public university system. The agreement covers 100 percent of general education requirements and 75 percent of majors at the associate level” (The White House, 2015, Chapter 2). Other initiatives, discussed below, involve standardizing credentials and reducing the burden of licensing requirements.

6.6.2 Standardized Credentials

The past decade has witnessed explosive growth in the number and variety of college degrees, education certificates, industry certifications, occupational licenses, and online badges awarded by various entities and subsequently presented to employers as evidence of specific competencies.31 This pro-

__________________

31 Some experts observe that there is also no national standard for a high school diploma. While the committee believes this is an important issue, a detailed examination of secondary school standards is beyond the scope of this study.

liferation of credentials has created confusion on both sides of the labor market: individuals are unsure which credentials are worth investing in, and employers are questioning the quality and value of the credentials individuals present.

Efforts to standardize credentials focus on harmonizing key features related to quality, portability, and labor market value. For example, a recent partnership between The George Washington University’s Institute of Public Policy and the American National Standards Institute, which is funded by the Lumina Foundation, is reviewing the credentialing activities of more than 48 major credentialing stakeholders, such as business associations; higher education associations; and federal agencies such as the U.S. Departments of Commerce, Education, Labor, Defense, Energy, and Health and Human Services. The partnership has developed definitions, coding schemes, plans for an open metadata registry for posting comparable credentialing information, and pilot projects for testing several registry applications. The implementation plan includes a public–private collaboration of stakeholders that will decide whether and how to take the system to scale and make it sustainable (Crawford and Sheets, 2015).

6.6.3 Licensing Reforms

As discussed in more detail in Chapter 3, a recent study of U.S. occupational licensing patterns and trends reveals significant growth in the number of workers holding an occupational license. When carefully designed and implemented, licensing can offer important health and safety protections to consumers, as well as benefits to workers. However, the current licensing regime in the United States also involves substantial costs, and the requirements for obtaining a license frequently do not align with the skills needed for the job. “Too often, state policy makers do not carefully weigh these costs and benefits when making decisions about whether or how to regulate a profession through licensing” (The White House, 2015, Chapter 2).