Chapter 1

Introduction

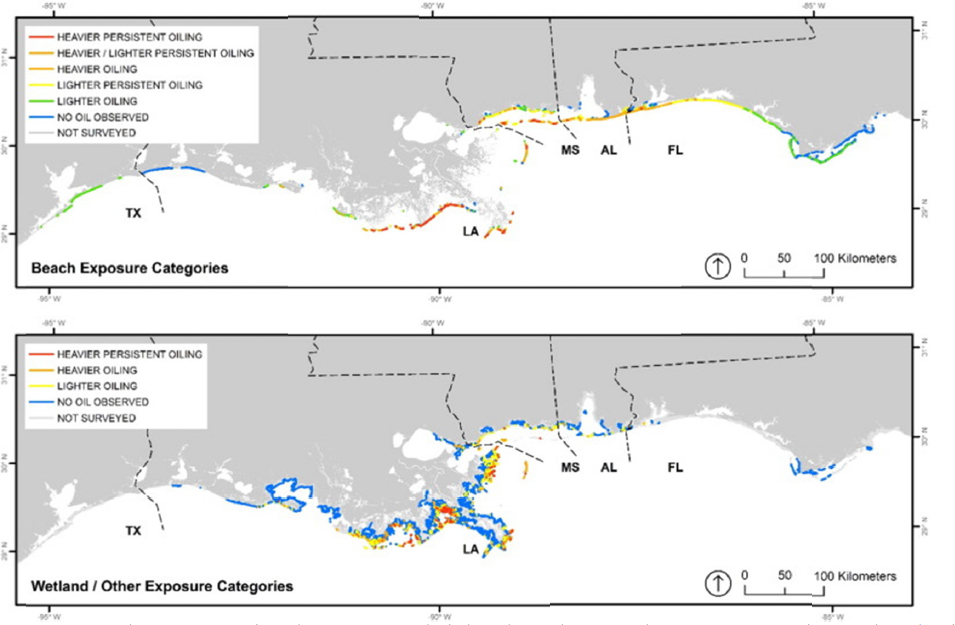

The 2010 Macondo Well Deepwater Horizon (DWH) rig explosion in the Gulf of Mexico claimed the lives of 11 people and resulted in the largest accidental oil spill in U.S. history—an estimated 134 million gallons of oil (DWH NRDA Trustees, 2016). The oil spill contaminated an estimated 180,000 km2 of ocean, 148 km2 of seafloor, and 2,113 km of coastlines, beaches, and estuaries along the shores of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, and Texas (Rabalais, 2014; Nixon et al., 2016). Natural resources suffered direct or indirect damage, notably offshore and coastal wildlife, migratory species, deep sea fauna, submerged aquatic vegetation and shellfish, coastal beaches, and wetlands (NRC, 2013; Rabalais, 2014; Nixon et al., 2016; see Figure 1.1). Gulf Coast communities were also negatively impacted because multiple benefits that people receive from the environment, generally referred to as ecosystem services (MEA, 2005), were also damaged. Losses include an estimated 20% reduction in commercial fishery landings across the Gulf of Mexico and potential damage to 1,770 km of coastal salt marsh wetland that help improve water quality, provide nursery habitats for commercial and recreation fishery species, and protect coastal towns and cities from storm surge and flooding (NRC, 2013).

In the wake of the DWH oil spill and associated legal settlements between the responsible and injured parties, multiple large restoration efforts are being planned and initiated (see Chapter 2). Although the release of oil during the DWH spill was mostly offshore in deep water, many activities are focused on coastal restoration. The massive scale of investment in these restoration efforts underscores the high stakes and associated high expectations to demonstrate damage recovery and restoration progress (Hobbs, 2007; Palmer, 2009; Nilsson et al., 2016). The Gulf region’s coastal and marine ecosystems support some of the nation’s most productive fisheries (Upton, 2011; Sumaila et al., 2012) and many protected species, including marine mammal, turtle, and migratory bird populations. However, these restoration efforts are complicated by the fact that they occur within the context of other ongoing human activities and interconnected environmental change. Almost half of U.S. domestic gas and one-fifth of domestic oil production are extracted from the Gulf, and seven of the nation’s ten busiest ports can be found along the Gulf coast (EIA, 2015). The Gulf region is subject to intense development, industrial pressure, and pollution streams from the third largest drainage system on Earth—the Mississippi watershed—leading to potentially extensive ecosystem degradation. For example, hypoxia has been expanding in the Gulf of Mexico for decades (Turner et al., 2008), oyster biomass has declined by more than 80% over the past century (zu Ermgassen et al., 2012), areal coverage by wetlands in the Gulf decreases at a rate of nearly 1.6% per year (Dahl and Stedman, 2013), and depending on the location along the Gulf coast, 20-100% of seagrass habitat has been lost over the past 50 years (Handley et al., 2007).

Large-scale restoration has been shown to improve biodiversity and human well-being, but the state of restoration practice would benefit from improvements in both its effectiveness and cost efficiency (Alexander et al., 2016). The large infusion of new funding marks an unprecedented opportunity—and a responsibility—to accomplish substantial restoration progress in the Gulf. A key part of this responsibility will be documenting and demonstrating the accomplishments from this sizeable investment in restoration, which depends upon the development of a rigorous, coordinated, and consistent set of monitoring and evaluation approaches (Chapman, 1999; Chapman and Underwood, 2000).

STUDY FOCUS

Recognizing the need for guidance on monitoring and evaluating restoration progress during the early stages of investment in Gulf restoration, the Gulf Research Program of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine sponsored this study to inform monitoring and evaluation of restoration activities in the Gulf of Mexico. An independent Academies committee was asked to identify best practices (i.e., existing, proven, cost-effective approaches) for monitoring and evaluating restoration activities to improve the performance of restoration programs and increase the effectiveness and longevity of restoration projects. The committee was asked to identify

- Current, effective approaches for developing initial and long-term monitoring goals and methods;

- Approaches for determining essential baseline data needs;

- Essential elements of a long-term monitoring framework (including baseline information) that would support current and planned restoration activities in the Gulf of Mexico;

- Additional novel approaches to augment current best practices that could increase effectiveness, reduce costs, ensure region-wide compatibility of restoration monitoring data, and advance the science and practice of restoration; and

- Options to ensure that project, or site-based, monitoring could be used cumulatively and comprehensively to provide region-wide insights and track effectiveness on larger spatial and longer temporal scales.

The report reflects the committee’s consensus findings, based on review of the technical literature, presentations, and discussions at its four meetings, and the experience and knowledge of the committee members in their respective fields. The committee received briefings and input from a range of experts, including restoration practitioners, academics, and representatives of non-governmental organi-zations and state and federal government agencies.

The committee’s task was challenging, given the range of habitats and species subject to restoration, the diversity in project scale or of possible restoration objectives, and the inability to present best monitoring practices for all possible Gulf restoration projects. Thus, the report provides general monitoring guidance that applies across all types of restoration efforts (Part I) and presents more specific guidance for a subset of habitat and species restoration projects that most closely aligned with the committee’s expertise (Part II).

LESSONS FROM PAST RESTORATION PRACTICE

Resource managers have a long history of practicing restoration by manipulating the environment (e.g., SER, 20041; Coleman et al., 2009; for definition see Box 1.1). Restoration practice relies on important assumptions about

___________________

1 See also extensive resources made available by the Society for Ecological Restoration at: http://ser.org/resources.

how a species, habitat, or ecosystem will respond and aims to reconstruct one or more critical elements of an ecosystem back to a more “natural” state to boost provision of some important service or good of that particular ecosystem. For example, an oyster restoration project might involve placing bags of dead oyster shells onto the seafloor to provide clean substrate for naturally occurring oyster larvae to settle based on the assumption that this will lead to the restoration of a self-sustaining oyster reef assuming adequate baseline conditions and larval supply (Coen and Luckenbach, 2000; Baggett et al., 2014).

Despite vast resource investment in restoration of estuaries and coastal habitats in the past, it is not yet customary for projects to rigorously monitor, assess, and document whether restoration activities have met the restoration objectives (or failed to do so) (Ruiz-Jaen and Aide, 2005; Suding, 2011; Halldórsson et al., 2012; Wortley et al., 2013). Furthermore, formal evaluations or meta-analysis across restoration activities are rare (Nilsson et al., 2016). Attempts to learn from the growing number of restoration efforts nation-wide have uncovered major problems due to a pervasive lack of well-defined goals and objectives, statistically insufficient monitoring designs, difficulties in locating documentation about projects including monitoring data and metadata, and a range of other issues (e.g., Palmer et al., 2007; Kennedy et al., 2011). In general, monitoring is a dramatically under-funded activity, and very few environmental management programs, including restoration, monitor ecological or social outcomes (e.g., a global review of conservation programs showed only 20-26% of projects had established monitoring programs [Goldman et al., 2008]). Although restoration monitoring is an integral part of restoration, it is often given a much lower priority than the actual construction or environmental manipulation effort (Thayer et al., 2005).

There are multiple ways that restoration monitoring and assessment activities provide significant value (Groves and Game, 2015). When done well, monitoring and evaluation can describe the environmental, social, ecological, and economic benefits accrued from restoration (De Groot et al., 2013). Especially in the northern Gulf of Mexico, where ecosystems are affected by human activities, management efforts, species interactions, introduced species, and uncertain natural events such as hurricanes, progress of restoration efforts may be uneven and unpredictable from year to year. Considering the substantial investment, Gulf coastal communities and the general public deserve a thorough assessment of whether the stated restoration goals and objectives are achieved, how projects affect their livelihoods, sustenance, and well-being, as well as accountability for how restoration funds are spent (Stem et al., 2005).

Monitoring and evaluation can also help inform decisions about how to make restoration more effective (see Box 1.2; here and in subsequent chapters the committee uses oyster restoration as an example to illustrate general statements). Learning from restoration monitoring can occur through trial and error or, more efficiently, through the structured process of monitoring and formal evaluation and associated adaptive management (see Box 1.3). Carefully designed monitoring can inform decision making to improve future restoration planning and implementation in both the Gulf region and

related coastal ecosystems worldwide (Stem et al., 2005).

Even with growing appreciation for its benefits and importance, conducting effective restoration monitoring and evaluation is difficult and sometimes not considered part of the restoration process (Stem et al., 2005; Kondolf et al., 2007; Lindenmayer and Likens, 2009, 2010; Kennedy et al., 2011; Baggett et al., 2014). There are many reasons why monitoring and assessment activities are difficult to implement or why it is difficult to learn from monitoring activities. Common difficulties with implementing effective restoration monitoring and evaluation efforts include:

- Lack of political will and/or public support (Baker and Eckerberg, 2013);

- Lack of appreciation for the expense of monitoring and/or use of cost-effective measures (Manning et al., 2006);

- Lack of sustained funding, patience, or effort (Manning et al., 2006; Hutto and Belote, 2013 [and references within]);

- Unclear, infeasible, or non-existent vision and program goals (Manning et al., 2006);

- Unclear, untestable, or unbounded project objectives (Kennedy et al., 2011; SER, 2004; Tear et al., 2005; Allen et al., 2011; McKay et al., 2012; Convertino et al., 2013);

- Metrics that are not tied to objectives or inappropriate performance criteria (Kennedy et al., 2011; Neckles et al., 2002; Woolsey et al., 2007; Palmer and Wainger, 2011; Baggett et al.,2014; Kusler and Kentula, 1990; NRC, 2001, 1994; Stelk et al., 2016);

- Insufficient baseline data and/or shifting baselines (Manning et al., 2006; Kusler and Kentula, 1990; NRC, 2001, 1994; Stelk et al., 2016);

- Unsuitable site selection and lack of control and/or reference sites (Kusler and Kentula, 1990; NRC, 2001, 1994; Stelk et al., 2016);

- Inadequate statistical sampling design (Kennedy et al., 2011; Palmer et al., 2007);

- Insufficient or non-existent data management, analysis, archiving, sharing, and/or broader synthesis (Manning et al., 2006; Hutto and Belote, 2013 [and references within]);

- Inaccurate understanding of ecosystem complexity, processes, and linkages (Manning et al., 2006; Kusler and Kentula, 1990; NRC, 2001, 1994; Stelk et al., 2016; Gross, 2003; NRC, 2003a; Mazzotti and Barnes, 2004; Simenstad et al., 2006);

- Lack of clear spatial and temporal boundaries for ecosystems, natural processes, etc (Manning et al., 2006; Charles, 2012);

- Inaccurate understanding of human effects (e.g., harvests) on species and ecosystems (Kennedy et al., 2011);

- Inaccurate understanding of scaling inconsistencies and regional differences (Manning et al., 2006; Kusler and Kentula, 1990; NRC, 2001, 1994; Stelk et al., 2016);

- Lack of a clear understanding and statement of how monitoring information will guide management (Hutto and Belote, 2013 [and references within]; Edwards et al., 2011);

- Lack of formal communication between practitioners and decision makers to incorporate monitoring results (Hutto and Belote, 2013 [and references within]);

- Uncoordinated, ad hoc, multi-objective, and/or small-scale restoration under different authorities at multiple sites (Manning et al., 2006; Kennedy et al., 2011; Edwards et al., 2011);

- Ineffective program management, oversight, and accountability, and lack of clear guidance and requirements for large-scale monitoring (Manning et al., 2006; Kennedy et al., 2011; Kondolf et al., 2007; Edwards et al., 2011);

- Natural/human-induced disasters, disturbances, and unforeseen influences/interactions (Bulleri et al., 2008); and

- Lack of attention to past successes and failures and unwillingness to adapt plans (Manning et al., 2006; Kusler and Kentula, 1990; NRC, 2001, 1994; Stelk et al., 2016; Stem et al., 2005; Suding, 2011).

Thus, the committee’s report offers guidance in the subsequent chapters to overcome these difficulties. In Chesapeake Bay, Kennedy et al. (2011) reported that “of the more than 2,000 [oyster] restoration activities undertaken, a relatively small number were monitored,” and where monitoring did occur, “the kinds and types of data required to determine explicitly the success of restoration were generally not recorded,” severely limiting the authors’ ability to evaluate the effectiveness of oyster restoration. The apparent reluctance to monitor restoration activities may stem from the misconception that monitoring comes at the cost of doing restoration. In contrast, monitoring could inform restoration such that doing restoration would become more cost effective (as described previously in Box 1.2). Without a commitment to rigorous monitoring, it

will be impossible to assess the efficacy of the restoration activities and impossible to improve restoration practice to enhance effectiveness (Lindenmayer and Likens, 2010).

Past experience suggests that restoration practice can be greatly enhanced through properly-designed monitoring and evaluation efforts informed by the latest research in restoration ecology or conservation biology (Stem et al., 2005; Young et al., 2005; Suding, 2011; Groves and Game, 2015). Although restoration ecology has much to offer to improve the efficacy of restoration projects, application of academic research from this relatively nascent field and its intersection with related disciplines—such as ecology, biology, geomorphology, hydrology, and others—is often lagging (e.g., Palmer et al., 2005, Baggett et al., 2014, Neckles et al., 2015).

Furthermore, even when restoration is conducted with appropriate scientific considera-

tions and rigor, restoration does not always achieve the stated objectives, for example reaching comparable biodiversity and ecosystem service provision found in non-degraded ecosystems (Benayas et al., 2009). The fact that many restoration projects lack any monitoring further illustrates the barriers between practice and monitoring and assessment of restoration (e.g., Ruiz-Jaen and Aide, 2005; Kennedy et al., 2011). Improving the effectiveness and longevity of any current and future restoration projects relies on analyzing restoration practice and making results widely available (Palmer et al., 2007). Effective information exchange and stronger feedbacks between the practice and science of restoration monitoring will enhance the efficacy of restoration at a faster rate than either practitioners or researchers could accomplish alone (Young et al., 2005).

REPORT ORGANIZATION

The committee’s report includes discussion of the critical elements in the adaptive management process as it relates to restoration goals and objectives; restoration planning as it pertains to monitoring; monitoring including data stewardship; synthesis; evaluation; and adjustments (as depicted in Figure 1.B). In Chapter 2, the committee reviews and summarizes the restoration goals and initial funding priorities of the major Gulf restoration programs, which are supported by Natural Resource Damage Assessment, Resources and Ecosystems Sustainability, Tourist Opportunities, and Revived Economies of the Gulf Coast States (RESTORE) Act, and National Fish and Wildlife Foundation funds. Chapter 3 addresses a major part of the committee’s task to identify best practices for monitoring and describes current, effective approaches for developing monitoring goals and methods as well as approaches for determining baseline data needs. Chapter 3 addresses this task by presenting general guidance on how to develop a project-level monitoring plan, based on a review of the literature. Important considerations that influence the design of the monitoring efforts are also discussed including recommendations on use of historical data and baseline information, statistical design for sampling, and impacts of scale. To supplement this general guidance, the committee has prepared more specific guidance for restoration monitoring pertaining to a select sub-set of example habitats and species in Part II of the report. To address the committee’s task for long-term monitoring and approaches to augment best practices, in Chapter 4 the committee considers monitoring approaches that go beyond the project duration or geographic scale. In particular, certain restoration efforts will benefit or require monitoring that extend well beyond the duration of the restoration project or beyond the geographic area of a single restoration project. In Chapter 5, the committee presents information on effective data stewardship, including requirements for an effective data management system that provides timely, public data access via web portal. Subsequently, in Chapter 6, the committee discusses how to ensure effective data synthesis and integration can occurs. Both Chapters 5 and 6 are important to addressing the last part of the committee’s charge, which has options to ensuring that project or site-based monitoring could be used cumulatively and comprehensively to track effectiveness at larger spatial scale. Chapter 7 discusses how the information gained from monitoring and synthesis can improve the effectiveness of restoration projects or programs (see Figure 1.B) and discusses adaptive management in greater detail. Finally, examples of good practices for monitoring select habitats (tidal wetlands, oyster reefs, and seagrass beds) and marine living resources (birds, sea turtles, and large marine vertebrates) are provided in Part II of this report.

This page intentionally left blank.