Chapter 2

Gulf Restoration Programs

In this chapter, the major Gulf restoration programs are described to provide context for understanding monitoring and evaluation in light of various program mandates and goals. The chapter begins with a general discussion on setting restoration goals and objectives. Then the respective goals and monitoring plans for the major Gulf restoration plans are outlined, highlighting the importance of clearly defined measurable restoration objectives.

SETTING A VISION, GOALS, AND OBJECTIVES

Effective restoration programs benefit from a clear vision, well defined goals, and measurable objectives (NRC, 2005). A vision can simply be a statement, along with an artistic depiction of the end point conditions of the program, often developed in collaboration with stakeholders (e.g., Petts, 2006). The vision provides the guidance for development of clear sets of goals and objectives, which are critical to program efficacy and project design, implementation, and evaluation (Calow, 2009). Clear goals and objectives specify the desired future with restoration compared to existing conditions (NRC, 1992; SER, 2004; Beck et al., 2011). Restoration goals are typically broad and overarching, such as “return to past ecological conditions,” “address environmental damage,” or “restore ecosystem services” (Baker and Eckerberg, 2016). Such goals are made operational through specific and measureable objectives.

Restoration objectives can be ecological or socioeconomic or both. Ecological restoration objectives might focus on structural (i.e., pertaining to the physical or biological conditions at a project site, such as raising the beach and dune profile to pre-disturbance conditions or increasing marsh-dependent bird populations) and/or functional (i.e., focused on the processes provided by the restored habitat, such as providing suitable nesting conditions for threatened and endangered coastal birds) attributes of the system. Ecological objectives might also focus on restoring species numbers, such as in recovery plans for threatened and endangered species. Socioeconomic objectives focus on the economic or social benefits to people gained from the restoration actions directly (such as employment in habitat construction) or from improved structure or function of the ecological system. In particular, another socioeconomic objective could be the enhancement of ecosystem services supply through protecting and/or enhancing the biophysical structure, function, and processes, and human well-being. This report focuses on monitoring for ecological restoration because the majority of the goals of Gulf restoration programs are primarily to undertake ecological restoration and because the committee was asked by the sponsor to focus on monitoring for ecological restoration. However, the monitoring and assessment of ecosystem services and other socioeconomic aspects are important to consider, especially when explicitly listed as the project’s objective (see NRC, 2012, Chapter 3; NRC, 2013, Chapter 5 for general reference).

Objectives for restoration are ideally chosen based on desired outcomes of a particular project, stakeholder values, and the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of achieving those objectives (NOAA, 2010). Moreover, restoration projects can often strive to achieve multiple objectives. For example, a coastal island can be restored to ameliorate erosion, improve habitat for a threatened species, mitigate pollution impacts, and dampen damaging storm surges for towns or cities onshore. However, some restoration objectives may be irreconcilable. For example, some stakeholders might want to restore a particular beach to provide suitable nesting sites for the conservation of a threatened coastal bird, which might require the exclusion of human access to the particular beach; others might want to restore the same beach for active recreational use. Thus, choosing well-defined guiding objective(s) for restoration is critical to achieving and evaluating the efficacy of a particular project. The importance of setting measurable objectives cannot be overemphasized. A common point of restoration project failure is the lack of an inadequate statement of goals and objectives (e.g., NRC, 1994; Diefenderfer and Thom, 2003; Calow, 2009; NOAA, 2010). Objectives lead to associated actions (restoration efforts), and the environmental and socioeconomic responses to restoration actions are monitored to determine

whether the objectives are being met (see Chapter 7).

GULF RESTORATION PROGRAMS

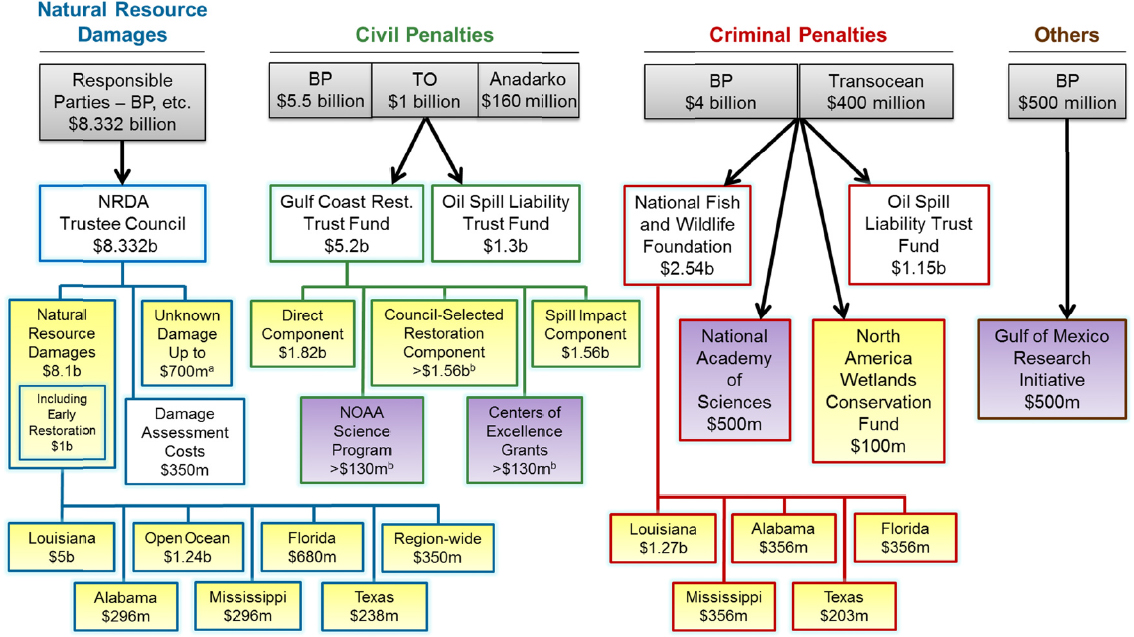

Resolution of natural resource damage, civil and administrative, and criminal claims resulted in the disbursement of funds to a number of councils and programs to administer funds for Deepwater Horizon (DWH)–related restoration in the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 2.1): (1) the Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) Trustee Council; (2) the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council (known as the RESTORE Council); and (3) the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund. These major funding pools are administered separately by programs with different legal frameworks and goals. Despite their differences, these programs strive to support environmental restoration projects in a complementary manner within and across the five Gulf states and in the offshore environment. DWH-related restoration, monitoring, and research funds are also distributed through the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Gulf Research Program, the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) RESTORE Act Science Program, and Gulf state Centers of Excellence (ELI and Tulane, 2014; Ramseur, 2015; USDOJ, 2016; see sources of Figure 2.1 for more information).

Legal Frameworks for the Restoration Programs

Deepwater Horizon NRDA Trustee Council

Under the Oil Pollution Act (1990), natural resource trustees can recover the costs of damage assessment, restoration, and loss of use from potentially responsible parties in response to an oil spill. A natural resource damage assessment is conducted to identify and evaluate injury to natural resources from the release of oil, and the results are used to procure funds from the responsible party to restore damaged resources to the condition that would have occurred if the spill had not happened and to compensate the public for lost natural resources. In October 2015, the Department of Justice announced a settlement with BP Exploration and Production, Inc. (BP) that included $8.1 billion (including $1 billion in early restoration funds) to address natural resources damages and up to an additional $700 million (partly funded from the interest on the $8.1 billion) to address damages that are currently unknown but may be detected in the future. In April 2016, a consent decree from New Orleans federal court resolved civil claims against BP in the largest single-entity federal settlement in U.S. history for a sum of $20.8 billion.1 The Deepwater Horizon NRDA Trustee Council2 therefore acts on behalf of the public to restore natural resources that were directly or indirectly harmed by the oil released into the Gulf of Mexico and compensate the public for their lost use of these resources.

RESTORE Council

The RESTORE Council was created by Congress through the RESTORE Act (2012)3 and charged with overseeing 60% of all civil and administrative penalties related to the DWH oil spill under the Clean Water Act (1972)4 through establishment of the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund (see Figure 2.1). Of the $6.6595 billion settlement (BP, Transocean, and Anadarko), the RESTORE Council manages two categories of restoration funds—the Council-Selected Restoration Component and the Spill Impact Component. The Council-Selected Restoration Component (~$1.6 billion; 30% of funds plus interest) directs funds toward ecosystem restoration projects according to goals and objectives developed in the Initial Comprehensive Plan (RESTORE Council, 2013). The Spill Impact Component ($1.6 billion; 30% of funds) funds implementation of projects developed according to approved individual State Expenditure Plan (SEP) under the RESTORE Act.5 In addition, the Direct Component divides $1.9 billion equally among the states

___________________

1 Department of Justice consent decree: https://www.justice.gov/enrd/deepwater-horizon.

2 The DWH NRDA Trustee Council is comprised of the five Gulf states, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of the Interior, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

3 The Resources and Ecosystems Sustainability, Tourist Opportunities, and Revived Economies of the Gulf Coast States Act was signed into law in 2012 to establish the Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund in the U.S. Treasury Department: https://www.treasury.gov/services/restore-act/Pages/home.aspx.

4 The Clean Water Act was reorganized in 1972 to establish the basic structure for regulating pollutant discharge into United States waters and regulating surface water quality standards: https://www.epa.gov/laws-regulations/summary-clean-water-act.

5https://www.restorethegulf.gov/sites/default/files/NOFA_SEPs_Final_Draft_ver20160524.pdf.

SOURCES: http://response.restoration.noaa.gov/about/media/who-funding-research-and-restoration-gulf-mexico-afterdeepwater-horizon-oil-spill.html, http://www.justice.gov/opa/file/780696/download, http://eli-ocean.org/wpcontent/blogs.dir/2/files/Funding-DH-Restoration-Recovery.pdf, http://eli-ocean.org/gulf/agreement,https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R42942.pdf.

a Unknown NRDA damage includes $232 million plus interest on the $8.1b payment.

b The Comprehensive Plan Component is supplemented by 50% of the interest on RESTORE funds, and the remaining interest is split between the NOAA Science Program and the Centers of Excellence grants.

for “ecological restoration, economic development, and tourism promotion.” The RESTORE Act defines the geographic scope for restoration, which includes the coastal zone (i.e., the coastal waters and adjacent shore land) of the Gulf Coast states, including federal lands; any adjacent land, water, and watersheds within 25 miles of the coastal zones; and all federal waters in the Gulf of Mexico. The Act does not specify a timeframe for expenditure of the funds, but allows the Secretary of the Treasury to decide the amounts to be spent and invested each year from the Trust Fund (Ramseur, 2015).

NFWF Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund

NFWF was awarded $2.5 billion derived from criminal penalties from BP and Transocean to “fund projects benefiting the natural resources of the Gulf Coast that were impacted by the spill” and, specifically, to support projects focused on physical restoration of habitats and ecological functions. Half of the funds are directed for projects in Louisiana to create or restore barrier islands or expand wetland habitat through river diversion projects. The remaining funding is allocated toward natural resources projects in Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, and Texas (see Figure 2.1) to “remedy harm” from the oil spill. As a result of the different legal frameworks and origins of these three major restoration programs, they have different restoration objectives and monitoring requirements.

Goals of the Restoration Programs

These three restoration programs have similar high-level restoration goals.6 All three programs

___________________

6 The Deepwater Horizon Trustee Council’s Programmatic Damage Assessment and Restoration Plan and Programmatic Environmental Impact

aim to restore and conserve habitat as well as replenish and protect living coastal and marine resources. In addition, the NRDA Trustee Council and the RESTORE Council aim to restore water quality and include some socioeconomic components. The NRDA Trustee Council aims to enhance recreation opportunities and the RESTORE Council aims to enhance community resilience and revitalize the Gulf economy. Notably, only the NRDA Trustee Council explicitly lists the provision for monitoring and adaptive management as one of its high-level goals (see below for additional details on monitoring plans).

Although the broad goals articulated in these high-level plans appear similar, the restoration goals established by the RESTORE Council are broader than those set forth by the Oil Pollution Act (1990). The RESTORE Council has the flexibility to fund projects that restore the environment more generally and it is not limited to only ameliorating injury from the DWH oil spill. The RESTORE Council can choose to restore resources injured by the spill, restore degraded ecosystem(s) more broadly (independent of what caused the degradation), or be more forward looking and consider responding to predicted future global changes. The RESTORE Council’s plan also describes fundamental core values underlying the restoration program, including a commitment to “science-based decision-making” and “delivering results and measuring impacts.” The NRDA Trustee Council can support projects that restore or replace injured resources directly injured by the spill, as well as projects that provide resource services of the same type and quality, and of comparable value as those directly injured (See, the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, 33 U.S.C. 2701-2761, Section 990.53[b-c]). The Deepwater Horizon NRDA Trustee Council has adopted monitoring and adaptive management as one of its foundational goals, and can also support monitoring and adaptive management activities; including data collection, analysis, and modeling, that support the planning, implementation and evaluation of restoration for resources injured by the spill. The mission of the NFWF Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund is to conduct or fund projects “to remedy harm and eliminate or reduce risk of future harm to Gulf coast natural resources . . . where there has been injury to, or destruction of, loss of, or loss of use of those resources resulting from the Macondo oil spill.”7

STATES’ PRIORITIES AND STRATEGIES

The Gulf States differ substantially in their range of coastal ecosystem types, DWH-induced damage to these ecosystems, state government goals and priorities for restoration, and experience with developing restoration monitoring protocols. Funding allocations from criminal, civil, and natural resource damage assessment penalties differ among states as well, with some funds distributed equally and others distributed by a specific formula based on the oil-spill impact (see Figure 2.1).

Of the five states, Louisiana coastlines received the majority (65%) of oiling, and 95% of the Gulf’s oiled wetland shorelines are within its borders (Nixon et al., 2016). Louisiana operates under the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, which integrates a range of state agencies and developed a comprehensive restoration plan (Louisiana’s Comprehensive Master Plan for a Sustainable Coast; CPRA, 2012). This restoration plan prioritizes the state’s investment in restoration toward marsh creation, sediment diversion, barrier island restoration, and hydrologic restoration. In support of the Master Plan, Louisiana has made substantial investments in baseline and reference site monitoring, monitoring protocols, model development, and data management. From 2016 to 2018, Louisiana anticipates spending $35 million of state and federal funds to implement its System-wide Assessment and Monitoring Program, $7.4 million for barrier island comprehensive monitoring, and $6.7 million for data management (CPRA, 2012). The state’s Master Plan also requires spending about $3 million per year on restoration planning efforts, and the Plan itself must be updated every 5 years to incorporate improvements in scientific and technical understanding gained from research and ongoing projects. Louisiana’s restoration efforts are supported by the Federal Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection and Restoration Act,8 which was passed in 1990 and mandates to evaluate the effects of specific projects as well as the cumulative and regional effects on the coastal landscape. This restoration program also funds

___________________

Statement: http://www.gulfspillrestoration.noaa.gov/restoration-planning/gulf-plan/; The RESTORE Council’s Comprehensive Plan: https://www.restorethegulf.gov/sites/default/files/Final%20Initial%20Comprehensive%20Plan.pdf.; NFWF’s Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund Funding Priorities: http://www.nfwf.org/gulf/Pages/fundingpriorities.aspx.

7 NFWF’s mission: http://www.nfwf.org/gulf/Documents/bp-oil-spill-agreement-12-1120-v2.pdf.

8 CWPPRA legislation: http://lacoast.gov/new/About.

the state’s Coastal Reference Monitoring System,9 which provides data on multiple reference sites across a range of conditions that can be used when evaluating the results of wetland restoration projects.

The Alabama Gulf Coast Recovery Council has determined restoration priorities to include restoration and mitigation of damage to natural resources, ecosystems, fisheries, marine and wildlife habitats, beaches, and coastal wetlands.10 All proposed state-sponsored RESTORE restoration projects have a strong monitoring component, a monitoring plan is attached to the projects, and monitoring is a line item in the budget for at least 5 years.

The state of Florida is sponsoring ecological and economic/recreational restoration projects, and is focusing on their Ocean Observing System, benthic mapping, non-point source pollution, fisheries-independent monitoring (potentially expanding data collection to other states), and technique effectiveness monitoring. Florida requires monitoring for restoration at (1) project (through permits and grants), (2) medium (e.g., through long-term catalogues and databases), and (3) larger scales (e.g., through geographic information system [GIS] change analysis and modeling). As an example of institutional coordination, The Florida Gulf Consortium11 formed as an agreement among its 23 Gulf coast counties to help meet requirements of the RESTORE Act and develop a State Expenditure Plan.

Mississippi’s restoration priorities emphasize the beneficial use of dredge material to restore eroding beaches, dunes, and coastal islands. The state recently released a restoration plan relying on monitoring data and stakeholder engagement, and funded by NFWF, as well as the Comprehensive Ecosystem Restoration Tool (MCERT Explorer) to support science-based decision making based on landscape, marine, and water quality conditions.12

Early restoration priorities in Texas include land conservation, wetland creation and restoration, coastal island restoration to enhance bird habitat, and coordinating across state lines and with federal agencies. Monitoring programs in support of these restoration programs are under development.13

Restoration Funding Priorities

Based on the early restoration plans and investments from each program, the committee attempted to assess and compare the relative funding allocated to different habitats and living resources in the Gulf of Mexico. For example, the NRDA Trustee Council identifies in the Programmatic Damage Assessment and Restoration Plan 13 different habitats or resources, referred to as Restoration Types, and allocates funding to each in specified regions, referred to as Trustee Implementation Groups (or TIGs, which are the five Gulf States, the open ocean, and region-wide14 (PDARP; DWH NRDA Trustees, 2016). The majority of funding ($4.2 billion) is allocated toward wetlands, coastal, and nearshore habitat restoration, and $4 billion of those funds are directed toward projects in Louisiana. However, $1.2 billion has been allocated toward restoration and monitoring in the open ocean, including projects to improve the condition for marine mammals, sea turtles, sturgeon, birds, and deep benthic communities. An additional $350 million have been set aside for region-wide projects. An agreement in 2011 enabled early restoration for $1 billion to begin as part of the NRDA restoration process to restore injured resources. In December 2015, the RESTORE Council announced the approval of $156.6 million for the first allotment of restoration and planning, described by the Initial Funded Priorities List (RESTORE Council, 2015).

States are also developing expenditure plans for the ~$1.6 billion in RESTORE Spill Impact Component allocation funds, which are available to the states for approved plans according to a specified formula, described in federal regulation.15 Proposed projects must restore and protect Gulf Coast natural resources or economies by undertaking at least one of the activities listed in Box 2.1. NFWF has collaborated with state and federal resource agencies to identify priority categories of restoration, and will continue to refine them as conservation planning and implementation proceeds. As of February 2016,

___________________

9 LA Coastal Reference Monitoring System: http://lacoast.gov/crms2/home.aspx.

10 The Alabama Gulf Coast Recovery Council: http://www.restorealabama.org.

11 The Gulf Consortium is a public entity created in 2012 by inter-local agreement: http://www.flcounties.com/advocacy/gulf-consortium.

12 Mississippi Gulf Coast Restoration Plan: http://www.restore.ms/mississippi-gulf-coast-restoration-plan; MCERT Explorer: http://msrestoreteam.com/NFWFPlan2015/#p=1.

13 Coastal Restoration Funding for Texas from the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill: https://www.restorethetexascoast.org.

14 The term “region-wide” is defined as the Gulf of Mexico regional ecosystem (see PDARP page 3-2).

the Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund has allocated more than $480 million to support 73 projects, and nearly one-third of the funds have been directed toward barrier-island or beach and dune restoration projects. In Louisiana, NFWF has funded the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority to conduct seven projects to date in accordance with their comprehensive Coastal Master Plan (CPRA, 2012). Approximately one-fourth of the funding to date has supported wetland restoration projects, with additional funding for coastal habitat improvements, watershed management projects, land conservation, and oyster reef restoration.16

Restoration Monitoring

NRDA Restoration Monitoring Guidelines

The Programmatic Damage Assessment and Restoration Plan (PDARP, DWH NRDA Trustees, 2016) embraces the development of carefully designed monitoring programs to support adaptive management and restoration decision making: “Given the unprecedented temporal, spatial, and funding scales associated with this restoration plan, the Trustees recognize the need for a robust monitoring and adaptive management framework to measure the beneficial impacts of restoration and support restoration decision-making. In order to increase the likelihood of successful restoration, the Trustees will conduct monitoring and evaluation needed to inform decision-making for current projects and refine the selection, design, and implementation of future restoration. This monitoring and adaptive management framework may be more robust for elements of the restoration plan with higher degrees of uncertainty or where large amounts of restoration are planned within a given geographic area and/or for the benefit of a particular resource” (DWH NRDA Trustees, 2016, Appendix 5E). The DWH NRDA Trustees (2016) state that monitoring guidelines will be developed in support of restoration, including “the establishment of a suite of core parameters and monitoring methods (i.e., minimum monitoring standards) to be used consistently across projects in order to facilitate the aggregation of project monitoring results and the evaluation of restoration progress for each restoration type.”

Project monitoring is required by the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 for restoration activities funded by NRDA to ensure compliance with applicable environmental statutes, evaluate project success, and assess the need for correction. According to the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (33 U.S.C. 2701-2761), DWH NRDA monitoring plans must include the following elements: (1) “measurable restoration objectives that are specific to the injury and the desired project outcome”; (2) “performance criteria that are used to determine project success or the need for corrective actions”; and should include (3) information on “duration and frequency, sampling level, reference sites, and costs.” To encourage improved monitoring, NRDA Trustees supported Early Restoration projects with monitoring frameworks and conceptual plans developed by project type.17 Due to the unprecedented temporal, spatial, and funding

___________________

16 List of funded NFWF projects: http://www.nfwf.org/gulf/Pages/gulf-projects.aspx.

17 For more information, please see DWH NRDA Trustees (2016). For a list of the 13 NRDA restoration project types, see http://www.gulfspillrestoration.noaa.gov/2016/02/update-on-the-comprehensive-restoration-plan-for-the-gulf-of-mexico.

scales of the restoration that will be undertaken following the DWH oil spill, the NRDA Trustee Council has provided a more robust monitoring and management framework for long term restoration than that common in prior NRDA cases (DWH NRDA Trustees 2016, Appendix 5E). This framework includes monitoring the function of restoration projects and determining the need for corrective actions, setting monitoring and data standards to encourage consistency across projects, and supporting targeted data collection to inform restoration decision-making (DWH NRDA Trustees 2016, Appendix 5E). Restoration frameworks provide information and lessons learned that will be used to develop guidelines for standardized monitoring, including consistent parameters and methods to enable project aggregation by restoration type, as well as plans for adaptive management and resource-specific strategies (DWH NRDA Trustees, 2016, Appendix 5E).

RESTORE Council Restoration Monitoring Guidelines

Based on the Initial Comprehensive Plan (RESTORE Council, 2013), a range of monitoring can be anticipated for the RESTORE Council’s restoration efforts. In addition to supporting science-based decision making and measuring restoration impacts, monitoring will be necessary to meet the RESTORE Council’s annual reporting required by Congress and the public. The applications to the RESTORE Council for funding are required to include methods for measuring, monitoring, and evaluating the outcomes and impacts of funded projects, programs, and activities. In December 2015, the RESTORE Council approved funding for a $2.5 million project to conduct an inventory and gap analysis of existing data and monitoring systems; develop and provide recommendations to the Council for common standards and protocols; establish metrics needed to measure influence of water quality and habitat restoration; establish baseline conditions; and provide recommendations to the Council on how to address gaps and future needs. The project is a partnership between NOAA and the USGS, and actively incorporates all five states’ Council Members. In addition, the Council is funding another project through the state of Alabama for the Gulf of Mexico Alliance (GOMA) to further develop a Monitoring Community of Practice using expertise from existing GOMA Priority Issue Teams. These two Council-funded projects are closely connected and involve other government agencies, states, academia, nongovernmental/non-profit organizations, business, and industry, to develop “basic foundational components for Gulf region-wide monitoring in order to measure beneficial impacts of investments in restoration.”18 While the RESTORE Council is committed to adaptive management (RESTORE Council, 2013), no guidance is currently in place with regard to adaptive management for RESTORE Council administered projects.

NFWF Restoration Monitoring Guidelines

NFWF requires pre- and post-project monitoring to assess performance and achievement of specific goals proposed by applicants, as well as to inform adaptive management for each project and as a contribution to regional efforts, if possible (J. Porthouse, personal communication). Thus, projects funded by the Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund primarily need monitoring components to include evaluation of project construction/implementation, effect(s) on identified stressors, and ecological outcome(s). Secondary and more long-term purposes are to support adaptive management, provide lessons learned for similar projects, inform programmatic evaluation, and contribute to the understanding of regional baseline conditions (J. Porthouse, personal communication). All projects are expected to include pre- and post-implementation monitoring and adaptive management plans that are consistent with other regional programs such as the NRDA and RESTORE programs. Restoration projects are also expected to plan for data storage, make the data available to the public, and archive data for future use. Adaptive management plans for projects need to either be included in a proposal or are prepared with project development funding from NFWF. In addition, all data collected in association with Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund projects is expected to be publicly available as soon as possible after collection and quality assurance/quality control (J. Porthouse, personal communication).

___________________

18 RESTORE-funded Council Monitoring and Assessment Program Development project: https://www.restorethegulf.gov/sites/default/files/FPL_FINAL_Dec9Vote_EC_Library_Links.pdf (p.228).

RELATED SCIENCE PROGRAMS

Civil and criminal penalties from the DWH disaster were also paid by responsible parties to fund science programs that can inform restoration practice in the Gulf of Mexico (see purple-highlighted boxes in Figure 2.1). The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Gulf Research Program; the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Science, Observation, Monitoring, and Technology Program (known as the NOAA RESTORE Act Science Program); the RESTORE Act state-based Centers of Excellence; and the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative will therefore work to enhance relevant science available to the restoration programs described above, to restoration researchers, and to the Gulf community in general. Another science program operating with DWH-related funds is the Gulf of Mexico Universities Research Collaborative (GOMURC),19 which coordinates over 80 research institutions to support science and education.

Gulf Research Program

The Gulf Research Program operates over a 30 year timeframe (2013-2043) to support studies, projects, and other activities; and is focused on enhancing oil system safety, human health, and environmental protection in the Gulf of Mexico (as well as other U.S. outer continental shelf areas). The organization seeks to “improve understanding of the region’s interconnecting human, environmental, and energy systems and fostering application of these insights to benefit Gulf communities, ecosystems, and the Nation.”25 The Gulf Research Program will address this mission by supporting research and development, education and training, and environmental monitoring. Its strategies are therefore to pursue opportunities to enhance “long-term, cross boundary perspectives; science to advance understanding; science to serve community needs; synthesis and integration; coordination and partnerships; and leadership and capacity building.”25 Initial funding has supported early-career research fellowships, science policy fellowships, and exploratory grants, as well as projects to build capacity in Gulf communities, enhance local resilience and well-being, and synthesize environmental monitoring data. The Gulf Research Program has also held a number of workshops to identify funding opportunities, and produced subsequent reports on community resilience and health, monitoring ecosystem restoration and deep water environments, and middle-skilled workforce needs.20

NOAA RESTORE Act Science Program

The NOAA RESTORE Act Science Program does not have a specified timeframe of operation. The Program’s mission is “to carry out research, observation, and monitoring to support, to the maximum extent practicable, the long‐term sustainability of the ecosystem, fish stocks, fish habitat, and the recreational, commercial, and charter‐fishing industry in the Gulf of Mexico.” NOAA administers the program with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the RESTORE Council to provide the science in support of “healthy, [. . .] sustainable [. . .] habitats and living resources (including wildlife and fisheries).” Program parameters allow for funding towards the following research activities and species: (1) “marine and estuarine research, ecosystem monitoring, and ocean observation; (2) data collection and stock assessments; (3) pilot programs for fishery independent data and reduction of exploitation of spawning aggregations; (4) cooperative research; and (5) eligible fish species including all marine, estuarine, and aquaculture species in State and Federal waters of the Gulf of Mexico.” The Program especially values long-term projects, collaborative efforts, and partnerships within the Gulf region, as well as coordination with related research activities and existing federal and state science and technology programs. The Program operates according to its Science Plan,21 which details ten long-term research priorities that will guide its support for future science funding opportunities, along with mission alignment, stakeholder input, topics addressed by other funding programs, and new advancements.22 Recent investments from the first federal funding opportunity ($2.7 million) have been allocated to seven projects to date that will evaluate indicators of ecosystem conditions and services; identify

___________________

19 GOMURC engages academia in response to and recovery from the DWH spill: http://gomurc.usf.edu.

20 Gulf Research Program: http://www.nationalacademies.org/gulf/index.html.

21 NOAA RESTORE Act Science Program Science Plan: http://restoreactscienceprogram.noaa.gov/wpcontent/uploads/2015/05/Science-Plan-FINAL-for-website.pdf.

22 NOAA RESTORE Act Science Program: http://restoreactscienceprogram.noaa.gov.

data gaps; develop conceptual ecological and ecosystem models to assess the monitoring and management utility of observation networks; and assess and develop monitoring recommendations in the Gulf.23

RESTORE Act Centers of Excellence

The Gulf Coast Restoration Trust Fund also supports the Centers of Excellence Research Grants Program for the five Gulf states with 2.5% of the civil penalties deposited into the fund plus 25% of interest earned. Funds can be used to establish Center(s) through awards to educational institutions, nongovernmental organizations, and consortia; and by the Centers to advance science, technology, and monitoring efforts. Eligible disciplines include “(1) coastal and deltaic sustainability, restoration, and protection, including solutions and technology that allow citizens to live in a safe and sustainable manner in a coastal delta in the Gulf region; (2) coastal fisheries and wildlife ecosystem research and monitoring in the Gulf Coast region; and (3) offshore energy development, including research and technology, to improve the sustainable and safe development of energy resources in the Gulf of Mexico, sustainable and resilient growth, economic and commercial development in the Gulf Coast region; and/or Comprehensive observation, monitoring, and mapping.”24

Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative

The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI) was created as an independent research program with funds directly from BP to better understand the effects of oil pollution and related stressors on ecosystem and public health in the Gulf. Its main themes are physical movement of oil and dispersants, degradation and ecosystem interaction, environmental effects, and technology to improve response, remediation, and human health effects. The initiative is committed to “investigate the impacts of the oil, dispersed oil, and dispersant on the ecosystems of the Gulf of Mexico and affected coastal States in a broad context of improving fundamental understanding of the dynamics of such events and their environmental stresses and public health implications. The GoMRI will also develop improved spill mitigation, oil and gas detection, characterization and remediation technologies.” Regardless of the source of funds, GoMRI research results will be published in peer-reviewed journals with no BP approval requirement.25

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

As discussed in detail above, the structure established to administer funds for projects and programs that are designed to restore and monitor species, habitats, and ecosystems after the DWH disaster (see Figure 2.1) delineates three major Gulf restoration programs.26 A number of related science programs are also playing important roles in support of informed restoration and monitoring efforts. These organizations intend to work in a coordinated manner to foster collaboration and further efforts to synthesize knowledge and practice that can help improve the condition of the Gulf. Each funding program answers to different mandates and as a result has slightly different, but clearly articulated, broad restoration goals.

However, specific, measurable restoration objectives were not as well delineated or identified. Instead, program goals were frequently linked directly to restoration actions, without an explicit description of what the overall program intends to accomplish. For example, “restoring 100 acres of tidal marsh to increase marsh bird abundance by 10% in 5 years” is a hypothetical, measurable objective. Other illustrative examples of measurable objectives are provided in Part II of this report. Measurable objectives are required for program assessments and for improving restoration effectiveness (Kentula et al., 1992; NRC, 2005; Kapos et al., 2010). Thus, the absence of clearly articulated, measurable objectives could hinder effective program management in the Gulf. A notable exception is found within the PDARP (DWH NRDA Trustees, 2016), which included separate, more-specific, often measurable restoration “goals” for each of the thirteen restoration types in addition to the

___________________

23 Research funded by the NOAA RESTORE Act Science Program: https://restoreactscienceprogram.noaa.gov/research.

24 Centers of Excellence Research Grants Program, administered by the U.S. Department of the Treasury: https://www.treasury.gov/services/restoreact/Pages/COE/Centers-of-Excellence.aspx.

25 In 2010, BP committed $500 million over a 10-year period to create GOMRI: http://gulfresearchinitiative.org.

26 See the following documents for information on project funding: DWH NRDA Trustees (2016), RESTORE Council (2015), NFWF list of funded projects (http://www.nfwf.org/gulf/Pages/fundingpriorities.aspx).

five broad restoration goals noted previously in this chapter. Furthermore, NFWF has awarded funds for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to develop an “integrated, far-reaching planning effort” for restoration and conservation for Florida’s coastal, natural resources.27 It appears that this “science-based” planning effort will develop the needed goals and objectives against which restoration progress can be assessed. As discussed in Chapters 3 and 7 of this report, specific, measurable restoration objectives are needed, particularly for the RESTORE Council and NFWF, to support performance assessment and support adaptive management. For specific examples of such objectives and metrics, see Part II of this report.

Moreover, in addition to ecological outcomes, when appropriate, measurable objectives are also needed for socioeconomic outcomes. For example, NRDA, RESTORE, and some state programs have high-level goals that suggest intended outcomes for ecosystem services, such as commercial and recreational fishery benefits, improved recreational opportunities at beaches and other habitats, improved water quality for coastal communities and increased community resilience to storms and floods. The degree to which these human benefits will be targeted and monitored can be significantly clarified by the development of specific objectives targeting socioeconomic outcomes, in addition to those developed for environmental outcomes.

Therefore, the committee concludes that Gulf restoration programs need to develop clear and measurable ecological and, where appropriate, socioeconomic objectives at project and program levels to guide monitoring plans and against which to evaluate restoration progress. Given the similarities in the strategic goals of the Gulf restoration programs, restoration objectives need to be considered holistically across these three programs to ensure compatibility of efforts and to ensure that restoration and restoration monitoring efforts can yield the greatest synergies.

___________________

27 Florida Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund Restoration Strategy: http://www.nfwf.org/gulf/Documents/flrestoration%20planning-15oc.pdf.