4

Context Matters

The production of high-quality economic evidence is necessary—but not sufficient—to improve the usefulness and use of this type of evidence in investment decisions related to children, youth, and families. Equally important is attention before, during, and after economic evaluations are performed to the context in which decisions are made. Consumers of the economic evidence produced by these evaluations will inevitably consider such factors as whether the evidence is relevant and accessible and whether meaningful guidance is provided on how to apply the evidence within existing organizational structures, as well as personnel and budget constraints. Consumers also will consider the influence on investment decisions of broader factors such as political pressures and value-based priorities. As discussed in Chapter 2, moreover, whether evidence (including economic evidence) is used varies significantly depending on the type of investment decision being made and the decision maker’s incentives, or lack thereof, for its use (Eddama and Coast, 2008; Elliott and Popay, 2000; Innvaer et al., 2002; National Research Council, 2012). In addition, a decision maker may be faced with the pressing need to act in the absence of available or relevant evidence (Anderson et al., 2005; Simoens, 2010).

Apart from economic evaluations, decision makers rely on many other sources to inform their decisions, including expert opinion, community preferences, and personal testimonies (Armstrong et al., 2014; Bowen and Zwi, 2005; Orton et al., 2011). Reliance on these sources rises when the empirical evidence does not clearly point the decision maker in one direction or when there are conflicting views on the topic at hand (Atkins et al., 2005). The influence of a given type of evidence also may differ by

the stage of the decision making process (i.e., policy agenda setting, policy formulation, policy implementation) or its objective (e.g., effectiveness, appropriateness, implementation) (Bowen and Zwi, 2005; Dobrow et al., 2004, 2006; Hanney et al., 2003; National Research Council, 2012).

With some noteworthy exceptions, efforts to improve the use of evidence have focused on the use of research evidence in general rather than on the use of economic evidence in particular. Even with this broader focus, however, the research base on the factors that guide decisions and on reliable strategies for increasing the use of evidence is scant in the United States (Brownson et al., 2009; Jennings and Hall, 2011; National Research Council, 2012). The committee therefore based its conclusions and recommendations in this area on multiple sources: the emerging literature on processes for improving evidence-based decision making, relevant literature on the use of economic evidence from other countries, the expertise of the committee members, and two public information-gathering sessions (Appendix A contains agendas for both of these sessions). Many lessons learned from broader efforts to understand and improve the use of research evidence apply to the use of economic evidence in decision making.

This chapter organizes the committee’s review of contextual factors that influence the usefulness and use of evidence under three, sometimes overlapping, headings: (1) alignment of the evidence with the decision context, which includes the relevance of the evidence, organizational capacity to make use of the evidence, and the accessibility of reporting formats; (2) other factors in the use of evidence, which include the role of politics and values in the decision making process, budgetary considerations, and data availability; and (3) factors that facilitate the use of evidence, which include organizational culture, management practices, and collaborative relationships. The chapter then provides examples of efforts to improve the use of evidence, illustrating the role of the various factors discussed throughout the chapter. The final section presents the committee’s recommendations for improving the usefulness and use of evidence.

ALIGNMENT OF EVIDENCE WITH THE DECISION CONTEXT

Optimal use of evidence currently is not realized in part because the evidence is commonly generated independently of the investment decision it may inform (National Research Council, 2012). Economic evaluations are undertaken in highly controlled environments with resources and supports that are not available in most real-world settings. The results, therefore, may not be perceived as relevant to a particular decision context or feasible to implement in a setting different from that in which the evidence was derived. In addition, findings from economic evaluations may be reported in formats that are not accessible to consumers of the evidence.

Relevance of Evidence to the Decision Context

“Often there is not an evaluation that addresses the specific questions that are important at a given time. Usually what is used are evaluations that have already been done, internally or externally, that may or may not have answered the current questions.”

—Dan Rosenbaum, senior economist, Economic Policy Division, Office of Management and Budget, at the committee’s open session on March 23, 2015.

“We think a lot about the question of scalability. You may have something with strong evidence that works really well in New York City. That same approach may not work as well in a small border town in Texas where your work is shaped by a very different set of local factors.”

—Nadya Dabby, assistant deputy secretary for innovation and improvement, U.S. Department of Education, at the committee’s open session on March 23, 2015.

The perceived relevance of an evaluation to a specific decision influences whether the evidence is used or cast aside (Asen et al., 2013; Lorenc et al., 2014). Yet producers and consumers of evidence generally operate in distinct environments with differing terminology, incentives, norms, and professional affiliations. The two communities also differ in the outcomes they value (Elliott and Popay, 2000; Kemm, 2006; National Research Council, 2012; Oliver et al., 2014a; Tseng, 2012). As a result, the evidence produced and the evidence perceived to be relevant to a specific decision often differ as well.

Evidence is most likely to be used when the evaluation that produces it is conducted in the locale where the decision will be made and includes attention to contextual factors (Asen et al., 2013; Hanney et al., 2003; Hoyle et al., 2008; Merlo et al., 2015; Oliver et al., 2014a). Decision makers want to know whether a given intervention will work for their population, implementing body, and personnel. Each of these factors, however, often differs from the conditions under which the evaluation was conducted. Even methodologically strong studies that demonstrate positive effects under prescribed conditions can be and often are discounted in the absence of research indicating that these outcomes can be achieved under alternative conditions (DuMont, 2015; Nelson et al., 2009; Palinkas et al., 2014).

One way to enhance the relevance—and thus the use—of evidence is to gain a more thorough understanding of the decision chain, the specific decision to be made, when it will be made, where responsibility for making it lies, and what factors will influence that person or organization (National Research Council, 2012). It is also useful for producers of economic evidence and intermediaries (discussed later in this chapter in the section on

collaborative relationships) to consider the intended purpose of an existing intervention; the details of its implementation and administration; the culture and history of the decision making organization, particularly with respect to its use of various types of evidence; and the community in which the intervention is set (Armstrong et al., 2014; Eddama and Coast, 2008; van Dongen et al., 2013).

Ideally, economic evaluation goes beyond rigorous impact studies and associated cost studies to examine impact variability, particularly whether there are impacts for different settings, contexts, and populations, and whether and what adaptations can be effective; systems-level supports required for effective implementation; and the cost of implementation at the level of implementation fidelity required. Policy makers and practitioners attend not only to impacts but also to how to achieve them and the extent to which externally generated evidence applies within their own context (Goldhaber-Fiebert et al., 2011).

CONCLUSION: Evidence often is produced without the end-user in mind. Therefore, the evidence available does not always align with the evidence needed.

CONCLUSION: Evidence is more likely to be used if it is perceived as relevant to the context in which the investment decision is being made.

Capacity to Acquire and Make Use of Evidence

A key factor in promoting the use of economic evidence is ensuring that end-users have the capacity to acquire, interpret, and act upon the evidence. That capacity falls into two categories: the capacity to engage with and understand the research, and the capacity to implement the practices, models, or programs that the research supports. In both cases, that capacity can be developed internally in an agency or implementing organization or it can be supported through intermediaries who help translate evidence for decision makers or offer support to those implementing interventions with an evidence base.

Organizational Capacity to Acquire and Interpret Evidence

“We hire consultants more often than not [to access and analyze evidence] because we don’t always have the capacity to do so, which means we have to also find a funding source to make that possible.”

—Uma Ahluwalia, director, Montgomery County, Maryland Department of Health and Human Services, at the committee’s open session on March 23, 2015.

“We’ve heard from some program administrators who would like to be able to have cost-benefit information, but lack the capacity to [access the necessary data]. In addition, agencies do not always have the expertise needed to conduct these kinds of data analyses.”

—Carlise King, executive director, Early Childhood Data Collaborative, Child Trends, at the committee’s open session of June 1, 2015.

As public pressure for accountability and efficiency grows, leaders in both public and nonprofit settings are increasingly called upon to collect, analyze, and interpret data on their agency’s effectiveness. Similarly, policy makers and funders are expected to make use of economic data in making decisions. Yet many of these stakeholders lack the capacity, time, or expertise to perform these tasks (Armstrong et al., 2013; Merlo et al., 2015). For example, Chaikledkaew and colleagues (2009) found that 50 percent of government researchers and 70 percent of policy makers in Thailand were unfamiliar with economic concepts such as discounting and sensitivity analysis.

Within public and private or nonprofit agencies across multiple sectors, decision makers may have had little training in research and evaluation methodology, which limits their ability to understand and assess the research base and use it to inform policy or practice (Brownson et al., 2009; Lessard et al., 2010). One of the only studies of its kind on the training needs of the public health workforce in the United States identified large gaps in these decision makers’ competence in the use of economic evaluation to improve their evidence-based decision making, as well as their ability to communicate research findings to policy makers (Jacob et al., 2014). Their ability to review the entire research base in the area of interest also may be limited by constraints of time and access. As a result, decision makers are vulnerable to presentations of evidence from vested interest groups that offer a limited view of what the evidence does and does not show.

Clearinghouses of evidence-based practices, discussed in the section below on reporting, can make existing knowledge accessible to many users on a common platform. However, decision makers would have difficulty summarizing all the evidence relevant to a particular decision at hand. Thus, organizations developing and implementing interventions need to have the internal or external capacity to interpret the evidence and determine how it applies to their specific context and circumstances.

One approach to building greater capacity for the analysis and use of research evidence, including economic evidence, is to incorporate stronger training on those topics into undergraduate and graduate curricula, as well as into other learning opportunities, including on-the-job or work-based learning and fellowships for future leaders and those seeking to inform deci-

sion making (Jacob et al., 2014; National Research Council, 2012). Senior executive service training in the federal government, for example, could include training in the use of economic evidence for federal executive leaders. Fellowship programs sponsored by philanthropies, government organizations, or other institutions could include training or practicums focused on the use of economic evidence. Graduate programs for those pursuing careers in government or service organizations or those seeking to influence decision makers—such as programs leading to a master’s degree in public policy, public administration, public health, social work, law, journalism, or communications—could include coursework related to the acquisition, translation, and use of evidence of all types, including economic evidence. Finally, human resources agencies serving employees who work on interventions for children, youth, and families could provide training and opportunities for applied learning in the use of research evidence, including how to access and acquire the evidence, how to judge its quality, and how to apply it in decision making. An example of such capacity is provided in Box 4-1.

CONCLUSION: Capacity to access and analyze existing economic evidence is lacking. Leadership training needs to build the knowledge and skills to use such evidence effectively in organizational operations and decision making. Such competencies include being able to locate economic evidence, assess its quality, interpret it, understand its relevance, and apply it to the decision context at hand.

Capacity to Implement Evidence-Based Interventions

“The issue of implementation is huge. Our own research suggests that the quality and extent of implementation of any given program is at least as important in determining effects, or in many cases more important, than the actual variety of the program implemented locally. The question of whether or not one can reasonably expect the kinds of effects that the background evidence suggests is very much an open question and has a great deal to do with the quality of the monitoring systems, implementation fidelity, local resources, and a huge number of contextual factors that have to do with what is actually put on the ground under the label of one of these programs.”

—Mark W. Lipsey, director, Peabody Research Institute, Vanderbilt University, at the committee’s open session on June 1, 2015.

“The evidence conversation is tilted entirely toward the evidence of effectiveness and efficacy, and we need a better understanding of the use of evidence in implementation. There are good examples of those kinds of

BOX 4-1

Building Capacity to Seek and Use Evidence: An Example

Kaufman and colleagues (2006) provided training and technical assistance in support of a community awarded a federal Safe Start demonstration grant for an integrated system of care designed to reduce young children’s exposure to violence. Their efforts represent an example of a university-community partnership that successfully improved the community’s capacity to seek and use scientific evidence in its local decision making. Although the objective was to increase the community’s acceptance of program evaluation data, the lessons learned could inform similar efforts to build stakeholders’ capacity to use economic evaluations as an additional tool to guide investment decisions.

The academic evaluators effectively educated policy makers, community leaders, and providers on the benefits of scientific evidence by engaging in a number of efforts, including (1) spending time outside of the university setting and participating actively in community meetings and forums to build relationships and trust, (2) delivering on research that the community identified as critical to its operations, (3) providing continual feedback on research findings to selected target audiences using strategies and mechanisms that reflected how those audiences consumed information, (4) embedding training and technical assistance in the use of evidence in all aspects of the initiative to promote the evidence’s broad utility, and (5) participating in project leadership meetings to ensure that the evidence was informing management decision making in real time. The investment of time and resources by the researchers led to an observable, sustained shift in the community’s capacity to incorporate evidence at multiple levels of program management and policy making.

systems. As others have pointed out, they depend a lot upon the capacity of the people implementing.”

—John Q. Easton, distinguished senior fellow, Spencer Foundation, at the committee’s open session on June 1, 2015.

Even if an organization has the capacity to access and analyze evaluation evidence, it may not have the infrastructure and capacity to support effective implementation of evidence-based interventions (Jacob et al., 2014; LaRocca et al., 2012). For instance, if an evidence-based intervention requires a level of professional development that no one can afford, or a workforce that is unavailable in most communities, or much lower caseloads than are found in existing systems, it will not be well implemented.

Implementation fidelity is critical to ensuring that economic benefits are realized. Funding is essential not only for the cost of the intervention but

also for the cost of the supports required to implement it. As discussed in Chapter 3, economic evaluators can break those costs out explicitly, since they may need to be funded from different sources. For instance, practitioners’ time may be billable to Medicaid, but the cost of building a quality assurance system to monitor implementation may not be.

Incorporating economic evidence into conceptual frameworks and models of implementation may improve the dissemination and use of the evidence. These models have been developed to study some of the implementation issues discussed above, but little attention has been given to whether economic evidence should be incorporated into the models and if so, how. In the development of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, for example, Damschroder and colleagues (2009) found that intervention costs were considered in only 5 of 19 implementation theories they reviewed. Although they decided to include costs in their framework as one of several intervention characteristics that affect implementation, they note that “in many contexts, costs are difficult to capture and available resources may have a more direct influence on implementation” (p. 7) without recommending increased attention to cost assessment in the development of new interventions. Similarly, a conceptual model developed by Aarons and colleagues (2011) includes funding as a factor affecting all phases of the implementation process but fails to consider that intervention costs could also play an important role in implementation, especially considering that funding must be commensurate with costs. In contrast, Ribisl and colleagues (2014) propose a much more prominent role for economic analysis in the design and implementation of new interventions. They argue that cost is an important barrier to the adoption of evidence-based practices and advocate for an approach in which intervention developers first assess what individuals and agencies are “willing to pay” for an intervention and then design interventions that are consistent with that cost range.

Two recent examples illustrate potential contributions of economic evaluation to implementation studies. Saldana and colleagues (2014) developed a tool for examining implementation activities and used it as a template for mapping implementation costs over and above the costs of the intervention; applying this tool to a foster care program, they found it valuable for comparing different implementation strategies. Holmes and colleagues (2014) describe the development of a unit costing estimation system (cost calculator) based on a conceptual model of core child welfare processes, and discuss how this tool can be used to determine optimal implementation approaches under different circumstances, as well as to estimate costs under hypothetical implementation scenarios.

These points were reinforced by a number of panelists who spoke at the committee’s open sessions about their work in implementing evidence-based

interventions at the federal, state, and local levels. Speakers noted that effective implementation depends on a number of factors, including data and monitoring systems, the workforce and its training, and resources that affect everything from provider compensation to the number of children or families seen by each provider. While knowledge of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions is growing, there remains only limited information about what is required to support effective implementation of those interventions.

At the committee’s June open session, panelist Mark Lipsey, director of the Peabody Research Institute at Vanderbilt University, commented that most cost-effectiveness research focuses on brand-name programs. However, the cost and infrastructure associated with implementing those programs are not feasible in most real-world settings. Communities generally lack the capacity and resources to implement the brand-name, model programs. Therefore, generic versions of the programs are implemented. Whether the effects suggested in research on brand-name programs can be expected in other settings is dependent upon the local resources available to implement the program, a large number of factors specific to the context where the program is implemented, and the quality of the implementation monitoring system. Lipsey suggested an alternative model to the traditional feed-forward approach in which highly controlled research on programs is conducted; synthesized, and placed in a clearinghouse, and efforts are then undertaken to implement those programs and replicate the findings in local settings. The context—population served, staff skills, resources, community, nature of the original problem—may differ from those of the programs in the original studies. Consequently, the results expected may not be realized in new settings. Alternatively, Lipsey suggested beginning with the monitoring and feedback systems currently in place in a particular setting and building incrementally toward evidence-based practice.

Gottfredson and colleagues (2015) also emphasize the importance of describing intervention implementation, although their focus is on prevention programs in health care. They note that the original research of economists and policy analysts “often generates conclusive answers to questions about what works under what conditions” (p. 895), but they give less attention to describing the intervention in subsequent trials in other settings and examining causes for variations in outcomes and costs. An example of the importance of implementation fidelity is described in Box 4-2.

In short, attention to the infrastructure and contextual aspects of effective implementation is often inadequate. Clearinghouses and registries have provided a systematic mechanism for synthesizing evidence of the effectiveness of interventions. Legislation has required the use of some of those evidence- or research-based models (Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative, 2015) without necessarily addressing issues of fidelity or ensur-

BOX 4-2

The Importance of Implementation Fidelity: An Example

The experience of Washington State’s implementation of Functional Family Therapy (FFT) illustrates the importance of implementation fidelity. In its 1997 Community Juvenile Accountability Act, the Washington State legislature required juvenile courts to implement “research-based” programs. To fulfill that mandate, the Washington State Institute for Public Policy (WSIPP) (which is described later in this chapter in the section on examples of efforts to improve the use of evaluation evidence) conducted a thorough review of the evidence base, and from that review, the state’s Juvenile Rehabilitation Agency identified four model programs from which courts could choose. The evidence base for those programs was not specific to Washington State, so the legislature also required that WSIPP evaluate the models’ effectiveness in Washington in “real-world” conditions. In its first evaluation of FFT, WSIPP estimated a $2,500 return on investment. However, that evaluation found that FFT was effective—and thus the returns were realized—only when therapists implemented the model with fidelity. In fact, WSIPP found that recidivism rates could actually increase relative to business as usual if delivered by therapists not appropriately trained. Thus, WSIPP recommended that the state work with FFT Inc. to develop a mechanism for training and monitoring therapists to ensure effective implementation of the program (Barnoski, 2002).

ing that resources are being devoted to effective implementation. Yet few model interventions have been demonstrated at scale, and it is not clear that those model interventions will produce the same or comparable outcomes when introduced into other settings and contexts with different resources available for implementation. Moving evidence-based practice and policy toward outcomes requires thinking in a holistic way about the range of evidence that is needed, its availability, and how the evidence aligns with existing systems and funding.

CONCLUSION: Infrastructure for developing, accessing, analyzing, and disseminating research evidence often is lacking in public agencies and private organizations charged with developing and implementing interventions for children, youth, and families.

CONCLUSION: It is not sufficient to determine whether an investment is effective at achieving desired outcomes or provides a positive economic return. Absent investments in implementation in real-world settings, ongoing evaluation, and continuous quality improvement, the positive outcomes and economic returns expected may not be realized.

CONCLUSION: Conceptual frameworks developed in the field of implementation science may be relevant to improving the dissemination and use of economic evidence, but the implementation literature has not paid sufficient attention to the potential role of economic evidence in these models.

Reporting

“Research often uses language and terms that require a PhD in economics to recall what the report is saying.”

—Barry Anderson, deputy director, Office of the Executive Director, National Governors Association, at the committee’s open session on March 23, 2015.

“We have to figure out a way to communicate this information in ways that resonate with different perspectives, so benefit-cost means something to people other than those who are in the field. During the times when policy has changed, it is because we found ways of communicating the power of change to different communities. It has to mean something to people in different parts of the political dynamic that we work with.”

—Gary VanLandingham, director, Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative, at the committee’s open session on March 23, 2015.

“There has been increased attention to local data dashboards. This entails the presentation of relevant, timely information to the right people at the right time so they can use data for continuous quality improvement and decision making. What are needed are both a data system and organizational documents with embedded agreements and expectations for [leaders’ and management teams’] timely use of local data on an ongoing basis. The administrative piece is just as important as the IT piece.”

—Will Aldridge, implementation specialist and investigator, FPG Child Development Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, at the committee’s open session on June 1, 2015.

The reporting of evidence derived from economic evaluation influences whether the evidence is used in decision making (National Research Council, 2012; O’Reilly, 1982; Orton et al., 2011; Tseng, 2012; Williams and Bryan, 2007). Relevant, credible evidence is more likely to be used if reported in a clear and concise format with actionable recommendations (Bogenschneider et al., 2013; DuMont, 2015). Reporting formats designed to suit the information needs and characteristics of target audiences also may increase the use of economic evidence.

The distinct communities of producers and consumers of economic

evidence, discussed above in the section on relevance, influence how this evidence is typically reported. For example, economists tend to expect confidence limits, sensitivity analysis on key parameters such as discount rates, and other estimates of the range of a possible return. Sometimes they provide a range as their main finding. Legislators and top-level managers, however, like clear, crisp recommendations. Instead of estimates presented as ranges or by a table of estimates under different assumptions, they generally prefer a point estimate and a plain-English explanation without further numbers expressing the analysts’ confidence in the results (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014; National Research Council, 2012). Policy makers also tend to want results given up front, with methods being described later and easy to skip without compromising comprehension. These preferences stand in marked contrast to the expectations of academic journals.

Similarly, when multiple economic analyses using different parameter choices are available for a single program, a plethora of inconsistent numbers can destroy the credibility of the results with decision makers. Instead, comparisons with prior estimates can be presented in a way that makes it clear at the outset which estimate is best, with why that estimate is better than prior ones then being explained.

Systematic reviews of evaluations and clearinghouses can be used to help decision makers sort through evidence to determine its relevance and practical implications. Yet many of these resources currently do not incorporate economic evidence. The work of the Washington State Institute for Public Policy (see Box 4-2 and the section below on examples of efforts to improve the use of evaluation evidence) is one exception, providing independent systematic reviews of evidence that include economic evidence. The Tufts University Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry is another tool that makes economic evidence accessible to users. Clearinghouses can help consumers acquire and assess the full range of evidence in a given area, but they are not a panacea since most present only evidence of effectiveness and typically only for the fairly circumscribed brand-name, model programs discussed in the previous section.

CONCLUSION: Economic evidence is more likely to be used if it is reported in a form that is summarized and clear to target audiences and includes actionable recommendations.

CONCLUSION: Research summaries and publications often do not report contextual details that are relevant to whether positive impacts and economic returns should be expected in other settings.

OTHER FACTORS IN THE USE OF EVIDENCE

The results of economic evaluation are one type of evidence on which decision makers may rely. Even when economic evaluations are of high quality (see Chapter 3), relevant to the decision setting, and feasible to implement, other factors—including political climate, values, budgetary considerations, and data availability—may influence whether the evidence they produce is used.

Political Climate and Values

“A project that has some prospects for success is subsidizing long-acting, reversible contraception. We received a grant from a philanthropist to do this on a volunteer basis with low-income girls and women. The results were amazing. There was a 40 percent drop in unwanted pregnancies. You can translate how much that would have cost the Medicaid Program. Here, we had a program with extremely compelling evidence and the potential to be duplicated within our state, but also touching this program were all of the politics around contraception, so there is a bit of an uphill climb on this one.”

—Henry Sobanet and Erick Scheminske, director and deputy director, Governor’s Office of State Planning and Budgeting, Colorado, at the committee’s open session on March 23, 2015.

“Over half of our county’s budget is education costs. Education is a very important value in our county.”

—Uma Ahluwalia, director, Montgomery County, Maryland Department of Health and Human Services, at the committee’s open session on March 23, 2015.

“Data will never trump values by itself. But data that has a compelling [personal] story attached to it, and that also is linked to the ideology of the people we are trying to communicate with can trump an individual perspective.”

—Gary VanLandingham, director, Pew-MacArthur Results First Initiative, at the committee’s open session on March 23, 2015.

Economic evidence is but one of several factors that policy makers must weigh as they make decisions about choosing among competing priorities (Gordon, 2006). In a pluralistic society, diverse political views, cultural norms, and values help define the context within which individuals make investment decisions. Numerous external factors, such as stakeholder feedback, legal actions, and the media, affect the use of evidence in the policy-making process (Zardo and Collie, 2014). Existing political pressures and

cultural belief systems influence not only decisions at the individual level, but also organizational practices and structures that may facilitate or hinder the use of scientific evidence in decision making (Armstrong et al., 2014; Flitcroft et al., 2011; Jennings and Hall, 2011; National Research Council, 2012; Nutbeam and Boxall, 2008).

Those working to increase the use of economic evidence will be more successful if they remain cognizant of the political environment within which an agency or institution is working. What are the external pressures? Are important external audiences open to diverse information, or are they only looking for confirmation for previously held views? Short-term budgetary concerns also may trump information about long-term efficiency. In addition, long-standing programs with little evidence of success often have strong, vocal allies in the form of providers and beneficiaries who exert pressure on agency leaders or local politicians who make resource allocation decisions.

Armstrong and colleagues (2014) state that “decision making is inherently political and even where research evidence is available, it needs to be tempered with a range of other sources of evidence including community views, financial constraints and policy priorities” (p. 14). In a study of the use of research by school boards, researchers found that school boards typically relied on a variety of information sources, including examples, experience, testimony, and local data (Asen et al., 2011, 2012). Research (defined as empirical findings, guided by a rigorous framework) was used infrequently compared with other types of evidence (Asen et al., 2013; Tseng, 2012). When research evidence was relied upon, it was cited in general rather than with reference to specific studies, and most commonly was used as a persuasive tool to support an existing position.

Studies of the use of economic evidence in local decision making across countries have found that political, cultural, and other contextual factors influence the application of such evidence, especially if it is found to contradict prevailing values or local priorities (Eddama and Coast, 2008). A European study found that the extent of knowledge about economic evaluation, the barriers to its use, the weight given to ethical considerations, and incentives promoting the integration of economic information into health care decision making varied by country. The authors suggest that if economic evidence is to have a stronger influence on policy making, the political and institutional settings within which decisions are made will require greater attention (Corbacho and Pinto-Prades, 2012; Hoffman and Von Der Schulenburg, 2000).

One area of contrast between the United States and some European countries is in the use of economic evidence in decisions on health policy (Eddama and Coast, 2008): the latter countries are more likely to rely on cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) to shape their health policies (Neumann,

2004). In fact, language in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) explicitly prohibits the application of CEA in the use of Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) funds that support the piloting of health care innovations (Neumann and Weinstein, 2010).

The use of economic evidence in policy making varies across U.S. policy-making enterprises. A number of federal agencies use benefit-cost analysis (BCA) or budgetary impact analysis to inform the legislative process (e.g., the Congressional Budget Office [CBO]) and in the approval of regulatory actions (e.g., the Office of Management and Budget [OMB]). In some fields methodological and ethical questions about the use of BCA—for example, to monetize certain outcomes, such as human life—can diminish the uptake of economic evidence (Bergin, 2013). The use of CEA to justify funding of preventive interventions but not treatment services under Medicare highlights the inconsistent and uneven use of economic evidence in policy making seen in the United States (Chambers et al., 2015).

Producers of economic evidence can consider contextual and organizational variables in their study design, analysis, and interpretation of findings so that research results better address the core issues decision makers face. Economic evaluations then are more likely to be seen as responsive, sensitive, and relevant to the local context and to increase the demand for and uptake of such work.

CONCLUSION: Political pressures, values, long-standing practices, expert opinions, and local experience all influence whether decision makers use economic evidence.

Budgetary Considerations

A budget process that takes into account only near-term costs and benefits—such as the 10-year window within which federal budget decisions are made, or the budget decisions of a foundation wishing to prove near-term success even with the use of economic evidence—will inherently entail a bias against investments in children, whose returns are long-term in nature. This observation creates an additional impetus for statistical entities such as the Census Bureau and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Statistics of Income program, as well as surveys supported by private foundations, to give significant budget weight to the development of longitudinal data on children.

Economic evaluation also tends to focus on the intervention, local community, or organization, comparing internal costs with internal benefits. Budget offices can mitigate the tendency to localize decision making by both providing information on gains (or costs) accruing outside of a local constituency or jurisdiction and suggesting policy options for maximiz-

ing all societal benefits in excess of costs. For instance, a federal program providing health care to children through states can account for net gains or losses nationwide, while budget analyses can inform policy makers of ways to design laws so as to avoid giving states incentives to discount gains outside their jurisdictions.

In formulating budgets, governments and private organizations ultimately decide how they will allocate their resources. Ideally, budget processes force governmental and private entities to make trade-offs at the broadest level, allocating monies to those interventions with the greatest benefits relative to costs. Under these ideal conditions, economic evaluations would be extensive and encourage decision making broadly across interventions while promoting negotiations among interventions, with multisector payoffs in mind. As has been made clear throughout this report, however, economic evaluations often are quite limited in both number and content. The total costs of an intervention frequently are excluded from the evaluations that are performed. Yet decisions will be made. The budget will be fully allocated one way or the other, even if the saving is deferred to another day or, in the case of government, returned to taxpayers. Bluntly, while one intervention’s expansion may await further economic evaluation, the budget will, regardless, fully allocate 100 percent of funds.

In practice, in many if not most cases, government budgetary decisions and the delivery of services take place within silos. Different departments and legislative committees separately oversee education, food, housing, and health programs for children without fully taking into account the impact in other program areas. Similar silos often characterize foundations and other private organizations engaged in making investment decisions for children.

In the practical world of budgets, therefore, the ideal is never fully met, often because of limitations of time and resources. Even with the best of economic evidence available, the evidence is never fully informative at every margin of how the next dollar should be spent (or returned to taxpayers). Given these limitations, there are nonetheless three dimensions in which budget processes could be improved to take better advantage of the evidence derived from economic evaluations: (1) reporting on the availability and absence of economic evidence; (2) allocating budgetary resources to take fuller account of the time dimension that economic evaluation needs to encompass, particularly for children, whose outcomes often extend well into adulthood; and (3) accounting for net benefits and gains beyond any particular intervention, constituency, or organization.

Reporting on the Availability and Absence of Economic Evidence

While Chapter 3 emphasizes the gains possible from the production of high-quality economic evidence, the focus here is on what budget offices

can do with the evidence that is and is not available. To the extent possible, decision makers need to be as informed as possible in their decision making. Thus they need to know what economic evaluations are available, not available, planned, and not planned for programs falling within their budget.

For example, OMB could list annually which programs do and do not have economic evaluations planned as part of their ongoing assessment, where the evaluations exist, and what has been evaluated. Such programs could include those implemented through tax subsidies or regulation, not just direct spending, as in the case of earned income tax credits, which accrue largely to households with children. Similarly, CBO regularly reports on options for reducing the federal budget deficit. In so doing, it could both report on the extent to which these options make use of economic evidence and recommend use of the availability of economic evidence as one criterion for decision making.

Allocation of Budgetary Resources to Account for Outcomes over Time

Returns on investments take place over time. No one would invest in a corporate stock based solely on the expected earnings of that corporation over 5 or even 10 years; the company’s net value depends on its earnings over time. Similarly the returns on interventions for children often accrue over a lifetime, and, as indicated in Chapter 3, often take the form of longer-term noncognitive gains such as decreased dropout rates, lower unemployment upon leaving high school, or lower rates of teen pregnancy.

Unfortunately, it is often easier to negotiate support for interventions with near-term gains since those gains may be both more visible and more likely to accrue to the benefit of public and private officials running for office or being promoted on the basis of their near-term successes. Likewise, a school board may more easily gain support for an intervention aimed at children ages 3 to 5 if it will improve performance in second grade 3 years later than if it will improve graduation rates 14 years later. Even CBO reports on the budgetary effects of proposed changes in the law cover only 10 years, with some exceptions for programs such as Social Security.

Since this is not a report on budget process reform, only two basic points are important to make here. First, decision making will be improved when decision makers are fully informed of these limitations. This is a particular issue when, as noted, program allocations are being made with and without economic evidence at hand. Particularly when it comes to investments in children, a short-term horizon biases those budgetary decisions in favor of interventions with short- but not long-term benefits, such as higher consumption levels for beneficiaries within a budget window and returns to existing voters but not those younger or not yet born. Economic evaluations that similarly focus on the short term add to those budgetary biases.

Second, if returns on investments in children are long term, data are needed to follow those children over extended periods of time. Relatedly, the linkage of long-term data across systems and sectors is an important step toward improving their use. Although there are challenges to the systematic linkage of data (e.g., the outdated design of administrative structures and systems, data privacy, tracking of children and families),1 there is still significant potential in these efforts (Brown et al., 2015; Chetty et al., 2015; Cohodes et al., 2014; Lens, 2015). Establishing personal relationships between the collectors and users of the data, shadowing successful project designs (e.g., the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods,2 the Three City Study3), or seeking guidance from other fields (e.g., criminal justice) could provide opportunities for continuing to address these challenges.4 (See Chapter 5 for additional discussion of data linkage.)

On the other hand, one could depend on developing new and expensive data sets with each new experiment or program adoption or extension. But that approach likely would be cumbersome and expensive, even if worthwhile. Statistical entities, such as the Census Bureau and the IRS’s Statistics of Income Program or those associated with state K-12 and early childhood education, could gain more from their limited budgets if they gave significant budget weight to the development of longitudinal data following individuals. Foundations interested in economic evaluation could also assess the relative importance of a new experiment requiring new data development and more investment in data that could inform multiple investments. Students and youth provide an ideal case in point. Educational and early childhood reform efforts consistently try new experiments, many of which are amenable to economic evaluation. Well-developed data following young children and students over extended periods of time could allow multiple evaluations to make use of a common set of data, such as progress along various outcome scales, even if the separate evaluations still required additional input of data, say, on cost differences related to different experimental designs.

___________________

1 Observation made at the committee’s open session on June 1, 2015, Panel 2; see Appendix A.

2 For more information on this effort, see http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/PHDCN/about.jsp# [June 2016].

3 For more information on this effort, see http://web.jhu.edu/threecitystudy [June 2016].

4 Observation made at the committee’s open session on June 1, 2015, Panel 2; see Appendix A.

Accounting for Net Benefits and Costs Across Interventions, Constituencies, and Organizations

Compartments, silos, and limited frameworks constantly affect budget decision making, and as a result, the economic savings from investing in effective strategies may not accrue to the intervention, constituency, or government entity making the investment. For instance, a community may invest in early childhood education, but given the mobility of families, the gains from that investment often will accrue to jurisdictions to which those families move. In technical BCA terms, when internal costs are compared with internal benefits, external costs and benefits are ignored. One study, for instance, found that the societal return needed to realize government savings on drug and crime prevention interventions varies widely among sectors, and even for government saving alone, depends on whether the calculation is made at the federal level or at the federal, state, and local levels combined (Miller and Hendrie, 2012).

How can budget offices make a difference here? For one, budget decisions frequently are made at high levels at which gains across boundaries can be combined. For instance, OMB often guides final budget decisions for the President when reviewing particular agency requests. Even a particular agency, as long as its goal is the well-being of constituents, can mitigate its own tendency to localize decision making by reporting economic evaluations across program areas, even those not under their jurisdiction.

Budget offices also can identify for policy makers and administrators incentives that might offset built-in tendencies to account only for local costs and benefits. For example, many federal programs in areas affecting children are implemented on the ground through state and local officials, and many state programs are implemented through local officials, thus resulting in transfers of benefits and costs across jurisdictions. Additional features can be added to programs so that offsetting transfers are made to compensate jurisdictions bearing costs for benefits they do not receive. Economic evaluations can account for gains and losses across all jurisdictions.

OMB, for example could list which programs do and do not have economic evaluations planned as part of their ongoing assessment. Such programs could include those implemented through tax subsidies or regulation, not just direct spending. In addition, in its annual review of options for reducing the deficit, CBO could recommend using the availability of economic evaluation as one criterion for decision making.

CONCLUSION: Budgets allocate resources one way or the other. Those decisions will be made regardless of whether the results of economic evaluation and other forms of evidence are at hand or the

research is planned for the future. It is desirable to have access to as much information as reasonably possible. Economic evaluation can be influential in a world where decision making is made with incomplete information.

CONCLUSION: Budget choices often factor in only near-term cost avoidance and savings and, even when evidence from benefit-cost analysis is available, near-term benefits. Benefits from investments in children, youth, and families, however, often are measured most accurately over extended periods continuing into adulthood.

CONCLUSION: The economic savings that result from investing in effective strategies may accrue to constituencies or government entities other than those making the investments.

Data Availability

“There aren’t archives out there where researchers or administrators or anybody else can go to get linked administrative data at the local, state, or federal level to do what we need to do. It’s the access issue that is the concern here.”

—Robert M. George, senior research fellow, Chapin Hall at University of Chicago, at the committee’s open session of June 1, 2015.

“At times it can be difficult to get the federal government to share data across different agencies. It can be even harder to get state agencies to share data across its agencies or with the federal government.”

—Beth A. Virnig, director, Research Data Assistance Center, University of Minnesota, at the committee’s open session of June 1, 2015.

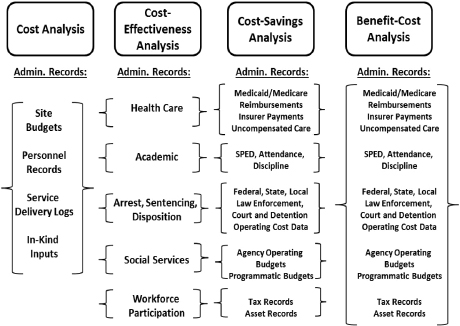

Opportunities exist to use administrative data to help meet the data needs of different types of economic evaluation.5 In particular, cost analysis (CA), CEA, cost-savings analysis, and BCA produce distinct types of evidence that can be used to answer different questions. They also use different types of administrative data and leverage those data in different ways. Figure 4-1 depicts the potential uses of administrative data in economic evaluations.

CA benefits from accessing administrative data that are qualitatively

___________________

5 Big data, innovative data-sharing technologies, and the emerging field of data science are relevant to the discussion of the use of economic evidence; within this report, however, these topics are not explored in depth.

NOTE: SPED = special education.

SOURCE: Adapted from Crowley (2015).

different from those used for other types of economic evaluation. Particularly key is the use of site budgets, personnel records, and service delivery logs. Site budgets, often one of the main sources of administrative data used for CAs, help establish the quantity of resources used and provide the actual prices paid to operate an intervention. Personnel records are used to determine what labor resources were used for what intervention activities. And service delivery logs are used to determine the size of the population served. Programs that use coordinated data systems to track service delivery at the individual level produce administrative records that allow for individual cost estimates by apportioning total costs to specific individuals. This process can provide more precise estimates than average cost estimates with poorly understood variability. Finally, reports on in-kind contributions that may supplement parental grants or contracts also can be mined to estimate the total costs for an intervention. Ignoring such supplemental resources can result in underestimating the cost of infrastructure and jeopardize future replication of an intervention.

CEA uses many of the same records considered in an effectiveness analysis. Record domains including health care, education, criminal justice,

social services, and workplace participation all are relevant. In a CEA, impacts captured by outcomes on administrative records can be considered in the context of an intervention’s cost. Whether the intervention is considered cost-effective depends on the payer’s willingness to pay for the achieved change in outcomes.

Cost savings analysis makes it possible to consider an intervention’s impact and efficiency in more absolute terms. Cost savings analyses can leverage administrative data similar to those used in CEA, but often look to data that are linked to budgetary outlays. In health care these data include Medicaid and Medicare reimbursements, private insurer payments to providers, and uncompensated care costs at both the provider and government levels. In education, the focus is often on cost drivers such as special education and disciplinary costs, as well as areas linked to public spending, such as attendance. Criminal justice records for individuals often are combined with administrative data on law enforcement spending, as well as court and detention operating costs. Specifically, when criminal records indicate the quantity of criminal justice resources spent on individuals, data on local, state, and federal spending can be used to estimate the price of those resources. In a similar fashion, individual-level social services data can be used in combination with social services agency and programmatic budgets to estimate quantity of resources consumed and the local prices for providing them. Importantly, within the social services domain, programmatic budgets alone are not sufficient for estimating prices. The infrastructure costs of the service providers also must be included in the price estimates, and often can be derived only from agency operating budgets. Lastly, evaluations of workforce participation in cost savings analyses generally focus on impacts on wealth, income, and tax revenue, requiring access to tax and asset records.

While a cost-savings analysis generally would consider only one of these domains at a time, a full BCA would leverage these records to assess impact across systems and arrive at a full net benefit of the intervention that accounted for savings in one system and increased costs in another. Outcome evaluation of interventions for children, youth, and families ideally requires longitudinal data on changes in disparate aspects of well-being: education, health, safety, housing, employment, happiness, and so on.

While administrative data sets contain much of the information needed for CA, CEA, cost-savings analysis, and BCA, these data may not be available. Administrative data often are not stored centrally. Local data systems tend to use varied formats, archive differing information, use incompatible file formats, and sometimes overwriting data instead of archiving them. Some systems are not even automated. Even if data are centralized, local cost recovery objectives may preclude retrieving them from the central

source. Centralized data also tend to be a snapshot in time and place, while local data may be updated.

Even automated data often are not readily accessible. Privacy rules differ between health care and education data, but they often preclude access to identifiable records. Even signed consent will not enable access to identifiable tax records or Social Security earnings records.

The problem becomes especially acute when data cut across silos. The department funding a trial usually will try to contribute the data it owns to an evaluation, but may lack the leverage to convince other departments to spend resources on providing data or breaking barriers to support an evaluation.

The private sector now has data that dwarf the amount of public data. Every credit card swipe goes into a commercial database that documents buying habits and often also into a vendor database with details of who purchased what, where, and when. Sensors in crash-involved vehicles provide driving and impact data in millisecond intervals. And medical records increasingly are electronic. Thus, the data needed to answer many policy questions are housed in private data systems. Increasingly, the same is true of data needed to answer questions about the long-term outcomes of randomized controlled trials. The pressing question is how those data can be accessed affordably and ethically.

Access to data from randomized controlled trials also may be limited in ways that hamper maximizing the lessons learned from the trials. Trial managers are protective of their data. They fear confidentiality could be breached. They lack the resources to document and share deidentified data and answer questions about the data posed by prospective users. And they worry that their data could be misanalyzed. Yet meta-analyses are more powerful and accurate if unit record data can be pooled. It is unclear where the proper balance lies here.

CONCLUSION: Federal agencies maintain large data sets, both government-collected and resulting from evaluations, that are not readily accessible. Privacy issues and silos compound the challenges of making these data available. Improving access to administrative data and evaluation results could provide opportunities to track people and outcomes over time and at low cost.

CONCLUSION: Without a commitment by government to the development of linkages across administrative data sets on education, health, crime, and other domains, both longitudinally and across systems, efforts to expand the evidence base on intervention impacts and evidence of economic returns will be limited.

FACTORS THAT CAN FACILITATE THE USE OF ECONOMIC EVIDENCE

Factors related both to organizational culture and management practices and to collaborative relationships can facilitate the use of economic evidence.

Organizational Culture and Management Practices

Organizational culture and management practices, including leadership, openness to learning, accountability, performance management, and learning forums, can promote more optimal use of economic evaluation. The focus in this section is on the dynamics within decision-making bodies. Some of the factors that provide an impetus for an organization to conduct economic evaluation are briefly reviewed in Box 4-3.

Leadership and Openness to Learning

Some organizations have a culture or characteristics that are supportive of the use of evidence, including the results of economic evaluation, such as leaders and managers who value economic evaluations and have sufficient

BOX 4-3

The Impetus for Economic Evaluation: Examples

Proposals internal to an organization, as well as legislation with a direct impact on the organization’s budget, will frequently generate cost analysis (CA). The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), for example, requires CA for passage of federal legislation with a budget impact. Because CAs provide important information about the economic impacts of legislation, they may be accompanied by cost-effectiveness analysis (although CBO is likely to include such information in separate, program-related studies). As a routine matter, however, legislation often is not accompanied by information relating costs to the effectiveness of particular interventions (benefit-cost analysis) or assessing an intervention’s cost-effectiveness relative to other options with the same goal.

As another example, the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs administers Executive Order 12866 58 FR 51735, which requires federal agencies considering alternatives to rulemakings to provide an analysis of the costs and benefits of these alternatives. In theory this requirement has led to improved decision making, although there is not a strong evidence base indicating that it has in fact resulted in more cost-effective rules (Harrington and Morgenstern, 2004).

knowledge to understand and make use of them. Such characteristics have been known to influence the extent to which economic evaluation is used to make programmatic or budgetary decisions (Armstrong et al., 2014; Brownson et al., 2009; Jennings and Hall, 2011). Researchers, both internal and external, can promote the use of economic evaluation when they understand the organization, develop relationships with leaders and other potential users who become involved in joint decision making involving the evidence (Nutley et al., 2007; Palinkas et al., 2015; Williams and Bryan, 2007), and communicate results in ways that increase understanding and use of the evidence (National Research Council, 2012; Tseng, 2012).

Organizations open to discussion and learning are more receptive to the use of evidence, including rigorous economic evaluations, that may run counter to their experiences and beliefs (Cousins and Bourgeois, 2014). Changes in the organizational culture may therefore be required to make an organization receptive to the use of economic evidence. Such changes may entail not only leadership and support from the top of the organization, but also external support and access to the resources needed to achieve a shared vision for the acquisition and use of such evidence (Blau et al., 2015; Hoyle et al., 2008). Changes also may entail attention to future needs, including the data required for economic evaluation. (See the section above on budget considerations for discussion of budgeting for the development of data in advance of future economic evaluations.) Further discussion of the importance of a culture of learning is included in the section below on performance management.

Wholey and Newcomer (1997) argue that organizations and their cultures should be examined before a study is undertaken to determine whether the organization is, in fact, prepared to use the evidence produced by the study. Funders, both public and private, who want to promote the use of economic evidence might choose to place their resources in organizations that are more receptive to doing so—thereby also providing incentives for other organizations to perform more economic evaluation.

CONCLUSION: Economic evidence is more likely to be used if it has leadership support and if the organizational culture promotes learning.

Accountability

Accountability involves delegation of a task or responsibility to a person or organization, monitoring the delegate to observe performance, and delivering consequences based on that performance. It arises in such relationships as supervisors’ evaluation of employees’ performance, auditors’ concerns with fiscal accountability, shareholders’ interests in company performance, and funders’ concerns with the success of the projects they fund.

Accountability is a central tenet of representative democracy (Greiling and Spraul, 2010), as citizens want to know how well the government to which they have delegated power has performed, and then deliver consequences through elections or other feedback channels.

Veselý (2013) notes that “accountability” is one of the most frequently used terms in public administration, but has many different meanings. He identifies four current usages, including “good governance” and a means to ensure the quality and effectiveness of government. Lindberg (2013) found more than 100 different subtypes and usages of accountability in the scholarly literature; he sees the major subtypes as political, financial, legal, and bureaucratic.

As the accountability movement has continued, its drawbacks, or unintended side effects, have become more obvious. These efforts can take time and resources away from an organization’s primary goals; that is, accountability, too, involves a cost that must be related to benefits. Sometimes standards are unrealistic, or criteria for judging are contradictory. Agencies may focus on success of the tasks being measured or on one type of benefit, and neglect other goals or the broader picture. Accountability typically involves a top-down approach, whereas economic evaluation should be considered valuable in strengthening, not just threatening, decision makers. Those promoting the use of economic evidence would do well to understand why greater accountability can but not necessarily does promote the use of economic evidence or better performance (Halachmi, 2002; Veselý, 2013). The example in Box 4-4 illustrates the potential negative effects of an emphasis on accountability.

One bottom line is that economic evaluation first and foremost provides valuable information for constructive problem solving. If people think that results of evaluations and other data will be used against them (e.g., for budget cuts or other unfavorable consequences), they will react accordingly (Asen et al., 2013; Lorenc et al., 2014). They may aim to improve the specific outcomes being measured without actually improving anything—for instance, by serving only those who are most likely to achieve some outcome or by manipulating the data (Brooks and Wills, 2015).

Nevertheless, the interest in accountability will continue, and rightly so. The theory is somewhat incontrovertible: if people are accountable for their actions, they usually will respond to the incentives involved. It is in the application of accountability schemes that difficulties arise. There is a learning agenda implied by the above-described mixed experience with accountability frameworks. As Coule (2015) puts it, there is increasing recognition that the notion of accountability as “a somewhat benign and straightforward governance function” is, instead, “a challenging, complex choice” (p. 76).

BOX 4-4

Illustrative Example of Accountability: No Child Left Behind

An example of the ways in which strong accountability systems can overtake the gains available from a good information and economic evaluation system and even result in unintended consequences is the K-12 accountability provisions contained in the federal No Child Left Behind Act.* The act’s goal of academic proficiency for all students as measured by state standardized tests of math and English language arts has resulted in a system highly focused on improving test scores. As a result, untested subjects, such as foreign languages or social studies, may be given short shrift. Students well below or well above proficiency have received less attention than others since they are less likely to contribute to a school’s overall measures of progress. The National Research Council’s (2011) report suggests that test-based incentive systems have had little effect on student achievement and that high school exit exams “as currently implemented in the United States, decrease the rate of high school graduation without increasing achievement” (pp. 4-5).

At the same time, by promoting the use of measures of progress, No Child Left Behind holds considerable promise for leading to many types of economic evaluation of different approaches to teaching, learning, and use of school resources. A more modest and attainable accountability system might first emphasize obtaining better measures of individual student progress that are useful to teachers and principals (e.g., as early warning signals of a student’s no longer making progress), as well as for performing multiple levels of experimentation amenable to future economic evaluation.

*In December 2015, the No Child Left Behind Act was replaced by the Every Student Succeeds Act (Public Law No:114-95).

Performance Management

Closely related to accountability systems are performance management and monitoring. The theory or logic model entails monitoring performance to achieve greater accountability and then better performance. Government-wide reforms, such as the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) of 1993, the George H.W. Bush-era Program Assessment Rating Tool (PART), and the current GPRA Modernization Act of 2010 are prime examples of the creation of performance management systems aimed at making data more widely used in decision making. Policy-specific changes in such areas as safety-net programs (the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996) and education (the No Child Left Behind Act of 2002 and the Race to the Top initiative of 2009) provide further incentive for the use of performance measures within specific policy areas.

Economic evaluation can and has played an important role in performance management.

An area ripe for further research is the role of continuous improvement or continuous quality improvement both in supporting the implementation of evidence-based practices and in ensuring that the implementation of those practices is helping to improve outcomes. As part of the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program, for example, states are required to submit an implementation plan to the federal government. Among the items they must include is a plan for using data for continuous quality improvement. This requirement suggests that it is important not only to use data and evidence to identify which types of programs or practices can produce outcomes or savings that offset their costs, but also to have a system to continually monitor the implementation of these efforts and ensuring that implementation and outcomes are both moving in the expected direction. As noted earlier in this report, the implementation of interventions can strongly influence whether they produce the expected outcomes. Other factors—including community-level factors, historical context, and the choice of a counterfactual—also can affect outcomes. Thus, it is important in promoting evidence-based practice to identify ways in which governments and providers can monitor their programs continuously to ensure that they are producing the desired benefits.

Moynihan (2008) argues that performance data (of which economic evaluation is one type) is not comprehensive. For any complex program or task, there are multiple ways of capturing performance, and performance data could not reasonably be expected to replace politics or to erase information asymmetries in the policy process. This does not mean that these data are not useful if applied in a realistic system of improvement, rather than one focused on some final determination of merit. Moynihan also points out that performance data are more likely to be used purposefully in homogenous settings, where individuals can agree on the basic goal of a program.

Techniques such as BCA certainly have an appeal in being less susceptible to subjectivity than the selection of a simple performance target. But even as the importance and sophistication of BCA have risen, the political process should not be expected to cede decision making to even the best technical analysis. Organizational learning remains the central management benefit of performance data, including economic evidence, for complex tasks. Learning requires a willingness to observe and correct error, which depends in turn on frank discussions about what is working and what is not, as well as the limitations of even the highest-quality analysis.

Learning Forums

A classic error governments have made in efforts to link data to decisions is to pay inadequate attention to creating routines for the use of data. Learning forums are structured routines that encourage actors to closely examine information, consider its significance, and decide how it will affect future action. The meaning of data is not always straightforward; even the answer to such basic questions as whether performance is good or bad may be unclear. Learning forums provide a realm where performance data are interpreted and given shared meaning. More complex questions, such as “What is performance at this level?” or “What should we do next?” cannot be answered simply by looking at the data, but require deeper insight and other types of knowledge that can be incorporated into learning forums (Moynihan, 2015).

Such routines are more successful when they include ground rules to structure dialogue, employ a nonconfrontational approach to avoid defensive reactions, feature collegiality and equality among participants, and include a diverse set of organizational actors responsible for producing the outcomes under review (Moynihan, 2008). Moynihan and Kroll (2015) note that although no learning forum will be perfect, following principles and routines—for example, focusing on important goals and on some of the factors discussed in this and the previous chapter, such as committed leadership, timely information, a staff well trained in analyzing data, and high-quality data—can make a forum successful. A learning forum also will be more effective if it incorporates different types of relevant information. Quantitative data are more useful when they can be interpreted by individuals with experiential knowledge of process and work conditions that explain successes, failures, and the possibility of innovation (Moynihan, 2008). The latter type of information also might be derived from some type of evaluation, ideally with treatments and controls, a BCA, or a CEA.

A Potential Role for Funders

How might the broad conclusions on organizational culture and a continuous learning process presented in this section influence public and private funders? In sponsoring economic evaluation, funders often explicitly or implicitly seek or rely on a theory of causality: How do particular activities in this particular analysis result in specific outcomes? That question can beg how the evaluation and the theory itself should adapt in a process of newer learning and continuous improvement. Funders might consider granting funds to support the use of monitoring systems and feedback loops, thereby enabling nonprofits or government agencies to use economic and other data

and evidence to learn, adapt, and incorporate new understandings into an ongoing cycle of improvement.

CONCLUSION: Economic evidence is most useful when it is one component of a continuous learning and improvement process.

Collaborative Relationships

“There is a process involved to get individuals who are not naturally researchers to think about how they should use this type of information. It is building relationships. It is building trust. It is not a one shot thing.”

—Dan Rosenbaum, senior economist, Economic Policy Division, Office of Management and Budget, at the committee’s open session on March 23, 2015.

Studies relating to the use of economic evidence in policy making suggest that the “disjuncture between researchers and decision-makers in terms of objective functions, institutional contexts, and professional value systems” (Williams and Bryan, 2007, p. 141) requires considering an interactive model of research utilization that would increase the acceptability of economic evidence (Nutley et al., 2007). Tseng (2012) argues that improving the quality of research itself is insufficient, noting that “relationships are emerging as key conduits for research, interpretation, and use. Policymakers and practitioners rely on trusted peers and intermediaries. Rather than pursuing broad-based dissemination efforts, there may be value in understanding the existing social system and capitalizing on it” (p. 13).

A systematic review of 145 articles on the use of evidence in policy making in 59 different countries found that the factor that most facilitated use was collaboration between researchers and policy makers, identified for two-thirds of the studies in which use was achieved (Oliver et al., 2014a). Other facilitating factors included frequent contact; relevant, reliable, and clear reports of findings; and access to high-quality, relevant research.